|

By Alexander Macdonald, Sab-Editor, North British

Agriculturist, Edinburgh.

[Premium—Twenty-Five Sovereigns.]

Introduction.

The small industrial county of Renfrew has a

circumference of some 80 miles. With an area of about 254 square miles,

it stands twenty-seventh among the thirty-three Scotch counties, and in

order of valuation it ranks sixth. Its total acreage is 162,428, of

which 2021 acres are foreshores, and 3621 acres covered by water; while

it has a gross valuation of £676,101, inclusive of railways and other

public undertakings. Of the land area nearly two-thirds are under

cultivation, the remainder being hill grazings, waste grounds, or

occupied by buildings and lying between 55° 40' 40" and 55° 58' 10" N.

lat., and 40° 13' and 4° 52' 30" W. long., the county assumes an

irregular oblong form, the axis of which runs parallel to the river

Clyde. It skirts Lanarkshire on the east and north-east, Ayrshire on the

south, and it is separated from Dumbartonshire on the north and

Argyllshire on the west by the Firth of Clyde.

It embraces sixteen parishes—which we shall have

occasion to name afterwards—inclusive of small portions of Beith and

Dunlop parishes attaching on the south side, and Govan on the

north-east. Though somewhat uneven, its surface is less rugged than that

of the neighbouring counties. There are no hills of sufficient height to

rank as mountains. The southern and western districts, however, are

interspersed with lochs and mosses, and dotted with hills

of various heights. Four peaks in the parish of Eaglesham average

well-nigh 1000 feet, but the loftiest summits are Mistylaw and Hydall,

in the parishes of Lochwinnoch and Kilmalcolm, the former rising to 1663

feet and the latter to 1244 feet above sea-level. Irrespective of

height, the most clearly defined ranges are those of Fereneze and

Gleniffer, which extend from Levern Valley, in Neilston, through the

Abbey parish to the western border of Lochwinnoch. This formation

renders the climate generally moist, though by no means severe. To the

scenery, too, it lends variety, and the county is thus possessed of

something more than objects of mere historical interest. It participates

in the finest of Scottish scenery, and from several of the hills,

notably those in Inverkip and in the neighbourhood of Greenock,

magnificent views are obtained.

Like most maritime counties, Renfrewshire might be

classified in two divisions—low-lying and upland—but agriculturally it

resolves itself more strikingly into three districts; that is to say,

its agricultural resources can best be described as we find them

regulated by the elevation, character, and quality of the land. The

three divisions—hilly, gentle-rising, and the flat— differ materially

not only in character of surface and soil, but also in the modes of

farming adopted. The hilly district is chiefly bleak moorland, the

gentle-rising division embraces many well cultivated as well as good

pastoral farms and finely-wooded heights, while the flat district, known

locally as the "Laich Lands," has for many years produced magnificent

crops of grain, fodder, and roots.

As may be inferred from the fact that as late as 1872

there were no fewer than 3215 proprietors, the land is still pretty

largely divided. In that year 148,679 acres, valued at £396,655, 16s.,

were owned by 657 proprietors of 1 acre and upwards, while 2558 owners

of less than 1 acre shared among them 1242 acres, having a united value

of £165,155, 7s. This estimate was substantially corroborated by a

statistical return in 1879, which shows that 155,321 acres, with a total

gross rental of £990,898, were divided among 5735 proprietors. One owner

held 24,951 acres, with a rental of £14,801; two together owned 27,775

acres, yielding a united rental of £27,059; one 6500 acres valued at

£5562; thirteen possessed 44,625 acres, of which the total rental was

£65,977; eight shared 12,128 acres, and a rental of £28,963; seven held

4793 acres, worth £17,972; and ninety derived £174,018 from their united

possessions of 19,651 acres.

Historically, Renfrewshire is peculiarly interesting.

It has given to Scotland some of her most valiant defenders, including

the heroic Wallace, and stands prominent in history as one of the

ancient residences of the Stewarts. In 1164 it was the scene of a

desperate battle occasioned by the rebellion of Somerled—the Lord of the

Isles—against King David I. The engagement took place near the Knock,

when the brawny men of Strathgryffe (the ancient name for Renfrew),

under the command of High Steward Walter, are said to have routed the

troops of Somerled and killed their leader. A similar affray occurred in

the reign of Alexander III., when Haco, king of Norway, who landed near

Largs with an army, suffered a crushing defeat. Nor, unfortunately, was

this all. Victory was not always assured. The men of Renfrewshire, who

tools part in the defence of Queen Mary, were repelled by the invading

troops of Regent Murray at Langside in 1568. And this was followed by a

similar rebuff in 1685. In that year a protracted struggle occurred near

Inchinnan Bridge between the troops of King James

VII. and some 1500 discontented Scots from abroad, led by the

Marquis of Argyll. The Marquis was captured, brought to Edinburgh, and

executed; but this did not prevent his little army from accomplishing

their purpose. They entrenched themselves in the neighbourhood of Hill

Port, and with marvellous valour and persistent fight ultimately

succeeded in annihilating the king's troops. This result may be said to

have ended the troublesome times of the inhabitants of the county, and

they have since then, or rather since the Union, to which they were

reluctant in acceding, devoted themselves to peaceful arts and

manufactures. They have established one of the most extensive

shipbuilding trades in the empire, and their ships plough the waves of

every sea. In other industries, too, they occupy a first place. Their

manufactures are prized at home and abroad, and have made for themselves

a name in the "far-off islands of the sea."

Renfrewshire is studded with towns and populous

hamlets, the former numbering twelve and the latter about thirty. The

only royal burgh is Renfrew, which, together with Port-Glasgow, returns

a member to Parliament. Paisley and Greenock have each a representative

in Parliament, while the county returns two members to St Stephen's. One

of the most striking features of the county is the large number of

mansions which adorn its sylvan slopes and vales, and the thriving

appearance imparted to it by the innumerable handsome residences

recently erected by Glasgow gentlemen.

There is no lack of facilities of transport. The

county is well supplied with roads, railways, and navigable waters. It

is intersected by several main public roads from Glasgow, and is

provided with railway communication by both the Caledonian and Glasgow

and South-Western Companies. The bed of the old Glasgow and Paisley

Canal has been converted into a rail

way; but a considerable traffic connected with the

agricultural, as well as the industrial institutions of the county, is

carried by steamboats on the Clyde.

A large number of streams and lochs and a

considerable extent of moorland are to be met with. Renfrewshire affords

good grouse and lowground shooting, and many anglers are to be seen on

the streams, though the sport is not very great. At one time the rivers

afforded good sport, but now they are largely rendered destructive to

fish life through pollution from public works. The principal rivers are

the "White Cart, the Black Cart, and the Gryffe. The first named rises

in the south-east corner of Eaglesham, and flows in a northerly

direction, and after receiving numerous "feeders" unites with the Black

Cart and the Gryffe at Inchinnan Bridge, and falls immediately into the

Clyde. The Black Cart has for its source Castle Semple Loch, and is

largely increased in its north-easterly course by the influx of several

streams. Rising on the north side of Creuch Hill the Gryffe has a course

of about 20 miles, and yields good fishing, but is not open to the

public. Among the other streams are the Calder, which rises in the Hill

of Stake, and after a run of 8 miles empties itself into Castle Semple

Loch, yielding trout varying in weight from ¼

to 2 lbs. each; the Earn, rising mainly in Binnen Loch, a 7 miles

long tributary of the White Cart; and the Daff, a little stream in the

parish of Inverkip, &c.

The lochs are numerous but not large. Castle Semple

Loch, in Lochwinnoch, is 2 miles long by 1 broad; Brother Loch and Black

Loch, in Mearns, are each about 2 miles in circumference; Loch Libo, in

Neilston, covers about 16 acres; Long Loch, between Mearns and Neilston,

is about 1½ miles long by 1½

miles broad; and Loch Thorn, in the parish of Inverkip, is 1½

miles long by 1½ miles broad. Besides these

are Loch Binnen and Goin, in Eaglesham; Queenside Loch, in Lochwinnoch;

and several large reservoirs, such as Stanley and Harlaw, for supplying

the various towns with water. The lochs occasionally yield good baskets

of pike, perch, eels, and trout of moderate size, while salmon are

sometimes to be got along the shores of the Clyde.

The little western county is well wooded. Ancient

records denote that it has been so from a very early date, and there has

always been a tendency among proprietors to maintain their plantations

creditably. Very little new land has been laid under wood for many

years, but the old plantations have been well managed, and, excepting

garden land and shrubberies, there are at present 5424 acres occupied by

trees. Orchard grounds extend to 53 acres, having increased 16 acres

since 1884. There are 135 acres of land used by market gardeners, or 4

acres less than in 1884; while 69 acres are occupied by nurserymen for

the propagation of trees and shrubs.

Population.

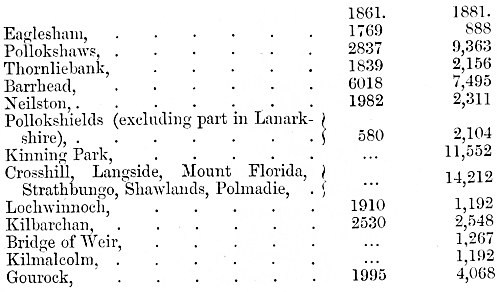

Though of comparatively small extent, Renfrewshire

contests with Edinburgh the distinction of being the most densely

populated county in Scotland, each giving as many as 1075 persons to the

square mile. At last census (in 1881), the western county contained in

all 263,374 people, of whom 226,073 inhabited towns, 19,044 villages,

and 18,257 rural habitations. The number of inhabitants at the end of

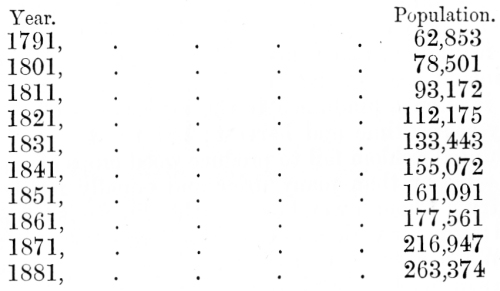

each decade since 1791 was as follows:—

A steady and substantial increase is thus indicated,

there having been an enormous advance of 200,521 during the past ninety

years. This is mainly due to the development of the industrial resources

of the county; but its choice situation and scenery, and its growing

importance agriculturally, have contributed not a little to the same

end. Of the entire population in 1881, 126,743 were males and 136,631

females. These were divided into 54,622 families, occupying 52,703

houses. Some 3319 males and 1371 females were connected with the civil

and military service or professions, 1141 men and 7623 women were

domestic servants, 9958 men and 294 women were connected with commerce,

3572 men and 934 women were connected with agriculture and fishing, and

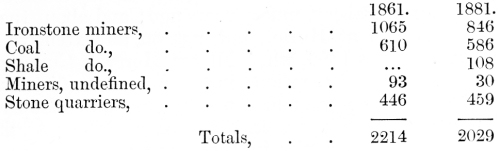

49,681 men and 21,734 women were engaged in industrial pursuits, or

dealers in manufactured goods; while there were 39,345 boys and 38,900

girls of school age. And to pursue this interesting analysis still

further, 7741 men and 15,547 women of those employed in industrial

handicrafts were engaged in the manufacture of textile fabrics, and 7986

men and 172 women were connected with the working of mineral substances.

Some 3284 men and 920 women were engaged in farming alone, and 813

farmers employed 865 men, 393 women, 118 boys, and 290 girls. The

Parliamentary constituency for the present year (1886) is— Eastern

Division, 8295 ; Western Division, 7750.

Climate.

As Greenock has from time immemorial been noted for

excessive rainfalls, it is natural to suppose that the county embracing

it should be generally moist as regards climate. As a rule, rainfalls

are heavier and more frequent on the banks of the Clyde than in the

eastern counties, and the causes of this are not inexplicable. The

prevailing winds blow from the southwest, and Renfrewshire, on account

of its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, as well as of its hilly

character, gets a lion's share of the rain. The watery clouds on the

eastward sweep are broken up by the hills, to which it is believed they

have a peculiar attraction, and rains that might otherwise be carried

further inland are thus retained in the west. Excessively wet weather is

often a hindrance to the agriculture of the county, especially at

seedtime and harvest; but the lower districts, as already hinted, seldom

fail to produce good crops of grain, roots, and hay—better than many

drier and equally fertile parts of the country. Though wet, however, the

climate is not peculiarly cold, and a greater variety of crop is

cultivated than in most districts. When autumn or spring sowing is

deferred, harvest is sometimes rather late, but in ordinary

circumstances, crops in the "laich lands," at least, come to the reaper

about the same time as those in the central counties. Further up, it

varies from a week to a fortnight later, and sometimes more, but the

higher reaches are less dependent on crop-growing than the lower. Of

course, the date of harvest is regulated by the character of the summer

— whether wet or dry, cold or warm. Like other counties, Renfrewshire

has its meteorological vicissitudes. A lengthened spell of dry weather

sometimes occurs, and is succeeded by a similar period of all but

constant drizzle. Winter is not so stormy as nearer the interior of the

country; still intense frosts are frequently felt; and they sometimes

linger long into spring in the upper districts, retarding field

operations.

Through the kindness of Mr Buchan, Edinburgh, we have

been allowed to make a few extracts from unpublished records of the

Scottish Meteorological Society, regarding the temperature, atmospheric

pressure, and rainfall, as registered at different parts of the county.

They are exceedingly interesting, and have an important bearing on the

subject proper of my treatise.

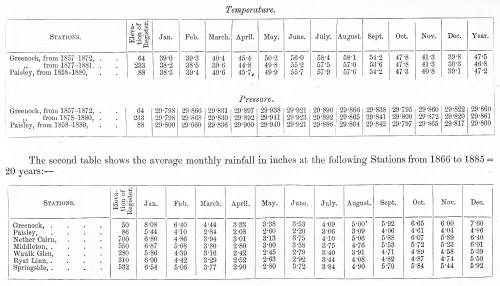

The first statement shows the mean monthly and annual

temperature, and atmospheric pressure, at three different elevations

above sea-level.

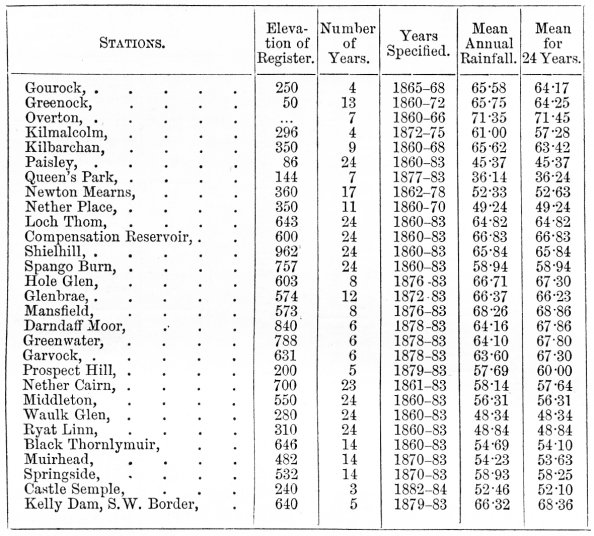

The third table shows the mean annual rainfall for

different periods, at various points, together with the calculated mean

rainfall for twenty-four years—from 1860-83:—

Geology.

The geological formation is of some interest and

importance. It shows a somewhat remarkable development of volcanic rocks

belonging to the Lower Carboniferous period, while it embodies an

important series of Coal-fields, situated to the north of the volcanic

area, between Houston and the eastern border of the county at Rutherglen.

The upper division is almost wholly intersected with trap, and this rock

also appears in other parts of the county. It belongs to various

species, viz., porphyry, greenstone, claystone, wacke, &c, and a coarse

conglomerate known as osmondstone. Much of it is of a rotten friable

nature. A narrow band of Old Red Sandstone extends round the western end

and up the northern border until within a short distance of

Port-Glasgow, but this variety of stone has not been found elsewhere.

The Coal Measures in the lower division, to which we have referred,

underlie an immense depth of earth, chiefly deluvial clay. Mine shafts

have in some instances been sunk through as much as 40 feet of a

superincumbent deposit, though at certain points the coal lies nearer

the surface. The minerals found are of a varied character, including

sandstone, limestone, aluminous schist, ironstone, bituminous shale, and

trap.

Soil.

Renfrewshire contains a larger variety of soils than

many more extensive counties. All the cropping land is of excellent

quality, while its lowland grazings are not to be equalled almost

anywhere. The land lying between the Clyde and a line running south from

Landbank to Kilbarchan, and thence east to Hurlet and Cathcart, is,

practically speaking, flat. The soil is composed of a deep alluvial

clay, intersected towards the centre by an extensive tract of peat moss,

supposed to have been deposited in brackish water at the same period as

the Carses of Stirling and Gowrie and a large part of Haddingtonshire,

the estuary of the Clyde having extended at that time from 5 to 6 miles

above Glasgow to Newton, where there are three well-defined terraces,

seemingly formed by the water having remained stationary for some

considerable time. Like the Carse of Stirling, some parts of the "laich

lands" are covered with a considerable depth of peat moss, which, as

will be subsequently seen, is gradually being brought under cultivation.

There are still three detached mosses, however, unreclaimed—Barrochain,

Dargavel, and Linwood, whose united area extends to several hundred

acres. The undulating portions of Cathcart, Eastwood, and Abbey parishes

consist of a strong clay inclining to sharpness, but their southern

boundary is depreciated by the prevalence of cold inferior clay.

The "gentle-rising" district, though in some places

hard, is mostly good useful land. Near river channels, as in the "laich

lands," there is a wealth of rich deep loam, and though chiefly used for

pastoral purposes, it is sufficiently good to yield heavy crops had the

climate been more suitable. The subsoil comprises a mixture of gravel

and stiff clay, the latter predominating in many parts.

The "hilly district," overlying a subsoil of gravel

and disintegrated volcanic rock, is largely composed of light land. Here

and there it is good, being slightly intermixed with moss; but its

composition, together with the climatic influences of the district,

adapts it more for pastoral or dairying than arable farming.

Except on the banks of the Clyde, no traces of animal

remains have been found. Taking the town of Renfrew as a centre,

however, with a radius of 6 or 7 miles, we form a semi-circle embracing

land of exceptional richness, by far the best cropping land in the

county. This line includes all the land south of the Clyde, extending

from midway between Langbank and Bishopton stations to Bridge-of-Weir,

Kilbarchan, and across the Fereneze Hills between Neilston and Barrhead

to Bushby. Outside that line the bulk of the land is devoted principally

to grazing for a distance of from 3 to 5 miles, while all the higher

lying land bordering on Ayrshire is essentially a sheep farming

district.

The State of Agriculture prior to 1860.

Since the introduction of improved farm machinery and

means of communication, great progress has been made in the agriculture

of the county. This will best be shown by a passing reference to the

state of the farming matters as they existed early in the century.

The county was at one time parcelled out to a much

greater extent than it now is or has been for many years. In the end of

last century, for example, there were no fewer than seventy-five

properties ranging in value from £100 to £6000. Fifteen exceeded £1000,

while a considerable extent of land was shared by proprietors possessing

under £100 per annum. About the close of last century, however, several

important changes took place in the ownership of land. One of the

largest estates was transferred to a new owner, and many small ones were

consolidated through the extension of larger properties. Well-nigh half

the proprietors acquired their lands by purchase within the last forty

years of the eighteenth century, the extent of land involved amounting

to nearly one-third of the whole shire. These changes led to an

enhancement of the revenue of the county, and between 1795, when there

were in all close on four hundred people owning land worth from £10

upwards, and the year 1810, its total valuation rose to £126,000.

Farms, as a rule, were small, and not so well

supplied with houses as those of most other Scottish counties. Farm

buildings were exceptionally long in assuming the convenient forms of

more modern times, and prior to 1830 few steadings were slated. In 1795

rents generally varied from £20 to £150, there being rarely any holdings

exceeding 100 acres in extent. Early in the century grazing farms

increased rapidly, reaching in several instances 200 acres. In the

higher reaches of the county some holdings approached 500 acres by the

advent of 1800, and rents advanced by leaps and bounds. The average

rental in 1795 was about 10s. per acre, but within ten or fifteen years

it had increased to fully 18s. Rents were then as now extremely

variable, ranging from 2s. an acre up to £5. Farms were held generally

on leases of nineteen years, and in many instances for longer terms.

Shortly after the close of the century, however, many proprietors

limited the lease to ten or twelve years with much acceptance to the

tenantry.

The tenants were generally bound to keep two-thirds

of their farms under grass in order to allow the soil ample rest, but

with this exception no hard and fast rules were laid down for the

(regulation of cropping. Farm implements were pretty much in keeping

with the age of which we write. Some sixty or seventy years ago the old

timber Scotch plough began to give place to the iron implement of

Berwickshire origin. The first threshing-mills were introduced about

1796, but the flail retained its hold for long after that date. These

mills cost about £50 each, and were capable of threshing six quarters of

grain per hour. Dairying was carried on to a considerable extent, and

the utensils in use for this purpose were in some respects believed to

be peculiar to the county. Some of the churns consisted of vertical

boxes, and the end of the churn staff was attached to one end of a

lever, by which the churn was worked after the fashion of a hand-pump.

This system of butter making, however, was greatly improved upon by the

introduction of a large horizontal churn, driven by water or horse

power. The horizontal churn, in consequence of its more equable and

constant motion, threw off butter of very superior quality to, and

greater quantity than, the more antiquated upright churn.

The early habits of farmers in the matter of land

tillage were somewhat lax. Late in the eighteenth century it was

customary to delay field operations till the season was too far advanced

for the successful cultivation of crops. This absurd practice continued

until a comparatively recent date, traces of ancient sluggishness having

been observable so late as the second decade of the present century. In

the rotation of crops no particular system was followed. Farmers had the

utmost freedom in this respect, but in the upper district two successive

crops of oats were generally followed by barley, hay, and three years'

grass. Before being ploughed the lea land was generally manured with

dung, or an admixture of earth and lime. In the lower division the

system of rotation differed but little from that of the higher district,

but the six-course shift was if anything more fashionable. Last century

an eight-course shift was no uncommon thing. In 1795 it consisted of (1)

oats, (2) fallow, (3) wheat, (4) barley, (5) beans and pease, (6) oats,

(7) hay, (8) pasture.

The principal cereal crops grown were oats and

barley, but wheat, beans, and pease were also cultivated in small

quantities. From 2½ bushels to 6 bushels was

the general allowance of seed oats per acre; from 2½

to 3½ bushels for barley; and wheat was seeded

at the rate of about 4½ bushels. Oats yielded

from 48 to 60 bushels per acre; barley, 36 to 48; wheat, 48 to 72; and

beans and pease, 30 to 48 bushels. Only a small extent of land was put

under green crop. Clover was never sown as a crop, and turnip husbandry

was all but unknown, so late as 1812. Carrots and cabbages were raised

on a small scale, while patches of flax met the eye in various parts of

the county, notably in the parishes of Lochwinnoch and Kilbarchan.

Potatoes, however, were cultivated with great success. They were

introduced about 1700, and seem to have been cultivated on the most

approved principles from the beginning. The ground allotted to their

growth was repeatedly ploughed and manured in the drill with from 40 to

60 cart-loads of Glasgow manure, which cost from 2s. 6d. to 3s. per

load. When potatoes were first introduced, the seedlings were planted

further apart than they are now, and generally yielded from 48 to 50

bolls per acre.

The cultivated land of the county was largely

interspersed with extensive tracts of waste and moss ground, the greater

part of which has been brought under the plough during the past fifty or

sixty years. About the beginning of the century some 13,800 acres, or

nearly one-eleventh part of the shire, was held in common among the

farmers, but the practice was early abolished, to the advantage, it is

said, of all concerned. In reclaiming the mosses and other uncultivated

lands, a great deal of draining had to be performed. The drains used

were either the narrow open casts, or narrow close drains filled with

small stones. They varied in depth from 2 to 3 feet, according to the

nature of the soil. On the flat carse grounds wide, sloped, open ditches

were extensively used to good purpose.

The manurial supplies of the county consisted chiefly

of lime and dung, no marl having been found within the county. Compost

was seldom made until comparatively lately, and lime, which was chiefly

imported from Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, cost 16s. per chalder of 16

bolls. The average amount of lime applied varied from 6 to 8, and in

exceptional cases reached 10 chalders per acre; and it was estimated as

early as 1812 that at least £12,000 worth of lime was annually used in

the county, exclusive of the expense of carriage in bringing it to the

fields. Glasgow, Paisley, Greenock, and Port-Glasgow were the principal

sources of dung.

One of the first things to raise the value of

property was the inclosure of land. Renfrewshire agriculturists were

amongst the first to take advantage of fencing, and there was less to do

in this direction after the advent of the present century than in almost

any other Scotch county. The inclosures in the arable district usually

embraced from 5 to 12 acres, but in the higher districts they

considerably exceeded that estimate. The higher districts were

cultivated only to a very limited extent. They lay mainly under natural

pasture, while the same may be said of fully three-fourths of the middle

division. The lower parts were more under the control of the husbandman.

Here natural pasture was early broken up, and amongst other crops a

considerable extent of hay was grown. A common allowance of seed ran

from 4 to 6 lbs. of clover and about I½

bushels of ryegrass, the average yield ranging from 200 to 250 stones

per acre.

The most neglected work on the farm was the "weeding"

of land. The importance of cleaning was ill-understood, and couch grass

and thistles and other pernicious weeds were allowed to sprout and

spread unheeded, greatly to the injury of the crops.

To complete the " contrast," we shall briefly refer

to the early resources of the county in live stock. Dairying appears to

have been the chief object of the farmer's attention from time

immemorial. The cows were speckled or spotted in colour, weighing from 4

to 5 cwt., and their produce was mainly disposed of in Glasgow, Paisley,

and Greenock in butter and butter milk. There were few cheese dairies.

These were devoted almost solely to the manufacture of Dunlop cheese.

The Alderney breed of cows was introduced in 1780, and crossed with the

Dutch breed and native cattle. They yielded richer cream, but a smaller

quantity of milk than the native breed, and the latter were thus

preferred. In some parts of the county the practice of letting cows for

the whole season was adopted, the rate about 1812 being from £13 to £14

per cow. Sixteen or seventeen years previously, however, the letting

rate was as low as from £6 to £7 each cow. The average yield of milk was

estimated at 7 Scotch pints (about 12 imperial quarts) per day, and that

of butter at about 4¼ lbs. per week, for six

months. The old system of management differed considerably from that of

the present time. The cows were fed in the house through the winter, and

generally allowed a few hours " airing " every forenoon. Farmers seemed

careless as to the importance of accumulating as much manure on the farm

as possible, but no sooner had they become alive to its value than the

ancient practice began to die out. The cows' rations in the winter

months consisted chiefly of oat straw with a small allowance of

potatoes, boiled with chaff or chopped straw. Hay was usually

substituted for the straw as the calving season approached, and the

supply of potatoes increased, while a little grain, meal, seeds, and

dust were generally added. Cows ranged in price from £15 to £21, heifers

from £3 to £10, and calves from £1 to £1. 5s.; while from £10 to £15 was

a common price for a bull. The calves were chiefly sold to butchers at

about 10s. a-head, but it would have been for the advantage, it is said,

of the farmers had they reared more cows than they did. Few cattle were

fattened for the butcher.

Sheep farming was long greatly neglected. Much

remained to be done in managing this branch of husbandry after almost

all other branches had been tolerably well improved. The sheep were

mainly of the blackfaced breed, and inhabited the more elevated parts of

the county. A Mr John Smith from Roxburghshire, farmer, Millbank,

Erskine, was singled out early in the century as the most enterprising

sheep farmer, having fed annually for several years from 300 to 400

Highland sheep on turnip fields. In 1810, some 500 merino sheep were

imported from Spain, and did well in Renfrewshire. They soon spread

widely over the county. They yielded rather more wool of a much finer

class than the original breed of the district, and brought good prices

in the lean market—for breeding purposes. Fifty rams realised an average

price of £15, and 200 ewes brought about £10 each, sold by auction, the

purchasers being mostly men of the neighbouring counties. Had such fine

wool-producing sheep been more extensively used and carefully managed,

it is believed a powerful impetus would have been given to the

industrial trade of the county, and that a large expenditure of money

obtained by wool-producers in other parts of the county would have been

pocketed by the farmers of the west.

That great attention was devoted to the rearing and

management of draught horses may be accepted as a matter of course. No

county evinced an earlier or more ambitious predilection for powerful,

active sound-going agricultural horses than Renfrewshire. Some eighty

years ago, 40 guineas and 50 guineas were common prices for farm horses.

A pair ploughed at the rate of a Scotch acre per day, and in carting

over good roads a ton was the usual burden imposed. They were fed on

oats and oat straw during winter, and on pasture and cut grass through

the summer and autumn months. Carters' horses were allowed hay, oats,

and beans. The use of oxen, either for ploughing or carting, had been

long abandoned before the advent of the present century. Few pigs or

poultry were kept.

The cost of labour in those days was very small,

compared with that of to-day. Still, during the first ten years of the

century, it increased very rapidly. In 1804, men servants, exclusive of

their board and house room, received £15 per annum ; women servants, £6;

day labourers, 1s. 11d.; women, in harvest, per day, 1s. 8d. During the

next six years these rates had increased nearly a third, and other items

of labour became correspondingly dear. The cost of reaping an acre of

corn, for example, was computed at 12s., while the threshing of it cost

about 3s. 6d. per qauarter. Ploughing and harrowing per acre cost from

£1 to £1, 10s. mowing hay, 4s. to 5s.; digging the ground, £4 to £6 ;

and a day's work of a horse and cart, with driver, 7s. to 8s. The hours

of labour were similar to those of the present time.

Progress of the Past Twenty-five Tears.

Notwithstanding the progress made prior to 1860, a great deal of useful

work has been done since then. Land that was formerly utterly barren has

been converted into a productive state; houses that were all but

uninhabitable have been swept away; and fields of ungainly and awkward

shapes have been advantageously transformed.

It is estimated that from 400 to 500 acres of moss

and swampy land has been reclaimed since 1857 ; while a large extent of

cultivated land has been increased in value by means of draining,

liming, and fencing. About 100 acres of sterile moss, in the

neighbourhood of Paisley, belonging to Lord Dunglass, were taken by the

Cleaning Department of the Glasgow Corporation in 1879, on a lease of

thirty-one years, at a nominal rent. Immediately on acquiring the land,

the Corporation began draining it. The drains were cut as deeply as the

soft nature of the ground would permit—4 spadings in the main, and 3 in

the common drains. This partially dried the ground, and after a few

months of summer weather, the drains were deepened to the requisite

depth—5 feet. The man who took out the last spading laid the tiles as he

proceeded, and to prevent them from rising through the pressure of the

sides of the drain, the lad who handed him the tiles immediately placed

a sod on them and stood on it. The tiles used were of the dwarf-flanged

description. When properly laid they are less liable to choke than other

kinds of tiles. The flat wooden sole and common horse-shoe tile have

been sometimes used in similar reclamations, but the floating fibre

catching upon the wood sometimes chokes the drains. The drains were cut

16½ feet apart, and the moss was carefully

subsoiled,—the original surface being kept on the top. The sods were

broken by means of hoes; a squad of the Glasgow "unemployed" having been

engaged for the purpose. The land was heavily top-dressed with road

scrapings containing a large percentage of lime, but no additional

supply of new lime was allowed. The draining cost about £20, and

subsoiling and hoeing about £10 per acre. Such an expensive reclamation

is seldom undertaken, but it is wise, if the subject in hand is good, to

do the work thoroughly. It often happens—and it seems to have been the

experience of the Glasgow Corporation—that the costliest work is the

cheapest in the end. The Corporation's land in its original state was

utterly worthless, and now it is valued at from 30s. to 40s. per acre.

Within a year after the work was begun, it was placed under potatoes,

and also in the following year, the seed having been planted solely by

manual labour. These two crops firmed it, so that it would bear horses

shod with leather and gutta-percha sandals in the third year, and it is

now under regular cropping rotation. In the results of the reclamation,

the most hopeful anticipations have been realised, a satisfactory profit

having already been obtained from the land.

The new land is of greater value to the Corporation

than it would have been to an ordinary tenant, affording as it does an

outlet for the scrapings from the macadamised roads of the city, which

forms an excellent dressing for mossland.

Similar improvements have also been carried out on

other estates in this neighbourhood, though not so recently as those

just referred to. Some thirty years ago, Mr Spier of Black-stone

reclaimed the moss of that name, converting 130 acres of bleak dormant

earth into good active soil. About the same time another waste, called

Plantation Moss, extending to about 40 acres, was fertilised and put

under crop. Since then, too, the spirit of improvement has been actively

at work in other districts. Kilmalcolm Farm, Hillside, for example, has

been enlarged by the addition of some 50 acres of new ground, and

improved by the draining of swampy and coarse pasture land. In the

parish of Neilston Mr Robert Holms reclaimed some 70 acres, and besides

these vast improvements have taken place in the condition of cultivated

land. In every district of the county a great deal of draining and top-dressimg

has been done. The introduction of the railway lent a powerful impetus

to cultivation. It opened up access to the manurial repositories of

Glasgow, Paisley, and Greenock, and these have been widely taken

advantage of by farmers. City manure has been extensively used for many

years with good results.

Some twenty-five or thirty years ago the wet marshy

meadows which met the eye in several districts had to be cut by the

scythe and gathered by means of a hand-rake. Since then, however, they

have been largely drained, and sown down with timothy and other valuable

grasses, and cutting is now performed mainly by sowing machines, which

were partially unknown twenty or thirty years ago.

But before going further we shall see what progress

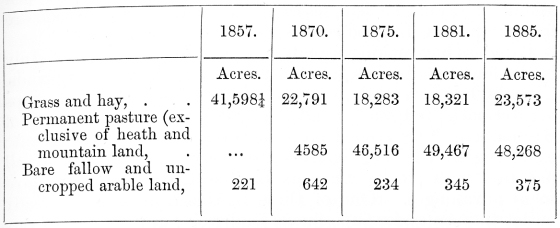

really has been made in the direction of extending cultivation. In 1857

there were 75,151 acres under cultivation, including bare fallow and

grass; in 1868, 86,531; in 1874, 89,493; in 1881, 94,339; and. in 1885,

95,529. There has thus been a steady and substantial increase during the

periods indicated. Since 1857 the cultivated area appears to have

increased no less than 20,378 acres. It may be explained, however, that

the statistics for that year did not include holdings under ten acres in

extent, But since 1868 there has been an advance of 8998 acres, which,

spread over the seventeen years from 1868 to 1885, show an annual gain

of fully 529 acres. During the past four years the cultivated area has

developed at the rate of close on 300 acres per annum; but, of course,

these figures give no indication as to whether crop-growing has

increased or diminished.

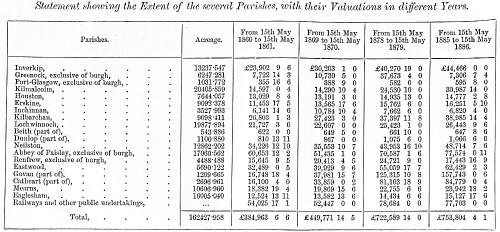

The statement on page 18 shows the extent of the

several parishes, together with their valuations in different years, and

gives the results of the recently improved area of the county.

The table exhibits a remarkable advance in the

valuations of most of the parishes. Down to 1879 every parish made

distinct progress, with exception of Inchinnan and Abbey. These

decreased £3122, 4s. 4d. and £9218, 11s. 2d. respectively. Such

diminutions are somewhat extraordinary, but they are not due to strictly

agricultural causes. It will be observed that the value of Inchinnan

parish made an enormous bound between 1861 and 1870 ; and that,

notwithstanding the striking fall referred to, its valuation in 1879 was

considerably above that of 1861. The parish of Abbey, whose loss occurs

between 1861 and 1870, recovered itself, and resumed progress before the

advent of 1879. Six parishes have decreased in value since 1879, the

fall in the case of Greenock being no less than £30,366, 16s. 8d. It

will be seen, however, that the Greenock parish made quite an

exceptional rise between 1870 and 1879 ; but after all, the present

valuation is less even than either that of 1861 or 1870. The other

parishes which have fallen off are Houston, Inchinnan, Beith, Dunlop,

and Renfrew. The last-named parish has decreased £7277,

12s. 3d. since 1879; but the fall in other cases mentioned is

comparatively trifling. It would be difficult to account with certainty

for the decline of recent years, more than for the striking fluctuations

prior to 1879; but we suspect the depreciation in the value of land has

had something to do with it.

Despite the fluctuations which we have shown,

however, the total valuation of the county has nearly doubled since

1861. Net increase, £369,940, 17s. 7d.; since 1870 it has advanced

£304,032, 9s. 9d.; and since 1879 it has increased £31,214,

10s. 1d. In live stock, too, distinct progress has been made. The

stock have responded satisfactorily to increased attention, and more

liberal treatment on the part of owners; and to-day the county takes a

more prominent stand in the "battle of the breeds" than ever it did

before. Little or no alteration has occurred as regards the breeds of

stock kept; but it is worthy of note that Border Leicester sheep have

obtained a footing on several farms.

Details of Improvements and Systems of Management.

It was recently my privilege to visit a number of

leading farms and estates in the county, and to make personal inquiry as

to the improvements carried out, as well as to the prevailing systems of

farming, and this, together with elaborate correspondence with

landlords, factors, and farmers, enables me to give under this head one

of the most interesting sections of my report. I have before me,

moreover, the information obtained by Mr James Hope for the Royal

Commission in 1880, and will thus briefly refer to the methods of

management adopted on the principal estates and many of the leading

farms in the three divisions of the county.

The Hilly District.

This district forms by far the largest division. It

includes the entire parishes of Inverkip, Greenock, Port-Glasgow,

Kilmalcolm, Eaglesham, Mearns, and the greater part of Neilston and

Lochwinnoch, as well as portions of several mainly lowland parishes. The

medium elevation is from 500 to 600 feet, but being largely composed of

disintegrated trap rock, the soil where sufficiently deep is

fertile—generally light active land. It is worthy of remark, however,

that Inverkip, though farmed similarly to the neighbouring parishes,

contains an entirely different class of soil from that of the East

Garvock Hills. Much of the lower lands lie on Old Red Sandstone, and a

good piece of grazing land is scarcely to be found. The soil, although

apparently fairly good and firm, conceals a large amount of water which

is very difficult to remove by under-drainage. As a result of this,

crops are much later than one would anticipate from its low situation

and proximity to the sea. The rainfall is heavier here perhaps than in

any other part of Scotland— certainly the wettest part of Renfrewshire.

It ranges annually from 45 to 65 inches, and is very evenly distributed

over the year. The district is almost entirely devoted to dairying and

sheep farming, the former constituting the staple occupation.

The greater part of the hilly district is owned by

Sir Michael Robert Shaw Stewart, Bart. His possessions, the largest in

the county, extend to some 25,000 acres, of which 11,000 are arable,

12,910 pasture, and 1090 woods and forests. They have been considerably

improved during the past twenty or thirty years by draining, building,

and reclaiming; and, as a rule, the tenants pay interest on the money

expended by the landlord in drainage. The estate comprises in all 99

farms, which may be classed thus—2 above 1000 acres in extent, 3 from

500 to 1000 acres, 27 from 200 to 500 acres, 29 from 100 to 200 acres,

17 from 50 to 100 acres, 14 from 20 to 50 acres, and 7 under 20 acres.

These are usually held on lease, with 40 days' notice to quit, but

judicious liberty is given to tenants in the management of their farms

so long as they conform to the rules of good husbandry. The rents of

arable land vary from 20s. to 35s. per acre, and are all fixed and paid

in money. Up till 1880 they increased from 15 to 20 per cent.; but it

was generally considered that the additional accommodation required by

the tenant exhausted any advantage to the landlord which the rise gave.

Since then, some liberal concessions have been made (including 10 per

cent. reduction on the farm rents of the half year), and the tenants

have all along obtained assistance in lime and manure when such were

needed. No noteworthy change has occurred in the system of farming over

these estates since 1860, but it is freely admitted that the agriculture

of the district has vastly improved since then. The six-shift rotation

is the one usually adopted, but tenants are encouraged to let their land

lie as long under pasture as possible. The crops grown consist of oats,

a little barley, potatoes, turnips, and hay; while milk, potatoes, oats,

and hay are the descriptions of produce generally sold. Farm stocks

comprise Ayrshire cattle, blackfaced sheep, Clydesdale horses and pigs

of various sorts. Cattle and sheep are pretty extensively bred on the

estates, but comparatively few are fattened.

The parish of Kilmalcolm is an extensive district in

which mixed husbandry is carried on. It contains some very good farms,

and one of these is the farm of Dennistown, tenanted by Mr John Thomson.

Comprising fully 130 acres, it is rented at 35s. 6d. per acre. This,

however, is far above the average rental of the parish. The soil is

light and friable, overlying a sandy " till" or gravel. This class of

soil predominates over the district, but it is here and there

intersected with swampy flats and peat moss in the valleys. Along the

sides of the River Gryffe, which drains the entire length of the parish,

fine loamy soil prevails of considerable depth. These level parts have

almost all been drained by the proprietor within the past few years. On

Dennis-town farm the eight-course shift is followed, viz., oats after

lea, potatoes or turnips, oats, ryegrass-hay, and pasture for four

years.' Oats yield 30 bushels per acre, weighing from 38 to 40 lbs. per

bushel; potatoes from 6 to 8 tons, turnips about 15 tons, and hay 1½

tons. The stubble land is ploughed in October and November, and allowed

to lie thus exposed all the winter. It is harrowed well, and ploughed

again between the middle of March and the first of May, as opportunity

occurs. Mr Thomson prefers second ploughing to grubbing for two

reasons—(1) because the rock is so near the surface that the grubber

tines are extremely liable to be broken or bent, and (2) because the

land is in a better state for sowing after being ploughed. Being for

green crop, it is manured with from 20 to 25 cubic yards of farm-yard

dung, or about 30 tons of police manure, supplemented with from 2 to 3

cwt. of bone phosphates or special manure, according to the quality of

the dung applied. For Champion potatoes, the dung is usually ploughed

down, at the rate of from 30 to 40 cubic yards, during winter, and 1½

cwt. of phosphate guano, 2 cwt. bone phosphate, ½

cwt. sulphate of potash are added just before planting in spring.

The more economical way, however, of manuring in the drills, is adopted

for other varieties of the favourite esculent, less artificial manure

being required than when the dung is ploughed down in winter. When the

dung is applied in winter, it is liable to be brought to the surface

again, and partly wasted by second ploughing in spring, but to prevent

this, Mr Thomson drills the stubbles (what is sometimes termed

"ribbing"), which covers the dung without burying it. In spring it is

harrowed with a common harrow across the drills, and then ploughed down.

This is a very exceptional system of preparing land for potatoes, but it

is one which thoroughly answers the purpose.

Since 1860 the proprietor has erected a handsome

steading on this farm, free of interest, the tenant doing all the

cartage. All the interior fences have been rooted out, and the fields

rearranged and fenced anew. A good deal of land has been drained at the

mutual expense of the landlord and tenant. As regards live stock, the

farm is well plenished. The dairy stock are let to a bower or dairyman

at £15, 10s. per cow per year. The owner supplies the bower with

turnips, bean meal, bran, hay and straw for the cows. The calves, except

those that are required to keep up the stock of cows, are sent to the

butcher as soon as they are dropped. The produce of the dairy is sent to

the market every morning in the shape of sweet milk, cream, and skim

milk; and what is not disposed of is churned, and the butter milk is

sold. This system is widely adopted in the county. A few Leicester sheep

are kept on the farm, being summered in the grass parks, and wintered on

pease and oats, and hay when necessary. Excepting a few reserved for

breeding purposes, the lambs are sent to the butcher in June and July,

and the aged ewes are similarly disposed of in November.

Along the south-western border of the county are the

estates of Carrath and Garthland, the property of Mr Macdowall. Carrath

covers some 1600 acres of Kilmalcolm ; while Garthland, comprising about

1000 acres, lies within the parish of Lochwinnoch. The former consists

of 800 acres of arable land, 90 acres pasture, 650 acres hill and moor,

and 60 acres of woods and forests. The smaller estate is made up of 300

acres of arable land, 250 acres of meadow, 275 acres of permanent

pasture, 100 acres of moorland, and, 70 acres

of woods. Dairying and sheep farming are the distinctive features of the

agriculture on this property. The latter is not largely pursued, there

being only one farm on the Garthland estate and three on Carrath. The

soil of the latter estate is of a sharp light character; but there is a

variety of land on the Lochwinnoch estate—rich loam, heavy clay, sharp

gravel, and moorland. Some important changes have occurred since 1860,

the landlord having expended money liberally in increasing the comfort

of his tenantry. He has rebuilt many old fences, without interest, but

on drainage improvements he advanced money at 6§ per cent, A good deal

has recently been done in the way of improving the farm buildings. On

Carrath there are eight farms, two of which range in size from 200 to

500 acres; while three extend from 100 to 200 acres, and three from 50

to 100 acres. Garthland comprises only three farms, two of which range

from 100 to 1200 acres in extent, and one is less than 100 acres. These

holdings are tenanted on a lease of nineteen years, without stipulation

as to notice to quit, and the tenants usually implement the full

conditions of their leases. Rents on Carrath average about 17s. 6d. per

acre for arable land, £1, 15s. for pasture land, and 3s. 6d. for hill

and moorland. They are dearer on the Lochwinnoch estate. Arable land

averages about £1, 15s.; pasture, £2, 5s.; hill and moorland, 7s. 6d.;

and meadow, £1. All the rents are fixed. The conditions of entry are

similar to those prevalent on many other Scotch estates. The incoming

tenant takes over the farm-yard manure at valuation on entering the

farm, and has to accept valuation of the same on leaving. The way-going

tenant has to leave the farm in a certain rotation. There has not been

much alteration made recently on the systems of farming on the estates;

but on the heavy soil at Garthland there is less green cropping now than

formerly, owing to the exceptionally wet seasons of late years, the

manure being to a large extent ploughed down with lea. The crops grown

are oats, potatoes, turnips, and hay, the course of rotation pursued

being the seven-years' shift. Dairy produce, potatoes, and hay are the

principal commodities sold off the farms. The stock kept are the same as

those on the estate of Sir M. E. Shaw Stewart. Cattle are bred for

keeping up the dairy stocks, but very few for sale. A considerable

number of both cattle and sheep, however, are fattened on the pastures.

The farm of Netherhouses, in the parish of

Lochwinnoch, in conjunction with the adjacent farms of High and Low

Barford, and other grass lands on the estates of Garthland, Lochside,

Castle Semple, Auchengrange, &c, were occupied till Whitsunday 1886 by

Mr William Bartlemore. Their united area is about 250 acres, all arable,

mostly under pasture. Latterly a good portion of Barfords has been

devoted to the growth of timothy hay, which has become a favourite and

remunerative crop in the county. The farm of Bourtrees adjoins that of

Netherhouses, and these two holdings have been owned and occupied by the

Bartlemore family for upwards of a century. It is noteworthy that this

family are a branch of the Patons of Swinlees, in the adjoining parish

of Dairy, Ayrshire, whose name is inseparably associated with the

breeding of Ayrshire cattle. The Patons rank amongst the most successful

breeders of the renowned dairy breed, and the Bartlemores seem to have

inherited not only their fancy, but also much of their enthusiasm.

During the past eight years Mr William Bartlemore has been one of the

most prominent breeders of Ayrshires in the county. In 1884 and 1885 his

animals won over £500, exclusive of plate and medals, and that in the

hottest fields of competition at the Scotch and English National

Exhibitions, at the London Dairy Show, and at the leading shows in the

west of Scotland.

The soil on these farms is chiefly of a clayey

nature, intersected to some extent with patches of heavy loam, admirably

adapted for grazing purposes. The average rental, including the

adjoining grass lands, is 38s. per acre. A dairy stock is kept at

Netherhouses, The produce until recently was sold as cheese, but Mr

Bartlemore found it more convenient and profitable to send the milk

daily to Glasgow. A small portion of the farm was tilled for corn and

root crop ; but the major part was grazed by sheep, store cattle, and

back-calving Ayrshire cows. For about thirty years prior to his death in

1883, the late Mr Robert Bartlemore, a former tenant of these farms, was

an extensive grazier. His total rental in 1880 was about £560. He kept

ten or a dozen cows, whose produce was made into cheese, but his

principal pursuit was grazing. He grazed about 250 head of cattle every

year, and occasionally a few scores of blackfaced ewes, with cross-bred

lambs. One-fifth of the cattle were home-bred Ayrshires, due to calve in

the months of October and November; while the remainder were mostly

bought in lean in spring. These were largely purchased at Muir-of-Ord

and other northern markets. He found north country cattle to do well

with the change of climate and keep, and they seldom left a smaller

profit than from £4 to £6 a head, sometimes more. In 1879 the margin was

considerably diminished by the increased value of lean stock, but even

that year was not unprofitable. Any cattle bought after spring were

generally brought from the islands of Skye and Islay. The ewes were

purchased in the month of October, and mated with a whitefaced tup, and

both they and their lambs were sold off fat as early as possible next

year.

Great improvements have been effected on these farms

during the past thirty years. They have all been thoroughly drained with

common tiles and soles, and the open ditches and water runs which

formerly intersected the farms have been tile-laid and covered. The

landlord paid for the tiles and their carriage, and the tenant cut and

filled the drains at his own expense. The quality of the land has thus

been greatly improved, while much good work has been done since 1860 in

fencing.

On the farm of South Halls, also in the parish of

Lochwinnoch, dairying is more exclusively practised than on Netherhouses.

The dairy herd includes some twenty animals, and it is mainly maintained

by home-breeding. In his report to the Royal Commission in 1880, the

tenant, Mr John Harvey, stated that he obtained 500 gallons of milk from

each cow per annum, which was equivalent to £14 per head. His average

outlay in food not grown on the farm approached £5 per cow, the material

used consisting of, as a rule, bean and Indian meal. For the work of

twenty cows he employed two female servants, whose united wages, besides

board, was about £35. When he entered the farm some twenty-two years

ago, the same class of servants cost only £4, 10s. each, which

represents an advance, notwithstanding the downward tendency of recent

years, of about 50 per cent. since 1863. The dairy produce is sent to

Glasgow as sweet milk, and in the summer of 1880 he got 7d. per gallon

for it, which was the highest price going. Out of that return he paid

one penny for railway carriage, with the result that 250 gallons during

summer brought him a clear return of £6, 6s., and a like quantity in

winter realised £8, 6s. 8d., which made the total return per cow up to

£14, 12s. 8d. The gross annual sum received for milk amounts to about

£290, while he usually disposes of eight cast cows each year for about

£144, and this sum, together with about £150 for timothy hay, represents

the entire revenue of the farm. He ploughs as little land as possible,

because the cost of labour and manure would, in addition to rent, leave

him no profit.

Pursuing our north-western course, we next enter the

parish of Neilston, in which both agricultural and pastoral farming are

pretty largely carried on. One of the principal farmers in this district

is Mr John Holm, Japston, who holds no fewer than three farms, with a

united area of 450 acres. Of these 250 acres are arable, and 200 acres

pasture, each holding varying in rent according to the quality of the

land. On one holding the tenant pays 60s. per acre, another 33s., and

another 20s. for arable land, and the pasture ranges from 10s. to 15s.

The soil is of a mixed clayey character, and the climate is late and

moist. Mr Holm ploughs very little, having adopted the system of

irrigating meadows with satisfactory results. The principal odder crop

grown is timothy hay, which, together with other varieties of hay,

usually occupies about 60 acres each year. Only some 25 acres are

devoted to the growth of oats. Generally speaking, however, there is

abundance of straw produced on the farm, but the grain is usually light.

For the turnip and potato crops the land is ploughed in the autumn, and

grubbed in spring, and is dunged chiefly with farm-yard manure. Turnip

land gets a little nitrate of soda in addition to the dung to start the

young plant, which is often stiff in coming away. A good many

improvements have been executed on this farm since 1860. Over £2000 have

been expended by the landlord and tenant together in building, draining,

fencing, &c. The landlord erected an excellent steading, free of cost,

and drained extensively, charging the tenant 5 per cent. interest on the

latter. The farm of Japston, like that of Netherhouses, has long been

creditably connected with the breeding of Ayrshire cattle, for which the

tenant has won many distinguished prizes at local and other shows. The

dairy cows on this farm, and also in the surrounding district, are

liberally fed with bean meal and bran. A little draff is used where

sweet milk is the main product; but in this immediate neighbourhood the

milk is nearly all churned, and disposed off in the shape of butter and

butter milk.

The system of farming in this district has not

changed materially since 1860, but less land is ploughed, and more

timothy hay grown than formerly.

In the same parish is the farm of Caplaw, tenanted by

Mi-Matthew Templeton. It embraces 300 acres, is wholly arable, and is

rented at about 20s. per acre. Since 1860 the rent has increased about

£40. Lying at an elevation of from 600 to 750 feet above sea-level, it

comprises mossy light soil, and is worked under a six-course shift,

viz., oats, potatoes and turnips, oats, hay, and two years' grass. In

good seasons crops yield well, but, as a rule, the grain is light in

weight and dark in colour. Land for green crop is fallowed in autumn. In

spring it is ploughed, harrowed, and grubbed, and again harrowed until a

good tilth is secured. The manure, mostly dung, is applied in the drill

for both turnips and potatoes. Since Mr Templeton entered the farm some

six years ago a considerable portion of it has been drained and fenced,

while by a better system of agriculture generally he has enhanced its

value. The landlord, moreover, repaired houses, and built some new ones,

the tenant performing the cartages. Ayrshire cattle are kept, and until

the last two years above twelve calves were reared annually. The only

stock fattened are cows that become unfit for the dairy, and these when

fat weigh from 3½ to 5 cwt. each. Besides the

cattle reared on the farm, a good many cows are from time to time bought

in to keep up the dairy herd In summer the cows are fed on grass, and in

winter they receive a liberal allowance of boiled food, oat straw, hay,

turnips, and bean and linseed meal, and bran. They are fed three times a

day, excepting newly calved cows, which get a few turnips about

mid-forenoon and again in mid-afternoon. This system of feeding

allows the animals ample resting time, which is an important point in

stock management. The, dairy produce is sold in Paisley in the form of

butter and butter milk. No sheep are kept, but the pasture is

occasionally let for wintering hoggs, for which the usual remuneration

is £6 per score. The farm work is performed by four horses, three of

which are Clydesdales. In replying to the Royal Commission inquiries in

1880, Mr Robert Gillespie, farmer, Boylestone, stated that he owned a

herd of forty dairy cows, valued at £20 per head. About twelve cattle

were reared annually on the farm, while some twenty were bought in. The

yield of milk per cow was about 8 imperial quarts per diem, and it was

sold as milk. He neither made cheese nor butter. Keep for each cow cost

about £14 per annum, the half of which was grown on the farm. The annual

sale of milk, which was delivered to the purchasers on the farm, yielded

about £700, and the sale of cast cows £200; but, with exception of about

100 bolls of corn, these constituted the entire marketable produce of

the farm.

An important change in the system of farming in this

district since 1860 is the production of winter milk, which many people

believe does not pay the farmer. Another change is the reduced area of

land devoted to the growth of potatoes, for which there has been

inadequate demand of recent years. Though ameliorations have been

effected more or less on every farm, there is still a great deal of land

in need of improvement. Additional draining would be of great service,

while much of it might he limed and fenced with advantage to all

concerned. Irrigation, where practicable, suits the district well, and

would be more extensively adopted if sufficient water supply could be

obtained.

The estate of Eaglesham, with an area of some 16,000

acres, belonging to Mr Allan Gilmour, comprehends almost the entire

parish of that name. Excepting 160 acres of wood, it is equally divided

between arable, permanent pasture, and hill land. Three branches of

farming are thus practised within it,—corn-growing, dairying, and sheep

farming. It contains forty-four farms, several of which are very

extensive. Four holdings are over 1000 acres in extent; two range from

500 to 1000 acres, nine from 200 to 500, twenty-three from 100 to 200,

five from 50 to 100, and one is less than 20 acres. Some improvements

have been carried out on all the farms within the past twenty or thirty

years, draining, which was the principal work, being executed at the

landlord's expense, the tenant paying 5 per cent. on the outlay. They

are held on leases of nineteen years, though not subject to any strict

regulations as to cropping. No particular rotation is thus followed. The

crops consist of oats, green crop, oats, and hay, followed with from

four to eight years' grass. The average rental of hill pasture runs from

3s. to 8s. per acre, arable land being held at from 20s. to 50s. During

the thirty-five years preceding 1880, rents increased 30 per cent., but

since then both permanent and temporary reductions have been granted.

There has not been much done in the way of enclosing land of recent

years; still the land is tolerably well fenced. Several thousand acres

of moorland are enclosed. The tendency of the past ten or fifteen years

has been to increase the extent of permanent grass, and save labour and

risk of crop-growing. Almost the only produce sold is dairy produce,

sheep, and lambs. Crops yield irregularly, the return of oats varying

from 35 to 45 bushels, turnips from 12 to 20 tons, potatoes from 3 to 6

tons, meadow hay from 2½ to 3 tons, and mixed

seeds 2 tons per acre. The live stock consists of Ayrshire cattle,

blackfaced and Cheviot sheep, Clydesdale horses, and a few Berkshire

pigs. Few sheep or cattle are fattened.

On the Eaglesham estate, Mr James Mather occupies 150

acres, which is the extent of the farm of Waukers. With exception of 10

acres of meadow, the holding is entirely arable, and is rented at £2,

13s. per acre. Only some 10 acres are broken at a time, and it is

cropped thus:—oats, green crop, oats, hay, and six years' grass. The

land yields fair crops as a rule, oats weighing from 37 to 40 lbs. per

bushel. Land for turnips and potatoes is prepared in the usual way, and

is manured entirely with home-made manure. The farm has been skilfully

managed, and by the combined enterprise of the landlord and tenant,

substantially improved during the past twenty-five years. The landlord

drained the greater part of it, the tenant paying 5 per cent. interest

on the outlay. The farmhouses were repaired solely at the landlord's

expense. Ayrshire cows to the number of forty are exclusively kept for

dairy purposes. They are principally fed with boiled and raw turnips and

potatoes, along with draff and bean meal and other artificial stuffs.

The dairy produce is wholly sold in Glasgow as sweet milk.

Middle District.

The middle or "gentle rising" district is less than

one-half the extent of the division we have just described. It embraces

the parishes of Cathcart and Eastwood, with parts of the parishes of

Abbey, Kilbarchan, Houston, Erskine, Inchinman, and Renfrew; and as

regards diversity of surface, is one of the most beautiful districts in

Scotland. It has been thus described:— "Little gentle hills gently

swelling in endless variety, interspersed with various coloured copses,

often watered at the bottom by winding rivulets, in different and

changing forms, meet every turning of the eye; and few inland views

perhaps surpass in richness and variety those which present themselves

from the top of every one of those gentle eminences which are so

beautifully scattered around the town of Paisley."

The two small parishes of Eastwood and Cathcart form

the" extreme eastern corner of the county, and resemble each other

closely as regards farming. The farm of Shaw Moss, containing 260 acres,

and tenanted by Mr Alexander Aitkenhead, in a manner combines the two.

It extends into both parishes, and is one of the most important farms in

the district. It comprises sandy loam soil and a sprinkling of moss, and

was rented at £620 in 1880. Formerly it was held on a lease of ten

years, but for some time past the lease has been abandoned. The farm is

essentially a crop-growing one, and though the four-course shift—oats,

turnips, oats, and hay—is the system adopted, the tenant is not

restricted to any particular rotation. Stock breeding is not practised;

horses, cattle, and pigs being bought in and sold as required. Some £50

is annually spent in artificial feeding stuffs, while artificial manures

are used to the value of £100. The thrashing of grain is done by steam

power. In the early part of his tenancy Mr Aitkenhead made extensive

improvements in draining and solidifying moss land. He also made several

new roads, and erected a considerable stretch of fencing. The gross

annual cost of labour on the farm has risen about 10 per cent. since

1870.

The estate of Hawkhead [This

estate has been sold, mostly in allotments, since the above was written.]

—though mainly in the parish of Abbey—also extends into the parishes of

Neilston, Eastwood, and Renfrew. It comprises some 4400 acres, of which

3650 are arable, 550 pasture, and 200 under wood. The soil is partly

stiff loam and light sharp land, the former resting on a subsoil of

clay, and the latter on freestone. The property is divided into some

twenty-six farms. Ten range from 50 to 100 acres in extent, ten from 100

to 200, five from 200 to 500, and one from 500 to 1000 acres.

Improvements have been extensively carried out during the past

twenty-five years. The landlord expended the money required in the work,

charging the tenants interest on fencing and draining. The farms are

held on leases of nineteen years, but no regulations as to cropping are

strictly enforced. Rents vary considerably. Arable land is let at about

40s., and pasture at about 15s. per acre, the average rental being about

37s. 6d. These are all payable in money. During ten or twelve years

preceding 1880 they increased about 10 per cent. The way-going tenant

gets payment for grass seeds sown with the last corn crops, and also for

all farm-yard manure made on the farm during the last year of his lease.

Within the past twenty years the agriculture of this estate and district

has advanced very greatly. This is observable in every phase of farming.

The land of the county generally has improved as regards cleanness,

while creditable progress has been made in the live stock of the

district. Most of the tenants on this estate work their land under the

five-course rotation, viz., oats, green crop, wheat, clover hay, and

pasture, but less land is cropped than was the case a few years ago.

They are allowed to sell the produce of their farm unrestrictedly, and,

as a rule, good crops are raised. The average yield of wheat in good

years is about 5 quarters per acre, while 4½

quarters is a common return of oats per acre. Turnips yield about 15

tons per acre, and potatoes, which are more irregular than other crops,

vary in yield from 4 to 10 tons. Of clover hay 2 tons per acre is about

an average return.

One of the leading tenants on the estate is Mr

William Bowie, Blackbyre, who farms 257 acres of arable land in the

parish of Abbey. It is worked under a four-course rotation, the crops

grown being oats, potatoes and turnips, wheat, clover hay and pasture.

The rental is £565. Ayrshire cattle are kept purely for dairy purposes.

During summer they are fed in the house, principally on grass,

supplemented with feeding stuffs. In winter they get turnips, hay, bean

meal, brewers' grains, and bran. About £200 per annum is spent in

artificial feeding stuffs, while artificial manures are used to the

value of £100. As this is one of the best farms in the district, we have

ascertained approximately the cost per acre of the production of each

crop grown on the farm. It is as follows:—the rental in each case being

47s., and the rates and taxes 1s. 3d. per acre— Oats—seed, 20s.;

manures, 40s.; cultivation and harvesting, 40s.; labour (including

threshing and marketing), 10s.; and sundries (including tradesmen's

bills), 5s. Potatoes—seed, 60s.; manures, £10 ; cultivation, £7;

labour, &c, 40s.; sundries, 15s. Turnips—seed, 5s.; manures, £8 ;

cultivation, &c, £5 ; labour, &c, 20s.; sundries, 12s. Wheat—need,

25s.; cultivation, &c, 40s.; labour, &c, 10s.; sundries, 5s.

Glover Hay—seed, 20s.; manures, 10s.; cultivation, 10s.; labour, &c,

10s.; sundries, 5s. The average crops vary in quantity and value

according to circumstances. During the four years ending 1877 oats

yielded on average 7 quarters of grain, 240 imperial stones of straw per

acre, the value of the former being £8, 8s., and the latter £6. In the

same time wheat yielded 5 quarters of grain, and 240 stones of straw,

which sold at £11 and £7 respectively. In the year 1878 the return of

oats reached 7½ quarters, for which the tenant

realised £9. The yield of fodder was the same as before, but the price

had fallen to £4, 10s. Wheat was exactly the same as before in yield,

but £10 only was obtained for the grain; and the relatively smaller

price of £4, 10s. for the straw. The yield of oats in 1879 fell to 5½

quarters, which brought £6, 17s. 6d., straw being the same in weight and

value as in 1878. Wheat too suffered a reduction of fully a third both

in yield and value, except in straw, which maintained its previous

years' weight and value. Since then, better crops than those of the

disastrous year of 1879 have generally been raised, but the financial

return per acre has greatly diminished during

the past two or three years. Hay yields about 2 tons per acre, turnips

about 10 tons, and potatoes 4 tons. The prices of these commodities are

variable; but Mr Bowie gives the following as the average prices per ton

of a few years past:—hay, £3, 15s.; turnips, £1, 15s.; and potatoes, £7.

The productiveness of the farm has been improved since 1860 by draining,

while the farm buildings have been extended and repaired. The outlay in

draining was defrayed by the landlord, the tenant paying interest at the

rate of 6f per cent., while building operations and improvements were

mutually performed. The servants employed by Mr Bowie are engaged partly

by the year, by the week, and by the day, and the cost of labour

approaches £3 per acre—considerably less than it was some ten years ago.

Mr William Park, formerly tenant of Gallowhill, which

is also in the Abbey parish, gave the Royal Commission some useful

information regarding the farm of that name. It extends to 100 acres,

consists of medium soil, and was held by Mr Park on a fifteen years'

lease, which terminated in 1883. It was worked on the four-shift

rotation, and rented at £340, while the rates and taxes amounted to

about £20. The conditions of lease were closely enforced, which

restricted the tenant to a certain course of cropping. This he

considered a hindrance to profitable farming. He used artificial manure

on the farm to the value of about £100 yearly, while he expended a

similar sum in feeding stuffs. The cost per acre of the production of

crops was approximately thus:—Potatoes—seed, £4; manures, £14;