|

By Thomas Farrall, Aspatria,

Carlisle. [Premium—Ten Sovereigns.]

Introductory—Geography of

Ayrshire.

Seeing that the climate,

surface, soil, and geological formation have always a remarkable effect on

the cattle bred and reared in any district, it has been deemed desirable

to give a short geographical sketch of the county of Ayrshire, the home of

the Ayrshire breed of cattle.

The county lies in the

south-west part of Scotland, and forms a sort of natural basin. Owing to

its close proximity to the sea, the climate is somewhat moist, but far

from unhealthy. The rainfall is considerable, especially near the Isle of

Arran, where the clouds, being attracted by the lofty mountains,

oftentimes drop their moisture pretty copiously. The air is mild, not

being-subject to such extremes as in the east of Scotland ; nevertheless,

bitter storms from the Atlantic are sometimes experienced. Rivers are

numerous, their general direction being from east to west, but few of them

exceed thirty miles in length, many of them much less. The principal

are—the Ayr, the Doon, the Girvan, and the Stinchar. The geological

features of the county may be thus briefly defined:—Northward, from the

river Girvan, the Old Red Sandstone occurs frequently ; and on the south,

the Lower Silurian strata chiefly prevail. The upper or superficial soil

is varied, consisting of clay soil, light or sand soil, and about 300,000

acres of moss or moorland. The light or sandy soil skirts the entire

length of the coast, being interspersed with a deep and fertile loam. The

moorlands lie principally along the eastern boundary, and are intersected

with large mosses, the principal of which are Aird's Moss, and Moss-Mallock.

The latter lies partly in Lanark and Renfrew shires. In the parishes of

Muirkirk and New Cumnock, which are in the eastern part of the shire, more

than half the land is moss. By far the largest extent of the surface soil,

however, is of a clay character, which varies much in its quality; in some

parts it is strong and productive, while in others it is wet and cold,

producing a poor class of herbage, barely sufficient to keep alive a

breeding-stock, and totally unfit for fattening cattle. Notwithstanding

this, the county of Ayrshire occupies the second position in Scotland as

regards stock-breeding, being surpassed only by Aberdeen.

It may further be remarked that Ayrshire is

naturally divided into three separate districts, viz., Cunningham, which

embraces the whole of the surface from the river Irvine northwards to the

confines of the county ; Kyle, the central division, extending from Irvine

southwards to the Doon; and Carrick, which takes in the whole extent south

of the Doon. Cunningham is the district whence the improved breed of

Ayrshire dairy cattle have sprung into existence.

About three-sevenths of the entire area of

Ayrshire is in cultivation. Oats form the principal crop. A little wheat

is raised ; and large quantities of potatoes are grown on the light soils

along the coast. Turnips and clover are also produced in abundance. Nearly

one-half of the cultivated land is devoted to pasture, rather over

one-fourth to clover, upwards of one-sixth to oats, and the remainder to

miscellaneous crops.

History of the Breed.

Various theories have from time to time been

promulgated anent the origin of the Ayrshire breed of cattle. That it was

at the outset, in common with other breeds, descended from the wild

cattle, which in bygone days were to be found roaming at large throughout

Britain, admits not of a doubt; for it is well known that the various

circumstances of climate, soil, and so on, have a wonderful tendency to

change the form and appearance of any species, whether of cattle, sheep,

horses, or other animals.

In wild animals, a uniform figure and colour

are generally found to prevail, that is, when they have unrestricted

freedom; but confine them to any particular district, and they begin to

assume certain characteristics quite peculiar to themselves, not indeed to

individual animals, but to those under the same condition of

life—characteristics conformable to the district where they are confined.

The longer this sequestration continues, the more marked and better

defined will be the features of which it is the principal cause, until, in

the end, they become inseparable from the breed by which they are

possessed. On this point a reasonable question might be put— "Why this

sequestration or retirement?" It may be answered in the following manner.

Undomesticated animals often, quite of their own accord, attach themselves

to certain localities, which they and their offspring cling to for

successive generations with pertinacious tenacity. Herdwick sheep, for

example, originally chose for their heath the mountains of Cumberland and

Westmoreland, after having saved themselves from a stranded ship on the

shores of the Solway Firth, and have at length attained those

characterisms which fit them well for the position they have to occupy.

It therefore seems most probable that a few

descendants of the ancient British breed originally settled down in the

western part of Scotland; where in time their progeny acquired properties

quite in accordance with storm and tempest, upland moor and barren moss.

Many of the peculiarities they then possessed undoubtedly betokened

wonderful milking capacities, in the same way that several points of the

unimproved shorthorn indicated a tendency to early maturity, or that the

form and general appearance of the West Highlander denoted extreme

hardihood. In the

manner just described, it is believed that nature laid the foundation of

the most noted milking breed of the present day. The wily Scots-farmer

would probably soon find out the existence of this important quality, and

perhaps strive to improve it so far as his knowledge extended, or his

means permitted; but, in absence of authentic records bearing on the

point, it is impossible to show by what progressive steps the Ayrshire cow

was moulded into the form it possessed at the middle of last century; yet

it is reasonable to imagine that very little had been clone in the way of

selection or crossing with superior animals of the same type up to that

time; for Aiton, who wrote in 1825, describes the cattle, from his own

recollection, as having been a puny and unshapely race. The cows then gave

only 6 to 8 quarts of milk per day, and seldom exceeded 20 stones when

made fat, even in the height of the season.

So much for the supposed origin of the breed.

The records hearing on the improvement are much more reliable. Still, the

statements of writers are not unmixed with tradition, but so many facts

have been preserved from the pens of those who can be trusted, that it is

not a difficult matter to find connecting links in the history of the

Ayrshire, from the middle of last century until the present time.

The first mention of the Ayrshire breed of

cattle is supposed to be made by Ortelius, who wrote in 1573, when he says

that "in Carrick are oxen of large size, whose flesh is tender, and sweet,

and juicy." Compared with other native breeds, as the North Highlander,

the Ayrshire might then, as indeed it is now, be comparatively large. For

about 200 years after Ortelius wrote, little mention is made of the

Ayrshire, from which it may be inferred that the breed was not held in any

wonderful degree of esteem ; in fact, Culley, who wrote his treatise on

live stock towards the close of the 18th century, does not even mention

the Ayrshire as one of the recognised breeds of the country; and Fullarton,

in describing the county in which it was found, speaks of it in a manner

so general as to show that it was not regarded as anything remarkable.

Little progress, however, could be expected in

the breeding and rearing of cattle, when the agricultural condition of the

country is considered. The almost total neglect of land culture has been

ascribed to the religious feuds and dissensions which the inhabitants of

this part of Scotland passed through for a protracted period previous to

the year 1780, bringing upon them the usual concomitants of poverty,

misery, and squalor. Colonel Fullarton, in his survey of Ayrshire, says

that there were few good roads in the county; that the farm-houses were

miserable and dilapidated; that the land was foul with weeds, and that

there were no fallows, no green crops, no sown grasses, no carts nor

waggons, and no straw-yards. Milk and oatmeal, with a few greens, formed

the chief diet of the people, and the land was scourged with successive

crops of oats. Cattle were herded or tethered on the bare pastures in

summer, and in winter, so poor and meagre was their fare, that they were

scarcely able to rise in spring without assistance. Very little

agricultural improvement was effected until the close of the American War;

and much of what has been done is due to the pioneers of the present

century. So recently as 1811, in a report upon Ayrshire, the cattle were

described as being almost wholly black. That there was a certain

uniformity of colour may be gathered from the fact that provincial terms

were invented, having reference to the location of certain colours. Thus,

a cow marked with white towards the extremity of her tail was said to be

"tagged"; if a strip of white ran along the ridge of her back, she was

"rigged"; one with white on her neck was a "hawked" cow; a dark one with a

white face, a "bassened" cow; one with a profusion of white spots upon her

body, a "spotted" cow; and one with large patches of white, a "bawly,"

being a corruption of the term "piebald." The cattle in Cunningham were

described as being small in stature and badly fed; they were principally

black, gaily dotted with white spots; their horns were crooked and

irregular, and marked with ringlets near their base—a true criterion that

their "lines were not cast in pleasant places."

The improvement in the Ayrshire breed of

cattle dates from the year 1750, when, it is stated on competent

authority, that the Earl of Marchmont had brought from his estates in

Berwickshire a bull and several cows, which he had some time previously

procured from the Bishop of Durham, of the Teeswater breed, then known by

the name of the Dutch or Holstein breed. These cattle were of a light

brown colour, spotted with white. They were introduced into the district

of Kyle by Bruce Campbell, his lordship's factor, and rapidly getting into

repute, their progeny gradually spread into the adjoining districts. A

bull from this stock was eventually purchased, at what was considered a

very long price in those days, by a Mr John Hamilton, who raised a

numerous herd by crossing with the native cattle. Tradition asserts that

other proprietors brought to their farms foreign cows of the same breed,

and assuming this to be correct, it may readily be conceived that the

dispersion of the progeny would exercise a wonderful influence in

improving the native breeds. About the same time that these cattle were

introduced, Mr John Dunlop, of Dunlop House, in the Cunningham district,

purchased several stranger animals, from which the Cunningham cattle of

the present day are descended. The first crosses were obtained by coupling

bulls of the stranger with cows of the native race, but the offspring had

an ill-shaped, mongrel appearance, their bones being large and prominent;

yet in time these became toned down so much, that by continued care in

breeding, they at length possess all those well-defined features

considered so desirable in dairy cattle. In 1769, John Orr of Barrowsfield

bought in some stranger cattle, and his example is said to have been

copied by several other dairy farmers, but no mention of their names is

made. As to whether some of the cattle which were introduced into Dunlop

were Alderneys, as tradition asserts, there are no positive means of

determining, but the great similarity which exists between the Alderney

and modern Ayrshire would naturally lead to the conclusion that the blood

of the one has been largely mixed with that of the other. There is the

same peculiar character of the horns and colour of the skin; in fact, the

general resemblance is so great, that both Jersey and Alderney cattle are

occasionally mistaken for Ayrshires. A lecturer at an English farmer's

club meeting quite recently stated—on what authority he did not

mention—that "several Ayrshire farmers had introduced cows from the

Channel Islands, from all which, combined with West Highland blood, the

present improved breed of Ayrshires had arisen." An unknown writer in the

"Complete Grazier," the third edition of which was printed in 1808, says

that the Dunlop breed is the result of a cross between Alderney cows and

Ayrshire bulls. The horns of this race are small and awkwardly set. The

animals, it is further stated, are small in size, and of a pied or sandy

red colour. They are, notwithstanding, admirably calculated for the dairy,

on account of the richness and quality of their milk. Some people aver

that this is another account of the Dunlop importation, where the

Alderneys are accredited with the improvement, rather than the Dutch,

Teeswater, or Lincolns.

There is great uncertainty, and consequently

much diversity of opinion as to the early history of these crosses, but

weighing matters carefully over, and judging from the character which the

descendants still possess, it seems possible, nay, indeed, probable, that

the blood of both the Teeswater and Alderney types has been largely mixed

with that of the native stock. In support of the statement regarding the

introduction of Alderneys, it is asserted by Colonel de Conteur, that

Field-Marshal Conway, the Governor of Jersey, and Lieut-General Andrew

Gordon, who succeeded him, both sent about the close of the eighteenth

century some of the best cattle to England and Scotland. And Quayle, who

wrote an agricultural survey of Jersey, says that the Ayrshire is a cross

between the shorthorn and the Alderney. No doubt when he wrote the word

"shorthorn," he intended to convey a general meaning, pertaining to

shorthorn cattle as distinguished from longhorns, and not to the tribe now

known as the shorthorn breed.

On the other hand, Aiton, who wrote a survey of the county, and was

himself a farmer in the district of Cunningham, after diligent and careful

inquiry into the origin of the breed, was of opinion that they are

descended from the native cattle, changed in their colour and partly in

their shape, size, and qualities, by being crossed with the Teeswater or

Dutch breeds. Such are the opinions of early writers, and although their

accounts differ slightly in detail, they all agree in one point —that the

Ayrshire cattle are the result of a cross between the native type and some

foreign breed or breeds.

Although the improvement in Ayrshire cattle

dates from the year 1750, it cannot be said to have become anything like

universal until about the year 1780, when a much better system of farming

was adopted, more attention was devoted to the breeding and rearing of

stock, and a much more generous fare was substituted for that which was

barely necessary to sustain life. Higher rents were demanded, and these

served as a stimulus to industry; for, as the clay soil was in excess, and

liable to be poached if worked under the almost continual dripping of the

clouds, more attention was devoted to dairy farming than to the growth of

wheat or other cereals.

Thus the race of Ayrshires was ameliorated

step by step, until it has attained its present state of perfection. A

considerable time has elapsed since the improved breed was established in

every district of Ayrshire proper, as well as since its adoption in many

other counties. A Mr Fulton is said to have first planted it in Carrick

about the year 1790; while a Mr Ryan established the first herd in

Wigtownshire, on the south side of Lochryan, in the year 1802. Towards the

end of last century several cattle were introduced into Dumfriesshire,

having been brought to the estate of Mr Hope Johnstone of Annandale.

Altogether, dairy farming spread rapidly towards the close of last, and in

the beginning of the present, century, and in most of the south-western

counties of Scotland the Ayrshire breed is gradually supplanting others.

Some of the most noted dairy farmers and

breeders of stock in the county of Ayrshire are—Mr Andrew Allan, Munnoch,

Dairy, who has a dairy of about 75 cattle, and who bred the cow which took

first honours at the Highland Society's Show at Glasgow this year (1875);

Mr J. N. Fleming, Knockdon, Maybole, well known as a prize-taker, and

generally acknowledged to have the best Ayrshires in Scotland; Mr J.

Parker, Broomlands Kilmarnock; and Mr J. Howie, Burnhouses, Kilmarnock.

In the district lying around East Kilbride,

Lanarkshire, are also some noted herds. Particularly may be mentioned as

owners— Mr Thomas Ballantyne, Netherton; Mr John Hamilton, Skeoch; Mr

George Crawford, Bogside; and Mr William Craig, Crutherland,—all having

been prize winners for Ayrshire dairy cattle.

In Stirling, fine herds are owned by the

following:—Mr Duncan Keir, Bucklyvie; Mr W. A. M'Lauchlan, Auchentroig,

Balfron; and Mr Hugh Fleming, Ballaird, Balfron.

At Holestane, in Dumfries, His Grace the Duke

of Buccleuch has a fine herd of thirty years' standing. It consists of 40

cows with their followers—viz., 7 bulls, 24 queys rising three years old,

and 32 rising two years old. Surplus milk, formerly made into Cheddar

cheese, but now into Dunlop. Many of the animals are noted prize-winners.

It would serve no useful purpose to enter into

a long list of the names of breeders in each county; suffice it to say

that there are in most of them many pioneers, who are sparing neither

pains nor expense to bring the Ayrshire to the highest possible state of

perfection. It may be

mentioned that here and there a herd of Ayrshires has been planted on the

English side of the border. Mr Alexander M'Caw, of Greysouthen, near

Cockermouth, Cumberland, has a standing dairy of 100 Ayrshire cattle, the

produce of which is mostly made into cheese, for which there is great

demand, as cheese-making is a branch of husbandry very little understood

or practised by the north of England farmer.

Prices of young stock vary according to age

and quality, and milch cows range from L.12 or L.14 to L.18 or L.20. For

good bulls, high figures are occasionally given.

Points of Ayrshire Cattle.

The modern Ayrshire has well defined

characteristics, which are unmistakable by the observer when once

understood. The horns are small, wide apart at the base, have an upward

inclination and a graceful curve inwards. The head is small; the neck long

and fine where it joins the head, but gradually thickening to where it is

set upon the shoulders. The forequarters in general are thin, the body

developing gradually towards the hinder parts. The colour is brown, mixed

more or less with red, the markings being clearly defined; while the skin

is soft, pliant, and pleasingly elastic to the touch. The thighs are deep

and broad, and the legs short. The udder is large without being flaccid;

well developed without being cumbersome. Indeed, the general contour of

the Ayrshire betokens milking capacities of no mean order. There is very

little coarseness about the true breed, most of the points being what

connoisseurs call "good."

The most approved form of the best milkers is

thus described by Mr Aiton:—Head small, but rather long and narrow at the

muzzle; the eye small, but quick and lively; the horns small, clear,

bended, and the roots at a considerable distance from each other; neck

long and slender, and tapering towards the head, with little loose skin

hanging below; shoulders thin; forequarters light and thin; hindquarters

large and capacious; back straight, broad behind, and the joints and chine

rather loose and open; carcass deep, and the pelvis capacious and wide

over the hips; tail long and small; legs small and short, with firm

joints; udder capacious, broad, and square, stretching forwards, and

neither fleshy, low hung, nor loose, with the milk-veins large and

prominent; teats short, and at a considerable distance from each other;

the skin thin and loose; hair soft and woolly; the head, horns, and other

parts of least value small, and the general figure compact and well

proportioned. There is to the present day-much dispute with regard to the

origin of the Ayrshire cow.

The following description from a report to the

Ayrshire Agricultural Association gives the points which indicate superior

quality in the Ayrshire dairy cows:—

Head short, forehead wide, nose fine between

the muzzle and eyes, muzzle moderately large, eyes full and lively, horns

wide set on, inclining upwards, and curving slightly inwards.

Neck long and straight from the head to the

top of the shoulder, free from loose skin on the under side, fine at its

junction with the head, and the muscles symmetrically enlarging towards

the shoulders.

Shoulders thin at the top, brisket light, the whole forequarters thin in

front, and gradually increasing in depth and width backwards.

Back short and straight, spine well-defined,

especially at the shoulder, the short ribs arched, the body deep at the

flanks, and the milk-veins well developed.

Pelvis long, broad, and straight, hock-bones (ilium)

wide apart and not much overlaid with fat, thighs deep and broad, tail

long and slender and set on level with the back.

Milk-vessels capacious and extending well

forward, hinder part broad and firmly attached to the body, the sole or

under surface nearly level, the teats from two to two and a half inches in

length, equal in thickness, and hanging perpendicularly; their distance

apart at the sides should be equal to about one-third of the length of the

vessel, and across to about one-half of the breadth.

Legs short, the bones fine, and the joints

firm. Skin soft and

elastic, and covered with soft, close, woolly hair.

The colours preferred are brown, or brown and

white, the colours being distinctly defined.

Great value is attached to the above form and

points by the dairy farmer, and he quickly takes them in when effecting a

purchase, so that a mistake is rarely made. The following-ingenious

versification of the points of an Ayrshire cow are based on a document

published under the authority of the Ayrshire Agricultural Association:—

Would you know how to judge of a good Ayrshire

cow?

Attend to the lesson you'll hear from me now;

Her head should be short, and her muzzle good size;

Her nose should be fine between muzzle and eyes;

Her eyes full and lively ; forehead ample and wide;

Horns wide, looking up, and curved inwards beside;

Her neck should be a fine tapering wedge,

And free from loose skin on the undermost edge;

Should be fine where 'tis joined with the seat of the brain;

Strong and straight appear line without hollow or mane;

Shoulder-blades should be thin where they meet at the top;

Let her brisket be light, nor resemble a crop;

Her fore-part recede like the lash of a whip,

And strongly resemble the bow of a ship ;

Her back short and straight, with the spine well defined,

Especially where back, neck, and shoulders are joined ;

Her ribs short and arched, like the ribs of a barge;

Body deep at the flanks, and milk-veins full and large;

Pelvis long, broad, and straight, and in some measure flat;

Hock-bones wide apart and not bearing much fat;

Her thighs deep and broad, neither rounded nor flat;

Her tail long and fine and joined square with her back;

Milk-vessel capacious, and forward extending,

The hinder part broad and to body fast pending;

The sole of her udder should just form a plane,

And all the four teats equal thickness attain;

Their length not exceeding two inches or three;

They should hang to the earth perpendicularly;

Their distance apart, when they're viewed from behind,

Will include about half of the udder you'll find;

And when viewed from the side, they will have at each end

As much of the udder as 'tween them is penned;

Her legs should be short and bones fine and clean,

The points of the latter being quite firm and keen;

Skin soft and elastic as the cushions of air,

And covered all over with short woolly hair;

The colours preferred are confined to a few,

Either brown and white checkered or all brown will do;

The weight of the animal leaving the stall,

Should be about five hundred sinking offal.

Such are the points of the Ayrshire as they

were formerly considered, and the scale has changed little up to the

present day. The arrangement is judicious in most respects, all the points

being bestowed upon what may be termed the local indications of milk. The

dairyman seems thoroughly to understand the essential features which

betoken milk-giving propensities, caters for them, and fixes them

accordingly. Breeding,

Rearing, and General Management of Stock.

The Ayrshire dairy farmers are very particular

in the breeding of their cattle. In order to secure the milking-properties

as far as possible, they select a bull possessing so much of the feminine

aspect as pertains to the neck, head, and forequarters; having also

sufficient breadth between the hocks and fulness in the flanks. They

prefer that the scrotum be white; indeed, so much attention is paid to

this point, that many breeders would reject an animal if the part in

question were of any other colour. When a bull is selected from a herd,

other than that in which he is required to serve, great care is taken that

he be descended from a stock noted for its milking qualities, independent

of the virtues which he himself possesses. The purchaser satisfies himself

that the mother of the bull was a strong, profitable cow, for he knows

that the maternal parent of the sire has a most unmistakable influence

over the progeny for many generations. Indeed, the aim of the dairyman is

to cultivate a race of cattle noted alike for their harmony of colour,

beauty of contour, and fill-pail proclivities. Whatever is due to the

introduction of and crossing with foreign animals, and also to the

superior food which the cattle of the present day receive compared with

the meagre fare of last century, there can be no doubt that the world-wide

repute which the Ayrshire has at length gained as a milker is mostly owing

to the selection of animals for breeding purposes. In the female the

better milker is always retained, while the poorer is rejected, the

dairyman having great faith in the adage that "like produces like." Those

exterior outlines which experience shows exist in the better cows are

sought for in the younger cattle, and aimed at in the coupling. Thus, the

modern Ayrshire has, as it were, by degrees been built up, until she is a

milker of unsurpassed excellence, her form according with that which

indicates this faculty. Her udder has become developed in size, perfected

in shape, and extended to a wonderful degree of capacity ; her soft woolly

coat protects her body from the rough storms which now and then sweep

across the Atlantic; while her body is light before and heavy behind, for

the breeder knows that such characteristics are a sure guarantee of

milking capabilities. The advance has been gradual for almost a century,

each step having been fixed as it was gained. Her type is the type sought

for by dairy farmers, not only in Ayrshire, but in the adjoining counties

of Western Scotland as well—from the Grampian Mountains to the Solway

Firth and the Cheviot Hills. Neither is the neat, little, milk-giving

Ayrshire confined to its native country. It is sought after to crop the

verdant pastures of different parts of England; it graces many dairy farms

in Holland; it has crossed the wide Atlantic, and feeds along the northern

as well as the southern shores of the river St Lawrence, or rests beneath

the shadows of the Rocky Mountains. A reference to the prevailing-points

of six noted dairy breeds will suffice to show that the characteristics of

the Ayrshire stamp her as a dairy cow of a high order, viz., the Fifeshire,

as described by Magne; the Yorkshire, which is the unimproved shorthorn,

by Haxton; the Jersey, by Allen; the Suffolk, by Kirby; the Brittany, by

Gamgee; and the Ayrshire, by Aiton. The points which predominate are the

following:— Head,

long.

Muzzle, fine.

Throat, clear.

Neck, slender.

Shoulders, thin.

Chest, deep.

Brisket, small.

Back, straight.

Thighs, flat and thin.

Bibs, arched.

Pelvis, roomy.

Belly, large.

Legs, small and short.

Udder, large, square, and well-formed.

The management of Ayrshires varies slightly in

detail, owing to circumstances, but, as a rule, the dairy cattle calve in

March and the beginning of April. During the time that the cows are dry,

they are fed in the byre, chiefly on oat straw and turnips, until about a

month before calving, when their dietary is slightly improved. After

calving, they are fed upon hay with boiled turnips and chaff, mixed

together; or cut hay with bean-meal. Many adopt the practice of boiling

the turnips and chaff in the same cauldron for several hours, and then

adding a little bean or pea meal. This makes a nourishing diet, and one

which the cows eat with avidity. The mixture is given twice a-day, as much

sweet hay as the cows will eat up clean being supplied at other times

between the morning and evening meals. Cattle so fed produce large

quantities of rich, well-flavoured milk. The following is the mode of

feeding adopted during a milking competition of Ayrshire cows:—

One bushel draff, mangold, bean-meal, oatmeal,

and mangold juice with oatmeal. Mangold boiled, and bean-meal. Cut grass

with 2 lbs. bean-meal, 1 lb. oatmeal, 1 lb. bran, and ½ lb. oilcake.

Of course the above method of feeding is

entirely extra, the aim being to promote the secretion of milk as much as

possible, regardless of expense.

When the pastures contain a nice bite, which

in ordinary seasons is about the 12th of May, the cows are liberated from

the byres, and allowed to forage for themselves. In very hot weather, they

are kept in during the day, and supplied with cut grass, being turned into

the fields only at night. In moderately cool weather, soiling is

discontinued. During autumn, the cows are partly fed upon second clover

and partly upon turnips, the latter being thrown upon the pastures. In

October, the milch cattle are housed at night, receiving straw morning and

evening, and turnips by day. Up to the 1st of December, when the cows are

put dry, they get hay and roots,—potatoes or turnips,— after which their

fare is reduced to straw and turnips.

Comparatively few pure-bred Ayrshire steers

are reared for grazing, the male calves being usually sent to the butchers

when young. The heifer calves are supplied with milk for a period varying

from six to nine weeks, when they have sour milk or gruel for another

month. They are allowed to run upon an old-laid pasture till the month of

August, being then removed to the hay-foggage to get them up in condition,

as sudden thriving in calves is said to encourage "Black Spaul." They thus

retain their calf-flesh, and remain in good condition during the winter,

if liberally treated.

They are again sent to the moors the second

summer, and brought home to good grass in the autumn. They are then six

quarters old. When taken up, the young cattle are allowed a portion of hay

or mash with their straw and turnips. About February the in-calf heifers

are supplied with a little meal to make good the drain of nourishment

caused by the growth of the calf. It is considered dangerous, however, to

feed very heavily, until a little while after calving; then a more liberal

diet is given, and the young cow brought into full milk.

Here a point crops up which has provoked much

discussion in agricultural circles, viz., as to whether it is more

profitable to have heifers in profit when they are between two and three

years old, or a year later. It is generally conceded, and experience bears

the theory out, that cows between two and three years of age not only give

more milk during the first season than those of a more advanced age, but

that they continue better milkers in after years. The reason assigned for

this is, that they become in calf at a time more in accordance with the

promptings of nature, and that, therefore, the milk flows more copiously.

However, bringing cattle into profit so young is thought by some to be

hurtful in stunting the size, and preventing them from getting a desirable

amount of bone; while others, on the contrary, urge that the extra diet

which they receive when milking, develops them quite as much as running

free another summer upon a bare moor.

In some districts, dairy cattle are let out to

men called "bowers" for the season. These bowers either pay a fixed rent

for each cow in money, or deliver so much cheese at the end of the year,

as may be agreed upon. The farmer supplies pasture for the summer months,

and a regulated quantity of feeding-stuffs for the winter; the usual

allowance being five or six tons of swede and common turnips per cow, with

2½ cwt. of bean-meal, and hay and straw. The herd, with his family,

performs all the necessary labour in attending to and feeding the cattle,

as well as the making of cheese. The payment which the herd is called upon

to make depends much upon the quality of the pastures, the value of the

produce, &c, but the usual rates are L.11 to L.14 when paid in money, and

3 to 4 cwts. of cheese when paid in kind.

Produce of the Ayrshire.

Enough has already been advanced in favour of

the Ayrshire as a milker. It is a well-established fact that no breed of

cattle in the British islands will produce an equal quantity of milk,

butter, and cheese from a given amount of food with the purebred Ayrshire.

Of the precise yield of milk which a cow gives, it is difficult to speak

with any degree of certainty, so much depending upon the size, breeding,

and age of the animal; the quantity and quality of the food given, the

attention to milking, and regulation of the byre-work, together with many

other circumstances, having a certain amount of influence in determining

the quantities of milk given by individual cattle. Aiton, in his "Survey,"

says that some cows produce 5 to 6 gallons per day for a time. Long after

committing this statement to paper, he was led to believe that he had

underrated the quantity, as he was informed that many cattle yield 6 to 7

gallons per day for six or eight weeks ; but these, he remarks, are

extraordinary returns. Several, when in their best plight and well fed,

will yield 4 gallons per day for three months, and produce a total of 800

to 900 gallons per cow. As an average, 600 gallons per cow for the year

has been mentioned, but on the poorer farms the average yield falls far

short of this, and cannot be more than 480 or 500 gallons.

There are various methods of converting the

produce of the dairy into cash, dependent chiefly upon the extent of the

farm, the quality of the soil, the circumstances of the dairyman, and the

proximity, or otherwise, to a town. The owners of small dairies, if

possible, dispose of their produce as new milk in a neighbouring town; the

occupiers of the largest class of dairies generally go in for

cheese-making; while the produce of medium-sized dairies is sold as milk,

converted into butter, or made into cheese; sometimes a combination of two

or more of the above methods is observed, as circumstances render

desirable. The

following details show the comparative advantages of each system, as well

as the actual amount of produce obtained on several dairy farms, names

being withheld by desire.

No. 1 is a dairy of 10 cows. The milk is

disposed of daily at 10d. per gallon. The average for 250 days was last

year 2½ gallons per cow, giving a yearly total of 625 gallons for each.

Value of whole produce for the year, L.26, 0s. 10d. About L.4 per head

spent in artificial food.

No. 2 is a dairy of 16 cows. Average for 240

days, 9 quarts per cow daily. Value of produce, L.22, 10s. A little over

L.3 spent on extra food.

No. 3, dairy of 24 cows. Milk made into

butter. Average per cow throughout season, nearly 5½ lbs. per week, or an

aggregate of 220 lbs. per cow. This, calculated at 1s. 3d. per lb., with

L.3, 10s. for milk, brings the amount per cow up to L.17, 5s. Cash spent

on food, about L.2, 15s. per head.

No. 4, dairy of 14 cows. Milk also made into

butter. Average, 240 lbs. for year. This, estimated at 1s. 4d. per lb., as

advised, makes L.16. Butter-milk valued at L.4, making the total sum L.20.

Feeding substances purchased in, L.3, 4s. 8d. per cow.

No. 5, dairy of 75 cows. Produce made into

Cheddar cheese. 4 cwt. average per cow. Sold at 70s. per cwt., or a total

per cow of L.14. No estimate of milk or whey given.

Where the milk can be disposed of daily as

obtained, the returns are the largest; but such farms are said to be

privileged, and rents are consequently higher.

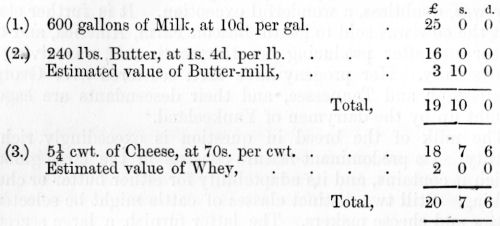

For the sake of comparing the three methods of

disposal, an example may be adduced. In the suppositious conversion of

milk into butter and cheese, the usual recognised standard is observed,

viz., 2½ gallons of milk to 1 lb. of butter, and 1 gallon to 1 lb. of

cheese, although some dairymen now calculate 30 gallons of milk to 24 lbs.

of cheese. Say an average dairy cow, with moderately liberal diet, yields

600 gallons of milk per annum, the following results are obtained:—

It appears that of the three systems, the sale

of the produce in the shape of milk is most profitable; that cheese-making

stands second, and butter last. Of course, the prices current for the

different articles would render the returns variable, but it is usually

understood that milk selling is the most advantageous where there is

sufficient off-gate for the produce, inasmuch as milk is an exceedingly

perishable article, and cannot easily be conveyed long distances, so that

competition is to a certain extent prohibited.

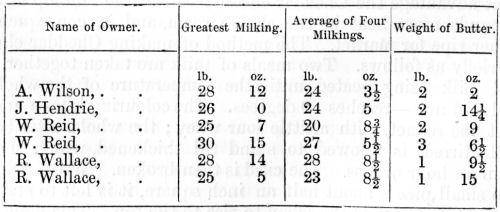

The following figures show the result of a

milking competition held at Ayr on the 26th and 27th days of April 1861,

viz.:—

In the above competition, the greatest yield

at a single milking was rather over 3 gallons, which produced at the rate

of 15 lbs. of butter per week. But being a competition, and the cows

highly fed, the returns afford no fair criterion of the ordinary milking

capacities of an Ayrshire cow.

At a milking competition in Holland, held in

the year 1872, three Ayrshires gave 5386 quarts during the season, being

an average of 1795 1/3 each, or 4 92/100 quarts per day for the whole

year. The rich grasses of Holland, however, tend to make the cattle

produce fat rather than milk.

It is said that an Ayrshire cow, bred by Mr

Finley of Monk-land, near Glasgow, gave 36 quarts daily for six months.

This, reckoned at one shilling per imperial gallon, amounts to L. 81. The

cow was, doubtless, a wonderful exception. It is further stated that the

cow was sold to go to Beacon Farm, America, and that a year ago, after

producing her thirteenth calf, was giving 23 quarts daily. Her progeny

have been scattered over Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee, and their

descendants are eagerly bought up by the dairymen of Yankeeland.

The milk of the breed in question is

exceedingly rich in quality. Its predominant feature consists in the large

globules which it contains, and its adaptability for either butter or

cheese making. Still two distinct classes of cattle might be selected—

butter and cheese makers. The latter furnish a large secretion of milk,

containing a smaller globule, and more numerous granules than does the

milk from the butter family. Many cattle possess both the butter and

cheese making faculties in a remarkable degree.

The Making of Cheese.

The limited space at

command in this paper precludes the possibility of entering into a

lengthened dissertation on cheese-making; it, however, may be stated that

there are two systems— the time-honoured Dunlop, and the Cheddar system,

each of which has its zealous advocates. The latter has gained

considerable ground of late years, especially in large dairies. One great

advantage the Cheddar cheese has over the Dunlop is, that it stands more

heat in the cheese room, and is, consequently, sooner ripe for market. The

method of making Cheddar cheese is briefly as follows. Two meals of milk

are taken together, the cold milk being heated until the temperature of

the whole— cold and new—reaches 90 degrees. The colouring is then added,

next the rennet, with a little sour whey; the whole, after being-well

stirred, is allowed to stand till thickened, which should be in an hour or

less. The curd is then broken. When reduced into small pieces about half

an inch square, it is left to stand a little while to allow the whey to

rise to the top. This done, the whey is taken off and heated to 150

degrees. Meantime the curd is broken quite as small as the grains of

wheat. When the whey is heated it is again put on, thus raising the

temperature of the curd to about 80 degrees in summer and 88 in winter,

twenty minutes being allowed for the mass to settle. The whey is taken off

a second time, heated and put on, thus raising the temperature to 100 deg.

in warm, and 105 in cold weather. The curd is once more allowed to settle,

and the whey finally poured off. The curd is then laid out to cool, after

which it is put in the press for a little while, taken out, milled and

salted—1 lb. of salt being used to 56 lbs. of curd. The substance is then

put into the press-vat at a temperature of 66 to 68 deg., great care being

taken to obtain the proper heat; for, if too warm, a portion of the fat is

sent off, and if too cold, all the whey and acid will not be separated

from the curd. On the fourth day, the cheese may be taken from the press,

neatly bandaged, and put into the cheese-room, which should be well

ventilated and furnished with a stove.

Feeding Qualities of the Ayrshire and its

Crosses. Although the

Ayrshire cow is bred chiefly for milking purposes, she also fattens very

quickly when put dry, for the same functions which ordinarily fill the

udder, also cover the frame with fat. Cows are fed off at various ages. If

any decline in milking qualities is noticed, some are fed off at seven

years, others are kept until nine, while extraordinary pail cattle are

sometimes kept until they are advanced in their teens. It is astonishing

how rapidly those aged cattle thrive when put upon a nice sweet pasture,

the herbage of which is somewhat richer than that to which they have been

accustomed. The Americans have also found out this quality which the breed

possesses. One farmer, whose dairy stock is entirely composed of Ayrshires,

says, "The Ayrshires are hardy and thrifty, are easily fattened and make

good beef, while for milking, in our country, are infinitely better than

any breed I have ever seen. They will fatten where a Durham cow would keep

as poor as a rail, and I have known them to furnish from 500 to 600 lbs.

of dressed meat. There are no better feeders, and their flesh is as fine

as anybody wants. In colour and shape I consider the Ayrshire as

attractive as most breeds, not much inferior to the Shorthorn, and vastly

superior to the fancy Alderneys, which are so difficult to get into

butchers' condition."

When crossed with a shorthorn, the progeny are

excellent types for grazing; they lay flesh on quickly and make heavy

weights. Many dairy farmers either keep, or have access to a Shorthorn

bull, using their favourite milkers for breeding Ayrshires solely for

dairy purposes, and the remainder of the stock for breeding shorthorn

crosses for grazing. Galloway crosses also thrive well; they are "kindly

doers;" they lay on a maximum amount of flesh with a minimum amount of

food, and are therefore in great repute in many districts. Indeed, the

•majority of practical graziers north of the Tweed are of opinion that the

Galloway-Ayrshire cannot be surpassed as a grazing description. The male

is generally on the Galloway side. The descendants have the reputation of

arriving early at maturity, fattening on what may be termed second-rate

pastures, and making highly profitable weights. On many high-lying farms

the cows are crossed with a Galloway bull; the produce reared on the farm

and sold off to graziers, or made fat at two to two and a half years old,

making from 13 to 14 stones per quarter. The Galloway crosses are best

adapted for the high moors, being of a hardy character; the shorthorn

crosses for the Lowlands, where the climate is more genial, and the

herbage of better quality.

Conservation and Improvement.

Notwithstanding that many even noted dairy

farmers are opposed to pedigrees other than such as the cattle "carry

along with them," yet it is evident that a herd-book containing a faithful

record of how each notable animal was descended, would not only enhance

its value considerably, but would furnish a guide which would be

invaluable to Ayrshire purchasers. Moreover, it would serve as a sort of

history to the future generation of breeders, while its perusal would be a

source of gratification to every admirer of this wonderful milk-producing

race. Such a book the Americans have already published, a fact which shows

clearly in what great esteem the Ayrshire is held over the Atlantic. High

prices are now and then given for cattle which have distinguished

themselves at shows, as far as L.50 to L.60 having been paid for a single

animal for exportation. Some of the most noted breeders often sell animals

at long prices to be retained at home, but the caterers for export

purposes generally out-bid the local dairy farmers.

Judicious feeding and careful management also

tend to bring out the essential characteristics of the type; but it should

always be borne in mind that there is a limit even to liberal or generous

treatment, as pampered cattle succeed for a time only, if at all. It may

be further stated that nature undoubtedly designed the Ayrshire cow to be

the creature of a certain locality, to which she has in the course of time

become thoroughly acclimatised, and is now admirably adapted to all the

varied surroundings. Remove her to a colder climate and a more barren

soil, where the fare falls short of that produced by her native land, and

she soon shows symptoms of decline; transport her to a more genial climate

where the herbage is luxuriant, and her milking properties give way, while

her fattening qualities are more prominently developed.

In order, then, to retain all the excellent

points and propensities which the Ayrshires possess, and also to improve

upon them as much as is consistent with the laws of nature, care in

selection, care in rearing, care in feeding, and care in preserving a true

record of all animals that excel, are points worthy of observation;

avoiding, at the same time, extremes in over-feeding or pampering,

too-fine crossing, and transporting to climes and pastures unsuited to the

race. The above are,

in the opinion of many enlightened dairy farmers, some of the measures

which might be adopted, keeping in view the conservation and improvement

of the Ayrshire breed of cattle. |