who had received in dowry

the lands of, Deloraine and others in the Ettrick Forest. He was

subsequently appointed custos of the royal hunting seat of Newark, and

overseer of the Royal Forests, and acquired the lands of Philiphaugh and

the forest steadings of Harehead, Hanging-shaw, and Lewinshope. His

grandson John attempted to hold Newark against the king; but finding the

Royal forces arrayed against him, he surrendered his possessions to the

king, who sometime afterwards created him hereditary sheriff of the

Forest. Philiphaugh and Harehead, it may be mentioned, are still in the

hands of the descendants of the outlaw. The Battle of Philiphaugh

occurred at the junction of the Yarrow and Ettrick in 1645, in which the

Covenanters, commanded by General Leslie, defeated the forces of Charles

I. under the command of the Marquis of Montrose. Those of the fugitives

who retreated up the Yarrow were shot at the command of General Leslie;

and it is said that Montrose and a few of his troops fled over Minch

Moor, and never drew a bridle until they reached Traquair, a distance of

11 miles. Towards the latter end of the eighteenth century, Selkirkshire

produced two of Scotland's most celebrated sons. James Hogg, better

known as the "Ettrick Shepherd," and Mungo Park, the renowned African

traveller, were born in successive years, the former in 1770 and the

latter in 1771. Their birth-places still and will long remain objects of

interest to visitors, and centres of pride for the native inhabitants.

The building in which Hogg first saw the light of day has been

demolished, but Mungo Park's birth cottage is still wonderfully well

preserved.

The only towns in the county are Selkirk and part of

Galashiels. The former is a royal burgh, and along with Hawick and

Galashiels returns one member to Parliament. It is pleasantly situated

on an eminence rising from 400 to 619 feet above sea-level, but until a

comparatively recent date it presented a dull and decaying appearance,

being chiefly inhabited by an indolent class of people known as "The

Souters of Selkirk." During the past quarter of a century, however, it

has become an important manufacturing town, and a large proportion of

its inhabitants are now employed as mill-workers. The principal features

of interest in the town are monuments erected to the memory of Sir

Walter Scott, who was at one time sheriff of the county,

and to Mungo Park. The population of the burgh in 1871 was 4640, and in

1881, 6090; while its valuation in 1851 was £9904; in 1876, £15,433; and

in 1885, £22,898. Its parliamentary

constituency is 900. Galashiels is divided by the Gala into two parts,

the one section being in Selkirkshire and the other in the county of

Roxburgh. For police and judicial purposes, however, the whole town is

in the sheriffdom of Selkirkshire. Probably no other town in Scotland

has increased so rapidly in size as Galashiels. The population of the

town and parish inclusive, was only 780 in the year 1790 ; whereas the

population of the burgh alone had risen to 12,435 in 1881, 2756 more

than in 1871. Of the entire population 9140 inhabit the Selkirkshire

division. The first factory was erected in 1794, and there are now

upwards of twenty in the town devoted to the manufacture of tweeds,

plaids, shawls, blankets, yarns, &c. Galashiels was one of the first

towns in Scotland to adopt the Free Libraries Act. Though somewhat

irregular in form, it has much improved in appearance of recent years.

Its latest, and probably most adorning feature, is a new parish church

surmounted by a tower, which for sculptural design and beauty is not

surpassed by almost any other in the country. A plentiful supply of

water was introduced into the town in 1878, at a cost of £50,000. The

valuation of Galashiels in 1868 was £25,720; in 1879, £51,651 (including

railways) ; and in 1885, £59,751 (including railways) ; and its present

parliamentary constituency is 1865.

The villages and hamlets worthy of mention in the

county are Clovenfords, part of Deanburnhaugh, Ettrick Bridge, Yarrow-Feus

and Yarrow-Ford. The rapid development of these towns is largely due to

the excellent railway communication which they have for many years

enjoyed. The North British Railway from Edinburgh to Carlisle skirts the

northeastern boundary of Selkirkshire for a distance of about five

miles, with stations within the county at Bowland and Galashiels. A

branch line 6 miles in length connects the Galashiels and Selkirk, and

another branch runs up Tweedside to Innerleithen and Peebles, its

Selkirkshire stations being Clovenford and Thornilee. No fewer than nine

trains run daily between Edinburgh and Galashiels, and six between

Edinburgh and Selkirk.

Three important rivers flow through the county, viz.,

the Tweed, the Ettrick, and the Yarrow ; while the Gala forms its

eastern boundary for nearly five miles—from near Bowland to its junction

with the Tweed. The Tweed, which is the principal river, and has a

complete course of some 103 miles, flows for a distance of 10 miles

across the northern part of Selkirkshire— from its confluence with the

Gatehope Burn to its junction with the Gala. It divides the Selkirkshire

portion of Stow and Innerleithen parishes and Galashiels parish from the

parishes of Yarrow and Selkirk. Its tributaries are numerous ; it

receives in Selkirkshire seven streams on the right and three on the

left. The Ettrick and Yarrow flow diagonally through the county from

south-west to north-east in parallel courses until they join at

Carterhaugh, about a couple of miles above Selkirk, after which the

river is named the Ettrick Water. The Yarrow which rises in the borders

of Dumfriesshire, in its course of 25 miles, passes through the Loch of

the Lowes and St Mary's Loch, and receives nearly forty rivulets. The

Ettrick has its source on Capel Fell, and after a run of 32| miles flows

into the Tweed below Sunderland Hall. It has eight affluents on the left

bank and seven on the right. Next in importance is the Ale Water, which

rises in Roberton parish, and flows through Alemoor Loch into

Roxburghshire. The Tweed affords good salmon fishing, while the smaller

rivers and burns are productive of very good trout.

Lochs, though numerous, are of little importance. St

Marys, measuring 3 miles long and less than one mile in width, is the

principal sheet of water. It is famous for the loveliness of its

situation. It is embosomed by beautifully rounded green hills, which are

splendidly mirrored in its peaceful water. Who has not read of the "Lone

Saint Mary's silent lake"? It has been celebrated in verse by

Wordsworth, Scott, and Hogg. A narrow strip separates St Mary's Loch

from the Loch of the Lowes, which is one mile long and a quarter mile

broad. Like its larger sister, this lake is famed for its stillness and

the pastoral beauty of the surrounding scenery. At the northern end of

the strip dividing the two lakes stands a monument to the immortal

Ettrick Shepherd. Alemoor Loch is an expansion of the River Ale,

measuring about two miles in circumference. In the same district there

are several small lakes, some of which at one time afforded large

supplies of marl for agricultural purposes. The chief of these are

Hellmoor Loch, Kingside Loch, Crooked Loch, Shaws Lochs, and Akermoor

Loch. The Haining Loch, until lately, supplied water for the town of

Selkirk.

Adorned with so many beautiful streams and lochs and

precipitous hills, and inseparably associated as it has been with poets

of such renown as Wordsworth, Scott, and Hogg, we are not surprised at

Selkirkshire being dubbed the "cradle of pastoral poetry." It would be

difficult to find a more lovely scene than parts of the county presents

when viewed from certain standpoints. From the centre of Yair Bridge,

for instance, one of the prettiest scenic sights in Scotland is

obtained, and one that would baffle the most imaginative artist to

exaggerate. And there are other parts of the Tweed valley almost equally

well-wooded and varied, while the Ettrick and Yarrow rivers have each

been extolled in verse and song for their surpassing beauty. Indeed, no

stream has listened to so many songs in its praise as the Yarrow. "The

Ettrick," says a writer, "in the poetry of James Hogg and Henry Scott

Riddell, possesses songs worthy of the minstrels whose lays, so fondly

preserved in tradition by the natives of Ettrick, were saved from all

risk of oblivion by the labours of Scott and Leyden." The Gala Water

also shared largely in the poetic laudation of the last century. Sir

Walter Scott resided at Ashiestiel, in the Vale of the Tweed, before he

removed to Abbotsford, and there he composed some of his finest poems.

The chief seats in the county are Bowhill (Duke of

Buccleuch), Broad Meadows, Elibank Cottage (Lord Elibank), Gala House,

Glenmayne, Haining, Hangingshaw, Harewoodglen, Holylee, Laidlawstiel

(Lord and Lady Reay), Philiphaugh, Sunderland Hall, Thirlestane (Lord

Napier and Ettrick), Torwoodlee, and Yair.

The topographical appearance of the county is

somewhat rare. Viewed from a commanding height, it seems crowded with

hills and destitute of human habitations. It is largely cultivated in

the lower district, however, while almost every valley and glen is more

or less populous. Along the valleys in the higher parts arable farming

is also carried on to a considerable extent, but all above the town of

Selkirk is essentially a pastoral district. In fact, the whole county

may be described as such— for sheep breeding and feeding is the

rent-paying industry all over; but between Selkirk and Galashiels, and

along the Water of Caddow, a large breadth of the hill sides has from

time to time been brought under the plough; and, as shall subsequently

be shown, much sterile heath has been converted into crop-growing soil

within the past twenty-five or thirty years. Cultivation has been

gradually creeping up the hill sides in some parts of the upper as well

as the lower districts, but of late years the tendency has been in the

opposite direction. Arable farming has been found unprofitable, and the

farmers, who are generally industrious and intelligent, are to some

extent abandoning crop growing; my remarks on this subject shall be

reserved, however, for a subsequent chapter. The climate is variable,

but generally healthy, and favourable to agriculture. The soil varies

from stiff clay resting on retentive till to dry sandy soil

superincumbent on a subsoil of gravel. The prevailing rocks consist of

the Lower Silurian formation. On the tops of some of the hills and on

the moors of the south-western division of the county marshy spots are

to be seen.

There has not been much land put under wood within

the past twenty or thirty years, but in the earlier part of the century

a considerable breadth was planted. Hogg tells us that the late Duke

Charles of Buccleuch. planted liberally, but confined his operations too

exclusively to the vicinity of Bowhill, his favourite residence. The

same informant, writing in 1832, says "the present Lord Napier no sooner

came home to reside in Ettrick than he began planting with a liberal

hand, and that too in the upper parts of the district, where wood was

wanted. It is truly astonishing what his efforts have effected in so

short a time. The fine old woods of Hangingshaw have likewise been well

flanked with young ones by Johnstone of Alva. Boyd of Broad Meadows has

done his part adjoining there; so have all the Pringles on their lands

of very ancient inheritance in the eastern parts of the county." In 1871

there were 2973 acres covered by wood, and these figures were returned

unaltered in 1878; but there are now 3228 acres under plantation.

Besides these, one acre is under fruit trees, 6 acres used by market

gardeners for growth of vegetables, and one acre used by nurserymen for

the growth of trees and shrubs.

Extensive vineries, successfully managed for many

years by the owner Mr William Thomson at Clovenfords, deserve to be

mentioned as one of the industrial institutions of the' county. The

average yield of grapes, which are chiefly consigned to the London

market, is about 7 tons per annum.

Population.—The inhabitants of the county have

greatly increased in number every decade since the first of the present

century. This fact is borne out by the following statistics :— In 1801,

5388; 1811, 5889; 1821, 6637; 1831, 6838; 1841, 7990; 1851, 9809; 1861,

10,449; 1871, 14,005; and 1881, 25,564.

Increase since 1801, 20,176. It will be seen the rise was pretty gradual

previous to 1841, and that after that year the population increased by

leaps and bounds. This circumstance is due in a large measure to great

development of various industries pursued in the county during the past

forty years. The strictly rural portion of the population has not

multiplied so quickly nor so substantially as the inhabitants of towns,

whose chief employment is mill-work. During last century there was no

great increase or fluctuation in the number of people, as is shown by

the fact that in 1755 there were only 4622 inhabitants, as compared with

4646 in 1793. In point of population, Selkirkshire ranks thirteenth

among other Scottish counties, there being on an average 99 inhabitants

to the square mile. Of the 25,564 people enumerated in 1881, 13,405 were

females, and 11 Gaelic-speaking. The number of houses occupied in that

year was 5082, while 264 were vacant and 86 in the course of erection.

The parliamentary constituency of the county for the present year (1885)

is 306.

Climate.—The climate, as might be expected from

the extremely irregular surface of the county, is singularly variable.

While clear and healthy atmosphere prevails in the lower portions, cold

ungenial mists frequently enshroud the hills. But this circumstance is

not peculiar to Selkirkshire. The climatic conditions of several other

counties in Scotland are almost equally variable. It is well known that

moors and lofty hills attract mists and rains, but nowhere perhaps is

this fact more clearly illustrated than in Selkirkshire. In summer more

rain visits the higher altitudes of the western than the vales of the

eastern division, which is due to the clouds being largely robbed of

their superabundant moisture in crossing the hills. It is this fact,

together with the extreme elevation of the higher districts, that

renders them less suitable for cultivation than the lower parts, and

which intensifies the severity of the winter season. In winter,

snowstorms are frequent there, and sometimes snow lies in deep ravines

among the hills till far through the spring; while in the lower parts of

the county winter is less rigorous, and the air is generally salubrious

and pure. The cold vapours, so common in the upper districts, are often

injurious to vegetation in spring, as well as to the maturing of crops

in autumn, but in dry scorching seasons they have a very different

effect. It is unfortunate, however, for the upland farmer, that in the

majority of years his crops are retarded from ripening until harvest is

practically over in the lower regions, and that he should nevertheless

be the first to feel the iron grasp of winter. Meteorologically, winter

sets in considerably earlier in the more mountainous parts than in the

less elevated districts, and hill stocks, hardy though they be,

sometimes require to have their food supplies augmented with hay or

turnips, or to be removed to other quarters, while the flocks on the

lower ground are faring moderately well on the pasture. Harvest

operations are usually a full week earlier in the lower than in the

upper district, and crops are generally more satisfactorily secured; but

of recent years harvest operations all over the county have been a

little later than formerly.

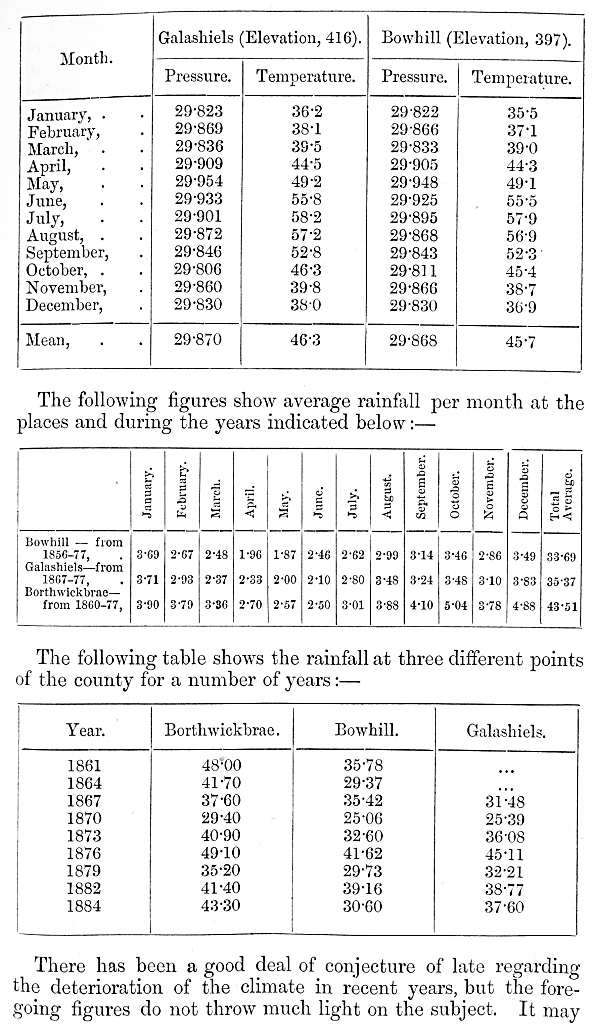

Through the kindness of Mr Buchan, Secretary of the

Scottish Meteorological Society, we are enabled to give some very

interesting figures showing in inches the pressure, temperature, and

rainfall registered by careful observers at various places in the county

during the past twenty-five years. The first statement shows the mean

monthly and annual atmospheric pressure at Galashiels from 1867 to 1876,

10 years; and at Bowhill from 1857 to 1880, 24 years; and the

temperature at the former from 1869 to 1880, 11 years; and at the latter

from 1857 to 1880, 24 years, thus:—

be interesting, however, to hear what one of the most

careful and experienced weather observers in the county has to say on

the point. He says:—"Some of our most experienced farmers are of opinion

that, in spite of the enormous sums spent on manures of all sorts, and

improved implements for every purpose, the land of Great Britain, acre

for acre, does not produce anything like the crops it did forty years

ago. If this statement is well founded, it is difficult to disconnect it

from climatal causes: thus the climate may be found to be almost the

sole cause of the severe depression under which agriculture is at

present suffering; and it is pleasant to think that this greatest of all

interests is certain to revive to its wonted prosperity when the weather

pendulum makes its return swing, as many expect, and we all hope, it

will ere long. Nothing could be more disastrous for this country than

that the weather should deteriorate by a few degrees."

Geology—Soil.

Regarding the geology of Selkirkshire there is not

much to be said. It affords little scope for research. Perhaps no other

Scottish county is less varied geologically. Its stratified rocks belong

almost exclusively to the Silurian formation. Large quantities of shale

and flags are embedded in the strata, but there is really nothing of a

geological nature deserving special notice. This chapter shall therefore

be devoted chieflv to a description of the soil, which to the practical

mind is infinitely more important than a harangue on technical geology.

The arable land, bearing the proportion of about one-eighth of the

entire acreage, unlike the geology of the county, is greatly

diversified, and varies in quality according to its situation. Much of

the more recently reclaimed land in the lower districts consists of

retentive clay, in most cases resting on a hard tilly subsoil. This

necessitates more extensive draining than is required on higher land,

and after all, the soil is difficult to fertilise and to keep in heart.

The soils of the haughs by the side of the river is in many cases light

but not unfertile loam, composed of particles of earth washed down from

the hills and high grounds in time of floods, and lying upon a subsoil

of gravel and sand. The quality of the upper stratum of such land is

observed to depend much upon that of the hills and higher grounds

through which the streams pass before they reach these haughs, and upon

the slowness and quickness of the current, as, according to these, the

sediment which they deposit must be more or less rich and fertile. Near

the sources of the streams the soil becomes more gravelly and less

productive, being better adapted for pasture than tillage. There are

spots of deep useful loam

to be met with apart from water deposits in the

middle districts of the county, and these are most numerous on southern

exposures. Soils skirting the hills are generally dry and friable. Moss

land seldom occurs, but on hills overrun with heath it is sometimes

observed. On the sides of hills productive of rushes and coarse grasses

clay soils predominate. In short, the land of the whole county may be

said to consist of clay and thin gravelly soil, with occasional

interlays of fertile loam and unproductive till. One of its most

remarkable features, especially in the lower districts, is the

multiplicity of small stones which it contains. It is surprising to see

land so largely intermixed with these subjected to regular rotation of

cropping, and yielding so well as it does. It is frequently observed

that moderately stony land is more productive than land from which the

stones have been removed, but a superabundance of stones tends to hinder

rather than help cultivation. Why moderately stony land should have

excelled in productiveness, seems to have been a partial mystery to the

farmers and agricultural writers of a century ago, but it is obvious to

all who have studied the subject that stones exert a mechanical

influence on the soil. They favour the admission of air to prepare plant

food, help the soil to imbibe ammonia from the atmosphere, and thus

increase its friability and capillary attraction. Fairly good crops of

the ordinary cereals—excepting wheat and rye, which are seldom grown—are

raised even in the higher districts of the county; while in a good year,

several low-lying farms produce equally as good grain and green crop,

both in respect of quantity and quality, as almost any other county in

Scotland. Considering the steepness and undulating character of the

land, it cannot be said that the soil generally is difficult to work. A

hundred acres is a common allotment to a pair of good draught horses in

the lower districts, but this is chiefly owing to the system of farming

adopted, and the tendency to diminish cropping and increase the extent

of permanent grass.

State of Agriculture prior to 1860.

All things are judged by comparison. Let us therefore

briefly glance back upon the state of the agriculture of the county

prior to 1860, in order to see as clearly as possible the progress of

the past twenty-five years. It is needless to go back much further than

the advent of the present century; we only require to go beyond that

limit some thirty years to prove that the county has undergone a great

revolution. About the corresponding period of the eighteenth century,

the soil was in a much less productive state than it was either at the

first of the present century or it is now. Between 1780 and 1800 the

spirit of improvement developed, and from a better knowledge of the

effects of manure and more extensive use of shell marl, farmers put, as

it were, a new face upon their land. Before the introduction of turnip

husbandry and summer fallow, farms were commonly under three divisions,

viz., "croft," "outfield," and "pasture." The best land or croft was

regularly tilled. It received all the dung made on the farm, and raised

alternate crops of beans, pease, and oats. Very little, if any of it,

was laid down with grass seeds. Except by folding the cattle, the

"out-held" was seldom if ever dunged, and it was exhausted by repeated

crops of oats, after which it produced little or no grass for a year or

two, and lay in lea until nature to some extent restored it. So soon as

it sent forth a fresh sward, it was again subjected to the same

treatment; and so on. The cattle were folded on it by "feal" dike

enclosures during night, and their manure mixed with the "feal" was

spread on the portion to be tilled. This was followed by two fairly good

crops, but the subsequent two were as poor as ever. As regards natural

pasture grounds, there was not so much change until within forty or

fifty years of the present day, but of course sheep and cattle, though

hardier, were much inferior in quality and size to those reared in more

modern times. Except around county gentlemen's residences and farms,

there was little fencing erected prior to the first of the present

century, and what was consisted of stone and earth—a dike of stones

surmounted with a row or two of "feal" or sod. Draining as a rule was

much needed and neglected, still a good deal of swampy ground was

improved, both by open and narrow close drains, from 2 to 3 feet deep.

The latter were filled with small stones below, and covered with straw

or bent and earth above. Small open drains were executed for three

farthings per rood of six yards, and one extensive farmer in the county

made upwards of 8000 roods of them on his holding prior to 1800. Lime,

in consequence of its distance from the principal part of the county,

was little used; but there having been lime works at Mid-dleton, about

23½ miles from Selkirk, the northern part of

the shire was better limed than the southern. It was generally applied

to land under summer fallow or lea, and then ploughed down. From 30 to

50 bolls was the usual allowance per Scotch acre. The staple manure of

the county at this early period was marl, which cost 7d. per cart-load

of 2 bolls. From 50 to 60 bolls were considered an adequate supply per

English acre for the lighter soils, but the heavier land got as many as

80 bolls. In the northern part of the county dung-mixture, composed of

dung, earth, and lime in alternate layers, was extensively used. Towards

the close of last century a great improvement was effected in the system

of cropping. Farmers became alive to the importance of alternating the

crops in order to avoid exhausting their soils. On the best soil the

rotation was—(l) turnips and potatoes with dung, (2) barley with grass

seeds, (3) hay, (4) pasture, (5) oats. Another system was—(1) turnips

and potatoes dunged, (2) barley with grass seeds, (3) hay, (4) hay, (5)

oats, (6) pease, (7) oats following turnips. A small quantity of wheat

was grown on the strongest soil and warmest situation. Barley was sown

on the best land, the seed allowed per Scotch acre being from 3 firlots

to 14 pecks. The ordinary yield varied from 6 to 10 bolls. The best

understood and most extensively cultivated cereal was oats, of which a

boll was sown per Scotch acre, and from 4 to 8 bolls reaped. By this

time turnips had begun to take the place of pease; but some thirty years

previously, pease and tares were largely cultivated. When land was sown

with grass seeds for one year's crop of hay, and had to be broken the

year following, the quantity sown was usually from 12 to 15 lbs. of red

clover and a bushel of English rye-grass per English acre. Along with a

similar quantity of rye-grass, from 8 to 10 lbs. of white clover and 4

lbs. of red clover was sown for two or more years grass. Two hundred

stones of hay were often produced per acre, the price varying from 4d.

to 4½d. per stone when in the rick, and from

6d. to 8d. when old. The implements of husbandry were of a very

primitive description. The old Scotch timber plough has only just begun

to be superseded in some cases by an improved implement named Small's

plough. Its mould board was cast metal. Previous to this time oxen were

generally used for draught, and horses were not much employed except for

driving coal and lime or grain until near the close of last century. The

harrows consisted of four iron "bulls" or bars, jointed together by four

thin "slots," and each "bull" contained five iron teeth or tynes. The

rollers used were mostly made of wood. Thrashing mills were almost

unknown. Farm servants were by no means scarce ninety or a hundred years

ago, yet their wages increased greatly about that time. Ploughmen and

others employed in husbandry received from £5 to £8, 8s, with their

maintenance, yearly; women got from £3 to £4, with board; and

day-labourers (men) received from 10d. to 1s. in winter, from 1s. to 1s.

4d. in summer, and 1s. 6d. in harvest; women in summer got from 6d. to

8d., and in harvest from 8d. to 9d., and their board. Hours were similar

to those of to-day. Roads were ill-made and badly kept. A word as to the

live stock of the county. The sheep-walks were first inhabited by

the blackfaced breed, but Cheviots came into vogue, and it was about a

hundred years ago that the "battle" blackfaced versus Cheviots,

which still rages, began. Farmers had recourse from one breed to the

other as circumstances suggested or demanded. Both are essentially hill

breeds, and in consequence of the superiority of the Cheviot wool over

that of the blackfaced, the former became and continued to be the

dominant breed. From 7 to 8 fleeces of Cheviot wool made a stone of 16

lbs., for which the usual price was from 12s. to 16s.; a similar

quantity and weight of wool from the blackfaced breed brought only from

6s. to 7s. 6d. The average weight of Cheviot ewes when fed upon common

hill pasture was 9 lbs., and the wedders 11 lbs. per quarter ; but on

rich pastures they were generally fed up to from 12 to 15 lbs. per

quarter. The blackfaced when fed weighed from 9 to 14 lbs. per quarter.

Ewes of this breed sold at from 11s. 6d. to 13s.; wedders, from 12s. to

13s. 6d.; hoggs, from 7s. 6d. to 8s.; lambs, 3s. 6d. to 5s.; and ewes

with lamb, at from 10s. to 11s. 6d. Both breeds were smeared in the end

of October with a mixture of tar and butter, the usual mixture being 1½

stones of butter and 10 pints of tar, which smeared from 60 to 70 sheep.

One man smeared from 20 to 30 sheep per day, and the expense of smearing

each sheep was about 4½d. The cattle generally

kept in the higher districts were narrow-built, flat-ribbed animals, and

weighed from 30 to 40 stones each when fed. Most of the cows were cross

between the native cattle and the Holderness breed. In the lower parts

of the county, where there was more fencing, cattle were superior to

those in the uplands, and when fed off at three years old, weighing from

50 to 60 stones each, they realised from £15 to £17. Little attention

was given to dairying. Horses were chiefly bought in from other counties

; few were bred in Selkirkshire. The prevailing breed were from 14 to 15

hands high, and were worth from £10 to £20 each.

Coming within the present century, we find that there

was no exceptional enterprise shown for some considerable time after its

advent. Nevertheless, the march of improvement started, as we have

noticed, in the " fall " of last century, continued more or less

manifest, and as time wore on the agriculture of the county became more

active. During the first three decades of the present century creditable

progress was made in the improvement of live stock, but the advancement

made in other departments of the farm was less marked. Fresh blood was

from time to time infused into the herds and flocks, and in some

instances entirely new breeds introduced for crossing purposes. In the

parish of Yarrow, for example, about 2000 Leicester sheep, in addition

to the customary blackfaced and Cheviot breeds, were enumerated in 1830,

and this breed was little known thirty or more years previously. The

most noteworthy change effected, however, in the matter of stock

breeding was the use of shorthorn and Ayrshire cattle. A cross between

these breeds constituted a handsome hardy and useful animal, and of this

blood-mixture there were about 3000 cattle in the

county in 1831. Highland cattle too were introduced during the

second or third decade, and were depastured on the sheep-walks with

profit. The mixed system of grazing cattle and sheep together was found

to do very well. I had an interview with an old farmer in the county,

whose exceptional age and intelligence enables him to look back with

familiarity upon the affairs of seventy or eighty years ago, and

contrast them with those of to-day. He informed me "that the cattle of

the county then were largely composed of Dutch cows. Blackfaced and

Cheviot sheep covered the hills, the latter gaining ground on the

former. They were greatly improved after the change of the breeds, the

real Cheviots being hardy, healthy animals; but latterly they have got

much softer and less adapted for the severe climate. At the May term of

1816, ewes and lambs cost 31s.; two years later they fell to 10s., and

continued very low for a number of years. Horses were much lighter than

they are now. Cattle were greatly increased in value and utility by the

introduction of shorthorns. As regards labour, hind's wages were

generally £12 in money, 65 stones of meal, potatoes, and keep for a cow;

shepherd's wages usually took the shape of keep for 35 to 45 sheep, and

a cow, and so much meal. With few exceptions, the principal farm

implements consisted of a wooden plough, timber harrows, and sledges

with shafts for the hill sides. Rents were all paid in money. Oats, bere,

and small patches of pease were grown. Every farm had its own dairy, and

in addition to the produce thereof most farmers made a few ewe cheeses

every year, i.e., cheese from ewes' milk." As to the progress

made agriculturally within the three decades intervening between 1830

and 1860, a good deal might be written. A great deal of good work was

done in draining as well as reclaiming land, especially during the last

decade of the three. Some planting was also performed on the different

estates, and the appearance of the country was materially improved,

while by the prudent use of manures its productiveness was substantially

increased.

Progress of the Past Twenty-five Years.

Notwithstanding the large extent of land reclaimed

between the years 1845 and 1860, the cultivated area of the county has

handsomely increased within the past twenty-five. Since 1860 a large

acreage of hill land has been converted into productive soil by of

process of ploughing, draining, and liming, and in many cases the work

of reclamation was very laborious and expensive. This arose from the

fact that much of the land in its natural state was not only steep, but

overrun with huge boulders, heather, and whins, while some of it was

submerged by water. The removing of these obstacles involved great

trouble and expense, and rendered the operation of improvement tedious

and difficult to accomplish. Since 1860, vast improvements have been

carried out in the direction of draining and re-draining old land and

squaring up fields. In fencing too a great deal of good work has been

done, while it would almost seem as if building had been continuously

going on for many years. At any rate, numerous dwelling-houses and farm-steadings

have been erected during the past twenty-five years, and the county is

now well provided with these. The making of private roads and the

introduction of water to farm-steadings have also to be mentioned as

improvements of recent date.

The manuring of land, at one time so imperfectly

understood, has been the object of no little investigation and study of

recent years. On two large farms in the lower division of the county,

Hollybush and Newhall, instructive experiments

were conducted, well calculated to throw increased light upon the

mysteries of land feeding. Their object was to determine whether

phosphates, potash, or nitrogenous matter was most needed in the soil.

For this purpose five adjacent ridges were selected in each case, and

about fifty yards measured off and manured as follows:—Plot (1)

phosphate alone; (2) phosphate and potash salts ; (3) phosphate, potash

salts, and nitrate ; (4) potash salts and nitrate; and (5) nitrate

alone. The phosphates were applied in two different forms—as

superphosphate and as ground mineral phosphate. The latter was applied

in the form of the finest flour, and the quantity of phosphate was

exactly the same in both forms. In each case the superphosphate produced

a heavier crop than the ground phosphate, but the increase in favour of

the former was not very striking. Indeed the difference was trifling,

and it is probable that if the two forms of phosphate had been applied

on the basis of equal money value, the ground mineral would have held

its own with the superphosphate. The results strikingly illustrated the

peculiarly depressing effect of potash when applied to the turnip crop.

This ingredient was more depressing in these two cases than it has been

discovered to be in almost any other part of Scotland. The progress of

the past twenty-five years in the improvement of land has obviously been

eclipsed in the department of stock-breeding. The light-weighted horses

of forty or fifty years ago are no longer to be met with; the ungainly

ill-bred cattle of the same age have been superseded by stronger and

more useful stock of shorthorn blood. The alteration in the existing

breeds of sheep has not been so pronounced, but some of these have

perceptibly benefited from the increased attention devoted to their

management. We were told that the characteristics of the Cheviot breed

have suffered from an attempt to increase the size and weight of the

sheep; but judging from the quality of the present class of Cheviots, we

are not disposed to attach much importance to this allegation. Whether

it is true or not, there is no blinking the fact that Selkirkshire at

the present day is capable of producing as good Cheviot, blackfaced, and

half-bred sheep as almost any other county in the United Kingdom.

Before proceeding to detail the various systems of

farm and estate management prevalent in the county, it may be of

interest to show in figures the exact area under cultivation, and its

increase during the past twenty-five years, thus:—Arable area in 1857,

14,441 acres; 1868, 2084; 1874, 22,456; 1880, 23,228 ; and 1885, 23,302.

Increase since 1868, 2516 acres; 1874, 864; and 1880, 92. It may be

explained that the returns for 1857, drawn up by the Highland and

Agricultural Society, excluded all holdings under £10 of rent, and

therefore the figures of that year bear no reliable comparison with

those of 1885. It will be seen, however, that enfeebled though the

spirit of improvement has been by a long succession of unfavourable

seasons, the plough has been gradually extending its control. Spreading

the increase over the seventeen years during which it has extended 2516

acres, the annual gain would be fully 142 acres; but, as the above

figures clearly show, the acreage reclaimed during the past five years

was scarcely two-thirds of that number.

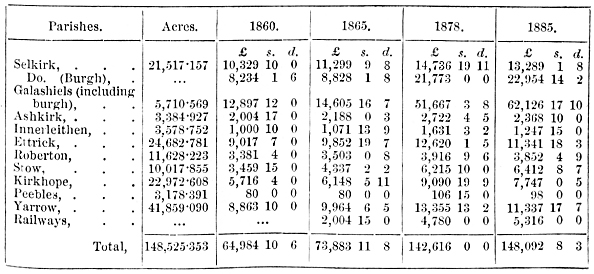

Having thus exhibited the gradual development of the

cultivated area, it may also be of interest to indicate the advance in

the valuation of the several parishes and the two burghs within the

county, at various periods since 1860. This is shown by the following

statement, as well as the extent of the different parishes lying within

the confines of Selkirkshire:—

Until this year it will be observed there has been a

gradual rise in the valuation of every parish; but that, with exception

of Stow, which has increased £196, 18s. 7d. since 1878, a considerable

decline has taken place in the rural valuations for 1885. In the totals

for the years mentioned, however, an increase occurs of £8901, 1s. 2d.

from 1860 to 1865; £68,730, 8s. 4d. from 1865 to 1878; and £5476, 8s.

3d. from 1878 to 1885. The decrease of recent years in the valuation of

the rural districts has been more than made up by the rapid growth of

the burghs of Selkirk and Galashiels.

Systems of Farming.

Details of Improvements.—Having recently visited

a number of the principal farms in the county, we are enabled to speak

from personal observation regarding the various systems of farming

pursued, and most of the improvements effected during the past

twenty-five years. We have to acknowledge our gratitude, however, to the

numerous farmers and landowners who, by letter, placed us in possession

of so much valuable and interesting information concerning their farms

and estates ; and, for brevity's sake, we have embraced the notes thus

collected in detailing the information gleaned on our recent tour. We

shall therefore describe the various farms in the order in which we

visited them, starting at the extreme eastern point of the county.

Amongst the more important lowland farms which cluster around the busy

town of Galashiels is the carefully-managed farm of Nether Barns,

tenanted by Mr Adam Brydone. It extends to 510 acres, 50 acres of which

are under pasture. The soil is partly clayey and partly gravelly, the

latter prevailing on the side of the farm skirted by the Tweed. Under

the five-shift rotation crops do not bulk so largely on this farm as on

some others, but they yield fairly well as to quantity and weight. Land

for turnips, if not manured on the stubbles before being ploughed in

autumn, is dunged in the drill, and gets a liberal supply of artificial

stimulant besides. The value of the farm has been considerably enhanced

since it came into Mr Brydone's possession, liberal outlay having been

made in draining and liming, with satisfactory results. It carries

crossbred shorthorn cattle and half-bred ewes. No cattle are bred on the

farm, but from twenty-five to thirty are fed on turnips, hay, and cake,

and are sold fat in spring, weighing from 50 to 60 stones. The ewes are

kept for breeding purposes, and most of the lambs are sold during July

and August, any remnant that is left being fattened. The horses are

stylish short-legged Clydesdales, and work about 100 acres a pair. Mr

Brydone calculates farm wages to have risen at least 3s. per week since

1859, and rents to have sprung from 15 to 30 per cent. in the same time,

according to the nature of the soil.

The farm of Hollybush, extending to about 600 acres,

is occupied by Mr Walter Elliot. It is nearly all arable, but a

considerable extent has lain under pasture for a few years. The soil is

chiefly formed of clay, and rests on a hard impervious subsoil of till.

Under the five-course rotation—viz., oats, turnips, oats or barley, and

two years' grass—however, it yields fairly well—oats from 4 to 4½

quarters per imperial acre, weighing from 42 to 44 lbs. per bushel, and

barley about 4 quarters, weighing from 56 to 57 lbs. Very little wheat

is grown, but this cereal was raised to the proportion of 26 bushels to

the acre on a small patch of land in 1884. For turnips, land is ploughed

heavily in the autumn, and allowed to lie under the action of the frost

during winter. The spring work is greatly regulated by the condition of

the land, whether foul or clean. If foul it is grubbed, and sometimes

ploughed a second time, and harrowed repeatedly. At one time Mr Elliot

dunged the stubbles before ploughing, but latterly he has put the bulk

of the farm-yard manure on to lea, so that the turnip is the second crop

to benefit by it. A small quantity is often spread in the drills on land

that did not get manure when lea, and generally an allowance is made of

from 5 to 6 cwt. of artificial manure to the acre. The artificial

mixture consists of bones, guano, bone meal, and superphosphate. The

cost of this manuring an acre is about 32s. The turnip crop is by far

the most expensive on the farm. Some idea of its cost (including labour,

manure, and seed) per acre, from the time the stubbles are ploughed

until the crop is finally hoed, will be gathered from the following

statement:— When the land is moderately clean, ploughing per acre costs

about 10s., grabbing 2s., harrowing 2s. 6d., rolling or dragging 1s.,

drilling 5s., sowing manure 9d., sowing turnips 9d., seed per acre 1s.

9d., hoeing 5s. 6d., drill-harrowing 3s., and second hoeing 2s. 6d. =

35s. 5d.; total cost, including 32s. for manure, £3, 7s. 5d. Potatoes,

which are only grown for home use, are similarly manured. Mr Elliot has

greatly increased the extent of the arable land on the farm, as well as

enriched the soil since he entered it in 1855. It was largely under

heather, bog, whins, and water. Its rental was then only £197, and now

it is £454; but in 1878 it was over £600. A large extent of the land

reclaimed, which consisted of impervious tilly clay, was drained,

principally with tiles, to the depth of 3 feet, the drains being 15 feet

apart. The cost of this per acre was from £9 to £10. In its original

state the land was overrun with huge boulders, and many of these had to

be removed before the plough could set to work. After the first

ploughing, which was a tedious process, lime was applied to the extent

of 6 tons per acre. This was followed by cross-ploughing, and then oats,

of which two successive crops wore taken. A great impediment to this

enterprise was the superabundance of moisture and the number of old

hedges to be removed. The total cost of reclamation is estimated as

follows:—Ploughing and hedge and stone digging, £1100; draining, £3500;

liming, £2160; and fencing, £900,—total cost, £7660. Average cost of

reclaiming 530 acres, as nearly as possible, £14, 10s. In addition to

this amount, a sum of £600 was spent in removing a small sheet of water

from the centre of the farm. The landlord built an excellent farm-steading,

a large extent of dykes, and advanced money for a considerable portion

of the drainage works referred to. Mr Elliot keeps shorthorn cows, a few

of which are bred on the farm. He feeds a fair number of cross bullocks,

giving them from 56 to 84 lbs. of turnips per head per day, along with

from 4 lbs. to 10 lbs. of an artificial food, combining linseed cake,

decorticated nut cake, cotton cake, bean meal, and Paisley meal—the

supply gradually increasing as the animals mature—and one feed of cut

hay per day, from 8 to 10 lbs. Straw is supplied in abundance. It would

be well if all farmers adopted Mr Elliot's plan of ascertaining the

value of his stock before selling them. Every animal is weighed, and has

been for many years, before being sent into the market. The farm is

largely stocked with half-bred sheep, and there has also been a small

flock of Oxford downs kept for the past eighteen years. Their food

during summer consists solely of the grass they gather in the parks; but

during winter and spring, if the weather is bad, half-bred sheep get

turnips and hay, and sometimes a small quantity of artificial food. Mr

Elliot estimates the cost of keeping half-bred ewes during a whole year

at about 30s. a head on his farm, but they can be kept at a little less

where there is a large run of rough pasture attached to the arable land.

Hollybush is well supplied with the necessary buildings, and is one of

the most skilfully managed farms in the county.

Mr John Riddell, one of the best farmers in the

county, succeeded his father in the occupancy of the farm of Rink, which

has an area of fully 500 acres, and is wrought under the five-shift

rotation. When the late Mr Riddell entered it in 1848, the farm was

largely under hill pasture, and even ten or twelve years later there was

a considerable portion of it in the same condition. Now, however, it is

wholly arable, but Mr Riddell's experience in crop-growing is similar to

that of his neighbour Mr Brydone. The weight of crops per bushel is

invariably good, but as a rule the returns bulk badly—often as low as 3

quarters per acre. Mr Riddell ploughs his stubbles as early as possible

after harvest, and as a large proportion of the land, which consists

chiefly of light gravel and cold clay, is very steep, it has to be

ploughed with one furrow, the fur being from 10 to 12 inches deep. The

land is all dunged when in lea before ploughing for the oat crop, and

one-half of it at least gets another supply of farm-yard manure after it

is drilled for turnips, along with 5 cwt. guano and bones per acre, an

increased supply of the latter being given where there is no farm-yard

manure put in the drill. Land for potatoes, of which only 5 or 6 acres

are grown, is all dunged on the stubble, artificial manure being added

before planting begins. At one time Mr Riddell fattened about 60 head of

cattle annually; but, being within three miles of Galashiels, he

latterly started a dairy, which is skilfully and successfully managed. I

shall reserve my information regarding it, however, for a later and more

appropriate place in my report. Few farms are better supplied with

buildings than Rink. Some three years ago the landlord expended £1000 on

buildings free of interest, and the farm-steading is one of the most

commodious and convenient in the county. Besides the dairy herd, Mr

Riddell keeps over 300 half-bred ewes, from which he raises nearly 500

lambs. From 100 to 200 of the latter are sold at St Boswell's Fair, and

the rest are fattened during winter, and sold in February or March. The

horses on the Rink are well-bred Clydesdales—eligible for entry in the

stud book. Five pairs are found sufficient to work the farm under the

five-shift rotation. Mr Riddell says " farm wages have nearly doubled

since 1858."

One of the largest farms on the banks of the Caddon,

and in the parish of Stow, is Caddonlee. It has an acreage of 850, of

which 540 acres are arable, and is occupied by Mr William Lyal.

Reclaimed from hill, the soil is very variable and lacks depth in many

parts. None of it is very good. The present tenant entered the farm in

1870, after which he reclaimed about 150 acres. Since then, too, most of

the farm has been limed, and substantial improvements have been effected

in the shape of draining, road-making, and building. About £1800,

chiefly Government money, was spent in draining, the landlord giving

£500. In building houses and dykes the landlord spent about £1100, and

paid half the cost of making new roads, the tenant bearing the other

half. Mr Lyal farms under the five-course shift, as prescribed by his

lease, keeping the farm as largely under grass as practicable. Crops

have not yielded so well of recent years as previously; the average

return is about 4 quarters barley, and from 4½

to 5 quarters oats, per acre. The system of preparing land for turnips

is similar to that of the farms already described. Grubbing in spring is

almost always required, and sometimes the land has to be ploughed a

second time before it can be thoroughly cleaned. Dung is applied to the

turnip break as far as it goes, artificial manure being also allowed to

the value of about £2 per acre. Bones and superphosphates are more

extensively used than guano. The cattle on the farm are shorthorn

crosses, bought in when six quarters old. Part of them are fed off in

winter, and part sent to the butcher off the grass in summer. They

usually number from 30 to 40, and weigh from 50 to 60 stones when sold.

The farm also carries about 400 half-bred ewes, half the lambs of which

are sold at weaning time, and the remainder are fattened on the farm

during winter. All the sheep get turnips during winter. Mr Lyal has a

good stock of Clydesdale horses, the allowance to a pair being about 100

acres.

Though only a small portion of Stow lies within the

county of Selkirk, it is the more important division of the parish from

an agricultural point of view. It contains several extensive and

energetically managed holdings, in addition to the farm of Cad-donlee

just described. Of these I may mention Laidlawstiel, tenanted by Mr

Dunn—to which a good deal has been added through reclamation since 1860—Torwoodlee,

Kewhall, Black -haugh, Whitfield, and Crosslee. Torwoodlee, now occupied

by Mr Gibson, has an area of 1000 acres, about 591 acres of which were

reclaimed by the late Mr Elliot. Some 130 acres are under hill pasture,

while close on 100 acres are covered by wood. The late Mr Elliot was one

of the pioneers of agricultural improvement, and with scant proprietary

assistance made a lasting impression on the land he occupied.

Mr Thomas Elliot is tenant of the farm of Blackhaugh

and also of Meigle, the former extending to 1060 and the latter to 800

acres. Meigle is chiefly a pastoral farm, there being only some 300

acres arable, but as many as 600 acres are under cultivation on

Blackhaugh. The land on Blackhaugh is thinish clay resting on a stiff

retentive subsoil. Crops at one time were much heavier than they have

been since 1874, and for two or three years back the yield has shown a

marked decrease. This circumstance seems utterly unaccountable. All the

dung made on the farm is given to the land, all that is prepared by

autumn being spread on the stubbles before the plough is set to work,

and the remainder in spring. Land thus treated for turnips is

cross-ploughed in spring, or grubbed, as circumstances demand. When

thoroughly cleaned it is drilled, and from 5 to 7 cwt. of bone meal and

guano are allowed per acre. Since 1849 Mr Elliot—following up the

footsteps of his exemplary father the late Mr Elliot, Torwoodlee—has

reclaimed 535 acres of land from hill, in which operation he was partly

assisted by Government money. The landlord fenced the farm with stone

dykes 5 feet high, the tenant providing the stones. When mutually borne

in this manner the dykes cost about 2s. 3d. per rood of six yards, but

some walls cost 3s. The farm is stocked with shorthorn cross cattle, and

about 900 sheep. Of the former from 20 to 30 are annually fattened,

chiefly on turnip, cake, and ' meal. During the present year fewer

cattle and more sheep have been fed than usual. No cattle are bred on

the farm, but a large number of lambs are raised. These are partly sold

at St Boswells, from 9th to 12th August, and the youngsters retained are

as a rule grazed away from the farm during the winter season.

Immediately after the lambs are weaned, the sheep are all dipped with

Begg's patent dip, which is found to be sufficient for the whole year.

The flock comprises half-breds, cross sheep, Cheviots, and blackfaced.

The arable portion of the farm is worked on the five-shift

rotation—viz., (1) corn, (2) turnips, (3) corn, and (4) and (5) two

years grass—the allotment being 100 acres to the pair of horses.

In the immediate neighbourhood of Blackhaugh is the

well-managed farm of Newhall, occupied by Mr Andrew Elliot. Some 400

acres in extent, Newhall is largely under Cheviot ewes. These are mated

with a Leicester tup, and good cross lambs are obtained. The farm, which

was formerly in possession of Mr Elliot's father, the late Mr Elliot of

Torwoodlee, has been mostly all limed by the present tenant, while not a

little of the land was drained, the drains being only 15 feet apart on

some fields. The farm of Crosslee is situated in the extreme northern

corner of the county, and has just been let to Mr Alston, better known

as a Peeblesshire farmer. It was vacated last May by Mr Hall, by whom it

was greatly enriched and improved.

The greater part of the land occupied by Lords A. and

L. Cecil, Orchardmains, lies within the county of Peebles, but a portion

of it extends into Selkirkshire. Their Lordships hold from 3000 to 4000

acres, some 800 acres of which are arable. The higher land is chiefly

depastured by blackfaced sheep, which number over 400; while the lower

is under Leicesters, Cheviots, and half-breds to the number of about

1400. We do not intend entering into the system of arable farming

pursued on Orchardmains and Newhall, but it is worthy of mention that

these farms carry a stud of from 70 to 80 horses of various sorts. The

Clydesdale portion of it is well known for its show-yard success of

recent years. It is not so generally known, however, that within the

last year or two Lords A. and L. Cecil have turned their attention to

the improvement of the admirable race of Highland ponies, which they, in

common with many others, have seen are in the ordinary course fast

deteriorating. With this purpose in view, they some two years ago,

formed a pony-breeding stud by purchasing seven mares of the pure

Iceland breed. These ponies stand 12 hands high, are exceedingly hardy,

have strong legs and backs, and are noted for their endurance and

sure-footedness. They have somewhat large heavy heads, and, though very

fast, are deficient in style and action. But in the selections made

great care was taken to secure animals with good shape, clean limbs,

free movement, and sound constitution. They stand about two hands higher

than the Shetland pony, and are thus better adapted for raising the

class of animals most in demand for polo ponies, shooting ponies, &c.

Along the Vale of Yarrow, crop-growing is not so

largely pursued as in the districts already noticed, the land being

higher and in many cases less productive. In the neighbourhood of

Selkirk lies the extensive farm of Philiphaugh, which has been tenanted

for twenty-five years by Mr Scott. It is pretty level, being to some

extent haughland, and has been greatly improved within the past

twenty-five years. It is hemmed in on one side by the Ettrick, and can

scarcely be classed in the Yarrow district. It was the first holding to

arrest our attention, however, as we entered the Vale of Yarrow, and is

specially noticeable from its peculiarly flat surface, its well laid-off

fields, and magnificent farm-steading. The farm-steading is probably the

best in the county.

A few miles north-west of Philiphaugh is the farm of

Tinnis, tenanted by Mr George Elliot. It extends to 2312 acres, of which

only 300 acres are arable. The soil is generally light and stony, but

clay is also observed on some parts, the subsoil being cold and

retentive. Mr Elliot adopts no specific rotation, but allows the land to

lie as long under grass as practicable. Cereal crops are invariably

light, and the braird sometimes suffers from frost and wet weather

during spring. Oats, which is almost the only cereal grown, seldom

weighs over 42 lbs. per bushel. Turnips yield fairly well, but are often

irregular and depreciated by "finger-and-toe." The most difficult crop

to cultivate, however, is grass, which is almost invariably too thin.

Since 1876, 115 acres of hill land have been reclaimed. The landlord

advanced money for draining and fencing at 5 per cent. interest, and the

tenant provided the lime used. About 12 cattle are annually bred from

cross and Ayrshire cows. The 300 arable acres are wrought with four

horses, but the land is not regularly cropped. The feature of the farm

is its stock of sheep, which number from 1800 to 2000, all Cheviots. The

half of them are grazed on the hill portion of the holding all the year

round, but the other half get turnips for about two months in spring.

The turniped ewes are mated with a Leicester tup, but the purely hill

sheep produce Cheviot lambs. The lambs are sold in August and the ewes

in October. The ewes are kept until they are six years old, because

hoggs are precarious to winter. Sometimes as many as 5 or 6 hoggs out of

the score die of braxy between August and May. Lambing among the

turniped ewes begins about the 5th April, and among the hill ewes about

a fortnight later. Sheep are clipped from the 15th to 20th of June, and

the average weight of wool runs from 3½ to 4

lbs. Dipping is performed in September and October, and sometimes also

in February and March. The price of wool sold off this farm in 1876 was

32s. per stone of 24 lbs., and this year it only brought 18s. 6d. The

average death-rate runs about 1½ to the score

during the year ; but it varies from | to about 2 sheep according to the

nature of the seasons. Most of the deaths are caused by braxy and

louping-ill, and in some years sturdy is prevalent, especially in wet

years. "The last ten years," says Mr Elliot, "have been very

unfavourable for sheep farming—every good year having been followed by a

bad—and it has almost been impossible to keep a Cheviot stock up to a

proper standard of excellence." During the past ten years or so, prices

have varied on Tinnis from 45s. to 18s. in the case of Cheviot ewes,

19s. to 9s. in the case of wedder lambs, and 21s. to 7s. in the case of

ewe lambs.

Mr John V. Lindsay, who

occupies the extensive farm of Whitehope on a lease of fourteen years,

owns a flock of 3800 sheep, of the blackfaced and Cheviot breeds. The

average death-rate on this farm is also estimated at 1½

to the score. The average yield of Cheviot wool (washed) is 3½

lbs., that of blackfaces (unwashed) being 4½

lbs. In dipping, which takes place in August and February, 1½

gallon of carbolic oil is used, costing 1s. per 100 sheep. During a

severe snowstorm in winter sheep get hay, but at other times they get

nothing-additional to what they gather for themselves. Lambs are sold in

August, and cast ewes in October—at Hawick generally for Cheviots—at

Peebles for blackfaces. The arable land is worked on the five-shift

course, and is allowed on an average 6 cwt. per acre of artificial

manure annually. All the oats grown are consumed on the farm, besides

about 10 tons of cake per annum. On entering the farm Mr Lindsay got

what new buildings were required ; all the fences were repaired, and

tile drains sunk, and hay-sheds built, at 5 per cent. interest. Since

then he has limed the arable portion of the farm at his own expense. The

crops grown consist of oats, hay, and turnips. Mr Lindsay recently

grazed more cattle than usual on the mountain pasture in place of sheep,

as he found the former improved the pasture, and that they thrive better

than sheep.

The farm of Mount Benger, of which 1300 of a total

area of 1400 acres are under pasture, is occupied by Mr Linton, and is

worked under the seven and eight shift rotation. When Mr Linton entered

the farm in 1866 there were about 1300 roods of "sheep" or open drains

in working order, and since then as many again have been cut. He has

cleaned out the older drains three times, and has tile-drained 23 acres

of hill ground. Some £500 worth of lime has been applied to the land

since 1866. Land for turnips is ploughed in the fall, and either grubbed

or ploughed a second time in spring. The farm-yard manure is chiefly

spread on the stubbles, and artificial manure to the amount of from 5 to

6 cwt. sown in the drills just before the turnips are sawn. In the

artificial mixture about 3 cwt. of bone meal, 2 cwt. superphosphate, and

¾ cwt. of nitrate of soda are given to the

soil. Thirteen or fourteen calves are bred every year from cross cows

and a shorthorn bull. The farm, . however, is mainly stocked by Cheviot

sheep, of which a very large flock is kept. Most of them are summered

and wintered on the hill, except during severe snowstorms, when they get

meadow hay, but a portion are grazed in parks. These get a few turnips

as well as hay during winter. All the lambs are sold in August, and the

draft ewes are then drawn into parks and mated with a Leicester tup, the

half-bred lambs being sold at St Boswells in August. The eild sheep are

clipped about 25th of June, the wedder hoggs yielding on an average from

4¼ to 4½ lbs. of

wool each. Ewes are clipped in the first week of July, and yield from 3½

to 3¾ lbs. wool. Mr Linton dips his sheep

twice a year—in August and the first of March. The dipping operation is

performed in a swimming bath, four men being required to carry on the

work. The dip mainly consists of pitch oil, which costs 6d. a gallon,

and a hundred sheep can easily be twice dipped at the moderate cost of

2s. The death-rate in the Mount Benger flock averages from 12 to 15 per

cent. of young stock, and about 6 per cent. of old sheep.

Further up the vale still, and at an elevation of

from 800 to 2300 feet, is the farm of Dryhope, tenanted by Mr J. Muir.

Having a total acreage of about 3500, of which only 68 acres are arable,

Dryhope is chiefly under sheep—two hirsels of blackfaces and one of

Cheviots. Lambs and draft ewes are sold off from August to October. The

arable land is of good medium quality, and is wrought by a pair of

horses. The hill is partly covered by sprett and heather. Peat moss is

abundant on the highest parts. Arable land is wrought under the

five-shift rotation, and produces fairly good crops as a rule, but

harvest is often late and grain light. Mr Muir keeps almost the only

herd of shorthorn cattle, if not the only pedigree herd in the county.

The bulls are sold when about one year old. Sometimes a few Highland

cattle are wintered on the farm and fed off on grass during the summer.

Of the unbroken pasture some 53 acres are enclosed.

The farm of Sandhope, tenanted by Mr Laidlaw, is also

in the parish of Yarrow. It contains 140 acres arable, hard gravelly

soil 20 acres permanent pasture, and about 2000 acres mountain land, and

was rented at £768, 2s. 4d. in 1880. A lease of nineteen years expired

in that year, when the tenant got a reduction of

24½ per cent. For the first fourteen

years of the lease the tenant had full freedom of cropping, excepting in

taking two white crops in succession. The last five years he was bound

to cultivate on the five-shift rotation. No straw, fodder, or dung were

allowed to be carried off the farm, except by rye-grass hay. Artificial

manure is consumed annually on the farm to the extent of about 4 tons,

and the quantity of feeding stuffs 5 tons. The cost of producing corn,

turnips, and hay per acre on Sandhope were estimated in 1880 as

follows:—Corn 20s. in rent, 3d. in rates and taxes, 20s. in seed, 27s.

in cultivation and harvesting, 20s. in labour (including thrashing and

marketing); turnips 20s. in rent, 3d. in rates and taxes, 3s. in seed,

40s. in manures, 40s. in cultivation, &c.; hay, 20s. in rent, 3d. in

rates and taxes, 14s. in seed, and 14s. in cultivation, &c. The average

return of hay-in 1878-79 was 2 tons per acre, amounting in value to £4.

Of oats the average seeding per acre is from 6 to 10 bushels. The

improvements executed on the farm during the recent lease consisted of

the breaking up of some 70 acres of pasture, the building of a new straw

and corn barn and stables, the construction of a new farm road and

bridge, the total cost being £1450 Government money, for which the

tenant paid interest at the rate of £6, 14s. per cent.

A farmer, writing from the higher reaches of the

parish of Yarrow, says:—"I am interested in two farms with a combined

acreage of over 6000 acres. They are purely pastoral holdings, and carry

sheep in the proportion of one sheep to every 2 acres. Excepting about

600 Cheviots, the sheep are all of the blackfaced breed, but previous to

1860 I believe only Cheviots were kept. The change in the breeds was

necessitated by the severity of the winter in 1860 and subsequent years.

The holding is very high-lying, skirting the Blackhouse heights, and

suffers very much from heavy and protracted snowstorms. Even last winter

800 of the sheep suffered severely for a period of about six weeks from

snow, which, after a succession of thaw and frost, became firm and

difficult to break. A considerable portion of the stock has had to be

removed five times to the lower parts of the country to be fed on hay. I

entered the farms in 1871. About 300 hoggs are regularly pastured

elsewhere during the winter. Lambs for sale are disposed of in August

and draft ewes in October."

Throughout the Ettrick and higher districts of the

county the farming systems differ very little from those adopted in the

Vale of Yarrow. The soil varies from tenacious clay to gravelly haugh

land. Much of the clayey land is difficult to dry sufficiently, even

though drains are closely put in. The wet seasons of late have seriously

damaged the land in many cases, drains having been silted up and

rendered useless. A great deal of land was broken up in the higher

districts of the county, some fifteen or twenty years ago, and on some

farms it has not been profitable. "Where it has been much cropped,"

writes an Ettrick farmer, "and not liberally manured, I consider it is

in a worse and more unremunerative state than it was before being broken

up, especially where the land was wet and needed extensive draining."

The crops grown in these districts are chiefly oats and turnips. A great

deal of the arable land was wrought for many years under the five-shift

rotation, and that, in the opinion of an extensive upland farmer, "to

the ruin of the county." Land should not be ploughed, he maintains,

oftener than every six or eight years. Cheviot and blackfaced sheep are

kept in the hills and half-breds on the arable land. Sheep-farming is

the main industry, and cultivation is not so extensively practised as in

the lower districts.

A farm with a total acreage of 1050, of which 772

acres are mountain pasture and 278 arable, is one of the most important,

agriculturally, in the district. The soil is chiefly light, and is

cropped thus:—Oats after lea, turnips following, third year sown with

oats or rape, and then pastured for two years. Its rental in 1880 was

£418, 11s., and in addition to this the farm was charged, in taxes,

rates, and insurance, to the amount of £15, 6s. 7d. It carries on an

average over 1000 animals, consisting of Clydesdale horses, shorthorn

cross cattle, and half-bred and blackfaced sheep. About 70 half-breds

are annually fattened on the farm, and the cattle are chiefly sold as

store or breeding stock when two years old. Artificial manures are

annually used on the farm to the extent of 14½

tons, or to the value of £137. Artificial feeding stuffs are also

consumed to the value of £98, 12s. The cost per acre of producing each

crop grown upon the farm has been approximately estimated thus:—Oats

25s. in rent, 1s. in taxes, 16s. 6d. in seed, 20s. in cost of

cultivation and harvesting, 3s. in labour (including thrashing and

marketing), 1s. in sundries (including tradesmen's bills); turnips 25s.

in rent, 1s. in taxes, 2s. 6d. in seed, 60s. in manure, 24s. in

cultivation, &c., 9s. in labour, &c, 1s. in sundries, &c. In 1875 the

average yield of oats per acre was 4½

quarters, along with about 150 imperial stones of straw—the corn

bringing 28s. per quarter, and the straw 8d. per stone of 22 lbs. In the

following year the return of corn was rather higher, but straw less. The

price of the corn, however, had fallen to 23s. 6d. per quarter. In

1878-79 oats yielded 4 quarters and 120 stones of straw, the price of

the former being 21s. 1d. per quarter, and the latter 6d. per stone of

22 lbs. About an eighth of the seed sown is annually bought. In 1876

some 9 acres of moorland were reclaimed and added to the arable farm.

The gross amount expended in labour on the farm during the year 1878-79

was £600, 4s., and for previous four years it was £1274, 12s. 2d.

Amongst the most skilfully managed farms in the parish is that tenanted

by Mr John M'Queen. Oakwood contains 1000 acres, and is attached to the

sheep farm of Fauns, carrying about 28 score of blackfaced sheep. The

rental of Oakwood when the farm was stocked was £750, and with interest

on drains, &c, it is now rented at £833; the farm of Fauns, which only

came into Mr M'Queen's possession some two years ago, is rented at £200.

When Mr M'Queen entered Oakwood there were only about 500 acres arable ;

since then he has broken up, limed, fenced, and improved 200 acres,

about the half of which required draining. Some 60 acres of hill ground

were drained at unusual depth, and limed on the surface with gratifying

results. Of the land broken up 25 acres were converted into meadow,

which is frequently top-dressed, while a portion of it has never been

ploughed again. The farm is largely fenced with paling and wire fences,

in the erection of which the tenant expended a good deal of money.

Upwards of 1900 tons of lime have been spread on the farm by the present

tenant, applied at the rate of 5 tons per acre. In consequence of its

steepness, some of the land on the farm is difficult to cart, and the

liming of such land was no easy task. Mr M'Queen says:—"At first,

without knowing what results to expect, I limed several fields of old

cropped land, poor, wet, and out of condition, and I might have as well

put the lime down the river; it did no good whatever." A large dairy

herd is kept on the farm, to which I will afterwards refer.

In 1881 Mr J. S. Howatson entered the farm of Ramsay-cleuch,

of which the total rental is £400. Being essentially a sheep farm, no

crops are raised, but it is well drained and fairly fenced. The stock

consists of Cheviot sheep, from which the clip obtained last year was 4½

lbs. per sheep. Mr Howatson clips his sheep about the beginning of July,

and dips them in October.

Another extensive upland holding is tenanted by Mr

James Grieve. West Buccleuch is nearly all hill pasture, and extends to

about 3100 acres. The rental per acre is 5s., which is nearly 18 per

cent. higher than that of 1858. Within the past twenty-five years the

land has been more closely drained than previously, the expense of which

was mutually borne by the landlord and tenant. Enclosed land is all

tile-drained, but pasture without the fence is dried by surface or

"sheep" drains. About 2000 Cheviot sheep are kept on the holding, while

a few cross calves are bred and sent down to Fairnalee, in the parish of

Galashiels—occupied by Mr James Greive, junior—to be fed off as two-year

olds. Mr Grieve says:—"The system of farming in the Ettrick district has

undergone no change since 1858. The land is better surface-drained,

however, and sheep are better provided with hay and stells during

storms, but I think more might be done in the way of feeding sheep with

artificial food in storms and during bleak cold springs."

The farm of Nether Phahope, occupied by Mr Charles

Scott, is the highest in Selkirkshire but one. It is situated at the

extreme western corner of the county, and carries about 48 score of

sheep—at present one hirsel of Cheviots and the rest blackfaces and

crosses. Previous to 1854, the rental was about £250 ; from 1855 to

1865, the rent was £300; from 1865 to 1874, £360; and from 1874 to 1884,

£400. Last year the lease was renewed at a rental of £335. The farm

affords good summer grazing, but owing to its height the climate is cold

and stormy in winter. It is exclusively a sheep farm, and is rented at

about 7s. per sheep.

The farming customs and the prevailing*soil in the

parish of Kirkhope, which, previous to 1857 formed part of the parish of

Yarrow, so strongly resemble those of the Yarrow and Ettrick districts,

that no object can be served by entering into a description of

individual farms within its boundaries. It is mostly devoted to the

breeding and rearing of sheep, and is less extensively cropped than it

was some years ago.

The Selkirkshire estate of His Grace the Duke of

Buccleuch lies within the parishes of Selkirk, Kirkhope, Yarrow,