with the

water, which in a very few years completely fills them up.

The loam occurs in spots throughout the whole county,

and next to the rock soils of the eastern division is perhaps the most

useful.

The clay is mostly in the eastern side, in the

neighbourhood of the Cree and Wigtown Bay, though small portions are to

be found throughout the whole county. This is now looked on as being the

very worst soil an arable farm can consist of, as there is scarcely a

possibility of growing green crop on it, which is now so indispensable.

Improved moss now covers a good portion; and though

expensive to break up at first, in most instances is now

a very useful soil. The black-top is mostly reclaimed from moor, and in

many instances, where it has a clay subsoil, has proved very productive,

more especially for oats and turnips. Grasses and clovers are apt, in a

hard frosty winter, to be cut out of root.

Owing to the position of the county the climate is

very mild and moist. This mildness is accounted for by it having so much

sea-board, and the sea surrounding it being in direct connection with

the Gulf Stream; indeed such an effect has this on the western side,

that when snow-storms and frost prevail throughout the rest of the

country, little is known of them save what may be seen in the daily

papers. So much has this been the case that turnips are, or till within

these few years were, scarcely ever stored to any extent, but the

winters of 1878-79 and 1880-81 being so severe, that necessary work has

been much more attended to. The rainfall is also much greater than on

the east side of Scotland, as the subjoined will show, being the

rainfall for twelve months at each place,—East Linton 24.76, Dundee

31.90, Ardwell 39.40. The rainfall at Ardwell has been kindly

supplied by M. J. Stewart, Esq.

Owing to this moisture at all times of the year, but

more particularly in autumn, great difficulty is often experienced in

getting grain harvested in good condition, especially in the later

districts of the county. Heavy dews also often prevent a beginning of

operations for two or three hours in the morning.

The frequent great rainfall in summer is against the

proper filling and ripening of wheat and barley, the latter being often

of a very high colour; so much is this the case that latterly both these

cereals have in a great many cases given way to oats, which suit better

the moist climate. The prevailing winds are from the south, south-west,

west, and north-west; the trees on the west coast, where they do grow,

showing this very forcibly, being sloped up from the west side as if

annually dressed by a pruning knife, this being the effect of the spray

carried by the wind from the sea.

Retrospective State of Agriculture.

Wigtownshire being so far from the great centres of

industry, was for long more backward in its agriculture than the

counties more favourably situated in regard to markets. From the middle

to the end of last century prices were very low for agricultural

produce. Very low rents were paid in kind, wages also were very low; but

low as both these were, the farmers had great difficulty in meeting

their engagements.

About the beginning of this century an impetus was

given to agriculture owing to the French war, prices of produce being

very much enhanced. Money became more plentiful, and payments were now

made in money instead of in kind, as formerly.

But again, on the peace in 1815, a period of great

depression followed, and improvements which had been begun were not

carried out, and no new ones begun. But coming to the period with which

we have more immediately to deal, within the last twenty or thirty

years, very great improvements have been made.

Land which was thought to be irreclaimable bog or

moss is now bearing crops of all descriptions; and hillsides which were

covered with whins, rushes, or heather, are now covered with flocks and

herds. Dairy farming, which was introduced to the Rhins about the

beginning of the present century, has done much to cause an influx of

money, as the climate seems specially adapted for the manufacture of

cheese; and lands which, even though improved, might not be capable of

making any quantity of beef or mutton, carry a great number of cows,

which produce almost as much and as good cheese as they will do on the

better class of soils. Were it not for this fact, a great proportion of

the Rhins would still be as nature left it.

The eastern division of the county, being much more

fertile, was improved before the Rhins. It had been in a great measure

drained, fenced, and housed previous to much being done in this way in

the Rhins, though a great deal has been improved within the last

twenty-five years, as may be known by the large amount of money which

has been expended on the following estates.

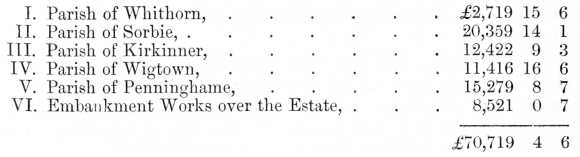

On the Galloway estates under the management of Mr

James Drew, there has been spent by the landlord from 1st November 1867

to 31st December 1882, the large sum of £70,719, 4s. 6d.

The late Sir John M'Taggart, who had got Ardwell

estates in a bad plight, stone-drained, fenced, and housed them more

than thirty years ago; so that within the scope of this report less has

been required to be spent than on some of the others, on which less had

been done, up to this time.

On the Earl of Stair's estates, managed by Mr T. C.

Greig, perhaps as much has been spent within the last twenty-five years

as on almost any estate in Scotland. Thousands of acres have been

drained, fences put up, with stones where available, and in others sunk

fences with hedges, or hedges on the flat,— these hedges being kept in

order by the proprietor—roads made, and farm buildings erected, to the

amount of £260,000. These improvements have not been carried out in any

special part of the estate, but over the whole generally. On one farm

alone on this estate, within the last fourteen years, the landlord has

spent between £5000 and £6000. The steading has been mostly rebuilt, the

whole drained, and stone fences put up; besides this, the tenant has

spent a very large sum himself.

The late Colonel M'Douall of Logan did a great many

improvements in Kirkmaiden. He kept his home farm of Logan mains in his

own hand, which was ably superintended by Mr Jamieson, now tenant of

High Curghie; and on it, under his management, a great quantity of moss

was reclaimed. But not content with this, he also took up the farms of

Inshanks and Garrochtrie, which were both drained, fenced, and housed,

and made ready for tenants to step into. Both were let to tenants after

being thoroughly improved; and each kept about one hundred cows. Besides

these, almost every farm on Logan estate has been more or less improved.

One thing the late colonel wished to see was all his tenants having good

dairy accommodation, he being a great enthusiast in cheese making. He no

doubt saw clearly that this was to be the sheet anchor of arable farming

in the Rhins.

Mr David Frederick, tenant of two or three large

farms on Ardwell estate, purchased, some eighteen years ago, the farm of

Gass in the parish of Newluce, containing about 1000 acres, the greater

portion of which was moorland; of this he has reclaimed about 300 acres

at a cost of about £10,000. He first drained, then ploughed and sowed

with oats, then green cropped, manuring and liming very heavily, eating

the green crop on the ground, with large supplies of cake, then sowed

down without a crop.

He has during this last year sowed between 60 and 70

acres with Timothy, from which he expects to cut annually 4 to 5 tons of

hay per acre. Though only sown in spring, he has this year cut from it 1

ton per acre. He has a steading almost finished which will hold over one

hundred head of cattle. It is used at present as a feeder to his dairy

farms; the necessary queys for keeping up the stock being grazed on it,

and cross bred lambs reared on it which are fed off on his dairy farms.

About 60 acres Scots of moss on the farms held by the

writer and his father have been reclaimed within the last thirty years.

The moss is very little above sea level, consequently a natural waterway

or burn which runs through part of this moss, and enters the sea about 2

miles from it, had to be deepened; and has now to be kept regularly

scoured in order to give an outlet for the drains. An open cut has been

made about 10 to 12 feet deep, at an acute angle to the burn, in order

to run as nearly through the centre of the moss as possible; and

parallel to this main drains have been cut at 18 feet distance, with

openings at intervals into the main cut, into which the furrow drains

are run. The main drains are laid with 4 to 6 inch horse-shoe tiles on

slate or tile soles; the furrow drains with 3 inch horseshoe tiles with

similar soles. Part of this improvement was done by the proprietor, Mr

Maitland of Balgreggan, the tenants paying interest. The other part, the

tenant did the workmanship and the landlord supplied the tiles. The cost

per Scotch acre of this operation was about £6.

Where the fall of the moss allowed, these drains were

cut 4 feet deep; but in some cases the moss had been cut too deep to

allow of this, the drains thus requiring to be cut at less depth in

those places. The moss gradually subsided after the first draining, so

that the first made drains had got to within less than 2 feet of the

surface; but, by deepening the burn and main cut, almost the whole has

been redrained to its original depth. The method pursued after draining

was to plough as lightly as possible and get harrowed, plough again and

harrow; and, if there was time to spare, to give a heavy top dressing of

gravel or till, a good dose, about four to five tons of lime per acre,

then plant potatoes on dung for two or three years in succession, after

which oats and potatoes were taken alternately. This moss is now wrought

under the regular six course rotation. It grows oats, potatoes, yellow

turnips, cabbage, and mangold, and lies the usual three years in pasture

grass. About 100 acres in the parish of Inch, known as Auchrochar moss,

was reclaimed some years ago by the Earl of Stair; in this case a drain

had to be built a good part of the way from the sea, as it ran through

running sand, and could not have been otherwise kept open. This moss was

wrought similarly to the one above mentioned, and is now also growing

the above mentioned crops.

A moss at Galdenoch, Leswalt, of about 100 acres,

owned by Sir Andrew Agnew, has also been improved; but it is worse to

keep dry than the others, a hard band intervening between the moss and a

sandy subsoil. This moss is now all laid down in pasture, after

undergoing somewhat similar treatment to the others. Owing to the great

difficulty experienced in keeping it dry crops are not easily raised,

nor when raised can they be easily taken off; as, when that times

arrives, the wet season has set in. About 20 acres of this moss have

been sown out, within the last two years, with grass and clovers after

potatoes heavily manured and limed without a white crop, which has

enabled it to keep more than double quantity of stock as yet. These are

only a few examples of what has been done in Moss-land ; there being

hundreds of acres throughout the district on different estates which

have undergone similar improvement.

The rotations now practised are the five, six, and

seven course system, viz., (1) oats, (2) green crop, (3) wheat, barley,

or oats, and then two, three, or four years grass; in some cases the

first year mown, but not in dairy districts. The most general course is

the six; as it is found by so dividing the farm that the same quantity

of stock can be supported during winter as is kept in summer. This is a

great consideration, as Wigtownshire is essentially a stock county;

besides it was found when the five course was pursued that turnips could

not be successfully cultivated, the frequent cropping causing a great

amount of finger and toe. It is only on a few farms of larger size that

the seven course is followed; but where it can be done, the turnips and

white crops both succeed better.

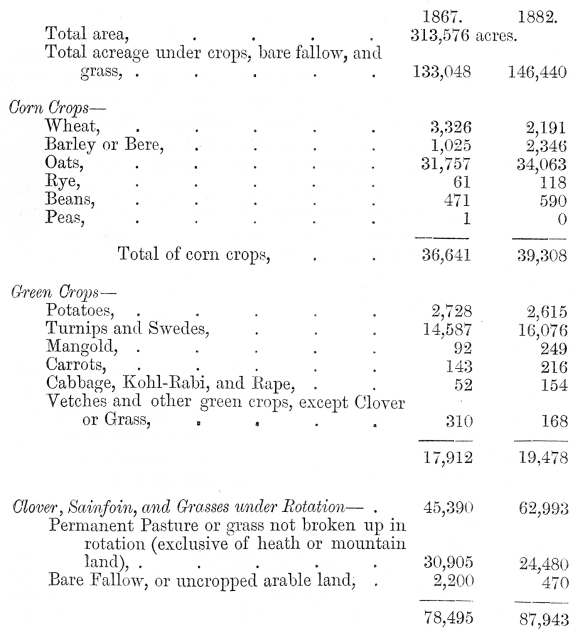

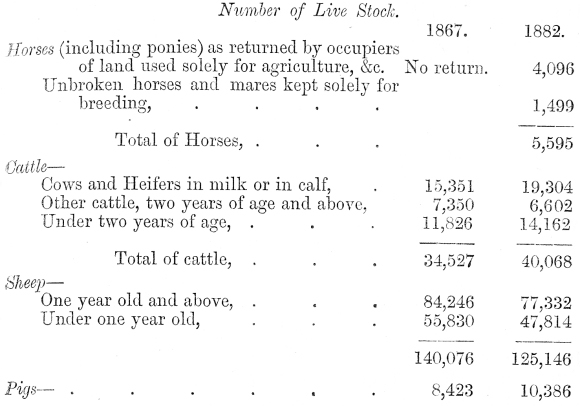

Board of Trade Returns for Wigtownshire.

Oats are sown on the lea break, which has been

ploughed during winter and after green crop. They are begun to be sown

about the 1st of March, and from that time all through that month and

the month of April, some being sown as late as the 1st of May where

sheep have been feeding on turnips. In a great many cases now where

there is moss or very heavy loam, it is the practice to get the turnips

lifted or eaten off before the 1st of February, in order to get the oats

ploughed in at that time. Where this is done it is found that the crop

is not so liable to lodge.

If the fodder could be dispensed with, sowing out

without a crop in such soils would be much more generally resorted to.

It is found that better quality of grain can be grown

from early sowing, though a greater bulk of straw and more grain can

often be got by sowing later. The first week of April is the time, if

the weather be suitable, when most oats are sown. Sowing by hand used to

be the only method; but within the last twelve or fourteen years

drilling machines have come very much into use. Where a proper tilth can

be got the drill makes a good job, but a great many are again sowing the

lea land broadcast, as it is found very difficult to procure a

sufficient tilth for the drill; but after green crop, where this can be

easily got, the machine is very widely used. The quantity of seed sown

broadcast is generally about 6 bushels per Scotch acre, and when the

drill is used from 3 to 4½ bushels,

according to the quality of the soil.

A great many different varieties are sown, each

farmer having his favourite. Potato oats deservedly stand high in the

estimation of many. Where the soil is fair and in good condition no oat

that has been tried can equal it for yield of grain. A great many dairy

farmers do not sow it on account of the smaller quantity of the straw,

this being a great consideration where a large dairy stock is kept.

Potato has also been found to yield better from bogs that are apt to

lodge than most other varieties, one cause of this is that it can be cut

greener, and while there is more sap in the straw; consequently it is

not so apt to be flatly laid, and is easier lifted, and the grain better

preserved; of course a great assistance to this is the early sowing

spoken of. The weight per bushel of this variety is from 40 to 45 lbs.

Sandy is a favourite in the more exposed and poorer

soils, and also for growing after green crop. It grows more straw, and

is not so liable to shake as potato; but the yield of grain is much

less. So much is this the case that we have heard a farmer,, who has

kept a very accurate account state, that had he grown Sandy oats, he

could not have held his farm. It is a greater favourite with millers

than potato, as it is very thin in the hull; it weighs from 39 to 43

lbs. per bushel. Another oat that has been widely sown lately and is

highly spoken of is Hamilton. It is more like potato than Sandy, has a

stiff short straw, and grows a white plump sample; it is said to be good

for heavy land, not being apt to lodge.

Early Angus, Longfellow, Birley, Canadian, and black

oats used to be pretty much sown; but now not to any extent.

The seed requires frequent changes, as if grown too

long on one class of soil it deteriorates in both quantity and quality.

The writer has found seed from Forfarshire to make a good change. A good

deal of seed is brought in annually from the Lothians, which succeeds

admirably.

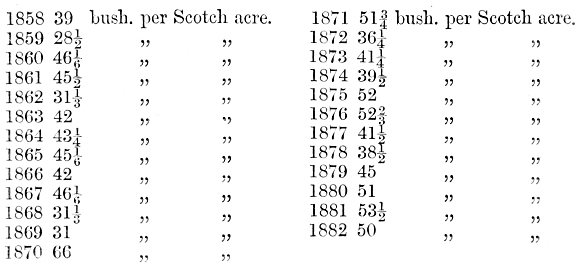

The average yield is rather difficult to get at, in

some districts it will be as high as 66 bushels per Scotch acre, and on

some farms even higher, while in others from 30 to 42 bushels is the

average; but we should say, take the county as a whole, from 42 to 46

bushels will be pretty near the average. We append the average of one

farm of 350 acres for the last twenty-five years.

Wheat—The acreage of this cereal is now very much

reduced In the county. It is grown on the strong soils in the eastern

division after a fallow, and on some of the earlier and lighter soils

after turnips; the reason of it being grown on these latter is in a

great measure owing to the greater quantity of fodder which it produces,

oats or barley on these soils growing very short straw, and quantity

rather than quality of this is sought. On the heavier soils fair crops

are grown, averaging in good years 40 to 45 bushels per acre, but on the

lighter soils from 22 to 33 bushels per Scotch acre may be taken as a

fair average, this with wheat at from 4s. 6d. to 5s. per bushel and the

risk of even less produce and a smaller price in a moist season is not

very encouraging for the growth of this cereal. The usual times of

sowing are, after fallow, on the heavier soils, in September or October,

and on the lighter soils after green crop during the whole winter, when

the weather is suitable as late as the middle of March, the quantities

sown varying from 3 bushels to 4 bushels per Scotch acre. The varieties

are red square head which is perhaps the heaviest cropper, but is not

considered so good for a wet season, Archer's prolific, Hunter's white,

and Uxbridge white, a little awny. Wheat is also sown later in spring on

some farms; this on the heavier class of black-topped soil often yields

a good crop of from 40 to 50 bushels per Scotch acre.

Barley.—This cereal is now more sown within the

last ten years; it is occasionally taken after lea, but principally

after green crop on the more friable class of soils. As previously

mentioned, owing to the moistness of the climate, barley cannot be grown

the bright clear colour so greatly prized. It is now grown by a great

many for feeding purposes. Most farmers who have their threshing mills

driven by steam or water-power having a grist mill attached; so that if

grain is cheap, or damaged in any way, they can break it and use it for

feeding stock; a great quantity of the barley grown in the district

being utilized in this way. It will yield from 32 to 52 bushels per

Scotch acre; the quantity sown varies from 3 to 4½

bushels per Scotch acre. The varieties sown are Chevalier and common

Scotch barley. It is generally sown on a newly ploughed or moist furrow,

as it requires a good deal of moisture to cause it to germinate

properly.

Beans are not much grown except on the clay lands

along the Cree.

Reaping Machines.

Reaping machines are now almost universally used for

cutting down the grain. A great many varieties of these useful

implements are in use, each farmer having his favourite maker. Some

prefer a side delivery, some a back delivery, but the great majority

work still with the manual delivery; the reason for this being that

there is less machinery; consequently the draught is lighter and there

is less chance of breakage, and a boy extra drives the horses. Each

machine will take, when cutting one way in an ordinary crop, from seven

to nine people to attend it according as they happen to be men or women.

In this way from 5 to 6 Scotch acres can be cut each day. In some cases

the machine is sent round the field, or a cut made through the standing

grain, the machine cutting up one side and down another. From 8 to 10

acres may be cut, but this can only be managed in a standing crop and in

moderate weather; the usual practice on large farms being for two

machines to cut one way, the one following the other. This suits best on

most farms, as there is very often some part of the field laid, and care

is taken to cut as fair against the lay of the grain as possible.

The self-binder has not yet found its way into

Wigtownshire; but we know of one farmer (Mr Chalmers, Freugh) who had

one ordered for this season, but owing to press of work the maker could

not supply him in time; we believe that he will have it ready for work

before next harvest. The grain is all bound up after the machines and

set up in stooks from six to ten sheaves. It is then allowed to sit till

ready for stacking, which in some harvests, such as the late one has

been, is rather' a precarious operation. If the weather be suitable

eight to twelve days may be sufficient; but, sometimes three to five

weeks may elapse before anything can be done. Some prefer stacking in

the field, either in round or oblong stacks, and carting home for

threshing during winter. This has one or two points to recommend it. The

grain is not all at one place, and in case of fire less damage is likely

to be done; it also can be more quickly stacked in unsettled weather. On

the other hand, it is not generally so neatly put up and therefore not

as safe, besides being often to cart long distances during bad weather

in winter time to the steading. The greater part is, however, carted to

the stackyard, where a seat has generally been specially prepared for

each stack, the prevailing shape of which is round; round stacks are

much easier finished, and present a neater appearance when finished.

During the damp weather in harvest thatch is made,

and when time allows straw ropes are also made; but should the harvest

prove dry, time is not taken for the latter process, " coir yarn" being

almost universally used for roping.

Horse threshing mills used to be very common; but

they are gradually being displaced by steam where water power is not

available. In some cases no mill is put up at all, and, instead of a

barn and straw house being built, merely a large straw house is put up,

and the whole threshing done by the travelling steam threshing machines.

These machines either belong to a joint stock company or private

individuals, and are drawn and driven by a traction engine; they have

also straw elevators attached, which greatly reduce the labour of

stacking the straw and where the large straw houses are, there is a hole

in the roof through which the elevators drop the straw into the centre

of the house. The charge for threshing with these mills is 4s. per hour

with 15s. for each shift, or 4s. 6d. per hour and no charge for

shifting. This latter is very suitable for smaller farms where there are

only a few hours' threshing at one time. The dividend paid by these

mills when in the hands of companies varies from 7 to 15 per cent.

As previously mentioned, a good deal of the inferior

grain is now used for stock feeding, being first passed through the

grist mill. The better class of grain goes to Glasgow, Carlisle, and

Liverpool, chiefly passing through the hands of local dealers.

Green Crops.

We now come to the principal crop of the rotation,

viz., the green crop, the preparation for which is begun immediately

after harvest. In the lighter soils in the Rhins, scarifying is at once

proceeded with. This is done either with the double furrow plough as

lightly as possible, drawn by two or three horses (we saw a three-furrow

scarifier for two horses, but have not yet seen it work), or the

ordinary four horse grubber, with specially prepared tines. Where the

grubber is used, the ground is usually gone over twice, the second

grubbing being at right angles to the first. This operation has to be

performed as lightly as possible, not more than two or three inches in

depth, as if done deeper it cannot be got so well harrowed, and in this

lies the whole success of the operation. As soon as the grubber or

plough has finished and the soil is thoroughly dry, the heavy iron

harrows, usually drawn by three horses, are passed over the ground two

or three times, a lighter set of harrows following, and passing twice

over it, often finished by one or two strokes of the chain harrow. The

ground is then drawn off into 15 or 18 feet ridges, and dung carted out

and spread; when the whole is ploughed down with a good deep furrow. In

other cases the dung is carted on to the stubble and ploughed down; and

in others the stubble is ploughed and the dung applied in the drill, or

on the removal of the green crop, and preceding the following white

crop. The application of dung in the drill is being more resorted to,

as it is found, though there is a good saving of labour in spring by

applying it in autumn, that there is less loss of the soluble

constituents in our porous subsoil by applying it nearer the time of

sowing the seed. Where dung is applied in drills it is the usual

practice to cart it into the field during frosty weather and put it up

in square heaps, drawing the horse and cart over it, thus preventing

fermentation and consequent waste. The land, after being ploughed deeply

in autumn, is allowed to lie in the furrow till dry weather suitable for

harrowing in the spring ; when two or three strokes of the heavy iron

harrow makes it ready for the grubber, which is generally passed through

at right angles to the autumn furrow ; and where scarifying has been

done this is generally sufficient to prepare the land for turnips or

potatoes. Where carrots are grown a cross ploughing generally precedes

the spring grubbing. Less couch is now gathered from the surface; as,

where any growth of such or other grasses natural to the soil takes

place, it is generally pretty well deadened by the autumn work; and if

any should turn up in spring, it is put into the drills and covered with

the manure, though in some cases gathering is still resorted to.

Potatoes.—Potatoes for the early market are the

first green crop which needs to be planted; a good many acres are now

planted on the lighter lands in the Rhins for the early Glasgow market.

Planting begins as early in February as the weather will allow. The

drills are drawn about 24 inches apart, a good dressing of dung applied

with 8 to 12 cwts. of the best Peruvian guano, or some specially

prepared potato manures, the potatoes being planted at intervals of

about 8 inches; the whole is then covered by the drill plough. The

drills are afterwards harrowed down with bow-shaped harrows which fit on

to the drills, and the drill plough is again put through them—this

operation being performed twice before the potatoes make their

appearance above ground—to keep down weeds and freshen the surface of

the soil. After they are fairly up, drill harrows and grubbers are kept

going to keep down the weeds between the drills, and hand-weeding is

done between the sets ; when ready for earthing up, this is not done so

deeply as with the later varieties, it being the great object during the

dry months to catch as much moisture as possible by having the drill

rather broad than sharp on the top. The mode of sale is usually by the

acre, from £17 to £30 per imperial acre being got for them according to

the earliness and kind of potato used. The buyer usually lifts the

crop—an operation which is generally begun about the beginning of July,

and is done by hand-digging. The favourite for the last two years has

been the Climax. It is said to come from ten days to a fortnight earlier

than most other varieties, and has a nice white dry flesh. Another which

treads closely on the Climax is Goodrich's, which is only a very little

later, and of equal quality. There are also Snowflakes, Redbog, Regent,

Pink Eye, and endless other varieties, each variety having some special

recommendation.

Rape is taken after the removal of this early crop,

and makes capital autumn food for sheep, besides keeping the land in

better condition, as it is no time without a crop; thus taking up the

nitrates which are continually forming in the soil, and which in our

porous subsoil would be otherwise likely washed away.

For later planting, the Champion and Magnum Bonum

have now all but displaced all other varieties, and deservedly so; as

they are both heavier croppers and much less liable to disease.

These later varieties are not planted to any great

extent, save in mosses or other softish land, where turnips do not bulb

so well. They are planted about the middle of April, and are ready for

lifting about the middle of October; which operation is done in many

cases by the potato digger.

Cabbages.—Cabbages are now grown to some extent

on the heavier class of loams and mosses, and are found very useful for

autumn food for lambs and shearlings, besides being the best autumn food

for milk cows. They will, where a good crop, feed twice as much as a

fair crop of turnips. The land is either dunged in autumn or the dung

applied in the drills in spring; being a gross feeder, they cannot be

overdone with manure. Being naturally a sea side plant, seaweed is very

beneficial, but where this cannot be got common salt should be applied

at the rate of about 3 to 4 cwts. per acre. The drills should not be

less than 30 inches apart, and the cabbages also 30 inches apart in the

drills, to ensure a good crop of the Drumhead variety, with which we are

most accustomed. After the manure has been applied in the drill-about 40

carts of dung and 8 to 12 cwts. of other manures per Scotch acre—the

drills are covered up, and the chain or bow harrow run over the drills,

which makes the process of dibbling •easier, two or three boys or girls

being employed to lay the plants at the requisite distances on the top

of the drill. Those who are entrusted with the dibbling follow, taking

care not to double the root of the plant when placing it in the hole,

and pressing the point of the dibble down beside the root of the plant

on the outside of the hole, in order to give it a firm hold. After this

process all that is done is to run the drill grubbers and harrows

through, with hand-hoeing, to keep the weeds down, finally running the

soil up to near the necks of the cabbages. These, when planted early in

April (a damp time being always chosen for the operation), are ready for

use in the middle of September. The seed from which the plants are grown

is sown in August, and the plants allowed to grow through the winter,

being taken up in spring as required.

Carrots.—Carrots are now pretty

extensively grown on the

sandy soils, and, where not destroyed by wire-worm, have proved a

very remunerative crop. The land intended for carrots is generally cross

ploughed from the autumn furrow, grabbed till it is very fine and

thoroughly cleaned, great care being taken not to have any of those

operations done while the soil is the least damp; because, should there

be the slightest tendency to clogginess, the carrots are almost certain

to worm. The drills are drawn about 28 inches apart, and about 30 to 40

carts of well rotted dung applied with 12 to 16 cwts. of guano and bone

meal, or other manures. The drills are then well and deeply covered,

sowing being done by a machine which deposits two rows of seed about 6

inches apart on the one drill. They are generally sown as early in April

as the weather will permit. Great care requires to be taken about the

seed; as seed from two or three different firms at the same price on the

same farm have been known to give a difference of £10 per imperial acre

in the crop. With the two rows on the drill great care requires to be

taken in the working, the drill grubbers and harrows requiring to be set

very close. Hand weeding and thinning are necessarily very slow; but

when the crop turns out well, it repays any extra outlay for working.

The total work by hand will cost about 30s. per imperial acre. The crop

is sometimes sold per ton, and sometimes per acre; when the latter is

done, from £24 to £34 per imperial acre is got, the average being about

£28. These carrots go chiefly to Glasgow, the finer to the bazaar for

culinary purposes, and the rougher for horse feeding. The usual time for

lifting is the end of October and beginning of November.

Mangolds.—Mangolds are also grown to some extent;

the soil is prepared similar to that for carrots. It is also manured

similarly, and the seed sown about the end of April at the rate of about

8 to 12 lbs. per Scotch acre. They have been very successfully

cultivated on light gravelly and sandy land on the sea shore by a very

liberal application of seaweed, and, sown on the same land year after

year, are still producing big crops of over 30 tons per Scotch acre.

They are taken up about the end of October or beginning of November, and

stored in pits with no other covering than a good spadeful of earth,

unless during frost, when some roughness is thrown over the pits to

prevent it penetrating. They are very useful for spring food, when the

season of turnips is past, but are more used for feeding cattle than

dairy cows, as it has been found difficult to make a fine quality of

cheese when mangolds are used.

Turnips and Swedes.—We now come to turnips and

swedes, which occupy the great proportion of the green crop break. The

soil is prepared as previously mentioned; and if no dung is to be

applied, a liberal supply of about 10 cwts. of bone meal, with 2 cwts.

Peruvian guano, and perhaps 3 or 4 cwts. of superphosphates, are applied

per acre in drills, which are drawn from 26 inches to 28 inches apart;

these manures, having been previously mixed on the floor of some house,

are applied by hand. Machines were used some time ago in a few cases,

but they have been almost wholly thrown aside and the hand again

resorted to. The drills having been covered, the turnip sowing machine,

sowing two drills each time, then passes over them, depositing the seed

with a very light covering at the rate of from 2½

lbs. to 4½ lbs. per Scotch acre. The sowing

begins with May and is continued on till the middle of June.

When the turnips are well brairded, a drill grubber

drawn by one or two horses is used; after which Dickson's patent double

drill harrow passes twice through them, immediately before thinning.

This operation is done by women and boys at 1s. per day, who when

superintended can do them at from 3s. 6d. to 5s. 6d. per Scotch acre,

according to the freeness of the soil. Others again give from

¾d. to 1d. per 100 yards. As soon as the

singling is done the whole are again gone over, all weeds are taken out,

and any double plants singled.

Drill harrows and grubbers are kept going the whole

summer, as long as horses can go amongst them without breaking the shaws.

Yellow turnips begin to be used about the end of September; some give

them to the cows with the tops, but it is considered by many to be a

great cause of abortion, and has therefore fallen greatly out of use,

turnips of all kinds being generally topped and tailed before being

used. Feeding cattle also get this variety at this time. Sheep are also

folded on them early in October. The average cannot very easily be got

at; but possibly from 18 to 28 tons per acre will cover the majority of

'crops. Swedes are ready for use by the middle of November; they are

then lifted as good weather will allow, and carted home or stored in

some convenient spot to be easily got at when wanted. Until within these

few years storing was not very generally adopted, but a few hard winters

have made farmers think it rather risky to be without at least a part

stored. Some put them up in pits about 3 yards wide on the ground,

tapering to a point at the top, then cover with straw or other dry

material. Where seaweed of a grassy nature can be got it suits

admirably; as, with the salt it contains, it keeps the outside turnips

as fresh and sappy as those in the centre of the pit. Others again put

them up in squares about 2 feet deep, and occupying as much ground as

may be suitable for the spot selected; this, when the sides are

protected by a good spadeful of earth, and the top covered well with

straw, we think a very safe plan, as then the frosty winds cannot get

blowing through the pits—and it is generally those which do the greatest

damage—while, the top being open, any fermentation that might take place

is likely to be prevented. A very favourite plan in Dumfriesshire, which

is now being practised in this county, is running the single furrow

plough deeply between every alternate drill, pulling the drill on each

side of the furrow, dropping them neatly into it tail downwards ; when

the plough comes up on the opposite side throwing the furrow well over

the bulbs, which are thus protected from anything save a very severe

frost, while the growth is stopped for a time. Turnips so stored are

turned out very fresh in spring ; and if taken up during dry weather,

very little mould sticks to the bulbs unless the ground be of a clayey

nature. The plough requires to be used for turning them out of the

furrow again; but otherwise, they just require "snedding" like turnips

in the ordinary way. Another and simpler method is to run the turnips up

in the drills where they grow, with the ordinary drill plough. By this

method the bulbs are not so well protected; and should the season turn

out mild, the tops grow on the whole winter, which reduces much the

feeding qualities of the bulbs. An extensive cattle and sheep feeder

informed us that by this method any turnips slightly diseased keep

better than by any of the others; though of all these plans tried by the

writer, the Dumfriesshire method gave the freshest bulbs in spring, the

cows doing better and relishing them more than those saved by the other

means. We have also the testimony of a large sheep feeder that hoggs eat

more and thrive better on turnips saved in this way. The cost may be a

little more, this operation costing about 5s. per acre; but when this

small charge is set against the saving of food, the wonder is that it is

not practised to a greater extent. The average yield of this, as of

other crops, cannot easily be got at, as we hear of over 50 tons per

imperial acre; whilst we have seen them as low as 6 tons. The average in

an ordinary season may be from 16 to 24 tons.

As we noticed at the beginning, green crops are

really the principal crop of the rotation; as it is often remarked if

they fail the succeeding white crop is not so good, and the grass

following is also inferior. This, in some districts where sheep feeding

is followed, can be accounted for by fewer turnips being there to be

eaten on the ground; but it also occurs in dairy districts, where no

sheep-feeding takes place; and this in our opinion can only arise from

the land, having little cover of crop, allowing couch and other weeds to

take the place of what ought to be profitable crops.

Grass under Rotation.

This crop occupies nearly one half of the arable land

of this county. The other crops are in a measure preparatory for this;

the land being cleaned and manured thoroughly, the grasses are sown out

with the white crop succeeding the green crop. The usual grasses sown

are perennial rye grass, from 1½ to 2 bushels,

Italian rye grass from 1/8| to ¾ of a bushel,

a mixture of 6 to 10 lbs. alsyke, cow-grass, white, red, and yellow

clovers, and in some cases Timothy and cocksfoot with fescues are added,

per Scotch acre. The operation is performed either by hand or by a

machine 15 to 18 feet in width, which distributes the seed by means of

brushes. "Where wheat has been sown, the seeds are not sown till the

wheat plant is strong enough to bear the heavy iron harrow, which is

passed over the young wheat as soon as the grasses are sown, being

succeeded in a few days by the land roller. Where barley or oats have

been sown, the grasses are generally sown immediately afterwards, some

rolling the surface before sowing then brushing the seed in with a brush

prepared for the purpose, others sowing on the newly harrowed ground,

and passing a lighter iron or wooden harrow over it, then rolling all

down together. Some again merely roll the grasses in on the newly

harrowed ground; but to this we object very strongly, after testing it,

as at least one third of the grasses never appeared. Even the lighter

soils are very much improved for grazing purposes by a judicious

application of lime, especially where a dairy stock is kept. The cow

carrying a calf for nine months in the year, besides giving milk for ten

months or so, reduces the phosphates so very much that unless the ground

is enriched by frequent applications of phosphatic manures, together

with lime, the pastures very soon deteriorate. We have also heard a

practical cheese maker remark, that while the farm he was making cheese

on was undergoing a course of liming, he made better cheese than after

liming was stopped.

Grass in the dairy districts is universally pastured

during the whole time it may lie ; while, where cattle and sheep feeding

is pursued, at least a part of the first year's grass is made into hay,

in order to have hay in spring for the feeding cattle, and the aftermath

of clover for harvesting lambs.

In the Rhins district there is not a great extent of

permanent pasture, the great bulk of it being in the lower district,

where there are some very fine parks on which many fine cattle are

grazed.

A great deal of what used to be meadow land is now

broken up and wrought as arable, but there are still a great many acres

devoted to this purpose. Where these are, haymaking generally begins

from the middle to the end of July. It used always to be mown by the

scythes, but the mowing machine has in most instances supplanted this

method, and we think deservedly so, as it comes at a time of year when

the horses are not very busy; and a mowing machine, when properly

driven, will cut down as much as six or seven ordinary men. When cut,

the hay is tedded, either by machine or hand, as soon as possible, drawn

into rows by the hay rake and lapcoled, and again as soon as possible

drawn together by a large rake or drag of American invention, and put

into ricks, in which it is allowed to sit till considered ready for

stacking, when it is generally put into stacks of an oblong shape. This

hay makes fine wintering for young cattle with a pound or two of cake

daily, and a plentiful supply of water. It is also very valuable for

dairy cows in spring, as a good portion of the cake or meal usually

given at this season can be dispensed with without loss of produce. In

some instances, where meadows have been broken up, they have been found

not to suit working in a rotation, owing to the quality of soil—grain

lodging and green crop going too much to shaw—and are again laid down to

meadow. We know of a farmer who has about 15 acres of this quality,

which has been wrought in rotation for over twenty years, which he is

now in the process of laying down. In the first place an oat crop was

taken, then a cabbage crop, half of which has just been eaten by sheep

getting § lb. of a mixture of linseed cake and Indian corn per day. It

is now proposed to plough, harrow, and roll the land previous to sowing

it out with Timothy, cocksfoot, and Italian rye grass, without a white

crop. Some similar quality of land in this district, sown with Timothy,

yields large crops of hay annually.

Galloway Cattle.

We take these first, they being the native cattle of

the district. Though the breeding of them is now almost confined to the

eastern division of the county, only a very few being now bred in the

western division, from fifteen to twenty years ago three or four herds

were kept in Kirkcolm; but they then gave place to the Ayrshire. The

Earl of Stair and one or two others have still a few select animals, but

in the eastern division great numbers are kept; among the principal

breeders being the Earl of Galloway, Mr Routledge, Elrig, and Mr

MWhinnie, Airyolland. These cattle have been long a favourite with

English graziers and Smithfield butchers. Great numbers used to be

bought up by graziers from Norfolk and Suffolk, where they were finished

for the Smithfield market. They are black in colour and hornless, and

are very hardy; having a great quantity of long silky hair, they are

able to lie outside and thrive during the winter, when less hardy cattle

could scarcely subsist. This latter quality, together with being

hornless, have made them great favourites with American cattle breeders.

In the matter of colour and want of horns they are more prepotent than

any breed we have seen; as, no matter what breed or colour of animal may

be crossed by a Galloway bull, the progeny is almost certain to have

these characteristics of the breed.

Bulls of this breed are highly prized for crossing

with Ayrshire dairy cows; as for some years back animals of this cross

have been in great demand. Where pure bred animals are kept for feeding

purposes they make fine cattle. We saw some bullock stirks this year

bred and shown by Mr M'Whinnie, Airyolland which were sold at £25 each.

They were the finest cattle of this age we ever remember seeing. The

demand from America has enhanced the price of breeding animals as much

as 100 to 150 per cent.

Great numbers of these pure and cross-bred cattle are

sold annually at Newton-Stewart by the Messrs Welsh, through whose hands

the majority of commercial cattle of the breed pass.

Ayrshires.

The Ayrshire cow has now in the western division of

the county almost wholly displaced the original Galloway, this being

owing to the suitableness of the climate and soil for dairy farming, and

the Ayrshire cow having been found much more suitable for this purpose.

These cattle were introduced into the county about the beginning of the

present century, and have gradually increased till they may now be

considered the breed of the district. Though, in the eastern division,

it was long before they found their way, they are now yearly

becoming-more numerous, as a change of tenant often brings this change

of stock; besides the older class of farmers are gradually working into

the dairying system. A good many of these cows are bred in the district,

chiefly on farms which have some portion of rough pasture which is used

for grazing for the young stock. But even on entirely arable farms some

very successful breeding stocks are kept, such as at Auchtralure, a herd

which is known all the world over where Ayrshires are kept. The great

proportion, however, of these cows are bred in Ayrshire, where they are

bought up till between two or three years of age; when the heifers,

which are then in calf, are bought by the dairy farmers either direct

from the breeders or through dealers. A great many are also annually

sold by auction at Stranraer, the price at this time being from

£11 to £15, these transactions being begun about the end of September

and carried on through the winter and spring months. The autumn months

are preferred for buying; as then the dairy farmer can winter the heifer

as he thinks will best suit his purpose. But there are always mishaps

occurring either through slipping calf, death, or other unforeseen

occurrences, which necessitate buying in the spring months, the price

then varying from £13 to £19. The usual practice with the calves of

these cows is to sell them all for slaughter as soon as dropped, except

the few which may be kept as above mentioned, or in cases where

Galloway, shorthorn, or polled Angus bulls are kept. The calves of

these, when not kept by the breeder, going to stock-raising farmers,

some of whom keep a few cows in order to rear calves. These cross-bred

calves within the last few years have been in great demand, as, owing to

the prevalence of disease, and the restrictions which are necessarily

imposed during its existence, Irish cattle, which were very much

depended on as a supply, have not been easily got.

When young Ayrshires are reared for dairy purposes,

the bull is put to the queys in the second summer, so that they come to

milk when three years old; though a good few have been feeding their

calves with cake and corn in order to get them strong enough to take the

bull as stirks; in this case they come to milk a year earlier.

Crosses and Cattle Feeding.

The cattle used for feeding purposes are mostly

crosses, which are bred chiefly in Ireland, and are brought across by

dealers, when they are bought by feeders at the usual monthly markets at

Stranraer, Newton-Stewart, and Wigtown. These cattle are mostly bred

from cross or native bred cows and shorthorn bulls:. and when well bred

are good quick feeders. They are generally bought in as stirks; are then

grazed, wintered on turnips and straw, with an outrun each day, and

shedded at night, grazed again, and finished for the fat market the next

winter; some feeders having them prepared for this purpose by giving

them 3 to 5 lbs. of cake on the grass previous to tying up. When tied in

they get about 1½ cwt. of sliced turnips each

day, these being divided into 3 feeds with 4 to 5 lbs. of cake, which is

gradually increased as they approach maturity till 8 to 10 lbs. are

given. Pulping the turnips has been tried by a good many of the best

feeders; but we do not know of a case where it has been continued.

In many instances, through more liberal treatment

(when young), they are finished at, or before, two years old; but in

this case they require to get cake from the time they are taken from the

milk till they are finished. We know a farm where for two or three years

twenty to thirty calves have been kept, part being after a shorthorn and

part after a polled Angus bull, and from Ayrshire cows, which are fed

off when fifteen to sixteen months old. The calves get new milk for a

week or two at first, then skimmed milk and a mixture of linseed and oat

meal boiled together till they are able to eat cake, when they get a

daily

supply of whey, with 2 lbs. of linseed cake, with

mangold cut by a sheep-cutter and hay or straw, till grass comes, when

they get as much cut grass as they can consume. This treatment is

continued during summer, more cake being given as the calves get older,

and vetches or cabbages taking the place of part of the grass as the

season advances. By the middle of October turnips and straw are

substituted for the grass; during winter they get about

¾ cwt. of turnips to each beast, with cut oats

or barley, besides the cake, as spring advances. In the end of April

mangolds and hay take the place of turnips and straw, and these again

are replaced by grass as soon in May as it can be ready for cutting;

they are usually sold about the end of May or beginning of June at from

£14 to £16 each. They are fed in outside courts (twelve in each court),

with sheds to lie in. The chief end in view is to make as much clung as

possible, to make up for the great annual waste which takes place

through the keeping of dairy cows. A few are fed in boxes; and last

year, the lot being sold by auction, one of those so fed brought about

£8 more than the average price; this showing what an advantage there

would be if the courts were all covered in; besides the manure is very

much superior when made under cover.

Where pure or cross bred Galloways are fed, they are

not usually tied up, being either fattened in boxes or wintered in

sheds, and fed off the grass with cake.

Sheep.

On the pastoral and moorland farms blackfaced ewes

are mostly kept, which are partly used for rearing pure bred blackfaced

lambs, and partly crosses from Leicester or other long-woolled rams.

Where pure blackfaces are kept, rams are procured at the annual sales at

Ayr or Edinburgh, besides those which are annually bred in the district;

the rams being put to the ewes from the 1st to the 20th November. The

wether and second ewe lambs, when ready for weaning, have either been

sold previously by character, or are taken to the annual lamb market at

Lanark, the top ewe lambs being kept in the stock for breeding purposes.

The cast ewes go chiefly for rearing crosses, generally to some of the

arable farms. They are put to ram early and

rear lambs fit for the fat market, which being sold early in summer,

allow the ewes themselves to get fit for the butcher before the season

is past. On most farms where such stocks are kept, wintering out has to

be resorted to for the stock ewe lambs. This is not so easily got now as

formerly, arable farmers being very unwilling to have these running over

their grass, when spring sets in, as they are not removed home till

about 1st April.

In some cases these lambs get a few turnips in

spring; but when good grass wintering is procurable, it is preferred.

The cost for such wintering will be from 7s. to 9s. each.

Few of what are known as national prize taking stocks

are in the district, though the sheep are generally of a high class. The

Earl of Stair has within the last few years taken a great many prizes at

both local and national shows, and we believe his stock is now as good

as can be found anywhere.

Crossing was carried too far during the inflated

times, unsuitable land being put to this use, and the stock of ewes so

much increased in some cases that nothing but failure could result. This

brought its own cure when the bad times set in, and many have now

returned to the blackfaces, with we believe greater profit to

themselves, and the result that better cross lambs are now to be had for

feeding purposes. Where ewes for crossing purposes are kept, the stock

requires to be kept up either by buying in second ewe lambs from

blackfaced breeders or in some cases the younger ewes are put to

blackfaced rams for this purpose. Generally Leicester or long-woolled

rams of some kind are used; but in some cases Shropshires are also used,

these last being now favourites with many.

These rams are procured at annual sales at Castle

Douglas and Newton-Stewart, where large consignments are sent by

breeders from Yorkshire, Dumfriesshire, and the Stewartry; these rams

being often highly fed before being bought, require extra food when

taken home; and even then the death rate amongst them is often pretty

heavy. They are put to the ewes early in November, a ram being

considered enough for from forty to fifty ewes. The lambs are weaned

from the 12th to the end of August, and have generally been sold either

to dealers or direct to farmers, by character, before this time; the

cast ewes are now either sold for feeding or go direct to the fat

market. The diseases most prevalent among these stocks are braxy and

trembling, which need not here be further alluded to, seeing that the

Highland Society has made them the subject of a very exhaustive inquiry

and report. On these farms surface draining has been done to a great

extent, with the result that the grasses are improved and the death rate

reduced.

Clipping generally begins about the middle of June,

and is continued on till the first week in July, neighbouring herds

helping each other.

Dipping with prepared dips has now taken the place of

smearing and pouring. This operation takes place about the beginning of

October, when the cast ewes are being drawn off.

The herding on these farms is usually done by married

shepherds, who in some cases are allowed to keep cows, in others they

have entirely a money wage. On many of the arable farms breeding stocks

of Cheviot and half-bred ewes are kept; where this is done a few Cheviot

gimmers are generally bought every year to keep up the stocks, besides

some of the half-bred ewe lambs bred on the farm being also kept for

this purpose. The rams which have been procured in the same way as those

used for crossing with blackfaced ewes are put to the ewes from the

middle of October to the 1st of November. Ewes of this class are

generally wintered on the oldest and roughest pasture, with the addition

of turnips carted out and scattered on the pasture, either whole, or, in

some cases, a cart which has a turnip-cutter driven by gearing from the

wheels is driven through the field, thus dropping the cut turnips along

its route. In other cases the ewes are netted on the turnip break, and

allowed to eat what they require from the ground until the lambs begin

to arrive, which is generally about the middle of March, when, if there

is any spring, they are put on the young grass; but if this should not

be forward, they are put to the best old grass with a supply of turnips

added. The lambs of this class are generally weaned about the 1st of

August, and are kept going on the best grass or clover stubble during

the autumn months preparatory to being folded on the turnips.

The method of feeding sheep on turnips has undergone

a great change for the better within the last twenty years. The practice

used to be to net sheep of all classes on the growing turnips, and allow

them to eat what they could from the ground ; but now, this is never

done with lambs, and in very few cases with older sheep. The turnips are

carefully "sned " and carted into small heaps of from two to five carts

at regular intervals, cut by a sheep cutter and given in troughs. By

this means the droppings of the sheep are spread almost as regularly

over the field as if the growing turnips had been eaten on the ground,

and a great saving of turnips effected; as, in wet or frosty weather,

great proportion of the crop was wasted. A good many different classes

of sheep are annually fed on turnips; on dairy farms three-years-old

wethers are preferred, as they do not require to be bought in. till the

turnips are ready for them. This suits very well, as there is generally

no grass to spare for autumn feeding of lambs, which require to be

brought home in August; but on farms where a feeding stock or breeding

ewes are kept, the clover stubble after removal of the crop of hay is

generally kept for autumn feeding for lambs. The classes usually fed are

Cheviot or blackfaced three-years-old wethers, which are bought by

character at Inverness, privately, at the annual sales at Perth, or at

the Falkirk tryst in October, where great numbers are shown; shearling

cross, and half-bred hoggs, blackfaced and Cheviot ewes, and half-bred

and cross lambs. When brought to the feeding ground, these sheep are

always dipped, as driving and trucking are very apt to produce heat.

Some feeders have a great many more than are required to consume their

own surplus turnips, and thus require to take feeding for part of their

flock from such as have turnips to spare, and have no sheep to consume

them. When this is done, the party supplying the food requires to do all

the work connected with "snedding" and pitting turnips, and also keep

the shepherd, unless a special agreement to the contrary is made; the

owner of the sheep paying a stated rate per week for such keep. This

varies owing to the turnip crop and the kind of sheep which may be fed,

Cheviot wethers being charged highest and cross lambs least. More grain

and cake are now used in feeding than formerly, especially when the

sheep are fed at home, as, besides putting on more mutton, the

consumption of feeding stuffs goes to enrich the soil for future crops.

Old sheep begin by getting a daily supply of about ¼

lb. of oats, or oats and linseed cake mixed, this being gradually

increased until in some cases one pound is reached. Younger sheep do

not, unless intended for fat in January and February, get grain , until

the spring months, as they have been found, if kept on in dry weather in

spring, after being fed with grain during the winter, to go off

considerably. The quantity given to hoggets does not generally exceed

½ lb. each daily. Ryegrass hay is also very

much used for lambs, as they have been found to live better by having

always a supply of it (the death rate in hoggets on some farms being

very heavy). This is mostly given in racks which are filled daily, or as

often as required. A system of cutting the hay and mixing the grain

given amongst the hay chaff, the whole being sprinkled with water,

sweetened with molasses, and given after being slightly fermented, was

tried some years ago, but the majority of feeders have given this up,

and are again giving these foods separately. The older sheep begin to be

sent to the fat market about the beginning of December, the younger

following in the spring months. They are either bought up by local

dealers or sent direct to salesmen in Glasgow, Liverpool, London, &c.

The Messrs Welsh annually kill a great many hoggets, the carcases being

sent to London in vans fitted for the purpose. During the restrictions

this year live sheep could not be got into Ireland, where a great many

of the fat sheep annually go. Mr M'Geoch, an enterprising local dealer,

killed at home and got the carcases taken by the Stranraer and Larne

steamer, thus supplying the majority of

Belfast butchers during the spring months.

Horses.

The Clydesdale horse, [We

are indebted to the Clydesdale stud book for most of the particulars as

to the introduction of this breed into Wigtownshire.] introduced

about the beginning of the century, is almost looked upon as a native of

the district, the Wigtownshire-bred Clydesdales having a world - wide

fame. About fifty years ago the late Sir James Hay of Dunragit had a

breed of grey mares; Mr Whyte, then in Balyett, had also some of this

strain. Mr Agnew, Balscallock, had also a good stock, in particular a

horse owned by him named "Farmer" (292), of a very high class himself,

having good feet, nice oblique pasterns, clean thin bone with fine

quality of hair, a good broad head well set on a fine neck, broad

chested, and well backed and quartered, with perhaps a slight shortness

of rib. He left a good class of mares, which, when mated with Drumore

stock, produced some well-known horses; but the late Mr Anderson of

Drumore did more perhaps than any other man to forward the breeding of

this class of horses. Not content with what could be got at home, he

went to Mr Fulton of Sproulston, who was then a noted breeder, made a

tour through the principal breeders, buying from Mr Somerville of

Lampits a daughter of what is known as the "Lampits Mare." He also

bought a mare from Mr Young, Brownmuir, Lochwinnoch, which won the first

prize at the Highland Society's Show at Ayr in 1835.

Mr Anderson also bought at this time "Old Farmer"

(576), a horse which, before this, had made his mark. Some years later

he bought "Farmer" (284) from Mr M'Kean, which when mated with "Tibbie,"

daughter of "Robert Burns" (701) by "Old Farmer" (576) out of "Susie,"

resulted in the production of "Salmond's Champion" (737) and "Victor"

(892); the former of the two last mentioned being the sire of "Lochfergus

Champion" (449), from whom a great many prize-taking animals of the

present day have sprung. The produce of " Victor" (892) have proved even

more successful than those of his elder brother, from him being

descended such horses as "Macgregor," "Young Lord Lyon" (994), "Prince

Charlie" (629), "Boydston Boy" (111), "Cadder

Chief" (1601), "Malcolm of Glamis" (1757), "Victor Chief" (1855),

"Victor Chief (1856)," Master Lyon" (2282), and such mares as "Dora"

(115), "Jess" (355), "Dun-more Maggie" (87), "Garscadden Lovely" (40),

"Maggie" (41), "Flora" (59), &c, and through these of the most

fashionable blood of the day. Then we have "Rob Roy" (714), from whom

came "Hercules" (378), out of a mare by "Biggar" (45), a horse which

left a very good stamp of short-legged mares. "Hercules," whose blood

will be found in several of the best sires of the present day, is the

sire of "Lord Lyon" (589). This horse was out of "Puppet," an English

bred mare which had bred many winners of prizes in her native country

before being brought to Wigtownshire, she being also descended from a

prize-winning strain. "Lord Lyon," though not what is known as a pure

bred Clydesdale, when mated with "Victor" (892), "Glenlee" (363),

"General Williams" (326), and other such well-bred mares, has produced

more prize winners than any horse of modern times; such mares as "Young

Darling" (632), "Effie Deans," "Pollock's Darling," "Queen of Quality,"

"Alice Lee," "Mayflower," "Dolly Dutton," "Dandelion," "Eugenie,"

"Dido,"-—the champion yearling filly of this year (1883), out of "Mary

of Drumflower" (519), —and very many others being got by him. He also

sires a strong array of stallions; amongst others being "Young Lord

Lyon" (994), "Cetewayo" (1409), "Lord Colin Campbell" (1475), "Fitzlyon"

(1656), "Apollo" (1386), "Lucky Getter" (1483), "British Lyon," "Victor

Chief" (1856), "Master Lyon" (2282), these being only a few out of great

numbers got by him.

Another noted horse which treads closely on "Lord

Lyon" for fame is "Farmer" (286), bred by Mr P.Anderson Gillespie, being

got by "Merry Tom" (836), out of "Mary" by "Loch-fergus Champion "

(449). He has a double strain of Drumore blood. He has sired many

prize-winning stallions, amongst others "Disraeli" (234), "Dreadnought"

(241), "Druid" (1120), "Sir Colin" (777); the names of those horses

being familiar as household words to all Clydesdale breeders. The mares

after "Farmer" are now very much run after for breeding purposes ; any

one lucky enough to have them can scarcely be induced to part with them

except at a very high figure; amongst others he is the sire of the dam

of "Belted Knight" (1395), which, got by "Glenlee" (363), is considered

one of the best stamps of a Clydesdale stallion to be found.

"Clansman" (150) also did good service, before being

sent to Forfarshire, many good breeding mares being got by him as well

as the noted stallion "Thane of Glamis."

"Warrior" (902), was bought by Mr Thomas Kerr, Barr,

at Glasgow in 1875, where he had won the first prize in the

three-year-old colt class at the Highland Society's Show; and although a

good profit was offered the new owner, he very pluckily refused to part

with his purchase. This horse has done much to improve the breed of

mares in the Machars district, where he has been in use mostly since

that time.

Some years ago two horse breeding associations were

formed in the Machars for the purpose of bringing in stallions to

improve the breed of horses; these societies have done much towards this

end. Any one attending the annual show at Wigtown ten years ago, and

seeing the same show now, could not help being surprised at the advance

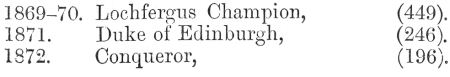

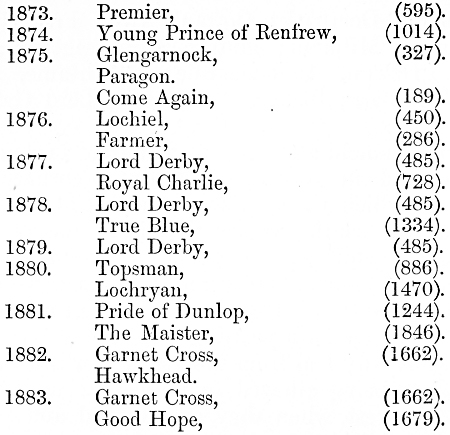

which has been made. The following horses have travelled the two

districts embraced by those societies:—

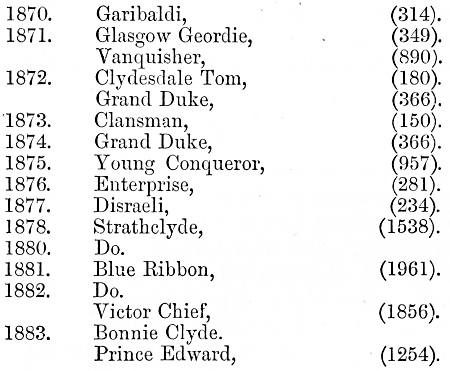

In the Rhins there is no such society as exists in

the Machars, but it has been the practice annually for a number of

farmers to band themselves together and elect two or three of their

number to select a horse, or sometimes two, to travel in the district;

the horses so selected have been as follows:—

Besides these the horses before mentioned, viz.,

"Lord Lyon," "Farmer," "Glenlee," "General Williams," "Prince Charlie"

(629), "Old Times" (579), "Belted Knight," and many others have done

good service. Enough has been said to show that Wigtownshire stands in

the very first rank as a Clydesdale horse-breeding county.

Amongst the present successful breeders of

Clydesdales in the county, are Messrs Milroy, Galdenoch; M'Dowall,

Auchtralure; M'Camon, Kirranrae; Cochran, North Cairn; M'William,

Craichmore; M'Kissock, Glaick; M'Master, Culhorn Mains; Rankin, Aird;

Dorman, Deerpark; Cowan, Aird; Frederick, Drum-flower; Ralston, Milmain;

Matthews, Carsegowan; M'Connel, Glasnick; M'Dowall, Auchengaillie;

M'Whinnie, Airyolland; Drew, Nether Barr; Picken, Barsalloch; Lord

Galloway, and many others.

Horse fairs are held annually at Stranraer in

January, June, and October, and in Newton-Stewart in February, June, and

November, at which the ordinary commercial class of horses change hands,

the south country dealers attending and buying them up. Good geldings

are now very scarce in the county, the great demand for breeding stock

for America causing few colts of good appearance to be castrated, the

price of a good five-year-old gelding being got for a yearling colt.

The mares usually foal from the 1st of April to the

middle of June, the foals being allowed to follow the mother until the

beginning of harvest, when they are weaned and put on good grass with

the addition of a little oats; after harvest some are put on to the

seeds and allowed to lie out all winter, getting a daily allowance of

oats, or other nutritious food; some put them into a cool box at night

and allow them to go out on old pasture during the day; they are then

allowed to pasture amongst the cattle during the next summer, and are

again treated in a similar manner during the next year, until the month

of October, when they are rising three years old. They are then brought

into the stable and wrought easily for a month or two before being put

to regular work.

Dairy Farming.

This, as previously mentioned, is a branch of:

farming for which Wigtownshire seems especially adapted, the rotation

which suits the soil allowing about the same quantity of stock to be

kept summer and winter. The Ayrshire cow is exclusively used as the milk

producer, the method of procuring which has been before specially

referred to. The number of cows kept in each dairy varies from 20 to

140, the most common size being from 60 to 80. These are managed in

three different ways, either being let to a bower; the management let to

a man with a family, who does the whole work connected with the cows and

dairy; or a man is kept to look after the cows and pigs, and a dairymaid

kept to do the work connected with the dairy alone. Where a bower is

kept, the farmer supplies food for the cows, the usual quantities being

one acre of yellow turnips for ten cows for autumn food, or an

equivalent in cabbage or cotton cake, 5 tons of swedes for each cow

during winter and spring, or if only three or four tons be given, bean

meal or cotton cake is given in lieu with the run of the straw for

fodder, and the addition of 140 lbs. of bean meal for each cow during

the spring months; in summer from 1 to 1½

acres grass is allowed for pasture for each cow, with, in some cases, an

acre or two of young grass or vetches which are given out during July

and August. The bower gives 20 stones, of 24 lbs. to each stone, of

cheese for each cow, and 16 to 17 stones for each

quey or picked calf cow; the cheese is generally to be made of a

quality equal to some other two dairies in the immediate neighbourhood;

sometimes a money rent is paid, but this being only in isolated cases,

we could not say what is the general rent in such instances, as if near

a town or railway station, they may be worth from £2 to £3 each more

than if in some remote district. The location of the farm seldom makes

much difference to the number of stones expected, as on poorer farms a

greater extent of grass is given, which is expected to make up for any

deficiency that may arise from the quality of the soil. As to the

quality of cheese, Mr Harding is credited with having said :—" Cheese is

made in the dairy; yonder, where A is feeding his kine on broad clover,

tares, or rye grass; or where B on the very edge of the moor is making

what was almost desert to blossom as the rose, with the varied arable

forage crops of a first year's cultivation; or yonder again, where C and

D are managing old land carse farms in the grooves first made

generations ago,—I will take the same milk from any of them, and make

the same cheese anywhere. Cheese is not made in the field, or in the

byre, or even in the cow, "it is made in the dairy."

The bower has the whole of the calves, which are

worth from 7s. to 9s. each, and the whole of the whey for pigs, which

may be worth from 25s. to 30s. for each cow; he has all materials, such

as cheese salt, rennet, colouring, cloths, &c., to supply, and pay for

milking, a number of women being generally kept on the farm for milking

and weeding; these milkers usually get 2s. per week each, the time

occupied in milking being from one to one and a half hours each time,

morning and evening, each milker having ten cows.

In the second instance where a man with his family is

employed to look after cows, pigs, &c, he is generally paid at the rate

of from 20s. to 25s. for each cow, with an allowance of one pennyworth

of milk daily, 2 to 3 lbs. butter per week, and 4 to 6 bushels potatoes

set; in some cases where a good cheesemaker has been for some time on a

farm he may get an allowance of flour or oatmeal extra with liberty to

keep a pig. In a few instances 1s. per stone for every stone of cheese

made is paid; in such a case it is for the interest of the maker to have

as many stones as possible, and the quantity may thus be increased. When

cows are managed in this way the farmer is at greater liberty in regard

to the food supplied, and more dairies are now managed in this way than

was the case some years ago; one reason for this being that a trade in

milk to the large towns during the winter and spring months has been

started. Where the third method is followed, a man with ordinary

ploughman's wages looks after the cows, &c., the dairymaid who makes the

cheese living in the farm house, and getting from £18 to £25 annually

with rations.

In almost all dairies within 4 or 5 miles, some even

8 miles, from a railway station, the milk is sold during five or six

months, beginning about 1st November and selling on to 1st April or 1st

May. Prices vary very much, so that an average is not easily arrived at;

the writer has sold at, for November and December, 8d.; January and

February, 9d.; March, 7½d.; and April, 6½d.

per imperial gallon, at the nearest railway station, the buyer supplying

the necessary vats for its conveyance by rail—a little more could have

been got had we supplied the vats ; this may perhaps be taken as being

as near an average as possible. The usual charge for conveying milk by

rail to Glasgow and northwards is 1d. per imperial gallon ; to Liverpool

and southwards l½d. per gallon. Owing to this