|

By James Tait, 4 Argyll Crescent, Joppa, Midlothian.

[Premium—Forty Sovereigns.]

The county of Lanark, sometimes designated

Clydesdale, is bounded on the east by the counties of West and Mid

Lothian and Peebles, on the south by the county of Dumfries, on the west

by the counties of Ayr and Renfrew, and on the north by those of

Dumbarton and Stirling. Its greatest length from north to south is about

47 miles, and its width from east to west about 32 miles. According to

the agricultural returns issued by the Board of Trade the area of the

county is 568,840 acres; and in extent of surface it is exceeded only by

those of Aberdeen, Argyll, Ayr, Dumfries, Inverness, Perth, Ross and

Cromarty, and Sutherland. Its gross annual value, exclusive of the

municipal borough of Glasgow, as given in the Return of Lands and

Heritages in Scotland, 1872-73, was £1,736,268,

7s., inclusive of Glasgow it was

£4,078,434, which is pretty

nearly thrice the valuation of any other Scottish county. The gross

annual value of Edinburghshire at the same date was £581,603, 6s.,

exclusive of Edinburgh and Leith; including these municipal boroughs the

total valuation of the county was £1,547,435. The next highest is

Perthshire, with a valuation of £959,364, 18s. In 1883-84 the valuation

of Lanarkshire was £2,211,444, 15s. 7d,, an increase of £66,991, 17s.

5d. on the previous year. The census returns for 1881 give the area of

Lanarkshire as 564,284 acres, divided into 41 parishes, besides

fractions of others. There were 180,259 inhabited houses, 193,731

separate families, and 904,412 inhabitants. Of the population 770,314

were resident in towns, 72,197 in villages, and 61,901 in

rural districts. The county contained 1076 persons to every square mile.

Next in density of population were the shires of Edinburgh and Dumfries

each containing 1075 persons to the square mile. Then conies Clackmannan

with 539. The lowest in the scale is Sutherland with 12 persons to the

square mile, and it is followed by Inverness with 22, Argyle 24, Ross

and Cromarty 25, and Peebles 39. The next county to Lanarkshire in

respect of population is Edinburgh, with an area of 231,724 acres, and a

population of 389,164. In 1S71 there were, in Lanarkshire, 147,962

inhabited houses, and 765,339 of a population. In 1861 the population

was 631,566, showing an increase of 272,846 in twenty years. For

parliamentary purposes the county consists of a northern and a southern

division, of which the former is at present represented by Sir T. E.

Colebrooke, Bart., and the latter by J. G. Hamilton, Esq., of Dalziell.

The city of Glasgow has three representatives; and, in the county, there

are the burghs of Rutherglen, which forms one of the Kilmarnock group,

and Airdrie, Hamilton, and Lanark, which are joined to Linlithgow and

Falkirk. For administrative purposes the county is divided into upper,

middle, and lower wards. The upper ward comprehends the twenty parishes

of Carluke, Lanark, Carstairs, Carnwath, Dunsyre, Dolphinton, Walston,

Biggar, Libberton, Lamington, Culter, Crawford, Crawfordjohn, Douglas,

Roberton, Symington, Covington, Pettinain, Carmichael, and Lesmahagow.

The middle ward includes the parishes of Dalserf, Stonehouse, Avon-dale,

Glassford, East Kilbride, Cambusnethan, Shotts, New and Old Monkland,

Hamilton, Bothwell, and Blantyre. The lower ward, lying immediately

around the city of Glasgow, contains Carmunnock, Cambuslang, Rutherglen,

Cadder, Govan, part of Cathcart, and the Barony parish.

Towns.

Glasgow is situated on both banks of the Clyde, in

the parishes of Barony and Govan, with a very small portion of Cathcart.

The Barony parish contains 14,926 acres, and Govan 6733; and the census

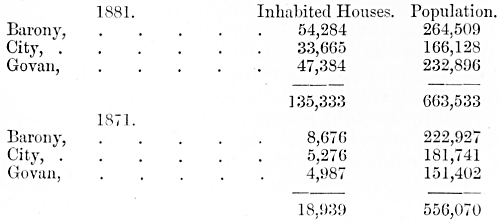

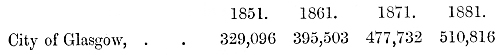

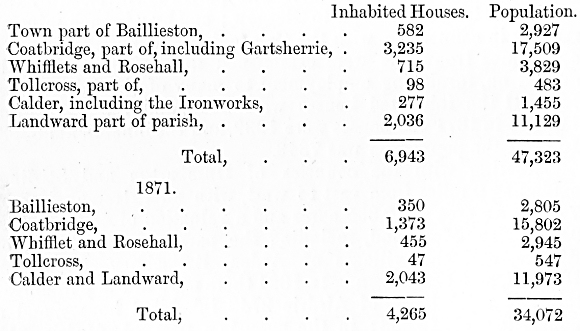

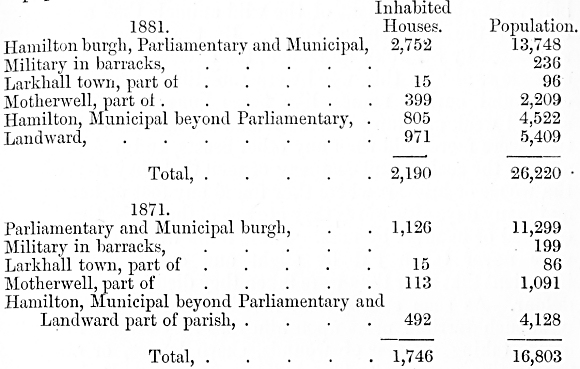

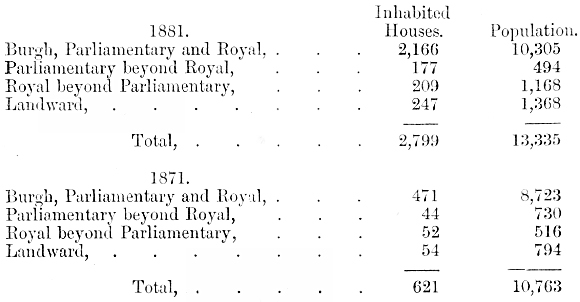

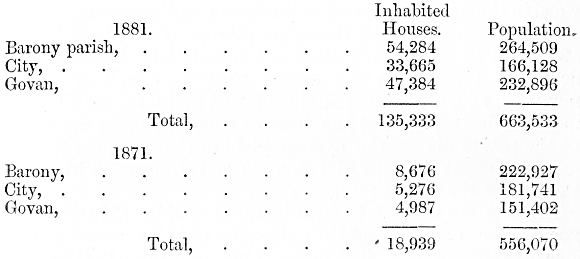

returns for the two parishes give the following results:—

These figures include the landward part of the

parishes, and the following give the population of the city for the past

thirty years.

The population of the registration districts was

491,846 in 1871, and 511,532 in 1881. The Barony parish includes the

districts of Maryhill, Shettleston, and Springburn, besides the Barony

proper. Maryhill is partly mineral, agricultural, and commercial. It

includes the town of Maryhill, peopled chiefly by work people, in the

different foundries. The locomotive works of the North British Railway

Company are situated at Cowlairs, in the Springburn district; and the

Saracen Foundry at Possil, equi-distant between Maryhill and Springburn,

employs a large number of hands. A new suburb of Glasgow has sprung up

here, called Possil Park. Military barracks were erected on the banks of

the Kelvin four or five years since; and in these palatial buildings,

Her Majesty's troops are quartered in the order of service. Maryhill was

erected into a police burgh in 1856, and has made rapid progress. The

population of the burgh was 3717 in 1861, in 1871 it was 6659, and in

1881 it had risen to 18,386. In the city portion of the parish, great

changes have been made during the past thirty years. Many old historic

buildings and streets have been removed. Twenty years ago it was found

to be necessary, in the interests of the public health, for the

corporation to purchase, demolish, and rearrange many streets in which

sanitary arrangements could not be carried out. To meet the demand for

house accommodation caused by these changes, new houses were built in

the suburbs. The railway system has tended to promote many changes. The

City Union Railway opened up the dingy quarters of the Briggate, where a

palatial railway station now stands. The Caledonian Railway Company, by

their new line across the river, have removed a once notable business

street. Gallowgate has been almost rebuilt, and the Stobcross Railway,

in the west end, opens up further possibilities of change in that

quarter. The towns in the Barony parish do not now appear distinct from

the city, and their final absorption into one great city under one

municipal authority is probably only a question of time. The parish of

Govan, situated on both sides of the Clyde, is notable for shipbuilding.

Two considerable towns have grown up within the past quarter of a

century, chiefly sustained by that industry. In 1851, the joint

population of Govan, on the south bank of the river, and Partick on the

north, was 3131; in 1861 the population of Govan alone was 7637; in 1871

it had risen to 19,899; and in 1881 to 51,783. In 1861 the population of

Partick was 8183; in 1871 it had risen to 23,837; and in 1881 to 38,985.

South of the Clyde, and on the borders of Renfrew-shire, are the

suburban districts of Pollokshields, Crossbill, Govanhill, and Langside,

which are chiefly inhabited by Glasgow business men. Public parks have

long been a feature of the city. The oldest is Glasgow Green, situated

to the east of the city, on the river banks. At the opposite end of

Glasgow is the West End Park, traversed by the Kelvin, overlooked by the

university, and ornamented with a fountain to commemorate the

introduction into the city of a water supply from Loch Katrine. The town

council have likewise acquired the Botanic Gardens, in the aristocratic

suburb of Billhead; and the Kibble Palace and Winter Garden are situated

there. The Alexandra Park is at the north-east corner of the city in the

Dennistoun district; and in the centre of Crosshill and Langside is the

South Side Park, the site of which is incomparably superior to any of

the others. It would be difficult if not impossible to describe in brief

compass the industries of Glasgow and the enterprise of its merchants,

all dependent more or less directly on the Clyde navigation, itself a

gigantic undertaking. In a paper read at the Naval and Marine

Engineering Exhibition, in 1881, Mr James Deas, C.E., described "the

character and magnitude of those works which have, within the last

hundred years or so, converted the Clyde between Glasgow and the sea

from a shallow stream, navigable only by fishing wherries of at most 4

or 5 feet draft, and fordable even 12 miles below Glasgow, to a great

channel of the sea, bearing on its waters the ships of all nations, and

of the deepest draft, bringing to this city of the west the fruits and

ores of Spain; the wines of Portugal and France; the palm oil and ivory

of Africa; the teas, spices, cotton, and jute of India; the teas of

China; the cotton, cattle, corn, flour, beef, timber,—even doors and

windows ready made,— and the numerous notions of America; the corn of

Egypt and Russia; the flour and wines of Hungary; the sugar, teak, and

mahogany of the West Indies; the wools and preserved meats and gold of

the Great Australian colonies; the food supplies of the sister isle; and

the thousands of other things which go to make up the imports of the two

mile-long harbour of Glasgow (which, until a few years ago, was simply

the river Clyde itself), lined on both sides with wharfs and quays, and

carrying away to India and our colonies—even to Fiji, and to every

foreign land—the varied products of this great city and the whole south

and west of Scotland, from the coal and iron of our mines to the finest

products of our looms and the most improved types of our varied

machinery." Eighty years ago the quayage of the harbour was only 382

lineal yards long, the area of the harbour 4 acres, the revenue of the

Clyde Trust £3400, the customs revenue £427 and the population of the

city 77,385; in 1880 the length of quayage was 4 miles and 382 yards,

the area of the harbour 120 acres, the revenue £223,709, the customs

revenue £956,620, and the population computed at 578,156. "The deepening

and widening of the Clyde have increased the value of the lands on its

sides through Glasgow and seaward a hundred-fold, created the burghs of

Govan, Partick, and the various other burghs that environ Glasgow, given

wealth to thousands, and the means of life to hundreds of thousands;"

and the expenditure up to 30th June 1880 has been £8,786,128, of which

£2,306,766 was paid for interest on borrowed money. The other burghs in

the county contributing to send members to Parliament are Lanark,

Hamilton, Airdrie, and Rutherglen; the burghs of barony are Strathaven,

Biggar, and East Kilbride. The villages and populous places are many.

Estates and Cropping.

From the return of owners of lands and heritages in

Scotland, 1872-73, it appeared there were, outside the municipal

boundaries of Glasgow, 9117 proprietors in the county, of whom 1890

possessed one acre or upwards, and possessed altogether 549,232 acres at

a valued rental of £1,284,592, 18s.; while 7227 owners of less than one

acre had altogether 3865 acres at a gross annual rental of £451,675, 9s.

Inside the municipal boundaries there were 310 owners of one acre or

upwards, who had 3011 acres at a gross annual value of £628,374, 6s.,

and 10,681 owners of less than one acre, who had altogether 2811 acres,

at a gross annual value of £1,713,789, 14s. In all there were within the

municipal boundaries 10,991 owners of 4822 acres, at a gross annual

value of £2,342,164. The municipal boundaries were extended in 1872, and

again in 1878. As might naturally be expected, the rent of land in

different districts varies extremely. In upland parishes land may be

seen at a rent of half a crown to five shillings an acre; in other

places it rents at £6 an acre; while in some localities an acre of land

yields a handsome revenue. Mr Alexander Aikman, Holland Bush, Hamilton,

is entered in the parliamentary return as owner of one acre, which is

rented at £132; and the Airdrie Gas Company is represented as owning one

acre at a value of £700 a year. Within the municipal boundaries of

Glasgow values are much higher. Mr James Arthur, Queen Street, is owner

of an acre which yields the magnificent income of £6923, 10s. a year.

From three acres Sir James Campbell of Stracathro, has £12,912, 5s. of

yearly income. Mr George Martin, 141 St Vincent Street, is on the roll

as owner of one acre, of which the rental is £3928, 10s., other

proprietors of a single acre have from £1000 to £3000 of yearly income.

It will be observed that a large proportion of the

land in the county is owned by proprietors of one acre or upward; and it

may be added that three-fourths of the land are owned by very large

proprietors, while the remainder is parcelled out into moderate or small

holdings. The most extensive landowner is the Earl of Home, Bothwell

Castle, who has 61,943 acres, at a rental of £24,770, besides £4716 for

minerals. The aggregate rent of land in this estate seems to be hardly

8s. an acre. Next in magnitude is the Duke of Hamilton, with 47,731

acres and a rental of £38,441, amounting to fully 16s. 9d. an acre,

besides £56,920, 14s. for minerals. Sir Simon Macdonald Lockhart, Bart.,

of Lee and Carnwath, has 31,556 acres at a rental of £21,050, or fully

13s. 4d. an acre, and £869 for minerals. Sir T. E. Colebrooke, Bart.,

M.P., Abington House, has 29,604 acres at a

rental of £2282 a year, or nearly 7s. an acre. The Earl of Hopetoun,

Leadhills and district, has 19,180 acres, at a rent of £3246, or 3s. 4d.

an acre, and £2246 for minerals. Sir Windham C. J. Carmichael Anstruther,

Bart., Carmichael House, Lanark, has 13,624 acres at a rent of £9228,

and £722 for minerals. Lord Lamington, Lamington House, Biggar, has

10,833 acres, with a rental of £5539, and £788 for minerals. The Duke of

Buccleuch and Queensberry has 9091 acres at a rent of £1544; Colonel D.

C. R. C. Buchanan of Drumpellier, 8549 acres at a rent of £8693, 12s,

and £15,180, 9s. for minerals; R. W. Ewart of Allershaw, Crawford

parish, 8485 acres at £1575; W. E. Hope Vere of Blackwood, Lesmahagow,

6863 acres at £5522, with £5781 for minerals; Mrs Louisa Catterson of

Birkcleuch, Abington, 6870 acres at £1562; William Bertram of Kersewell,

Carnwath, 5863 acres at £2893; the Earl of Eglinton and Winton, 5866

acres at £4097; the trustees of the late Sir W. Stirling Maxwell, Bart.,

Cadder estate, 5691 acres at £8741, with £3231 for minerals; J. W.

Baillie of Culterallers, 4510 acres at £1826; James S. Lockhart of

Castlehill, Carluke, 4422 acres at £5250, and £2183 for minerals. In

addition there are two others who own 4000 acres or upwards,

five others own 3000 acres or upwards, sixteen who own 2000 acres

or upwards, and others of smaller extent. In the county, but especially

in some of the large parishes in the upper ward, there are many small

proprietors, most o£ whom farm their own lands.

According to the agricultural returns issued by the

Board of Trade, the county contains 568,840 acres, of which in 1882

there were 251,121 acres under crops, bare fallow, and grass. Under corn

there were 52,929 acres, of which 3592 were under wheat, 874 barley or

bere, 46,905 oats, 39 rye, 1489 beans, and 30 under peas. Green crop

covered 18,796 acres, of which 7669 were potatoes, 9151 turnips and

swedes, 20 mangold, 51 carrots, 536 cabbage, kohl-rabi, and rape, and

1369 vetches and other green

crops except clover or grass. Of clover, sanfoin, and

grasses under rotation there were 64,713 acres, and of permanent

pasture, or grass not broken up in rotation (exclusive of heath or

mountain land) 113,989 acres. There were 11 acres of flax, and 683 of

bare fallow, or uncropped arable land. Of horses (including ponies) as

returned by occupiers of land, there were 5666 used solely for the

purpose of agriculture &c, and 1944 unbroken horses and mares kept

solely for breeding. There were 64,850 cattle, including 34,483 cows and

heifers in milk or in calf, and of other cattle 10,785 of two years old

and upwards, and 69,582 under two years of age. There were 210,322

sheep, of which 131,046 were one year old and above, and 79,282 under

one year old. There were 7637 pigs.

Geology.

Taking the granite rocks of Galloway as the base,

there are superimposed over them the greywacke and trap which prevail on

the Leadhills and the district adjoining. The pastures of Crawford

parish, chiefly those rocks, thinly covered with soil, are of good

quality, consisting of sweet and nutritious grass. At Roberton there is

a transition to the rocks of the lowland district. About Thankerton are

gravel mounds; and extending in the direction of Biggar is a plain so

little elevated above the level of the Clyde that not much labour would

send that river in the direction of the Tweed. From the western margin

of this plain the Clyde turns north-westward, gently flowing in a wide

valley, across a series of igneous rocks, belonging to the Old Red

Sandstone, which is conspicuous about Tinto. On either side hills rise

with gentle acclivity, those on the south side tending in the direction

of the trap and greywacke, those on the north approaching the great

Lanarkshire coalfield. At Bonnington begin the falls of the Clyde, and,

in a defile through the Old Red Sandstone, the river brawls along for

three or four miles till it tumbles over the last fall at Stonebyres.

From the top of the highest fall to the bottom of the lowest the river

descends 230 feet within a distance of little more than 3½

miles, whereas the fall is only 270 feet in the whole distance of fully

50 miles from Stonebyres to Dumbarton. From Stonebyres downward the

valley broadens, and the course of the river is through the great

coalfield which is the source of industry and wealth to the county. The

coal formation of the middle and lower wards includes bituminous shale,

coal, grey limestone, and clay ironstone, over which there are, in some

places, beds of freestone.

Soil, Climate, &c.

In the report of the Agricultural Commission, 1881,

Mr Hope, one of the Assistant Commissioners, says of the county— " About

one-third under cultivation, remainder unproducing mountain and moorland;

central and western parts generally cold and clayey, with tracts of bog.

South-east part, the soil is light and open, but, from its height,

exposed to frosts. The agriculture is excellent, especially on the banks

of the Clyde." (Report, p. 511). In the upland parishes of

Crawford and Crawfordjohn, as well as the greater part of Lamington and

Culter, the land is high and steep, much of it not susceptible of

agricultural improvement. Three-fourths of Douglas and Les-mahagow

parishes on the one side and of Dunsyre on the other are either moorish,

heathy land, or covered with beds of peat earth, yielding little useful

herbage. Considerable tracts in the parishes of Carluke, Lanark,

Carnwath, Dolphinton, and Biggar are of a similar character. Near the

Clyde it is different even in the upper ward, and there are fertile

districts in all the parishes. In Wiston, Symington, Culter, Biggar,

Covington, Libberton, and Carstairs is a good deal of light, sharp,

turnip and potato soil, which yields excellent crops of these and of

grain coming to maturity about the beginning of September. Some of the

meadows by the river side are exceedingly fertile. In the parishes of

Lanark and Lesmahagow the greater part of the arable land is dry, light,

and friable, but in the latter parish there is clay near the Clyde, some

of which is covered with orchards, and in Lanark there are clay

districts, while the moors are a hard till. Old Red Sandstone is the

prevailing rock. Carluke parish is pervaded, with trifling exceptions,

by a dense blue clay, assuming a reddish appearance in some places,

containing boulders of every size, and from almost every description of

rock, and the soil partakes largely of the same ingredient, acted upon

and altered by the atmosphere, by heat, moisture, and the operations of

the agriculturist. When the rocks crop through this alluvial matter the

soil partakes of the character of the underlying strata, and is

arenaceous over freestone, white or slightly grey earth over fire-clay

or shale, and sometimes a red colour over ironstone. On the Old Led

Sandstone in the southeast of the parish the soil is light, and free in

great measure from clay. Peat soil occurs in different parts of the

parish, but chiefly in the north-west. It overlies the alluvium, except

where limestone and freestone crop out.

In the middle ward the soil varies, but is generally

of a clayey character, a good deal of it with a hard clay bottom

inclined to till; but there are occasional patches of sand or gravel. In

Avondale the soil is light, and is capable of great improvement. The

rocks belong to the coal formation of the second class; and coal, iron,

and especially lime are abundant. Strathaven Moss, extending

to about 200 acres was, half a century ago, utterly worthless;

but it has been drained, and is now yielding splendid crops, some of it

paying £4 of yearly rent per acre. In Stonehouse parish the soil is

generally good. In Dalserf the soil is not well adapted for green crops,

except a tract near the banks of the Clyde, and some patches on the

Avon. Wheat and oats are the principal crops, and turnips were not grown

till within the past few years. Very few sheep are kept, and the chief

industry is dairy farming for the manufacture of butter and cheese. In

Glassford parish there are moss, clay, and light loam. Above 400 acres

of moss are not considered arable; but in a few years this tract may be

under cultivation. In Blantyre parish are mineral deposits, consisting

of coal, freestone, and limestone. At the northern extremity, where the

banks of the Clyde are low, there is an expanse of sandy soil, but

farther east it is strong, deep clay. Toward the south of the parish

there is clay, more light and free than in other parts, but generally

poor in quality. At the south end of the parish is a deep peat moss; and

there are 500 acres of waste and pasture; the remainder is all arable.

Along the west of Both-well, and extending into several adjoining

parishes, is a stratum of new or upper red sandstone. This rock is of a

bright, red colour, sometimes soft and friable, but generally compact

and well adapted for building purposes. Coal abounds everywhere in the

parish, but in the lower division lies at too great a depth to be worked

at present. The coalfield at Law has been estimated to be 53,000 acres

in extent. Iron and limestone abound in the parish. On the north side of

the river, but at some distance from it, resting on clay soil, an

elevated ridge extends along the eastern extremity of Cambusnethan

parish, through the middle of Shotts, where it is high and rocky, and

thence through Monkland parish, declining a little as it advances

westward. Much of the soil in this region is moorish, coarse, and wet.

Dalziell lies in the centre of the great coal district, and abounds in

coal. There is also a flagstone quarry. The soil is chiefly a heavy

clay. There is an expanse of grass land on the holms and haughs near the

Clyde. Old Monkland is superior to other parishes over coal in respect

of fertility; but about 1500 acres are uncultivated, including Gartgill

moss, Lochwood, Drumpellier, and Coatsmuir.

The lower ward is not extensive, but is important in

consequence of being near a large city. A good deal has been improved

and ornamented so as to form summer retreats for prosperous citizens.

With regard to the remainder, the soil consists generally of clay or

sand, naturally very poor. In Cadder parish the greater part of the soil

is of a tilly character.. There are numerous mosses and lochs and a few

good springs, the moss extending to about 300 acres. Great fields of

fire-clay are found near the Glasgow and Garnkirk Railway. The best land

in the parish, part of it on gravel, part on sand, is alongside of the

canal and the Kelvin. In Cambuslang the soil is clay from a few feet to

30 inches thick, beneath which is white freestone twenty feet in

thickness, and then shale to the depth of 30 or 40 feet. Iron and

limestone abound. The whole of Govan parish is arable; and the soil is

of good quality. The Barony parish is diversified in surface, and some

of the low grounds are very fertile. On the whole the district above the

falls is superior to any in the lower part of the county, some parts

excelling in real intrinsic fertility other places 400 or 500 feet less

elevated. The elevation rather than the soil hinders cultivation in the

higher regions, and yet, in some of the highest and wildest districts

there are green spots which indicate the existence of culture at an

early period. Where tillage has not been attempted the pasture has been

much improved by surface draining.

As might be expected from the diversities of

situation and altitude, the climate of the county is varied. The lower

grounds in the west are open to the influences of the Atlantic Ocean,

but the vapours coming from the south-west are intercepted and

condensed by the hills of Renfrew and Dumbarton, and the district about

Glasgow is thereby made rainy but comparatively mild. On the other hand

the force of easterly winds is broken by the higher grounds on the east

side of the county, and the cold fogs which prevail at times on the east

coast are found only to a moderate degree in the west. The greater

amount of cloud, together with the more frequent and heavy rains, is apt

to make the spring late; and when dry weather comes in May and June, as

it often does, with east winds, there is little growth till rain falls

about the end of June. Growth is then rapid, and usually continues well

through the autumn, but the harvest is often late and in danger of being

spoiled by unsettled weather. In the upper ward the moderating influence

of the Atlantic is less perceptible, and the air is purer, but has a

tendency to chilliness; and if the sky becomes clear at night there is

danger of hoar frost except in sultry summer weather. On the highest

hills the climate is severe. Fogs gather round the hills chilling the

atmosphere, summer heat is often interrupted by cold and stormy gusts;

and in winter the hills are often covered with snow for weeks together

when the lower lands have a moderate temperature.

Surface, and Modes of Farming.

In the south corner of the county, bounded on the

south and south-west by Dumfries-shire, is the parish of Crawford, 18

miles long by 14½ wide, and including one of

the wildest districts of the southern highlands. In extent it is larger

than the whole lower ward. The mining village of Leadhills is computed

to be 1300 feet above the level of the sea, and is the highest inhabited

village in Scotland; but the Lowthers, a ridge of hills more to the

eastward, are 1100 feet higher, making a total height of 2409 feet above

the sea level. Among the hills in the east of the parish rise several

important rivers, as indicated in the lines:—

"Avon, Annan, Tweed, and Clyde

A' rise out o' ae hill side."

On its way through the parish, the infant Clyde

receives the Daer, the Elvan, the Powtrail, the Midloch, Camp, Glengonar,

and other tributaries. The village of Crawford, 3 miles south of

Abington, is composed of cottages, built in a straggling manner near the

banks of the Clyde; and the ruins are still visible of the castle once

the stronghold of the Earls of Crawford.

In this extensive parish there are forty proprietors,

and the rental, as indicated by the valuation roll, is £24,229, 2s. The

Duke of Buccleuch owns two farms, consisting wholly of hill land—Kirkhope,

occupied by Mr James Milligan at a rent of £720, and Whitecamp, occupied

by Mr Richard Vassie at £480. Sir T. E. Colebrooke, Bart., MP., has

eight large farms, besides others of smaller size. Normangill is let to

Mr Richard Vassie for £1100; and Crookedstone to Mr John Borland for

£1225. The large extent of meadow and grazing land on this farm, which

is enriched by deposits from the overflowing of the Daer and Powtrail,

enhances considerably the value of the farm. It carries a stock of

blackfaced sheep, which has recently been changed from a Cheviot flock

on account of the severe winters and cold summers lately experienced. It

also carries a large lot of cross and Highland cattle on the holm land.

Castlemains is occupied by the representatives of the late Mr David

Tweedie at a rental of £525; and it carries a good Cheviot stock,

besides a small remnant of a once famous herd of Ayrshire cattle. Other

farms on this estate are let at from £300 to £600 a year. The Earl of

Hopetoun is proprietor of Leadhills, and has a rental of £4045 for lead

mines. He likewise owns several large farms. Glenochar and Glengeith are

let to Messrs Gideon Pott and Mr H. Tait, non-resident tenants, for

£1363. They carry a good stock of Cheviot sheep. The farm of Smith-wood

is let to Mr William Wilson for £725. The farm of Mumerie, on the south

bank of the lower Daer, is one of the most extensive in the parish, is

stocked with blackfaced sheep, and tenanted by Mr Thomas Wilson at a

rental of £1375. The representatives of the late Mr Tweedie hold three

farms at a rental of £1086, 16s. The parish is almost wholly pastoral,

with the exception of cultivated belts along the banks of the Clvde. The

hills adjoining the river are generally grassy, and used to carry

Cheviot sheep; but, owing to the severe winters of the last ten years,

these have largely given place to the hardy blackfaced stock. During the

last ten years fourteen hirsels, containing 8000 sheep, have been

changed from Cheviot to blackfaced in this parish alone.

The area of the parish is 65,400 acres. In 1881 there

were 384 inhabited houses, and a population of 1763; in 1871 the

inhabited houses were 374 and the population 1829. In 1791 the parish

was farmed by 15 store farmers; in 1859 there were 28, of whom 13 who

farmed 40 per cent. of the parish were nonresident. In 1859 it was

estimated that the parish contained 19,500 Cheviot, and 12,000

blackfaced sheep, and 500 feeding sheep. There were 56 shepherds, 18

servant men, 6 lads, 46 women, 8 girls, 2 young horses, 46 farm horses,

11 saddle and harness horses, 302 milk cows, 116 queys, 58 calves, 116

feeding cattle, and 58 swine. These figures are exclusive of the people,

cows, crofts, and kailyards in the village of Leadhills.

The adjoining parish of Crawfordjohn contains 26,357

acres, with a valued rent of £11,099, 3s. a year; and there are 47

proprietors on the valuation roll. In 1881 there were 166 inhabited

houses, with a population of 843, a decrease of ten during the last ten

years. In 1861 the population numbered 980. The parish is about 12 miles

in length, and is drained by the Dun-eaton water which rises in

Cairntable and joins the Clyde one mile below the village of Abington. A

great part of the parish is owned by Sir T. E. Colebrooke, Bart., M.P.,

whose summer residence is at Abington House, adjoining the pretty little

village of Abington, the prosperity and picturesque appearance of which

dates from the accession of the present holder of the Colebrooke estates

in 1838. Sir Edward Colebrooke, who is ably supported by his factor,

John Ord Mackenzie, Esq., of Dolphinton, has greatly increased the

amenity of his estate by many plantations, judiciously placed so as to

combine shelter with picturesque effect. They are intelligently alive to

everything that will improve the estate. The farm steadings are

commodious, and adjoining each of them is a hay shed capable of

containing all the hay produced on the farm, which the tenant finds to

be a great advantage. In the summer of 1883 Sir Edward erected a silo

capable of holding 41 tons of ensilage, on the farm of Nether

Abington, with a view to experiment with the meadow hay as to the

suitability for making ensilage. Large tracts of land have been drained

on the estate within the last thirty years, the proprietor being always

willing to supply the money at 5 and 6 per cent. wherever draining is

necessary. The rental of arable land in the district is about £1 per

acre, green hill 10s., and heath and mountain land from 5s. downwards.

Sheep stocks are rented at 9s. to 10s. for Cheviot sheep, and 1s. less

for blackfaced. There is an agricultural show held at Abington in the

last week of August, open to the adjoining parishes, where there are

annually seen some excellent specimens of the several breeds of stock

for which the district is famous. The farms in this parish are part

dairy, part sheep. Ayrshire cattle alone are reared, and dairies have

from 15 to 40 cows. Young cows are reared to a considerable extent on

every farm, and are kept till they are three years old, when they have

their first calf. The milk is manufactured principally into cheese in

summer, and sent to Glasgow during winter. The cheese consists of

Cheddar and Dunlop. The sheep stock consists of both Cheviot and

blackfaced; but, with a few changes from Cheviot into blackfaced in

recent years, the hardy breed now predominates. The most notable farm on

the estate is Nether Abington, tenanted by Mr John Morton at a rent of

£550 a year, on which great improvements have been made, to be

afterwards noticed. Among others are Crawfordjohn farm let to Mr Edward

Watson for £380, Over Abington to Mr James Paterson at £346, 6s.,

Gilkerscleuch Mains to Mr Thomas Inch at £354, 13., Liscleuch to Mr John

Williamson at £373, 12s., and Boghouse to Mr Alexander Dalgleish at

£358. The Earl of Home has several large farms, including Netherton and

Blackhill let to Messrs David and John French at £980, and Stonehill to

Mr Ebenezer Ritchie at £645, 13s.

In the west of the upper ward, 12 miles long by 4 to

7 miles wide, and extending from the county of Ayr to the river Clyde,

is the parish of Douglas, including the fertile and beautiful vale of

Douglas water, but consisting chiefly of high hills covered with grass

to their summits, and stretching away into moorland wastes so extensive

that there are said to be over 25,000 acres of moor in the parish. The

fertile vale of Douglas water, however, maintains the character bestowed

long ago, as "a pleasant strath, plentiful in grass and corn." This

stream, one of the largest tributaries of the Clyde, rises in Douglas

Rig, Cairntable, and after a course of 16 miles, three-fourths of it

through Douglas parish, joins the Clyde, having received some smaller

streams, such as the Monkburn, the Carmacoup burn, the Kinnox, the

Poniel, and others. These all contribute to the beauty, and promote the

verdure of the district. Coal, limestone, and freestone are worked in

the parish, which likewise abounds with marble, Besides the town of

Douglas, which has seven annual fairs, there are the three small

villages of Rigside (inhabited chiefly by colliers) Tablestone, and

Redhill. On the valuation roll are 107 proprietors, many of whom are

owners only of houses and pendicles in the villages; nine-tenths of the

parish are owned by the Earl of Home, as representative of the Barons of

Douglas. The area of the parish is 34,137

acres, and the valued rent £22,496, 17s. In

1881 there were 441 inhabited houses, and 2641 in habitants; in 1871 the

inhabited houses were 420, and 2624 of a population. The hills are

numerous and high, including in the west and north, Little Cairntable,

1693 feet; Douglas Rig, 1454; Parish Holm, 1400; Hareshaw, 1527;

Monkshead, 1594; Hag-shaw, 1540; Commonhill, 1445; and Windrow, 1297; in

the south and east, Northbottom, 1435; Dryriggs, 1443; Auchendaff, 1399;

Kinnox, 1270; Hartwood, 1311; Auchendaff, 1286; and Wild-shaw, 1136. In

the extreme east, but just beyond the boundary, is Cairntable, 1942 feet

high. There is no natural wood of any extent in the parish, but patches

of birch may be found in hollows among the hills. There are, however,

many thousands of acres of plantations, growing larch, spruce, fir, oak,

ash, and elm. There are many extensive farms producing

the finest specimens of blackfaced sheep. On the banks of the

Douglas Water, near the village, is Douglas Castle, an elegant mansion,

surrounded by extensive plantations; and in a park stretching away to

Cairntable, some ash trees are pointed out on which the powerful Earls

of Douglas were wont to hang persons who came under their displeasure.

The spire and aisle of St Bride's Church are still preserved, and in a

vault are the tombs of the family, including "the good Lord James," the

friend of Bruce, and the hero of Castle Dangerous. The remains of

that fortress still exist, near the modern mansion. The policies, grass

parks, and farm of Douglas Castle are placed on the valuation roll at

£1269 a-year; the stables, gamekeeper's house, lodge, and garden at

£250; and the land under wood at £1100. The minerals at Rigside and

Glasphin are let for £1170. In the parish there are at present fully

7000 blackfaced sheep, exclusive of lambs, but they are gradually

increasing; and 5000 Cheviots, exclusive of lambs, but gradually

diminishing. The annual loss by death, exclusive of lambs, is about 2

per cent. of blackfaced, and 4 per cent. of Cheviots. The usual rent per

sheep is 6s. to 12s. on blackfaced and Cheviots. There are no cross bred

lambs except in parks or on some other low-lying land.

Lesmahagow, 14 miles long by 12 miles in width,

extends from the banks of the Clyde, in a series of broad swelling

uplands, to the borders of Ayrshire, where the hills reach an elevation

of 1200 feet. It has an area of 41,299 acres, and the valuation roll

shows a rent of £67,694 a year. In 1881 there were 1877 inhabited

houses, and a population of 9949; in 1871 the inhabited houses were

1364, and the population 8709. There are 501 proprietors on the

valuation roll, many of whom have small holdings. Among the principal

proprietors are John Stirling Alston, Esq.; W. C. S. Cuninghame, Esq.,

of Caprington Castle, Kilmarnock; the Earl of Home; the Duke of

Hamilton; James Charles Hope Vere, Esq., of Blackwood; and the trustees

of the late General Sir Thomas Monteath Douglas of Stonebyres. The

parish is drained by the Poniel, the Douglas, the Logan, the Nethan, the

Kype, and other streams; and along their banks, as well as near the

Clyde, are fine alluvial lands. The village of Lesmahagow is beautifully

situated on the Nethan, 6 miles from Lanark; and, besides being the

capital of a parish extensive, fertile, and populous, its prosperity is

enhanced by a large cotton mill in the neighbourhood. The other villages

are Kirkfieldbank, Kirkmuirhill, Boghead, Hazelbank, and New Trows. Near

Crossford, on the banks of the Nethan, are the ruins of Craignethan

Castle, described by Sir Walter Scott under the name of Tillietudlem:

and along the banks of the Clyde, from Kirkfieldbank to Crossford are

many orchards. The parish is one of considerable agricultural value. The

orchards near the Clyde contain apples, pears, plums; and gardens yield

gooseberries, currants, rasps, and strawberries. In the higher districts

the crops are late and harvest precarious. The common rotation is the

five or six shift, but freedom of cropping is generally allowed. The

average yield of oats per acre is 4 to 6 quarters, with an average

weight of 35 to 38 lbs. a bushel. The common yield of potatoes is 7 to 8

tons an acre, of turnips 12 to 15 tons, and of hay 2 tons. Grain is sown

in the last week of March and the first week of April, turnips from the

15th of May till the beginning of June. Harvest begins about the middle

of September. The stock consists of Ayrshire cows and blackfaced sheep,

and stock of both kinds has improved during the past twenty-five years.

There is now less cropping and more cattle kept; and they are much

better fed and sold younger. A good deal of land has been drained, the

proprietor giving the tiles; and steadings and fences are generally

good. Servants are generally lodged in the farm houses, and the wages

are at least a third more than they were thirty years since. Bents from

1850 till 1870 rose 30 to 50 per cent., but where leases have been

renewed lately there has been little or no change. The chief dairy

produce of the district is Dunlop cheese.

In early times Lesmahagow was a place of considerable

consequence. In the year 1144 David I. granted the church of that place

as a cell to the abbey of Kelso, and, by the same charter, conferred on

it the secular privilege of sanctuary, within a space marked by four

crosses, in these terms,—"whoso, for escaping peril of life or limb,

flees to said cell, or conies within the four crosses that stand around

it; of reverence to God and St Machutus, I grant him my firm peace." The

"king's peace" was a privilege attached to the sovereign's court and

castle, but which he could confer on other persons or places; and the

penalty for raising the hand to strike within the king's girth was four

cows to the king, and one to him whom the offender would have struck.

For slaying a man "in the king's peace" the forfeit was nine score cows

to the king, besides "the assythment" or composition to the kin of him

slain "after the assise of the land." The pastoral character pertains

largely to the parishes of Roberton and Wiston, Lamington, and Culter.

The united parish of Roberton and Wiston, on the west bank of the Clyde,

is 5½ miles long by 2½

in width, with an area of 13,140 acres, of which 4606 acres are arable,

and 7976 heathy pasture. The valuation is £8636, 7s. There were 116

inhabited houses in 1881, and 562 inhabitants; in 1871 the houses were

135, and the inhabitants 680. In 1861 the population was 786. The parish

has a hilly surface, rising from the Clyde toward the north, where Tinto

forms the boundary. The farming is dairy and pastoral, most of the sheep

being blackfaced, varied with a few flocks of Cheviots. The Earl of Home

is the chief proprietor. Mr Johnston Ferguson, Wiston Lodge, owns

several farms, and has a residence at the base of Tinto. Mr M'Queen

Mackintosh also has several farms, and has his comfortable looking house

on the banks of the Clyde, close to Lamington Station.

The united parish of Wandell and Lamington, on the

southeast bank of the Clyde, is 9 miles long by 4 in width, with an area

of 12,820 acres; and a valued rent of £8293, 14s. It contained 62

inhabited houses in 1881, with 316 of a population; in 1871 there were

63 inhabited houses, with 332 inhabitants; in 1861 the population was

380. The parish has an upland surface, rising to a height of 1300 to

1400 feet; but there are arable haughs near the Clyde, 400 acres in

extent, besides patches of holm land scattered here and there. Many

streams well stocked with trout flow down from the hills, and are

attractive to anglers. At Lamington village is a station of the

Caledonian Railway. The holm or level land is well cultivated,

diversified with hillocks and gracefully adorned with trees; the hills

are smooth and dry, and afford excellent pasture. In the holms the soil

is generally a deep rich loam, and toward the hills a free and kindly

soil. An embankment along the Clyde, the whole length of Lamington

parish, was constructed in 1835-36 at a cost of £2000, and gives great

protection to the holm lands. Dairying and sheep breeding form the usual

routine of agriculture in the parish. The sheep are blackfaced. On

account of the expense and the difficulty in securing efficient

management of the dairy in recent years several herds have either been

greatly reduced, or have given place wholly to the more easily managed

woolly tribe. Lord Lamington owns fully half the parish, and has a

stately house near the village of Lamington, the surroundings of which

have been greatly beautified by the present holder of the Lamington

estate.

Culter, in the south-east part of the upper ward, is

7½ miles long by 3½

wide, with an area of 10,175 acres, and a valuation of £7000, 3s. There

were 92 inhabited houses in 1881, with 428 inhabitants; in 1871 the

houses were 98 and the inhabitants 447. In 1861 the population was 484.

There are on the valuation roll eleven proprietors, the principal of

whom is John Menzies Baillie, Esq., of Culterallers. Part of the parish

is well wooded, but toward the south, where it forms the watershed with

the county of Peebles, the hills are high and bare. The farm of

Culterallers, on which is a notable stock of blackfaced sheep, is let,

along with Snaip, to Mr Robert Watson for £724. The house and home farm

of Culter Maynes are on the east side of the Clyde, and the grass parks

are let for £660 a year. Mr D. Sim, the proprietor, constructed high

embankments, thus adding to the value of the rich holms by protecting

them from the river floods. There are about 2100 acres of heathy

pasture, most of it rough; and in 1859 it was calculated that the parish

contained 6000 Cheviot and 5500 blackfaced sheep, 538 cows, 212 queys,

162 calves, and 132 horses. On the estate of Culterallers, near the

mansion, is a maple tree, which, in 1800, measured 8 feet in

circumference at 3 feet above the ground; in 1835 it measured 10 feet,

and was believed to be the largest tree of its kind in Scotland,

excepting one at Roseneath in Dumbartonshire. A limb has been broken off

since then, which weighed from 20 to 30 cwts. The present measurement is

about 9 feet, and the only limb left is a little over 6 feet at 3 feet

above the trunk. It was considerably more, but by the fall of the limb

the trunk was divided almost right down the centre. Great efforts have

been made to save the remainder by covering it with zinc, then removing

the covering and cleaning and painting the broken part; but now, though

apparently healthy in foliage, it is open from the break to the ground.

A young tree grown from seed of the large one was planted in 1882.

Pettinain is a small parish with an area of 3900

acres and a valuation of £4800, 10s. In 1881

the inhabited houses were 59 and the population 360; in 1871 there were

67 houses and a population of 366; in 1861 there were 407 inhabitants.

The parish is 3 miles long from north-east to south-west, with an

extreme width of 2½ miles. The surface is

uneven, and Westraw Hill attains a height of 1000 feet. The soil is of

various qualities in the low grounds; in the uplands it is moorish. The

village of Pettinain is situated on the banks of the Clyde, 4 miles east

of Lanark, and is within easy reach of Carstairs, Carnwath, and

Thankerton stations. Westraw House, in this parish was the residence of

the last Earl of Hyndford, who took much interest in the agriculture of

the district; and in the parish there are still some good and well

managed farms.

Carmichael parish is 5½

miles long by 3 to 4½ in width, and has an

area of 11,314 acres, with a valuation of £9967, 1s. In 1881 there were

141 inhabited houses, and a population of 770; in 1871 there were 132

inhabited houses and 708 of a population. In 1861 the population was

886. There are 8 proprietors on the valuation roll, but some are small,

and nearly the whole parish belongs to Sir W. C. J. Carmichael

Anstruther, Bart., and the Earl of Home. The parish has a very

diversified surface, extending from the Clyde, where it is joined by the

Douglas water, to the top of Tinto, 2316 feet high. Except Tinto, the

elevations are not great; and there is a gradual transition from the

wild grandeur of the pastoral region to the greater mildness and

fertility of the middle ward. The soil in general is light and friable,

and near the Clyde is fertile. The farms are of moderate size, few of

them exceeding £200 a year of rent, and the amount per acre is from £1

to £1, 10s.

The neighbouring parish of Symington, likewise on the

left bank of the Clyde, has an area of 3504 acres and a rental of £6496.

In 1881 there were 108 inhabited houses and 462 inhabitants; in 1871 the

inhabited houses were 184, and the inhabitants 442. In 1861 the

population was 528. The parish contains some arable and fertile land

near the Clyde, which now gently glides with many windings through a

tract of alluvial meadows; and westward it extends to the top of Tinto.

There are twenty-five proprietors on the valuation roll, with some good

sized farms; but there are many remnants of old pendicles rented at £16

to £45; and the aspect of the parish, with thatched homesteads and byres

in a line with the houses, indicates the existence of some farmers who

do the whole farm work by themselves and their families.

On the opposite bank of the river is Libberton

parish, with an area of 8231 acres, and a valued rent of £8105, 12s. In

1881 there were 114 inhabited houses, with a population of 625; in 1871

the houses were 123, and the population 691. In 1861 the population was

836. The parish includes some fine haugh land along the banks of the

Clyde and its tributaries, the north and south Medwyns, but towards the

east it is more elevated. There are 20 proprietors on the valuation

roll, the principal of whom are Sir S, M. Lockhart, Bart., John George

Chancellor, Esq., of Shieldhill, and the Society for the Propagation of

Christian Knowledge. The estate of Shieldhill has a gross rental of

about £2000, and the average rent of the estate is about £1, 10s. per

acre. The gross rent has increased about £400 in the last twenty-five

years. In the same period about 300 acres on this estate have been

reclaimed at a cost of about £15 an acre, and 450 acres have been

planted. Twenty years ago Mr Brown, of Libberton Mains farm, on the

Carnwath estate of Sir S. M. Lockhart, Bart., incurred the expense of

building large tanks and erecting a steam-engine for the purpose of

utilizing the liquid rejected by the dung heap. His idea was that about

six acres of land in grass near the steading were sufficient to absorb

beneficially all the liquid manure on his farm of about 700 acres, on

which the whole straw and turnip crop were consumed. This arrangement

lasted for some years, but has long been discontinued.

Covington parish has an area of 5114 acres, and a

valued rental of £6725, 11s. In 1881 there were 104 inhabited houses,

and 444 of a population; in 1871 the houses were 104, and the population

454. In 1861 the population was 532. The chief cause of the decrease of

population in this and neighbouring parishes is the failure of hand-loom

weaving, at one time the only industry competing with farm labour, but

now almost unknown owing to the introduction of power looms. In the

parish there are 17 proprietors on the valuation roll, but most of them

are only feuars of a house and garden. There are only four proprietors

of any extent; of whom the principal are Sir W. C. J. Carmichael

Anstruther, Bart., and Sir S. M. Lockhart, Bart. There is a considerable

extent of flat land of good agricultural value, and the upland slopes,

which attain no great elevation except on the sides of Tinto, are

clothed with grain and green crops alternating with sound pasture. Near

the kirk, and surrounded by noble old trees, are the ruins of Covington

Tower, an ancient fortress of the Lindsays; and near it an ancient

dovecote also of great age, to which the only access for pigeons is from

the top. It is inhabited by hundreds of pigeons. The farm of Covington

Mains, conjoined with Covington Mill, both on the estate of Sir S. M.

Lockhart, Bart., is farmed by Mr Allan M'Lean, and carries a good dairy

stock. The neighbouring farm of Meadow-flatt is held by Mr Hugh Lindsay.

The buildings are excellent, and the steading is finely situated on the

south slope of a hill looking out on Tinto and the mountainous district

of the upper ward. There is a breeding and feeding stock of sheep and

cattle on the farm, which is in all respects well managed. As an

indication of the good feeling which exists between landlord and tenant

on the estate of the Lockharts of Lee, it may be stated that the farm of

Meadow-flatt has been held by the Lindsay family for five generations,

or over 160 years, and that the present occupant, Mr Hugh Lindsay, till

four years since, held the adjoining farm of Covington Mains, which had

also been for five generations in possession of his ancestors in the

female line, named Prentice. Among other prominent farms in the parish

are Covington, Hillhead, let to Mr Archibald Stodart, and Lower and

Upper Warrenhill, let to Mr John Tweedie for £285, and Sheriff-flatts to

Mr William Bell at £450.

Biggar parish is on the east border of the ward,

adjoining the county of Peebles. It has an area of 7272 acres, and a

valued rental of £14,774. In 1881 there were 466 inhabited

houses, and a population of 2128 ; in 1871 the houses were 354, and the

population 2013. In 1861 the population was 1999. There are 185

proprietors on the valuation roll, of whom the greater proportion are

small. In the Old Statistical Account, 1791, it is reported that "the

land in the neighbourhood of Biggar is mostly distributed in small farms

of £10 and £15 each; in the country parts of the parish some farms are

let at £50, and others at £70, and one at £150." With the beginning of

this century improvements were rapid. New steadings were built, drains

were cut, dykes were constructed, and hedge-rows were planted. Two

thousand acres of land very soon assumed a new aspect, and became

greatly increased in value. From Boghall to Broughton Bridge, a distance

of 4 miles, the Biggar water was deepened 2 feet, by which it was

estimated that 500 acres of land were increased £1 an acre in value.

Even the climate has been improved by the drainage of extensive

morasses, executed by various proprietors. The soil in the parish

includes clay, sand, gravel, loam, and peat moss. It carries good crops

of oats, barley, peas, turnips, and potatoes, but is not well adapted

for beans and wheat. The dairy has long received much attention ; and

most of the farmers have a stock of milk cows, the butter and cheese

produced from which are much esteemed. The valley is 628 feet, and the

town 695 feet, and the hills 1190 to 1260 feet above the sea level; one

result of which is that the atmosphere is keen, and the winters severe;

but the air is neither so damp nor so cold as might be expected, as the

climate is equally beyond the range of easterly harrs from the German

Ocean and excessive rains from the west. So level is the valley that the

Biggar water, from its source to its junction with the Tweed at

Drummelzier, has a fall of only 25 feet. There are no natural woods, but

remains of alder, oak, and birch are dug up from the mosses, and hazel

nuts have been discovered several feet below the surface. In modern

plantations the ash and elm are the favourite hardwood trees, after

which are the beech and the plane. The general rent of land in the

district is about 25s. an acre; and the rotation extends to six or seven

years. The style of farming includes a portion of grain, turnips, and

potatoes; a dairy; some feeding cattle, a few feeding sheep, some young

calves reared, and lambs bought, fattened, and sold in the best market.

There has been considerable improvement in the stock, and the tendency

at present is towards more feeding with less dairy farming.

The north-eastern extremity of the county is occupied by the parishes of

Walston, Dolphinton, and Dunsyre. Walston has an area of 4366 acres, of

which nearly 3000 are arable. In 1881 there were 74 inhabited houses,

and 340 of a population; in 1871

the houses were 78 and the

inhabitants 425. The most extensive proprietor is Sir S. M. Lockhart,

Bart. The valuation is £3349, 18s.

Dolphinton, in the north-east angle of the county,

has an area of 3574 acres, and a valued rental of £3517, 11s. In 1881

the inhabited houses were 49 and the population 292; in 1871 there were

50 inhabited houses and 231 of a population. In 1861 the population was

260. There are eleven proprietors on the roll, but the great proportion

of the property is owned by John Ord Mackenzie, Esq., W.S., a gentleman

who is factor for several important estates in upper Clydesdale, and to

whose judicious management the upper ward is much indebted. The parish

is picturesquely situated east and north of the Black Mount of Walston

and the hill of Dunsyre, and between the sources of the South Medwyn and

the Tarth waters. The soil is, in some parts, a dry, friable earth or

sandy loam of various depths, but in other places there is clay of a

rusty iron colour. In 1791 the parish was divided into small farms, each

keeping several cottages, in the usual style of that time, but now the

farms have been much enlarged, and are cultivated in the most approved

style of modern agriculture, in which there is cordial co-operation

between proprietor and tenant. Dolphinton House is a handsome mansion

situated in a well wooded park. Near Garvald House the South Medwyn

water separates into two streams, one flowing toward the Tweed, the

other going to join the Clyde. The fork in the stream where the division

takes place is called the Salmon Leap; and it is alleged that salmon and

salmon fry killed above the falls of the Clyde may have got into that

stream from the Tweed by way of the Lyne, the Tarth, and the Medwyn, or

by Wolfclyde Bridge, near Biggar, where the waters of the Clyde, when in

flood, pass into a feeder of the Biggar water and thence into the Tweed.

The parish of Dunsyre has an area of 10,743 acres, of

which about 2000 are arable, and 8000 are heath or rough pasture; the

valuation is £6425, 19s. In 1881 there were 44 inhabited houses, and 254

of a population; in 1871 the houses were

50, and the population 302; in 1861 the

population was 312. Nearly the whole parish belongs to Sir S. M.

Lockhart. The hill of Dunsyre, 1313 feet high, is the southern terminus

of the P'entlands, and is composed of stone similar to that of Arthur's

Seat or Salisbury Crags. The South Medwyn water rises from the

Craigenvar hills in the parish of Linton, but soon turns westward into

Dunsyre parish, where it is joined by the West-water, a stream of nearly

equal volume coming south from the Black and Bleaklaw hills. So flat is

the vale between Dunsyre and Walston that the Medwyn water falls only 15

feet in three miles. It is a sluggish stream, but good for anglers, the

trout being generally red, of considerable size, and

superior in quality to those of the Tweed and Clyde. Pike of large size

are found in the deep pools. Great improvement has resulted from the

straightening of the Medwyn, and the draining of land traversed by it.

In the parish there are beds of pure limestone resembling grey marble;

also ironstone and coal, but they are not wrought. The soil is generally

light and sandy in the eastern district, but, toward the west, the

subsoil consists of clay, sand, gravel, and stones covered with a light

soil that speedily becomes covered with heath unless kept under

cultivation. The system of agriculture consists of stock and dairy

farming, to which cultivation is made subordinate. The rotation of crops

on arable land is the five or six shift. Much attention is paid to the

dairy, and the milk houses are models of cleanliness. Stock has improved

a good deal within the past twenty-five years; and a good deal of land

has been broken up. On the farm of Weston, Dunsyre, within the last

twelve years about 100 acres have been broken up and drained, and nearly

all the arable part of the farm has been limed. Mr Brown keeps feeding

stock, rearing about 15 calves, and purchasing others which are fed off

in two years. The land is generally well watered, the houses are

convenient and in good repair, but the fences are chiefly wire, which is

not considered suitable for horses and cattle. The rent of arable lands

average from 26s. to 30s. per imperial acre. Owing to the lightness of

the soil it is considered that a pair of horses can cultivate 100 acres.

Rents have increased since 1850 in some cases 40 per cent. The hill land

is chiefly heather, but in some cases green mixed with heather; and the

hill sheep are all blackfaced.

Carnwath, about the middle of the east side of the

county, extends from the banks of the Clyde in a northerly direction to

the borders of Mid-Lothian, and is 12 miles long by 8 in width. Its area

is 30,446 acres, and its valuation £42,593, 14s. The number of inhabited

houses in 1881 was 1113, with a population of 5831; in 1871 there were

1073 houses with 5709 of a population. In 1861 the population was 3594.

On the valuation roll appear the names of 240 proprietors, but the

greater part of the parish belongs to Sir S. M. Lockhart, Bart., who has

sixty-five tenants on the roll, some of them with large and good

holdings. The writer of the report in 1791 describes the land near the

village as sandy, with a mixture more or less of black loam; the holms

near the Clyde a deep, rich, clay; those on the Medwyn more inclined to

sand; in the Muirland either a cold stiff clay, or moss with clay or

sand at bottom. In the dale land, as locally named, "the grass is sweet

and good, fit either for rearing or feeding black cattle or sheep" but

"in the Muir-lands much of the pasture is boggy, producing plenty of a

coarse, sour, benty grass calculated better for rearing than fattening

the cattle upon it; and large tracts of such land lie in the course of

the burns which permeate the northern part of the parish." It is added

that "flow mosses abound in the parish 20 to 30 feet deep, much on a

dead level, and irredeemable." In 1834 it was said that "draining has

been executed to a great extent in every part of the parish within the

last forty years;" and "within the last thirty years there has been

taken out of moss and brought into crop from 800 to 1000 acres."

Attention was also given to the stable, the byre, and the barn, but the

farm houses were not considered relatively so good as the steadings.

Since 1834 the parish has been still further improved, and that to a

large extent. According to the Ordnance Survey there are now 16,526

acres of arable land, of moss and rough pasture 4387, meadow 85, heathy

pasture 3117, rough pasture 4066, and wood 1296. One of the largest and

most important farms in the parish is Calla, the property of Sir S. M.

Lockhart, and tenanted by Mr A. Fleming. The farm includes 350 acres of

arable land, with 900 acres of pasture and moor. The farmhouse is

substantial and commodious, and the lawn and adjuncts are kept with

admirable neatness. The steading is stone-built and slated, uncommonly

well arranged and thoroughly substantial. Through the kitchen there is

access to the dairy, and the passage is continued to the byre and over

the whole steading, without the necessity of going outside. The ordinary

produce of the dairy is Dunlop cheese, the making of which is

facilitated by all modern improvements. The byre is 120 feet long, by 21½

feet wide, and 9 feet high, and it is arranged to keep forty cows. The

straw barn and hay shed have easy communication with the byre. Though

surrounded by higher grounds there is no adequate water supply by

gravitation, but water is forced up by a ram from a lower level. The

farm has been occupied by Mr Fleming for a lease of nineteen years, and

about half of a second lease has expired, during which period great

improvements have been made. Much land, formerly moor, has been broken

up, fenced, drained, and limed, and brought under the plough. Part of

the fencing has been done by the proprietor. Some of the fences are

wire, others are stone dykes. The soil is generally light. The rotation

of crops on the arable land extends over eight years usually; but less

is ploughed than there was formerly, and hay is cultivated instead. The

sheep on the hill land are blackfaced ewes, and all the stock of both

sheep and cattle is bred on the farm. They are fed chiefly on the

produce of the farm, but partly and increasingly on cake and meal. The

surplus animals are sold partly at public sales, partly at home.

Another extensive and valuable farm is Lampits, also

in the estate of Sir S. M. Lockhart, and occupied by Mr Mather. Situated

within a mile east from Carstairs Junction, the farm has a good

proportion of holm land, which is liable to be overflowed by the Clyde,

but the steadings on East and West Lampits are finely placed on elevated

sites, and the farm buildings are all in the best style. The farm is

arable with a dairy, but the cows are let to a lower or dairyman.

Mr Purdie Somerville occupies the farm of Muirhouse

on the same estate, but in the parish of Libberton. The stock consists

of cattle, pigs, and sheep; the two former reared on the farm, the sheep

purchased, fed, and again sold. Through better feeding the stock in the

district has improved in recent years. There has been little change in

the system of cropping, but a good deal of moor has been brought under

cultivation; and, on the whole, there is more stock, and better kept.

Mr Anderson, West Forth, has a farm of 300 acres, for

which he pays £394 of rent. About 50 acres of oats are grown each year,

with a proportion of turnips and potatoes; but the principal stock

consists of 52 Ayrshire cows, and the industry of the farm is the

production of butter. The whole produce is consigned to one merchant in

Edinburgh, who pays 1s. 6d. a pound all the year. In winter the cows are

fed on pease meal, hay, and boiled chaff; and Mr Anderson calculates

that the amount paid for feeding is equal to the rent. On the farm there

are 50 acres of natural meadow, and 50 acres improved out of moss, and

sown with Timothy. The meadows are top dressed with 18 to 20 cart loads

of dung to an acre.

The village of Carnwath is a station on the

Caledonian Railway, 7 miles from Lanark and 25 from Edinburgh, and was

doubtless coeval with the first settlement of the Somervilles in the

12th century. In 1451 it was erected a burgh of barony. It was formerly

a quaint, old-fashioned place, consisting of thatched cottages, badly

arranged; but is now a clean little town, half-a-mile long, containing a

double line of stone-built and slated houses, with some specimens of the

older type still left. A mile to the north-west are the ruins of

Cowdailly or Cowthally Castle, the fortress of the Somervilles, on a

promontary projecting into the morass—a dismal tract called Carnwath

Moor—which extends from Causeway-end in Lothian to Carnwath, and through

which the traveller from Edinburgh approaches this part of Clydesdale.

There used to be annual fairs in Carnwath for horses, cattle, and sheep,

but they have fallen into disuse, with the exception of two in the year

for hiring servants. The other villages in the parish are Forth,

Newbigging, and Braehead. In the parish there are quarries of lime and

freestone, and extensive ironworks founded in 1779 by two brothers named

Wilson, who built the village of Wilsontown for the accommodation of

their workpeople. The situation was exceedingly convenient, as coal,

ironstone, limestone, and fire clay were all on the ground where the

blast furnaces were built. The works were purchased in 1821 by Mr Dixon

of the Calder Iron Works.

Carstairs, extending from the north bank of the Clyde

to the borders of Mid-Lothian, between Carnwath on the east and Lanark

on the west, consists of a higher and a lower district, separated by an

elevated ridge. The Mouse water traverses the centre of the parish. The

area of the parish is 9820 acres, of which 6010 are arable, and 1857

rough pasture; and its valued rent is £15,974, 13s. In 1881 the

inhabited houses were 387, and the population 1955 ; in 1871 the houses

were 258, with a population of 1718 ; and in 1861 the population was

1345. On the valuation roll there are fifty-three proprietors, of whom

the principal is Robert Menteith, Esq., of Carstairs. The mansion is an

elegant Gothic structure, situated close to Carstairs Junction, and

surrounded with fine trees. The lawn, gardens, and shrubberies are

extensive and well arranged, but an expanse of rough heather in close

contiguity shows the wild and moorish character of the soil in its

natural state. The home farm is valued at £490 a year, the grass parks

at £600, woods £100, mansion, lodge, and stables at £215. On the east

side of the mansion and grounds, and including in its centre the station

and village of Carstairs Junction, is Strawfrank farm, occupied by Mr

John Allison. Like all farms in the district, Strawfrank includes a herd

of Ayrshire cows, the milk of which is partly sold to villagers at the

junction, and the remainder sent to Edinburgh or Glasgow. Milk can leave

Carstairs at seven in the morning, and the cost of carriage to either

city is 1d. a gallon, which is paid by the sender. The price obtained

for milk is generally 6d. a gallon in summer, and 10d. to 11d. in

winter; from this the cost of carriage is deducted. In the agriculture

of Strawfrank the six shift is adopted, which consists simply of three

years in crop and a like period in pasture. Of green crop there are

about 30 acres in potatoes and 10 in turnips, which is about the reverse

of the proportion usually adopted in the district. Besides farm yard

manure, guano and dissolved bones are applied to the green crop; oil

cake and pease meal are used as feeding stuffs for cows. No barley or

any grain except oats is grown, and the oats are of the Providence

variety, which is most suitable as being an early sort. The yield will

be 6 bolls an acre in an average year, and the weight 36, 38, to 40 lbs.

a bushel. Potatoes yield 7 to 8 tons of good potatoes to the acre. The

soil of the farm is. much mixed. A large tract north of Carstairs

Junction has been taken from moss, and from being a worthless morass is

now fair soil stocked with sheep and cattle. The whole farm has been

drained, but the tiles get speedily filled up with red iron ore, and in

three or four years require attention to keep them in order. Mr Allison

has fenced and irrigated about 30 acres of meadow close to the railway,

which promise a good return. The house and steading are fair; but a new

lease has been negotiated in a friendly manner this year, and money is

to be laid out in improving the buildings. The factor on the estate is

Mr John Ord Mackenzie, W.S.; and it should be mentioned as indicating at

once a conscientious tenant and the existence of his confidence in the

proprietor and factor that no diminution of manure or other

deteriorating influence was allowed to operate toward the close of the

lease.

In the higher district of the parish Mr Eliott-Lockhart

of Cleghorn, and of Borthwickbrae, near Hawick, has six farms, of which

the best is Harelaw, recently rented at £450 a year. In the moorland

district the soil is a mixture of clay and black earth; the dale or low

land generally sharp, sandy soil; but both divisions are of fair quality

and capable of producing good crops in an average season.

The parish of Lanark has an area of 10,385 acres, of

which the ordnance survey gives 7053 arable, 524 heathy pasture, 629

rough pasture, and 1220 under wood. The valuation is £22,029, 3s. In

1881 the population of the parliamentary burgh was 4909 ; of the royal,

beyond the parliamentary burgh, 951; and of the landward part of the

parish, 1706. In 1871 the numbers were 5099, 715, and 2012. In 1861 the

population of the parish was 7891. Lanark is believed to have been the

Roman "Colonia," a station on Watling Street; and the place where

Kenneth II. held a council in 978, Alexander

I. erected it into a royal burgh, and the privileges conferred by him

were confirmed by Robert I., James V., and

Charles I. During the wars with England, as well as afterwards in the

time of Charles II., Lanark was the scene of

important transactions. The town occupies an elevated and healthy site

half a mile from the Clyde, and contains handsome buildings and good

shops. It unites with Airdrie, Hamilton, Falkirk, and Linlithgow in

electing a member of Parliament. The market days are Tuesday and

Saturday; and fairs are held on the Wednesday before the 12th May for

rough sheep and black cattle, on the Wednesday before the 12th August

for horses, and on the previous Monday and Tuesday for blackfaced,

Cheviot, and cross lambs; and on the Thursday after Falkirk October

tryst for cattle and horses. Races take place about 2 miles from the

town on the day after the Whitsunday fair. A mile from the town is the

manufacturing village of New Lanark, founded about 1784 by David Dale,

who built the first of the present long range of cotton spinning mills,

and constructed a subterranean aqueduct 300 feet long, cut through the

solid rock, so as to utilise the waters of the Clyde. The mill was

purchased in 1799 by a number of English capitalists for £66,000, and

entered on a new career under the management of a son-in-law of Dale,

Robert Owen, to whom the town is indebted for its educational

establishments. In 1814 the business was offered to public competition,

and purchased by Owen, for a Quaker company, at £112,000. In 1827 Owen

ceased to have any connection with the village, and the factory passed

into other hands. In 1873 the New Lanark company was entered as

possessing 274 acres of land at a valued rent of £2318. The parish is

noted in connection with the falls of the Clyde.

In 1772 Pennant wrote of the land near Lanark, "much

barley, oats, peas, and potatoes are raised about the town, and some

wheat." The manure most in use was a white marl full of shells, found

about four feet below the peat, in a stratum 5½

feet thick; it takes effect after the first year, and produces vast

crops. The same writer adds that " numbers of horses are bred here,

which, at two years old, are sent to the marshes of Ayrshire, where they

are kept till they are fit for use." The surface of the parish is hilly.

At New Lanark it rises 600 feet above the sea level, and the moor of

Lanark is 150 feet higher. In some parts the soil is free, in other

places stiff, with a retentive clay subsoil; some of the moor is good

boggy land, other parts are hard heather. A common rotation is oats,

green crop, oats, then hay or pasture, and afterwards four years in