bald,

Overshiels, has long been regarded as a source of pure blood, and good

breeding. A distinguished sheep farmer, writing to us on the subject of

blackfaced sheep, likens them to the favourite tribes of black Polled

Aberdeen or Angus cattle, thus—"I should say of the blackfaced sheep

which are notable for their long standing and superior breeding, that

the Glenbuck stock occupies the position of the ' Ericas,' and the

Overshiels and Knowehead stocks the places of the 'Pridesè and 'Lucys.'"

Other gentlemen who have aided in the improvement of

the breed are Messrs Fleming, Ploughland, Lanarkshire; James

Greenshields, West Town, Lanarkshire; T. Aitken, Listonshiels; James

Craig of Craigdarroch; R. Buchanan, Letter, Killearn; J. Moffat,

Gateside, Dumfries; P. Melrose, Westloch, Peebles; Thomas Murray,

Braidwood, Penicuik; John Sloan, Barnhill, Ayrshire; James Duncan of

Benmore, Argyllshire; William Whyte, Spott, Kirriemuir; Peter Robertson,

Achilty, Dingwall; James A. Gordon, Udale, Invergordon; Donald Stewart,

Chapel-park, Kingussie; and Mr Brydon, Burncastle, Berwickshire.

I have to acknowledge my gratitude to several of

these gentlemen for their valuable assistance, in placing at my disposal

their observations and experiences in connection with the breeding and

rearing of blackfaced sheep. Their communications will not only form an

interesting appendix to my treatise, but they have served in confirming

former opinions. Lanarkshire has from time immemorial been regarded as

the nursery of blackfaced sheep, and this and other southern counties

have played important parts in the resuscitation of the breed. Their

annual sales have been valuable institutions for many years, and have

been the mediums through which a great deal of excellent blood has been

disseminated. Drafts of young tups from the best breeding stocks in

Britain are disposed of at these sales, and the gradual increase of

prices obtained for tups during the past quarter of a century, affords a

good indication of the growing desire to procure pure blood and

fashionable types. The great secret in keeping blackfaces is to avoid

overstocking. The importance of this was sadly overlooked in the earlier

history of the breed, but with the enlightenment of the past fifty or

sixty years this disadvantage has been generally guarded against. The

principal events of the year for breeders of blackfaced sheep are the

Lothian ram sales, the Perth sales, and the autumn Falkirk trysts. At

all these there is generally a good representation of the leading sheep

stocks in Scotland, which country may be designated the home and

fountainhead of the breed. The Lothian ram sale is an important event to

breeders who go in for high-class stock, and we are pleased to note that

these are year by year increasing in number. That they are increasing in

number is well indicated by the fact, that the demand has been gradually

becoming more active for many years, This fact has not been so forcibly

demonstrated within the past few years, but from 1850 to 1876 there was

a very remarkable improvement in the character of the tup market. The

increased fastidiousness of flockowners in selecting highbred tups has

been the means of bringing large prices into the hands of a few of the

most enterprising and successful sheep breeders. The demand has been

pressing for tups extracted from some of the flocks which I have

previously mentioned, and the owners of these may be said to have

enjoyed a monopoly of the trade. The rise in the prices of high-class

stock within the past twenty-five years has been remarkable, and affords

additional evidence of the desire now extant to produce an altogether

finer race of sheep. Tups which were worth about £7 each twenty-five

years ago—and £7 was considered a good price—would now bring from £60 to

£70, while £20 each is not considered a very high price for well-bred

rams. For ewe stock the demand has been less active, and consequently

the advancement in prices of ewe stock has been less marked. Some thirty

years ago, however, 25s. was regarded as a more extravagant price for a

ewe lamb than 50s. or 60s. would be at the present day.

The great advancement thus indicated in the prices of

black-faced sheep has not entirely resulted from one cause. There have

been several agents working with combined force in bringing it about. An

important one of these agents has undoubtedly been the prevailing

anxiety to improve the character of the blackfaced breed, whose natural

characteristics are so well calculated to resist the hardships of a

severe climate. This anxiety has long existed among a few flock-owners,

but it has been gaming a hold upon the majority in recent years, and

extending rapidly. The causes for this are not far to seek or ill to

find. The revolutionary tendency of the wool market, and the

meteorological severity of the past eight or ten years, have turned the

attention of many admirers of finer woolled breeds to the blackface. In

all industries the branches expected to yield most profit are generally

pursued, and it is believed, if indeed not actually proved, that

considering the scanty fare on which this breed subsists, and even

thrives, Highland flocks are on the whole most profitable. What proves

an obstacle to the development of pastoral pursuits in Scotland,

however, is the large extent of deer forests. Fashion is the

all-powerful agent which has been at the bottom of the mania for

creating and extending these. It was estimated in 1873 that the number

of sheep displaced by forests in Scotland was 400,000, while it has been

computed that since then the number of sheep displaced has been raised

to 481,550. The number of forests in 1872-73 was said to be between 60

or 70, and now, including those only partially cleared, the number is

96. Of these 96 forests there are 5 in Aberdeenshire, 6 in Argyllshire,

1 in Banffshire, 1 in Caithness, 5 in Forfarshire, 33 in

Inverness-shire, 5 in Perthshire, 37 in Ross and Cromarty, and 3 in

Sutherlandshire. The total number of sheep in these counties at present

is about 3,363,414.

Many experiments have been tried during the history

of the Highland breed of sheep with a view to the improvement of its

wool. These were conducted in various parts of the south and north of

Scotland, by way of crossing blackfaced ewes with tups of other breeds,

but the results have invariably been disappointing. The experiments

tended rather to degenerate instead of improve the Highland breed. "Some

time is required," says a sheep-farmer, "before the blackfaced stock can

be restored to its natural purity after being crossed with tups of other

breeds." Crossing blackfaced ewes with Leicester rams is a common

practice among flockowners who fatten their young stock for the market.

In these circumstances, such a course is justifiable and commendable, as

it produces heavier and earlier-maturing lambs.

The depreciation of the finer varieties of wool in

the wool market arises from the fact that the demand is being supplied

from other countries. The Cheviot and Leicester breeders are thus being

undersold by their foreign competitors, and the breeders of Highland

sheep would share the same fate, if the wool of the blackfaced sheep had

not a speciality which adapts it for peculiar purposes. Its coarse,

shaggy fibre is found to be more durable and serviceable in the

manufacture of carpets and other rough textures than any other variety

of wool.

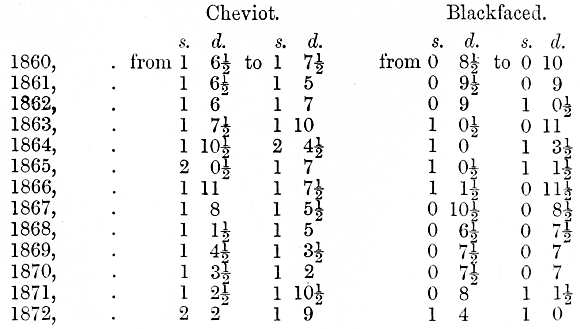

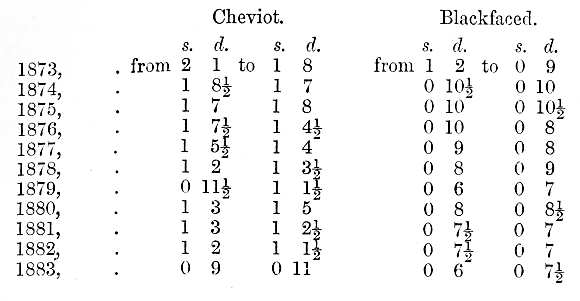

The following is a comparative statement of the

average prices of white wool of both Cheviot and blackfaced sheep since

1860:—

These figures show a great irregularity in the prices

of wool, the result of the fluctuations being a very considerable

decline during the past ten years. It will be observed, however, that in

consequence of the cotton famine and American war in 1864, the prices of

both classes of wool rose materially in value, and continued high till

the end of 1867. Another ascendency took place in 1872, as a result of

the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-71, but since then the variations have

been less marked. The prices of Cheviot wool have been falling more

rapidly than those of blackfaced sheep, which is shown to have been at

as low an ebb as 7d. in some former years, but not within living memory

has the price of Cheviot wool been so low as it now is (1883). In

reference to this subject, Mr Aitken, Listonshiels, says—"Owing to

foreign competition, wool has been selling very cheaply of ]ate, being

nearly as low as it was fifty years ago, the difference being from 1d.

to 2d. per lb. for wool of the best quality. Highland wool in some cases

only brings 5d. per lb., while in 1864 the current price was as high as

1s. 3d.—more than double the present selling rate."

Though for many centuries the prevailing breed in the

mountainous parts of the south of Scotland, the blackfaced sheep were

not introduced into the north until a comparatively recent date. The

Cheviot breed was largely scattered over the northern counties before

this hardy species had passed the Grampians. For at least a century,

however, blackfaced sheep have been in possession of northern farmers,

and within the past twenty or thirty years they have greatly increased.

Cheviots still hold a place in the counties of Caithness, Sutherland,

Ross, and Inverness; but for many years they have been losing ground,

and the Highland breed on the ascendency, both north and south. The

leading promoters of the breed in the north are Mr Robertson, Achilty,

who has a large sheep run attached to his arable farm; Mr Gordon,

Balmuchy; and Mr James Gordon, Udale. These gentlemen are careful in

their selection of tups, and raise equally as good tup lambs as those to

be met with in the south of Scotland. A writer, in describing a tour

from Land's End to John o' Groats, in 1864, made the following reference

to the upper reaches of Strathspey, in which the counties of Perth,

Banff, and Inverness all join:—

"The sheep in this region are chiefly the old Scotch

breed, with curling horns and crooked faces and legs, such as are

represented in old pictures. The black seems to be spattered upon them,

and looks as if the heather would rub it off. The wool is long and

coarse, giving them a goat-like appearance. They seem to predominate

over any other breed in this part of the country, yet not necessarily

nor advantageously. A large sheep farmer from England was staying at the

inn, with whom I had much conversation on the subject. He said the

Cheviots were equally adapted to the Highlands, and thought they would

ultimately supplant the blackfaces. Although he lived in Northumberland,

full two hundred miles to the south, he had rented a large sheep walk or

mountain farm in the Western Highlands, and had come to this district to

buy or hire another tract. He kept about 4000 sheep, and intended to

introduce the Cheviots upon these Scotch holdings, as their bodies were

much heavier, and their wool worth nearly double that of the old

backfaced breed. Sheep are the principal source of wealth in the whole

of the north and west of Scotland. I was told that sometimes a flock of

20,000 is owned by one man. The lands on which they are pastured will

not rent above one or two English shillings per acre; and a flock even

of "1000 requires a vast range, as may be indicated by the reply of a

Scotch farmer to an English one, on being asked by the latter one, 'How

many sheep do you allow to the acre?' 'Ah mon,' was the answer,

'that's nae the way we counts in the Highlands; its how monie acres to

the sheep!'"

Cheviots were then, as already indicated, displacing

the Highland breed in many parts of Britain, but since that time a very

material change has taken place. Even the green mantled hills of the

south are being more extensively put under blackfaces every year. "From

the time of King James down to the year 1785," says Hogg, in his

Statistics of the County of Selkirk, " the blackfaced or forest

breed continued to be the sole breed of sheep reared in this district;

and happy had it been for the inhabitants had no other been introduced

to this day." The latter clause of Mr Hogg's remarks will, we have no

doubt, be very freely re-echoed by many flockowners who have had the

disagreeable experience of changing stocks, as the maxim of supply and

demand required. A writer on the subject, in the year 1844, states that

in the south of Scotland "Lord Napier made strenuous and successful

exertions to arouse and direct the solicitude of sheep farmers to the

improvement of the Highland breed. In the Vale of Ettrick he began

con amove to take and to give lessons on sheep husbandry; and in

1819 he succeeded in forming a pastoral society, which since the date of

its establishment has steadily and successfully directed the energies of

the farmers." "So early as 1798," continues the same writer, "the

majority of sheep walks in the south were stocked with Cheviots, but the

old blackfaced sheep, in the rough character which belonged to it before

the era of modern improvement, was some fourteen or fifteen years ago

reintroduced to two or three farms in the county of Selkirk, but it has

never reacquired favour, or been fairly tolerated, except where the less

hardy whitefaced sheep is too fragile for the abrasions of the climate."

Characteristics of the Breed.

The nature and habits of the blackfaced sheep are

truly Highland. When left for a short time on the hills unmolested it

becomes wild, and wherever depasturing during the day, it has the

peculiarity of returning regularly to one particular spot over night. It

seeks its bed on elevated ground, and it is both pleasant and

interesting to watch its instinctive movements on the hillsides on a

fine summer evening. About sunset it repairs to its sleeping ground, and

in olden times it was regarded as a foretaste of good weather if the

flocks moved early and heartily to their lodging places.

The following are the points which pure-bred tups

should possess:—Long-wool; evenly covered body, with a glossy or silky

appearance; legs, roots of the ears, and forehead (especially of lambs)

well covered with soft fine wool; the muzzle and lips of the same light

hue ; the eye bright, prominent, and full of life ; the muzzle long and

clean, the jaw being perfectly bare of wool; the ears moderately long;

the horns with two or more graceful spiral turns, springing easily from

the head, inclining outwards, downwards, and forward—the upper edge of

each turn being horizontal with the chaffron; the carcase long, round,

and firm ; the neck thick and full where it joins the shoulder; the

shoulder bones well slanted; the limbs robust and chest wide; and the

ribs well curved and full, wool coming well down on the thighs and

chest; face and legs, if not entirely black, should be speckled, and the

hind legs well bent at the hocks, and free

from black spots or "kemps." The general figure of the ewe is the same

as the tup, but the horns should be flat and "open," or standing well

out from the head. Big-boned lanky sheep, with narrow chests and flat

ribs, are generally of weak constitution, and these, as well as sheep

with bare hard hairs on their legs, breast, neck, and face—which are far

too common—ought to be got rid of. On these animals there is a great

proportion of the wool "kempy," or full of hard white hair, and

destitute of felting property. It is observed that sheep with strong or

rising noses are generally hardier in constitution than those with weak

hollow faces. The most objectionable point of the present race of

Highland sheep is the inferiority of its wool. The average yield is as

nearly as possible 4½ lbs. per hogg, 3½

lbs. per ewe, and from 4 to 5 lbs. per wether.

The return, both in quantity and quality, varies in accordance with the

nature of the pasture, soil, and climate on which the sheep are kept. A

higher return is obtained in the south of Scotland than in the northern

counties. Where the sheep are pastured on strong grassy land, the

quality of the wool is finer than when they are confined to heathery

pasture; but the latter gives an additional flavour to the mutton, which

is a favourite commodity in the metropolitan markets. The females of the

blackfaced breed are not so prolific as those of the Cheviot or

Leicester breeds, there being as a rule a return of only one lamb for

each ewe. It sometimes happens, however, that Highland ewes have two

lambs, but in the majority of cases, or in fact in nearly every case,

they give birth to and foster only one lamb. The number of ewes allotted

to each ram varies with the different systems of management, but one tup

has often been known to sire over 60 lambs.

On the better farms in the south of Scotland the

return of wool is considerably heavier than on the northern pastures,

having been greatly improved since the pastures came under the

management of the present tenants. As an instance of this, I may mention

that in 1864, which was a fairly representative year, the average weight

per fleece of ewes and hoggs on Mr Howatson's (Glenbuck) pastures, was 4½

lbs., whereas in 1875 it was 5½ lbs.; in 1876,

notwithstanding the severe season, it was 5¾

lbs., thus showing an increase of 40 per cent. in twelve years. Since

1876 this successful breeder has raised the average yield of wool per

ewe and hogg to about 5½ lbs.

Management of Highland Sheep.

Over the immense tracts of mountainland, which

constitute a large proportion of the entire area of the United Kingdom,

a very efficient system of pastoral farming has prevailed for nearly

half a century. As early as the advent of the present century, many

flockowners in the south of Scotland had begun to give a considerable

amount of attention to the management of mountain pastures, and their

good example ultimately extended to the remotest corners of Britain.

Generally speaking, every large sheep farm is so situated that one part

of it is best adapted for ewe stock; another portion is more suitable

for hoggs; while the more elevated and barren parts are only fit for the

rearing of wethers. One of the points of pastoral farming which has

hitherto been greatly overlooked, and which is now beginning to claim

the well-merited attention of farmers, is the drainage of hill pastures.

This is not only the means of removing many dangerous streams, springs,

and flat swampy bogs, which usually intersects mountain pasture, but it

improves the quality of the grass, and prevents rot and other diseases

which are fostered by wet land. Fencing sheep pasture is a practice not

very extensively adopted, except on small farms where flocks are

confined, and require the constant attention of a shepherd. Boundary

fences are common in some parts of Britain, and these prove

advantageous. It would be of much service if the practice of enclosing

and dividing mountain farms was more generally pursued. It would afford

accommodation for separating flocks as occasion required. On farms on

which breeding is regularly conducted, parks are specially valuable,

though they are not so common as they should be. Besides preventing

sheep from straying, they afford special facilities for keeping tups and

ewes separate, which becomes necessary at certain seasons of the year,

and also for the weaning of lambs.

The southern districts of Scotland claim the honour

of raising the best stock, and as being the districts in which the

spirit of improvement has been longest and most actively at work. In the

counties of Lanark, Ayr, Dumfries, Selkirk, and Mid-Lothian, the

greatest pains and attention have been bestowed on the breeding process

for a long period. The northern counties, though at one time far behind

in their production of stock, have been pulling up within the past

twenty or thirty years. Farmers who had previously been groping in the

dark, as to the "secrets" of successful breeding, have recently been

showing inclinations to vindicate the honour of the Highland fleece. A

most active system of (Highland) sheep farming now exists throughout the

United Kingdom, and we have no doubt but, "with a long pull, a strong

pull, and a pull altogether," farmers will yet acquire a much higher

celebrity for their Highland breed. The selection of tups, and the

"weeding out" of inferior females from the flocks, are now receiving a

considerable measure of that careful attention which these points so

strongly demand and so well deserve.

Tups are generally put to the ewes from the 20th to

the 30th of November,—according to the situation and character of the

farm,—but it is a widely recognised rule on mountain farms that it is

much better, both for the mother and the offspring, to have the lambing

a little too late rather than too early. In the more northern and inland

districts, flocks in the fall of the year are generally sent to be

wintered in the low country or seaboard parts. The character of the

winter on the hills is, as a rule, much more severe than in the low

arable country, and the system of wintering keeps down the rate of

mortality among Highland flocks. About 1860 the average price per head

for wintering ranged from 2s. 6d. to 3s. 6d., but since then it has been

doubled. Six shillings per animal is a common price now; and if a small

extent of turnips is allowed along with pasture, 7s. 6d. or 8s. is

sometimes obtained. Two reasons for this great increase in the expense

of wintering may be put down thus. The first is, that owing to the

increased value of the sheep, owners thereof in upland districts turn

more of them to the low country than formerly, in order to get them as

well wintered as possible. The second is, that many lowland farmers, who

formerly let their winter pasture, now prefer either to keep sheep all

the year round, or to buy them in to winter, with a view to sell in

spring or through the summer season. Between the years of 1830 and 1840,

the cost of wintering sheep was calculated at from 1s. 6d. to 2s. per

head. Hoggs are usually put to the wintering ground about the 1st of

November and taken home about the 1st of April.

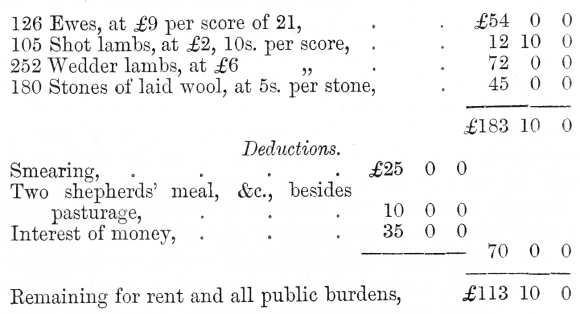

Messrs Kennedy and Grainger, writing in the year

1829, thus compute the profit and loss from a flock of 1000 blackfaced

breeding ewes in Inverness-shire:—

"This sum was considerably short of what was wanted

for the landlord; and the only resources for the tenant, in order to

enable him to make up the deficiency, and keep his family, was the keep

of a few cows, and the growth of potatoes, but which, after all, would

yield a very unprofitable return for the time employed and the capital

invested. The rent, however, is now lowered, and the price of the wool

considerably raised." In the southern counties of Scotland the flocks

are seldom taken off the lower hills during the winter season. About

Christmas the rams are withdrawn from the ewes, and fed upon turnips,

hay, crushed oats, cake, &c. Flocks kept on hill farms during winter

require the close attendance of shepherds, particularly during stormy

weather. Despite the vigilance of the most trustworthy shepherd, the

sheep—having a tendency to crouch in sheltered places, where snow when

drifting is sure to accumulate—frequently become embedded in wreaths of

snow. Heavy losses are sustained in this manner. One of the most

striking characteristics of the blackfaced sheep is its endurance

amongst snow. I have seen cases, during my experience of hill-farming,

of sheep being buried under a wreath for six or seven consecutive weeks,

and coming out alive after a thaw. Frequently, however, after being

subjected to such prolonged confinement, they succumb to the elements

after being set at liberty. The pasture on hill farms generally gets

scant during the winter season, and it is found necesary to supplement

the food which flocks gather on the hills by hay, straw, turnips, &c.

When farmers send their sheep to be wintered in the low country, they

are always careful to place them under the charge of trustworthy and

faithful shepherds. For successful sheep farming a careful shepherd is

the all-important functionary.

In his description of the qualifications of a

mountain shepherd, Mr Little says—"The shepherd should be honest,

active, careful, and, above all, calm-tempered. A shepherd who at any

time gets into a passion with his sheep, not only occasionally injures

them, but acts at great disadvantage both in herding them and working

among them. A good-tempered man and a close-mouthed dog will effect the

desired object with half the time and trouble that it gives to the hasty

passionate man. The qualifications of a shepherd is not to train his dog

to running and hounding, bat to direct the sheep, according to the

nature of the soil and climate, and the situation of the farm, in such a

manner as to obtain the greatest quantity of safe and nutritious food at

all seasons of the year. Those shepherds who dog and force their flocks,

I take to be bad herdsmen for their masters and bad herdsmen for the

neighbouring farmers." These remarks are to the point in every sense of

the word, and cannot be too frequently impressed upon the minds of both

shepherds and masters. At all seasons, interested shepherds can, by care

and judgment, do a great deal in improving the condition of flocks.

Most farmers take a quantity of turnips along with

lowland pasture during the winter, and when the supply of grass falls

short in the first of spring, the sheep are usually netted on the

turnips. This is found to encourage the growth and muscular development

of young stock. Ewes in lamb are sometimes also allowed a supply of

turnips, but if they can be brought through without it there is less

danger of mortality at the lambing season. When ewes, heavy in lamb, are

kept upon such nutritious food, the growth of the horns of the male

lambs becomes so stimulated as to frequently entail the death of the one

or the other, or both ewe and lamb, during lambing. Lambs are often to

be seen among Highland flocks as early as the 1st of April, but farmers

have been taught some costly lessons in recent years, to guard against

early lambing. The hoggs are put to the hills when taken home from the

wintering, but breeding ewes are, as a rule, kept on dry ground near the

farm steadings or sheep cots, in order that the closest attention can be

given them during the critical period. It is customary, when

practicable, to give a few turnips to ewes immediately after Lambing,

and this enriches the supply of milk for the lambs.

Tup lambs are castrated about the end of June, or

when they are eight or ten weeks old. Clipping is begun among hoggs

about the middle of June, and is generally finished about the second

week of July. It is the custom on many farms to wash the sheep before

clipping them. In the shearing operation mutual assistance is frequently

given. Neighbouring shepherds help each other during the clipping. The

sheep are generally branded on the horn or marked with tar or paint at

clipping, while some farmers dip them immediately after the fleece is

removed. The lambs are allowed to remain with their mothers until the

end of July, when weaning begins. At this stage the lambs (but in some

cases the wether lambs are not weaned till later on) are separated from

the ewes and kept on clean pasture, usually preserved for the occasion,

for at least a fortnight, out of hearing of their mothers. Commonly the

"weeding out" process takes place at the weaning season, that is the

singling out of inferior lambs, or technically speaking "shotts," which

are then, or shortly afterwards, disposed of along with "cast" ewes. The

age at which ewes become "cast" is, generally speaking, five years, but

in exceptional cases they are sent to the market earlier. The prices of

"shott" lambs vary from 8s. to 16s., while those of "cast" ewes range

from 16s. to 24s. This year (1883) prices were several shillings a head

over these sums. These are disposed of at the nearest market. Sheep

farmers in the North and West Highlands are largely accommodated for

disposing of their summer drafts by the Fort-William and Inverness sheep

and wool fairs, and the Muir of Ord markets, while the Falkirk trysts

and Lanark fairs are the chief emporiums of southern flockowners. Since

so many extensive districts in the Highlands were cleared of men and

black cattle and converted into sheep walks, immense flocks of

blackfaced sheep—chiefly wethers—are annually disposed of at Doune and

Falkirk trysts, and driven into the Lothians and England, where they are

fed on turnips. A few flockowners, who have a lowland farm along with a

large range of hill pasture, feed the wedder lambs on the lowland farm

instead of selling them at weaning time, and dispose of them in the

spring, or through the following summer.

Practically speaking, so soon as the shearing and

weaning are over and the sheep carefully marked, the ewes, lambs, and

wethers are divided, if necessary, and disposed of according to the

nature of the farm. The old and true proverb, that "shelter is half meat

for sheep," is prominently kept in view, and shepherds are watchful to

move their flocks to sheltered ground during stormy weather. During the

past thirty years the practice of smearing, once so common on hill

farms, has been to a great extent abandoned. Some farmers in the north,

however, still smear their flocks. The great mass of flockowners prefer

to dip their sheep, as will be learned from the opinions of the leading

breeders subjoined. It is found to involve less expenditure, and be on

the whole more profitable than smearing. Most farmers dip their flocks

twice a year. This is regulated by the character of the pasture, whether

wet or dry. On very dry pasture one dipping in the year is—at least for

old sheep—sufficient. Lambs are generally dipped at weaning time, and

again before being sent to the wintering.

Besides the experiments tried with a view to the

improvement of the blackfaced breed, some enterprising gentlemen have

also made some progress in the direction of improving pasture land by

draining and liming, &c. Mr Howatson made an experiment on his property

at Dornel, in the parish of Auchinleck, some years ago, which is worth

being recorded. He took two farms, which had been previously used for

dairying purposes, into his own hands, and having drained and limed

them, he put them under a regular breeding stock of blackfaced sheep.

After a trial of some eight or nine years, however, the experiment

proved unsuccessful and he abandoned it, and let the farms. He found

that a sufficient number of sheep could not be kept to consume the

grass, without the latter getting too foul from their droppings, and not

having a portion of rough pasture to graze upon, the sheep lost a good

deal of their hardiness of constitution, which is a very valuable

feature of this breed; and, moreover, the sheep stock on such land, was

not so remunerative as the dairy cows which had previously been kept

upon it. The experiment, however, was not without its value, as showing

that the class of land is chosen for each distinctive breed of stock

which is best adapted for it. The flocks of this gentlemen are, as I

have already indicated, of the highest and purest breeding. He gives and

gets long prices for tups annually. In 1870 he sold a tup at £60, and in

1872 he purchased one at £50. Mr Archibald, Overshiels, has, in recent

years, had the distinguished honour of obtaining the highest average

prices at the Lothian ram sales. He sold two beautiful specimens to Mr

Howatson, at £71 and £58 respectively in 1882.

Smearing versus Dipping.

Smearing and dipping, though practically two distinct

operations, tend to the same object, viz., the destruction of parasites

peculiar to sheep; they also stimulate and improve the quality of wool,

and conduce to a healthy and muscular development of the sheep. Smearing

is confined for the greater part to the western and northern Highlands

of Scotland, but even in these districts it is now less fashionable than

it was some ten or fifteen years ago. The advocates of dipping, as a

substitute for smearing, have increased in recent years, and the former

process is now all but universally preferred in the south of Scotland.

The advantages of dipping are undoubted, but they are by no means best

exemplified in its effects upon wool. The strength of its utility lies

more in its efficacy in destroying keds and all vermin peculiar to

sheep. To dipping, some people prefer pouring with oil, butter, and

turpentine for hill stock on lowland farms. Smearing entails more labour

than dipping or pouring, and is consequently more expensive. The process

is so elaborate that a man can only smear about a score of sheep per

day. The wool has to be parted at a distance of about two inches, and

the composition inserted to the skin in each "shed" with the fingers.

The smearing composition usually consists of Archangel tar, butter,

American grease, brown grease, and palm oil. A dip, consisting of a

combination of oil and grease, has been considerably used during the

past ten or fifteen years. Smearing is recommended for flocks on the

Grampians and Monaliadh ranges, and the highest parts of the counties of

Argyll and Ross. In respect of the extent to which dipping and smearing

are used, the former undeniably bears the palm. Though the latter

process might be considered more suitable than dipping for certain

climates and situations, its cost is nearly three times that of dipping;

and in view of the present condition of the sheep and wool markets, such

an expenditure is considered by many entirely unnecessary, and is being

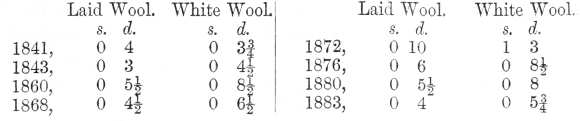

abandoned accordingly. The following is a comparative statement of the

price per pound of white and laid Highland wool at different periods

since 1841:—

Besides the labour which smearing involves, it

depreciates the value of the wool very considerably, and gives rise to

the question, whether the benefit which the sheep derives from smearing

is equivalent to the sacrifice in the price of the fleece by its

application ? The average yield of wool from smeared and dipped sheep is

as nearly as possible thus: Smeared—wethers, 6 lbs. to 7 lbs.;

ewes, 3½ lbs. to 5 lbs.; and hoggs, 4

lbs. to 5 lbs. Dipped—wethers, 3½ lbs,

to 5 lbs.; ewes, 2½ lbs. to 4 lbs.; and

hoggs, 3 lbs. to 4 lbs. These figures show that to make up for the

reduction in the value of laid or smeared wool, there is an increase in

the yield or weight of the fleece over that of white wool. But out of

this has to come the wages of the smearer and the cost of smearing

materials, which together cannot be less than 8d. per head. Dipping is

calculated to cost from 2d to 3d. per animal.

An important and noteworthy fact in favour of the

dipping theory is this, that white ewes, i.e. dipped, or poured,

keep their lambs better than laid ewes. In proof of this an experiment

was tried on the farm of Biallid, near Kingussie, in 1861, by Mr

Stewart. The ewe stock was 2000, 1000 of which were laid with tar and

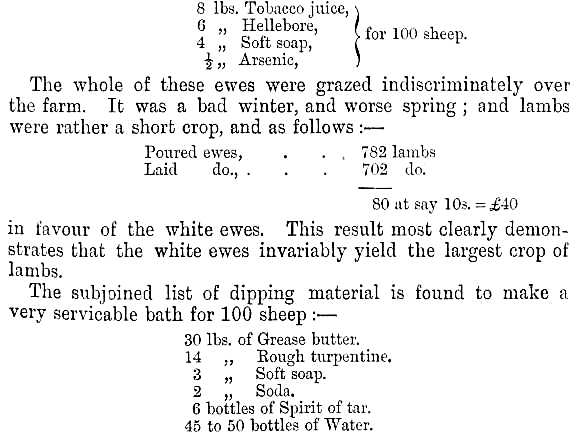

butter and 1000 poured with—

Hints for the Improvement of the Breed.

How can this mountain breed be improved and increased

in value without detracting from its natural hardihood and general

independent bearing ? This question has perplexed the minds of people

engaged in pastoral pursuits for the greater part of a century, but

their past experience has now led to a practical solution of the

problem. With a slight modification of the rough character of the

Highland wool, which has already been effected in some parts of the

country, it cannot be doubted that the blackfaced breed will hold its

own, at all times, against all the other varieties of sheep. It is now

universally admitted that the only means by which this breed of sheep

can be improved or enhanced in value, is by judicious selection and

careful breeding; and with a view to encourage and if possible assist

flockowners in effecting the desired object, I subjoin a few suggestions

which, if carried into effect, I have no doubt will answer the design

for which they have been written:—

1. Select the best woolled tups and ewes of the

blackfaced breed, possessing the most fashionable type—which I have

previously described—of bodies, heads, and horns, from flocks which are

known to contain blood of the purest description, but avoid in-and-in

breeding.

2. Having selected say, five, ten, or twenty ewes,

which come nearest ideal perfection, mate them with tups coming as

nearly as possible to the standard of excellence in every point.

3. Care should be taken that these and their produce

be not allowed to pasture among the ordinary hill stock.

4. Care should be taken that the female progeny of

the first selected lot be not allowed to come in contact with the tups

until they are at least eighteen months old, at which time another tup

will require to be selected, but not from the same source as the sire or

dam of the gimmers had come.

5. This practice of getting a new tup for each

succeeding race should be adopted until the flock would increase so as

to permit a portion of the gimmers being sold. All inferior gimmers

should be disposed of every year, as should also the whole of the ram

lambs.

6. It is specially important that the pasture should

never be overstocked, that the ewes should be kept in good condition

during winter, and that the lambs should not be allowed to fall off in

condition during and after the weaning season.

Appendix.

Mr Howatson of Glenbuck gives it as his opinion, that

the blackfaced sheep are increasing in number, and are deservedly

becoming more popular throughout Scotland every year. The average yield

of wool per animal on his farm is 5½ lbs. per

hogg and ewe. It is a great mistake, says Mr Howatson, to smear sheep ;

it should never be done, and no good farmer will persist in doing it. He

dips his sheep twice a year, at a cost of about 6d. per head. The only

way in which he considers the wool of the blackfaced sheep could be

improved is by procuring the best blood for breeding purposes.

Mr James Archibald, Overshiels, Stow, says blackfaced

sheep farming is now more extensively pursued than it was ten or twelve

years ago. Cheviots were then the favourite breed in many districts, but

in consequence of the very great reduction in the price of wool,

combined with the effects of the recent bad years, that breed has

greatly depreciated in the estimation of sheep farmers. It is actually

dying out and giving place to the hardier blackfaced race.

Writing to us on the same subject, Mr James

Greenshields, West Town, Lesmahagow, says—"Between thirty-five or forty

years ago the blackfaced sheep were very much supplanted by Cheviots,

but a reaction has again taken place, and the blackfaced breed is

rapidly being re-established. As early as the first of the present

century, almost every flock of blackfaced sheep was smeared, but now

smearing is all but unknown. In this district the yield of wool per ewe

is from 5 lbs. to 6½ lbs., the yield per hogg

being 1 lb. more, which is about the average of other southern

districts. Smearing cannot be done at anything less than 8d. per head."

Mr Greenshields has tried some experiments in the crossing of the

blackfaced with other breeds. He has used Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and

Border Leicester tups to black-faced ewes with little success. He

preferred the produce of the Leicester tup, however, to that of any of

the others, as they matured more rapidly, were earlier ready for market,

and fed on scantier fare.

In this district, says Mr Aitken, Listonshiels, and

in the south of Scotland generally, sheep farming is far more

extensively pursued than it was fifty years ago. Blackfaced sheep have

been increasing in popularity during the past quarter of a century.

Their fine hardy constitution enables them to withstand the severity of

the winter and backward summers better than any other breed. The Cheviot

and other breeds are dying out in Scotland. There is most money to be

taken out of black-faced sheep when properly managed, and in recent

years blackfaced sheep farming has been more remunerative than in

earlier periods. South country farmers have become alive to this fact,

and more attention is now being bestowed on the breeding and rearing of

young stock. The average clip on Mr Aitken's farm is 5½

lbs. per animal. Smearing is not practised in his neighbourhood. He dips

his sheep once a year, either in the month of February or October. His

lambs are always dipped at weaning time. The cost of dipping is about

13s. per 100 sheep, or 2d. per head. On soft grassy pasture the quality

of wool is always better than on hard heathery land, but there is great

room for improvement in any case. It cannot be improved, however, by

crossing the blackfaced with other breeds, without impairing the

hardiness and natural characteristics of the Highland breed. The tups

used on all kinds of pasture should have strong shaggy coats, entirely

free from "kemps." The wool must not be short and curly, but, on the

contrary, long and straight in the staple. Mr Aitken considers that the

best way to improve the wool of the Highland breed is to select the best

ewes, whether deficient or not in wool, and mating them with good hardy

well-bred tups. This invariably gives rise to a stock of capitally

woolled lambs. Crossing blackfaced sheep with other breeds, says Mr

Aitken, has always a detrimental effect, and after introducing strange

blood into a flock, it is several years before it can be reduced to a

state of purity.

Mr J. Moffat, Gateside, Sanquhar,Dumfriesshire,says—"Black-faced

sheep at one time, within the past thirty years, threatened extinction

by the growing interest shown in the Cheviot breed, but winters have

been so severe in recent years, that the mortality amongst the latter

mentioned variety has been so great as to necessitate restocking of

farms with the blackfaced or heath breed, whose hardihood is better

calculated to withstand rigorous climates. In this part of the country

it is now threatening to be overdone." Sheep farming, says Mr Moffat,

could be made to pay better by increased liberality on the part of the

landlord in renting farms. The average yield of wool per animal in this

district is about 5 lbs. Mr Moffat holds that there is no profit in

smearing sheep, but on farms where this is practised the average outlay

per head is about 9d. He dips his own flock twice a year, using arsenic

and carbolic acid, which cost about 4s. per 100 sheep.

A gentleman who has been singularly successful in

improving the quality of the wool of his large and superior flock of

black-faced sheep is Mr Robert Buchanan, Killearn. He has also by

careful attention greatly raised the character of his flock ; and

besides having won many distinguished prizes in agricultural shows, he

has obtained high prices for his shearling tups. Not later than the

month of June last, he sold a lot of shearling tups to Mr Malcolm of

Poltalloch, Argyllshire, at £20 each. The only means, he says, of

improving the type of the blackfaced sheep is by careful selection from

the best stocks, and he would suggest the following as the points which

a good sheep should possess:—Strong bone, a good face, well laid-in

shoulder, well set on nice short legs, wool free from "kemps," and

coarse hair. He has during the present year (1883) sold hoggets about

eleven months old at 51s., and he says 45s. is quite a common price when

well fed on turnips and grain. These are extensively bought in by low

country farmers to feed instead of crosses, as they cost generally about

10s. a head less than grey faced lambs.

There has been no smearing in this part of the

county, says Mr Buchanan, for the last twenty years. As a general rule,

it is found that dipping answers equally as well as smearing, and is

much cheaper. Dipping can be performed with half a pound of grease at

say 3d., and dip and men's wages, say 2d.—5d. in all for each animal;

while smearing would cost as much as 1s. a head. He dips his lambs at

weaning time, and again at the 1st of November, when sending them away

to the wintering. Hill ewes are dipped once a year, generally in the end

of October.

Mr William Whyte, Spott, Kirriemuir, corroborates the

remarks of other authorities regarding the popularity of the breed, and

mentions the counties of Lanark, Dumfries, Ross, and Inverness specially

in which the Cheviot breed is being supplanted by blackfaced sheep. The

amount of sheep pasture, however, says Mr Whyte, which has been put

under deer has greatly curtailed the extent of sheep farming. It has not

been paying so well as could be desired of late, owing to the low price

of wool and the cost of wintering. The latter expense has been doubled

within the past thirty years. Wool is selling at half what it realised

some twelve years ago. The clip of well-wintered wethers averages from 5

lbs. to 7 lbs., while that of ewes is from 4 lbs. to 5 lbs. Smearing is

not practised in this county. Mr Whyte dips his lambs when they are

weaned in August, and again in the 1st of October before sending them

away to the wintering. The wool of the blackfaced sheep, Mr Whyte

continues, can only be improved by selecting fine woolled tups of the

same breed, without tampering with crossing. Crossing might be the means

of temporarily improving the wool, but thereby the type and hardiness of

the sheep would be destroyed.

Mr Gordon, Udale, Invergordon, concludes that the

most efficient way to secure and conserve the best qualities of the

blackfaced sheep, as well as to eradicate its defects in a proper and

satisfactory manner, is by careful and judicious selection. He has tried

various crosses, and bred them back to the pure heath breed again, but

without success. The tups used in crossing were those of the Leicester,

Lincoln, and Cheviot breeds, and of what is known as the improved

Lincoln tup, threw the best progeny as regards the quality of wool and

flavour of mutton. The blackfaced breed of sheep, says Mr Gordon, has

always been popular in the central and western counties of Scotland, and

even in the counties of Sutherland, Ross, and Inverness, where, about

the beginning of the present century, it was almost entirely superseded

by the Cheviot breed ; it is again predominant, and has increased

greatly since the heavy mortality among sheep stocks during the severe

winters of 1859-60, 1878-79, and 1880-81.

Mr D. M'Arthur, Elmpark, Helensburgh, a retired sheep

farmer, who had long experience in the breeding and rearing of black

faced sheep, concurs with the remarks of other gentlemen previously

given generally, and adds that by the present laws he does not see how

sheep farming could be made to pay better, except by reducing rents and

fencing hill pasture. The average yield of wool for three-year-old

wethers dipped with grease, is about 7 lbs., that of milk ewes 4 lbs.,

and that of hoggs 5 lbs. a head. Dipping with about half a pound of

grease for each animal costs in all about 5d. a heal.

Regarding these lattar two points, Mr Samuel

Davidson, manager to Lord Tweedmouth at Guisachan, states that the usual

yield of blackfaced wool per animal is 6 lbs. white wool and 8 lbs. laid

wool. It is not profitable, says Mr Davidson, to smear sheep, on account

of the high price of smearing materials, men's wages, and the low price

of laid wool. Smearing costs on an average from 10d. to 1s. per head.

Dipping, says Mr Davidson, is preferable to smearing. It has generally

to be performed twice a year, each dip costing about 2d. per animal.