|

(Quereus Pedunculata et Sessiliflora), in

Scotland.

By Robert Hutchison of Carlowrie.

[Premium.—The Gold Medal.]

Although these two well-known varieties of the

British oak (Quercus Robur) are sufficiently distinct botanically

to be classed as separate species in a report like the present upon the

large and old oaks in the various districts of Scotland, it is necessary

to treat them indiscriminately, and, indeed, as it is not so much the

intention of this chapter of the old and historically remarkable trees,

to present any scientific or botanical description, or narrative of

their physiology or morphology, as to lay before the reader as accurate

and full a catalogue as possible of the many majestic specimens of this

monarch of the woods abounding in its native habitat, it is probably

quite pardonable to treat these two varieties together without

distinction, especially as it has been found extremely difficult to

obtain sufficiently reliable difference in each from the mass of returns

furnished by careful correspondents, whose kindness and trouble in

correctly furnishing minute data of dimensions and other details, it

would be quite unfair to tax by asking further information as regards a

purely systematic botanical distinction. Both varieties are found

growing together in Scotland in their natural condition, and both are

indiscriminately employed for commercial purposes when converted as

timber of home growth. Of the two it may be safely asserted that Q.

pedionculata is by far most generally met with, and the details in

the appendix to this chapter on oaks are mainly occupied with examples

of this variety. Quercus sessiliflora is much more commonly met

with in England than in Scotland, and there are some immense trees of it

in that country, but principally in the southern counties, as, for

example, in many parts of Kent, Sussex, and Devonshire; and on the

authority of Mr Bree, Q. sessiliflora is the almost exclusive

representative of the Quercus family in the lake districts of

England, in Westmoreland and Cumberland.

All former writers on arboricultural topics agree in

allotting the foremost rank, both in point of dignity, grandeur, and

utility, to the oak. Its beauty of outline when fully developed,

combined with its strength, and unyielding resistance to the effects of

the blast in exposed sites, are its chief characteristics of habit

during life; and when manufactured into timber, the wide and almost

universal purposes to which it may be profitably and suitably applied,

are as characteristic of it as are those of it during life which we have

referred to. "It is a remarkable circumstance," as has been well

observed by Sir Henry Stewart, "that the most ornamental tree in nature,

should also be the one the most extensively and strikingly useful."

It is thus seen that although Britain can only lay

claim to two species of the great genus Quercus as truly

indigenous to her soil, while the rest of the family, amounting (taking

evergreen as well as deciduous) to upwards of one hundred and fifty

distinct botanical species, are all of exotic origin, and are

distributed in both hemispheres of the globe, either in temperate zones,

rendered so by their latitudinal position, or in tropical climates by

their elevation,—yet these two are by far the most important, for they

surpass all others not only in majesty of proportions and duration of

life, but also in general utility, durability and strength of their

timber, so that for all uses to which these properties are absolutely

essential, the two varieties (or rather species) of the oak now under

notice, if equalled, are at all events not surpassed by any other tree

indigenous to Europe.

The oak being thus one of the few indigenous

hard-wooded trees in Britain, it appears, from ancient records and

references in old parchment deeds, to have had a very wide distribution

generally throughout the country. Indeed, before the clearing away of

the old forests had commenced in early historical times, it appears to

have been the chief, if not the only, component of these early forests,

and to have covered a very large area of the surface of Scotland.

Sufficient living remnants of these ancient forests still exist, and to

which reference will afterwards be made to show the wide area of the

distribution in Scotland of the oak, while in other districts, where

these natural or self-sown forests have disappeared, or are now only

rarely marked by a few straggling survivors, the remains of -noble and

massive trunks of oak trees are frequently stumbled upon, embedded

sometimes in the alluvial deposits along the banks of rivers, or in

bogs, submerged under deep layers of peat moss, the growth and

accumulated debris of centuries. In this manner, also, many oaks are

found where now no living specimens are to be seen within even a wide

range of the spot, and also where now no oak plantations are to be met

with ; especially near sea-water mark, stumps of large and old trees,

composing aboriginal forests now untraceable, are sometimes found in

situ standing erect, but quite concealed excepting at very low tide

ebb, near river mouths and along some of our coast line. For instance,

at Kirkconnell, Newabbey, Kirkcudbrightshire, some years ago, Mr Maxwell

Witham,—to whose courtesy we are indebted for interesting information

regarding many trees of other varieties in his neighbourhood,— recovered

from the sands opposite his property an "antidiluvian" oak tree,

broken at both ends and measuring 36 feet in length and

14 feet 8 inches in circumference at the middle of the trunk, thus

giving 484 cubic feet of timber. He further informs us that the whole

valley of the Nith at its lower end (about Kirk-connell and Newabbey on

the borders of the Nith, and Newabbey Poer or stream) is thickly

underlaid, at a depth of from 4 to 7 feet, with large oaks, which are

frequently exposed, and brought to light by the shifting of the river

Nith or its tributary streams. In this locality some large and fine oaks

still exist at the present day, and by reference to the appended returns

to this paper, it will be seen that they girth from 14 feet 9 inches to

20 feet in circumference at 1 foot, and from 13 feet 9 inches to 17 feet

6 inches at 5 feet above ground. Other submerged forests—if they may be

so called—of oaks exist on other parts of the coasts of Scotland ; while

in the Highlands, and the more remote northern counties, as well as in

several of the adjacent islands of the Hebrides, oak trunks are fallen

upon in cutting peats where now not a tree is to be seen. Were these

districts, and the Scottish islands generally, therefore, always

incapable of growing timber, as they are too generally supposed and

believed to be at the present day ? The evidence goes to prove that they

were not, and strong grounds for hope may be consequently entertained

that, with perseverance and the introduction of the suitable

descriptions of trees, these wastes may be again, through the energy of

their proprietors, replanted with success. Of course, it must not be

imagined that we advocate the planting, in sea-board situations, of the

oak, for although these remains of former oak forests, of which no

history save their gaunt stumps and fallen trunks now remain, are found

under sands, and even below the tide-mark in various localities, this

may be owing to the variations and upheavals of the beach, to inroads by

the sea upon the land, and to various causes of a similar nature having

altered the relative position of sea and land at the present day, from

what these occupied when these now submerged woodlands waved their

foliage and reared their gigantic trunks in pristine health and vigour.

We find similar traces of early indigenous oak plantations in Scotland

having existed in very remote times in far inland situations and even at

considerable altitudes. For example, at Dunkeld, in Lady Well Wood of

the Athole plantations, and upon a flat plateau in the upper part of the

wood, at considerable altitude, there is a curious formation of the

ground, —abrupt heights or knolls being interspersed with basin-like

hollows,—where, some years ago, in the course of draining these hollows,

the workmen came upon the remains of the trunks of many old indigenous

oaks embedded in the soil. They were of great size, and lay strewed in

one direction, as if at some remote period the whole had succumbed at

one time to some sweeping hurricane which had lashed across the

district, levelling whole tracts of wood before it, the soft nature and

dampness of the site in these hollows making the trees there a more easy

prey to its violence than in drier and firmer soils. Where these remains

interfered with the draining operations they were cut across and allowed

to lie. The wood was still hard and sound and of a black colour.

Of old and remarkable oaks in Scotland noticed and

recorded by earlier writers, several still exist, and have been

identified, and their present dimensions taken, for the purpose of this

report, and these will be found in the tabulated returns annexed. A few

of these early recorded trees may be here referred to, before passing on

to consider in detail many remarkably fine specimens of this noble tree,

not hitherto or only imperfectly noticed by former writers.

The old oak standing north from the Castle at

Lochwood in Annandale, recorded by Dr Walker as measuring, on 29th April

1773, at 6 feet above ground, 14 feet in circumference, and as being

then about 60 feet high, with a fine spreading head exactly circular,

and covering a space of about 60 feet diameter, still exists, though

evincing symptoms of extreme old age. Measured at the same point in

1873, it was found to be 16 feet, having only grown 2 feet in a century.

Measured carefully in October 1879 it was then 19 feet 8 inches at 1

foot;—18 feet 10 inches at 5 feet above ground, and its bole was 12 feet

10 inches in length. In Dr Walker's time this tree was supposed, but

upon what authority is not stated, to have been about 230 years old.

Walker cursorily notices another oak, inferior, he says, to the first

mentioned, growing near it, but in 1773 "measuring near 15 feet in

girth." In 1873 it measured at same point 17 feet, and at 2 feet above

ground it was 19 feet. Of this tree he gives no further details ; but we

find in 1879 that it girthed 24 feet at 1 foot, and 20 feet at 5 feet

above ground, and had a hole of 19 feet 2 inches in length. These trees

are still growing in comparative vigour; they are planted in a good dry

woodland soil at a high altitude, being not less than 900 feet above

sea-level.

The oak at Barjarg in Nithsdale, measured on 15th

July 1796, was 17 feet in circumference close by the ground. At a height

of 16 feet it measured 11 feet 11 inches, at 32 feet

it was 11 feet 7 inches, and at 46 feet from the ground it was 6

feet 8 inches in girth. Dr Walker further states that this tree on 13th

July 1773 measured 16 feet at the ground, and at 16 feet high it was

then 10 feet 3 inches. It had therefore increased 1 foot in hulk at the

base and 1 foot 8 inches at 16 feet from the

ground in these twenty-three years. More recent records of this oak,

undoubtedly the finest in Dumfriesshire even in its decaying state at

the present day, may prove interesting, as showing its waning progress

with the flight of time. In 1810 it was 17 feet 2 inches in girth at 4½

feet from the ground, and in 1879 it measured 19 feet 3 inches above the

conoidal base and 16 feet 3 inches at 6 feet above the ground. The bole

is straight in its timber to the height of 50 feet, and the spread of

the branches covers an area 60 feet in diameter. We have also

ascertained that this tree was measured by a carpenter in 1776, and was

found then to contain 250 cubic feet of timber in its stem. In the year

1762, the Lord Barjarg of that period was informed by some very old

residenters on the estate, that about 90 years previously (1670) it had

been "bored" with the design of cutting it down, if the wood in the core

had been sound. From the hole bored some branches sprouted, one of which

was then (1762) of considerable dimensions. From this it may be inferred

that it had then begun to wane; but it is another instance of very old

trees, which from some circumstance or another, after showing

considerable symptoms of decline, such as hollowness in the stump or in

the branch clefts, again putting on new vigour, and covering over

nature's incipient decay with rejuvenescence and new life. This oak

appears to have long enjoyed celebrity. It was called the Blind Oak of

Keir, [Keir is the

name of the parish in which it is situated.]

and is said to be mentioned by that epithet in some ancient title-deeds

pertaining to the district, written under the shadow of its umbrageous

boughs at least two centuries previous to 1810. It has made two narrow

escapes from being lost to its native county, of which we trust it may

long continue to be the boast, for besides being tested for soundness

with a view to sale as above stated in 1762, its proprietor was, about

the beginning of the present century, offered £30 for it as it then

stood!

Other notable oaks in this district will be referred

to subsequently in this report, when we come to describe specimens not

hitherto recorded by previous writers.

An oak growing on the roadside between Inversanda and

Strontian in Argyllshire was measured on 27th October 1764, and was then

at 1 foot from the ground 17 feet 3 inches; at 4 feet it measured 16

feet 3 inches; and at 15 feet, where the bole divided into branches, it

was 13 feet in girth. It is stated by Dr Walker to have been then in a

decaying condition, and from a careful investigation made in the

district recently, no trace of it has been found, nor can any one be

found who can tell the tale of its fall and removal or subsequent

history. Walker mentions the fact that the remains of many other great

oaks, approaching to the same size, were observed by him in this vale of

Morven, and were all situated among rank heather, in deep peat earth,

lying above banks of mountain gravel. This tree was probably, therefore,

the last survivor of one of Scotland's indigenous oak forests of very

early times in that district.

Another of the early Scottish recorded oaks growing

on the island of Inchmerin in Loch Lomond, has either so altered by its

decay as to be now unrecognisable, or has disappeared entirely. An

examination of the island last year failed to lead to the identification

of "Jack Merin," as this oak was called, although several very

interesting and hoary veterans were found, and are now recorded in the

appended returns. "Jack Merin" stood near the middle of the island

towards the east side, and measured, on 22d September 1784, 18 feet 1

inch. It was then "fresh and vigorous, and remarkable for its fine

expanded head, without any appearance as yet of the stag horns." The

only oak tree now corresponding with the position in the island ascribed

to Jack, is a most magnificent specimen of a short-stemmed spreading

tree. Measured on 15th August 1878, the indefatigable forester who

explored the island to endeavour to identify and measure Jack's

dimensions at that date, reports this tree to be 22 feet 6 inches in

girth at 2 feet from the ground, and divides into several heavy limbs at

4 feet from the ground. He estimated that the bark of this tree alone

would weigh about 3 tons, and that he had nowhere seen such a weight of

oak timber growing from a single trunk. This description is not quite

incompatible with the meagre account handed down to us of "Jack Merin,"

with whose site it corresponds, and although Walker states the soil in

1784 to be "a moorish, weeping soil," this also may hardly be considered

as differing essentially from the soil as stated in 1878, when it was

described as being " deep, humid soil." At all events, if this tree be

not the veritable "Jack Merin" of 1784, it occupies as nearly as

possible the same site, so that if Jack has since " gone aloft," to use

the words of Mr Gordon, who measured this and the other Loch Lomond oaks

in 1878, this veteran must have been his contemporary and neighbour, and

as such deserves notice, as being now, perhaps, the only living witness

of his "ascent"! The next oak in point of size on the island, in 1784

measured 11 feet 2 inches in girth. Such is all the description handed

down to us. Of course, from such meagre evidence it is now impossible to

identify this tree at the present day; but we may give the particulars

here of the only other very venerable and hoary relic of an evidently

far distant century growing near the northern shores of the island. At 4

feet above ground it girthed, in August 1878,

17 feet 6 inches, and at 7 feet the bole divides into three huge limbs,

the two largest of which measure respectively 12 feet, and 6 feet 9

inches in girth. A branch springing from the largest limb measures 9

feet in girth, and the diameter of the spread of branches is 111 feet.

"Several branches of large dimensions appear to have been wrenched off

at various times in its history, while its lean foliage and numerous old

unrecuperated saw draughts tell of its vigour having been spent." Other

large and old oaks still thriving on this island will be found on

reference to the appended returns.

As we have already seen in considering the old

sycamores in Scotland, that many fine specimens are either ascribed to

the planting by the hand of the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots, or as

commemorating eventful incidents in her history; so in like manner, we

find that the oak has also its appropriate patron, many trees in

different parts of the country being called "Wallace's Oaks," and

associated in tradition with incidents in the life and chequered career

of Scotland's great liberator. Sir William Wallace's oak in Torwood near

Stirling, has been in the annals of Scotland immemorially held in

veneration. In this ancient Torwood, it stood in a manner alone, there

being no trees, nor even the ruined remains of any tree to be seen near

it, or that could be said to be coeval with it. The tradition of its

having afforded shelter and security to Wallace when he had lost a

battle, and was escaping the pursuit of his enemies, probably served to

secure its preservation, when the rest of the wood at different periods

had been destroyed. In 1771 it had fallen into a state of advanced

decay, having at some previous date separated clown the middle, and one

half having entirely mouldered away. The other half, however, remained,

and was then at one point about 20 feet in height; what the tree ever

was above this is lost in obscurity. From the peculiar mode of

renovation of old trees already referred to, a young bark had shot

upwards from the root in several places, which had thrown out fresh

shoots developing into branches, towards the upper part of the old shell

of the trunk. This healthy young bark spread like a callus over several

dead parts of the old trunk and over an old arm. It measured then, so

far as the girth of the tree could be estimated from the size of the

half that remained, about 22 feet. It had never been tall, having forked

into several large limbs about 10 feet from the ground, thus affording

at the division a very likely and convenient place of concealment for a

fugitive. From information kindly furnished by the Rev. J. M'Laren of

Larbert, we further learn regarding this historical and interesting

tree. He writes as follows:—"The real Wallace oak is gone for ever. It

stood in what was a part of the Torwood some centuries ago, but the

knoll which it occupied has been long separated from what is now called

the Torwood by ground which has been cleared, and is quarter of a mile

from the present wood.. The old forester (ætat

72), who has lived nearly all his days in the Torwood, cannot remember

ever having seen the veritable tree; but Mrs Stirling of Glenbervie, who

is also of a similar age, remembers well having accompained her late

husband and a young Oxonian, who was filled with zeal about Wallace, to

see the oak, on a bright day in May 1835, and that then the old tree

stump had sent forth a young shoot. Since then the copse has been

rampant, and quite obliterated the old tree. The knoll is still called

'Wallace's Wood;' a small plantation it is, and a field adjoining it,

'Wallace's Bank,' and another field near by is 'Wallace's Kail-yard.'

There is, however, an innocent imposter, which the people about insist

on calling Wallace's oak. It stands within the policies of Carbrook,

close to Torwood, and is evidently some two or three hundred years old.

But though a respectable tree, it is far too young to have been

connected with Wallace." Near the latter tree is an old thorn, which is

called "Cargill's Thorn," from the circumstance that that renowned

Covenanter is said to have stood under its branching head, when he

excommunicated Charles II.

About a mile south-east, close to Glenbervie House,

stands a small but evidently very old oak tree, about 7 to 8 feet in

girth, called the "Jowg Tree," from the fact that a pair of "jowgs" were

in olden times fastened to it for the temporary exposure of delinquents.

There is a tree bearing a similar name at Ochtertyre in Perthshire, and

the appellation is not uncommon in other places.

Another famous "Wallace Oak" grew near the village of

Elderslie, Renfrewshire. In 1825 the trunk of this oak measured 21 feet

in circumference at the base, and 13 feet 2 inches at 5 feet from the

ground. It was then 67 feet high, and the branches covered altogether an

area of 495 square yards. In 1854 this sylvan giant and land-mark of the

past had become the merest wreck of what it was even a few years

previously. Time and the storms of centuries had done their work, but

worse than all, the relic hunters had been unceasingly nibbling at this

once majestic trunk. Little more than a blackened torso then, this oak

remained, with only a few straggling shoots showing any symptoms of

vitality. The dreadful storm of February 1856, completed the

destruction, for by it this grim old sylvan veteran, with thousands of

his less remarkable compeers, was levelled with the dust, Hundreds of

relic hunters in the district, hearing of Wallace's overthrow, hurried

to the spot, and soon accomplished with bowie knife and gully a thorough

dissection of the prostrate hero. Mr Spiers of Elderslie, however,

hastened to the rescue, and had the mangled and mutilated remains of the

trunk conveyed and safely lodged in his residence at Renfrew, where they

have since found a fitting resting-place. Several articles of furniture

have since been converted out of portions of this tree by the proprietor

of Elderslie and Houston, and when a few years ago the foundation stone

of Houston parish church was laid, the mallet used on the occasion was

made from a piece of Wallace's Oak. Two vigorous and thriving oaks in

front of Houston mansion-house were reared from acorns of this famous

tree, and so eager were the inhabitants of the district to secure some

mementos of Scotland's liberator, that some of them even collected the

sawdust in bottles for preservation when the stump was cut up! The

tradition lending interest to this historical tree is, that Wallace and

several followers on one occasion, when hotly pursued by the vindictive

Southerns, found welcome shelter and safety among its umbrageous

foliage.

The largest oak tree of which we have any record in

Scotland grew in the very old oak wood on the north side of Loch Arkeg

in Lochaber, where we learn from Walker, that in 1784 there were many

trees from 10 to 14 feet in girth at 4 feet from the ground. This one,

however, measured at 4 feet above ground in that year, 24 feet 6 inches.

He does not state the condition in which the tree then was, but all

trace of it has now disappeared. From these records it will be observed

that even the largest oaks of which any record has come down to us in

Scotland, probably from the difference of soil and climate, are greatly

inferior in dimensions to the large oaks in Southern Britain; for such

well-known trees as the Wetherby Oak, which Mr Beevor informs us

measured at 4 feet from the ground 40 feet 6 inches,—while there are

others in England which are said to have been still larger,—quite

eclipses those found in our more northern climate. Nor do any of the

remains of indigenous oak forests, found either submerged or embedded in

peat in Scotland, lead to the supposition that their denizens had

attained to greater sizes than those we have mentioned. In

Inverness-shire, at the head of Loch Garry, Sir T. Dick Lauder found the

remains of a prostrate oak forest upon the surface of the solid ground,

among which he found one tree with a clean stem, 23 feet in length and

16 feet in circumference at the butt end and 11 feet towards the smaller

end under the fork. The stock whereon this oak had grown and close to

which it lay, was quite worn away in the centre, and so hollowed out as

to encircle a large and thriving self-sown birch tree of more than 3

feet in girth.

Of other oaks still existing in Scotland, and

remarkable for age and size, but probably little, if in some instances

at all noticed, we find notable examples in a few remaining trees of the

Jed Forest, in Roxburghshire, where there is still to be seen "The Capon

Tree." It is a short-stemmed but very wide-spreading oak, with a

circumference at the base of 24 feet 3 inches. The legend attached to it

is, that it formed the trysting-place for the muster of the border clans

in bygone times; although probably, from its name "Capon"—and of which

there are other trees similarly styled in different parts of

Scotland,—it served another purpose also, having probably been the

selected spot, and under the shade of whose umbrageous head, the early

border chieftain attended to receive the rents or tithes of his vassals,

many of the lands being held of their superior by an annual payment of

fowls, cattle, corn, &c, and frequently we find the reddendo of a

"capon" was a common act of fealty. Not far from the capon tree stands

another oak, probably also a relic of the ancient Forest of Jed. It is

called the King of the Woods, and is a beautiful and vigorous tree, with

a trunk 43 feet in height, and a circumference of upwards of 17 feet at

4 feet above ground. Other interesting old oaks are still found in the

remains of the Caledonian Forest in the park of Dalkeith, in Cadzow

Forest, at Lochwood in Dumfriesshire, and in single trees in many parts

of Scotland. These are given in considerable detail in the appended

returns to this paper, and reference will accordingly now only be

briefly made to some of these of most interest.

The returns contain no examples of oak from

Aberdeenshire, where its presence seems to be somewhat rarer than that

of other descriptions. At Keithhall in that county, although planted in

the most suitable soils and sites, the oak does not appear to thrive.

The soil, too, is a deep loam, which is generally favourable to oaks,

and in the higher parts of the estate it is a light black soil on a

stiff clay or "pan." In Morayshire, along the banks of the Findhorn,

there are a great number of fine oaks, one of the specimens given in the

schedule girths at 1 foot from the ground 27 feet 9 inches, and has

evidently sprung from an old oak stool, for it divides into seven limbs,

which, growing together for about 3 feet from the base, divide, and form

as it were seven separate trees, each limb being the size of a good

useful tree. At Brodie Castle, Morayshire, there are some very good

oaks, growing in a sandy loam soil upon a subsoil tending to clay. One

given in our returns is a very massive tree, girthing 16 feet at 1 foot,

and 12 feet 11 inches at 5 feet from the base. It carries a good girth

well up its bole, which is 35 feet in length. This and the other oaks

returned from Brodie Park were planted between the years 1650 and 1680.

On the estate of Gray, Forfarshire, there is a noble oak tree, supposed

to be about two hundred and fifty years old, and girthing 26 feet 2

inches and 17 feet 2 inches at 1 and 5 feet respectively, growing in a

black deep clayey loam upon a sandy and gravelly subsoil, and containing

by the forester's measurement 623 cubic feet of good measureable timber.

Upon Lord Mansfield's estate of Innernytie la Perthshire, in the

Craigbank Oak Wood, in a secluded dell on the brink of the river Tay,

stands a venerable aged oak, which has hitherto escaped the notice of

the arboriculturist, and judging from its ancient appearance, there

seems no reason to doubt that it has weathered the blasts and tempests

of at least five hundred winters. At 5 feet above ground it measures 20

feet 10 inches in girth, and is still growing vigorously, and making

wood annually. Many other magnificent oaks throw a mantle of hoary and

honoured antiquity around the woods and policies of the royal palace of

Scone. Near the two-mile stone from Perth, near Balboughty plantation,

stand three fine specimens, which are remarkably large for their age.

The first two (see returns) are Quercus sessiliflora, and the

other Q. pedunculated The first were planted in 1808, and the

other a year later. Measured in August 1878, the first has a fine bole

of 56 feet in length, and is 80 feet high. It girths 5 feet 7 inches at

5 feet above ground, and contains 76 cubic feet of timber. The second is

about the same height, is 7 feet in girth at 5 feet, and has 93½

cubic feet of timber. The third (Q. pedunculata) has a clear bole

of 57 feet, girthing 6 feet 11 inches, and contains 114 cubic feet of

timber. In the policies at Scone, near the river Tay, and in a hollow,

stands a majestic wide-spreading oak, planted by King James

VI. of Scotland and I. of England. The

diameter of the spread of its branches covers 75 feet. It is now 55 feet

in height, 15 feet 3 inches at the base, 14 feet 2 inches at 3 feet, and

13 feet 4 inches at 5 feet from the ground. Not far distant stands a

sycamore, also planted by the same monarch, and girthing 12 feet 3

inches at 4 feet from the base. North of the old Scone burying-ground,

in which are some stones of the early part of the fifteenth century,

including that of Alexander Mar, sixteenth Abbot of Scone, who

flourished when the battle of Flodden was fought, is an oak of great

symmetry and vigour, planted in 1809. It is now 70 feet in height, with

40 feet of straight clear stem, and is at the root 10 feet 4 inches in

girth, and 8 feet 4 inches at 5 feet. Although at Castle Menzies the

soil is light, and resting on pure gravel or sand, at no great depth,

there are some fine oaks. In our returns, two specimens are described

which grow there. The first is near the pond, and is a noble tree,

girthing 15 feet 6 inches at a foot, and 12 feet at 5 feet from the

ground. This tree is 70 feet in height, and but from the fact that it

has had one large limb near the top broken off some years ago,

would have been much taller at the present day. This untoward

accident befel it in 1858, which was in the district a very late and

backward season, snow falling heavily before the leaves had been shed.

The superincumbent weight of snow on the topmost branches and foliage

broke off many branches about Castle Menzies policies, and sadly

disfigured some of the fine trees there. At the east gate of the park of

Castle Menzies stands a remarkable oak (see returns). The peculiarity of

this tree is, that it presents on one of its large limbs, about 25 feet

from the ground, a curious branch about 6 feet long, with pure white

foliage, densely matted and quite distinct from all surrounding and

adjacent branches. The white variegation, though completely local, is

very persistent, and has continued now for years. The interest in this

odd freak of nature is further increased by the presence (gradually

disappearing) of an old bell, which, in former times, was suspended

between two of the limbs, but which is being stealthily and quietly

overgrown, and embedded in the development of the limbs, and must ere

long be entombed in its living sepulchre ! But in no part of the

tree-growing and tree-loving county of Perth are better examples to be

found of the oak as well as of other hard-wooded trees than at the

Athole woods surrounding Dunkeld. Although the ancient forest of Birnam

Wood has never quite recovered the famous march of its ancestors to

Dunsinane, many thriving plantations are rapidly clothing the hillsides,

while still a few remnants of the old aboriginal trees, and others

planted fully two centuries ago, remain to testify to the magnificent

proportions of those early plantations, which in the course of time and

nature have gradually given way to younger followers. Near the river Tay

at Birnam, and behind the hotel, may still be seen two immense trees, an

oak and sycamore, popularly credited as being the sole remnants of that

celebrated forest. Both are in full foliage and green vigour at the

present day, and likely to live for many years to come. The sycamore

having been already noticed in the foregoing chapter on that tree, we

now briefly refer to the oak. It is 19 feet 7 inches in girth at 5 feet

from the ground, and grows in a good deep alluvial loamy soil, on gravel

subsoil, quite close to the river Tay. Other remains of decayed oak root

stumps have been frequently found in the vicinity, no doubt relics of

that great primeval forest which so disturbed the peace of Macbeth.

Within the Dunkeld policies are many large and interesting examples of

oak trees, and of these we are able, from personal observation, to give

a few records. In the "King's Park" in the policies at Dunkeld, an oak

flourishes near the river side which girths at its narrowest point, 4

feet from the ground, 15 feet 2½ inches, and

at 3 feet from the ground, it is 15 feet 8½

inches in circumference. It has a fine bole of 12 feet, and then

branches into five huge limbs, each of them being the size of any

ordinary tree. Its spread of branches measures 99 feet in diameter. On

the opposite bank of the Tay from the point where this oak grows, is

seen the famous oak under whose kindly shade the celebrated Neil Gow was

in the habit of retiring with his violin, and where tradition reports he

composed some of his finest pieces. This tree is pointed out as "Neil

Gow's Oak."

"Famous Neil,

The man that played the fiddle weel."

This celebrated fiddler died in 1808, in the romantic

little hamlet of Inver, not far westward from the site of the oak now

identified with his name and fame in song. Another magnificent specimen

of the Quercus pedunculata at Dunkeld is given in our returns,

and is very characteristic of the growth and habit of this variety under

favourable auspices. Another picturesque oak at Dunkeld stands on the

terraced bank on the opposite side of the Tay to "Neil Gow's Oak," and

in full view of that tree. It is called the "Duke and Duchess Oak." It

is a huge massive stump, 16 feet in girth, dividing into two large limbs

quite near the ground, the cleft being fitted up as a seat. It is

evidently a fresh growth from one of the aboriginal oaks of the

district. The grounds of Moncrieffe and Moredun Hill, Perthshire, are

rich in old and stately hard-wood trees, and amongst these are many fine

oaks. One comparatively young tree of great promise and vigorous habit

may be noted. It was planted in January 1822, on the occasion of the

rejoicings in connection with the natal day of the late Sir Thomas

Moncrieffe. It stands in the centre of the fine old avenue of beech

trees already referred to in the chapter on that tree, and is surrounded

by the small Druidical circle which had existed there long prior to the

planting and laying out of the grounds. It is now 72 feet in height,

with a remarkably tall, straight, and clean bole, and is 10 feet 6

inches in girth at 1 foot, and 8 feet 4 inches at 5 feet from the

ground. In cursorily noticing the many fine specimen trees in

Perthshire, we must not omit to notice those at Methven, where there are

some splendid examples of the oak as well as of other descriptions.

Especially to be noted is the "Pepperwell Oak." It stands in the park in

front of the castle, and is said to derive its name from its proximity

to a refreshing spring so called. This tree is noticed in the New

Statistical Account of the parish published in 1837. It is therein

described tree of great picturesque beauty, and contains 700 cubic feet

of wood. The trunk measures 17½ feet in

circumference at 3 feet above the ground, and its branches cover a space

of 98 feet in diameter. It has attained an increase of girth of 3 feet

since the year 1796. In the year 1722, 100 merks Scots were offered for

the tree, and tradition reports that there is a stone in the heart of

it, but, like the Golenas oak, it must be cut up to ascertain this." In

1867 the tree girthed 21 feet 7 inches at 1 foot from the ground, and 19

feet at 6 feet from the ground. It has, however, considerably increased

in bulk since these measurements were taken, and is now at 1 foot from

the ground no less in girth than 23 feet, and at its narrowest part,

about 5 feet from the ground, it girths 19 feet 5 inches, being thus 2

feet more at this point A

count in 1837. It stands by the side of a steep bank, so that the

length of the bole is somewhat irregular. On the higher or upper side,

it measures only about 8 feet in length, while on the lower it is nearly

12 feet long. Four immense limbs spring from the bole, and a fifth was

wrenched off several years ago. This tree is about 80 feet in height,

and is positively known to be at least four hundred years old. An

interesting relic of the old Strathallan Forest remains there in the oak

given in the returns. This tree is called "Malloch's Oak," from the

tradition of a man of that name having been in olden times summarily

hanged upon it for storing up and hoarding meal during a time of

scarcity. There is still extant the contract of the sale of oak trees in

the Castle Wood, where this tree stands, and in which "Malloch's Oak" is

strictly reserved. This document is two hundred years old. The tree must

then have been a familiarly known old tree, and it is popularly supposed

to be from five to six hundred years of age. It is much decayed on one

side, but still flourishes in a green old age, the decayed part, which

is at a point where a large limb has at one time been taken off, being

plated over with iron. It girths 19 feet at 1 foot, and 14 feet 8 inches

at 5 feet from the ground. A large horizontal limb, which may have

formed a very convenient gibbet if the legend be true, extends 56 feet

outwards from the trunk, and is now supported by two posts. Not far from

this tree another remarkable and noteworthy oak grows in "the birks of

Tullibardine," near the spot where the old castle of that name stood.

Tradition reports that under this tree, which is known by the name of

"The Chair Tree," the family of Tullibardine, in feudal times, dined and

held high revelry on special occasions. It is surrounded by a ring of

earthwork resembling an old "feal dyke," which is 28 yards in

diameter, and in this circus arena it is said the castle horses were

formerly trained and exercised. It girths 17 feet at a foot from the

ground, and carries this circumference throughout nearly the entire

length of its bole, which is 20 feet high. It is apparently not so old

as "Malloch's Oak," but apparently also an old "Forest" relic. Near the

roadside on the property of Dollerie, and near the right bank of the

river Turret, about a third of a mile above its junction with the river

Earn, stands a remarkable oak called "Eppie Callum's Oak." The head is

wide for its height, and the trunk is very round. It girths 19 feet 8

inches at 1 foot, 15 feet 10 inches at 3 feet, and 15 feet 3

inches at 6 feet above ground. The legend of the name of this free is

that a certain "Eppie Callum," who lived at the place, planted an acorn

from some celebrated oak in an old teapot (she must have been a

civilized old woman for her day), and when the acorn had produced a

rather inconveniently large young plant she planted it, teapot and all,

in her kailyard, which occupied the spot at the roadside where the tree

now stands. The story will only be verified by futurity, when the oak

comes to be removed, and the remains of the veritable teapot are found

embosomed in its trunk ! On an oak in the vicinity on the Crieff and

Comrie highroad, just opposite Ochtertyre West Lodge, there is a very

curious growth or huge wart-like excrescence on an oak tree, worthy of

note from its size. It is spheroidal in shape, slightly oblate, with a

short axis in supporting branch,—inclination of branch about 45 degrees,

girth of the branch 14 inches, and girth of the growth at its widest

circumference 6 feet 3 inches.

The oaks in the returns from Glendevon, Perthshire

(900 to 950 feet altitude), and from Moreland, Kinross-shire (900 feet

altitude), are good specimens for so high a site above sea level, and

although the oak is thereby seen to develop less timber-bulk at such a

height than in lower situations, it is proved to grow timber there of

fine quality, and the constitution of the tree for hardihood to exposure

is satisfactorily tested.

The many districts in Perthshire, besides Athole and

Dunkeld already referred to, where buried trunks of huge oaks have been

found and exhumed, all point to the inference that its entire area, and

that of neighbouring shires also, was at an early period one huge

impenetrable forest. In the days of the aborigines such vast forests

extended all over Scotland, giving to the inhabitants, indeed, their

name, for Caledonia originally means the country of "the people of the

coverts." These native forests appear to have consisted principally of

fir, birch, and oak. In Balquidder large stumps and trunks of a defunct

forest of oak are frequently found. In Strathtay fossil wood is often

met with, and in the gardens at Murthley Castle, from the bottom of a

lake in the American garden, several large oaks have been discovered

above 6 feet in girth. Remains of birch, alder, hazel, were also found

in a tolerable state of preservation in this lake bottom. Glen-more, a

narrow valley in the parish of Fortingall, was in early times part of

the extinct Forest of Schiehallion; and for a long period the stumps of

fir trees, and large trunks of oak, furnished the inhabitants of the

district with a profitable product,—the fir being used as fuel, when it

is stated to have "emitted a light more brilliant than gas," while the

oak wood, on being dried and exposed, proved so hard as to be

manufactured into sharpening tools for scythes which were readily

marketable. In the bed of the Tay frequently large oaks have been found

in situ, and in good preservation.

But returning from this digression, and having in

considerable detail noticed the remarkable oaks of Perth and the more

northern districts of Scotland, we hasten briefly to direct attention to

the trees in other counties further south. At Tullibody House,

Clackmannan, there is a very handsome oak of immense trunk, girthing 21

feet 11½ inches at 1 foot, and 18 feet

3 inches at 5 feet from the ground. It is acknowledged to be by far the

largest tree of the kind in the parish and district around. This tree is

quite vigorous, and has grown 7 inches in girth at 3 feet from the

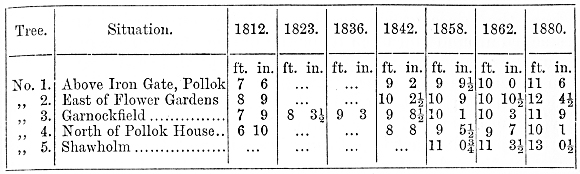

ground since October 1870. The oaks at Pollok, in the parish of

Eastwood, Renfrewshire, are notable examples, and have been carefully

measured from time to time since 1812, and the following results of

their growth ascertained at 5 feet above ground.

Ayrshire can boast many fine examples of the oak, and

there also it appears to have flourished at a very early period in great

luxuriance and forest grandeur. In Galston parish, in that county, good

trees appear to have covered the area of the country at a remote age,

and many fine specimens exist at the present day. An oak trunk was some

years ago found embedded in the ground, about 500 feet above sea level,

having a straight massive bole, 48 feet in length and 10 feet 6 inches

in girth at its upper extremity. Lanfine

Woods, Barr Castle, Cessnock Castle, Auchans Castle, Loudon Castle and

woods, Auchinleck, and Sorn Castle still maintain, by their many lordly

trees, the reputation of the county.

In Lanarkshire there are many interesting and

remarkable old oaks. We may first notice "The Pease Tree," growing on

the estate of Lee in the parish of Lanark. It stands in a hollow,

originally the outlet of the burn or rivulet, which has formed in the

soil and subsoil a deep ravine, or gill as it is locally termed.

The soil is a medium loam with beds of sand and gravel resting on the

usual sandstone, shale, &c, of the coal formation. The trunk of this

veteran is now quite hollow, and, at the height of about 8 feet from the

present surface of the ground, forms itself into three branches,

girthing respectively 16 feet 8 inches, 15 feet, and 11 feet 4 inches.

Parts of these massive limbs are more or less decayed, and standing

boldly out as they do, weather-beaten and divested of their bark, from

amongst the living branches when clothed in their summer greenery, give

to this noble tree a reverential dignity and grandeur well befitting an

artist's study, and carrying the mind of the beholder back through long

centuries of changes and revolutions which have taken place

in the history of Caledonia, since the genial sun and rains first

called forth the nature-sown acorn to send down its tiny rootlets into

mother earth. "The Pease Tree" is said to be one of the few remaining

scattered remnants of the great Caledonian Forest, which stretched

across the centre of the lowlands of Scotland from Ayrshire to St Abb's

Head on the German Ocean, and in which it is said the Roman Emperor

Severus kept 50,000 men for seven years cutting down trees, in order to

prevent the forest affording shelter to the natives. The name "Pease

Tree," is popularly and locally believed to have been given to this tree

from the pease grown on the adjoining farm being annually stacked around

and upon it for the purpose of being winnowed; but the name more

probably derived its origin from the situation in which the tree grows,

from paes or pis, an old British word signifying a rivulet

or spout. Tradition says that Oliver Cromwell and a party of his

followers dined in the hollow part of the trunk, and also that in a

former era a lady of the family of Lee was in the habit of plying her

spindle and distaff there. It is satisfactory to record that this

venerable tree appears to be growing more luxuriantly than it did some

years ago, from the fact that an oak was planted merely to occupy its

place when the hand of time or the blasts of winter should have

completed their work. This tree is now 7 feet in girth at 3 feet from

the ground, and the entrance to the hollow butt of the old tree is

yearly growing smaller, so that in a few years a man will have great

difficulty in getting an entrance. The dimensions of this remarkable

tree are as follows:—Height 68 feet; circumference at 1 foot 28½

feet, at 3 feet 23 feet, and at 6 feet 28½

feet. It appears to be Quercus sessiliflora, while the oak

planted to occupy its place is Quercus pedunculata. The most

interesting and important groups of old oaks in Lanarkshire are the

trees remaining in Cadzow Forest, near Hamilton Palace. The forest is

the property of His Grace the Duke of Hamilton, and lies in a gently

sloping position towards the north. The two enclosures now known as the

Lower and Upper Oaks, the former containing 70 acres, the latter 83

acres, form together part only of the old forest, because adjoining

these remains on the south and west are old pasture fields and

plantations, surrounded by a stone wall 6 feet high and about 3 miles in

extent, which was most probably the boundary in feudal times, when

Cadzow Castle was the scene of many stirring and knightly events. On the

east side the forest is bounded by the river Avon, and on the left bank

of this river are the moss-covered crumbling ruins of Cadzow Castle. The

soil is admirably adapted for the growth and development of oaks, being

a clayey loam resting on a subsoil of clay. In some places the trees

stand quite close together, while in others they stand singly, or seem

to surround large open patches covered with rich natural pasture, on which the famous breed

of native wild white cattle browse, and form an appropriate association

with this ancient relic of Caledonian forest life. The principal

characteristic of all these trees is their shortness of stature,

combined with great girth of trunk. The dimensions of ten of the largest

and best specimens are given in the appended returns. Most of the trees,

and even the healthiest amongst them, are fast hastening to decay. No

planting, pruning, nor felling is allowed within the forest. Tradition

states that these oaks were planted about the year 1140, by David Earl

of Huntingdon, afterwards king of Scotland; but this cannot be looked

upon as a fact, for their appearance and habit clearly point to their

self-sown existence, and, moreover, in the remote period assigned to

them by the legend, little if any attention was paid to the planting of

trees, and the clearing of the native forests was held in far higher

importance than the planting of them.

Another interesting remnant of the old Caledonian Forest still

exists in Midlothian at Dalkeith Park. This portion embraces 130 acres,

and has been most carefully preserved for centuries, its hoary and

gnarled giants being still fresh and vigorous, and likely to flourish

for generations to come. The survival of this ancient tract of woodland

is all the more to be prized when it is recorded that, about one hundred

and fifty years ago, the then owner of the ducal demesne had determined

that the trees should be cut down, and accordingly most of the old trees

still standing were marked for the axe, but by the sudden death of their

owner, the intended improvements were stayed, and the forest thus

providentially escaped annihilation. The mark or "blaze" then cut on

the sides of the trees in the course of years healed over, and became

invisible, but its position is still distinctly seen upon the rugged

bark of these hoary monarchs after the lapse of a century and a half;

and the figures scribed on the "blaze" in lotting and numbering the

trees were still quite legible upon the removal of the superimposed

bark, in cutting up one of the trunks recently blown down. The

dimensions of the "King of the Forest," the largest survivor in the

group, are given in the appended returns. Many other trees closely

approach this monarch in size,—some of the specimens having straight

clean stems, others having no hole to speak of, and all with rugged,

swollen, and curiously knotted trunks, with fantastically twisted,

gnarled, and contorted gaunt-like arms and branches. The timber of these

trees is remarkably rich in colour, and beautifully grained, and even

trunks blown down—no felling being permitted—fetch high prices, so

eagerly sought after is their timber by cabinetmakers for decorative

furniture.

Remains still may be traced in Selkirk and Peebles-shires of the old

Ettrick Forest, which formed another division of the great

Caledonian Forest. In the still richly wooded lands of

Castlecraig, Dalwick, and Posso, in reclaiming land, oak trunks are

still dug out, and are found strewn together as if they had been

overthrown by some flood or angry tempest. The

remarkable oaks at Lochwood, and in other places in Dumfriesshire and

south of Scotland, have already been noticed, and reference to others of

equal interest may be permitted to the appended returns; but before

concluding this report on the old oaks of Scotland, it would be

unpardonable if we did not notice one still existing at Moffat, and

interesting from the fact that we owe its existence at the present day

to that eminent and enthusiastic tree-lover, whose early records and

notices of trees we have so frequently quoted and referred to. This tree

stands upon a slope on the west side of the Annan, near the Dumfries

road, to the south of Moffat. It is a fine old oak, massive, knotted,

and gnarled, with wide-spreading branches, and head finely foliaged in

summer. It is called "The Gowk Tree," and Dr Walker, with true affection

for its associations, in the early part of this century secured its

preservation by a considerable money payment, when the whole of the

forest trees on the bank were cut down by the curators of the Marquis of

Annandale, because it was in that tree the cuckoo annually first

heralded the advent of spring in the parish. Although it lost a great

limb about twenty-five years ago,—almost as large as many a well-grown

oak tree,—it is still fresh and vigorous.

The returns appended to this report will be found to

describe the particulars of many trees which have not been referred to

in this paper, nor, indeed, previously recorded at all; they are stately

and noble specimens, in their different localities, of "the forest's old

aristocrats," each of which

"Takes back

The heart to elder days of holy awe.'

To give a detailed account, or even to name the

various oaks in England, remarkable for their size or for their

historical associations, many of which still exist, would occupy more

space than the limits of a chapter devoted to the old remarkable oaks in

Scotland would allow; but it may render this chapter more complete if a

brief reference is made to some of the most important of them. They are

" full of story, and haunted by the recollections of the great spirits

of past ages." In Norfolk, "the country of oaks," is still to be seen

the ruined relic of Winfarthing oak, which in 1820 is said to have

measured "70 feet in girth at the root and 40 feet in the middle." It is

said to have been known in the time of the Conqueror as "the Old Oak,"

and its age is popularly believed to be over 1500 years. The largest and

oldest oak tree in Windsor Forest, "the King Oak," measures 26 feet in

circumference at 4 feet from the ground. "The Great Oak" of Thorpemarket,

still in healthy vigour, but evincing great age, girths at 1 foot from

the ground 22 feet, and has a bole 42 feet in length, and is 70 feet in

height. In Kent, "the Majesty Oak," at Fredville, girths 28 feet 6

inches at 8 feet above ground. In Nottinghamshire, "the Parliament Oak"

in Clipstone Park, is 28 feet 6 inches in girth at 4 feet from the

ground. Under this tree, in 1290, Edward I. held a parliament, whence

its name is derived. "The Shelton Oak," near Shrewsbury, still exists,

and is fully 26 feet in girth at 5 feet from the ground. This tree is

celebrated from its having been climbed by Owen Glendower on 21st June

1403, that he might reconnoitre the battle of Shrewsbury on his arrival

with supports. In Bagot's Park, Staffordshire, is a majestic oak tree,

28 feet in girth at 5 feet from the ground. The celebrated "Cowthorpe

Oak" in Yorkshire, said to be the largest tree in England, still lingers

on in hoary grandeur. Near the ground the stump girths no less than 78

feet, while it is 48 feet in girth at 3 feet above ground. It is quite

hollow—in fact a mere shell, uncared for, and tenanted by cattle in

their quest for shade or shelter. Eighty-four persons are stated on one

occasion to have stood within its hollow trunk, and it could have

accommodated a considerable number more. Many fine majestic oaks still

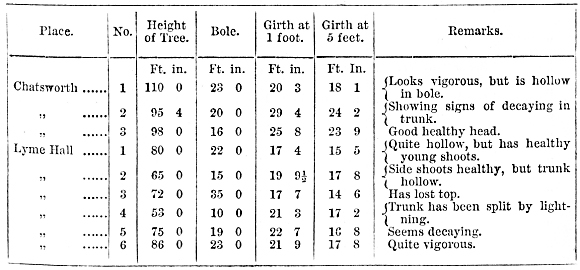

thrive at Chats-worth, in Derbyshire, and at Lyme Hall, in Cheshire.

These are relics of the old High Peak forest. Some of the measurements

made by us in 1876 were as follows:—

These data may be interesting, as the trees last

referred to do not appear to have been hitherto recorded.

In conclusion, we would merely refer those interested

in comparing the other remarkable oaks in England with those we wave

herein recorded in Scotland, to the interesting and valuable Pages of

the Amoemtates quernoa of the late Professor Burnet, in which the

historical facts, legends, and traditions connected with the history of

individual oaks of ancient date are fully given.

Appendix

|