|

By Archibald M'Neilage, Junior, Glasgow.

[Premium—Twenty Sovereigns.]

The county of Bute, composed of seven islands dotted

over the Tilth of Clyde, offers peculiar attractions to men of science.

Containing as it does that

"epitome of the geology of the globe" —the

island of Arran—it is little wonder that it should long ere now have

claimed the attention of the votaries of geology and botany. The flora

and natural history of Arran have often been written of, and few

islands, otherwise so insignificant, have received so much attention.

Bute has formed the retreat of many whose names are as household words

in the world of art. Here Montague Stanley lived and died. Here Edmund

Kean fled for repose from the plaudits of the metropolis, and Glasgow's

merchant princes have many of them spent the evening of their days amid

the salubrious airs of Rothesay, Port-Bannatyne, and Ascog. Bute has

given a premier to Great Britain before now, and Arran is associated

with the traditions of the stirring times of the Reformation and the

Covenants. Indeed, it must be admitted that the county of Bute presents

greater attractions to the man of science, the archaeologist, and the

historian, than it does to the agriculturist. A region dear to artists

and tourists is not generally much accounted of by the practical farmer.

Winding ravines, frowning precipices, and rugged mountain slopes are all

very fine to look at, but are of little avail towards raising good

crops. Nevertheless, the agriculture of these islands is not without a

history, and such as we know it to be we will lay it before the reader.

The position occupied by Bute amongst the counties of

Scotland is unique. Everyone has heard the story of the Cumbrae minister

who prayed for the wellbeing of the "inhabitants of the Greater and

Lesser Cumbraes, and the adjacent islands of Great Britain and Ireland."

No part of the mainland is included in Buteshire, and the islands of

Bute, Arran, the Greater and Lesser Cumbraes, Inchmarnock, the Holy

Isle, and Pladda, form the county. The whole lies between 55° 32' and

55° 56' N". lat., and 4° 52' and 5 º

17' W. long. According to the agricultural returns for 1879, the total

area of the county is 143,997 acres, and the total acreage under crops,

bare fallow, and grass, at the same period, was 24,986 acres, being 72

acres less than in 1878.

Few parts of Scotland, considering its size, offer

such a variety of landscape scenery as this county. Viewed from the

north one sees in front the island of Bute lying long and flat along the

waters of the firth, while in rear of it there rises with overshadowing

vastness the rugged peaks of Goatfell in Arran. The remarks in this

paper made on Bute must be considered as applicable to Inchmarnock and

the Greater Cumbrae, and those made on Arran will apply to the Holy Isle

and Pladda. The Lesser Cumbrae contains 700 acres; it is owned by the

Earl of Eglinton, and, although included in the county of Bute for

parliamentary purposes, it forms part of the parish of West Kilbride in

Ayrshire. Its geological formation is Secondary trap, which seems to

rest on a substratum of brown sandstone. The cultivation is confined to

a few patches growing potatoes and the ordinary garden produce. A great

number of rabbits are reared on the island; but, in fact, the Lesser

Cumbrae with the other two small islands— Pladda and the Holy Isle—may

be said to derive all their importance from the fact of lighthouses

being erected on them.

As the modes of agriculture pursued in Bute and Arran

differ in many particulars, and the prices of the farm produce in each

are ruled by different markets, we think it better to treat of the two

islands in separate sections, and to detail the progress of farming in

each under distinct headings. In order, however, to give an idea of the

agricultural progress of the whole county during the past twenty-five

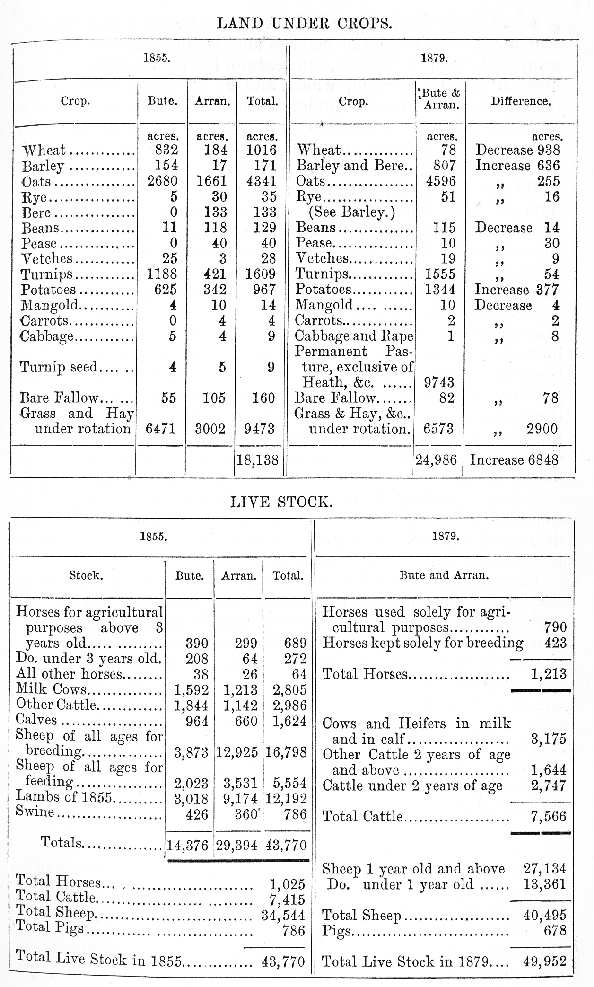

years, we here subjoin two tables of statistics compiled from reliable

resources. The first table shows the acreages of the various crops in

Bute and Arran in the year 1855, compared with the acreages of the same

crops as sown in 1879. The second table shows the numbers of live stock

kept in the islands in the former year, compared with the numbers kept

in the latter year. And we have no doubt that a slight study of these

tables will convince the reader that great progress in an agricultural

respect has been made by the county during that interval.

An analysis of the first of the foregoing tables will

show, 1st, a marked increase in the acreage under cultivation in 1879 as

compared with 1855; 2d, an extraordinary decrease in the breadth of land

growing wheat, and an equally extraordinary increase in the breadth

under barley; 3d, a decrease to the extent of 54 acres in the amount of

land under turnips, and an increase of 377 acres growing potatoes; and

4th, the acreage under sown grasses, sanfoin, and clover, shows a

decrease of 2 900 acres in 1879, but in the same column will be found an

item of 9743 acres under permanent pasture, not heath or mountain land,

against which there is no corresponding entry in the column for 1855.

The result of this analysis, therefore, is that there is found to be, in

1879, 6848 acres under cultivation more than there was in 1855 ; that

the growth of barley has in a great measure, though not altogether,

superseded the growth of wheat, that an increased number of acres are

now green cropped, and more potatoes are grown and less turnips than in

1855; and that there is a considerable increase in the acreage under

permanent pasture. As we proceed with our report evidence in support of

these statements will be furnished, and the causes which have produced

these changes will be referred to.

Coming now to the second table, we find that the

number of horses in the county has increased during the last twenty-four

or twenty-five years by 188 animals, the number of cattle by 151, the

number of sheep by 5951, while the number of pigs has decreased by 108.

The total increase in live stock over the period, therefore, is 6182

animals.

The only other statistical information, indicative of

the progress the county has made, agriculturally and otherwise, during

the period reported on, to which we will refer, is furnished by a

comparison of the rental of the county at intervals since 1855. In that

year, inclusive of the burgh of Rothesay, and the extensive

watering-place of Millport in Cumbrae, the entire valuation of the

county amounted to £53,567; in 1865, exclusive of Rothesay and

Millport, the valuation was £34,679; in 1870 it was £41,054; in 1875,

£43,725; and in 1880 it is £47,938. The rental of the island of Bute,

exclusive of the burgh, in 1880, is £25,109, 9s.; the valuation of

Arran, £20,136 10s.; and of Cumbrae, £15,690, 18s.

Bute.

The island of Bute, which gives the name to the

county, although not its most extensive division, is nevertheless the

richest in resources, and, taken as a whole, the most advanced in

agriculture. Its centre is in 55° 50' 1ST. lat. and 5° 4' W. long. It

lies 40 miles west from Glasgow, and 18 miles south-west of Greenock.

Its greatest length is about 14$ miles, its average breadth is about 3

miles, and its circumference about 35 miles. Including Inchmarnock,

which lies west of it about a mile and a half, its total area is

31,836.475 acres. Its highest summit is Kames Hill, which is 875 feet

above sea-level; and there are in it three lochs of some extent, viz.,

Loch Pad, 2¼ miles long by

¼ mile broad, Loch Ascog, and Quien Loch.

Naturally and geologically the island is divided into

four distinct sections. The Garrochhead, forming the extreme south, is

composed of steep rugged hills; trap rock protrudes itself on every

hand, and imparts to the scene, as viewed from the water, a very fierce

aspect. Proceeding north, the second division, lying between Rothesay

Bay and Kilchattan Bay on the one hand and Scalpsie Bay on the other, is

composed with slight exceptions of red sandstone. The third division,

extending from Scalpsie Bay to Ettrick Bay, consists of chlorite slate;

and the fourth division, from Ettrick Bay to the Kyles of Bute, is

composed almost entirely of micaceous schist. The mineral deposits of

the island are lime, coal, and slate, but all are of an inferior

quality.

The following description of the island, as one views

it from the steamer's deck when sailing round it, will give a general

idea of its fertility, and the measure of its agricultural enterprise.

Sailing from Rothesay northwards through the Kyles, before us lie

patches of cultivated soil beautifully laid out and lying well to the

sun, and alternating with these, little bits of moorland covered with

heather and whins. The land ascends gently almost from the water's edge,

and the further west one sails through the narrow strait between the

island and Argyllshire, the little cultivated plots on it become fewer

and fewer, till, at the point of the island facing Loch Bidden, it

presents one mass of almost barren rocks, on which grow a few patches of

scraggy wood. Indeed, the extreme north end of Bute may be said to be

almost uncultivated and unprofitable for cultivation.

Turning round the Buttock Point, the agriculturist

soon finds as he skirts the west side, that here farming is prosecuted

with energy, and that a somewhat cold and unkindly soil is made to yield

crops of fair average quality. In Ettrick Bay and Scalpsie Bay, and up

the straths which intersect the island from Ettrick Bay to Kames Bay,

and from Scalpsie Bay to Rothesay Bay, the soil is much more kindly, and

in the valleys patches of fertile loam relieve the monotony of sharp

sandy till which prevails throughout the island.

The south end, with the exception of the extreme

south, is well under cultivation, and Inchmarnock grows splendid barley

crops. Bounding the Garroch Head, Kilchattan Bay bursts upon the view,

with the beautifully wooded slopes of Mountstuart and Kingarth. In the

bay, and on the slopes and over the brows of the hills, the soil, which

is of a sharp gravelly nature, raises splendid potatoes

for the early markets. This eastern side of the island is much more

wooded than the western, and altogether presents a more pleasing

appearance.

The principal proprietor in Bute is The Most Noble

the Marquis of Bute, K.T. Mr Thomas Russell owns the estate of Ascog; a

portion of the island belongs to the burgh of Rothesay, and there are

also one or two other smaller proprietors. There are few parts of

Scotland in which the relationships of landlord and tenant are so

creditable and pleasant. Since the noble family of Stuart obtained

possession of the island in 1318, Bute has ever been a favourite

residence of the representatives of the house.

It was stated by the present bearer of the title,

when fourteen years of age, that his desire was that all his tenants

should sit easy, and in every instance when it has been necessary for

his desires to be consulted, the same spirit of anxious solicitude for

the good of his tenantry has shown itself. The widows of farmers who

have proved themselves unequal to the task of managing their husband's

businesses have been invariably pensioned, and it has been a rule of the

estate for many years that on expiry of leases no farms should be

advertised unless the tenant wishes to quit. All draining for the last

eighteen years has been executed at the landlord's expense, the tenant

paying 5 per cent. on his outlay. The steadings on the island are

commodious and in excellent repair, in which state they are maintained

by the landlord. Old tenants invariably have the first offer of farms to

let, and no farm is ever offered to the public unless the former tenant

is retiring from the business. On formally requesting it, permission is

given to all tenants to trap or snare rabbits on their holdings.

Besides treating their tenantry in this liberal

manner, the landowners in Bute have done much in the way of presenting

gifts to, and carrying out works of utility and interest in, the burgh

of Rothesay, to make that favourite watering-place even more popular

than it has been, and of course the greater the number of visitors to

Rothesay the brisker the demand for dairy produce. The Marquis has

renovated the old castle of Rothesay at great expense, and the

munificent gifts to the burgh of the late A. B. Stewart of Ascog Hall,

and of Thomas Russell of Ascog, should not be forgotten by those who

derive considerable benefit from the great influx of Glasgow visitors

during summer.

In addition to many other premiums a grant of £20 is

annually made to the funds of the Farmers' Society out of the exchequer

of the Bute estate office, and for several years, through the

instrumentality of the late Mr Henry Stuart, a silver cup was competed

for, which was eventually to become the property of the tenant on the

Bute estate who should twice be adjudicated to have the best managed

farm. This cup was awarded in 1867 to the late Mr Alexander Hunter, Mid

St Colmac; in 1868, to Mr James Duncan, Culivine; and in 1872 to Mr

Robert M'Allister, Mid Ascog, who, having again been awarded it in 1875,

now holds it in possession.

Burgh of Rothesay.

As the onward progress of industry in the island of

Bute is intimately connected with the wellbeing of the burgh of Rothesay,

a few particulars regarding the latter may not inaptly find a place

here.

Rothesay is situated on the east side of the island,

and has a population of well-nigh 8000 inhabitants. A considerable

amount of trade was until recently carried on in the town, and a

plentiful water-supply, suitable for use as a motive power, peculiarly

adapted it as a centre for carrying on the business of cotton-spinning.

One of the first cotton-spinning mills in Scotland was erected in 1780

on a site adjacent to the "lade" which runs from Loch Fad, nearly

opposite to the present Ladeside Mill. The incipient stages of this

industry were nothing very wonderful, but in course of time more

extensive works were erected, and the business was prosecuted for about

fifty years with tolerable success, until the dearth in cotton, caused

by the American civil war and several concurrent causes, brought about

the stoppage of the works, which have never been re-opened, and are

indeed now partially demolished.

The weaving trade was once represented in Rothesay by

three mills, but about eight years ago the Vennel Factory suspended

operations, and within the last two years the Broadcroft Factory has

followed its example, so that there is now only the Ladeside Mill

working. Various causes might be assigned for the cessation of this

industry, but the chief are perhaps the isolated position of the town

and the great improvements recently effected in the style of machinery,

against which less modern machinery is not able to compete.

The general adaptation of steam-power to shipping

dealt a severe blow to the timber shipbuilding trade, which was carried

on in Rothesay with great success for a long period of years. This

business latterly was represented by two firms engaged in separate

branches of the trade; the "Town Yard" dealing specially in those small

vessels of from 100 to 150 tons register, known as "Coasters," while the

"Ardbeg Yard" was chiefly employed in the building of fishing-smacks.

The failure of the west coast herring fishing during the past ten years

has, however, ruined this branch of the trade; and although the building

of the coaster class of vessels might have been persevered in, the

compulsory removal of the "Town Yard," some few years ago, to make room

for the esplanade, has extinguished that branch also.

But notwithstanding the collapse of these industries,

the prosperity of the town has not to any extent been impaired. Rothesay,

it is well known, is a favourite summer resort of the Glasgow folks;

large numbers of them flock to it yearly in quest of health and

recreation, and this has been a means of great advantage and prosperity

to the whole town and island. Many trades and interests have been

fostered and advanced by it, and amongst these, as may naturally be

supposed, the agricultural interest has come in for its due share of

advantage. As it is with this interest that we are chiefly concerned, we

will now proceed to remark more particularly upon it, making in the

first place some few observations on soil and climate.

Soil and Climate.

The characteristics of the soil in Bute vary greatly.

On the east side of the island it is of a sharp gravelly nature, and

rests on a substratum of red sandstone. Going north along the west side

of Port-Bannatyne or Kames Bay, the land lies very steep, and with the

exception of the fields along the shore, where the soil is deeper, and

the subsoil a gravelly clay or slate, the whole of the ground is thin,

and rests on a subsoil of red till. Passing through the valley from

Bannatyne Bay to Ettrick Bay, the soil is still gravelly, but is much

deeper, and large patches of loam are to be found. The deepest soil in

the island lies along the Bay of Ettrick, where there is a depth of

about 3 feet of earth, and a bed of gravel lying under. Fifty years ago

this was a huge marsh, and a bed of moss still runs along the greater

part of the farm of Mid St Colmac. In the valley of Glenmore, large

patches of deep moss and loam are scattered over the fields, and a

turnip crop has been grown in this year (1880), in this glen, which will

compare favourably with any in the island.

In the Commermenoch district, comprising the farms of

Larichorig, Baluachrach, Dunalunt, and Balichrach, the soil will be

found to be representative of all the different kinds of soil in the

island. The farm of Balichrach is admitted to be the most regular

crop-producing farm in the island, and on Ballycurrie, the soil is

light, free, and very easily wrought. In Kingarth, especially along the

valley from Scalpsie Bay to Kilchattan Bay, there is also great variety

of soil; on the higher grounds it is of a till and clay formation, and

therefore poor, but in the straths light sandy soil prevails, and an

occasional depth of good loam is met with.

Bute has been so long famed for its salubrious

climate that little need be said on the subject. Frost seldom continues

long, and is never very severe; and snow lies a very short time even in

the worst seasons. The salubrity of the island is so well known that

Rothesay has been called the "Montpelier of Scotland." There are two

very extensive hydropathic establishments, well-frequented—one at

Rothesay, and the other at Port-Bannatyne.

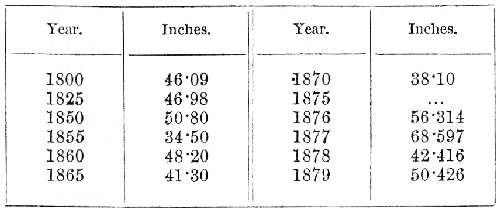

The following figures give the rainfall over a period

of years, as measured near Rothesay:—

Comparing these figures with the returns made for

other parts of Scotland, we find that in 1855 the average rainfall in

Bute was 34.50; in Dumfriesshire, it was 35.63; in Midlothian, 21.43; in

Strathearn, Perthshire, 19.20 inches. In 1870, Bute rainfall averaged

38.10; in 1876, 56.314; in 1877, 68,597; and in 1878, 42.416 inches;

whereas the gauge at Dunrobin Castle, in Sutherlandshire, gives the

following measurements for the same years, viz:—1870, 26.75; 1876,

34.62; 1877, 41.65; 1878, 34.36 inches. The results of this comparison

prove that the moisture of Bute is about the same as that of

Dumfriesshire, and that it is very much greater than the moisture of

Sutherlandshire. To take a particular point in each of the two

first-named counties, the rainfall in the town of Moffat measured, in

1855, 35.60, and the rainfall in Rothesay measured in the same year,

34.50 inches. These figures speak for themselves, and give a very good

idea of the general nature of the climate of Bute.

Retrospective Glance at the state of Agriculture prior

to 1850.

From a valuable "History of Bute" written by Mr John

Blain (who for sixty years previous to 1820 was intimately connected

with the island), and recently published by Mr Harvey, Rothesay, very

full particulars of the agriculture of Bute at the beginning of this

century can be obtained. It appears that about 1748 the Earl of Bute

introduced farmers from the mainland, in the expectation that the

natives would be induced to adopt their system of farming. The

introduction of these strangers did not, however, have such a beneficial

effect as was expected, and the landlord soon tried other experiments to

improve the condition of his tenantry. Nineteen years leases were

granted, and all rents were converted into money payments. In the low

state of farming pursued at that time many more cattle were kept than

the holdings would maintain, and the horses were of such inferior

quality that six of them were employed to draw the wooden plough then

used. Black cattle were general throughout the island, and were an

ill-conditioned bad-milking breed. It was one of the conditions of these

new leases that the stocks should be reduced, and for this purpose a

public fair was appointed to be held at Rothesay for the sale of the

surplus stock, of which fair the following extract from the "Glasgow

Journal," of 16th April 1765, is an advertisement:-—

"At Rothesay, in Bute, upon 28th May next, there will

be held a market of black cattle, sheep, and horses; the market, to

continue till all are sold off. As most of the tenants in the island are

obliged by their tacks to dispose of a third of their stock against

Whitsunday next, it is expected there will be a great, number of cattle

there.

"For the convenience of merchants, boats will attend

at Rothesay, and likewise at Scoulag Burn-foot, for carrying off

the-cattle sold, either to Largs, or anywhere up the river, freight

free."

While the Earl was thus

trying to improve the condition of the stocks by causing fewer animals

to be kept, he also offered: "a variety of premiums, such as, for the

best bulls, for the best dairy produce, for the greatest quantity of

butter and cheese produced by a given number of cows, for

well-compounded compost dung-hills, and a certain sum per acre for waste

land brought under cultivation." A Suffolk stallion was kept for

the,-use of the farmers' mares, and no fees were charged for his

service, and many other important improvements were promoted, by this

patriotic nobleman.

In 1805 or thereby his successor, following in his

footsteps, and actuated by the same laudable motives, sent, at his own

expense, half-a-dozen farmers' sons, bred on the island, to. be educated

by a Mr Walker, on the farm of Rutherford, near Kelso, and instructed in

the most approved systems of agriculture then pursued in Roxburghshire.

On their way east these young men passed through the country from

Glasgow to Edinburgh and from Edinburgh to Kelso on foot, and were thus

enabled to obtain a good general view of the whole agriculture of the

counties along their route. The curriculum through which these students

passed lasted for two years, at the end of which time they returned to

Bute, and were furnished with farms on the estate of the marquis at

reasonable rents. Their improved mode of farming, and intelligent

application of scientific principles, so far as then known, to the

cultivation of the soil, excited the interest of their neighbours, and a

generous spirit of rivalry was engendered, which tended to bring about a

remarkable change for the better in the condition both of the farmers

and of the land. As this fact seems to have been overlooked in all

former agricultural accounts of the island, no apology is necessary for

here inserting the names of several of the gentlemen who were the

principal agents in effecting this change. They included Mr James

Jamieson, who became tenant of Ambrismore; Mr Charles Stewart,

afterwards of Ardroscadale; Mr John Duncan, the tenant of Meikle

Kilchattan; Mr George M'Phee, North Inchmarnock; and Mr A. M'Intyre,

Dunalunt.

The next most important event in the early part of

this century, and one which has exercised an immense influence in

improving the agriculture of Bute, was the institution of the Bute

Farmers' Society. The idea of such an association was first mooted at a

meeting of the inhabitants of the island, held in the early part of the

year 1806, over which Mr John Blain presided, and at which he delivered

an address on the state of agriculture, which is given in extenso

at pages 274-283 of the history referred to,—an address remarkable alike

for its breadth of view, its fearless denunciation of abuses, and its

judicious recommendation of reforms.

The first object contemplated by the promoters of

this institution was discussion on agricultural topics, but in 1807, at

their March meeting, we find them making arrangements for holding a

ploughing-match, and settling the amount of premium to be offered

respectively for the best stallion and the best bull for breeding

purposes. At the first ploughing-match ever held in the island, that in

March 1806, premiums were offered by the Marquis of Bute, and twenty-six

two-horse ploughs competed, each being provided with a driver in

addition to the ploughman proper, but at the match held under the

auspices of the Society a year later, drivers were dispensed with, and

thirty-four ploughs appeared on the ground.

These ploughing-matches were in course of time

discontinued, it being considered that the object they had in view had

been attained, but premiums continued to be offered for the best fields

of turnips, the most successful crops of artificial grasses,

improvements in the breed of cattle, the best kept hedges, and the best

regulated farms.

At what time this budding society, which was

technically known as the Bute Agricultural Society, ceased to exist, it

is difficult to determine; its last published minute is dated the 16th

March 1807, but that it had been defunct for some time prior to 1820 is

clear from the fact that in 1821, Mr Samuel Girdwood, then in

Kerrylamont, proposed to revive the ploughing-match, and was empowered

by the farmers to collect subscriptions, and to call a general meeting

of the tenantry so soon as he had collected a sum sufficient to pay

adequate premiums to competitors. This scheme proved successful, and the

next development of the renewed agricultural enterprise took shape on

the 3d day of February 1825, when a meeting was held in Rothesay of

persons friendly to the institution of a Farmer's Society. The result of

this meeting was that the Society which still exists was founded, having

for its object the promotion of agricultural improvement in all its

branches, to be attained by the granting of premiums, the formation of a

library, and the holding of meetings for discussions on agricultural

topics. This Society has done very much towards the furtherance of

agriculture. By the premiums offered for dairy cows of pure breeding and

good milking qualities it has fostered dairy-farming, till it is now

almost in as flourishing a condition as could be desired. By the

introduction of good Clydesdale stallions it has enhanced the value of

the draught horses, and by its premiums for the best fields of turnips,

&c, it has greatly increased the profitableness of green-cropping in the

island.

Modern Farming.

As Lord Bute may be said to have been the principal

agent in abolishing the last remnants of primitive farming, and Mr John

Blain may be said to have been the forerunner of scientific farming, so

the honour of being the inaugurator of the modern era in Bute farming

must be awarded to Mr Samuel Girdwood. This gentleman about forty years

ago held the offices of steward to Lord Bute and secretary of the

Farmers' Society, and was also tenant of the farm of Kerrylamont in

Kingarth. He was a man of more than average intelligence, of great force

of character, and possessed of unbounded enthusiasm in the furtherance

of a favourite pursuit. His tombstone in Rothesay churchyard tells us,

that he was for forty years connected with the estate of the Marquis of

Bute; "distinguished by fidelity in his trust, ability, skill, and

success in the discharge of his duties, and zeal for the public

interest." Under his fostering care the Society progressed wonderfully,

and by the introduction of furrow drains and the system of liming, the

reclamation of waste lands was vigorously prosecuted. Through his

instrumentality, a lime-kiln was established at Kilchattan Bay, and the

limestone found in the island was there burned and utilized, and a

premium was offered by Lord Bute for the best heap of composite manure,

i.e., of farmyard manure, mixed with such waste as the sweepings

of the farmyard, and the "scouring" of the roadside drains, &c. On the

farm of Kerrylamont he carried on various experiments, the results of

which, when successful, were communicated to the farmers. In order to

facilitate interchange of opinions by practical men on agricultural

questions, Mr Girdwood, in conjunction with Mr Alexander Anderson, the

first letterpress printer in Rothesay, issued, on the 26th November

1839, the first number of the "Bute Record of Rural Affairs," a

publication which continued to be issued regularly until January 1846,

and which in its republished form (1860) furnishes an excellent

reference work to the student of agricultural progress in Bute.

Having thus brought the review of the agriculture of

Bute prior to the period on which we are asked to report to a close, we

now proceed to give somewhat in detail particulars of farming operations

during the past twenty-five or thirty years.

The system of farming differs little if at all from

that commonly pursued in the west of Scotland. The rotation of crops at,

and some time previous to the commencement of the period reported on,

was what is known as a seven years' shift, i.e., the ground lay

three years in pasture, and four under crop, but for the last twenty

years or more a six years' shift was substituted; in all the new leases,

however, the seven years' shift has again been reverted to. The land

lies under pasture for three years ; it is then broken up by the plough,

and the fourth year an oat crop is sown; the fifth year it is green

cropped; the sixth year it is sown down with oats or barley and

rye-grass and clover seed; and the seventh year a crop of rye-grass and

clover is taken off. No two white crops are allowed to be taken off in

succession without the consent of the landlord.

Taking these crops in the order of their rotation we

are first called upon to give a few particulars of the

Oat Crop.

The established custom for the last fiftyyears has

been to import for seed purposes Midlothian "potato" and "sandy" oats

from the Edinburgh markets. On the higher lands, where the ground is

shallow, and of a heavy clayey nature, "sandy" oats are invariably sown,

and on the deeper and more fertile lands scarcely any but "potato" oats

are produced. "Hamilton" oats are found to grow admirably on the light

soils of Kilchattan Bay, and weigh about 42 lbs. per bushel. The land is

broken out of grass during January and February, and sowing is begun in

April, and thought to be completed in good time when the seed is all in

by the 20th of that month. In the north-east of Bute damage is often

done to the growing crop during the month of June by gales of east wind,

which shake the grain when in flower, and although the bulk of straw is

often very great, the result of thrashing is many times disappointing.

The crops are generally first harvested in North Bute,—not that the soil

there is capable of raising earlier crops than the soil in Kingarth, but

the farmers on the east side of the island give all their attention in

the early part of spring to the potato crop, whereas generally

throughout the rest of the island the farmers give equal attention to

white and green crops. The reaping-machine is now, and has been for many

years, in use on almost every farm in Bute, and very few acres are now

cut with the scythe or hook, and these only when the crop has been much

flattened by the storms. The first who introduced a successful

reaping-machine was Mr John M'Dougall, the tenant of Kerrytonlia who

purchased one of Jack's reapers about twenty or twenty-five years ago. A

very few acres may occasionally be let to Irish reapers

by the acre but this mode of harvesting

is now nearly obsolete. The hands necessary for the management of the

farm during the year are usually equal to the extra demands of harvest

time, but if additional workers are necessary they can easily be

procured in Rothesay.

The average produce of oats per acre in 1855 was 32

bushels, and the average of fiars prices for the seven years ending

1856. was 23s. 6|d.; the average produce per acre in 1880 will be about

the same as in 1855, and the average of fiars prices for seven years

ending 1876 was 24s. 6 11/12d. per imperial

quarter. Over a period of years the bushel of oats will weigh on an

average about 40 lbs. and when ground a 6 bushel bag of oats usually

yields 140 lbs. of meal. The habits of the people of Bute have greatly

changed during the past twelve or fifteen years, and whilst formerly a

large proportion of grain was ground into oatmeal, now only a very small

proportion of it is devoted to this use.

Green-Cropping—Potatoes and Turnips.

The early history of green-cropping in Bute is

interesting and instructive. As we have seen, the chief proprietor early

gave tangible proof of his interest in the improvement of agriculture,

and the Highland and Agricultural Society, as well as the local Farmers'

Society, later on, did something to encourage the growth of green-crops.

The National Society, in 1851 and 1852, and in several following years,

offered premiums for the best managed green crop in the island, and in

1868 a premium was offered by the agent for the best 2 acres of turnips

and potatoes grown with Goulding's manures. The Highland

Society's medals fell to the lot of the tenant of Mid Ascog in

1851, 1852, 1854, and 1855, and the premium offered by Goulding was also

awarded to him. Prizes of a like nature were awarded on different

occasions by other donors, and the competitions for them did much to

make the farmers bestow increased care on these important crops.

For many years Bute has been known as one of the

earliest places in the west of Scotland for the growth of potatoes.

These favourite roots grow well on the sharp gravelly soil of Kilchattan

Bay and Kingarth, and the farmers in that district vie with each other

in sending the earliest potatoes to the Glasgow market. In the spring

time potatoes used to become rather a scarce commodity in Bute, but the

advent of the "Champion" potato has somewhat obviated the danger of a

local famine of these vegetables. "Bed Bogs" is the principal variety

planted for sale in the early markets. The average price of early

potatoes is about £18 per acre; although in Kilchattan Bay from £20 to

£24 have been obtained in an exceptionally good season. The buyer digs

the crop, and the farmer drives to the place of shipment free of charge.

On some of the shore farms the stubble is during winter covered with

seaweed, but in general it is ploughed down or grubbed about Martinmas,

and again ploughed in February. Potatoes for early sale are planted as

soon as possible after the end of February. The width of potato drill is

from 25 to 26 inches, the latter figure being the standard. The crop is

in most cases sold to dealers from Glasgow, and the frequent

communication between Bute and the mainland—steamers sailing hourly

during summer, —admits of the crop being lifted and transported to

Glasgow in a very short time.

In the extreme northern portions of the island and in

the more exposed situations, potatoes are only grown in quantity

sufficient to supply the wants of the family. On one of the farms in

Kingarth, in 1880, a fair crop of barley has been raised on a field on

which a crop of early potatoes was grown. The potatoes were lifted about

the middle of June, and the barley was sown on the 26th and 30th of the

same month. This is rather an unusual proceeding (rape-seed being

generally sown on the potato ground), and its success will be watched

with interest.

Turnips.

The growing of these favourite feeding-roots forms a

large part of the agriculture of Bute. Turnips were first introduced

into Bute by Mr Knox, then tenant of Kerrylamont, in 1800.

The sorts now in most common use are purple

top Swedish and green top yellow, and

about one-half of the breadth under turnip crops is sown with the

former, and the other half with the latter variety. As a rule the whole

produce of the crop is consumed by the stocks on the farms, but a good

exportation trade is carried on by some of the farmers. The turnips are

shipped in bulk, and sold in Glasgow and Greenock.

The average width of turnip drill is 27 inches. In

the south end of Bute the turnip crop has—since the growing of early

potatoes assumed its present important position—been chiefly grown with

artificial manures, as the farmyard clung is all required for the

earlier crop. In North Bute and Commermenoch, where less attention is

given to the early potatoes, an effort is made to sow the crop on manure

formed of an equal proportion of byre and stable manure and artificial

stuffs. Generally it may be said that the farmers are now using more

ground bones than formerly, and within the last few years it has become

necessary to use a good deal more town manure, and on one farm in

Kingarth, in the winter of 1879, upwards of 400 tons have been spread.

For the storage of the turnip crop during winter

different plans are adopted. On the eastern side of the island the

produce of two drills is gathered into one furrow, and covered over by

the plough. On the western side the turnips are only taken out of the

ground as they are needed, the earth being put up to them at the

beginning of the winter. The system, so successfully carried out in

Dumfriesshire, of feeding sheep on the growing crop, has been tried in

Bute, but on account of the moistness of the climate it was found very

unprofitable, and the practice has been discontinued.

The average yield of turnips per acre in 1855 was 15

tons 11 cwts; the average yield of Swedish turnips in 1870, about 18

tons; and of yellow, 14 tons. For thinning turnips the services of

female workers can be secured at about 2s. per day, and of male workers

at about 2s. 6d. per day; in both cases without food.

Summing up the report on green-cropping, it must be

said that the most unprofitable branch of farming during the last ten

years has been the growing of early potatoes, and those farmers who have

bestowed more attention on the turnip crop are to-day better off than

the others, and their farms are in much better condition. Turnips leave

the soil in much better condition for the growth of the next crop, and

one can easily distinguish by the appearance of the white crop whether

it has been sown on potato or on turnip ground.

Barley.

Up to within a recent period wheat was extensively

grown in Bute. About the time of the Crimean War white wheat was grown,

and was the most successful and most profitable crop raised in the

island. Seasons were then very favourable, prices were high, and on one

of the most northerly farms the average of 48 bushels per acre was

realised on a field of 10 acres. Barley, however, has for the last

twenty years more or less been increasingly cultivated, and, as a

result, has now almost entirely supplanted wheat. The reason for this

change of crop has chiefly been this: the ready market which is found

for barley in the distilling districts

of Campbeltown and Islay, and the increasing foreign supplies of wheat,

which have rendered it more profitable to grow barley. The change of

crop has also proved beneficial in another way: it has tended to the

good of the soil, because barley keeps the ground much cleaner, and does

not take so much of the strength out of it as wheat.

The red land alone is sown with barley; indeed, it

may be said that, with the exception of the moorland farms, all the

sown-down land is cropped with it. The variety sown is in general that

known as common barley, although in the north end, and wherever the land

is strong and in good condition, the farmers prefer the "Chevalier"

sort, as it is the more profitable.

Experience has taught the farmers in Bute that

home-grown barley is ill-adapted for seed purposes, and consequently all

the seed is brought from Midlothian. The heads of the home-grown seed

become black, and the yield is not up to what might be expected. The

Midlothian grain usually weighs about 56 lbs. per bushel, and the

average weight per bushel of the barley crop is from 52 to 54 lbs.

Barley harvest in a fairly good season begins about the 15th of August,

and the crop in the south end is commonly hutted in the fields, and

thrashed off the huts by the large thrashing mills, two of which travel

the island in circuit. In the north end the crop is stacked in long

stacks placed four abreast, and containing about twenty cartloads

a-piece. The mill stands between the two inner stacks, and the tops

being taken off these, the sheaves from the outer stacks are forked on

to them, and from them on to the machine. The outer stacks being thus

disposed of, the sheaves of the inner are then passed through the mill.

The barley straw on being thrashed is stored in long square stacks, and

is used during winter in various ways. Some of it is cut into chaff,

steamed, and mixed with meal and turnips for feeding purposes; the rest

of it is used for "litter," and a little of it for thatch.

Rye-grass.

When land in Bute was newly reclaimed great

quantities of rye-grass seed were ripened and sold for exportation. At

that time the ripening of rye-grass seed was one of the features of Bute

farming. Sometimes the yield per acre has been known to be as high as 6

quarters. In 1853 the Highland and Agricultural Society's medal awarded

for the best sample of perennial rye-grass seed grown in Scotland, was

gained by Mr James Duncan, Rhubodach; and in 1854 the same medal was

gained by Mr John Stewart, Baluachrach, in Commermenoch district. The

average yield per acre will not now be more than 2 quarters; the great

majority of the farmers cut their hay green and winnow it, and the

ripening of it is only permitted on such farms as are best suited for

the process, when the crop is exceptionally clean. The weight per bushel

of this season's (1880) rye-grass seed averages from 23 lbs. to 28 lbs.,

and the price realised for it is from 1s. to 1s. 3d. less per boll of 4

bushels than the price of that sampled in Ayrshire.

Eye-grass seed is invariably mixed with clover, and

the second growth of clover in a season such as 1880 could hardly be

matched in any part of Scotland. On Mid Ascog and Colmac this season

(1880) there has been a crop of great bulk, which has been winnowed and

stored for fodder.

Cattle and Dairy-farming.

The native breed of cattle in Bute, which were

presumably of Highland origin, although many of them were polled, have

long-been superseded by the Ayrshires. Dairy-farming is one of the

principal departments of the rural economy of the island, and as the

demand for dairy produce increased, so it became the interest of the

farmers to meet it by improving their herds, and increasing the milking

qualities of their cows. We are able with tolerable certainty to

establish the date when the first Ayrshires were introduced. The

earliest occasion on which a prize was specially awarded at the annual

show for Ayrshire cows was in 1830, but the breed had been in the island

fully a quarter of a century before that date. Among the first, if not

the very first, to introduce Ayrshires, was Mr Thomas Stevenson, who in

1803 came from Neilston, in Renfrewshire; to the farm of Edinmore, and

brought with him a number of Ayrshire calves, which were brought over by

ferry from Largs to Scoulag, and were then travelled across the island

to the west side, near Colmac. Mr William Barr also came from Ayrshire

about the same time, and brought with him a small stock of the breed of

his native county. These gentlemen were followed soon after by Mr

Johnstone, the father of the present tenant of West St Colmac, who came

from West Kilbride, Ayrshire, in 1809, and by Mr Robert Hunter, Mid St

Colmac, also an Ayrshire man, both of whom brought herds of pure bred

Ayrshires with them. The cattle brought in by these strangers must have

soon commended themselves to the natives, because we find that the

Stewarts of Balichrach and Baluachrach, who are said to be a family

resident in Bute for about three hundred years, have long had excellent

herds of Ayrshire cows. The herd presently on the farm of Baluachrach or

Upper Ardroscadale, was founded by the late Mr Robert Stewart in May

1833, from purchases made in the island. A bull was bought from the late

Rev. Alexander M'Bride, minister of the parish, and afterwards of the

Free Church, North Bute, which greatly improved the breed, and sires

have been introduced from the mainland which have maintained its

superiority. Mr Stewart was awarded the first prize, twenty years ago,

for the best aged cow in milk, and also a silver medal as owner of the

best six cows shown.

In 1856 a selection of Ayrshire cows was made from

herds in Bute, and sent over to the Paris Exhibition as the joint

adventure of several farmers. The cows were all sold at a good profit,

and one selected from the herd of M.id Ascog, was awarded the bronze

medal as one of the best cows in milk in the exhibition.

The Mid

Ascog herd was founded aboutl850,withcowspurchased in the island,

and its superior milking qualities were maintained by the use of bulls

from the herd of Mr Murdoch, Carntyne, near Glasgow. Up to about 1870

only bulls from this herd were bought in, and during that period many of

the leading prizes at the local show were awarded to Mr M'Allister, the

tenant of Mid Ascog. From 1859 to 1880 scarcely a year has passed

without his gaining medals for his Ayshires, and the trophies won by him

can hardly be enumerated. After the Carntyne herd was dispersed bulls

were purchased from the Burnhouses breed, and by the exercise of great

care in mating sires and dams the excellency of the herd has been

maintained.

The herd of Mid St Colmac, owned by the late Mr

Alexander Hunter, and formed from stock brought from Ayrshire by him,

was one which for many years upheld the credit of Bute dairy cows in

show yards all over Scotland. After the death

of Mr Robert Hunter the farm was carried on and the stock greatly

improved by his son, and at his death a few years ago it was sold by

public auction, and the prices realised were the highest ever obtained

at a displenishing sale in Bute. The three-year-old queys drew very high

prices, and three of them sold respectively at £33, £28, and £25

a-piece.

Several of the highest priced animals were purchased

by the present tenant of the farm, and with the herd founded by his

father, Mr James Simpson, on Largivrechtan about thirty-four years ago,

they now form the magnificent herd of forty dairy cows on Mid St Colmac.

The Largivrechtan herd was founded from purchases made in Ayrshire, and

from cows purchased from Mr Lochhead, 'Toward, Argyllshire; the bulls

have almost invariably been purchased from the tenant of Boydston,

Ardrossan. One of these bulls was the sire of twenty prize animals, and

several high priced cows have at times been added to the herd, including

the famous cow "Joan," bred at Knockdon, and sold at the Auchendennan

sale of Ayrshires some few years ago.

The Bute herd, however, which has come most to the

front, in shows on the mainland in recent years is that of Meikle

Kilchattan. This herd was founded fourteen years ago from purchases made

in the island. Bulls have been used bred by Mr Scott, Plane Barm, Bute;

Mr Ivie Campbell, Dalgig, New Cumnock; Mr Fleming, Castleton, Carmunnock;

Mr Brown, Cartleburn, Kilwinning; and Mr Howie, Burnhouses. These were

all good breeding sires, but the Cartleburn bull effected the greatest

improvement in the breed.

As these dairies touched upon, are, with Balichrach,

the most extensive in the island, the details of the way in which their

quality has been maintained may serve as an indication of the general

method of breeding Ayrshires followed in Bute.

Queys are seldom or never bought in, but bulls almost invariably are.

The quey calves are all kept to keep up the herds, but the bull calves,

unless very promising, are sold as unfed veal to the butchers. As a rule

the aged cows are not kept after they are ten years of age unless they

have proved themselves to be extra valuable as breeders. Cows which

calve in autumn sell at about £15 per head; those calving in spring draw

from £12 to £14.

The produce of the Bute dairies is either sold as

sweet milk or manufactured into fresh butter, for both of which there is

an abundant demand in Rothesay, Port-Bannatyne, and Ascog. A good deal

of fresh butter is also sent out of the island. A boat crosses from

Kilchattan Bay to Millport with supplies of butter, and quantities are

also sent to Dunoon. When the dairy trade began at first to develop

itself in 1810, the milk was all sold skimmed; after a time a demand

arose for mixed "skim" and. "sweet" milk, and again butter milk was in

favour; but for many years sweet milk has been exclusively in demand.

Cheese was somewhat extensively manufactured in former times. The writer

of the " Statistical Account," in 1840, tells us that the "cheese then

made was equal to the best Dunlop," but this remark does not now hold

good. Bowing establishments are-very rare; the farmers generally sell

the produce of their dairies without the intervention of any middle

party, as by this means they receive about 2d. a pound more for their

butter than they would by selling it wholesale to merchants in Rothesay.

The first farmers who sold milk from carts in the streets of Rothesay,

were Mr John Currie, then in Ardbeg, and Mr Thomas Stevenson, Ardmalish.

Fresh butter sells out of Rothesay at about 1s. 5d. per lb. on an

average, and fresh country eggs, sent from Bute at about 1s. per dozen.

In Rothesay the consumer can purchase butter produced by the Bute

dairies at about 3d. a lb. less than he-would pay in Dunoon or

Helensburgh, as the supply in the island exceeds the demand.

The price of sweet milk, wholesale, is about 4d. per

imperial pint; of fresh butter, wholesale, about 1s. 2d. per lb.,

retail, 1s. 4d. to 1s. 6d.

As there is not a market for all the butter milk

churned in the island, for the last twenty years it has been usual for

many of the farmers to make the sour milk into a curd for dye, which is

sold to merchants in Glasgow. The milk after churning is put into a

large vat, and a slow fire being put under, it is allowed to remain

there for two days; at the end of that time,

being now formed into a curd, it is taken out and put into a suspended

bag, by which means the whey is allowed to drip out of it. It is

afterwards taken clown, and put under a cheese-press for a time, and is

then sent off to the Glasgow market. The price received for the curd is

from 18s. to 20s. per cwt. which is about equal to three farthings a

pint, or within a fraction of the price usually obtained for butter

milk. The sour milk whey is mixed with meal, and forms excellent food

for the pigs.

Sheep.

Sheep-farming is not very extensively followed in

Bute. All the farms carrying pure bred stocks are in the north end, and

the chief of them are Rhubodach, Kilmichael, Hilton, and Glenmore. The

stocks carried on these hills are mixed flocks of blackfaced ewes and

wethers. A little more than thirty years ago several of the farmers sold

off their blackfaced sheep and bought in Cheviots, but it was found that

the Border favourites were very unprofitable, and for the last twenty

years there have been few or none of them in the island. An experiment

was also tried on one of these farms with crossing blackfaced ewes with

Leicester tups, but on account of the difficulty experienced in keeping

up a blackfaced stock the experiment was abandoned. Thirty years ago the

sheep on the Bute hills were very small and ill-conditioned, but,

chiefly through the energy of Messrs Crawford and Duncan, the tenants of

Kilmichael and Rhubodach, by the selection of good tups from the

mainland, a great improvement has been effected in their quality. The

tups in use are for the most part bought in from the flocks of Craigton,

Milngavie, Foyer's, Knowehead; and Jardine's, Campsie.

The tups are generally let out with the ewes about

the 20th November, and the lambing season extends from the middle of

April to the middle of May. After going with their dams between three

and four months the lambs are weaned, and about the middle of August all

the tups and stock lambs are dipped with the usual compositions. The

lambs are kept from their dams for about eight days, at the end of which

time they are sent off to the hills again, and usually find their old

quarters. At weaning time the weakest of the lambs are sold off to

graziers, who winter them and sell them in the ensuing autumn as hoggs,

to make up the stocks on farms where cross-bred lambs are reared.

The "cast" ewes are drawn about the 1st of October,

and clipping begins about the same date. For dipping, a trough is in

use

into which two sheep can be put at once, and by this means the work is

got over very expeditiously. Smearing has now been almost universally

abandoned, because of the amount of extra time and labour it involves;

though occasionally black-faced ewes are smeared with a mixture of tar

and butter, in the proportion of 1 gallon of tar to 6 lbs. of butter—a

quantity sufficient to smear six sheep. The clip after smearing with

this composition generally yields about 6 lbs. of wool per fleece.

Clipping begins about the middle of June, and is continued till the end

of the month; the milk ewes are about a fortnight later of being clipped

than the others. Taking an average over ewes and wethers, the produce of

the clip will give about five fleeces to the stone of 24 lbs. Wethers in

some cases will occasionally give a clip of 8 lbs. of wool.

The average rent paid for purely sheep farms is about £18 per every 100

sheep carried. The prices realised for shot lambs range from 6s. to 8s.

per head; for draft ewes, from 16s. to 18s. each; and for wethers, about

31s. per head.

On several of the arable farms which have also a

piece of moorland included in them, another branch of sheep-farming is.

carried on. The tenants of these farms buy in at the beginning; of

winter a number of cross-bred or half-bred hoggs, which they winter on

grass, with the addition of a few turnips and a little corn, and sell

again in summer to the butchers. Some sell before clipping, others after

having taken off the fleece. These hoggs are bought in at prices ranging

from 20s. to 30s. a-head, and are sold after the six or seven months'

keep, at prices averaging from 40s. to 50s. each. These hoggs,

unclipped, now sell at about 1s. per lb., clipped hoggs, at about 8d. or

9d.

A few Cheviot ewes are kept on one or two farms, and

are-crossed with Leicester tups, for the supply of cross-bred lambs for

the butchers. The lambs are sold about the middle of June,, and draw

about 30s. a-piece. The ewes, when the lambs are taken off them, are fed

off, and, if fat, draw about 5s. a-head more than the price for which

they were purchased. Sometimes the difference between the buying and

selling prices of these ewes is even greater than 5s., and when the

value of their clip is taken into account, it is apparent that this

system of sheep-farming is by no means unprofitable, and many farmers

think it should be more generally adopted. It has now been pursued for

the last twenty or thirty years on two or three farms. One of the

tenants keeps Cheviot ewes in stock, shoots out the slack ewes, and buys

in hoggs to maintain the stock; the others sell off the ewes and; buy in

a new lot every season. Sheep are brought in now from Argyllshire in

October, to be wintered for six months at 6s. 6s.. a-head. Whether this

is profitable or not for the land it puts money into the farmers'

pockets for the time being.

Pigs.

In the table at the commencement of this paper we

have given the relative numbers of pigs in Bute in 1855 and in 1879, and

it only remains further to be added here, that these animals are only

kept to the extent of one or two on each farm, for the purpose of

consuming the waste about the kitchen, and that pork-feeding forms no

part of the rural economy of the island.

Horses.

During the last quarter of a century there has been

little change in the quality of the horses bred in Bute. For some time

prior to the period reported on, and during it, the farmers have been

fortunate in securing some of the best Clydesdale stallions ever known

in Scotland to travel their island. The Sproulston horse "Farmer"

(Stud-book, 290) was the first to effect a marked improvement in the

quality of the stock, and after him "Round Robin" (721), "General

Williams " (326), and "Young Clyde " (1360), greatly increased the value

of the young horses reared in the island. In more recent years

"Surprise" (845), "Young Lorne" (997), and others, have been secured by

the Farmers' Society to travel under their auspices. "Druid" (1120), the

well-known champion horse of 1879 and 1880, also was engaged by the Bute

farmers, when a three-year-old, in 1878. The best horses are undoubtedly

to be found on the west side, on the deep land of Ettrick Bay, but the

east side has also come to the front through the reputation of the

famous mare "Rose of Bute" (89). Horse-dealers visit the island

regularly, and buy up any of the stock which may not be required for

home purposes. Generally the mares are not of the largest size, and

there is an apparent lack of the finely flowing fringe of hair on the

legs, so much accounted of by Clydesdale fanciers. Clydesdale mares were

introduced into Bute by Mr James Simpson about forty years ago, but

whether these were the first pure bred importations we have not been

able to ascertain. It must be between thirty and forty years since

"Farmer" (290) travelled the island, and "Round Robin" (721) was there

in 1854 and 1855. About this latter date Mr Robert M'Allister, Mid Ascog,

held a leading place in the local show with his mares, and bought in one

from the stud of Mr Robert Findlay, Springhill, Baillieston, which bred

many excellent animals. At the time when Mr Simpson came from Ayrshire,

and "Farmer" (290) was traveling, the native breed must have been

somewhat inferior, and in all probability of Highland origin, because

the very first year Mr Smpson was

in Bute he gained the prize as the owner of the best

pair of mares at the ploughing match. It is questionable if very

heavy mares could be raised in Bute; the soil is not so

well adapted for grazing purposes, and the pasturage is very bare

compared with that of the fertile lands of Galloway and Kintyre, and,

therefore, so long as the needs of the island are best served by a horse

somewhat light of limb, the present breed may be considered the best for

all purposes. The farmers find a ready market for their surplus stock,

and mares from Bute have been sent all over Britain, and even to the

colonies. With the produce of such horses as "Druid" (1120) and "General

Neil" (1143) coming up, there should be little danger of the stock being

deteriorated.

Draining and Liming.

The first draining operations of any extent carried

on in Bute were commenced more than fifty years ago by Mr Kirkman Finlay,

who at that time was proprietor of the lands of St Colmac. The farm of

West St Colmac was the first that was drained in Bute on the Deanston

principle, and all the deep land on the level fields around Ettrick Bay

were reclaimed from a state of unprofitableness. A drain plough was

introduced by Mr Finlay, but it proved unworkable on account of the

number of boulders buried in the marshes. There is double the extent of

arable land in Colmac now that there was forty or fifty years ago, and

what was then considered good arable land has been very much improved by

lime and draining.

When Mr Samuel Girdwood began reclamation works on

the Bute estate he encountered much opposition from the indifference of

the farmers in seconding his efforts to improve the soil. He broke

ground on the farms of Cranslagvourarty and Largivrechtan, but the

tenants of those days were not able to see the force of all his

blasting, digging, and draining labours. In their hands the dry patches

on the hillsides were cultivated, but where-ever nature asserted her

supremacy by the presence of whins and marshes, no efforts were made to

battle against her. Whins, rocks, and brushwood were left to the freedom

of their own will, and stagnant bogs remained untouched. Mr Girdwood

succeeded in convincing the tenants that it was for their advantage to

clear the land, and the result in the case of one of them at least was,

that when he went out of the farm he went with something very like a

fortune.

About thirty years ago it was customary for the

proprietor to pay the tenant who broke new land a premium of £5 per

acre, but he gave him no lime. On the farm of Kerrycroy, in Kingarth,

upwards of 20 acres of waste land have been reclaimed during the past

twenty or twenty-five years, and all the steep land lying along the

hillside on the farm of Kilbride, in North Bute, has been

reclaimed within the same period. About ten years

previous to that time 40 or 50 acres were taken in on the farm of Mid

Ascog, and margins of moorland have throughout the island been

reclaimed. Previous to the last eighteen years, when the land was much

drained, farmers received half value in lime for the expense of draining

done by them, but since that time they only receive half value for lime

used in reclamation, and all drains are made by the landlord, the

tenants paying 5 per cent. interest on the outlay. Much of the soil that

has been drained is so thin, that in many cases the interest payable

increases the rent so much that farming is made unprofitable both to

landlord and tenant. There are tile works situated in the parish of

Kingarth, from which drain-tiles can easily be obtained, and a

lime-kiln, which many years ago was in operation, has again commenced

burning the limestone found in the island. The farmers in the south end

prefer Bute lime because it does not require shipping, but those in the

north end find they are as cheap to use Irish lime, as in either case

shipping has to be resorted to, and the quality of the Irish shells is

much superior.

Ploughing and Manure.

The common single furrow plough is that most in use

in Bute. The plough is in most cases drawn by two horses. Subsoil

ploughing is seldom practised, but in general throughout the island

there is no subsoil to plough. Stubble land is ploughed shortly before

and after Martinmas; pasture land is broken about the beginning of

January; and red land is turned over as near the time for barley sowing

as possible.

Iron harrows are mostly, if not altogether, in use in

the island, and chain harrows are also common. Grubbers and drill

harrows of the usual kinds are generally in requisition, and some

farmers grub the stubble land at Martinmas with the three-horse grubber

instead of ploughing it.

Artificial manures have been greatly in use in Bute

both for raising potatoes and turnips, but especially the former.

Peruvian guano, ground bones, and within recent years "Blood" manure

have been put into the soil, and the fact is, too many artificial stuffs

have been employed, and now many of the farmers are importing large

quantities of town manure from Greenock. Upwards of 800 tons of long and

short town dung were put on farms in Kingarth in the winter of 1879, and

this kind of manure is gradually supplanting the other. On land where

much artificial manure has been used lime has not the same effect as it

had when the land was reclaimed, and in many cases liming in recent

years has not been remunerative. Long dung can be purchased in Greenock

and laid on the fields in Bute for about 7s. per ton ; short dung or

ashes for about 3s. per ton. If purchased in Rothesay long dung can be

laid on the fields for 6s. a ton, and the police manure is given to the

farmers for taking it away.

Pasturage.

The pasturage of Bute enjoys no great reputation, and

purely pastoral farms are very scarce. Within recent years the tenant of

Rhubodach, Kilmichael, and Bannatyne Mains, has maintained the last

named farm as a grazing farm by top dressing with short dung and

farmyard manure, mixed with lime and ground bones. Ayrshires, Highland

bullocks, shorthorns, Galloways, and Canadian cattle are grazed on this

farm, and fattened for the markets. The only other grazing of any extent

is around the Mount Stuart policies, and it is let to farmers and others

for grazing young stock.

Wages.

As in the rest of Scotland so in Bute the cost of

working a farm has almost doubled, in respect of wages, within the last

twenty years, and were it not that, with machinery in use for almost

every purpose, fewer hands are required, it is difficult to conceive how

farming could be carried on, rents also having increased so much until

recently. Married ploughmen in Bute at present are receiving 18s. per

week with a free house. Female servants, good milkers and field workers,

boarded in the house, are paid from £8, 10s.

to £9, and lads receive from £8 to £12, with board, per half-year; About

twenty-five years ago the same class of women servants were receiving

about £3, 10s., and lads about £5 per

half-year with board and lodgings. Female field-workers employed

thinning turnips in 1880 were paid 2s. a-day without rations, and the

same workers in harvest time received 2s. a day with rations. Men

employed during harvest time received from 6d. to 1s. a-day more than

the women, with their rations, and full wages whether the weather was

wet or dry. The wages of these workers in 1880 were just about double

what they were in the years from 1855 to 1860.

GREATER CUMBRAE.

Having thus exhausted our information regarding the

agriculture of Bute, a few particulars of the island of Cumbrae may best

be inserted here before proceeding to write of the agriculture of Arran.

Cumbrae has everything in common with Bute, but little or nothing in

common with Arran. The island lies 4 miles east of Bute, and 2 miles

west of Largs, in Ayrshire. It is 3½ miles in

length from north-east to south-west; its breadth is 2 miles, and its

circumference from 10 to 11 miles. According to the measurement of the

last Ordnance Survey it contains 3120.597 acres.

The climate is agreeable, being less moist than the

mainland or Arran, and very salubrious. The geological formations are

whinstone, freestone, and limestone. The soil is varied; on the higher

parts of the island it is light, gravelly and thin, bedded on moss, and

covered with heath; in some of the valleys rich loam pervades, and

produces good crops. Along the east coast it is light and sandy, and in

the south of the island it abounds in marl.

The island is owned by the Marquis of Bute and the

Earl of Glasgow. All the old part of Millport is built on Lord Bute's

estate, which extends from Newton Bay across by Barbary Hill to Fintry

Bay, and includes all the land between this line and the west coast; the

rest of the island belongs to Lord Glasgow.

Along the north end of the island, on the farm of

Port Boy,, great improvements have been effected within recent years by

draining and liming. Good crops are raised on the new land, and wheat is

very extensively grown. Early potatoes are cultivated with somewhat

similar energy as in the east of Bute. Cumbrae potatoes, however, are

about a fortnight later of being ready than those in the earliest parts

of the sister island. On the top of the second terrace which rises on

the west side there is some very deep land, and good crops of turnips

are raised on it. Lime has not been very largely introduced into Cumbrae,

but great quantities of sea-weed are spread on the fields.

All the farms on the island carry stocks of dairy

cows numbering from 20 to 40. The milk is for the most part sold as

sweet milk in Millport, where there is a brisk demand for it during

summer. A few of the dairy-farmers churn, but not regularly, and one

sends his milk to Glasgow.

The stocks on the farms are in good condition; there

is only one sheep-farm in Cumbrae, and it carries a blackfaced stock of

average quality. The horses are much the same as in Bute, and Ayrshire

cows alone are kept for the dairies.

The burgh of Millport, situated at the south end of

the island, is one of the best frequented watering-places on the Clyde.

The influx of visitors during summer is very large, and communication

between Glasgow and Millport is kept up six times a day by the steamers

in connection with the Wemyss Bay Railway Company's trains.

The assessable rental of Millport in 1865, the year

following that in which it was created a

burgh, was £5,451; in 1870 it was £7,519; in 1872 it

was £8,710; in 1875 it was £10,581; in 1877 it was £11,401;

in 1880, it is £12,998. In fifteen years, it will

be seen from these figures, it has more than doubled its rental,

and there is every prospect of its progressing as rapidly in future.

Leaving now the beautiful islands of Bute and Cumbrae, it only remains

for us to add that, with the maintenance of the same cordial

relationship between landlords and tenants, which has so long obtained,

and the fostering of that spirit of enterprise which has actuated the

labours of the farmers during the past twenty-five years, still further

improvements may be made, and we have every confidence will be made, in

agriculture and all other industries.

Arran.

The island of Arran lies about 8 miles south-west of

Bute. It is about 20 miles long from north to south, and about 10 miles

broad. It is divided into two parishes—Kilbride forming the eastern

section of the island, and Kilmory the western. The northern part of it

is crowded with lofty granitic mountains of & conical form,

connected by sharp, serrated ridges, and intersected by deep gulleys and

ravines. The highest point in the island is Goatfell, which is 2,900

feet high. The southern part of the island, which is geologically

divided from the northern by a band of Old Red Sandstone, crossing the

island from behind the village of Brodick, is formed of undulating hilly

ground, sloping gently to the sea. The whole, with the exception of the

small estate of Kilmichael, belongs to His Grace the Duke of Hamilton

and Brandon, who, according to the "Parliamentary Return of Owners of

Land in Scotland," furnished to the House of Commons in 1873, holds

102,210 acres in the county of Bute, the gross annual value of which

then was £18,702. The Kilmichael estate consists, according to the same

authority, of 3,632 acres, the value of which was £622.

The climate upon the whole is mild and moderate. Snow

never lies very long; the heat in summer is not long very intense, and

neither is the cold in winter. Rain falls copiously, and the prevailing

winds are south and west. The soil varies greatly; one field may

sometimes be found which contains patches of stiff clay, soft moss, and

loam or gravel, or both mixed together. In many places along the shore,

especially in the north end of the island, it is little else than

granitic sand washed down from the mountains and driven back by the sea.

In the more fertile regions loam is in most cases mixed with gravel, and

interspersed with patches of moss. In Whiting Bay the soil is chiefly

sharp the shingle resting on a subsoil of red till. The best land is in

Southend and Shiskan on the west side of the island. The road to Lagg

leads over the hills from Lamlash, and the road to Shiskan leads over

the hills further north from Brodick.

The Holy Isle, lying in the entrance to Lamlash Bay,

grazes a few sheep and goats, and the small patch of arable land at the

north end of the island is now wrought on a regular rotation of crops.

Pladda, lying a short distance off the Kildonan shore on the south end,

is cultivated by the lighthouse keepers, and grows the usual garden and

field seeds.

General Review of the Agriculture of Arran.

To report on the state of agriculture in Arran during

the past thirty or forty years is a matter of considerable difficulty.

There has been progress made, and there has been stagnation. The larger

farmers have done much to improve their holdings, some of the smaller

farmers have done a little, but many of them

have done nothing. Little or no encouragement

to improve land is given by the superior; game is preserved to an

inordinate extent, and the smaller tenantry, especially in "Whiting Bay

and Lochranza districts, combine the occupations of fishermen and

farmers, and depend more on the letting of their houses to summer

visitors than on the produce of the soil. When Dr M'Naughton wrote his

"Statistical Account of the Parish of Kilbride," in 1840, he says: "In

dairy-farming and the art of cultivation the smaller farmers have yet

much to learn. They put little lime on their lands, neglect the cleaning