By Donald Stalker, Forester, Kilmun.

[Premium-—Minor Gold Medal.]

Benmore and Kilmun estates, of which James Duncan,

Esq., is proprietor, are contiguously situated in the united parishes of

Dunoon and Kilmun, in the Cowal district and southern border of

Argyllshire, and for a considerable distance run along the Firth of Clyde.

The total area of Benmore and Kilmun estates is 12,260

acres, extending from the Firth of Clyde to the north end of Loch Eck,

while on the south it possesses the advantage of having partially for its

frontier the River Eachaig, whose source is in Loch Eck, and, after

meandering through and fertilising an extensive plain, falls into Holy

Loch, to which and Loch Long, an opposite inlet from the Clyde, the estate

has a frontage of five miles.

About four miles in extent, running along the Holy Loch

and Loch Long, has been feued and closely built upon with superior

sea-coast summer residences; while immediately behind these there is a

sloping belt of full-grown larch, oak, and birch trees, which impart

ornament and afford shelter to the houses below. Behind this lies the

arable and grazing laud, which has a gradual ascent to the base of a wide

curving range of hills, and terminating at an elevation of 1800 feet.

The northern boundary of the estate, extending along

and rising abruptly above the western margin of Loch Eck for a distance of

seven miles, is a continuous chain of hills, the highest being Benmore,

about 2500 feet high, and anciently known as the Deer Forest of Argyll.

The soil consists chiefly of light sandy and gravelly

loam, lying on slate rock, alternating with narrow veins of quartz,— the

prevailing substratum throughout the entire estate. On the surface

abundant evidence is given of the excellence of the green pasture, and but

for the presence of brackens, which abound in many parts, suppressing the

grass, the soil is otherwise admirably adapted for grass.

Benmore House is situated near the south end of Loch

Eck, and head of the extensive, undulating, and fertile valley of Eachaig,

the greater part of which until recently was in a wild state of nature,

overgrown with brushwood, heather, and rushes. On it Mr. Duncan now grazes

his celebrated West Highland cattle and blackfaced sheep, which acquired

such celebrity at the Paris International Exhibition in 1878, and continue

to carry off the first awards at the annual exhibitions of

the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland.

In 1870, when the proprietor obtained possession of the

estate, he resolved on effecting extensive improvements; but preparatory

to commencing operations, arrangements of a most amicable nature were

entered into with a few of the tenants to give up such portions of their

hill pasture as Mr. Duncan considered should be planted.

With three of the largest grazing farms on the estate

in his own hands, Mr. Duncan was enabled, both by tile-draining and

ploughing, to bring under cultivation all waste lands adapted for that

purpose; while on moorish wastes and portions unreclaimable he planted.

And in testimony of the extreme suitability of both soil and climate for

growing wood, the following statements may be narrated. About sixty-five

years ago, on the base of the hill immediately behind Benmore House, where

previously only a surface herbage of coarse grass, brackens, and heather

existed, 55 acres or thereby were planted with larch, Scotch fir, Norway

spruce, and several species of hardwood, chiefly with the view of

contributing to the amenity and shelter of the house,—the present average

value of which per acre is £70, and, since planted, it has yielded an

annual rent of over 25s. an acre.

Thinnings have from time to time been cut during the

last ten years for estate purposes, the money value of which would not be

less than £500; and although it is impossible now to ascertain the actual

value of the thinnings antecedent to 1870, it may reasonably be assumed

they would have been sufficient to defray the outlay of capital on

formation. The trees are with few exceptions healthy, and where the soil

and subsoil are of a sandy, gravelly, and porous nature, still growing

vigorously; but in some parts at the top of the enclosure, where the

surface soil is mossy, retentive, and resting on rock, the larch trees are

very diminutive, having scarcely made any growth for years, and some are

disfigured with wounds known as "larch blister," and gradually decaying,

giving evidence to the fact that the planting of larch trees on exposed

rocky ridges, meagrely covered with inferior soil (indeed, in all adverse

soils and situations), is the chief cause of the many diseases to which

that very valuable tree is subject. The ground on which these trees now

stand was, before being planted, almost valueless for grazing purposes,

but so transformed has it now become as to be yearly worth 10s. an acre,

and on it are grazed nearly all the year round a number of young Highland

cattle; thus showing the profit and advantage of planting ground otherwise

lying waste, over and above what was necessary for ornament and shelter.

With such conclusive proof of the advantages to be

gained from planting such portions of the estate as under heather and

brackens were of no value whatever, and considering that many of the best

trees forming the plantation already referred to might at any time be

uprooted by violent winds, and the amenity of the house suffer thereby,

arrangements were made by Mr. Duncan for planting extensively such steep

and rocky portions of his estates as could not be reclaimed and brought

under cultivation.

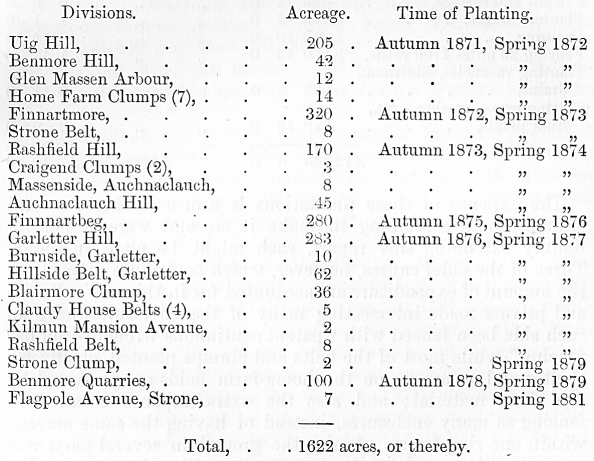

Since 1871 thirty-one separate enclosures have been

planted, the extent of which amounts to about 1622 acres, and the number

of trees to 6,488,000. The following indicates the divisions and acreage

of each and time of planting:—

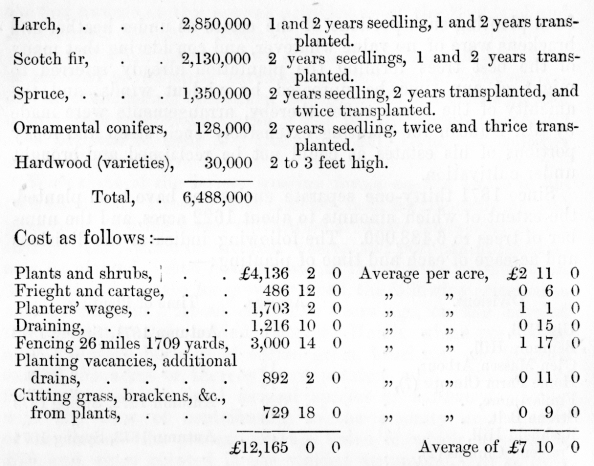

As there has been a succession of foresters on the

estate since planting operations were first commenced in 1871, neither the

number of plants nor their value can be exactly ascertained, and the

difficulty of forming a correct estimate is further increased by the fact

that large numbers of plants were transplanted from "Benmore home

nurseries" from time to time without any correct account having been kept,

but the following is a near approximation to the species, age, and cost of

plants, as also the amount of capital expended on the formation of the

plantations including fencing, draining, planting, &c.:—

The expense of these plantations is unusually high,

several circumstances combining to make it so, and were it not for unduly

extending this report, each might be cited in detail. Three of the chief

causes, however, which contribute in swelling the amount of expenditure

are accounted for in this way: Public and private roads intersecting many

of the enclosures, have on each side been fenced with "patent continuous

wrought-iron bar fencing," while most of the belts and clumps planted,

chiefly for shelter and ornament, on the home-farm fields are protected by

the same material; and also the extra expense entailed in fencing so many

enclosures, instead of having the same acreage within one ring fence.

Again, the ground in several parts was covered with a rank surface

vegetation of brackens, grass, &c, so hostile to the growth of young

plants, that strong large-sized plants had to be used; while on exposed,

wet,. and retentive portions close planting and extensive drainage had to

be resorted to.

A description of the soils, species of plants,

altitudes, and fencing, mode of draining and planting, will now be given.

Uig and Rashfield plantations are situated to the east of the river valley

of Eachaig, opposite Benmore House, with a north-western exposure, and at

an average height of about 450 feet. The ground is steep, undulating, and

rocky. The surface soil, consisting of sandy peat, is on the ridges and

tops of precipitous rocks coated with heather, while the intervening

hollows are of an open, sandy, and gravelly nature, and covered with

brackens and grass.

The substratum consists of clay-slate and quartz rock

alternating, and prevailing throughout the entire estate, with but a few

narrow seams of whinstone. Turning attention again to Uig and Rashfield

plantations, on the ridges of which native Highland Scotch pine, Pinus

Laricio, P. austriaca, and P. montana, with a mixture of

mountain ash, have been planted, and into hollows, or wherever the

adaptation of the soil was favourable, larch was planted, interspersed at

distances of from 15 to 30 feet apart, with several varieties of

coniferous and deciduous trees, including P inus insignis, P. excelsa,

P. austriaca, P. Laricio, and P. Strobus, Picea Nordmanniana, P.

pectinata (common silver fir), P. balsamea, and P. nobilis,

Abies Douglasii and A. Menziesii, Cedrus Deodara, Purple beech,

and scarlet oaks. While higher up the hill, Norway spruce and Scotch firs,

were mixed with the larches, and in places where brackens and grass fought

for mastery, black Italian poplars and sycamores.

The Dunoon and Kilmun public road to Inveraray, via

Loch Eck, partly intersects, and for a distance of two miles skirts

the base of these plantations. Along the road, on both sides, are grouped

together ornamental conifers, including Wellingtonia gigantea,

Araucaria imbricata, Cedrus Deodara, C. atlantica, Picea Nordmanniana, P.

nobilis, P. pectinata,, P. lasiocarpa, P. Pinsapo, Abies Douglasii, A.

Menziesii, A. Albertiana, A. Englc-manii, A. nigra,, A. alba, and

A. Smithiana, Pinus Laricio, P. Benthamiana, P. exeelsa, P. austriaca,

and P. cembra, Thuja Lobbii, Thujopsis borealis, Cryptomcria japonica

(the Japan cedar), C. elegans (the elegant cryptomeria), and

Cupressus Law-soniana, the number of plants in each group varying from

five to a hundred, according to the extent of the various nooks and

recesses between the rocks, which are crowned with native highland Scotch

and other hardy pines. Larch, Scotch fir, and Norway spruce have been

planted in all the groups, to shelter the tender plants.

These trees have also been planted into groups by

themselves on marginal parts of the plantations, partly for ornament and

also to test their adaptation for becoming profitable timber trees in this

country, and for the latter purpose they have been placed well back off

the boundary fences, and at intervals of about 12 feet apart. The borders

of the plantations near to public and private roads are, immediately

behind the fencing, lined with deciduous trees, evergreen and flowering

shrubs, comprising purple beech, walnuts, purple and variegated planes,

scarlet oak, common hawthorns, single and double flowering scarlet

hawthorns, common and golden laburnums, lilacs, bay and Portugal laurels,

common and variegated hollies, Rhododendron ponticum, Mahonia

aquifolium, cotoneasters, and other ornamental trees and shrubs.

Great care has been bestowed on these plantations.

Additional drains have been made, and all blanks planted up; and what was

some nine years ago the most bleak and uninteresting hillside is, now that

the young trees are developing with vigour and uniformity, most imposing

and picturesque. Another improvement has been effected on this part of the

estate, and one which contributes in no small measure to its attractions.

A bridle path, five feet wide and nearly two miles in length, has been

lately constructed, at a cost of 2s. per lineal yard, including rustic

wooden bridges which span the burns. The path diverges from the public

road opposite "Loch Eck porter's lodge," and curves up through the

plantation and across the face of precipitous rocks with an easy gradient,

till it reaches the south side of it, at an altitude of 600 feet. At this

point it connects itself with a road one mile in length, and quite

recently formed along the course of Uig burn.

Entering the glen at the top of Uig and Rashfleld

plantations, we follow the course of the burn which divides these, and

although our eyes can no longer feast on distant scenery, fresh beauties

and grandeur are here disclosed to view. Between huge overhanging rocks,

in the crevices and sides of which are an endless variety of ferns,

mosses, and other Alpine plants, the burn flows rapidly down in a series

of waterfalls ; and the road which leads into the nurseries is shaded over

its entire length with oak, elm, alder, birch, mountain ash, and hazelwood.

Wel-lingtonia gigantea, Picea Nordmanniana, and many other

ornamental conifers, have been planted into recesses in the rocks in this

glen, which for wildness and grandeur is by few equalled, and certainly by

none excelled in the west coast of Argyllshire.

In the home-farm fields the trees planted in clumps are

making rapid progress. The soil is various, consisting of hard gravel,

other parts of sand, and along the margins of the river and throughout the

largest portion of the farm the soil is moss, mixed with a fair proportion

of sand.

As already stated, the fields in Eachaig valley have

but very recently been reclaimed, and a most interesting illustration of

the good effects of cultivation is here shown in the contrast between the

luxuriant crops of corn, ryegrass, and turnips, which surround the clumps;

while round the young trees, which stand from 6 to 10 feet high, there is

a covering of rank heather nearly 2 feet in height.

Finnartmore and Finnartbeg plantations are contiguously

situated on an eminence confronting the Holy Loch and Firth of Clyde at an

average height of 550 feet. The ground is steep, yet comparatively regular

and smooth on the surface. The soil, which is covered with grass,

brackens, and heather, seems admirably adapted for the growth of timber,

being a rich gravelly loam resting on a subsoil of gravel and rocky

debris, and being naturally dry, comparatively few drains were required.

From the base upwards, two-thirds of the grounds have

been planted chiefly with larch; while the higher slopes and summits are

planted with native highland Scotch pine.

Evergreen and ornamental conifers, including 8000

Picea Nordmanniana, and clusters of mostly all the hardier species of

the silver fir, pine, spruce, cypress, and cedar, have been interspersed

among the larch, at distances varying from 15 to 30 feet apart, so as to

give some verdure during the winter months, and also to have a variety of

profitable timber trees growing on the ground after the larch trees are

removed. Norway spruce has been planted almost exclusively on patches

growing a strong vegetation of grass, brackens, and rushes; while on rocky

parts, thinly covered with mossy soil, native highland Scotch pine was

planted. As in the case of Uig and Rashfield, these plantations have been

carefully gone over a second time, and attention bestowed on wet and blank

spots. The trees are all healthy, and making rapid progress. The larch,

Abies Douglasii, A. Albertiana, Thuja Lobbii, Pinus Laricio and P.

insignis, which grow apace in congenial soils and favourable

situations, have now reached a height of from 10 to 12 feet. The other

pine trees, although not so high, are growing rapidly, and appear in

perfect health. Previous to being planted, the ground presented a bleak,

sterile, and uninteresting appearance, but now that it is almost clothed

from base to summit (highest elevation about 1200 feet) with young trees,

it is a pleasing object in the landscape along the Holy Loch and Firth of

Clyde.

Garletter plantations are so named by reason of their

being in the glen of same name. The exposure is easterly, at an average

height of nearly 600 feet. The largest division is situated on the eastern

extremity of Kilmun estate. The surface-soil consists of decomposed sandy

peat, resting in turns on rock and yellowish gravel, and mostly covered

with grass. From the wet and retentive nature of the ground, close and

extensive draining had to be resorted to, yet it withholds the needful

sustenance from the young trees, especially on high and exposed parts.

After a time, however, when the plants attain such dimensions as to cover

the ground, and thereby suppress the strong grassy vegetation, they may be

expected to grow as well as trees in the more favourably situated

plantations. In kindly soils, which contain a larger proportion of gravel

and sand, and consequently are drier, the larch, Norway spruce, and Scotch

firs are growing satisfactorily.

Auchnaclauch plantations in Glen Massen have a

northwestern exposure, and an average height of 250 feet, and in respect

to both ground and plants they are very much similar to Uig and Rashfield.

Glen Massen arbour plantation is within the Benmore

policies, with a north-western exposure, and an average height of 150

feet. The trees are very thriving, and making rapid progress, particularly

the larch, Abies Douglasii, Picea Nordmanniana, and Scotch firs.

Benmore hill and Benmore quarries plantations are

situated side by side on the hill immediately behind Benmore House, with a

south-eastern exposure, and an average height of 450 feet. The ground and

general state of these plantations is very much similar to Uig, but

differs in this respect, that Benmore quarries plantation is not so far

advanced, having only been in existence for three years, and also that it

contains more Abies Douglasii than the others. Forty thousand of

these were planted as an experiment, and in congenial soils and sheltered

situations have made magnificent progress; but on exposed sites they have,

with few exceptions, been deprived of their tender tops by the frosty

winds.

Craigend, Strone, and Blairmore belts and clumps were

primarily designed for shelter and embellishment, and were placed at

judicious intervals on the grazing fields, in close proximity to the

summer residences along the sea-shore. All the trees give evidence of

health by their rapid growth.

Fencing.—Uig and Rashfield plantations are, on each

side of the public road, protected by "continuous wrought iron flat bar

fencing," which cost from 2s. 9d. to 3s. 6d. per lineal yard, according to

the state of the iron market at the time the fences were erected. Uig

plantation, on the northern extremity of Kilmun estate, has a march fence

constructed solely of iron, 3½ feet above ground, with seven wires (of No.

5 and No. 6 best bright wire) laced between the standards, with No. 8 wire

fastened to top and bottom wires; wrought iron standards, 1¼ inches broad

by | inch thick, batted into stones placed 7 feet apart, with iron

side-stays 5/8 inch square at every fifth standard in curving parts of the

fence; one wrought iron straining pillar, 1½ inches square at 100 yards or

thereby, which make it a most substantial fence, scarcely ever out of

repair, and therefore most suitable for the boundary of an estate. The

cost was 1s. 6d. per yard. On the upper and side boundaries there is a

six-wire fence (of No. 4 and No. 5 best bright wire) stapled to larch

posts 5½ feet long, pointed and driven into the ground at 5 feet apart,

with a larch stay at every alternate post. This fence, which cost 9d. per

yard, is a most servicable one, and by the time many of the posts require

replacing, thinnings from the plantation will be of a sufficient size for

the purpose.

Rashfield, on the upper and side boundaries, is

enclosed with a six-wire fence (of No. 5 and No. 6 best bright wire) 3

feet 4 inches high; iron standards, 1¼ inches broad by ¼ inch

thick, batted into stones placed 6 feet apart; iron straining pillars 1½

inches square. The cost per yard was 1s. 5d., and it is a most durable and

sufficient fence.

Finnartmore and Finnartbeg are in part protected by a

wire fence 3 feet 4 inches high, and by a rough stone dike 4 feet high, on

the top of which is a double line of wooden rails nailed to larch posts,

and reclining against the dike on the inside. The fence is a six-wire one

(of No. 4 and No. 5 best bright wire), with iron straining posts on the

summit, and larch ones along the base and west side of the enclosures. The

cost was about 8½d. per yard.

Benmore hill and Quarries plantations are surrounded by

a common six-wire fence, larch posts and straining posts, and in part by

the Corriemony fence. Auchnaclauch plantations have been enclosed with

iron and wire fencing, similar in every respect to that of Rashfield.

Garletter plantations are enclosed with "Corriemony

fencing," 3 feet 3 inches high above ground, with angle iron standards

batted into stones at 22 yards apart, with six steel wires of Nos. 8

and 9, stapled to larch droppers at 6 feet apart; iron straining

pillars at intervals of 200 yards, with an iron stay to every standard.

The cost was 7d. per yard, but soon proved itself unable to withstand the

wintry storms, which levelled considerable portions of it on the most

exposed sites; and, although intermediate standards were at once put in,

placing them at 11 yards apart, yet it is still insufficient and

constantly requiring repair, which, owing to the brittleness of the

material, is difficult to do. All these fences, in the present state of

the iron market, could now be constructed cheaper.

Draining.—The ground was drained by contract, and

also by men employed at a fixed rate of wages per day. The method adopted

in draining the steep and rocky enclosures was, by having all the wet

ground drained by "surface drainers," who, with "big spades" and other

tools adapted for that purpose, performed the work far more expeditiously

and at less than a fourth of the price than could possibly be the case by

using the ordinary spades or shovels. The drains were made from 2 feet to

2 feet 3 inches wide at top, 18 inches deep, and 6 to 8 inches broad at

bottom, in places where the soil admitted that depth. The cost of making

was from 1s. 9d. to 2s. 6d. per 100 yards, according to the soil. All

parts which required deepening were subsequently gone over a second time

by day labourers, and sunk with pick and shovel a sufficient depth into

the subsoil.

In deep loamy and mossy soils open drains were formed

by contract, and also by day labourers. The dimensions of the drains were

from 2½ to 3 feet broad at top, 2 to 2 feet 9 inches deep, and 6 to 9

inches broad at bottom, according to the soil. The cost was from 9s. to

12s. 6d. per 100 yards. All the soil taken out in forming the drains was

spread over the surface of the ground.

Planting.—Planting operations were performed under

the constant supervision of the forester and an assistant.

The plan devised for transporting the plants to their

new habitation was carried out in the following way. But first of all, and

in nursery phraseology, the plants were properly "shouched" into dry

ground at the base of and within the enclosures. Four Shetland ponies, on

whose backs pack-saddles were strapped, and into which the bundles of

plants were placed (roots inward), proceeded on their march up the hill in

pairs, each being tied to the other's tail, and under the charge of a man

and boy. On reaching their destination, the plants were again "shouched"

close to where the planters were at work. Pits were formed for deciduous

broad-leaved plants, and also for ornamental and expensive pines, which

were interspersed amongst the others in suitable soils at moderate

altitudes, and at distances varying from 12 to 30 feet apart.

The usual number of men in one squad, notching the

plants into the ground with common garden spades, was about a dozen, and

two lads were fully employed in keeping up the supply of plants to the

hands of the boys and girls, each of whom inserted them into the slits or

notches made by every two men. The plants were placed at from 3 to 3½ feet

apart, or an average of 4000 to the acre.

The situations and boundaries of the plantations were

carefully laid off, with the view of providing shelter for the flocks on

the adjoining grazings, and to promote this object the fencings were

carried along in curving lines, thereby forming a series of spacious

recesses, into which the flocks might congregate in snowstorms and

inclement weather during the lambing season.

There are upon the estate about 100 acres of what may

be called fully grown larch and pine timber, and upwards of 300 acres

under old hardwood and deciduous trees; and Mr. Duncan has from time to

time expended large sums in improving the latter. The brushwood,

smaller-sized and inferior coppice wood trees are being gradually thinned

out, the woods drained, and replanted with conifers, rhododendrons, and

other underwood shrubs. Woodlands, to the extent of about 50 acres, have

already undergone this improvement, and for this purpose, and the planting

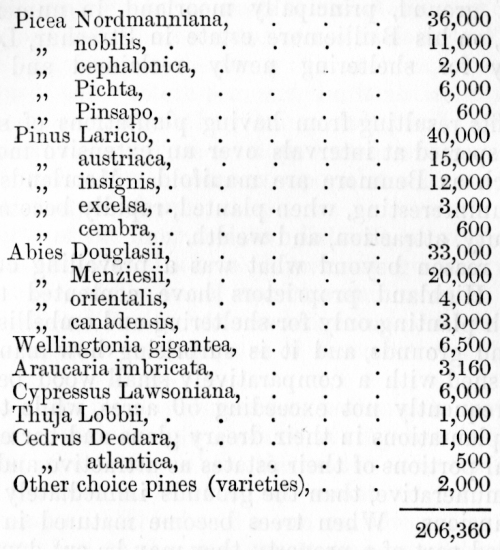

of other portions of the estate, there are growing in Benmore

home-nurseries the following conifer and ornamental trees:—

The nursery also contains a collection of hardwood

plants, besides an extensive stock of true native Highland Scotch fir.

The situation of Benmore House is a most desirable one.

The gardens, greenhouses, and fernery are of themselves sufficient to

attract the admiration of visitors to the locality. But another and still

greater treat has been provided for them. It consists of a picture gallery

erected in 1879-80, and is situated in close proximity to the house. In

length it is 150 feet, by 60 feet broad, and 40 feet high. The walls are

adorned with most interesting and valuable works of art, many of them

being extra large-sized paintings by some of the most eminent ancient and

modern masters; while the centre of the gallery is filled with statuary,

embowered with crotons, palms, ferns, and other graceful foliage plants.

That the public evince a due appreciation of this

splendid acquisition to Benmore House is evident from the fact that

hundreds of people are availing themselves of the liberty at all times

granted of inspecting the gallery.

The policies are extensive and exceedingly interesting,

being intersected by two rapidly flowing rivers, Eachaig and Massen, in

both of which salmon abound. About four acres of ground, stretching along

the sides of Loch Eck Avenue and Echaig riverside, have been formed into a

pinetum, and three acres along the banks of the Massen are being gradually

converted into an arboretum by the introduction of duplicate and single

specimens of all the hardy trees known in Britain.

Mr. Duncan has also planted within the last six years

about 30 acres of ground, principally moorland, in numerous belts and

clumps, on his Bailliemore estate in Strachur, Loch Fyne-side, chiefly for

sheltering newly reclaimed and improved parks.

The benefits resulting from having plantations of

serviceable timber interspersed at intervals over an extensive mountainous

property such as Benmore are manifold. Moorlands the most sterile and

uninteresting, when planted, rapidly become a source of great beauty,

attraction, and wealth.

From no reason beyond what was a prevailing custom, the

majority of Highland proprietors have contented themselves hitherto with

planting only for sheltering and embellishing their mansions and grounds,

and it is surprising how many of them are still satisfied with a

comparatively small wood behind their dwellings, frequently not exceeding

50 acres, while they might by forming plantations in their dreary glens

and barren hillsides make several portions of their estates as attractive

and, certainly far more remunerative, than the grounds immediately

surrounding their mansions. When trees become matured in a glen or other

secluded part of a property, they may be cut down without in any way

detracting from the general aspect of the estate. Several extensive landed

proprietors at the present time being well aware of the advantages to be

derived from the planting of moorlands, have placed large tracts of their

properties under forest trees, and none of them will ever have occasion to

regret this, as it increases their revenues and greatly improves the soil

for pasturing purposes, as well as the climate.