By Robert Hutchison of Carlowrie.

[Premium—The Gold Medal]

We have no planted oak, ash, elm, or fir, of so old a

date (about 1500), as the country was then full of natural woods composed

of those trees, and very little demand for them."

Sir Thomas Dick Lauder, who considered the sycamore to

be an indigenous tree, notices the predilection for planting it in

Scotland, when he says it is "a favourite tree," and "if the doubt of its

being a native of Britain be true, which we cannot, however, believe, then

it is probable that the long intimacy which subsisted between France and

Scotland may be the cause of its being so prevalent in the latter

country." With this cause of the origin for the sycamore being so

extensively planted in Scotland we are fully inclined to agree, and an

additional collateral reason for this assumption is found in the many

individual specimens of the sycamore which tradition points to as having

been planted by the hapless Mary Queen of Scots, and which to this day are

called "Queen Mary's Trees." Several of these, still extant, will be found

noticed in the tables appended to this report, and they occur at places

where the unfortunate Queen either resided when in Scotland on her return

from France, or around the scenes of her dreary imprisonments. Many other

fine old relics of these troublous times are still to be found by Border

keep and feudal tower, flourishing in vigour by the crumbling ruined

fortalice, or in the spot where the baronial garden had once existed,

while several of the largest and most noble specimens still linger, and in

some instances continue to maintain a green old age, by the ruined

monastery and cloister wall. Planted in such sites, evidently with care,

and for some special reason—it might be on account of its rarity at the

time, or for its hospitable shady foliage—there seems little room for

doubt that the sycamore was first introduced from the Continent about the

time we have indicated ; and for the earliest examples still surviving we

must look to such localities as we have described and recorded, in the

tabulated appendix to this report.

Another reason for the general diffusion of this tree,

after its introduction over the various counties and districts of

Scotland, is to be found in the peculiar capacity which its twiggy habits

of young wood and growth presents, of withstanding with impunity the

severe blasts of wind which are so prevalent in many parts of Scotland,

and also its singular suitability for resisting the sea breeze in insular

or sea coast localities. Numerous instances of its successful introduction

and growth in such situations are recorded in the appendix. Indeed, no

better examples could be found than those of the many specimens we have

noticed from the sea coast of East Lothian and Berwickshire, where large

and handsome trees may be seen situated quite within the influence of the

sea breezes and easterly gales that sweep across the North Sea, and yet

quite unaffected either in vigour or in contour by

such inclement influences. We find it also planted for

shelter and shade round many a hill side and exposed hamlet and steading

at high altitudes; and, although at great elevations the sycamore does not

attain to the ponderous dimensions it acquires at the lower levels, it

still grows to a considerable girth and height of hole even in these

higher positions. Thus, for instance, at Woodhouselee, Mid-Lothian,

altitude 700 feet (vide Return), we find it thriving and

vigorous in light gravelly loam, on a gravelly and rocky subsoil, and

about 60 feet high, and girthing over 16 feet at 1 foot from the ground,

and 13 feet 4 inches at 5 feet; while at other high elevations, such as at

Dalwick, Peeblesshire, 800 feet; at Stobo, 745 feet; at Lochwood,

Dumfriesshire, 900 feet; at Ardross, Rosshire, 800 feet. Similar and in

some cases even larger dimensions are attained by the sycamore {vide

Table). In regard to soil, this tree is not fastidious; it will be

found from our returns to thrive well in any soil which is not overcharged

with moisture. In such situations early decay of the trunk and oozing from

the stem near the base are produced; but, while preferring an open good

loam, rather dry, it is also found thriving in stiff soil inclining to

clay. Its progress is most rapid in deep dry soft loam, and in such

circumstances it is no uncommon thing to find the sycamore, in Scotland,

planted out singly in open situations, attaining 20 feet in height in ten

years; and Grigor states he has known instances of its having attained the

height of 40 feet in less than twenty years. At Twizel, in Berwickshire,

in a light dry loam, the sycamore in twenty-five years attained the height

of 35 feet in an exposed situation, and had a diameter of stem near the

base of 12 inches.

The sycamore is one of the earliest of our forest trees

to put on its foliage in spring. The tints of the opening buds and young

tender leaves "are rich, glowing, and harmonious," as Sir T. D. Lauder, in

his edition of "Gilpin's Forest Scenery," well describes them. They deepen

in summer into darker green, contrasting well with the massive

wide-spreading head of the tree, and in autumn the varied browns and reds

with which they tartan the woods harmonise well with the lighter yellow

shades of the declining foliage of the lime and elm and ash in the

landscape. In old trees, the habit of peeling off in scales, which

is noticeable in their bark, produces an agreeable effect in the rich

contrast between the ashy-grey colour of the adhering bark, and the russet

hues thereby produced and displayed in patches along the trunk.

Considerable variety and difference of time also, in foliation, is

observable in the sycamore in this country. In this respect one tree,

still extant and quite vigorous, near the ruins of Corstorphine Castle,

and adjoining the old dovecot of that barony, has acquired a unique

reputation, and given its name to a new family or variety of the sycamore.

This tree puts forth its buds and young foliage ten days or a fortnight

earlier than any other sycamore, of which there are many in the immediate

vicinity. Its young foliage—which is very dense, from the compact, close,

round-headed habit of the tree, and which has caused Sir Walter Scott to

remark appropriately of the "Corstorphine Plane," that it "has no

weather side" although exposed in the middle of a wide open strath—is

at first of a peculiarly rich yellow or golden bronze tint, attracting the

eye of the most unobservant visitor to the district. The history of this

tree is unrecorded, but tradition reports that it was brought from the

East by a monk when it was a mere sapling, and planted where it still

stands, the site being then within the church lands, and probably garden

ground, of the provostry or collegiate church founded by Sir John

Forrester there in 1429. The trees in its immediate vicinity indicate the

presence of an old garden having at one time existed around the spot,

there being still some remains of large and old yew and holly trees, and

also a few fruit trees. The present dimensions of this remarkable and

noteworthy tree are as follows:—73 feet in height; length of bole, 22

feet; and 13 feet in girth at 5 feet from the ground. It has recently been

banked up with earth round its base to form a rockery for Alpine plants

and ferns by the villa proprietor, in whose garden it now stands, and no

measurement at a lower point is obtainable. Many young trees have been

propagated from this parent tree by grafting and budding, and have all

maintained the peculiar golden foliage in spring, quite distinctly; but

plants raised from seeds shed by the tree, of which there are very few,

the parent being a shy fruit-bearer, vary much, some being blotched and

sometimes streaked with lighter variegation, while others have shown no

apparent difference from an ordinary sycamore in foliage. They all,

however, retain the parent's habit of being in leaf in spring considerably

earlier than the other varieties around them. [Wilder

this tree, on 26th August 1679, Lord Forrester fell, murdered by his niece

by a first marriage, Mrs Christian Nimmo, daughter of Mr Hamilton of

Grange, by the Hon. Mary Forrester, and wife of James or Andrew Nimmo, mer-chants

in Edinburgh.—R. H.] We ought, perhaps, here to notice another

sycamore which presents the same early bronze golden foliage as the

Corstorphine tree; it grows in the manse garden at Liberton, near

Edinburgh, in the south-west corner, and is in spring quite conspicuous at

some distance off by its rich and early bronze foliage and dense round

head. It is also evidently an old tree, but it is not so tall or

wide-spreading as the Corstorphine tree, apparently owing to its having

been placed in a crowded situation, for it seems to be of a similar age to

the Corstorphine sycamore. It is remarkable that Dr Walker, in his

industrious search and records of old and remarkable trees, does not

notice this tree, while he gives details of two sycamores growing at

Redhall, within a few miles from Corstorphine, in no way very remarkable

for size at the time he measured them—the one being at 4 feet high only 8

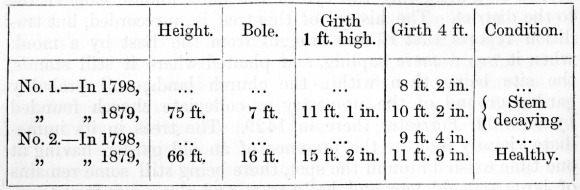

feet 2 inches, and the other 9 feet 4 inches when he wrote. These two

trees are still extant, and measured on 13th September 1879—eighty-one

years after Walker—they are as follows:—

These measurements show that in a period of eighty-one

years, or rather of eighty-one "growing seasons," these trees have

increased in the circumference of their trunks on an average—for No. 1, of

0.271 inches; and for No. 2, of 0.358 inches annually. This is probably a

very fair approximate average of the usual increment to the trunk of a

tree of the sycamore variety when already what may be termed full

grown—that is, after it has ceased to increase perceptibly in height, and

has assumed the rugged bark of a full-grown, or rather of a

fully-developed tree. The difference between the two trees in point of

increase of bulk may easily be understood, when it is stated that No. 1

has for many years shown symptoms of oozing from the stem, thus naturally

draining much of its vital sap away, and so hindering the healthy deposit

of young wood annually; whereas this has not been the case with No. 2,

which is reported to be still quite vigorous, and evincing no symptoms of

any decay.

Amongst the remarkable sycamores which have attracted

the attention of previous writers, probably the most notable is that known

as the "Kippenross Plane Tree." This venerable specimen is now no more,

having some years ago been snapt across a few feet above the ground by a

gale. This tree is not noticed by Dr Walker, but it is depicted by Nattes

in "Scotia depicta," and he gives its girth in 1801 as being 28 feet 9

inches. This measurement must have been taken at the ground line, for in

1798, at 5 feet from the ground, it was 22 feet 6 inches in circumference.

This tree was long reported to be the largest tree in North Britain; but

this distinction is really due to the large chestnut at Finavbn in

Forfarshire, recorded in vol. xi. of the Highland Society's

"Transactions," p. 43, and now also numbered with the past. Little

authentic information remains regarding the Kippenross tree; of its age

the Earl of Mar communicated the following particulars to Mr Monteath,

author of the "Foresters' Guide":—"Mr John Stirling of Keir, who died in

1757, and made many inquiries of all the old people, from eighty to ninety

years of age, which takes us hack to the reign of Charles II. near the

Restoration, says, they uniformly declared that they have heard their

fathers say that they never remember anything about it, but that it went

by the name of the big tree of Kippenross."

Mr Strutt in his magnificent work on old trees, notices

a sycamore at Bishopton, in Renfrewshire, opposite Dumbarton Castle, which

he figures in "Sylva Scotica," published in 1830, and of which he reports

the girth at the ground to be 20 feet at that date, and to be " a stately

wide-spreading tree" about 60 feet high. From recent inquiry no trace of

this goodly specimen is now to be found. Another remarkable sycamore of

which former notices have appeared, and which possessed a curiosity

peculiar to itself, was the tree at Calder House. This tree, Dr Walker

observes, "stands in the pleasure ground, on the road from the house down

to the church." On 4th October 1799 it measured 17 feet 7 inches at 4 feet

from the ground. It was called " Knox's Tree," and is known to have been

planted before the Reformation. It was the tree to which for many years

the iron "jougs" of the church were fastened. It came gradually to grow

over them, and for a considerable time prior to 1799 they had become

completely enclosed in its trunk. At the place of their imprisonment a

huge protuberance had formed on the south side of the tree, and at a

height of between 4 and 5 feet from the ground. From minute inquiries made

about two months ago, no trace of this tree can now be found, nor does

there appear-to be any record preserved of the ultimate fate of this

historical tree or of its embedded relic. Others, in the lists preserved

by Dr Walker and Sir T. D. Lauder, have also disappeared without any

record of the time or nature of their removal, a matter much to be

regretted in itself, the more so when it is considered that in most

instances the only opportunity of accurately fixing the age of the tree

has thus been lost.

But, while we have cause to regret the disappearance of

many of these old recorded sycamores, it is a subject of gratification to

be able to point to and identify others which still exist, and to contrast

their dimensions now with those of the earlier records. Many of these will

be found in the columns of the appendix to this report. Amongst the most

noticeable of these, is the sycamore at Cassillis in Ayrshire, which has,

as far back as the past two centuries, gone by the name of the "Cassillis

Dool Tree." It stands about 40 feet from the west end of Cassillis House.

At the top of the bole, which is only 8 feet 6 inches high, its head

branches off horizontally into 15 large boughs, forming a fine large

spreading top. The diameter of the spread of its branches is 76 feet.

There is an artificial mound of earth round the base of the tree, 3 feet

in height, and all the measurements recorded in our appendix have been

taken above, and starting from that point. It is reported to be above

three hundred years old; and has always been known as the "dool" tree, or

tree of grief. Some of the most remarkable old sycamores and trees of

other varieties enjoy the same name; its origin being in the fact that in

early times they were used by the powerful barons as gibbets for hanging

their prisoners taken in foray, or their refractory vassals. Their use

seems to have been more common in this way in the western districts of

Scotland. There are three so-called trees still existing in Ayrshire, all

of which formerly belonged to the powerful family of Kennedy;—the one at

Cassillis already referred to, and the other two at Blairquhan, the

largest of which is 72 feet in height, and 17 feet 8 inches in

circumference at 10 feet from the ground. The other is somewhat smaller in

dimensions. The date on the old escutcheon on the adjoining courtyard is

1573, to which period probably the planting of these trees may be

referred. It may be interesting here to narrate briefly the incidents of

the last occasion on which the Cassillis dool tree was so used. It

occurred above two hundred years ago, when Sir John Faa of Dunbar and

seven of his followers were hanged on it, for having attempted, in the

guise of a gipsy, to carry off the then Countess of Cassillis, who was the

daughter of the Earl of Haddington, and to whom he had been betrothed

prior to his going abroad to travel; but in his absence, he having been

made a prisoner and detained in Spain, and supposed to have died, the lady

married John, Earl of Cassillis. It is said that the lady witnessed the

execution of her former lover from her bedroom window. The old sycamore at

Ninewells, Berwickshire, mentioned also by Walker, and in a later

catalogue published in 1812, girthed 17 feet at a little below the

bows. It still exists, though decaying, and has always been popularly

known by the country people as "old hangie," from the tradition of its

having been used as a gibbet in olden times.

The remarkable old sycamore standing near the ruins of

the old castle, and on its west side, at Lochwood, Dumfriesshire, girthed,

on 29th April 1773, 8 feet 9 inches at 5 feet; and measured, on 5th

October 1879, it was 17 feet 7 inches and 13 feet 4 inches at 1 foot and 5

feet respectively. "In 1773," says Walker, "it was a fresh vigorous tree,

about 50 feet high, and not in the least 'wind-waved,' though in a very

high and exposed situation." It would have gratified the old Professor to

have known that in 1879 it would be still quite vigorous. The altitude of

its site is about 900 feet.

Near Dalbeattie, in the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright,

there stands a sycamore, which is recognised as a known landmark for miles

around, and is called the Hopehead tree. It is growing alone in

good dry soil, rather sandy, with a rocky subsoil; and in appearance is a

complete mushroom, with a short stem, and a wide-spreading flat head,

reaching to upwards of 70 feet in diameter. It girths 14 feet 6 inches and

13 feet at 1 foot and 5 feet respectively. We have been unable to trace

any tradition regarding this solitary and peculiar tree, although most of

such examples have some story or legend regarding their origin. At Foulis

Wester, in Perthshire, in the centre of the village, standing on a slight

knoll about 4 feet higher than the surrounding ground, is a very large and

old sycamore which girths 17 feet and 14 feet 2 inches at 1 foot and 5

feet respectively, with a bole of 14 feet. On inquiring as to the

existence of any legend in connection with this tree or its site, we only

ascertained that tradition reports that "a Man of Foulis planted it on ae

Sabbath nicht, wi' his thoomb!" This village arboriculturist must have

literally believed in the old saying, "Aye be stickin' in a tree,"

which accordingly perhaps does not owe its origin to Sir Walter Scott's

creative brain!

In other parts of Perthshire notable examples of the

sycamore are to be seen. For example, at Birnam, on the banks of the Tay,

near to the east ferry of olden times, there is still standing a majestic

sycamore, and near to it a venerable oak, which are said to be the last

remnant of the celebrated Birnam Wood, referred to by Shakespeare in the

play of Macbeth. This tree measures at 1 foot from the ground 23 feet 9

inches, at 3 feet it is 19 feet 9 inches, and at 5 feet it girths 18 feet

11 inches. In 1863 it measured at 3 feet high 19 feet, so that, though an

old tree, it is still increasing, and making new wood in its trunk. A

large hole which was noticed in the bole, in 1803, has now entirely filled

up, and the tree still seems quite vigorous. A very fine sycamore hitherto

unobserved, is growing on the Logiealmond estate of the Earl of Mansfield.

It is a magnificent massive specimen, girthing 11 feet 2 inches at 5 feet

from the ground, and it carries this circumference up the bole for 22

feet. It grows in a light loamy soil on a gravelly subsoil, and is 80 feet

in height with a clear bole of 28 feet. When Lord Mansfield purchased the

estate about thirty years ago, this tree, Mr M'Corquodale reports to have

then contained 309 cubic feet of timber, and, being still a healthy

vigorous tree, he estimates that it has added at least 2 cubic feet to its

bulk per annum, and it now contains fully 340 cubic feet. It stands in a

row of sycamores immediately on the side of one of the approaches to

Logiealmond House, the old main approach to which runs through an avenue

of lime, beech, and elm, which is perhaps one of the finest old avenues in

Scotland. At Inver-ardoch, near Doune, there are some very picturesque

groups of old sycamores of large size and great beauty. At Balgowan, in

Perthshire, at an altitude of 200 feet, we find a sycamore 85 feet in

height, with a bole of 28 feet clear, and 20 feet 1 inch in circumference

at 1 foot from the ground, and upwards of 15 feet at 5 feet from the

ground. Others of almost similar magnitude are noticed in the appendix,

growing at Abercairny and Castle Huntly, in this county, so rich in old

wood and so suitable for its growth and development; but we regret to add

that the largest and best trees have been mostly cut down at the last

named place for some years past. Towering above all other sycamores in

Perthshire, alike in height and bulk, are those at Castle Menzies, near

Aberfeldy, where probably the two finest and largest trees of this species

in Scotland exist. They grow at an elevation of 250 feet, in light sandy

loam, on a subsoil of sand. No. 1 is 104 feet 3 inches in height, with a

majestic bole of 35 feet in length, and is 25 feet 3 inches in girth at 1

foot, and 18 feet 4 inches at 5 feet from the ground. It stands in the

open park, and is a very noble looking tree. [Since

this paper was written, we regret to state that, in the disastrous "Tay

Bridge " gale of 28th December last, this splendid tree has lost two of

its largest side limbs. The symmetry of the tree is, however, little

impaired.—R. H.] No. 2 is one of a row of nearly similar size to

itself. It is 95 feet high, with a bole of 15 feet, when it divides into

two huge limbs, each being the size of an ordinary tree, and it girths

round its colossal conoidal base at 1 foot above ground 32 feet 5 inches,

and at 5 feet it is 17 feet 8 inches. In September 1778 this tree girthed

16 feet 8 inches at 3 feet high.

Many other instances and statistics might be given, but

a perusal of the figures and details tabulated in the appendix will be

found sufficient to convey a generally accurate idea of the diffusion of

this favourite tree in Scotland, and it would, therefore, be needlessly

repeating facts, were further extracts given, however interesting and

instructive these might be. It should not, however, be omitted to mention

in detail, those sycamores already alluded to in this report as " Queen

Mary's Trees," and one or two others of historical interest.

Queen Mary's sycamore at Scone Palace stands on the

lawn, directly under the drawing-room windows, and measures in girth at 1

foot from the ground, 14 feet 9 inches, and at 5 feet it is 13 feet 2

inches in circumference, and is 70 feet in height. In 1863 this tree

girthed 12 feet at 1 foot up, and was 60 feet high. At about 12 feet from

the ground, the trunk divides itself into two large limbs, which were of

equal size; but many years ago, one of these was blown off in a severe

gale, at a point about half-way up, leaving only the bare stump remaining

of that limb. The tree is consequently much disfigured, as nearly one-half

of its head has been carried away, along with the broken limb. This tree

has always been known in the memory of the oldest inhabitant as "Queen

Mary's Tree," and is believed to have been planted by the hands of the

hapless queen herself. There is also another old sycamore at Scone,

planted also before the drawing-room windows, which is currently believed

to have been planted by Queen Mary's son, James VI. It is now a very

picturesque lawn tree, with a short trunk and well-balanced head, and

girths at 1 foot from the base 14 feet 2 inches, and at 5 feet 12 feet 8

inches, and is about 60 feet high. Another sycamore, little known to the

public generally, although within a very short distance of Edinburgh, is

"Queen Mary's Tree," which stands on the north side of the old road

between Edinburgh and Dalkeith, about two miles from the city, and close

to the farm of "Little France." This hamlet is so named, from the fact

that during the residence, at the closely adjoining Castle of Craigmillar,

of the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots, many of her French retainers and

followers located themselves there; and it is interesting to note, that at

the present day, the occupants of one of the cottages by the roadside, are

named "Picard," and trace back for three generations their residence

there. This tree is called "Queen Mary's Plane Tree," and is the survivor

of two said to have been planted by the queen herself during her sojourn

at Craigmillar. Its neighbour, which was planted near the castle, was cut

down some years ago; but the tree we have indicated grows in full vigour

still, and at 1 foot from the ground measures in circumference 18 feet,

and at 4 feet 14 feet 11 inches, and at 8 feet 13 feet 10 inches; with a

tall and handsome bole of fully 20 feet in length, where the trunk divides

with huge limbs, with a wide umbrageous head, conspicuous a long way off.

It measured in height to its highest tip, in 1878, 84 feet 9 inches. On

the island of Loch Leven there is an old sycamore called "Queen Mary's

Plane Tree," which tradition asserts was planted by the queen while in

imprisonment there. It is now 12 feet 9 inches in girth at 5 feet from the

ground. Beside it grows an old thorn, also ascribed to the queen. The

original tree was blown down in 1850, but there is now a vigorous offshoot

from it fully 12 feet in height. The original hawthorn seems to have been

planted in what must have been the old garden to the castle, and was

always known as "Queen Mary's Thorn. Another old plane or sycamore, noted

as a Queen Mary tree, still exists, along with other living relics there

of the hapless queen, on the island of Inch-ma-home, on the lake of

Menteith. There can be no doubt whatever that it was planted a long time

subsequent to the date of the erection of the priory on the island in a.d.

1238, for along with several others, notably old trees, it and others have

been planted and arranged in lines to suit the walls and gateways of the

buildings. The one given in our appendix with a peculiarly rich red scaly

bark, stands opposite to an old Spanish chestnut and walnut, which is 80

feet in height, and 10 feet in girth at 1 foot, and 8 feet 1 inch at 3

feet high, and 8 feet at 6 feet high, and whose foliage is healthy, but

the stem of which is decaying, and oozing a good deal near the root. The

sycamore seems perfectly vigorous and sound, is now 13 feet 5 inches at 1

foot, 11 feet at 3 feet, and 11 feet 7 inches at 5 feet from the ground,

and 80 feet in height. It is called "Queen Mary's Tree," and near to it,

is Queen Mary's Bower. The quaint and simple arrangements of this

mediaeval garden are still quite apparent and visible. There are to be

seen three straggling boxwood trees,—evidently grown from the boxwood

edgings of a former oval flower-bed still discernible, and whose

lineaments are still visible. These trees are now 20 feet 6 inches in

height, and girth upwards of 3 feet at 1 foot from the ground, where they

diverge into several stems, probably the result of early pruning, and from

being kept clipt into form for edgings. In what has apparently been the

centre of the plot in this "bower," is a very quaint old thorn tree, about

22 feet in height, and 16 inches in girth, but it is much destroyed by the

prevalent west winds that sweep across the island, and to whose influence

it is much exposed.

From a glance at the appendix it will be apparent how

generally diffused has been the introduction of the sycamore in Scotland.

The list might have been increased, for there is hardly a parish in which

good specimens are not to be found; but we think enough has been tabulated

to give a very fair idea of the sycamore in Scotland at the present day,

and of the condition now of those old and formerly recorded trees we have

been able to trace, while not a few of goodly size, and which hitherto

have been unknown or unnoticed, have been registered for preservation and

future observation.

Of the few reported from England, and which have only

been taken by way of contrast, we should notice the tree at Cleeve Abbey

near Dunster, in Somerset. It is a strikingly picturesque old tree,

growing out of the base of a cross, which had belonged to the old

Cistercian Abbey there; the stones showing octagonal sides being still

visible at its roots. It is nearly 60 feet in height, and measures 18 ft.

3 in. at 1 foot from the ground. Near by stands a very handsome and

venerable walnut, probably of the same age, and now 19 ft. 8 in. at 1

foot, and 16 ft. at 5 feet from the ground.

Of the variegated variety of sycamore, good examples

exist at the Duke of Athole's grounds at Dunkeld, also at Dollarfield in

the valley of the Devon, at Gordon Castle, and at Mount Stuart in Bute.

The purple-leaved sycamore is another very beautiful variety. Large trees

of it, however, are very rare as yet, and we have fallen in with none of a

size worth recording amongst the old and remarkable trees of Scotland.

Probably the best specimens of this variety are those at Auchans Castle,

near Dundonald, in Ayrshire.

Of the other Acers in Scotland, there is a very

good specimen of the bird's eye maple {Acer saccharinum) at

Loganbank, Glencorse, in Midlothian, girthing 6 ft. 9 in. at 3 feet from

the ground. Also at Biel, Haddingtonshire, a tree of this variety is 11

ft. in girth at 1 foot, and 9 ft. 6 in. at 5 feet above the ground. It is,

however, a good deal disfigured by having lost a heavy limb, which has

spoilt the fair proportions of its head and contour. Many large trees of

the Norway maple (A. plata-noicles) exist in different parts of the

country, but, as it is a distinct species from the sycamore, though

resembling it considerably, we have not tabulated its statistics with

those of the sycamore.

Before concluding these observations on this

interesting and popular tree, we may mention here the account of an

experiment made upon it at Carron Park, in Stirlingshire, on 7th and 8th

March 1816. "To prove the capability of the sycamore yielding sugar,

incisions were made at 5 feet from the ground in the bark of a tree about

forty-five years old. A colourless and transparent sap flowed freely, so

as in two or three hours to fill a bottle capable of containing 1 lb. of

water. Three bottles and a half were collected, weighing in all 3 lb. 4

oz. The sap was evaporated by the heat of a fire, and gave 214 grains of a

product, in colour resembling raw sugar, and sweet in taste, with a

peculiar flavour. After being kept fifteen months, this sugar was slightly

moist on the surface. The quantity of sap employed in the evaporation was

24,960 grains, from which 214 grains of sugar were obtained; therefore,

116 parts of sap yielded one part of sugar."

The commercial value of the timber of the sycamore has

advanced very much during recent years, and at some sales of growing trees

within the past few years as high as £35 and £40 per tree has been

obtained for large trees. It is extensively sought after for the

manufacture of printing rollers, and turnery purposes.

Appendix