|

By James Macdonald, Aberdeen.

[Premium—Thirty Sovereigns.]

Excepting Caithness, Sutherland is the most northern

county in the mainland of Scotland. It is situated between 57° 53' and 58°

33' N. latitude, and between 3° 40' and 5° 13' W. longitude from London.

It is separated from Caithness on the east by a winding range of hills,

and from Ross-shire on the south and south-west by the Dornoch Firth and

the river Oikel, and some smaller streams. On the south-east it is washed

for a distance of about 32 miles by the Moray Firth; on the west, for over

40 miles by the Minch, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean; and on the north, for

about 50 miles by the waters of the Northern Sea. In form the county thus

presents five sides, the longest, about 52 miles, being the south and

south-west side, and the shortest, about 32 miles, that on the south-east.

The extent is variously estimated—in the Return of Owners of Lands and

Heritages, at 1,299,253 acres; and the Board of Trade Returns at 1,207,188

acres, or the seventeenth part of the whole surface of Scotland.

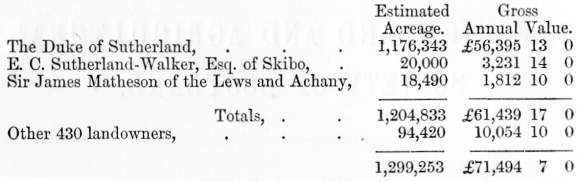

From the Parliamentary Return of Owners of Lands and

Heritages in Scotland, compiled in 1872-3, it is seen that in Sutherland

there are 433 owners of land, the total area of whose property is

estimated at 1,299,253 acres, and the gross annual value at £71,494, 7s.

Though, according to this estimate of its size, it is exceeded in extent

by only four counties in Scotland, Sutherland has the smallest number of

proprietors, with the exception of the small divided county

of Cromarty. It stands thirtieth in regard to gross annual value. Of

owners of land whose property extends to or exceeds 1 acre, it claims 85,

while of owners of 100 acres and upwards (excluding railway proprietors)

it has only 23, the total area of whose property is estimated at

1,297,301, and the gross annual value at £65,949, 7s. Eleven proprietors

exceed 1000 acres in extent; the gross annual value of six exceeds £500;

while only three Sutherland owners draw over £1000 a-year from land in the

county. These latter three are:—

It will thus be seen that while it is not absolutely

correct to say that the Duke of Sutherland owns the whole of the county

whose name he bears, His Grace's dominions in the far north have wide

limits. He in fact not only owns by several times the largest landed

property in the United Kingdom, but possesses more than nine-tenths of the

fifth largest county in Scotland.

The Valuation Roll for 1878-79 shows that the gross

annual value of the county, exclusive of railways and the royal burgh of

Dornoch, was £87,795, 3s. 2d.; that the annual value of railways amounts

to £7144; and that the annual value of the burgh of Dornoch is £874, 10s.;

making in all, £95,813, 13s. 2d. The Board of Trade Returns for the

present year (1879) state the area under all kinds of crops, bare fallow

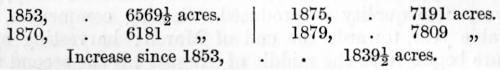

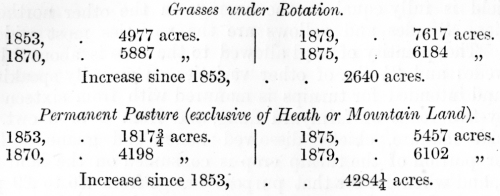

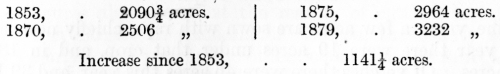

and grass, at 29,441 acres;—wheat, 27; barley or here, 2268; oats, 7809;

rye, 87; peas, 44;—total under cereals, 10,235 acres. The acreage under

green crops was—potatoes, 1929 acres; turnips, 3232; mangold, 1; rape, 19;

vetches or other green crops, 46;— total of green crops, 5227 acres. The

area under grasses in rotation is 7617 acres, and of permanent pasture,

exclusive of heath or mountain land, 6102. Of bare fallow there were 260

acres.

The Norse Teutons who, prior to the twelfth century,

had settled in Caithness, and frequently plundered farther south, gave the

name of Sutherland to this county, from the fact that it formed the

southern limit of their possessions. Indeed, it is barely a century ago

since it was separated from the sheriffdom of Caithness and formed into a

sheriffdom by itself. It contains thirteen parishes, and, in addition,

part of the parish of Reay extends across the Caithness boundary into this

county. It sends one representative to Parliament, the sitting member

being the Marquis of Stafford; while the royal burgh of Dornoch joins with

Dingwall, Tain, Cromarty, Wick, and Kirkwall in electing another. Mr John

Pender at present occupies this latter seat.

Dornoch is the only royal burgh in the county. It was

created so by Charles I. in 1628, and is mentioned frequently in ancient

northern history. The circumstance which, according to tradition, gave to

Dornoch the name it now bears is so peculiar as to deserve notice. Dornoch

is derived from the Gaelic words Dorn-Eich, which signify a horse's

foot or hoof; and a writer in the "Old Statistical Account of Scotland"

says—"About the year 1259, the Danes and Norwegians having made a descent

on this coast were attacked by William, Thane or Earl of Sutherland, a

quarter of a mile to the eastward of this town. Here the Danish general

was slain, and his army beaten, and forced to retire to their ships, which

were not far distant. The Earl of Sutherland greatly signalised himself

upon this occasion; and appears, by his personal valour and exertion, to

have contributed very much to determine the fate of the day. While he

singled out the Danish general, and gallantly fought his way onwards, the

Thane, being by some accident disarmed, seized the leg of a horse, which

lay on the ground, and with that despatched his adversary. In honour of

this exploit, and of the weapon with which it was achieved, this place

received the name of Dorneich, or Dornoch, as it is now called. This

tradition is countenanced by the horseshoe, which is still retained in the

arms of the burgh." Dornoch boasts of a beautiful cathedral which,

according to Sir Robert Gordon's "History of Sutherland" (1630-32), was

founded by St Bar, Bishop of Caithness, in the eleventh century. Gilbert

Murray, consecrated Bishop in 1222, transformed the original church into a

magnificent cathedral, which unfortunately was reduced to ruins by fire in

1570 by John Sinclair, Master of Caithness, and Iye Mackay of Strathnaver,

who, taking advantage of the minority of Alexander, Earl of Sutherland,

besieged and plundered Dornoch with a small army from Caithness.

Fortunately the old tower was saved, and so also were some fine Gothic

arches, but the handsome stone pillars that supported the latter were

destroyed by a terrific gale of wind on the 5th November 1605,—the day, by

the way, on which the Gunpowder Plot was discovered. The Earl of

Sutherland partially repaired the cathedral in 1614, so as to make it

suitable as a place of worship, and in 1863 the late Duchess-Countess of

Sutherland re-erected the edifice, and embellished it with even more than

its former grandeur. The Sutherland family have a burying place within the

cathedral, and in the east aisle are a beautiful marble statue of

the first Duke of Sutherland, by Chantrey, and a tablet to commemorate the

many virtues of the Duchess-Countess of Sutherland, both of whose remains

lie in that aisle. Sir Robert Gordon states that all the glass required

for the church erected by St Bar was made by St Gilbert, at Sidry, two

miles west from the town of Dornoch; and that adjoining this church Sir

Patrick Murray, between the years 1270 and 1280, established a monastery

of Trinity Friars. Since the commencement of the present century the town

of Dornoch, like the whole of the county, has been vastly improved. Little

more than fifty years ago there were a good many feel or turf

houses in the burgh, and now the buildings are as a rule neat and

commodious, built of stone and lime and slated. Several of the more

important buildings indeed are very handsome, and would do credit to a

much larger town. Situated as Dornoch is in an out-of-the-way angle of the

county, its trade is limited, and in 1871 its population was only 625. The

scenery around Dornoch is very beautiful, and regarding its links Sir John

Sinclair says—"About the town along the sea-coast there are the fairest

and largest links, or green fields, in any parts of Scotland, fit for

archery, golfing, and all other exercise. They do surpass the fields of

Montrose and St Andrews." The thriving modern village of Clashmore lies

about three miles north of Dornoch, and near to it stands Skibo Castle,

the handsome residence of Mr Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker of Skibo. A

castle with garrison, under the charge of a general officer, formerly

stood for centuries on the site of this mansion, and history and tradition

tell us that around it many a bloody conflict took place. In 1650 the

brave but ill-fated Marquis of Montrose, after his defeat by the

Presbyterian army near Bonar Bridge, and capture and betrayal by Neil

Macleod of Assynt, lodged two nights as a prisoner in Skibo Castle.

Twelve and a half miles along the coast northwards lies the beautifully

situated prosperous village of Golspie, with a population (1871) of 1074.

As in Dornoch, the majority of the dwelling-houses in Golspie were, at the

beginning of the present century, of the most primitive description, and

the inhabitants were chiefly fisher people. Now, however, its houses are

all substantial and comfortable, many of them very large and handsome. It

is entitled to be ranked as the most prosperous village in the county. A

convenient pier, accessible at low water, constructed by the Duke of

Sutherland at Little Ferry, about three and a half miles distant from the

village, has proved a great acquisition. Both by road and rail Golspie is

also well-appointed.

Dunrobin Castle, the chief seat of the Sutherland

family, and, without doubt, the most magnificent of all the many mansions

in Scotland, sits majestically on a beautiful spot on the sea-coast about

a mile north of Golspie. Part of the castle is said to be the oldest

inhabited house in Britain, but a great portion is of modern construction,

having been erected between 1845 and 1851 by the second Duke and Duchess.

The style of architecture is chaste and elegant, while the interior is, if

possible, still more grand, the paintings and other works of art being

numerous and of great value. The policies are extensive and beautiful; and

the wardens lying between the castle and the sea, "remarkable alike for

their extent, beauty, and productions." From the higher windows of the

castle the view is extensive, varied, and picturesque. Overlooking the

castle stands the romantic Ben-Bhraggie, on the top of which there is a

monument 70 feet high, surmounted by a colossal statue 30 feet high, of

the first Duke of Sutherland, who died in 1834. This monument, erected by

Her Grace's tenantry and friends, is said to have a higher site (1300

feet) than any other monument in the kingdom. Nearer there are handsome

monuments of the second Duke and Duchess and other members of the noble

family of Sutherland, all of whom have served well their day and

generation.

At Brora, in the parish of Clyne, there is a prosperous

growing village, fostered mainly by improvements and various works carried

on by the Duke of Sutherland. The village of Helmsdale, situated at the

mouth of the river of that name, has a larger population, chiefly

dependent on the herring fishing. There are numerous other small villages

throughout the county, that of Tongue on the west coast being snugly

situated amidst the most charming of Highland scenery.

The general configuration of Sutherland is wild and

mountainous in the extreme. Along the south-east coast there is a flat

fertile border, varying from little more than half a mile to over two

miles and a half in breadth, laid off in well-appointed farms, and

yielding profitable crops. The coast on the west and north, on the

contrary, is bare, bold, and precipitous, abounding in rocky promontories

and numerous inlets of the sea; while "the whole of the interior," says

one writer, "is mountainous, varied with elevated plateaus covered with

heath, vast fields of peat bog, some pleasant straths of average

fertility, watered by considerable streams and numerous lakes, embosomed

either in bleak dismal regions of moorland, or begirt by a series of hills

of conglomerate, whose naked and rugged sides have no covering even of

heather. Wildness and sterility are the great features of the landscape,

the dreary monotony being seldom relieved by tree or shrub; and this

uniformity of desolation is only occasionally broken by some glen or

strath presenting itself as an oasis of verdure in the bleak desert." This

picture, rough though it be, is in the main correct; but it barely does

justice to the straths, some of which, considering their high northern

latitude, are of more than average fertilitv, while a few of the lakes are

girt by beautiful fringes of natural wood, which have a

wonderful softening effect on the general sterility around.

Ben-More-Assynt reaches a height of 3235 feet; Ben-Clibrig,

3157 feet; and Ben-Hope, 3040 feet; while Ben-Laoghal (Loyal), Ben-Horn,

Ben-Bhraggie, and others follow, at lower elevations. Ben-Loyal, viewed

from the west or the north-west, is considered one of the most beautiful

mountains in the British Isles, and has engaged the brush of not a few

noted artists.

There are "literally hundreds" of lochs in the county,

and in all they are estimated to cover close on 34,000 acres. The -larger

are—Loch Shin, 16 miles long and about 1 mile broad; Loch Assynt, 8 miles

long and 1 mile broad; Loch Naver, Loch Hope, Loch Loyal, and Loch More.

Naturally, from the narrow limits of the northern peninsula, of which this

county forms the southern portion, the river courses are short, but some

of them —those that flow through lakes—discharge more water than many

rivers that run over twice as great a distance. The four larger

rivers—viz., the Oikel, Fleet, Brora, and Helmsdale rivers —flow eastward

into the Dornoch and Moray Firth sections of the German Ocean. The Oikel,

flowing out of Loch Ailsh, and receiving its tributary, the Shin, at

Invershin, is an excellent salmon and trout river, and forms the boundary

line between Boss and Sutherland for close on 30 miles. The Fleet is

formed by some small streams in the parish of Rogart, and after a short

run expands into Loch Fleet, which joins the firth at Little Ferry, a few

miles south of Golspie. Brora has its source in the parish of Lairg, and,

including the loch, it is about 24 miles in length, or about 4 miles more

than the course of the Helmsdale river. The principal rivers on the west

coast are the Halladale, which rises in the heights of Kildonan, and,

after threading through a beautiful strath close on 20 miles in length,

empties itself into the North Sea at Melvich; the Naver, which has its

source in Loch Naver, which is about 24 miles in length, draining the most

beautiful and valuable strath in the county; the Dionard, Kirkaig, and

Inver. The smaller streams are innumerable.

So high an authority as Mr J. Watson-Lyall asserts that

Sutherland is, "without exception, the best angling county in

Scotland—especially for trout......Many of the lochs of Sutherland are

splendid sheets of water, and many are nameless mountain tarns; but even

those least inviting in appearance hold lots of trout. No one who wants

really good trout-fishing should hesitate to penetrate into Sutherland."

The greater number of the lochs and streams can be fished for trout by

strangers who are guests at the hotels on the Duke of Sutherland's

property. On many of the lochs and rivers there is also good

salmon-fishing, but in most cases it is let to shooting or other tenants.

The Duke of Sutherland has for several years carried on at Brora, under

the management of Mr Dunbar of Brawl Castle, extensive experiments on the

breeding of salmon; and, by introducing into the streams of Sutherland the

salmon of such rivers as the Tweed, the Tay, and the Thurso, he has very

greatly increased the value of the salmon fishing on his property. To

those who prefer the gun to the rod there is also strong attraction in

Sutherland. It contains many excellent grouse moors and a few good deer

forests. The largest of the latter is Reay Forest, rented by the Duke of

Westminster at £1290.

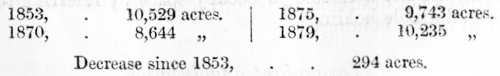

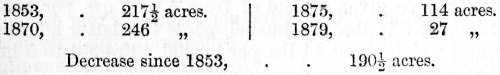

Sutherland stands twenty-third in Scotland in regard to

the area under wood. In 1853 that area was estimated at 10,812¾ acres, but

according to a Board of Trade Return in 1872 it was then only 7296 acres.

The natural clumps of shrubbery along the straths in the interior have

been gradually disappearing, and it may be that a greater area of these

was included in the estimate of 1853 than in that of 1872. About the

beginning of the present century, the extent under plantations of fir and

hard wood was estimated at about 936 acres, and under natural wood or

shrubbery, in the straths of the several rivers and rivulets, at

1350—making in all, 2286 acres. Between 1836 and 1842, new plantations,

extending to 2091 acres, were formed under the direction of Mr James Loch,

commissioner to the Duke of Sutherland, at a total cost of £2344; and an

interesting report on the improvement will be found in vol. i. 3d series,

of the "Transactions of the Highland and Agricultural Society," p. 36.

Since 1872 the area under wood has been considerably increased by new

plantations formed in connection with the land reclamations. These

plantations will be referred to hereafter.

When it is mentioned that, according to a liberal

estimate, barely one-twenty-fifth part of the county is capable of

being-cultivated, it will easily be understood that Sutherland does not

occupy a prominent position from a strictly agricultural point of view. In

regard to the total area under crops, bare fallow, and grass, it stands

twenty-ninth among the Scotch counties— Nairn, Bute, Selkirk, and

Clackmannan ranking below it. Nairn has a slightly greater area under

regular cultivation, but, on the other hand, Shetland has a less area

under rotation, so that, likewise from that point of view, Sutherland is

still left twenty-ninth in order. In reference to the proportion or

percentage of the total area of the county occupied by "crops, bare

fallow, and grass," it is lowest on the list. Another illustration of the

mountainous and sterile character of the main portion of Sutherland is

supplied by the fact that the total valuation of the county, as returned

in the Valuation Boll for 1878-79 (including railways and the royal burgh

of Dornoch), is equal to only about 1s. 7d. per acre—the lowest by far of

any of the Scotch counties. Limited, however, as is its arable area,

Sutherland has, in regard to the system of management pursued on most of

its farms, pushed itself, with commendable spirit, fully abreast of the

times. Indeed, on the larger and better arable farms of Sutherland, the

modern and improved systems of farming are carried out with as much

success and perfection as in the Lothians, or in any of the other better

favoured regions of Scotland. The wealth and reputation, however, of

Sutherland lies chiefly in its sheep farming, for which its long-winding

straths and wide mountain ranges are admirably adapted; and which is

carried on, not only on a very extensive scale, but also in a most

advanced, systematic, and successful manner.

As shall be afterwards shown, Sutherland was the last

county in Scotland to be opened up, as it were, to free intercourse with

the outer world. Indeed, up to the commencement of the present century, it

may be said to have been locked up by water and mountain. But now, both

internally and with the world beyond, it enjoys ample means of

communication. By the liberality and enterprise of the Duke of Sutherland,

the Highland Railway was extended to Golspie in 1868, and to Helmsdale

three years later; while in 1874 the same line was continued to Wick and

Thurso. The active laudable interest His Grace has taken in the conferring

of the inestimable boon of a railway system on the Highlands of Scotland

is well testified by his contributions towards that object, which are

stated at £301,000. The line from Bonar Bridge to Golspie cost him

£116,000, and from Golspie to Helmsdale, £60,000, while he contributed

other £60,000 towards the extension of the system to Caithness. It is

worthy of mention, that in the formation of the line from Golspie to

Helmsdale, the Duke acted as his own contractor, the work having been

carried out under his own personal supervision.

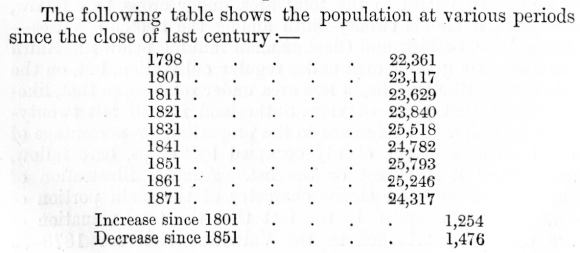

Population.

It is not the writer's intention to discuss what are

known as the "Sutherland clearances." Fitly termed a " vexed question," it

is outside the legitimate scope of this report, inasmuch as the operations

so named occurred about sixty years ago. It may just be explained, in a

word, what these clearances really were. Previous to 1811, the various

straths that intersect the county were peopled more or less densely by a

class of small tenants, who were dependent for their sustenance mainly on

potatoes and inferior and ill-fed cattle and sheep. Through severe

winters, which sadly thinned the ranks of their cattle and sheep, these

tenants and their families were frequently reduced to absolute dependence

on their landlords and other superiors for food sufficient to sustain

life. It was thought desirable that some change should be made in the

condition of the people, both for their own interests and with the view of

properly developing the resources of the county. The subject was remitted

by Lord Stafford, the first Duke of Sutherland, to eminent agriculturists,

who reported in effect "that the mountainous parts of the estate, and

indeed of the county of Sutherland, were as much calculated for the

maintenance of stock as they were unfit for the habitation of man;" and

that it seemed "as if it had been pointed out by nature that the system

for this remote district, in order that it might bear its suitable

importance in contributing its share to the general stock of the country,

was to convert the mountainous districts into sheep-walks, and to remove

the inhabitants to the coast, or to the valleys near the sea." The

movements thus indicated were carried into effect about the time already

mentioned,—between 1810 and 1820,—the great bulk of the small tenants and

their families having been settled near the coast, where a limited piece

of land was allotted to each at a merely nominal rent. It is stated also

that a few, who preferred that step, were conveyed to Canada at Lord

Stafford's expense; but it is denied that the population of the county was

reduced to any appreciable extent by emigration due to these "clearances."

As to what extent the removing of these small tenants from the interior to

the coast has affected the population of Sutherland, I shall not hazard an

opinion; but it may be observed, in treating of this portion of the

subject, that the manner in which the county is mainly occupied, as

sheep-walks and deer forests—chiefly the former—naturally implies a

"maximum of territory, with a minimum of industry and population." Captain

John Henderson, in his admirable work on the "Agriculture of

Sutherland," published in 1812, calls the county "a nursery of brave,

hardy Highlanders," but they have now become scarce; and in bringing about

the change there have no doubt been more agencies at work than emigration

and the introduction and extension of sheep-farming,—such, for instance,

as the abolition of private or "family" regiments, and the high rate of

wages in the south.

The inhabited houses in 1871 numbered 4814, so that

there is rather more than an average of five persons to each house. Of the

population in 1871 there were 11,408 males and 12,909 females. The present

population is equal to about one person for every 50 acres, the proportion

of land to each person in Boss and Cromarty being exactly one-half of that

extent. What may be termed the natives of Sutherland, the descendants of

the "ancient inhabitants," like those of Boss and Cromarty, belong to one

or other of the branches of the Celtic race, and have pursued similar

habits in social life. Sutherland, too, has had a full share with its

neighbours in regard to invasion and plunder, the fierce Norsemen and the

Danes having made frequent raids on the county, leaving behind them

indisputable traces of their presence, as well as of the character of

their mission. In the parish of Golspie there are the ruins of three "Pictish

Towers," built and used, it is supposed, by the Danes. One of the three is

situated near Dunrobin Castle, and is in a wonderfully good state of

preservation. The north and west coast abounds with these ruins. One in

Strathmore, in the parish of Durness—"Donnadillee"—is the most perfect in

the county, the walls still standing to a height of 20 or 30 feet above

ground. Interesting, however, as they are, space cannot be devoted to

these points. Gaelic is still the "every-day" language of the older or

bona fide natives of Sutherland, not a few of whom understand very

little English, and can speak still less, or even none at all. But, under

the bracing current of national education, and the ever-increasing

intercourse between the inhabitants of the Highlands and other parts of

the country, the Celtic language is fast dying out, and perhaps, except

from a philological point of view, is doomed to extinction at no distant

date. Since the commencement of the present century, more particularly

during the past twenty-five years, a large number of farmers and others

from the south and north-east of Scotland have settled in Sutherland, and

these fresh infusions have materially modified the habits of the people,

as well as tended to hasten the demise of Gaelic. The dwelling-houses of

the smaller tenants have been greatly improved during the past quarter of

the century, chiefly by the proprietors; and there are now comparatively

few of those low, black, uncomfortable "feal" houses that were to be seen

everywhere throughout the county, even in villages and the royal burgh of

Dornoch, at the commencement of the present century. These small tenants

hold their lots of land at low rents, are as a rule sober and of good

moral character, and are more industrious, better educated, better fed,

and better clothed, as well as better housed, than when they were

scattered along the straths in the interior. Sutherland was long

ill-provided with educational machinery. About the commencement of the

present century it is stated that it had a Gaelic teacher in each parish,

paid at the rate of from £15 to £27 a-year, and that the number of

scholars was about 1012, or in the proportion of about 1 to every 21 of

the population. The Education (Scotland) Act, 1872, however, has supplied

all wants in this direction; and, though the school rates are high at

present, great advantages must flow from the superior education now being

diffused throughout the county. With parishes of so large an area and so

thinly spread a population, it has been found to be no easy matter to

carry out the Education Act properly in Sutherland, but the School Boards

of the county have displayed much care and ability, and have, as a rule,

done their work well. One difficulty was to know how to extend the

benefits of the Act to the families of shepherds who reside away among the

mountain ranges, perhaps 12 or 20 miles from the nearest school. This is

now being satisfactorily accomplished by female teachers, who "go the

round" of these outlying houses teaching a week or a fortnight in one

family, and a like period in another.

Climate.

The climate varies considerably in different districts

of the county. On the east coast, that is to say, on the narrow irregular

stretch of country that lies between the mountain range and the German

Ocean, the climate is dry and mild. Captain Henderson says, "Though the

east coast of Sutherland is 3° farther north than East Lothian, there is

much less difference between the two in regard to climate than could well

be imagined. The spring may be two weeks later, and the winter may

commence two weeks earlier, but the summers are equally warm, if not

warmer, and the winters not colder." Snow seldom lies long on the ground

in this part of the country, and the rainfall cannot be said to be heavy,

about 31 inches, or little over the average for Easter Boss. The

prevailing winds blow from the west and north-west, but the moisture they

absorb in their long course over the Atlantic Ocean is mostly deposited

among the broad range of hills and dales which are passed before the east

coast is reached. These winds, indeed, bring only occasional showers over

upon the east coast. The easterly winds, next in frequency, as a rule

bring rain and cloudy weather, sometimes very heavy falls of rain; but

these gales and rainfalls are usually succeeded by a period of mild dry

weather. The southerly winds, which are not frequent, are seldom

accompanied by rain. The land in some parts of the east coast, in a good

season, is ready for the seed by about the middle of March, when several

farmers commence sowing; and on the earlier farms harvest commences about

the middle of August, being general all along the east coast by the middle

of September. Among the hills in the interior of the county the climate,

as would be expected, is cold, boisterous, and wet, the winters being long

and severe, and the springs late and cold. Though a good deal of snow

falls during winter, it does not, as a rule, lie long to a great depth on

the ground. Last winter snow lay in the greater portion of the county to a

depth of nearly 2 feet for about four months, but it was one of the most

severe winters that have ever been experienced in the Highlands of

Scotland, and, excepting along the west coast, showed little partiality in

its visitation. In the straths which intersect the county the climate is

wonderfully mild. The valley of Kildonan, inland and mountainous though

that district is, is almost as mild and genial as along the east coast;

and, on the few irregular fields by the river side, oats are usually ready

for the sickle at least two weeks earlier than on an average farm in the

counties of Aberdeen and Banff. Frosts, however, visit the straths early

in the autumn, while, especially in those towards the west coast, a great

deal of rain falls. In the Assynt district the climate is moist, the

annual rainfall being about 60 inches. Owing to the sea breeze and the

influence of the Gulf Stream, snow does not lie long excepting on the more

elevated parts. Towards Durness the temperature becomes colder, more

particularly northwards from Cape "Wrath, where the influence of the Gulf

Stream is less felt than south of that bold promontory. Around Tongue the

climate is surprisingly dry and mild, the rainfall being only about 36

inches, and the mean temperature 45°. Snow seldom lies long near the

coast, and the winter, as a rule, is comparatively mild and open, spring

being generally more severe than winter owing to the prevalence of cold

northerly, north-easterly, and easterly winds, which often seriously

retard vegetation. In favourable seasons the grain is usually harvested by

the middle of September. On the higher lands near the west coast a great

deal of rain falls; but a heavy covering of snow seldom continues long.

The climate of Sutherland is generally regarded as very

healthy for both animal and vegetable life; indeed, Captain Henderson

states that "it is so healthy that one medical man is all that can earn a

livelihood from his profession in the county;" while it has been said

that, even as late as about 1840, apothecaries' drugs were almost never

called for. But now Sutherland has a larger share of both than in these

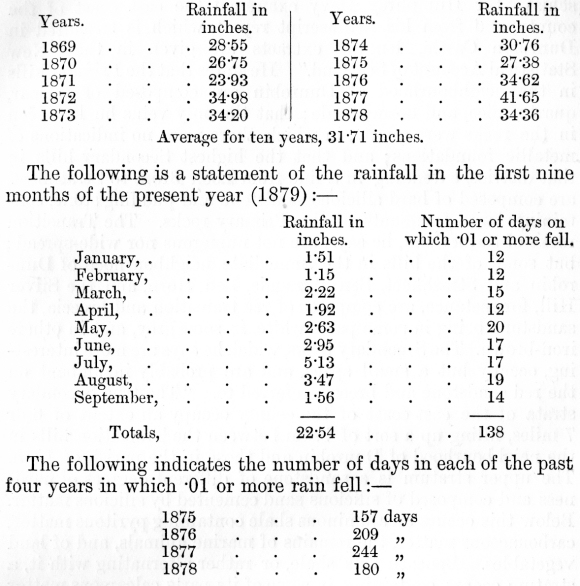

more primitive times. As already stated, the annual rainfall at Scourie,

in the Assynt district, on the west coast, is about 60 inches, and at

Tongue, on the northern coast, about 36 inches. The following table shows

the amount of the rainfall at the Dunrobin Castle Gardens in each of the

past ten years:—

Geology.—Soils.

The relations between underlying strata and surface

soils are generally so intimate that,

rule, a report on the agriculture of a county or district would be

incomplete without some sketch of the geological formation; but, in this

case, there are circumstances which make it undesirable to occupy space

with such an account. In the first place, the subject has already been

ably dealt with in the "Transactions of the Highland and Agricultural

Society" by Mr E. J. Hay Cunningham, M.W.S., whose admirable "Geognostical

Account of the County of Sutherland" appears in vol. vii., 2d series, p.

73. Again, the exceptionally small portion of the soil of the county that

is worked for agricultural purposes makes a lengthy sketch of its geology

less desirable than it otherwise would be. A few sentences will therefore

suffice. Generally speaking, it may be said that the underlying strata of

the county belong to the Primitive and Transition systems, the Primary

rocks consisting chiefly of coarse granite, gneiss, syenitic gneiss, and

mica-schist. Sir Humphrey Davy examined the east coast of the county, and

from his manuscript report, which is treasured in Dunrobin Castle, lengthy

extracts are given in the "New Statistical Account of Scotland." He states

that the Primary hills in the neighbourhood of Dunrobin are composed of

felspar, quartz, mica, and horneblende; that the only veins he had seen in

the rocks were quartz, in which there were no indications of metallic

foundations; and that the highest Secondary hills in that district,

extending in a line from Loch Brora to Strathfleet, are composed of hard

silicious sandstone and pudding stone, containing large fragments of the

Primary rocks. The Transition rocks of Sutherland, he says, are not

numerous nor wide-spread; but some of the hills in the immediate

neighbourhood of Dunrobin and Strathfleet, Ben Bhraggie, Ben Horn, and the

Silver Hill, for instance, are composed of red transition and breccia, the

sandstone being in some parts white, in some grey, and in others

iron-brown. The Secondary rocks, which he says are more interesting,

occupy but a small space, and are probably incumbent on the red sandstone

and breccia referred to. "The true Secondary strata of the east coast of

the county occupy an extent of 6 or 7 miles, filling up a sort of basin

between the Transition hills in the neighbourhood of Dunrobin and those in

the parish of Loth. The upper stratum is a sandstone of different degrees

of hardness and composed of silicious sand cemented by silicious matter.

Below this occurs an aluminous shale containing pyritous matter,

carbonaceous matter, the remains of marine animals, and of land

vegetables. Beneath this shale, or rather alternating with it, a stratum

occurs, containing in some of its parts calcareous matter and passing into

limestone, but in general consisting of a silicious sand agglutinated by

calcareous cement. The coal-measures occupy the lowest part of this

Secondary district which has yet been exposed. The hard sandstone is

principally composed of pure silicious earth. It is not acted upon by

acids, and is not liable to be decomposed by the action of air and water.

The shale contains no calcareous matter near its junction with the coal.

The limestones found in the Secondary strata contain no magnesian earth,

and are adulterated only with aluminous and silicious earths and oxide of

iron. They differ very much in purity in different parts." Another writer

says that gneiss composes at least four-fifths of the whole surface of the

county, and that the Old Bed Sandstone occurs in patches both on the

northwest towards Cape Wrath, and on the south-east along the Dornoch

Birth. In the last portion he says it is succeeded by one of the most

remarkable geological formations in Scotland, the Brora coalfield, in

connection with which there are strata of lias and oolite found in no

other part of Scotland, except a small patch on the west of the town of

Campbeltown in Kintyre and a few patches in the Western Isles. On the

north-west the rocky headlands consist of the Laurentian gneiss, while

above it "lie isolated mountains of Cambrian sandstone." There are also

strata of the Lower Silurian system, the limestones of which are wrought

for estate improvements, by the Duke of Sutherland, at Eriboll, on the

west coast, and at Shiness, on Loch Shin, in the interior.

As already stated, the arable land in the county is

confined mainly to a narrow fringe along the south-east coast. Here the

most general soil is a light sandy loam that yields liberally under

generous treatment. Between Bonar Bridge and Dornoch the soil is light

gravelly loam. In the parish of Dornoch it is clayey inland and sandy near

the sea, with an irregular belt of black loam intervening. The soil on the

arable land in the Golspie district varies from very light sand to medium

clay, the most general and best being loam with a slight admixture of

clay. Sir H. Davy says that the soils of the coast-side lands between

Little Ferry, a few miles south of Golspie, and Helmsdale, seem to be

formed principally from the decomposition of sandstone rock, which in some

parts approaches in its nature to shale. The soils in Strathfleet appeared

to him to have been produced by the decomposition of Transition sandstone

and breccias. Around Brora the soil is light and gravelly, but in Loth

there is some excellent heavy land; one hollow on the farm of Crakaig, in

particular, being covered with deep bluish clay. "Prior to the sixteenth

century," says Captain Henderson, "the river of Loth, as it emerged from

the mountains, turned due north, running parallel to the sea, at the

distance of about a quarter of a mile from it, through what is now called

the Yale of Loth, and there formed a swamp or marsh, divided from the sea

by sandy banks, until an enterprising Countess of Sutherland caused a

course to be cut for the river to the sea, through a rocky eminence." By

this means about 100 acres of excellent carse land were reclaimed, and

being well drained, it yields good crops of wheat, barley, oats, turnips,

and grass. Around Helmsdale the soil is light but fertile, while along the

Helmsdale or Kildonan Strath there are several small haughs of similar

soil, with rather less sand, that yield good crops of oats and turnips.

The soil on the higher banks along this strath consists of reddish gritty

sand and peat-earth, in which are embedded numerous detached pieces of

granite rock or pudding stone. In Strathbrora and Strathfleet there are

also several good small pieces of haugh land, some being of medium loam;

while in the parishes of Rogart and Lairg there is a considerable extent

of light gravelly loam, mixed with moss, and lying on a clayey subsoil.

Perhaps nine-tenths of the interior, however, is covered with peat-earth,

and there are many broad swamps of deep moss. The surface of the Assynt

district is so rough and rocky that, with the exception of a few spots

consisting chiefly of moss, it contains no land suitable for cultivation.

The same may almost be said of the parishes of Eddrachillis and Durness,

although there are several good patches of mixed gravel and moss, and a

few small pieces of fair loam. In Durness there are three farms—Balnakiel,

Eriboll, Keoldale—with arable land attached—150 acres to each of the two

former, and 100 acres to the latter. It is also a good grazing parish, the

limestone which underlies its surface-soil proving a valuable stimulant to

its pasture. The arable land in the parishes of Tongue, Parr, and Reay

lies mostly along the coast, and the soil on a few spots is good black

loam, on other parts sandy loam, but on the greater portion a varying

mixture of moss, gravel, and clay, which yields good crops under liberal

treatment. Along Strathnaver, the finest strath perhaps in the county,

there is a considerable extent of good haugh land, a mixture of sand,

gravel, and moss, which was for many years previous to 1820 cultivated by

over 300 families. On the banks of the river Strathy there are some

patches of thin fertile sandy land. In Strathhalladale there were at the

beginning of the present century about 300 acres of light soil, similar to

that in Strathnaver, cultivated in small holdings.

Condition of the County Seventy Years ago.

Sutherland was the last county in Scotland to throw off what may be called

the thraldom of the dark ages. After the other counties in the Highlands

had enjoyed improved communication with the world beyond, Sutherland still

lay in a manner locked up by sea and mountain; while devoid as it was of

what could be called roads, and consisting as it does almost entirely of

"one uninterrupted succession of wild mountain or deep morass," the

intercourse between the different districts within the county itself was

"confined exclusively, or nearly so, to the exertions of those who could

travel on foot, and even this mode of communication, except to the natives

who were brought up to such toil and exertion, was almost impracticable,"

not to say dangerous, "in passing precipices or struggling through

swamps." The proprietors and other leading inhabitants of Sutherland,

however, early availed themselves of the Act passed by Parliament in 1803,

giving aid in the construction of roads and bridges in the Highlands of

Scotland;—they even took the lead of their brethren in Ross, Cromarty, and

Inverness in the matter—and with commendable spirit set to work to open up

the county. The two main obstructions were the Dornoch Firth and Loch

Fleet but at last both were successfully overcome. Across the former at

Bonar, a very handsome bridge was constructed by Mr Telford at a cost of

£13,971. It consists of two stone arches of 50 and 60 feet span

respectively, and one iron arch of 150 feet span; while on the Ross-shire

side an extensive embankment had to be made. The work was begun in July

1811 and completed in November 1812. Mr James Loch, commissioner on the

Sutherland estates, in his interesting account of the Stafford

improvements, published in 1820, states that the iron portion of this

handsome bridge "was cast in Denbighshire, where it was first put

together, and then taken to pieces and re-erected in the furthest

extremity of the Highlands of Scotland, and exhibits in that remote

district a striking monument of national enterprise and liberality, and of

the public spirit of the county of Sutherland." The other arm of the sea

referred to,— Loch Fleet, or the Little Ferry,—lies between Dornoch and

Golspie. A mound, 999 yards long, 60 yards wide at the base, 18 feet in

perpendicular height, and sloping to about 20 feet wide at the top, was

formed at a narrow part of the channel, and at the north end was

constructed a substantially built bridge, 34 yards long, consisting of

four arches of 12 feet span each, and fitted with strong valve gates. The

total cost of this important undertaking amounted to about £9000, of which

£1000 was subscribed by Lord Stafford, and which Mr Loch estimates as the

probable amount by which the estate of Sutherland might be benefited by

excluding the flowing of the tide over some good land, and by obtaining

about 400 acres of beach, which may in time push out a rough herbage, and

thus gradually fit itself for culture." "While these gigantic works were

going on, the foundation of roads throughout the county was pushed forward

with much energy, so that "in the space of twelve years," says Mr Loch,

"the county of Sutherland was intersected in some of the most important

districts with roads, in point of execution, superior to most roads in

England." Previous to 1819 the mails were conveyed on horseback from

Inverness to Tain, and from thence across the firths by foot-runners; but

in July of that year a daily mail diligence commenced to run between

Inverness and Thurso. The counties of Ross and Caithness, and the Marquis

of Stafford on behalf of the county of Sutherland, contributed each £200

for two years in aid of this establishment; and, commenting upon the

movement, Mr Loch says, that "in the history of the country there is no

parallel of so rapid a change as has thus been effected in this distant

corner of the island. Passing at once from a state of almost absolute

exclusion from the rest of the kingdom to the enjoyment of the

incalculable advantages of the mail coach system, at a distance of 802

miles from the capital of the kingdom, and 1082 miles from Falmouth—the

farthest extremity in the other direction to which this establishment

extends; joining as it were by one common bond of intercourse the two most

distant parts of the island,—the one situated at the extremity of the

English Channel, the other on the coast of the frozen ocean."

The county having thus been opened up, it may be

interesting to glance back at the condition in which, in an agricultural

and social sense, the explorer would then have found it. Captain Henderson

estimates the area of the arable land in the county in 1808, that is to

say, land under wheat, bere, oats, pease, potatoes, turnips, and sown

grasses, at 14,500 acres. It appears that by far the greater portion lay

on the south-east coast, in the parts that form the main centre of the

arable farming at the present day, while along the straths intersecting

the county, and now under sheep, there were several thousands of acres

under cultivation. The total annual produce of these 14,500 acres was

estimated at £62,781, 2s. 8d., or a little over £4, 6s. 7d. per Scotch

acre. The yield per Scotch acre of wheat is stated at 7 bolls, worth 30s.

per boll or £10, 10s. per acre; bere, 5 bolls, worth 20s. per boll or £5

per acre; oats, 5 bolls, worth 15s. per boll or £3, 15s. per acre; pease,

at 4 bolls, worth 20s. per boll or £4 per acre; potatoes, 12 bolls, worth

8s. per boll or £4, 15s. per acre; turnips, worth £6 per acre; sown

grasses, 200 stones, worth 8d., or £6,13s. 4d. per acre. A thousand acres

of natural meadows, haughs, &c, are estimated to be worth £1, 6s. 8d. per

acre, while pasture for 4291 horses is estimated at 10s. each or £2145,

10s.; ditto for 17,333 cattle at 10s. each or £8666, 10s.; ditto for

94,570 sheep at 2s. each or £9457; ditto for 1123 goats at 1s. each or

£56, 3s.; and ditto for 270 swine at 3s. each or £40, 10s.;—in all for

pasturage (exclusive of £150 charged for 500 red deer in Reay Forest),

£20,365, 13s., which brings the total value of what is called the

agricultural produce of 1808 up to £84,630, 11s. 8d.

The same authority states that the farmers of

Sutherland at the period referred to were as diversified as the size of

their farms. None of them were bred to farming in a regular manner from

their youth,—the more opulent class were gentlemen who had been in the

army, navy, or some respectable line abroad, who farmed partly for

pleasure and convenience, and derived their profits from what they subset

to the lower class of cottars or small tenants; by far the most numerous

class were those whose fathers and grandfathers for many generations had

followed the plough, or the black cattle and the goats in the mountains,

men who never thought of changing or improving their condition, and whose

means and professional knowledge were too limited to admit of change or

amendment. The soil, climate, and short leases discouraged them, and,

until the sheep-farming circumscribed the extent of their hill pasture,

they were chiefly dependent for a bare subsistence on the rearing of black

cattle. As a rule they were "frugal and temperate in their habits in

spring and harvest they laboured hard, and the summer and winter were

passed in ease, poverty, and contentment." In these times land was let not

by the acre, but by the quantity of bere it required to sow it. A boll of

bere usually sowed an acre; and arable land was thus let by the boll

sowing, while the rent of pasture was calculated by the number of cattle

it would maintain in the summer months. The arable land is reckoned in

penny land, farthing, and octos. The penny land is generally allowed to

contain 8 acres; an octo, of course, is 1 acre or a boll sowing, but this

varies in proportion to the quality of the land— when of a superior

quality the quantity is less, and vice versa.

The wadsetters prevailed on the south-east coast, while

in the straths in the interior and on the western and northern coasts the

arable land was mostly let in small lots of from 1 to 30 acres or boll

sowings, each occupier having a proportion of intown pasture, while

"the mountains and moory hills were pastured in common by the cattle of

the nearest tenants." The wadsetters took an extent of ground equal to

about £200 Scots of valued rent, and occupied themselves from 30 to 50

bolls' sowing, letting the remainder to sub-tenants in farms of from £3 to

£5 rent, besides services which Captain Henderson says were in some cases,

unlimited. Mr Loch states that these wadsetters "exacted from their

sub-tenants services which were of the most oppressive nature, and to such

an extent that if they managed well they might hold what they retained in

their own possession rent-free. This saved them from a life of labour and

exertion. The whole economy of their farming—securing their fuel,

gathering their harvest, and grinding their corn—was performed by their

immediate dependents." In illustration of this statement, Mr Loch gives in

his volume an interesting account of the rent payable by the sub-tenants

of the farm of Kintradwell for the year 1811, from which the two following

specimens may be given:—"Leadoch,—Angus Sutherland—6 hens, 6 dozen eggs,

£4 in money, and 1 cover kiln-drying, clearing hay lands, shearing 48

stooks, threshing 12 stooks, 30 horses for a day leading ware, 4 days'

work in harvest in cornyard, 1 spade and 3 spreaders of peats, and 2 days

repairing peat road. Cottertown.—John Bruce—3 hens, 3 dozen eggs, £5, 1s.

3d. in money, and shearing 24 stooks, threshing 12 stooks, 2 days' work in

cornyard, 1 spade and 1 spreader of peats, 1 day at peat road, thatching

houses, clearing hay lands, 12 horses for 1 day leading ware, and half a

cover kiln-drying. The total amount paid as rent by sub-tenants on this

farm was,—in money, £145, 19s. 7d.; victual, £21, 11s. 3d.; hens, £3,

18s.; eggs, £1, 7s. 6d.; servitude, £56, 10s.;—making, in all, £229, 6s.

4d." Mr Loch explains that Kintradwell "had been granted in wadset or

mortgage for the sum of £800. In 1811 the wadsetter granted the residue of

the term then unexpired, being eight years, to the late sub-tenant, Mr

MacPherson, for a fine or grassum of £800, and the annual rent of £150.

The value of the land in Mr Macpherson's own occupation amounted to £200

per annum, thus making the whole income derived by him from the farm £429

per annum. In this case there were three gradations between the landlord

and the occupier of the land; in some instances, four." This obnoxious

system became less popular as the present century advanced, the chiefs or

landed proprietors found that they had more complete control over their

people if they were made their own immediate tenants, and in many cases

the proprietors remanded the wadsets or mortgages, leaving with the

farmers what they had retained in their own possessions, and letting the

remainder directly to the small tenants who were formerly the sub-tenants.

Captain Henderson states, that about the year 1808, the rent of the arable

land on the south-east coast was from 15s. to 21s. per boll sowing or

acre, while, in some cases, 30s. or 35s. was charged for pasture attached

to the arable land. In the straths, and on the western and northern

coasts, rent was paid in accordance with the number of black cattle that

could be reared on the farm, and its amount per acre could not, therefore,

be ascertained. Wadset leases at one time frequently extended over two

nineteens, but after the commencement of the present century, few of these

were given. The duration of leases between the proprietors and principal

tacksmen was generally nineteen or twenty-one years; and between tacksmen

and sub-tenants (but leases between these were rare) three, five, or seven

years. The implements in general use at the commencement of the present

century were of the most primitive description. The better-to-do farmers

and proprietors had begun to use the modern Scotch plough, which cost from

£3 to £4, 10s., but the small tenants still employ the old Scotch plough,

made of birch or alder, with a thin plate of hammered iron on the bottom

and land side of the head. "This plough," says Captain Henderson,

"exclusive of the ploughshare, and sock, and plates, costs from 5s. to

15s., and is often made by the tenant who uses it. In the parishes of

Assynt, Eddrachilles, Durness, and Tongue, and in other parts, the

caschrom, a sort of spade, was in general use, while the clumsy

old-fashioned home-made wooden harrows were worked by the smaller tenants

all over the county, only those farmers who had improved ploughs having

had harrows with iron teeth. On the larger farms there were a few of the

modern horse-carts, which cost then from £12 to £16, but among the smaller

tenants, the well-known old basket cart was still in general use. Its cost

was from 20s. to 25s. Fuel, manure and other commodities were also

sometimes conveyed in baskets attached to a clubber or saddle, on

horseback. Only one threshing mill is spoken of as being in the county (at

Mid-garty) in 1808, and very few even of the larger farmers could boast of

a winnowing machine.

Captain Henderson states, that "along the coast side of

Sutherland the more opulent farmers plough their land with a pair of

horses without a driver, and in some cases with four oxen abreast, with a

driver. The smaller tenants, both along the coast and in the interior of

the county, use four small garrons (horses) abreast in their

plough, or perhaps two small ponies and two cows, all abreast, with a

driver; and in cases where their lots are small, two of them join and

furnish two ponies each, and plough their land jointly, the one ' holding'

and the other 'driving.' These people have their land all in crooked

ridges, broad in the middle and narrow at each end, in the shape of an S

, and a green bank or cairn of stones between every two or three

ridges. The course of cropping pursued on the southeast coast was, as a

rule, first, pease or potatoes; second, here or big, manured with ware or

seaweed or farm yard dung; third, oats, and then pease, &c, again." Bere

and oats were grown alternately in the interior and western districts, the

former being as a rule sown in lazy beds with abundance of manure, which

secured from 10 to 14 returns. Oats and rye were sometimes sown together,

generally on land in poor condition, and the mixed grain was manufactured

into a sort of coarse meal. A little wheat had been grown on the better

farms on the southeast coast, chiefly at Dunrobin and Skibo, and it is

said to have yielded from 8 to 10 bolls per acre; but Captain Henderson

states, that "owing to distance from markets, the variable climate, and

want of manure, the culture of it was given up." Bere gave from 4 to 7

bolls per acre, oats about 5 bolls, and pease from 5 to 6 bolls. During

the first ten years of the present century, turnips were on their

probation in Sutherland. Only a few small patches were grown by some

gentlemen farmers, but they stood their trial well, and soon increased in

popularity: the white and red top varieties were first sown. Potatoes

played a very important part in the economy of Sutherland in these olden

times. More than 1500 Scotch acres were planted with them every year, and

they formed a very large part of the food of the inhabitants. The yield

varied from 6 to 20 bolls per acre; and, in a favourable year, the quality

was excellent. Only on a few farms on the south-east coast were artificial

grasses sown, and these were clover and rye grass. The Argyle or West

Highland breed of cattle had been adopted at Dunrobin before the advent of

the present century; and so well did they thrive there, that in 1807 eight

milch cows were valued at £18 each, and the stots and heifers, from two to

five years old, at an average of £15 each. The general breed of cattle,

however, was the small black cattle of Skye and Assynt, "well shaped,

short legged, and hardy; the colour in general black, with some

exceptions." When mated with West Highland bulls these native cows

produced excellent stock, and Youatt says that, though smaller than the

cattle of Caithness, these black cattle of Sutherland were "far more

valuable, requiring only to be crossed by those from Argyle or Skye to be

equal to any that the northern Highlands can produce." Captain Henderson

states that the four year old stots at Dunrobin farm weighted from 5 to 6

cwts. in the carcass, and the cattle of the country tenants from 240 to

400 lbs. avoirdupois.

Up to the winter of 1806-7, when they nearly all died

of rot and scab, the old Kerry breed of sheep was almost the only variety

of the fleecy tribe in the county. A few blackfaced sheep had been

introduced before then, but, until the disastrous winter referred to, the

ancient breed maintained its sway. The Kerry sheep were " small with good

wool, some horned, others polled, some black, but the greater number

white, and some of grey colour." They weighed from 28 to 36 lbs. in the

carcass, and "the wool of from nine to twelve of them made a stone of 24

lbs." The introduction of Cheviot sheep, which began in 1806, will be

referred to afterwards. Goats were kept in great numbers then, but, like

the Kerry sheep, they were almost annihilated with scab and rot in the

spring of 1807. The most general breed of horses was the native garrons—a

thick low-set hardy breed, at one time reared all over the northern

counties. They cost from four to ten guineas, were from 44 to 52 inches

high, and were black, brown, or grey in colour.

The social habits of the inhabitants were, in these

days, very primitive. Their food and mode of living are thus described by

Captain Henderson—"The inhabitants near the coast side live principally

upon fish, potatoes, milk, and oat or barley cakes. Those in the interior

or more highland part feed upon mutton, butter, cheese, milk, cream, with

oat or barley cakes during the summer months. They live well and are

indolent; of course are robust and healthy. In winter the more opulent

subsist upon potatoes, beef, mutton, and milk; but the poorer class live

upon potatoes and milk, and at times a little oat or barley cakes. In

times of scarcity,—in summer they bleed their cattle, and after dividing

it into square cakes they boil it, and eat it with milk or whey instead of

bread."

The real condition of those small tenants, who up to

1820 cultivated the glens or straths of Sutherland, is a matter of much

interest in connection with the agricultural history of the county and

therefore an extract on the subject from Mr Loch's work may not be out of

place. He states—that "when that hardy but not industrious race of people

spread over the county they took the advantage of every spot which could

be cultivated, and which could with any chance of success be applied to

raising a precarious crop of inferior oats, of which they baked their

cakes, and of bere, from which they distilled their whisky; added but

little to the industry, and contributed nothing to the wealth of the

empire. Impatient of regular and constant work, all heavy labour was

abandoned to the women, who were employed occasionally even in dragging

the harrow to cover in the seed. To build their hut or get in their peats

for fuel, or to perform any other occasional labour of the kind, the men

were ever ready to assist, but the great proportion of their time, when

not in the pursuit of game or of illegal distillation, was spent in

indolence and sloth. Their huts were of the most miserable description;

they were built of turf dug from the most valuable portions of the

mountain side. Their roof consisted of the same material, which was

supported upon a wooden frame, constructed of crooked timber taken from

the natural woods belonging to the proprietor, and of moss-fir dug from

the peat bogs. The situation they selected was uniformly on the edge of

the cultivated land and of the mountain pastures. They were placed

lengthways and sloping with the declination of the hill. This position was

chosen in order that all the filth might flow from the habitation without

further exertion upon the part of the owner. Under the same roof, and

entering at. the same door, were kept all the domestic animals belonging

to the establishment. The upper portion of the hut was appropriated to the

use of the family. In the centre of this upper division was placed the

fire, the smoke from which was made to circulate throughout the whole hut

for the purpose of conveying heat into its furthest extremities,—the

effect being to cover everything with a black glossy soot, and to produce

the most evident injury to the appearance and eyesight of those most

exposed to it's influence. The floor was the bare earth, except near the

fire-place, where it was rudely paved with rough stones. It was never

levelled with much care, and it soon wore into every sort of inequality

according to the hardness of the respective soils of which it was

composed. Every hollow formed a receptacle for whatever fluid happened to

fall near it, where it remained until absorbed by the earth. It was

impossible that it should ever be swept, and when the accumulation of

filth rendered the place uninhabitable another hut was erected in the

vicinity of the old one. The old rafters were used in the construction of

the new cottage, and that which was abandoned formed a valuable collection

of manure for the next crop. The introduction of the potato in the first

instance proved no blessing to Sutherland, but only increased the state of

wretchedness, inasmuch as its cultivation required less labour, and it was

the means of supporting a denser population. The cultivation of this root

was eagerly adopted; but being planted in places where man never would

have fixed his habitation but for the adventitious circumstances already

mentioned, this delicate vegetable was of course exposed to the inclemency

of a climate for which it was not suited, and fell a more ready and

frequent victim to the mildews and the early frosts of the mountains,

which frequently occur in August, than did the oats and bere. This was

particularly the case along the course of the rivers, near which it was

generally planted on account of the superior depth of soil. The failure of

such a crop brought accumulated evils upon the poor people in a year of

scarcity, and also made such calamities more frequent; for, in the same

proportion as it gave sustenance to a larger number of inhabitants when

the crop was good, so did it dash into misery in years when it failed a

larger number of helpless and suffering objects. As often as this

melancholy state of matters arose, and upon an average it occurred every

third or fourth year to a greater or less degree, the starving population

of the estate became necessarily dependent for their support on the bounty

of the landlord.....The cattle which they reared on the mountains, and

from the sale of which they depended for the payment of their rents, were

of the poorest description. During summer they procured a scanty

sustenance with much toil and labour by roaming over the mountains; while

in winter they died in numbers for the want of support, notwithstanding a

practice which was universally adopted of killing every second calf on

account of the want of winter keep. To such an extent did this calamity at

times amount, that in the spring of 1807 there died in the parish of

Kildonan alone 200 cows, 500 head of cattle, and more than 200 small

horses."

The removal of these small tenants has already been

briefly referred to, and it will now suffice under this head to say that

the improved system of sheep-farming, which dates in Sutherland from 1806,

had by 1825 spread over the whole county, including the straths formerly

occupied by the small tenants; that by the latter date an improved system

of husbandry had been introduced on the arable farms, and that a spirit of

advancement had sprung up among all classes of the inhabitants, which has

raised the county into its present highly creditable position in regard to

both arable and pastoral farming.

The Progress of the Past Seventy Years.

Having perused the foregoing somewhat disconnected

notes regarding the social and agricultural condition of the county about

the advent of the present century, the reader will be the better prepared

for a brief account of the progress that has been made since the spirit of

improvement first took practical form in the county. This important event

may be credited to 1806, in which year the modern system of sheep-farming,

which has gained so wide a reputation for the county, was founded in

Sutherland by Messrs. Atkinson and N. Marshall, from Northumberland, who,

in that year, took an extensive sheep-walk from the Marquis of Stafford

near Lairg, and stocked it with Cheviot sheep. The development of the

sheep-farming will be more fully dealt with afterwards. Here it will

suffice to indicate very briefly the rapidity of its growth and the

enormous dimensions it has now reached. The county was found admirably

adapted to the Cheviot sheep, and they fast drove out the Kerry and

Blackfaced breeds. In 1811 they numbered about 15,000, while during the

next nine years they increased to no fewer than 118,400. The next decade

added about 38,000, and between 1831 and 1857 the number rose to about

200,000; while, since the latter year, they have exceeded that by from

16,000 to 40,000. It will thus be seen that during the first thirty years

of the present century the occupation of the straths and mountains of

Sutherland was completely revolutionized, and that the industry which has

in later days so highly distinguished that remote part of the United

Kingdom had, in little more than the short period mentioned, attained, so

to speak, almost to its full manhood.

While the first thirty years of the present century

wrought a great change in the interior of the county, that period also

brought about considerable improvement in the districts in which arable

farming prevailed. Captain Henderson states that, during the years between

1807 and 1811, "a general reform had begun in the management of land on

the eastern coast of the county and that several farms were getting under

the most approved rotation, in so far as the occupiers (intelligent

farmers from Morayshire) believed the soil and local situation would admit

of it; and perhaps better farm offices are not to be found in Scotland "

than on some Sutherland farms. The reform thus spoken of spread gradually

through all the arable districts of the county, wiping out all relics of

the darker ages, such as wooden ploughs, basket-carts, primitive systems

of rotation, and feal houses, and introducing in their stead an order of

things entirely new. Better attention was bestowed on the rearing of

cattle, and the stock of cattle, as well as that of horses and sheep, was

very greatly improved. Fields were squared, fences erected, new houses

built, service or local roads made, and other improvements effected, so

that by 1830 the face of the country had become wonderfully changed. The

late Mr Patrick Sellar, who visited Sutherland along with other Morayshire

men in 1809, and found it entirely devoid of roads, harbours, farm

steadings (excepting one or two), or any other signs of modern

agriculture, wrote as follows, in 1820, to Mr James Loch, commissioner on

the Sutherland property:—"At this time (1809) nothing could have led me to

believe that in the short space of ten years I should see, in such a

country, roads made in every direction; the mail coach daily driving

through it, new harbours built, in one of which upwards of twenty vessels

have been repeatedly seen at one time taking in cargoes for exportation,

coal and salt and lime and brick-works established, farm steadings

everywhere built, fields laid off and substantially enclosed, capital

horses employed, with south country implements of husbandry, made in

Sutherland, tilling the ground, secundum artem, for turnips, wheat,

and artificial grasses; an export of fish, wool, and mutton to the extent

of £70,000 a year; the women dressed out from Manchester, Glasgow, and

Paisley; the English language made the language of the county; and a

baker, a carpenter, a blacksmith, mason, shoemaker, &c, to be had as

readily and nearly as cheap, too, as in other counties." About 1809 Mr

Sellar entered on a lease of the farm of Culmaily, in the valley of

Golspie, and about a mile from that town, at a rent of 25s. per acre, with

an advance at 6½ per cent. of £1500 to assist in improvements, the extent

of the farm being 300 Scotch acres. This enterprising gentleman at once

set to work, and in a few years had the whole of the farm reclaimed, a

considerable portion of it from moor and moss and rough pasture,—had

erected upon it an excellent dwelling-house, farm steading, and thrashing

mill,—and had it brought to a high state of cultivation. He also took on

lease the adjoining farm of Morvich, and between the two he had reclaimed

over 250 acres before 1820. On the neighbouring farms of Kirkton, Drumroy,

and Dunrobin Mains, and at Crakaig and Skelbo, similar improvements were

executed about the same time; while at different parts along the

south-eastern coast smaller reclamations and improvements were carried

out, partly by the tenants and partly by the proprietors.

The want of reliable statistics makes it impossible to

give even an approximate idea of the number of acres of land reclaimed in

the county during any given period of the first half of the present

century. It has already been stated that in 1808 the arable area was

estimated at 14,500 Scotch acres, or about 18,125 imperial acres, but,

through the removal of the small tenants from the straths in the interior

during the second decade of the present century, and the turning of their

crofts into sheep pasture, that area must have been reduced by a few

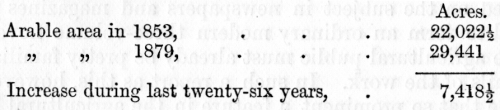

thousand acres—the exact extent cannot be ascertained. The first properly

organised inquiry into the agricultural statistics of Sutherland was made

in July 1853 by the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland at the

desire of the Board of Trade. According to that inquiry the arable area in

1853 was 22,022½ acres, or only 3,897½ acres more than in 1808—not a very

large increase for a period of forty-five years. It must be remembered,

however, that the statistics of 1808 were more roughly gathered than those

of 1853, and that, as already stated, the removal of small tenants and the

introduction of sheep-farming threw a large extent of arable land out of

cultivation. The following table shows the addition that has been made to

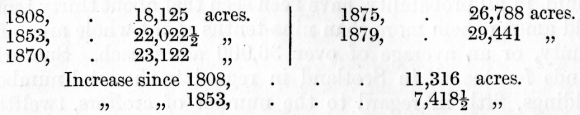

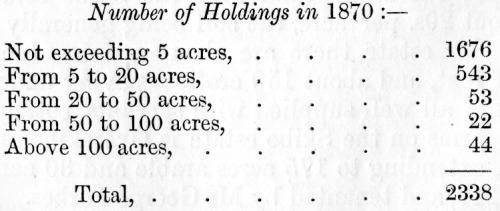

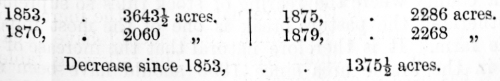

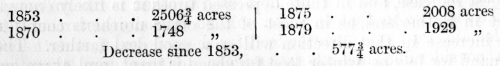

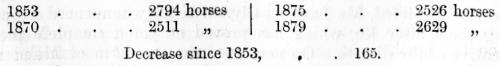

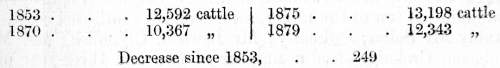

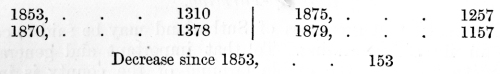

the arable area of the county during the past twenty-six years: —

As shall be afterwards shown, a large portion of this

increase has been effected by the Duke of Sutherland, within the last few

years, at Lairg and at Kinbrace; while the main part of the remainder has

been made up by the reclamation of pieces of land, varying in extent from

50 to 200 acres, on sheep farms throughout the county for the purpose of

producing winter food for the sheep. As a rule these latter reclamations

have been executed by His Grace, the tenants paying interest on the

outlay.

The progress of the present century is better indicated

in the valuation of the county than in its arable area. The valued rent of

the county in 1802, as entered in the Records of the Exchequer at

Edinburgh, was £26,193, 9s. 7d. Scots, or about £2,182, 15s. 9d. sterling;

while in 1808 Captain Henderson estimated the real rent of the county at

£16,216, 12s. 6d., including about £1750 for fishings and kelp, and about

£200 for houses in the burgh of Dornoch. The following table shows the

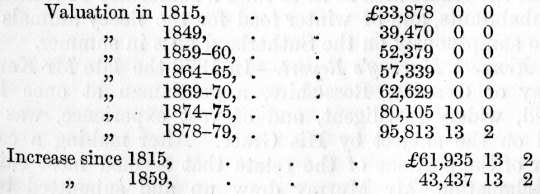

valuation at various times since the commencement of the present century:—

These figures bear indelible testimony to the. great

skill and enterprise that have been displayed during the present century

by the proprietors and tenants of Sutherland. There is but a small portion

of the county suitable for arable farming, and therefore the increase in

its arable area has been less during the past fifty years than in the

other Highland counties, but its natural resources, such as they are, have

been developed in a manner, and to a degree not surpassed in the history

of any other county in the kingdom.

The Duke's Land Reclamations.

The Duke of Sutherland's land reclamations have perhaps

earned a wider reputation than any other agricultural operation ever

undertaken in any part of the world. Though commenced only nine years ago,

more matter has already been written and published on the subject in

newspapers and magazines than is required to form an ordinary modern

three-volume novel; and thus the agricultural public must already be

pretty familiar with the details of the work. In such a report as this,

however, it is desirable that so prominent a feature in the agricultural

history of the county should receive due attention.

The Reasons that led to the Reclamations.—The

reasons that led the Duke of Sutherland to contemplate these reclamations

may first be noticed. As may be inferred from the great disproportion

between its arable and grazing areas, the county of Sutherland, the bulk

of which, as has been shown, belongs to His Grace, is, in the matter of

food, far from self-supporting. The consumption of oatmeal exceeds the

home production; and, as the mountains and straths of the county carry a

greater number of sheep in summer than these, aided by the available

production of the arable districts, can sustain in the winter season, a

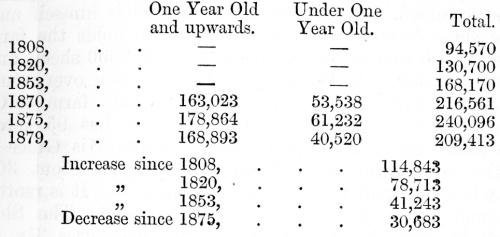

large portion of its sheep stock has to seek winter food beyond its