|

By John Macdiarmid, Highland

and Agricultural Society's Office.

[Premium—The Medium Gold Medal.]

Having been instructed by

the Directors of the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland to

proceed to St Kilda in H.M.S. "Flirt," ordered by the Government to convey

to the island provisions, seed, &c, for the inhabitants,—supplied partly

from the donation of £100 given by the Austrian Government in return for

kindness and hospitality shown to a few of its subjects who were

shipwrecked on the island last winter, and which was intrusted to the

Society for distribution—and partly from a fund held by the Society for

the benefit of the St Kildians,—I started for Greenock, where the "Flirt"

was stationed, on Monday the 7th of May, and got all the goods on board on

the following forenoon.

The whole of the goods were

procured for the Society by Mr David Cross, Argyll Street, Glasgow, whose

kindness and willingness in getting everything ready for despatch so

promptly, and on such short notice, shows the warm interest he takes in

the welfare of these remote islanders. Mr Cross on former similar

occasions undertook the same duty.

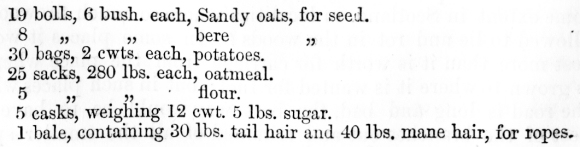

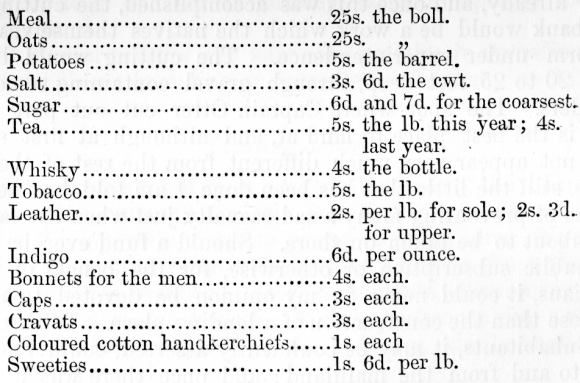

The supplies, of which the

following is a complete list, were conveyed from Glasgow, and taken

alongside the "Flirt" by a lighter supplied by Mr Steele, Glasgow:—

The "Flirt," commanded by

Lieut. O'Rorke, left Greenock about 10.30 on Tuesday evening, encountered

a very heavy sea and rather severe gale in rounding the Mull of Cantyre,

and on Wednesday could not proceed farther than Lowlander Bay, a small

inlet on the south-east coast of Jura, where anchor was dropped about 1.30

p.m., and where we remained till 6 a.m. on Thursday. On Thursday we went

to Tobermory, where we anchored for that night; made Portree on Friday,

and remained there over the night. Left Portree about 4 a.m. on Saturday,

and passed through the Sound of Harris about 1 p.m. Soon after, a good

stern breeze getting up, all sails were unfurled, and we were swiftly

wafted over the western main towards St Kilda, whose sharp outline could

be dimly discerned through a misty haze about 4 P.M. At 9.30 the rattle of

the anchor-chain over the bow proclaimed that we were really in St Kilda

Bay, and under the shadow of the towering cliffs of "Iort" (Gaelic name

for St Kilda).

The natives had sighted us

a long way off, and were afraid we were to pass. They lined the shore as

we arrived, and a boat manned by four active young St Kilda men was soon

alongside, and in a twinkling landed us safely on the rocky shore, where

we received the very hearty greetings and kindly blessings of these

simple-minded people. By this time the whole of the inhabitants had

appeared on the scene. A few words spoken in the vernacular conveyed and

spread the welcome intelligence that the supplies had come, upon which

there arose a great shout, or rather wail, of gladness and thankfulness,

the very dogs, of which there would be about a dozen, joining in the

refrain, and, combined with the hollow murmuring sound of the Atlantic

waves, made a weird din that sounded strange in our ears, and the memory

of which will not soon be effaced. The exuberant joy having somewhat

subsided, and a kind of order restored,—the weather being fine, and

knowing how unsafe and uncertain the anchorage was,—we proposed to land

the goods at once, and asked the natives to give us assistance with their

boats. But here came a hitch in the proceedings: the old men shook their

heads and gathered around their minister in solemn conclave; the minister

thrust his hands deep into his trouser pockets, and cast his eyes upon the

ground in pensive meditation; eager, anxious women and amazed children

stood with bated breath awaiting the result of the deliberation. An answer

was given, that as it was now drawing near the Sunday, and as the people

must be prepared for the devotions of the morrow, they could not think of

encroaching on the Sabbath by working at the landing of the goods. This

ultimatum was like the laws of the Medes and Persians, for no entreaty,

expostulation, or persuasive language on our part, though uttered in the

hardest Gaelic, would make them alter their decision; and as for reasoning

with them upon its being a work of necessity, such a conception seemed to

have no place in their creed. They told us that rather than land the goods

on Sunday they would prefer sending to Harris for them, should we be

compelled by stress of weather to betake ourselves there before Monday.

The captain endeavoured to land a few bags with the "Flirt's" boats, but

was completely baffled on account of the surf. The boats were not strong

enough to withstand the force with which they would be pitched on to the

rocks. The attempt had to be abandoned; and as nothing more could now be

done, on the minister's recommendation we resigned ourselves to

Providence, and waited patiently for Monday's dawn, trusting the weather

might be propitious.

Happily the weather

remained favourable, and all Sunday the ship lay as still as if in harbour.

I made myself the guest of the minister on Saturday night.

There were three services

on Sunday—at 11 a.m., 2 and 6 p.m. conducted in the same form as in other

Free Churches. Attended the forenoon service, along with several of the

ship's officers, and counted 66 of the natives present—21 men, 35 women,

and 10 children. At the close of the service the men all sat down and

allowed the women to depart first. All were decently and rather cleanly

clad. The men wore jackets and vests of their own making, mostly of blue

colour, woollen shirts, a few had linen collars, and the remainder cravats

around their necks, the prevailing head-dress being a broad blue bonnet.

The women's dresses were mostly all home-made, of finely spun wool, dyed a

kind of blue and brown mixture, and looked not unlike common wincey. Every

female wore a tartan plaid or large shawl over her head and shoulders,

fastened in front by an antiquated-looking brooch, and upwards of twenty

of these plaids were of the Rob Roy pattern, all got from the mainland.

Several of the women wore the common white muslin cap or mutch, and only

one single solitary bonnet, of a rather romantic shape, could there be

descried, adorning the head of by no means the fairest-looking female

present. All the men, and a few of the women, wore shoes; the rest of the

women had stockings on, or went barefooted. They seemed very earnest and

attentive to the discourse, and now and then heaved a long deep sigh, as

if by way of response. The singing baffles description. Everybody sang at

the top of his voice, and to his own tune, there being no attempt at

harmony.

Our coming had been

anxiously expected, and many a weary look cast across the sea towards

Harris, for two or three weeks preceding our arrival. At last the people

began to despair, and on the Monday before we arrived three of the

stoutest and hardiest men on the island set out in an open boat for the

Long Island in search of seed and meal, but, owing to contrary winds, were

forced back to their home on Wednesday night in a tired, worn-out

condition, having unsuccessfully combated the winds and waves for three

days, and at the risk of their lives.

Condition of the People

during Last Winter.

When the factor, Mr

M'Kenzie, with MacLeod's vessel, did not put in an appearance in autumn

last year, as usual, the inhabitants at once began to make preparations

for the winter's store. Last harvest was very bad with them, and they knew

they would be short of meal; and from the first they began to husband that

commodity. They also killed a number of the proprietor's sheep on the

island of Soa, and salted the carcasses for their own use during winter.

Whether they are expected to pay for these sheep I cannot say. The

Austrians, nine in number, were wrecked on the island between the 15th and

20th of January, and were at once quartered on the inhabitants, each house

taking a man or two by turns for a few days. The minister boarded three of

them for the whole time, which was between five and six weeks. Such a

sudden and unexpected influx to the population soon began to tell on the

already not over-abundant stock of meal, and part of the corn that was

reckoned upon for the spring seed had to be used for meal. Upon H.M.S.

"Jackal's" arrival to take off the Austrians, about the latter end of

February, the captain, hearing of the low state of their meal-barrels,

sent them ashore a quantity of biscuits and the best part of a sack of

meal. They speak of the Austrians as being very grateful, and content with

the humblest fare; very peaceable, and anxious and willing to assist and

help them in everything. From the time the Austrians left until the

arrival of MacLeod's vessel in April was the period of greatest hardship,

and they had to go for a week or or two without their porridge, although

they had, I think, plenty of salted meat. They say they could not afford

to make any bread, that their chief sustenance consisted of brew made from

the flesh of the fulmar—a sea-fowl which they catch in large numbers—mixed

with a handful of oatmeal. There was little or no milk to be had, none of

the cows having calved. MacLeod's vessel brought them 16 bolls of

seed-oats, 38 bolls of meal, and 20 barrels of potatoes. A good part of

their land remained unsown (about one-third), and several patches remained

unturned, as they preferred leaving it in that state until the supplies

arrived, when they would know if there would be sufficient seed for all

the land, besides food to serve them until autumn.

Judging from outward

appearance, I cannot believe the St Kildians suffered much from want of

food. They are, on the whole, full-faced, fresh-looking, and some of them

well-coloured and quite rosy. Several of the women are, in my opinion,

more than ordinarily stout. No doubt they might be wanting in farinaceous

food, and had to take more than was good for them of cured meat, which may

account for some of the complaints found under "Medical Report." It may be

mentioned that at this moment there are twenty carcasses of good cured

mutton lying in the storehouse in two barrels for the proprietor. These

were killed for him from his own flock in the island of Soa. There can be

no doubt, had the St Kildians been in great want they would have used this

mutton, and been made quite welcome to it by MacLeod. Of course, since the

arrival of the sea-fowl in March, they have had plenty of eggs. Salt fish

was very scarce with them last winter; they say the fishing season was

very stormy, that they could not go out, and that on one occasion they

lost the most of their lines.

The ordinary diet of a St

Kildian consists of—

Breakfast—Porridge and

milk.

Dinner—Potatoes, and the flesh of the fulmar, or mutton, and occasionally

fish.

Supper—Porridge, when they have plenty meal.

They take tea once or twice

a-week, and expressed themselves as rather fond of it. They seemed

surprised at the small quantity of tea sent in proportion to the amount of

sugar, and there was no evidence of the partiality for sugar and sweets

which has been attributed to them. Tobacco was what they invariably asked

for, and among the first questions put by the minister was, if I had

brought any tobacco, and when I had unfortunately to answer in the

negative, I perceived he felt far from happy.

Statistics of the

Population, &c.

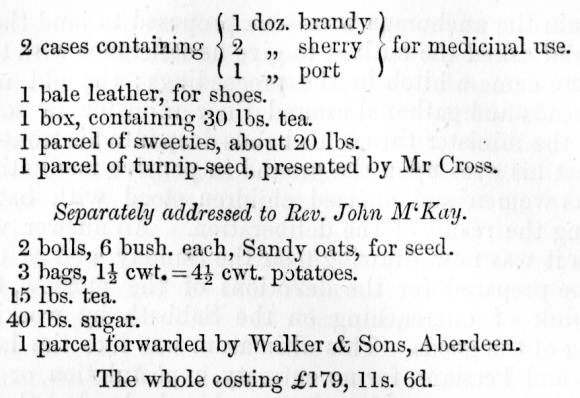

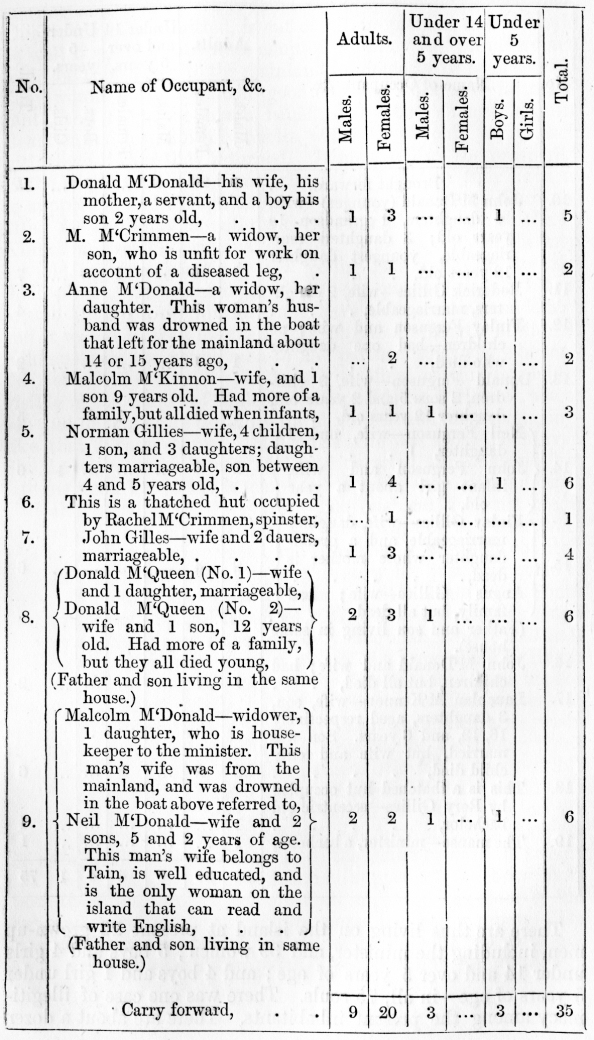

There are 18 inhabited

houses on the island—16 zinc-roofed cottages, and 2 thatched huts—arranged

in the form of a crescent, about 15 or 20 yards apart. They have been

numbered from right to left.

There are thus living on

the island at present 22 grown-up men, including the minister, and 39

women; 5 boys and 4 girls under 14 and over 5 years of age; and 4 boys and

1 girl under 5 years of age—in all, 75 souls. There was one case of

illegitimacy among the present inhabitants. There are about a dozen

marriageable women, while there are only two unmarried men. This it must

be admitted, is out of all proportion, and it would be well if some means

were adopted whereby the young women could be transferred to the mainland

for domestic or farm service. They would no doubt make good out-door

workers or farm servants, and might be much benefited by the change,

acquire cleanlier and less slovenly habits, which they would carry back

with them if ever they returned. It must tell on the prosperity of the

island such a large majority being females: they have to be supported, and

though able and willing workers, still are unfitted for the arduous and

dangerous pursuit from which the St Kildian derives his principal support.

The majority of the men are old, and comparatively few young lads are

ready to take their places. Intermarriages where the people are all

blood-related must prove injurious, and have a debilitating tendency; and

it would be well for the future physical strength of the St Kildians were

the young men to find partners somewhere beyond their own little colony.

The beneficial effect of this is plainly visible in the family of Malcolm

M'Donald (No. 9 House), whose son and daughter are certainly the shrewdest

and most managing-like that I came across. Malcolm's wife was from

Lochinver. She, however, proved unfaithful, and deserted her husband, but

fate overtook her in her attempt to reach the mainland, and it is said she

found a watery grave. The husband does not credit this report, but

believes that the occupants of the boat were picked up by a passing vessel

and conveyed to a foreign country. A curious incident bearing upon this

story has just now come to light. A young man said to belong to St Kilda

died in South Africa, and left a small legacy of £37, which amount has

found its way to the alleged father of the young man, who is still hale

and hearty. Meantime another man of the same name in Harris has laid claim

to the money, and maintains that it was his son who died in South Africa.

A letter relative to the matter was sent to Mr M'Kay, per the "Flirt,"

from a minister in Harris, wishing the matter explained to the possessor

of the money; and from what information could be gathered, the affair may

possibly find its way into the law-courts. M'Donald's wife could talk

English pretty well, and always acted as interpreter on the arrival of any

strangers. She had the honour of entertaining the late Duke of Athole when

he visited the island upwards of twenty years ago. It is said this

nobleman supped of the brew made from the fulmar's meat, and slept all

night on the floor of the hut, and vowed in the morning he never had

better repose. The duke is still remembered by the older people with

pleasure, and the hut that sheltered him pointed out with a feeling of

pride.

State of the Dwelling-Houses

and other Buildings.

The sixteen stone-and-lirne-built

cottages were erected about fourteen years ago, and are certainly much

superior to the habitations of the same class of tenants anywhere in the

Western Isles. The walls are well built, with hewn stones in the corners,

and are about 7 or 8 feet high; chimney on each gable; roof covered with

zinc (perhaps rather flat); outside of walls well pointed over with

cement, and seem none the worse as yet of the many wild wintry blasts they

have withstood. Every house has two windows, nine panes of glass in each,

one window on each side of door; good, well-fitting door, with lock. The

interior of each house is divided into two apartments by a wooden

partition, and in some a bed-closet is opposite the entrance-door. Every

house I entered contained a fair assortment of domestic utensils and

furniture—kitchen-dresser, with plates, bowls, &c, pots, kettles, pans,

&c, wooden beds, chairs, seats, tables, tin lamps, &c., &c. There is a

fireplace and vent in each end of the house, which is certainly an

improvement on the majority of Highland cottars' dwellings, where the fire

is often on the middle of the floor, and the smoke finds egress by the

door or apertures in the wall, or it may be by a hole in the roof. The old

dwelling-houses are also still kept in good repair and well thatched, and

in them the cattle are housed during winter. The minister's house is neat

and commodious, and is enclosed on one side by a very high wall for

shelter. It is a one-storeyed building, of four apartments and a porch. In

front of it is an enclosed bit of tilled land, in which some rhubarb was

growing, and in which was also set a rain-gauge. Immediately behind the

manse is the church—a good, substantial edifice, with four windows, and a

door. The minister can enter the church by a small door on the end next

his house, and which opens on a landing beside the pulpit. It has a slated

roof, but no flooring; and the seats consist of plain deal benches. Two

enclosed pews flank the pulpit —one for the elders, the other reserved for

visitors; and there is the usual box for the precentor. A good storehouse

is erected on the island, close to the landing-place. It is stone-and-lime

built, and has a slated roof. This house must be very useful, and in it

our supplies were to be put for division. There is another very good

house, something similar in shape to the manse. It was unoccupied, and in

it Mr M'Kenzie, the factor, resides during his stay when collecting the

rents.

Education. All read the

Gaelic Bible, of which there are several copies in every house. I was told

there are one or two persons on the island who can repeat the whole of the

Psalms from memory.

There is very little

literature besides the Bible—only a few Gaelic tracts. The minister has

several volumes, among which were the following: Smith's Moral Sentiments,

Butler's Fifteen Sermons, Hervey's Meditations, Works of John Owen, D.D.,

Select Works of Dr Chalmers, Baxter's Call, Sir John Herschell's

Astronomy. They all have a pretty fair idea of numbers and dates in

Gaelic, and know the value of the current coins; but it cannot be said

that there exists among them any great desire for money, and on offering

some to the children they did not clutch at it, as children elsewhere

invariably do, which may be accounted for by there being no shop where the

ha'pence might be converted into something more enjoyable. There are two

watches and one clock on the island. The people are fond of asking the

time, and upon showing them a watch they could tell the time at once. They

are anxious, and desire very much to be educated in English and

arithmetic, and many earnestly beseeched that a schoolmaster might be sent

to them. It is my opinion they would learn English very soon—the grown-up

people as well as the young. They are very sharp and quick at picking up

English names and words, and their keen, bright eyes bespeak an intellect

easily susceptible of impression. Why should not a representation be made

to the Highlands and Islands Committees of the Churches to give their

attention to the matter, and get the St Kildians taught, at least, the

simplest rudiments! Since my return I have been kindly informed by a rev.

gentleman that the Ladies' Association, of which Miss Abercrombie, 7 Doune

Terrace, Edinburgh, is secretary, do much for Highland education, and that

an application to them might be favourably considered. Surely the expense

would not be very great; and if a man could not be obtained willing to

spend three or four months on the island, the minister should be requested

to do the duty. Indeed, it cannot be conceived that anything could be a

greater pleasure to the minister than to train up the dozen lambs of his

flock in the knowledge of the English tongue and the simplest rules of

arithmetic, and an acquaintance with their own situation in respect to

their country, &c. Primarily, I believe, the duty of sending a teacher to

St Kilda lies with the School Board of Harris.

The minister, Mr John M'Kay

(a native of Lochalsh, Ross-shire), is an unmarried man, between fifty and

sixty years of age, of kindly disposition, fair intelligence, but far from

robust-looking, and apparently rather deficient in vigour and action. I

was informed that he was a long time schoolmaster at Garve, three years a

probationer at Kinlochewe, five years in South Uist, some time in the

island of Eig, and that from Eig he went to St Kilda, where he has been

now for about eleven years. He must have much spare time, which would be

profitably employed in teaching English to the young. His allowance from

the Free Church is £80 per annum. Attached to the manse is about an acre

of tilled land, and he keeps a cow and a few head of sheep, for which, it

is to be presumed, he pays nothing. His predecessor—who is buried in the

little churchyard on the island— was a Mr MacLeod, a relation of The Right

Hon. Sir John M. MacLeod, K.C.S.I., the former proprietor.

Thrift of the Inhabitants.

The men are mostly all

tailors, shoemakers, and weavers; in every house there is a loom. Some of

the men, attracted by the pattern of our Ulster coat, began to handle and

examine it closely, when suddenly one of them, with a beaming countenance,

which plainly indicated that the intricate deftness of the textile fabric

had dawned upon him, exclaimed—"Dheanadh sin fhéin sud!" (we could

manufacture that ourselves). As before mentioned, they make all their own

clothing, and sell a good deal of blanketing and tweeds. The St Kilda

tweeds are a good deal sought after for suits. A number of their sheep are

blackish-brown, and when their wool is properly mixed with the white, it

gives the cloth a slight brownish tinge, which is the only colouring it

receives. In mostly every house there was to be seen a spinning-wheel, and

a large pot, in which they dye their yarn. Strange to say, it is the men

who make the women's dresses. The women are very expert at knitting.

Judging from the well-built walls surrounding their patches of land, the

men must be rather good masons. They have axes and hammers, and in one

house there was a large box of joiner's tools. They are rather scarce of

nails, which are always of use to them in the case of accidents to their

boats. They had excellent candles, made from the tallow of the sheep; and

suspended in the church were two chandeliers, each having three of these

magnificent luminaries.

Tillage and Pastoral

Operations, with a Description of the Stock.

About an acre and a-half,

or perhaps a little more, of tilled land is held by each family, the

greater part of which lies in strips between the houses and the sea, and

the rest in patches behind the houses between that and the foot of the

hills. The soil is a fine black loam resting on granite, and by continued

careful manuring and cleaning, looks quite like a garden. Yet with all

this fine fertile appearance, the return it gives is miserable; and this

can only be accounted for, I presume, from the land never being allowed

any rest under grass. The only crops grown are potatoes and oats, with a

little bere. Within the remembrance of some of the older men, the returns

were double, or nearly treble, of what they now are. Questioned several of

the men upon this point, and got exactly similar answers. From a barrel of

potatoes (about 2 cwt.), scarcely 3 barrels will be lifted. They require

to sow the oats very thick—at the rate of from 10 to 12 bushels to the

acre, and the return is never above two and a-half times the quantity of

seed sown; formerly it used to be five or six times. I was shown a sample

of the oats grown, but they were very small and thin, and thick in the

husk. If possible, they avoid sowing home-grown seed, as it never gives a

good return. Flails are the instruments used for separating the grain from

the straw. The ground is all turned over with the spade, of which they

have a number in very good order. The Cas Chrom (spade-plough), so common

in the Western Isles as an implement of tillage, was once in use, but has

long ago given place to the spade, and not one is now employed, The land

is harrowed with a sort of strong, roughly-made wooden hand-rake. They

have iron grapes for spreading their manure. The dungpits are situated

generally a few yards in front of the house, in the end of the patch of

land, sunk a few feet in the ground,—rather convenient for being conveyed

to the land, which is done by wooden creels or baskets. Saw no

wheelbarrows; but there were one or two handbarrows. They have sufficient

manure for their land. Sometimes they gather a little seaware for manure,

but there being no beach, it is not to be got in any great quantity. There

is a hand-grinding mill of the old Scotch pattern in every house. This

consists of two circular granite stones, about 15 or 18 inches in

diameter, laid flat upon each other. In the centre of the under one is an

iron pivot, upon which the upper one is turned by grasping a wooden

handle. The corn is allowed to drop into a hole in the centre of the upper

stone, finds its way between the stones as the upper is kept revolving,

and by the time it comes out at the edge between the stones it is supposed

to be sufficiently ground. The meal makes very fair porridge and bread.

The whole of the arable land is enclosed by a stone fence, and lies on a

gentle slope between the bay and the foot of the hills. Noticed one or two

small enclosures planted with cabbages—not this year's plants. Turnips

were once grown rather successfully, but of late years they have not

thriven. They may renew the experiment this season with the seed sent by

Mr Cross. The pasture-land is excellent, and forms as fine a sheep-run of

its size as can be seen anywhere. There are four hills or tops—Mullach

Skaill, Druim Geal, Mullach Onachail, and Mullach Oshivail. The highest—Mullach

Ona-chail—is 1220 feet in height. In going over the island, its grazing

extent may be estimated at about one and a-half times the size of Arthur

Seat and the Queen's Park, Edinburgh; it may be more or less, but, judging

from observation, that is about the most approximate illustration I can

give of its area. Nothing is to be seen growing naturally on the island

but grass, which is said to be very nutritious, and upon which the cattle

and sheep thrive remarkably well. In some parts last year's grass was

lying quite thick where it had not been eaten. Passing across Druim Geal,

one comes in at the top of Glen Mor, a lovely valley on the south-west

side of the island. A brook runs through it, and a landing can be effected

at the lower end of the glen, although the rocks look rather slippery.

This glen must look beautifully green in summer. It rises with a gentle

slope from the sea, and is pretty steep on one side towards Mullach

Onachail. There are very few rocks or stones cropping up on the surface,

and better pasturage for blackfaced sheep and Highland cattle could not be

desired. The surface is yet in its original state, and quite different in

appearance from the side of the hills next the cottages, where the soft

green carpet is so sadly deteriorated for grazing purposes by being so

lamentably hacked up for fuel.

Counted 1 bull, 21 cows,

and 27 young cattle on the island, all in wonderfully good condition—much

better, in fact, than in many places on the mainland in this trying

season. The bull, brindled in colour, is of the West Highland breed, about

eight or nine years old, and by no means a bad animal. He was brought from

Skye about five or six years ago, and has left a mark of improvement on

the young stock. The cows are of a degenerate Highland breed, light and

hardy-looking, and mostly all black in colour. The young cattle are

red-and-black in colour; healthy-looking, and among them are a few

well-shaped and well-coated animals, which on the mainland might fetch

about £5. The average value of the young cattle cannot be put above £3,

15s. a-head—that is, on the mainland. In autumn, 1875, they received from

Mr M'Kenzie, M'Leod's factor, from £2, 15s. to £3 for their young cattle—a

price unprecedented with them, and which was indeed as much as they would

be worth to any man intending to sell them on the mainland so as to pay

the cost of transit. Mr M'Kenzie, had he come last autumn, would have got

12 young cattle, which are still on the island, and which must be deducted

to arrive at the average number of cattle kept during the winter. There

are between 12 and 14 calves this season, nice, lively, well-fed little

beasts. It is reported that dealers from Harris have gone to St Kilda and

bought the young cattle as recently as three years ago, but this requires

confirmation. It was impossible to ascertain the number of sheep on the

island, for none of the men questioned seemed to have any accurate idea of

how many there might be, or if they had, perhaps they imagined it was the

best policy to keep it dark; however, from what was to be seen in

perambulating the hills, the number may be put down at over 400. There may

be many more, but I do not think the number is less than that. Each

family, it is said, should have between 20 and 40 sheep; but, on inquiry,

it was found that some families had scarcely any at all, while others

again had a good many more than the regulation number. The sheep are badly

managed, and receive very little: attention. In winter they are allowed to

shift for themselves, and a number are blown over the rocks in seeking

shelter from the storms. Their system of sheep rearing and management is

very much to be condemned. Any one having the least experience in

sheep-farming would suppose that the sheep would be all held in common,

and the wool and carcasses divided equally; but such is not the case:

every man has his own mark, and no two of the tenants have the same

number. The size of a man's flock depends very much upon how they thrive

and survive the winter's storm, and whether he gives them any attention.

The sheep are very wild; and though it was just after the lambing season,

appeared in very good condition, and able to climb the steepest parts of

the rocks. The yeld sheep are plucked about the beginning of June, and the

ewes about the middle of summer. They sell neither sheep nor wool. From 2

to 5 sheep are killed by each family for the winter's supply, and the wool

is made into blanketing and tweed, which they sell. They keep about 12

tups. Some blackfaced tups were brought from Skye about six or seven years

ago, from the same person who supplied the bull. The breed of sheep may be

called a cross between the old St Kilda breed and the blackfaced; but if

fresh tups were annually introduced, they would soon be all very good

blackfaced sheep. Nothing is applied to the sheep by way of smearing; and,

so far as could be ascertained, they were quite free from scab and other

skin-diseases common to the class. The St Kildian should be initiated in

the art of clipping his sheep, for plucking must be a sort of cruelty to

the animals. It is my opinion that the number of sheep might be much

increased were they all turned at once into one flock, the 16 families

having the same share in common, and two men appointed, whose sole duty

would be to look after the sheep. There should be a fixed rent for the

pasturage, and not, as at present, levied on each head of sheep. Then the

people would endeavour to get as much as possible out of the pasture, and

the landlord, may be, would be surer of his own also. The proprietor has

between 200 and 300 sheep on the island of Soa, and between 20 and 30 of

the native St Kilda breed on the island of the Dun. The latter I only saw

at a distance, and they appeared of a light-brown colour. All the tups

were on the Dun island, and there was not an opportunity of seeing them.

The sheep are said to be very fat in autumn when killed, which may well be

believed from the nature of the pasture; and the St Kilda mutton that was

presented to us for dinner would favourably compare in flavour and quality

with the best fed blackfaced. What is not used of the tallow for candles

they sell to the factor. They had no butter on the island, and make but

very little of that article of diet. Saw no vessel of the shape of a

churn, and omitted to ascertain their process of butter-making. Cheese is

more made, as it sells better, and in order, they say, to give it a better

flavour, they milk the ewes, and mix their milk with that of the cows.

There are a number of dogs on the island—in fact, too many for the number

of sheep, unless they use them for some other purpose, such perhaps as

catching the birds. They are collies of a kind,—certainly not pure

bred,—and did not by any means look as if they had suffered from

abstinence. In almost every house there was to be seen a cat, from which

it is to be inferred that mice exist also. There are only two hens on the

island. Within the recollection of several of the older men, a lot of

ponies were kept and reared, some of the crofters having as many as four

and five. I was told that upwards of thirty-five years ago a man of the

name of M'Donald took a lease of the island, and there being a good price

for ponies at that time, he, under the pretence that they were very

destructive to the grass, got them all shipped away, and there has been

none since. A pony or two might be useful in carrying home the fuel, &c.;

and I would certainly suggest that a Highland bull, and half a dozen

blackfaced tups, be sent to them. It would improve their stock immensely,

and as the young cattle are sold annually, the keeping up of the breed is

a very important matter. Such a price as they got in 1875 has opened their

eyes a little to the fact that the cattle deserve a a little more

attention; and it would be well to impress upon them that if they

succeeded in rearing one good beast every year, it would almost pay the

rent. Perhaps a few goats might find a living among the rocks, and as the

people are good cragsmen, they could have no difficulty in getting at

them. The skins might be of some value, and the carcass would serve for

food. There are neither hares nor rabbits on the island. It is the kind of

place where the latter might thrive, but I do not see that their

introduction could be recommended.

The weather in winter is

very wild and boisterous. Snow falls, they say, pretty heavily, and buries

the sheep sometimes; and the frost is occasionally severe.

Rents.

For each croft and house £2

is charged annually. The sheep are charged for at the rate of 9d. a head;

but there was no mention about the cattle being similarly taxed. The

present rents were fixed by Mr M'Raild, factor to the late proprietor; and

there has been no alteration since MacLeod of MacLeod came into

possession. I understand the present factor got over the books from Mr

M'Raild; and the same number of sheep that were then marked against each

tenant is what he pays for still. So far as could be ascertained, the

number has never been raised, nor reduced, nor counted by the present

factor; and it is quite possible that a man may be paying rent for 20

sheep when he has none at all, while another pays only for the same

number, though the number he has may be 50. A slight investigation in this

direction might have the effect perhaps of placing the whole of them, for

a time at least, on a more equitable footing. This part of the rent is

always paid in kind; and it is impossible to arrive at the actual value

given to the proprietor. None of the men keep an account of the quantity

of produce they give to the factor, and the amount of goods they take in

return. They have great confidence in Mr M'Kenzie, who, they say, is just

and generous, and easy to deal with, and always anxious to attend to their

wants in bringing from the mainland whatever they may order or stand most

in need of. I have heard it stated that between £70 and £80 is the annual

revenue derived by MacLeod from the island, for which he paid £3000 about

five years ago. They are never pressed for arrears; and, so far as could

be made out, they are contented with their lot, and consider that they are

very fairly dealt with. They are very much attached to their island home,

and there is no inclination to emigrate. Of their landlord, MacLeod, they

speak in the very best terms, and consider themselves very fortunate in

being under his guardianship; and not one single word or expression did I

hear uttered implying want of confidence or distrust in his dealings with

them. As one old woman put it in Gaelic, "It would be a black day for us

the day we severed ourselves from MacLeod's interest." The following was

communicated to me by Mr M'Kay:—"A gentleman who visited the island lately

wanted them to go to the mainland with their produce in their own boats,

and cease the barter system maintained with the proprietor. When MacLeod

heard of this, he expressed himself as well pleased with the proposal, and

informed them he would appoint a man to take their rents in money on the

mainland. At the same time, he warned them of the danger of trying the

experiment with such boats as they possessed. The discussion went on, the

gentleman stranger strongly recommending the change, while Mr M'Kay, the

minister, pointed out the danger and risk they would expose themselves to,

and warned the people of the doubtful result of dispensing with MacLeod's

assistance. A written document, or, as it were, a contract between MacLeod

and the people was sent to the island, calling upon all those who wished

to adhere to him and the present system to give in their names. Into this

contract or agreement Mr M'Kay got a clause inserted granting permission

to any of the inhabitants who wished it to go to the mainland whenever it

suited them, and buy and sell as pleased them. Upon this every man gave in

his adherence. This was the cause of a rupture between the gentleman

stranger and Mr M'Kay, and some hot words ensued." I give the above

verbatim, as it was related to me on the island; and it may be taken for

what it is worth. It is my opinion that, with their present boats, any

attempt to reach the mainland would prove as often unsuccessful as

otherwise. With a smack the difficulty might be overcome, and the danger

lessened; but before they could keep a smack, something would require to

be done to the landing-place, of which more anon. Perhaps it might not be

out of place to suggest the idea of having a shop established in St Kilda.

There is an educated woman on the island, the wife of Neil M'Donald (house

No. 9); and if she were to take charge of a kind of store, and a steamer

was to call twice a-year, something might be done in the way of trading.

Exports and Imports.

I quite failed in getting

any approximation to the quantity of exports. Had I been there on a week

day, I might have prevailed upon each to try and draw upon his memory and

give me a list of what he gave the factor every year; but most

unfortunately it was Sunday, and the people were extremely reticent. If

any questions were asked them, they would either move away or tell me

plainly they would not answer such inquiries on the Sabbath.

The feathers of the

sea-fowl appear to be the principal export, and from them the people

derive the greater part of their income. The price paid by the factor for

feathers is 6s. per stone of 24 lbs. for black feathers, and 5s. for grey

for which, upon inquiry, I find he might receive, by selling in Edinburgh

or Glasgow, from 7s. to 10s. the stone.

Tweeds and blanketing come

next. The quantity sold by each family varies from 12 to 80 yards. For the

tweed they receive 2s. 6d. per yard. Blanketing, plain, 2s. 3d.; with

blue-border, 2s. 4d. It is worthy of notice that Mr M'Kenzie buys the

cloth by what the people called the "big yard," which, upon being produced

and measured, was found to be 4 ft. 1 in. in length. They are able to sell

from 1 to 4 stones of cheese, for which they get 6s. 6d. per stone of 24

lbs. Several sell from 1 to 1½ stone of tallow, at from 7s to 8s. per

stone. Oil is also exported. It is obtained from the fulmar, which, when

caught, emits a small quantity of the liquid from his bill. This oil is

kept in the dried stomachs of the solan geese, and in every house could be

seen, strung up over the fireplace, several of these oil pouches. It is

much used for light by burning in their lamps, and for what they sell they

receive 1s. the Scotch pint, or about 2s. the imperial gallon. Ling, which

is the only fish caught, sells at 7d. each, the proprietor supplying the

salt free. It is doubtful if the fishing could be much extended or

prosecuted with any great degree of success under present circumstances,

as the entire absence of shelter everywhere round the coast, combined with

the danger of landing, should any sudden storm arise, prevent the people

from venturing very far out from the island, or remaining long at sea.

Unquestionably the finny tribe must here be found in great abundance, when

we consider the enormous quantity it will take to feed the innumerable

flocks of solan geese and other aquatic birds that frequent these rocks in

summer, and whose whole subsistence is derived from the ocean. I was

informed that the following prices were charged by the factor for the

different imports during the last two or three years:—

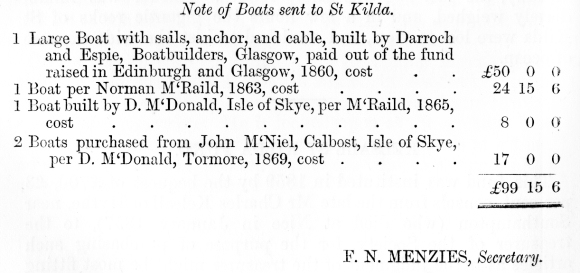

Boats and Landing-Place.

At present there are four

boats on the island. Two of them are almost new, and, though excellent

boats of their kind, are scarcely strong enough built to withstand long

the rough usage of having to be hauled over the rocks when landing. These

boats have been presented to the St Kildians by gentlemen who visited the

island. I believe that Government, on a representation by the captain of

the "Jackal" (Captain Digby), is sending them another boat this year; but

if like the boats carried generally by Government vessels, it will be of

very little use to them. The best plan would have been for the Government

to have ordered a boat to be built specially for them at Stornoway,

something after the style of the herring-boats common there. The want of a

proper landing-place is a great drawback to the island, and causes

incalculable toil and great danger to the inhabitants. No one who has not

visited St Kilda can form any idea of the great swell there is on the sea

even in the absence of the slightest breeze. Captain Otter of the Royal

Navy, who was for a long time stationed on the west coast, seems to have

taken a great interest in this question of a landing-place; and if his

proposed plan, which he had commenced, and which, had he been spared, he

intended to have completed, were carried out, it certainly would be the

greatest and best boon that could possibly be conferred on the

inhabitants. He intended to have cleared away the rock in front, and then

made a cutting into the bank to the right front of the minister's house

for about 40 or 50 yards, and let the sea run in at high water. This would

give them a safe landing-place and a sheltered harbour where a smack could

be moored all winter. The project would not, I think, be very expensive. A

good deal of the rock has been cut away already, and once this was

accomplished, the cutting in to the bank would be a work which the natives

themselves could perform under superintendence. The cutting would be, say

from 20 to 25 feet deep, through gravel containing some large boulders.

The spot where Captain Otter cut out part of the rock is the best place to

land at, and although at first sight it does not appear very much

different from the rest of the rocky shore, still the little that has been

done, I am told, has been the means of preventing many a sad casualty just

when the last step was about to be taken on shore. Should a fund ever be

raised, by public subscription or otherwise, for the benefit of the St

Kildians, it could never in my opinion be devoted to a better purpose than

the construction of a landing-place. With a smack the inhabitants, it may

be confidently asserted, could find their way to and from the mainland;

and once there was a proper and safe place for the anchorage of such a

vessel, there is no doubt it would soon be forthcoming. The people are, in

my opinion, fearless sailors.

Fuel.

This subject cannot be

approached without a feeling of keen regret and sorrow, as it concerns

more than anything else the future fitness of St Kilda as an abode for

man. What the result will be if the present disastrous system is allowed

to proceed is not for me to predict. A very large extent of their pasture

has already been bared by the turf having been used for fuel. Slow as the

process appears to be, yet with the lapse of time it will as surely work

out the dire effect, and render St Kilda quite uninhabitable either for

man or beast. In asking a woman who was piling dried grassy turf upon the

decaying embers of what was recently a similar pile, if she did not feel

sorry at reducing to ashes the best support of their cattle and sheep, she

replied, "Yes; but we must have our food cooked." At best it is but a poor

substitute for even peat, of which nothing worth mentioning was to be seen

on the whole island. All over the hillsides, and dotting the summits

almost as thick as haycocks in a hay-field, are the claits or small

buildings where the turf is stored away to dry during the frosts of

winter, and from which they carry it home on their backs as it may be

required. These claits take the attention of strangers at once when

approaching the island, and we were quite puzzled to comprehend their

purpose. They are oblong in shape, built of stone, with the walls

inclining inwards and covered on the top with turf, and the area which

they altogether cover must extend to a good few acres. All around are

scores, it might safely be said hundreds, of acres bared of what was once

the finest pasture. In some parts where a little soil was left to cover

the rock after the first cutting, a second coating or skin is forming—-a

poor apology for the original sward.

With such a ruinous yet

necessary practice in operation, it is almost needless advocating an

increase in the sheep stock.

Medical Report

Staff-Surgeon Scott, of

H.M.S."Flirt," hearing of the infirm state of Widow M'Crimmen's son, who

is suffering from disease of the bones of the leg, volunteered to go and

examine him. No sooner had the report spread that a doctor had come on

shore, than we were surrounded by about a score of patients, clamouring

for a cure for their various ailments. Mr Scott, after making a minute and

careful examination of all the sufferers, kindly handed me the following

report:—

"St Kilda, Medical

Notes.—The inhabitants are all of moderate stature (the men from 5 ft. 5

in. to 5 ft. 7½ in.), look healthy and well-fed; but closer inspection

shows the muscular development to be of rather a flabby character. The

ailment par excellence is rheumatism, as might be expected from the

exposed nature of their island home. This disease is common to both sexes,

and in a number is attended with pain in the cardiac region, with

irregular heart's action. Dyspepsia is also common; and it is noticeable

that the teeth were in general short and square, as if they had been filed

down. There were several cases of ear disease, and there is a tendency to

scrofula. One boy had disease of the bones of the leg. Their staple food

consists of oatmeal porridge and the flesh of the sea-fowl. Colds and

coughs are common enough, but no case of phthisis presented itself. We saw

only two cases of skin-disease (one of herpes and one of sycosis menti),

and these were trifling, for nature seemed to have endowed them with very

clean, smooth epidermic coverings. There is said to be great fatality

among children when from 7 to 14 days old, but why was not easy to make

out. We were told that the women sometimes proceeded to the mainland of

Harris to be confined there and have medical attendance: whether such a

journey in a small open boat is at all beneficial for a woman in an

interesting situation, is at least open to doubt. The children whom we saw

were all healthy-looking. The medicines which would be of most use are

those for cough and rheumatism; and for the latter, strong liniments would

be the most appreciated."

It may be mentioned that Dr

Scott supplied a number with medicines, so far as his laboratory would

permit.

On inquiry, I was told that

some medicines are kept by the inhabitants, and that a small supply is

sent annually by the proprietor, such as castor-oil, senna-leaves, salts,

and some tonics. On one or two occasions they have had a call from medical

men, who prescribed and gave them medicines. The last death took place in

July 1876—a child 4 years of age. It is four years since an adult died—a

strong young man, 28 years of age. On that occasion, a kind of epidemic

must have visited the island, for about fifteen grown-up persons were

bedridden at the same time, and all dangerously ill.

Catching the Sea-Birds.

The expertness and daring

of the St Kildian in this his fond pursuit has been so much commented on

by persons who have visited the island, that I regret not having had an

opportunity of witnessing the natives engaged in this operation.

On conversing with them

upon their intrepidity in scaling and exploring the stupendous cliffs in

search of sea-fowl, I could perceive that there exists among the men a

great desire to excel as successful cragsmen. He is looked upon as the

greatest hero who succeeds in capturing the largest number of birds at a

time; and a young man was pointed out to me who, in a single night last

year, bagged six hundred.

Landing of the Goods.

On Sunday night I did not

retire to rest, and at one o'clock on Monday morning turned out the

natives. They were not slow in answering to the call, and immediately

launched two of their boats, and commenced the operation of bringing the

supplies ashore. The "Flirt" lay between two and three hundred yards out.

Her boats were not used for transporting the goods being too slim-built to

stand the strain of having to be hauled on to the rocks; and the

assistance rendered by the crew was lowering the bags, &c, into the

natives' boats. The whole of the work of landing devolved upon the St

Kildians themselves, who certainly laboured earnestly and willingly. The

most difficult part of the work was hauling in the boats, and at this the

women gave great assistance—pulling with all their might at a rope

attached to the prow of the boat. The men pushed at the stern and sides

with their shoulders, the surf at every swell surging up around their

legs.

A table for the division of

the goods was made out, and a copy of it left with Mr M'Kay—with an

explanation that although a stated quantity was put down for each family,

it was more for their guidance, and to give an approximation of the amount

each was likely to receive; but that they would require to exercise their

own discretion in giving where there was most need, as my time did not

permit to make an investigation into the different wants of each dwelling.

I have no doubt, from the

friendly relations that seemed to prevail among them all, that the whole

of the goods would be amicably and peaceably shared.

Although the seeds in my

table were equally divided, special instructions were given that those who

had the most land to sow should receive more than the others. The brandy,

wine, and sweeties were to be given out equally. The people themselves

were to arrange about the division of the leather and horsehair.

About half-past seven o'clock on Monday morning, the 14th of May, the last

bag was safely landed. Anchor was immediately weighed, and in a few hours

the gigantic rocks of St Kilda were lost to view, and vanished amidst the

wide expanse of ocean.

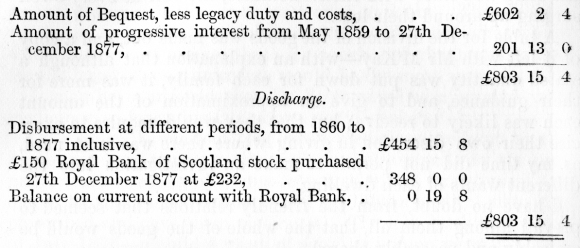

KELSALL ST KILDA FUND.

This fund was instituted in

1859 by the bequest of £700, £3. per cent. consols from the late Mr

Charles Kelsall of Hythe, near Southampton (who died at Nice in January

1857), to the treasurer of the Society, for the purpose of purchasing such

articles as in the judgment of the treasurer might be most fitting for the

inhabitants of the island of St Kilda. From the wording of the will, there

was some difficulty about deciding whether the treasurer of the Highland

and Agricultural Society was meant, but the Vice-Chancellor recognised the

validity of the Society's claim to the charge and application of the

legacy. After the necessary affidavits and powers of attorney had been

made and sustained, which occupied over a year, the stock was sold, and in

May 1859, Messrs Connell & Hope, the Society's London Agents, remitted the

proceeds, less the legacy duty and costs. The amount was lodged on deposit

receipt with the Royal Bank of Scotland, and the following is an abstract

of the treasurer's intromissions.

Charge

It should be added that in

1860 a subscription was raised in Glasgow and Edinburgh for the benefit of

the inhabitants of St Kilda, and that a large sum (above £600) was

expended on their behalf during the years 1860, 1861, 1862, and 1863; and

that the £100 received from the Austrian Government per the Lord Advocate

was laid out in supplies sent in 1877.

|