|

By James Macdonald,

"Scotsman" Reporter, Aberdeen.

[Premium—The Minor Gold Medal]

Introduction.—In America

the practice of agriculture, as presently carried on, is in the main as

primitive and simple as it was in Scotland two hundred years ago. The

means by which that simple work is executed are certainly far superior to

those at the command of our forefathers eight generations back. America is

ahead of all other countries in the world in labour-saving machinery; but

the practical every-day manipulation on an average American farm is as

elementary and simple as in Scotland at the period referred to. American

farmers plough, and sow, and reap, and heed neither the principles of

rotation nor the science of manuring. Their management of live stock, too,

is as simple as ever it has been in Scotland. And yet this new country

throws Scotland far into the shade by the efforts it has been making to

disseminate throughout its bounds scientific agricultural education. It

recognises that though so long as the soil retains its virgin richness,

farmers may thrive even by the primitive, simple system of farming that

now prevails, the day is not far distant when American agriculture, like

agriculture in Britain and in other-long settled countries, will demand

the aid of science; and so, looking beyond the actual wants of the time,

and discarding the maxim that sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof,

Americans (the inhabitants both of the United States and Canada) are

making a bold, liberal, and intelligent effort to train up a race of

farmers that may be able to grapple with the stubbornness of the soil when

it becomes weary of its present well-doing and refuses to yield profitably

without "priming." Undoubtedly such stubbornness will come some day. In an

old fully developed country, where every small grocery business seems as

safe to its heirs apparent as an entailed estate, few regard agriculture

as the essential basis of true national prosperity; but in America, whose

manufactures and commerce are still in process of formation, every one

feels that without a sure foundation in agriculture, these commercial

fabrics would be frailty itself. How true are those eloquent words of

Daniel Webster, the great American orator, "Agriculture feeds us; to a

great extent it clothes us; without it we could have no manufactures, we

could have no commerce. These all stand together, but stand like pillars

in a cluster, and the highest is agriculture."

Agricultural Colleges in

the United States.—By an Act of Congress, passed in 1862, a large free

grant of land (extending to 30,000 acres for each senator and

representative in Congress according to the census of 1860) was given to

each state for the "endowment, support, and maintenance of at least one

college, where the leading objects shall be, without including other

scientific and classical studies, and including military tactics, to teach

such branches of farming as are related to agriculture and the mechanical

arts." Two-thirds of the states have disposed of the whole of these

extensive land grants or land scrips; but still more than a million and a

half of acres belonging to the other third remain unsold. Already,

however, all of the thirty-eight states in the Union, with the exception

of Nevada, have established educational institutions in accordance with

the Act of 1862; while Georgia, besides the regular state college, has a

separate college of agriculture in the northern section of the state,

making in all in the United States thirty-eight institutions in which

scientific agriculture is taught as a prominent branch of their course of

study. During a recent lengthy tour throughout the continent of North

America, the writer made a point of inquiring into the working of these

industrial colleges, and was glad to find that they are diffusing a

healthy influence among the agricultural community of the country. Several

of the colleges have been established so recently that as yet they have

been able to effect but very little real substantial work, or to settle

down to any definite line of policy; but, on the other hand, the older and

better conducted institutions (of course they have not all been managed

equally well) have already done most valuable service to the country by

sending forth fleece after fleece of well-taught graduates. Each college

has from six to ten professors (besides assistants), including a professor

of prac-tical agriculture, and attached to each is an experimental or

model farm, on which the students of agriculture are taught the elements

of practical agriculture, and have to labour for so many hours per day,

and on which are conducted experiments on the principles of manuring and

rotation, and on the various kinds of farm crops. The course of study at

these institutions, especially as it relates to agriculture, is pretty

much alike; and an outline of the modus operandi at the Michigan College,

the oldest and one of the best in the country, may suffice to indicate

what the agricultural, or more properly speaking, the industrial colleges

of the United States really are, or aim at becoming.

Michigan Agricultural

College was opened in May 1857, and is situated on the Red Cedar River, in

the suburbs of Lansing, the state capital of Michigan. The college grounds

in all extend to 676 acres, of which 300 are under regular cultivation.

For four years the institution was under the management of the State.

Board of Education, but since 1861 it has been controlled by the State

Board of Agriculture formed for the management of the college. The Act of

1862 gave to this college 235,673 acres of land, of which a little over

72,000 acres have been sold, yielding $231,670 (£56,334), the interest of

which at seven per cent. is applied to the support of the college.

The whole college course

extends over four years; and candidates for admission must not be less

than fifteen years of age, and must be able to pass a thorough examination

in arithmetic, geography, grammar, reading, spelling, and writing. A

candidate may pass into any of the more advanced classes should he be able

to pass an examination in all the previous studies of the course.

Students, however, who desire to study those subjects which specially

relate to agriculture, such as Chemistry, Botany, Animal Physiology. &c,

are received for a shorter period than the full course. The course of

instruction is as follows:—

First Year.—First

Term.—Algebra, History, and Composition. Second Term.—Algebra completed,

Botany, and Agriculture. Third Term.—Geometry, Botany, and French.

Second Year.—First

Term.—Geometry, Elementary Chemistry, and French. Second

Term.—Trigonometry, Surveying, Organic Chemistry, French. Third

Term.—Mechanics and Analytical Chemistry.

Third Year.—First

Term.—Mechanics, Drawing, Agricultural Chemistry, Horticulture. Second

Term.—Entomology, Physics, Rhetoric. Third Term.—Astronomy, Meteorology,

English Literature.

Fourth Year.—First

Term.—Physiology, Agriculture, Mental Philosophy. Second Term.—Zoology,

Geology, Botany, U. S. Constitution, Moral Philosophy. Third Term.—Civil

Engineering, Political Economy, Landscape Gardening, Logic.

The subjects discussed in

the lectures on Practical Agriculture which are delivered to students of

the first year are the general principles of drainage; laying out and

construction of farm drains; and sewerage of buildings; principles of

stock-breeding; breeds of domestic animals,—their characteristics and

adaptation to particular purposes. And then the fourth year's students

receive lectures on the History of Agriculture; on the principles of farm

economy; mixed husbandry; rotation of crops; relation of live stock to

other interests of the farm; feeding of animals; management and

application of manures; planning and construction of farm buildings; farm

implements; cultivation of farm crops; special systems of husbandry. The

lectures on Agricultural Chemistry refer to the formation and composition

of soils ; the relations of air and moisture to vegetable growth;

connection of heat, light, and electricity with growth of plants; nature

and source of food of plants; chemical changes attending vegetable growth;

chemistry of the various processes of the farm, as ploughing, fallowing,

draining, &c.; preparation, preserving, and compositing of manure;

artificial manure; methods of improving soils by chemical means, by

mineral manures, by vegetable manures, by animal manures, by indirect

methods; rotation of crops; chemical composition of the various crops, and

the chemistry of the dairy.

The lectures on Botany make

pointed reference to the relation of that science to agriculture, and

include the study of all agriculture grasses and plants. In the course on

Physiology very special attention is bestowed on the anatomy and

physiology of the domesticated animals, and actual dissections of animals

are made in presence of the students.

An examination takes place

at the end of each study; and unless the student makes seven marks out of

a possible of ten at the concluding examination, and an average of five at

the stated examinations during the term, he is not recorded as having

passed. Each student, unless physically disabled, is required to work

three hours per working-day, excepting Saturday, on the farm or on the

garden; and remuneration is allowed according to ability, the maximum rate

being 10 cents. (fivepence) per hour. The arable part of the farm—300

acres in extent—is worked under a regular six-course rotation of Indian

corn, turnips, oats, wheat, and clover; while a series of experiments are

being constantly carried on with the view of "educing principles which lie

at the foundation of agriculture." All these operations the students have

to witness and aid in, under the supervision of the Professor of Practical

Agriculture. Specimens of the different breeds of cattle—Shorthorn,

Hereford, Devon, Ayrshire, Galloway, and Jersey; of Southdowns, Cotswold,

Lincoln, Spanish Merino, and black-faced sheep; and of Essex, Suffolk,

Berkshire and Poland China swine, are kept on the farm with the view of

providing to students an opportunity of becoming acquainted with the

characteristics of all these various breeds, and with the view of

illustrating what is taught in the class-room. The buildings include a

very fine chemical laboratory, containing experimenting tables for forty

students; as also an excellent library and museum, the former containing

about 4000 volumes, and the latter about 5000 models of mechanical

inventions relating chiefly to agricultural manufactures and engineering.

The staff at present

consists of a Professor of Mental Philosophy, who is also President or

Rector, a Professor of Chemistry, a Professor of English Literature, a

Professor of Zoology and Entomology, a Professor of Botany and

Horticulture, a Professor of Practical Agriculture, and a Professor of

Mathematics and Civil Engineering, and seven assistants. The salaries of

these Professors amount to from 1000 to 2000 dollars, or from £200 to £400

per annum, the President having 3000 dollars or £600. The number of

students in attendance is about 150, and since the college received the

land grant in 1862, 123 have graduated, The degree of Bachelor of Science

is conferred upon all students who go through a full course and sustain

all the examinations; while the degree of Master of Science is bestowed

upon those graduates of three years' standing, who give evidence of having

during that period made a proper proficiency in scientific studies.

Education is free to all students, and board and washing are furnished at

cost. A fee of 5 dollars (£1) is charged for matriculation, and a similar

fee for graduation; while students in analytical chemistry have to pay 2

dollars (8s.) the second term, and 10 dollars (£2) the third term for

their outfit in the laboratory. Each student is charged 1 dollar and 25

cents (5s.) a term for room-rent, and has to provide himself with all

necessary furniture except bedsteads and stoves, which are afforded by the

college. The college accounts for 1875 show the revenue for that year to

have been 53,375 dollars or £10,675; and the expenditure 53,115 dollars or

£10,623.

Ontario Agricultural

College.—Though slower in moving in the matter than the United States,

Canada has at length bestowed practical attention on the disemminating of

scientific agricultural education. Four years ago the Government purchased

a farm extending to 550 acres, and situated about a mile to the south of

the town of Guelph, in the Ontario province, and converted it into a

"School of Agriculture and Experimental Farm," with the view of giving a

thorough mastery of the practice and theory of husbandry to young men of

the province engaged in agricultural or horticultural pursuits, or

intending to engage in such; and conducting experiments tending to the

solution of questions of material interest to the agriculturists of the

province, the results of such experiments to be published from time to

time. The college was opened in May 1874, and already a good beginning has

been made, though as yet of course little real substantial work has been

accomplished. Buildings have been erected to accommodate about a hundred

students, and the farm, 400 acres of which are clear, has been greatly

improved; while the facilities for imparting scientific and practical

education have been considerably increased and are now pretty complete.

The farm has been divided into five departments, viz.—1, Field department;

2, live stock department; 3, horticultural department; 4, mechanic

department; and 5, poultry, bird, and bee department, with a foreman or

instructor for each of the first four. The farm has been provided with an

extensive stock of implements, including all the latest and most improved

inventions; while the live stock department consists of from three to ten

of each of five different breeds of cattle, viz., Shorthorn, Hereford,

Devon, Polled, and Ayrshire; of a few of each of four different breeds of

sheep, viz., Leicester, Cotswold, Dereham, Longwools, and South Downs ;

and a few Berkshire and Windsor swine; and of sixteen or eighteen farm

horses, rather better than the general run of farm horses in the Dominion.

The majority of the cattle and sheep and a few swine were imported from

England and Scotland in the summer of 1876 by Mr William Brown, Professor

of Agriculture at the College. They were selected from the following herds

and flocks and bought at high prices, viz., the Shorthorn from Her

Majesty's herd at Windsor, and from Mr Campbell's herd at Kinnellar,

Aberdeenshire; the Herefords and Devons also from Windsor; the Polled

cattle from the herd of the Earl of Fife, at Duff House, Banff; of Mr

Farquharson, at Haughton, Alford, Aberdeenshire; and of Mr Hannay, at

Corskie, near Banff; and the Ayrshires from the herd of the Duke of

Buccleuch in Dumfriesshire ; the Border Leicester sheep from Mr Ferguson,

Kinnochtry, Coupar-Angus; the Oxford Devons from Mr H. Brassey, of Oxon;

the Longwools from Mr Hugh Aylmer, West Dereham Abbey, Norfolkshire; and

the Prince Albert Windsor swine from Her Majesty's stock. Generally

speaking, these animals have done well at their new home, and certainly it

must be admitted that they form a most promising nucleus of a breeding

stock. The main object in having specimens of all these different herds at

the college is to give students a practical acquaintance with all the

various characteristics of each—their excellencies, defects, and

peculiarities; and though it may have been costly it assuredly was a wise

move to come to the fountainhead and secure the best animals to be had for

the purpose required. It can hardly be said that the same care and

enterprise have characterised the selections of stock for all the United

States colleges; and no greater mistake could be made than to illustrate

lectures on the characteristics of a certain breed by an untrue or

unfavourable specimen of that breed. A portion of the land has been set

aside as an experimental farm; and already a series of experiments on a

great many varieties of grain, roots, and grasses, under different

treatment regarding cultivation and manuring have been begun, and have

thus far gone on satisfactorily. The whole work of these experiments has

to be executed by the students, under the superintendence of the

professors of agriculture and chemistry, one of the students being

selected each year as responsible overseer of the experiments. Important

experiments are also conducted in the feeding of live stock.

The curriculum or course

extends over two years; and students must be fifteen years of age before

they are admitted, and able to pass an examination in ordinary elementary

education, or what is known as the three R's in this country, and also

produce a certificate of intention to follow agriculture or horticulture

as an occupation. Students who cannot pass the entrance examination are

admitted, if desired, into a preparatory class in which they are taught

for a year on ordinary elementary subjects, including farm and garden

work, if they have hitherto had no knowledge of these occupations.

The instruction given is

divided into two parts—1, a course of study, and 2, a course of

apprenticeship; the former having reference to the theoretical and the

latter to practical instruction. A special winter course, consisting

almost entirely of lecture-room work, and covering in two winters the

whole course of theoretical instruction, is provided for farmer's sons and

others employed in farming who have to return to their occupations in

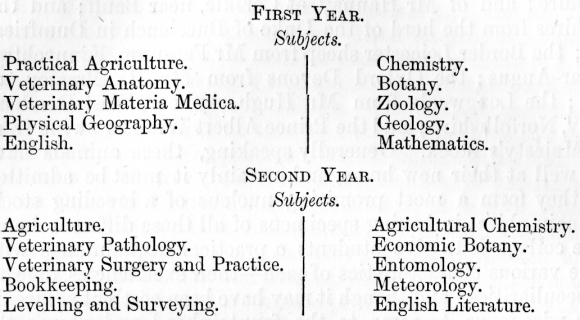

spring. The course of study is as follows:—

The course of

apprenticeship consists of practical instruction in all the four principal

departments of the farm—the field, the live stock, the horticultural, and

mechanical departments—the instructor of each department or his assistants

accompanying the students, who are distributed alternately to each branch,

so that in the course of the two years they obtain a thorough insight into

all matters connected with these four departments.

There are two sessions in

each year—a winter session, beginning at the first of October, and a

summer session, commencing about the middle of April—each session being

followed by an examination and a short vacation. Diplomas are given to all

students who complete the required course satisfactorily, and negotiations

have been opened with the view of having these diplomas or degrees issued

by the University of Toronto. Here, as at the United States colleges,

tuition is free, while students receive board and washing at cost. It is

preferred, but not required, that students should reside at the college.

Students who take the regular course have to work an annual average of

five hours per week day in either of the four departments of the farm, and

for this they receive remuneration to the extent of 10 cents, or 5d. per

hour. This labour system has many great advantages, and one of the most

important is that it reduces the cost of education at the college to a

very small amount. It is calculated that at the most the cost of the whole

two years should not be more than 100 dollars, or £20. An industrious

student, with a fair knowledge of practical farm work, might almost pay

his way through.

The staff at present

consists of a President or Rector, who is also Secretary and Bursar; a

Professor of Agriculture, a Professor of Chemistry, a Professor of

Veterinary Science, an instructor in the farm department, an instructor in

the horticultural department, and an instructor in the mechanical

department. Up till last autumn (1877), when a large addition was

completed so as to bring the capacity up to 100 students, the college

buildings could accommodate about 40 students. Every room was then filled,

and there is little fear that the greatly increased accommodation now

provided will be found unnecessarily large. In fact, the buildings are

already taxed to their utmost, no fewer than 100 students being enrolled

for the winter session of the present year (1877), which begins on the 1st

of November—a month later than usual, owing to the new buildings not

having been finished sooner. The financial side of the subject is not the

least important. From the experience already obtained, it is quite evident

that the farm will be self-supporting, and, as previously stated, students

pay for their board and washing, so that, once everything has been got

into proper working order, almost the only item to be placed on the

maintenance account will be the salaries of the staff and wages of

assistants, which at present amount to 8760 dollars, or £1752 per annum.

Mr Johnston, the able and energetic President of the College, assured the

writer that once the college and farm were fairly established, he believed

he could carry on the institution with an appropriation of about 10,000

dollars, or £2000 per annum. The cost of maintenance (including

experiments, salaries, and wages) in 1876 amounted to about 17,000

dollars, or £3400; and it is estimated that the appropriation expenditure

for this year (1877) will amount to about 500 dollars, or £100 more.

In mid-summer (1877) the

writer had an opportunity of seeing into the working of this college and

its farm very fully, and it was indeed wonderful and gratifying to find

everything moving on so systematically and efficiently in an institution

which had only recently entered the third year of its existence. The staff

seem most efficient, and work harmoniously together towards the same good

end—the complete success of their institution. The students were employed

mainly at outside work—some cutting and gathering pease, some carting,

some tending to live stock, some gardening, some engaged among the

experimental plots, and some handling the plane, saw, and chisel in the

mechanical department. The tone throughout seemed healthy and promising.

Indeed, one could not fail to see in this youthful institution the

foundation and beginning of a seat of agricultural learning that will be a

boon, a blessing, and an honour to the great country that gave it

existence. Short as the history of the college is, it is not altogether

without the stamp of discontent. A few impatient citizens of the Dominion

have been grumbling because the college has as yet "done no good to the

country." It has a great work to accomplish, which, like all great works,

can be accomplished only by slow degrees.

Scientific Agricultural

Education in Scotland.—Thirty-eight Agricultural Colleges in the United

States! How many in Scotland? Surely it must seem to every one a little

strange that that region of the globe where agriculture has become most

truly a branch of science should, of almost all civilised nations, be the

most devoid of means for imparting scientific agricultural education. No

country in the world stands more in need of a knowledge of science as it

relates to husbandry than Scotland, and yet few countries have less of it,

or so little means of obtaining it. "With a large and constantly

increasing population, and but very limited scope for extending either our

arable or exclusively meat-producing areas, we must do either of two

things—send our money into foreign countries for meal and meat, or bring

more out of the acres we have got. The latter course ought to be ours.

Increased acreage production has become an urgent necessity if land in

Scotland is to maintain its value to its owners, and Scottish farming

remain a remunerative profession. Farming in Scotland has changed greatly

within the past twenty years. The farmers of to-day have to contend with

rents greatly advanced and still increasing, with labour bills doubled and

probably not yet at their maximum, and with manure accounts tripled and

still growing; while, on the other hand, their receipts for grain have

remained almost steadfast, and those for beef and mutton, which for a time

advanced satisfactorily, seem at last to have reached their highest point.

To be sure, a little more may yet be done in many localities, by the

better exercise of the knowledge and appliances now at the command of the

farmer, but there are mysteries in the tillage of the soil and the

management of live stock that science alone can unlock for him. There are

treasures in the soil and in the animal which are not made visible to him

by his elementary "binocular," and which can be revealed to his sight only

by chemistry and physiology—treasures which, if he is to maintain an

advancing rent, increasing labour and manure bills, and his position in

society, must yield to him their richness and substance.

The encouragement given to

the study of scientific agriculture by the Highland Agricultural Society

has already done much good, and will still do more; and so also will the

laudable efforts of the North of Scotland School of Chemistry and

Agriculture, recently established at Aberdeen. Both these movements are

good as far as they go, and their promoters deserve all honour and praise

for the service they have rendered to agriculture. But neither of the two

meets exactly what is wanted by the general body of Scottish farmers. The

classes conducted in Edinburgh, taking living and everything into account,

are too costly for a very large number of farmers' sons, and, of course,

the valuable bursaries offered by the Highland and Agricultural Society

can aid but a very few. The institution in Aberdeen, again, has still

greater defects, and though it is merely of a tentative character,—merely

a small beginning,—a foundation on which much is intended to be built, it

would be well not to allow its inefficiency to lie unnoticed, lest its

energetic promoters should rest too long contented with what they have

already achieved. The classes in Aberdeen are carried on in connection

with the Science and Art Department, and continue weekly from the 1st of

November to the end of March. The course consists of lectures on

agricultural chemistry, botany, and practical agriculture, one very good

feature being a teachers' class, which was formed as an opportunity for

schoolmasters to qualify themselves to teach scientific agriculture in

their schools, and obtain the grant given by the Science and Art

Department for these special subjects. These classes form an important

step in the right direction, but their promoters must not leave them as

they are, for they are faulty and insufficient for the end in view in

several points. One of the chief defects of the present system is that it

practically confines the classes to pupils residing either in the city of

Aberdeen, or within a radius of fifteen or twenty miles, for the latter

distance is certainly as great as a student could be expected to travel

once a week to attend a lecture, lasting for two hours, or perhaps only

one hour. A school of agriculture confined to so limited a district is too

distinct an error to demand any argument.

Far better than the present

system of weekly lectures would be the establishment of a "winter

session," beginning about the 1st of January and extending over say six

weeks or two months, during which lectures should be delivered every

lawful day, excepting Saturday, on agricultural chemistry, physiology and

veterinary surgery, and practical agriculture, and occasionally, if

possible, on geology and botany. An examination should be field once every

week, on Saturday, on the three principal branches of study, and at the

end of the session, on all the subjects taught, and a list of the order of

merit published, each student receiving a certificate according to the

grade in which he passed.

The compressing of the

course of lectures into a short session of six weeks or two months would

virtually throw it open to the whole country; and then its inexpensiveness

(the whole session might be gone through for something like eight guineas)

and the quiet, it might almost be said idle, season of the year at which

it would be held, would put it within the reach of all classes of

prospective farmers. Another very important advantage of the compressing

of the weekly lectures into a regular session would be the more elevated

tone which it would give to the instruction provided. The writer has

attended both university and science and art classes, that is, every-day

lectures and weekly lectures, and was very strongly impressed with the

difficulty in keeping up the interest in the subjects taught at the latter

as compared with those at the former.

But useful as are the

existing classes, and as would be the session suggested, they cannot give

to Scotland all that it requires in the way of agricultural education.

Nothing less than a fully equipped college with experimental farm, such as

have been established in Canada, can ever suffice to meet the demands of

the country; and surely it is not too much to hope that some day we will

follow the good example shown us by our enterprising "cousins" across the

Atlantic. No' one, it may be presumed, will deny that Scotland has more

need for scientific agricultural education than either the United States

or Canada; and if these countries can afford to establish colleges for

their young farmers, surely we ought to be able to do so too. It has been

said that the agricultural mind in Scotland is not yet greedy enough in

its cravings for scientific agricultural education to demand the

establishment of a Scotch agricultural college; and if that is so, it

certainly is full time that an effort should be made to educate it up to

that point. The subject certainly does require ventilation and discussion,

and the writer's object is to spread and intensify both. Let our farmers

contemplate for one moment what a grand thing it would be for Scotland to

have such an agricultural educational institution as that which Canada

boasts of; let them think what a benefit it would be for the coming

generations of farmers to have within their reach such a thorough

professional training as that which has been offered to young

agriculturalists in Canada; let them contemplate how much light and shade,

and how much of that which is entertaining and attractive to the

intelligent mind would be imparted to agriculture by a college training;

let them remember that this typical college is not an institution that

imparts to young men merely artificial ideas of things, as it is argued

some agricultural colleges do, but an institution that combines the

practical with the theoretical, an institution where the student listens

to lectures the one hour and handles the plough or spade the next, where

he can witness experiments, and where, in all departments, studies, and

actions, economy rales supreme; let them consider and think over all these

and many other points that connect themselves with the subject, and we

shall very soon hear from our farmers a unanimous demand for a "Scotch

Agricultural College and Experimental Farm." The inauguration of that

institution, if we ever reach that stage of intellectual advancement, will

be a brilliant event in the annals of Scottish farming. |