|

By the Rev John Gillespie,

A.M., Mouswald Manse, Dumfries.

Premium—The Gold Medal.

Extent of the Breed at

different periods.

The province of Galloway,

from which the above valuable breed of beef-producing cattle has taken its

name, is now much more limited in area than it was in ancient times. Many

centuries ago the term Galloway was applied to the western half of that

part of North Britain which lies to the south of the Firth of Forth; thus

Dumfriesshire, Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire and Ayrshire were included in the

province, as well as the two counties which now bear the name. Ancient

Galloway may be described generally as having comprised that extensive

tract of country lying to the west of the main line of the Caledonian

Railway from Carlisle to Glasgow. But for several centuries the term has

been confined to Kirkcudbright and Wigtown, which are termed respectively

the Stewartry and the Shire of Galloway. Until the second half of last

century, the Galloway was the only breed of cattle kept in the wider of

these two districts, comprising half a dozen counties which collectively

bore the name. Indeed, even after the title had come to be restricted to

Kirkcudbright and Wigtown, the southern of the three divisions of Ayrshire

was more celebrated for the superior quality of its black cattle than

these two counties. There is a well-known adage which says:—

Kyle for a man;

Carrick for a cow ;

Cunningham for butter and cheese;

And Galloway for woo'.

This saying is so remote

that its precise antiquity cannot be traced, but it must have originated

after the term Galloway came to be employed in its restricted sense; for

not only is the phrase made to exclude Ayrshire, but the sheep which

produced the fine wool referred to were confined to Kirkcudbright and

Wigtown. So closely were this breed of cattle identified with south

Ayrshire, that in the old statistical account, and in other writings of a

similar date, they are not uncommonly termed Carrick cattle. Ortelius [Mr

Thomas Farrall, in his prize report on the Ayrshire breed of cattle,

published in the eighth volume of the "Transactions" for 1876, quotes this

statement of Ortelius as referring to Ayrshires, whereas that valuable

race of milkers did not exist as a distinct breed until nearly two

centuries after the time of Ortelius. The brief description which that

foreign author gives of the cattle in Carrick corresponds closely with the

characteristics of Galloways, and not at all with those of Ayrshires.

Besides, all the native writers agree in testifying that the Galloway was

the only breed in south Ayrshire until near the end of last century. It

will be sufficient to give a quotation from the "View of the Agriculture

of Ayrshire" by Mr Aiton, who had the best opportunities of observation,

for he was for many years previous to 1785 a practical farmer in the

county. In his work published in 1811 he says:—"The Galloway cow, so well

known and so highly valued in the English market, was, till of late, the

only breed known in Carrick, and in former ages through the whole county

of Ayr ; and though the dairy breed has been lately introduced, and is

fast increasing in Carrick, still the Galloway cow is most common in that

district of Ayrshire" (Aiton's "View," p. 413).] the celebrated geographer

and author, who wrote in 1573, says:—"In Carrick are oxen of large size,

whose flesh is tender and sweet and juicy."

While Galloway has from

time immemorial been the home of the cattle of that name, yet they were

not very numerous in any part of it until about the close of the first

quarter of the eighteenth century. Previous to the union of the two

kingdoms there were comparatively few cattle kept even in the arable

districts, the low lands as well as the hill country being at that time

stocked principally with sheep. And the explanation of this is not far to

seek. The towns in Scotland were not populous, and consequently the demand

for beef from them was very limited; and, moreover, in consequence of the

distance of the greater portion of the wide district where Galloways were

kept from the principal centres of. population, it did not participate to

any considerable extent in the limited demand which did exist. The feuds

between the Scotch and the English prevented any outlet even for store

cattle to the other side of the border, so that cattle breeding at this

period was not remunerative. From the deed of settlement of Giles Blair,

Lady Row, who lived in Carrick, executed on the 31st August 1530, it

appears that a cow at that time was worth 2s. 2d. sterling; an ox, 2s.

6d.; a two-year old, 1s. 1d.; and a stirk, 8d. Sheep were more profitable

than cattle, and they were valuable mainly for their wool, for which there

was a good demand at fair prices. Consequently those portions of the

arable farms which were not employed for cropping purposes, as well as the

high lands, were principally stocked with sheep. But the union of the two

kingdoms opened up a demand for lean cattle from Norfolk and the other

south-eastern counties of England, which early last century caused a

speedy extension of cattle-breeding, and this was found to be much more

remunerative than any system which had yet been tried. The proprietors

were led to perceive the profit of having good grass on their estates,

seeing that the chief revenue of those who rented their lands must be

derived from cattle. With the view of reducing the extent under tillage,

and correspondingly increasing the area under grass, they immediately set

to work to enclose the lands with stone fences of a kind which have since

been known as Galloway dykes. In doing so, they in many instances threw

several farms into one, and thereby ejected a large number of tenants with

their families so summarily, that not a few of them, having no other means

of subsistence, soon found themselves in destitute circumstances. The

process of enclosing was for a time interrupted by the popular rising of a

body of men known as "The Levellers," whose lawless proceedings are matter

of history. But the rising was soon quelled, and the work of enclosing and

of stocking the fields with cattle went on apace. Sheep were almost

entirely banished from the low grounds, the only bleaters grazed in the

dales being a few pets, and these were kept for the sake of the blankets

and homemade cloth, which were made from their wool by the farmers' wives.

Andrew Symson, Episcopal minister at Kirkinner, who wrote his "Description

of Galloway" in the end of the seventeenth century, says:—"Galloway is

more plentifull of bestiall than cornes," so that the extension of cattle

breeding had begun in his day. The rise in the price of cattle was rapid

and great. The statement of John Maxwell of Munches, in his letter, dated

1811, to W. M. Hemes of Spottes, that in 1736 he saw 100 five-year-old

cattle sold at Dumfries for £2, 12s. 6d. each, is often quoted as an

illustration of the low prices obtained at that time; and so they were in

comparison with what was afterwards procured, but when contrasted with the

valuation which Lady Row put upon her cattle two centuries previously, the

rate mentioned by Mr Maxwell seems very large. The price in 1736 was

twenty-four times what it had been in 1530, and it ought to be borne in

mind that the principal rise in value had taken place during the fifty

years immediately preceding the date specified by Mr Maxwell. The trade of

sending lean Galloway cattle to the south gradually increased in

dimensions during last century, until at the close of it, and in the early

portion of the present century, as many as from 20,000 to 30,000 three and

four-year-old Galloway cattle were annually sent from the pastures in

Dumfriesshire and Galloway to England, and principally to the counties of

Norfolk and Suffolk. The adoption and gradual extension of turnip

husbandry, and the application about the same time of steam power, not

only did away with the trade, and led the farmers to prepare a large

proportion of their cattle for the fat market, but they brought back the

sheep to the arable lands, and thereby lessened the number of cattle kept,

at least in proportion to the increased produce from the soil.

Galloway cattle have been

entirely supplanted by the Ayrshires in the native county of the latter,

in Renfrewshire, and in Lanarkshire; the spotties have also driven them

almost entirely from Wigtownshire, and in the stewartry of Kircudbright

and Dumfriesshire this valuable and fashionable race of milkers has in a

large measure taken the place of the beef-producing black-skins. So lately

as 1810, Galloways were the prevailing breed in Carrick (Aiton's "View,"

p. 413) and in Wigtownshire the number of Ayrshires at that time was not

great. Shortly thereafter, the ancient cattle were rapidly displaced in

Ayrshire by the dairy cows, but it was not until after 1840 that any

serious inroad was made upon their numbers in Dumfriesshire and Galloway.

However, during the decade which followed that year the extension of the

dairy system was very rapid, and the number of the native breed was

correspondingly diminished. The depression under which the cheese trade

suffered caused a slight reaction in their favour, and the number of

Galloway herds has increased rather than diminished during the last few

years.

Galloway cattle have been

the native breed in Cumberland as far back as can be traced. This may be

explained in two ways. One is the fact that in very remote times that

border county was under the same rule as the part of Scotland lying

immediately to the north of it. When in course of time the two districts

of Cumberland and Dumfriesshire formed part of two different kingdoms, the

inhabitants on one side of the border cherished feelings of bitter

hostility towards those on the other side. Cattle lifting was a favourite

pastime of the borderers in those days; for an Englishman thought it

neither a sin nor a shame to steal a cow or a horse which belonged to a

Scotchman, and the latter did not blush in following the same practices.

It was true of the borderers as of the people in Bob Roy's country:—

"The good old rule

Sufficeth them; the simple plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can."

Now this interchange of

cattle, without either party ever dreaming of paying for the beasts which

they appropriated, being carried on as opportunity presented itself, the

breed of cattle which had originally been the same would continue

intermixed on both sides of the border. Not only were Galloways

extensively kept in Cumberland, but, as we shall see by-and-by, Riggfoot

and other places in that English county supplied the Cumberland Willie

(160) and other strains of blood which flow in the veins of all the best

Galloways now in the kingdom. While the Galloways have been largely

supplanted by the Ayrshires in Scotland, they have been considerably

displaced by the shorthorns in Cumberland, Northumberland, and other

districts in England, where at one time they extensively prevailed.

However, in recent times there has been a slight reaction in their favour

on the other side of the border, and in some instances shorthorn herds

have been dispersed and the blackskins put in their place. Among others

who have followed this course may be specified, Sir H. B. Vane, Bart.,

Hutton in the Forest, Penrith, who has established a select herd of high

class pedigree Galloways.

Origin of the Breed.

An allegation has never

been made in any well-informed quarter that the Galloway is not an

original and distinct breed of cattle. Galloway was long celebrated for

two other varieties of live stock, viz., sheep and horses, and in both

instances the more prominent characteristics of each breed have been

attributed to the importation of foreign stock. We have already quoted the

adage, "Galloway for woo'," and in corroboration of its soundness we may

cite the testimony of William Lithgow the traveller, who walked over the

district in 1628. He says that Galloway sheep produced finer wool than any

he had ever seen in Spain. "Nay," he continues, "the Calabrian silk had

never a better lustre or a softer gripe than I have touched in Galloway on

the sheep's back (Lithgow's "Travels"). From time immemorial this province

possessed and acquired celebrity for a distinct breed of horses, which

were deservedly much prized far and wide for their excellent qualities.

Indeed previous to the middle of last century, the phrase, " A Galloway,"

conveyed a very different meaning from what it does at the present day,

being then taken to designate, not the native cattle, but the sure-footed,

hardy, and spirited little horses of the district. There is a tradition

that these sheep and horses originated from animals which escaped from a

vessel of the Armada, which had been wrecked on the coast. This theory may

be true to the extent that the native breeds may have been improved by

being crossed with animals brought from Spain in the manner indicated, but

it is undoubted that both of these had acquired celebrity before that

ill-fated expedition was heard of. Though the precise age of the adage

referred to cannot be determined, yet it is unquestionably of older date

than the Armada, and therefore Galloway wool was "familiar as a household

word" before that expedition set sail from Spain. Again, Campden, whose

"Britannia" was published in 1586, specifies in that work the

characteristic qualities of Galloway horses. Further, these steeds must

have been so widely known as to have become proverbial for their

superiority in Shakespeare's days; for in King Henry IV., act ii. scene 4,

Pistol says to Doll:—"Thrust him down stairs! know we not Galloway nags?"

But whatever truth there may be in the tradition as to the origin of the

sheep and horses of Galloway, no such theory has ever been advanced either

in a written or oral form as to the origin of the distinct breed of cattle

for which the province has so long been distinguished.

We think there can be very

little doubt but that the Galloway and the West Highland breeds of cattle

have sprung from the same parent stock at a very remote date. There is a

close resemblance even at the present day between a well-bred polled

Galloway and a West Highlander minus the horns. Indeed, the similarity is

so great that when we bear in mind the fact that previous to the close of

the eighteenth century almost all the Galloways were horned, it is easy to

understand how any difference which now exists between the two types of

animals may have been produced by the different circumstances in which

they have long been placed, and the different treatment to which they have

been subjected. The habitat of the one has from the remotest ages been the

western part of Scotland, lying to the north of the Firths of Forth and

Clyde, while the western half of north Britain to the south of these

firths, was, as we have seen, the native home of the other. In short, the

one were the cattle of the western Highlands, and the other of the western

Lowlands of Scotland. The shaggy coats and the wild picturesque appearance

which the former now possesses and presents in comparison with the latter,

are only what could be expected from the one having been reared for

centuries in the

"Land of brown heath and

shaggy wood

Land of the mountain and the flood,"

and from the other having

been kept at a lower elevation, and better and more frequently housed, as

well as more liberally and carefully fed. The variety in colour which now

prevails in West Highland herds is no objection to this theory; for while

Galloways are now almost all black, many of them in former times were red

and brindled, and even at the present day pure bred animals with red skins

are occasionally to be met with.

History of the Improvement

of the Breed.

The work of improving the

Galloways was not begun until after there had arisen for them that demand

from the southeastern counties of England to which we have referred. It is

not surprising that previous to this time nothing had been done in this

direction, for in addition to the stagnation which prevailed in Scotland

in all departments of agricultural industry, the price which could be

obtained for even the best of them was so small that there was little

inducement to improve them. But the quickened demand and the greatly

enhanced prices naturally led the breeders to be at the use of means to

supply their southern customers with a better type of beast. There is a

tradition, which is believed to be well founded, that the original

Galloways were universally provided with horns (Aiton, p. 419). By what

means these appendages were first got quit of in a portion of the breed

there is no means of ascertaining, but it was in consequence of the

graziers in the south preferring them polled that the farmers in Galloway

were eventually led to select only animals without horns as breeders, and

so by-and-by the race became universally polled. Dr Bryce Johnstone, in

his "View of the Agriculture of Dumfriesshire," written in 1794, mentions

(p. 16) that most of the Galloways at that time were polled, and that the

ones which were so sold at upwards of 5 per cent. higher than those which

had horns. Mr William Stewart, Hillside, in an Appendix to the above work,

estimates the difference in value at as much as 20 per cent. and he says

that the cattle of Annandale, at the close of the first half of the

eighteenth century, were generally horned. Aiton, Smith, and Singer, who

wrote their views of Ayrshire, Galloway, and Dumfriesshire at the end of

the first decade of the present century, are at one in testifying that in

all districts very few of the Galloways at that time had horns.

No name stands out

conspicuous among his fellows as having been the chief instrument in

improving the Galloways at any particular period of their history. "Among

Galloway farmers have arisen no enthusiasts in the profession—none who

have studied it scientifically, or dedicated their talents almost

exclusively to this one object. No Bakewells, no Culleys, no Collings have

yet appeared in Galloway, who, with a skill the result of long study and

experience, have united sufficient capital, and by the success of their

experiments have made great fortunes and transmitted their names to the

most distant parts of the kingdom" (Smith's "Survey of Galloway," p.

237-8).

Nor was the early

improvement of the breed effected by the crossing of the native cows of

the province with bulls of other breeds, although it may be added that

isolated experiments of this kind were tried by several persons. Webster

in his "View of Galloway," published in 1794, particularises (p. 22) two

such trials which had recently been made—the one by the Earl of Galloway

with bulls from Westmoreland, and the other by Admiral Keith Stewart with

a West Highland bull brought from Argyllshire. Aiton (p. 415) mentions a

theory, but only to reject it, to the effect that it was by the use of

sires from Lancashire that the breed had been vastly improved, and that it

was through this cross that the horns had been got quit of in the Galloway

cow. But this admixture of foreign blood was so limited in extent that it

could have no perceptible influence in moulding the characteristics of the

breed generally at a time when Galloways were spread over such a very wide

area of country, and when there was almost no interchange of blood between

one district and another. There is no reason to doubt the assertion of the

last-mentioned author that "the breed was brought to its present improved

state by the unremitting attention of the inhabitants in breeding from the

best and handsomest of both sexes, and by feeding and management."

The improvement which has

been made upon them during the last fifty years has been very great, and

as this is an era within the memory of living men, the history of the

improvement wrought upon them during that period can be written with

greater minuteness and certainty. During the second quarter of the present

century, the district around Kirkcudbright and the eastern part of

Wigtownshire, possessed the best and finest specimens of the breed. A band

of skilful and enterprising men in these districts vied with each other in

their endeavours to improve the quality of their favourite blackskins, and

they were highly successful. Leading men of other localities got hulls

from these districts, several landed proprietors providing bulls for use

on their estates, Mr Hope Johnstone of Annandale and Sir James Graham of

Netherby being among the number. About 1830 the former gentleman imported

some splendid sires from Galloway, which were used in the herds of Mr

Gillespie, Annanbank, and others in Upper Annandale with such beneficial

results that the breeders in that district were ere long able to hold

their own in the show ring at the Highland Society and other meetings

against the exhibits of the men of Galloway. The best and most celebrated

bull taken to Upper Annandale by Mr Hope Johnstone was known as the

Castlewigg bull, from his having been the property of Mr Hathorn of

Castlewigg in Wigtownshire. He gained the first prize at Dumfries in 1830,

and was not only a splendid animal himself, but his produce were very

remarkable for their quality. Sir James Graham had what was a novel but

excellent plan to assist and encourage his tenants in their efforts after

improvement. Instead of medals or money, bull calves were given by him as

prizes to the Netherby tenants who showed the best lots of five yearlings

and as many two-year-olds ("Field and Fern," Scotland, South, p. 312). A

Cumberland tenant farmer, Mr George Graham, Riggfoot, used sires bred at

Borness and other places in Galloway, which not only raised his cattle to

the foremost place among herds of the breed at that time, hut his improved

stock was the fountain-head of all the best Galloways which have been bred

in subsequent times. Mr Graham has been termed by the Druid ("Field and

Fern," p. 311-12), "the 'Black Booth' of Cumberland and the border

counties," from his having done for Galloways what Booth has done for

Shorthorns; and there is no doubt but that the epithet is in a large

measure deserved, for to one animal in his herd almost all the best

pedigree animals can be traced in uninterrupted succession. This was

Cumberland Willie (160), or Borness as he was at one time called, from his

having been bred by Mr Sproat, Borness, near Kirkcudbright. His sire was

Galloway Lad (320). Cumberland Willie was the sire of a number of hulls

which were used in the best herds of Galloways in the south of Scotland,

and which were instrumental in effecting a marvellously rapid improvement

upon them. These were (1) The Squire (18), which, when chief of the black

harem at Meikle Culloch for three seasons, was the sire of several

splendid cows which laid the foundation of Mr James Graham's celebrated

herd. He was also the sire of Fergy (19), which was bred by Mr Graham, and

to which some of his best stock can be traced. The Squire, after leaving

Meikle Culloch, was used in the herds of Mr Walter Carruthers, Kirkhill,

of Wamphray, and John Graham of Shaw with most satisfactory results. He

was known in Upper Annandale under the name of the Blind Bull.

(2) Black Jock of Riggfoot

(66), own brother to the Squire (18), was used in the Kirkhill herd, which

had a high reputation for the superiority of the young males produced in

it, also in the herd of Mr Gillespie, Annanbank, whose females long took a

leading position in the show-ring.

(3) Brother to Mosstrooper

(67),the sire of Hannah (214), which was the dam of Semiramis (703) and

other cows whose produce have brought very high distinction to Mr James

Graham.

(4) Gaffer (162), the

property of Mr James Grierson formerly of Caigton, and now of Kirkland,

Dalbeattie, whose herd, long a famous one, was largely impregnated with

this blood.

(5) Geordie of Riggfoot

(234), long the chief of the black harem at Balig, Kirkcudbright, and the

sire of all the best of the celebrated old stock belonging to the Messrs

Shennan. Geordie of Riggfoot was the sire of Bob Burns (235), which had

such a distinguished career in the show-ring that he has been justly

termed "The Nestor of Black Bulls," and not a few of whose offspring have

been almost equally celebrated.

And (6) Mosstrooper (296)

which left his mark most permanently on the quality of the breed in

subsequent times. Mr Beattie, Newbie, Annan, bought Mosstrooper when he

was six years of age from Mr Gibbons, Mossband, Longtown; he won fifteen

first prizes in all, and never was beaten; when in his eleventh year he

was taken to the Paris show in 1856, and there occupied the premier

position among the polled Galloways, and, notwithstanding his age, he

attracted much attention and was greatly admired by the French, from the

Emperor and Empress downwards.

We have dwelt thus at

length on the Cumberland Willie tribe of Galloways because they are, as we

have already said, the fountain head of the greater number of pure-bred

animals of this breed—alike pedigree and non pedigree ones—in the south of

Scotland and the north of England. To trace his offspring further would be

very much like constructing a family tree from the Herd-Book, which could

be comparatively easily done, but which could not be kept within a

desirable compass. It is true that fresh strains flow into the Herd-Book

here and there, but these branches, according to the testimony of those

best qualified' to speak, or at least the greater number of them, grew out

at one time or other from the same stem, although, from their being only

recently entered in the Herd-Book, the exact point where the offshoot has

taken place not being chronicled cannot now be clearly traced.

At no previous period of

their history has so wide an improvement been made on the quality of the

Galloways in the kingdom as during the third quarter of the present

century, that is, from 1850 till the present time. From twenty-five to

thirty years ago, the purity of the breed generally over the country was

being rapidly corrupted by careless and injudicious crossing with other

varieties. The rapid extension of the dairy system at that time, to which

we have already referred, not only displaced the black-skins to a large

extent, but it also afforded an opportunity and even a temptation to an

admixture of breeds. Mr Charles Stewart, Hillside, Lockerbie, appreciating

this clanger, and realising the importance of maintaining the purity of

the ancient breed of the district, was chiefly instrumental in getting an

annual show and sale (by auction) of young bulls established at Lockerbie,

under the auspices of the Lockerbie Farmers' Club, which afforded ready

facilities for an interchange of blood between: the Annandale, Cumberland,

and Galloway breeders. We find it stated by one of the local newspapers in

its report of the first sale in 1851, that it was established "with the

view of giving an impulse to the breeding of Galloway stock, and

supplanting the half-breds of all crosses which have been gradually

deteriorating the blood of the old pure Galloways in the district." The

example of the Lockerbie Farmers' Club was followed in 1855 by the

newly-formed Galloway Agricultural Society, under the zealous and able

leadership of Mr Maxwell of Munches. In the spring of that year the first

sale of young bulls was held at Castle Douglas. At the outset the

Lockerbie show and sale surpassed those at Castle Douglas, both in the

number and quality of the bulls exhibited and sold, but ere long the child

outstripped the parent in both respects, and has ever since maintained its

pre-eminence. The improvement was so rapid that Mr Stewart stated at the

dinner after the sale at Lockerbie in 1855, that setting aside the 15 best

bulls of the 27 shown that clay, he was satisfied that the 16th in order

of merit was superior in quality to the one which was deservedly placed

first four years before; and he attributed this extraordinary progress

more to the sale than to the show. In that year upwards of 50 yearling

bulls were sold at the two sales, and these being spread far and wide

wherever Galloway cattle were kept, were the means of diffusing pure blood

through the country. The remunerative prices secured by the breeders gave

them a powerful stimulus

"in their efforts after

improvement. The prices realised at the first sales were much lower than

those reached since; at Lockerbie in 1851 the bull stirks sold at from £10

to £16 each for the best, and secondary ones were disposed of at from £7

to £10. In 1852 eighteen were sold at an average of £11, the highest price

being £22; in 1853 the first prize animal realised £21, 10s.; and in 1854

£23, 15s.; the Kirkhill lot in the latter year bringing an average of

nearly £20 each. These rates, though low in comparison with those current

now, were decidedly higher than the breeders had been accustomed to

receive when the sales were conducted privately. We remember that some

cautious people were wont to insinuate that enterprising and skilful

breeders who about the above time gave £20 or thereabouts for a bull

little more than twelve months old had more money than prudence or

judgment. But experience has shown that such investments were highly

remunerative, for prices have gradually gone up, the maximum being reached

at the sale in March last (1877), when £71 was given for Queensberry

(1027), bred by the Duke of Buccleuch, KG., sire Blaiket (548), dam

Melantho (1643) by Havelock (544), which was £1 more than had previously

been given, £70 being the price obtained in 1875 by Mr Maxwell Clark of

Culmain, for his fourth prize stirk. From £64 down to £40 have been

figures frequently reached at the sales during the last ten years. The

Duke of Buccleuch, though long an enthusiastic and most successful breeder

of Galloways, has only recently become an exhibitor at the Castle Douglas

shows, and in 1875 his Grace received the high average of £40 each for

half a score of yearling Galloway bulls.

The Lockerbie show and sale

have lost much of their prestige from the fact that the blackskins are not

numerous now in that part of the country, but the Castle Douglas ones were

never more prosperous than they are at the present time. In 1877 the

entries of one-year-old bulls numbered 126; one-half of them, it is true,

were indifferent in quality, and no great loss would have befallen the

breed if a considerable number of them had been castrated and destined to

the shambles. The excellent prices realised at the sales in preceding

years tempted many breeders to keep animals as bulls which are of

indifferent quality, but the unremunerative prices obtained for third-rate

non-pedigree beasts will effectually check the process of over production.

The other half of the yearlings exhibited at Castle Douglas in March last

were really fine animals, and those placed in the prize list—14 in

all—possessed in a very high degree the best characteristics of the race.

The Castle Douglas Bull

Show is a sort of "Derby Day" for the breeders of Galloways, as there is

great emulation among them who is to produce the best male animal of the

year. The prize being regarded as "the blue ribbon" of the Galloway Herd.

the winner of it is regarded as a sort of chief for the season. It may be

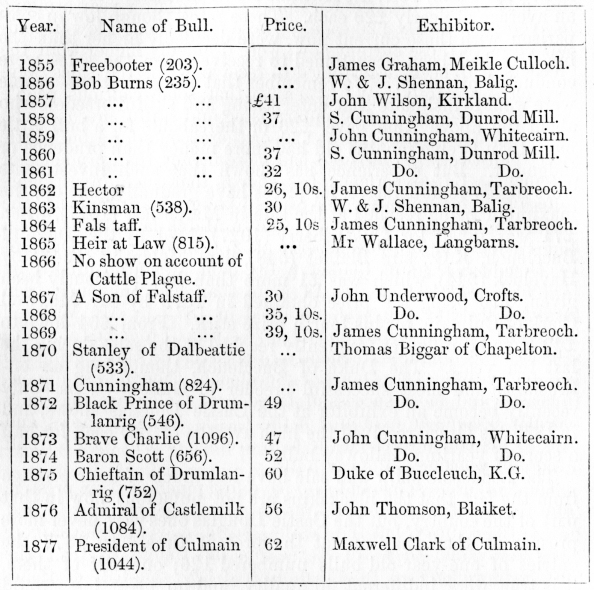

interesting to place on record the names of the winners in each year since

the show was started, with the names of the successful animals, and the

prices which each realised at the sale.

First Prize Winners at Show

of Yearling Bulls at Castle Douglas.

The Galloway Agricultural

Society established in October 1875 a show and sale of heifers at Castle

Douglas; it has been held annually, and been moderately successful. It has

afforded persons desirous of founding new herds or of recruiting old ones

a favourable opportunity for procuring well-bred pedigree animals, and the

prices obtained have been fairly remunerative to the breeders.

The establishment of a

Polled Herd-Book has been very influential in improving the breed of

Galloway cattle. It does not lie within the object of the present paper to

discuss the advantage of breeding from pedigree animals with any class of

stock, but we may merely state one illustrative fact. At the Castle

Douglas Bull Show in March 1877, the judges had merely the competing

animals before them, with no note of their ancestry. All the nine bulls

placed were from pedigree stock, not even one of the non-pedigree beasts

having secured a place on the list. As is well known, the Polled Angus or

Aberdeen cattle and the Galloways were until the current year (1877)

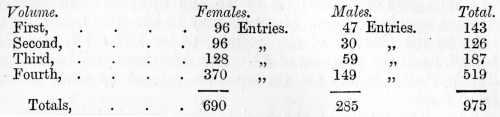

entered in one Polled Herd-Book. Four volumes of it has been issued, the

number of Galloways entered in each volume being as under:—

It was felt that though the

two breeds of Scotch polled cattle have strong points of resemblance to

each other, yet being distinct varieties it was desirable to have a

separate Herd-Book for each, all the more so that their respective homes

are so far apart from each other. Moreover, the Polled Herd-Book

being-private property, the breeders had no power to fix the

qualifications which animals ought to possess to entitle them to admission

into the Herd-Book, and in fact no control over its management in any

respect. There was the additional drawback that the proprietor and editor

of it—Mr Ramsay of Banff—residing at such a distance from the head

quarters of the Galloways, came so little personally into contact with the

breeders that the entries of animals of that breed could not be expected

to be so numerous as was desirable. On the 9th April 1877, the breeders of

and others interested in Galloways held a meeting at Castle Douglas, at

which it was resolved to form a Galloway Cattle Society for the management

of a Galloway Herd-Book. It was obviously desirable that the new Society

should possess the copyright of the Galloway portion of the Polled

Herd-Book, and accordingly negotiations were opened with Mr Ramsay through

a Committee of the Society— of which Mr Maxwell of Munches was the

Convener—with the view of effecting the purchase of it. These were

successful, the price paid being £75. A fund was raised by subscription to

defray the purchase money, and to provide such an additional sum as might

be necessary for putting the Society into working order, and in two months

about £160 was collected from 94 subscribers. The following are the Rules

and Regulations of the Galloway Cattle Society, agreed to at a meeting on

20th June 1877:—

"I. The name of the Society

shall be 'The Galloway Cattle Society.'

"II. The objects of the

Society shall be—

"(1) To maintain unimpaired

the Purity of the Breed of Cattle known as Galloway Cattle, and to promote

the Breeding of these Cattle.

"(2) To collect, verify,

preserve, and publish in a Galloway Herd-Book the pedigrees of the said

Cattle, and other useful information relating to them.

"III. All Subscribers of

10s. and upwards to the Fund for the purchase of the copyright of the

Galloway portion of the Polled Herd-Book shall be deemed original Members

of the Society. The Managers of Subscribers of £5 and upwards shall also

be deemed members. New Members may be admitted from time to time by the

Council of the Society, under Rules IV. and VI. hereof, upon the payment

of £1. Non-Members shall be charged double Entry Money for the animals

entered by them in the Herd-Book.

"IV. The affairs of the

Society shall be administered by a Council, consisting of a President,

Vice-President, Secretary and Treasurer (who shall be elected annually),

and Fifteen other Members of the Society (who shall be elected for three

years, and Five of whom shall retire annually in the order in which their

names stand upon the list).

"V. The Council shall have

full power

"(1) To hold Meetings at

such times and places as they may fix; at all Meetings of the Council Five

shall be a quorum.

"(2) To fix and determine

the terms and conditions on which Entries may be made in the Herd-Book.

"(3) To draw up from time

to time Rules embodying the qualifications which Animals must possess, to

entitle them to be entered in the Herd-Book.

"(4) To appoint an

Editorial Committee and Editor, for the purpose of collecting, verifying,

and arranging the Pedigrees of Animals proposed to be entered in the Herd

Book. Any person who is dissatisfied with the resolution of the Editorial

Committee, as to the admission of an animal to, or its exclusion from, the

Herd-Book, may appeal to the Council, whose decision shall be final.

"(5) To determine the time,

mode, and terms of issue of the Herd-Book, and other publications of the

Society.

"VI. The Annual Meeting of

the Society shall be held at Dumfries, on the Second "Wednesday of June,

to receive the Re-port of the Council, to Audit the Treasurer's Accounts,

to fill up the Vacancies in the Council for the ensuing year/and to

transact such other business as may fall to be disposed of. Extraordinary

General Meetings of the Society may be called by the Council at any time.

"VII. It shall not be

competent to alter any of the foregoing Rules, except at a General Meeting

of the Society; and notice of any proposed alteration must be lodged at

least 21 days before the Meeting, in writing, with the Secretary, who

shall specify it in the circular or advertisement calling the Meeting."

The Duke of Buccleuch, KG.,

is President of the Society: The Earl of Galloway Vice-President, and Mr

Maxwell of Munches Chairman of the Council. The Galloway Entries in the

Polled Herd-Book have been carefully re-edited, and they are about to be

issued as the first volume of the Galloway Herd-Book. Entries are being

received for the second volume, [Since the above was written, vol. ii.

part 1 of the Galloway Herd-Book has been published, containing 619

entries—433 females and 186 males.] for which animals are eligible without

pedigree on either side, provided the Council are satisfied that they are

from a pure-bred stock, but it has been resolved by the Council that only

animals which have pedigree on at least one side will be admitted into

future volumes. The Society has been inaugurated under highly favourable

circumstances, and its formation promises to be an important era in the

history of the breed.

The Council has made a

remit to its Editorial Committee to draw up a statement of the points of

Galloway cattle.

Properties of the Breed.

It is chiefly as a

beef-producing race of cattle that the Galloways are valuable; for their

milking properties are generally not of a high order. The milk given by

them is rich in quality, but as a rule the quantity is not large, at all

events in proportion to the size of the animal and to the food which it

consumes. However, the milking faculty runs in some strains, and

individuals of them are excellent dairy cows—from 10 to 13 lbs. of butter

per week being occasionally got at the height of the grass when they are

grazed on old pasture. However, such a yield is quite exceptional; and it

cannot but be admitted, even by the most ardent admirer of the breed, that

where the main object of a herd is dairy produce—either in butter or

cheese, but especially the latter—the Ayrshires are preferable to the

Galloways.

It has been said by the

author of "Field and Fern" (p. 317) that " there is no better or finer

mottled beef in the world than the Galloway and Angus," and the truth of

the remark has been long-placed beyond question by the fact that in the

Smithfield and other leading markets it has always commanded the highest

quotations. To a similar effect Mr M'Combie says, "There is no other breed

worth more by the pound weight than a first class Galloway."

It has been alleged in some

quarters that a Galloway is rather slow in coming to maturity in

comparison with some other varieties. Mr M'Combie says ("Cattle and Cattle

Feeders," p.17), "Although the Galloways are such good cattle to graze,

they are not so easily finished as our Aberdeen and Angus or cross-bred

cattle. They have too much thickness of skin and hair, too much timber in

their legs ; they are too thick in their tails, too deep in their necks,

too sunken in the eye, for being very fast feeders. It is difficult to

make them ripe; in many cases it is impossible, even though you keep the

animals until their heads turn grey. You can bring them to be three

quarters fat, and there they stick ; it is difficult to give them the last

dip." While there may be some slight ground for these allegations, yet

they are greatly exaggerated; and besides, it ought to be borne in mind

that the Galloways have not got the same justice done to them in preparing

them for the fat market as the other beef-producing breeds. It is very

seldom that the feeders of Galloways have forced them to the same extent

as has been done with the Angus, and consequently the distinctions which

the former have won at Smithfield and other fat shows have been neither so

numerous nor so great as those achieved by the north country darkies.

Still in 1872 Lalla Rookh (2142), bred by Mr Biggar of Chapelton, and

which had gained the first prizes as a yearling and two-year-old heifer at

the Highland and Agricultural Society's Shows at Dumfries in 1870 and at

Perth in 1871, carried off the first prize at Smithfield in the Polled

Class. Mr M'Combie won with a Galloway bullock at Smithfield and

Birmingham, and in 1861 he also took high honours—including the cup at the

latter place—with a Galloway heifer bred by the Duke of Buccleuch. The

feeders who have made it their aim to bring Galloways early to maturity

have accomplished results which for profit will compare not unfavourably

with those attained with any other breed. Mr Biggar of Chapelton, for

instance, averages £1 per month for his cattle till they are disposed of

at two years old. In 1866 six bullocks made £19 each when 15 months old;

in 1867 four made £23 at 20 months, and in 1873 the lot made 30 guineas at

24 months.

The hardiness of their

constitutions, and their plentiful covering of black hair which in well

bred ones is of the right sort, and which forms an excellent protection to

them in their native climate, which is very moist and occasionally very

cold, make them peculiarly well adapted for high lying and exposed

situations. Mr M'Combie's testimony on this point is well worthy of being

quoted, being the result of extensive and pretty lengthened experience.

"As to the Galloway cattle, they also have had a fair trial with me. I was

in the habit of buying for years from one of the most eminent judges of

store Galloways in Britain— Captain Kennedy of Bennane—a lot of that

breed. He selected them generally when stirks from all the eminent

breeders of Galloway cattle, and bought nearly all the prize stirks at the

different shows. In fact he would not see a bad Galloway on his manors.

The Galloway has undoubtedly many great qualifications. On poor land they

are unrivalled, except perhaps by the small Highlanders. Captain Kennedy's

cattle always paid me: they were grazed on a 100-acre park of poor land—so

poor indeed that our Aberdeens could not subsist upon it,"

For crossing purposes the

Galloways are deservedly held in high estimation. An excellent cross—which

is a special favourite with the butchers—is produced from the Galloway cow

and the shorthorn bull. The colours of animals of this cross vary a good

deal, but they are generally of a blueish grey. The infusion of the

shorthorn blood into them tends to make them come early to maturity, and

thereby counteracts the objection which Mr M'Combie has stated against the

pure-bred Galloways, that they are slow to take the last dip. Moreover,

their beef is of the same excellent quality as that of the breed to which

their dams belong, and much superior to that of the breed of their sires:

for there is considerable truth in the criticism which we have heard

expressed regarding shorthorns, that "they are too much like ladies'

maids—all show outside." Not a few excellent authorities use the Galloway

bull for crossing with the shorthorn cow, alleging that this cross is

preferable to the other. Galloway sires are also pretty extensively used

for crossing with Ayrshire cows, the produce being superior beasts, which

grow to a good size and weight, and come early to maturity. This cross is

cultivated principally by dairy farmers who combine dairying with the

rearing and in some instances also with the feeding of such cross-bred

cattle.

Galloway Blood in other

Breeds of Cattle.

There is, so far as we are

aware, only one other breed of cattle which now ranks as a distinct

variety of British cattle in the moulding of which Galloways have

exercised if not a preponderating at least a very considerable influence.

These are the Norfolk and Suffolk red-polled cattle. There is still a

close resemblance in figure if not in colour between the darkies of the

south west of Scotland, and the blood-red polled cattle of the above

English counties. In fact the likeness is so close, that bearing in mind

the fact that Galloways, many of which in former times were red and

brindled in colour, were taken to Norfolk and Suffolk in large numbers in

the beginning of last century, if not earlier, and also subsequently, it

is not unnatural to surmise that the present race of south country red

polls owe their origin at least in a large measure to the imported cattle.

Mr Marshall, who resided in Norfolk from 1780 to 1782, says in his book

entitled "The Rural Economy of Norfolk," that long before his time

Galloway bulls were used for crossing with the Norfolk home breeds. In the

recently published work on "The Cattle of Great Britain," edited by Mr

Coleman, the author of the article on the "Norfolk and Suffolk Red-Polled

Cattle"—himself a Norfolk man—admits that these owe their origin largely

to the Galloways. He says: "From a very early period large numbers of

polled Galloway cattle were brought into the counties of Norfolk and

Suffolk. There can be little doubt that these were crossed with one or

other (probably both) of the native races, and that thus the present breed

of Norfolk and Suffolk red-polled cattle was called into existence. The

writer is by no means disposed to accept the theory propounded by the

author of the article on 'Scotch Polled Cattle' (in the above work), that

our Norfolk polls are simply red Galloways. True enough, there is a

resemblance between the heads of the two sorts, each being furnished with

a red tuft of hair covering the forehead. In the Norfolk beast this

appendage will, however, be. frequently composed of a mixture of red and

white hair. More rarely a large spot of pure white makes its appearance in

the face. The deep blood-red colour of the Norfolk polls is moreover many

shades darker than we have seen in any specimens of the Galloway breed.

These two peculiarities go far to support the conclusion we have arrived

at—that the old native race had a due share in the concoction of the

present breed." All may be conceded which this writer contends for, and

yet it may be true what we have alleged, that Galloways exercised a

prepondering influence in the formation of the present race of Norfolk and

Suffolk polls. It is well known that the late Lord Panmure, on entering

into possession of his estates in 1791, purchased eight young Galloway

bulls and distributed them through Forfarshire. If the numerous produce of

these eight males had been used for breeding purposes they must have

exercised a great influence in moulding the breed of Angus cattle at an

important period of its history, when it was admittedly in a transition

state. But it has been alleged on what seems good authority, that the

produce of these bulls proving very inferior, none of them were retained

as breeders, and that consequently the step proved a failure. More

recently several well-known breeders of Angus cattle took Galloway cows

and heifers to the north, and tried the experiment of crossing them with

the native bulls. Among these we may specify Betsy (124), which was bred

by Mr James Gillespie, Annanbank, Lockerbie. Mr Cruickshank, Cloves, had a

cow Greed (633), whose dam was Betsy (124), and whose sire was the Angus

bull Vulcan (93). Greed was a first prize winner against pure-bred

Aberdeen cattle, so that in her case the cross seems to have answered.

Then Mr Cruickshank bred from Greed a cow, Lucy of Cloves (635), whose

sire was Willie (91), a bull bred at Tillyfour. Lucy of Cloves—which was

thus three parts Angus and one part Galloway.—took a prominent position in

the prize list as a yearling at both Elgin and Aberdeen, so that the

second cross seems to have been equally successful.

The means that might be used

for the improvement of Galloway Cattle.

While it is undoubted that

the quality of by far the greater number of Galloway cattle is decidedly

better than it was twenty years ago, yet it is asserted by some that there

were individual specimens of the race at that time superior in some

important respects to what even the best are now. Without discussing this

point, it may be freely enough conceded that improvements might be

effected upon them, but it is a difficult question to determine what are

the best means for bringing about that improvement. Of course the

selection of proper sires and dams to breed with is a matter of first

importance, and one which depends upon the skill and judgment of the

breeder; and the record of the pedigrees of all the best animals in the

Herd-Book will afford breeders reliable data to proceed upon in making

that selection. The infusion of the blood of other breeds of cattle into

the Galloways has been and is being tried, but hitherto with indifferent

results. The Duke of Buccleuch has tried one experiment, and his Grace is

in the course of trying another. We may tell the former in his Grace's own

words: "I tried some time ago the experiment of breeding from an Angus cow

and a Galloway bull, but it did not succeed, and I gave it up. I found

that my object, which was to gain size, was defeated, and I lost the

fineness of quality without obtaining the increase in bulk" (speech at

meeting of Galloway Cattle Society at Dumfries, 24th October 1877). The

other experiment which is now being tried at Drumlanrig is an important

and interesting one. There can be no doubt but that there are some points

in which the West Highland cattle excel the Galloways as beef-producing

animals, and in these respects it is obviously desirable that the latter

should be improved up to the standard of the former. With this object Mr

Cranston, manager to his Grace, put a Galloway bull to two West Highland

heifers having the best characteristics of the race, and the calves, both

of which fortunately are heifer ones, are promising youngsters. Other

heifers are this year to be used for a similar purpose. The experiment is

of great importance, and may, if successful, be productive of great

benefit to the breed of Galloway cattle; while if it fails to accomplish

the object in view, no evil results can flow from it. The Council of the

Galloway Cattle Society have resolved to enter the produce of this cross

in an Appendix to the Herd-Book, so that the means of tracing and watching

the success of the experiments will be within the reach of all who are

specially interested in it. The best herds of Galloway cattle are becoming

a good deal in-bred, and it would be of great advantage could some new

blood be infused into them, and at the same time the characteristics of

the breed not deteriorated but rather improved thereby. |