|

By Thomas Wilkie, Forester,

Ardkinglas, Cairadow.

[Premium—Five Sovereigns.]

In reporting upon the

management of plantations, it is necessary to embrace wholly that system

practised by the reporter, and to state whether the chief object of his

management be ornamental or profitable forestry. Both these classes are,

and ever ought to be, adopted on all properties. A desire, however, seems

to exist at the present time to grow a crop of profitable wood upon ground

which is incapable to carry such a crop, but would, in many cases, carry a

few ornamental trees.

The subject of selection of

plants has been largely discussed, and many useful inquiries made thereon.

Some practical men have been successful in this department, while others

have failed, although acting upon the same principle as the former. The

climate, exposure, state, and class of soil, &c, are so varied that one

often finds himself quite baffled, while others tell of their success.

I find that the best guide

for the planter is to study nature, so far as is within our power, for

wherever we find trees growing naturally, we are sure if we plant the same

species on similar soils, temperature, and exposure, that we will be

successful. I quite believe that we are able to beautify many of our

barren-looking spots with plants, though some of them may be, and are,

quite incapable of producing what I may call a remunerative crop Many of

our mossy hags vary so much in depth and kind that it is difficult to

ascertain with perfect accuracy what class of plants is best adapted for

such soils. From a careful selection, however, if moderately well drained,

a sufficient number might grow to have an ornamental appearance. From

severe droughts, late or early frosts, more especially if on a low

elevation Liable to hoar-frost, the plants suffer, languish, and

ultimately die out, while on a higher elevation they might grow quite

well. Damp soils also are incapable of producing a profitable crop of

timber when the water is stagnant on the ground; but if merely percolating

it, there is no fear of many plants dying if they are judiciously

selected. Draining in a plantation ought always to be carried on to such

an extent as to prevent stagnation of the water, otherwise the water

becomes putrid and putrifies the natural sap of the plants, which I

believe to be the cause, combined with atmospheric influences, of

generating those insects which attack the roots and fibres of the plants.

For high elevations, where hard gravelly till abounds, a careful selection

of plants ought to be made. In such cases I would strongly recommend the

hazel and birch to be plentifully distributed among conifers, embracing

the larch and Scotch fir, as they are almost certain to grow, and would

prove an excellent shelter, while acting as nurses for the conifers. These

classes of plants, along with the mountain pine,—Pinus pumilio synmontana,

- should form a good proportion in plantations upon high bare, or

projecting rocks, to which it would be well to add the mountain ash or

rowan tree. These, mixed with a few larches in the richer hollows, would

present a beautiful aspect during the summer season, and the above ground

is only capable of being made ornamental.

The drains in the

plantation ought to be inspected periodically, and if any places are found

where the water is stagnant, it ought to be carried off either by

deepening the existing drains or forming new ones.

Thinning ought to commence

as soon as the branches begin to meet, and the principle on which it ought

to be conducted ever should be, not to allow the trees to touch one

another.

The margins of plantations,

roadsides, the edges of drains, as well as high projections, should be

well thinned out at first thinnings, so as to allow those left to get well

established in the ground. As soon as thinning operations are completed

for the time being, the drains ought to be examined to see if any branches

have been left in them, if so, to get them cleared out. The hardwood trees

ought to be looked at, and if necessary to foreshorten the heavy branches,

and to cut off or foreshorten all double or treble tops, leaving the one

most closely connected with the main stem. In some cases I adopted close

cutting off, in others I preferred to cut only half-way down the double

top. If the main leader is well branched I adopt the former, and if badly

branched, the latter process. I prefer cutting off any double tops of the

conifers, of whatever kind, during the month of September, as they do not

then bleed. No age can be stated at which thinning of plantations ought to

commence, neither when it should be done periodically, as some parts may

require to be twice thinned before other parts require it at all. I find

the principle of not allowing the trees to touch my safest guide in this

matter. It is an object, however, I always adopt, so far as practicable,

to carry up as many plants as the ground will bear till twenty-five or

thirty years of age, as I find the wood about that time very saleable,

being well adapted for pitwood. Previous to thinning a plantation, say

between the ages of twelve and forty years, I go over it a year preceding,

and after selecting I prune all my standards which I intend to leave,

acting upon the principle of balancing the trees as fairly as possible;

foreshorten all heavy branches, as well as those likely to be broken off

by the wind, and cutting off all superfluous and dead branches at the

smallest part or neck of the branch, afterwards dressing with the pruning

knife.

A great deal of damage is

often done to standing trees by dragging, which I think might be easily

avoided, as I find by attending to the following rule that I get scarcely

any damage done:—I cut places at the roadsides for a centre to drag to for

cross-cutting and loading the carts at; I then fell all the trees at an

angle of not more than 35 degrees either up or down hill from the drag

roads, which run straight up and down hill. These roads, as well as the

drains, after the dragging has been completed, should be attended to, as

they naturally gather water in their courses and carry it into the

hollows, which seriously affects standing trees. The water ought to be

carried off to the nearest drains. Another system I always study in

thinning is, when two trees are allowed to grow closely together rather

too long, as they sometimes are, I cut out, if on a westerly exposure, the

one on the east side, as the other is more likely to resist the wind from

the west; if on an easterly exposure, the opposite, and other exposures

similarly. Though all these rules are duly attended to we cannot get every

tree to grow to like proportions, in fact, one forester plants, but seldom

has charge of his plantations till they become of much value, as one man

sows plants and trains, and another cuts, down at his pleasure. However,

the rule for one and all is to leave that class for a permanent crop that

is showing the most vigour in growth, which can easily be seen. If that is

the case, as it ever ought to be, of the forester, he will act wisely. No

demand and no pecuniary objects ever ought to sway him from this rule,

excepting in a case of necessity for the property use.

As a general rule, thinning

operations ought to be finished in a plantation by the time it reaches say

forty-five to fifty years of age, and have the standards only left, none

of which ought to be cut out unless showing symptoms of decay, or in case

of necessity as above.

The plantation, the

management of which is about to be described, is 205 acres in extent;

altitude, 650 feet above sea-level. Exposure on north side to the sea a

mile distant, on east. side being rather sheltered by a ridge running from

top of hill near to north-east corner, south side open, and the west side

somewhat sheltered by a higher hill further west. Soils various, chiefly

mossy loam, with subsoil of porous gravel on the lower portion. In flats

behind rocks of greyish whinstone, which abound on hill-side, and in some

cases are prominent, the soils are mossy loam and virgin soil, subsoil

being of a porous, sandy nature.

The hill is somewhat

conical in shape, with flat on top of black peat, varying in depth from 9

inches to 2½ feet.

The plants were Scotch fir,

larch, spruce, and silver firs, oak, elm, and ash, and were distributed 4

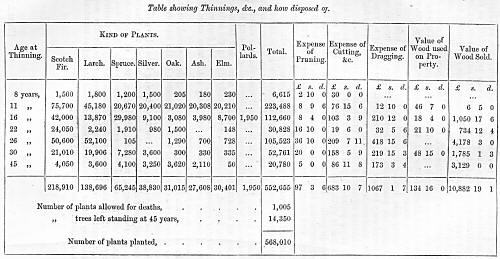

feet apart, as follows:—

The Scotch fir, larch, and

spruce covered the top and down the sides all round to a distance of 150

yards. On the north side were planted Scotch fir, larch, spruce, and

silver firs, with a few oak, elm, and ash, more of the Scotch fir, larch,

elm, and ash than of the other plants; on the east side were the Scotch

fir, larch, spruce, and ash only; on the south side larch, oak, spruce,

and silver firs; on the west side a mixture of all the above-named plants.

Age at first thinning, eight years.

Measurement of Scotch firs

on tops being 4½ feet in height and 4½ inches in girth at a foot from

ground. Larch and spruce 5½ feet in height and 5 inches in girth. On the

hill-sides all round, the average of Scotch fir being 6 feet in height and

5½ inches in girth; larch and silver firs, 7 feet in height and 6 inches

in girth ; spruce, 6 feet in height and 5½ inches in girth. The oak, elm,

and ash averaged in height 5½ feet, and in girth 4½ inches. The probable

expense of plants, planting, and keeping of same from time of planting to

this date might be stated at £2100.

At this age (eight years) I

observed that the larch and silver firs, together with the ash and elm, on

north side showed signs of most rapid growth; on the east side the larch,

elm, and ash ; on the south and west sides larch, silver firs, and oak. On

the lower section the plants were touching each other. I therefore

commenced thinning operations, endeavouring to relieve those showing signs

of most rapid growth, studying always to take out those post drawn up and

void of branches, strictly adhering to this rule on the north side, it

being exposed to the sea. The plants higher up the hill having still

plenty of room, I resolved not to touch them till three years later. After

the thinning operation was completed I went over the whole plantation,

relieving the main leaders, and foreshortening all heavy lateral branches

of the hardwoods, acting upon the principle already advanced. The

thinnings of the larger larch trees were used for protecting trees which

had been planted singly, and repairing fences round cottagers' gardens,

&c, the remainder being granted to tenants and cottagers on the

understanding that they carried them out of the plantation, stem and

branches entire without pruning.

Three years later I found

fir trees on lower section to gain 3 feet 6inches in height, hardwoods 2½

feet and girth in proportion; on higher sections and hollows on top had

grown 2½ feet, and increased in girth 2½ inches. They required to be

thinned, and I did so, acting upon the principles already adverted to. The

thinnings were disposed of by converting the larch into stabs for repair

of fences and sheep net stakes, and the hard-wood's for fuel wood, which

cost and realised as on table annexed. The remainder were granted, as in

former case, to cottagers, &c.

At sixteen years of age the

conifers on an average were 16 feet in height and 14½ inches in girth,

hardwoods 13 feet in height and 9½ inches in girth. I selected, pruned,

and foreshortened all standard hardwood trees. I again thinned out on

former principles, leaving upon the high tops Scotch firs mostly, as most

likely to resist the exposure, and upon projecting rocks and ridges the

oak and Scotch fir, still studying to leave those trees maintaining the

healthiest appearance and showing signs of most rapid growth. As thinning

was proceeded with I made pollards of a sufficient number of hardwoods

nearest to the margin of the plantation, with the intention to transplant

them the following year into the line of fence to act as stabs. The

thinnings of a few of the larches were used as stabs until the pollards

got established in soil, and the remainder disposed of by sale to a wood

merchant. The cost and realisation of this thinning is also shown in table

annexed.

At twenty-two years of age

I found the conifers avenged 23½ feet in height and 20 inches in girth,

the hardwoods 19 feet and 15½ inches. A good many trees on the higher

portion being unsuitable for pitwood. At this time I only took out those

trees actually necessary with a view to allow the others to grow to a

sufficient size for pitwood; because if there are many! trees that will

not measure 3 inches diameter at 15 feet in length, the value is

considerably reduced. Those suitable for pitwood were sold, and the

smaller trees were used for estate purposes.

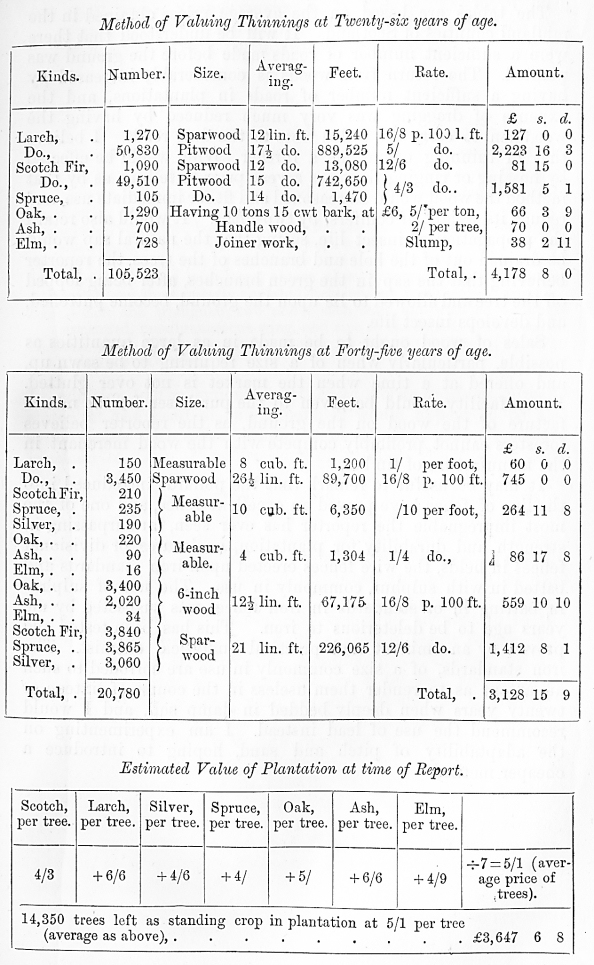

At twenty-six years of age

I found the conifers 28 1/6 feet in height and 23½ inches in girth, the

hardwoods 23 feet in height and 20 inches in girth. Having the previous

year gone over the plantation and foreshortened all heavy branches and

double tops, knowing by experience and from observation that hardwoods

about this age are apt to become hidebound when severely thinned or

pruned; because when they are severely thinned they are left more exposed

to the atmosphere, and when pruned too much they are deprived of part of

their respirative organs, both these causes having a tendency to produce

young shoots from the bole of the tree, so that instead of reaping a

benefit from either, they are retarded in their growth. I commenced

thinning at the margin of the wood, acting upon the principles adverted

to, viz., of not allowing the trees to touch; but on coming to the tops of

projecting rocks and high ridges to prevent the conifers being too much

drawn up, I endeavoured to select the best branched ones to stand, because

if allowed to get overmuch drawn up they are apt to be blown down. I found

the Scotch fir and oak on these ridges growing well, and gave them plenty

of room for the above reason.

The elm and ash on the

lower portion, both on north and east sides, as well as the larch,

surpassed the others in growth.

These I endeavoured to

relieve. The oak, silver firs, and larch on the better soils were doing

well. The oak particularly so on the southern exposure, it being partial

to the sunny side, unless openly exposed to the sea. The thinnings were

cut, pruned, and dragged by men and horses on the estate during the autumn

and winter, excepting the oak, which were allowed to stand in order that

they might be peeled during the summer. The whole was sold the March

following, the drains being scoured out, as well as the water cut off the

drag roads.

A heavy gale having

occurred in the autumn, I went carefully over the plantation to see what

damage had been done, and found only twenty trees blown down, and scarcely

a branch of the hardwoods broken. The oaks and conifers on the high ridges

having afforded a perfect protection on either side.

At thirty years of age I

found conifers 33½ feet in height and 30 inches in girth, and the

hardwoods 28 feet in height and 24 inches in girth. I went over the

plantation, thinning out those trees beginning to press upon the

hardwoods, these being cut, lopped, and dragged as formerly. The hardwoods

were used for estate purposes, and the conifers sold. I went over the

drains and drag roads, giving them the necessary repair.

At forty-five years of age

the conifers were 48½ feet in height and 43 inches in girth, the hardwoods

43 feet in height and 38 inches in girth. Believing it to be full time

that the standards only should be left in the wood, I cut down all

excepting them, leaving on an average seventy trees per acre. The

thinnings were cut, lopped, and dragged as formerly during the autumn and

winter seasons, and sold. The heavy-branched hardwoods were lightened, and

the drains and drag roads were carefully gone over as on former occasions.

In the March following

rather a severe gale occurred, but no trees were blown down, and scarcely

a branch of the hardwoods were broken.

I attribute the cause of so

few trees having been blown down to the early as well as the more remote

thinnings of the plantation on the margin, roadsides, drainsides, tops of

projecting rocks, high ridges, and thin soils, the hardwoods having been

early and frequently pruned, as was found necessary, and conifers on

projecting rocks having established themselves in the soil, presenting

rather a bushy appearance, and serving as an excellent shelter to the main

body of the plantation.

The tables are based on the

average prices obtained in the midland counties of Scotland. It will be

understood that there were a sufficient number of roads made before the

ground was planted. The return from woods is considerably increased by

having a sufficient number of roads in plantations, and the expense of

dragging was very much reduced by having the woodmen to carry the felled

trees to the drag roads. I believe that in thinning operations a further

saving would be effected by hoseing or ringing the trees a year prior to

felling, as by that method the wood would be seasoned and fit for

immediate use, and reduce its weight, if conifers, by two-fifths. It would

also retard the propagation of insect life, seeing that the natural sap

would be drained out of the bole and branches of the trees, the reporter

believing that the sap in the green branches, after being lopped off the

tree and allowed to lie upon the ground, become putrefied, and develops

insect life.

Sales of wood ought to be

made in as large quantities as possible, particularly when of a size

requiring to be sawn up, and offered at a time when the market is not over

glutted. Every facility should be given to the purchaser for the

manufacture of the wood on the ground, as the reporter believes foresters

cannot profitably compete with the wood merchant in the manufacture of

timber.

It may be useful to remark

that the pollards introduced into the line of fence have proved an

excellent fence, and one of the most impregnable the reporter has ever

seen, far surpassing in strength and durability for plantation,

enclosures, or divisional fences in fields, the wire fences erected upon

iron standards and batted in with sulphur, commonly in use. The use of

sulphur in batting in of standards in iron fences was suspected by me

years ago to be deleterious to iron. This has been tested and proved by an

eminent and practical analytical chemist. The iron standards, of a size

commonly in use are corroded to such an extent as to render them useless

in the course of sixteen or twenty years when deeply bedded in damp soil,

and I would recommend the use of lead instead. I am experimenting on the

adaptability of pitch and sand, hoping to introduce a cheaper method. |