|

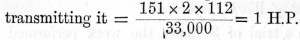

I. Fisken Steam Cultivating

Machinery.

In 1871, the Fisken Steam

Cultivating Machinery was tried at the late Marquis of Tweeddale's home

farm at Yester, and at Offerton Hall, near Sunderland. Both of these

trials were attended by members of the Highland Society's Committee on

Machinery, and reports of the observations then made will be found in the

4th volume of the Society's Transactions by Professor Wilson, Mr Swinton,

Holyn Bank, and the late Professor Rankine, then consulting engineer to

the Society.

On perusing these reports,

it will be found that circumstances prevented a full investigation being

made, and that, while some defects in the machinery for conveying the

power from the engine to the plough were noticed, there was nevertheless a

general expression of opinion that the apparatus was admirably suited to

perform the work required of it.

Since 1871 Messrs Fisken

have improved their apparatus so much as to warrant them in applying to

the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council for an extension of their

patent, which was granted in March, 1876, for a period of six years. On

the same •grounds they exhibited a model of their apparatus, as now

improved at the Society's Show in July last, at Aberdeen, and the

Implement Committee, on consideration, recommended it for trial.

In accordance with this

recommendation, the Fisken apparatus was subjected to a series of trials,

beginning on Tuesday the 14th, and terminating on the 18th November, on

the farm of Liberton Tower Mains, the use of the ground and all facilities

for making the trials having been kindly afforded by Mr Bryden Monteith,

one of the directors of the Society. Thereafter, further opportunities

occurred for testing the "System" on the farms of Mr Black at Liberton

Mains, and Mr Gray at Southfield, both of these gentlemen having kindly

given the Society the means of prosecuting their experimental inquiries.

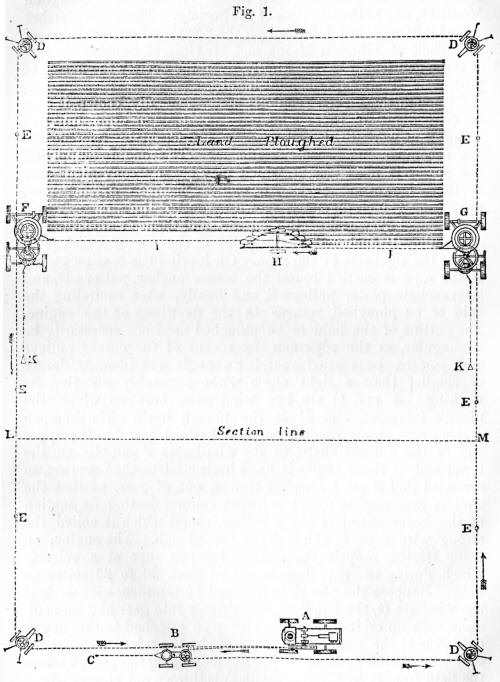

Although the Fisken Tackle

is pretty generally known, it may be convenient for those who have not had

an opportunity of seeing it at work to describe, briefly, its action by

reference to the accompanying wood-cut (fig. .1). The engine supplying the

power is placed at A, which may be any convenient spot at the edge of a

field. An endless hempen driving rope, measuring ¾ inch diameter, shown by

dotted lines, passes round the grooved fly-wheel of the engine, and thence

round the tension pulley B anchored at the point C, the use of which is to

adjust the tightness of the rope. On leaving the tension pulley B, the

rope is carried round the corner anchor, pulleys I), and intermediate

porter pulleys E, and finally, after encircling the field to be ploughed,

returns to the fly-wheel of the engine. The outline of the field to be

ploughed need not necessarily be rectangular, as the rope can, by means of

the corner pulleys and porters, be carried round an angle considerably

larger or smaller than a right angle without notably affecting its

working. F and G are two windlasses, between which the plough traverses,

and H is the plough itself. The hempen driving-rope passes round a

horizontal wheel, keyed to the upper end of the upright shafts of the

windlasses F and G. On the lower end of these shafts is fixed horizontal

toothed gearing, so arranged that it can be readily thrown out of gear, so

that the endless rope may be driven without communicating its motion to

the lower barrel of the windlass, round which is coiled the strong wire

rope I which drags the plough. The engine, on being started, propels the

endless hempen rope at a velocity which, during the experiments, varied

from 20 to 25 miles an hour. Suppose the plough is required to commence

its work at the windlass G, the windlass F is thrown into gear and

immediately coils up on its barrel the wire rope attached to the plough

(which is at the same time given off by the windlass G) at the easy rate

of about two miles per hour, dragging the plough across the field from G

to F. The windlass is thrown out of gear whenever the plough reaches F.

The plough is reset for another furrow,—an operation which in ordinary

working was found to occupy about half a minute,—the two windlasses are

moved forward a few feet by machinery worked by the endless rope winding

up a rope anchored at K, and the opposite windlass G being then thrown

into gear, the plough is drawn slowly back to

its starting point, so that

it will be understood that the engine never requires to reverse or stop

its motion, the endless rope continues to haul, and the action of the

windlass in starting and stopping the plough and its consequent

reciprocatory action all go on without involving the necessity of any

signals between the man working the plough and the man working the engine.

The mechanism of the windlasses for regulating the movement of the plough,

as well as that for moving them forward as the ploughing proceeds, is

ingenious; but it is not possible, without reference to enlarged diagrams,

to describe the various devices which the patentees have introduced in

their endeavours to perfect their system.

The advantages claimed for

the system by the patentees may be shortly stated, as follows:—-

1st. The transmission of

power from the engine by means of the fast travelling, light hempen

endless rope.

2d. By the use of their

windlasses, the fast motion of the endless rope can be applied to the slow

motion required for the plough at any part of the field without stopping

the engine.

3d. The use of one engine

(and that may be any traction or portable engine of the ordinary type).

4th. The circumstance that

the engine does not require to traverse the field to be ploughed, thus

avoiding the risk of breaking drain tile pipes.

5th. The facility with

which the power can be transmitted by the travelling rope enables the

engine to be placed in a situation most convenient for the supply of water

and fuel, the carts supplying which do not require to enter the field, the

position of the engine being stationary.

6th. The small quantity of

land left in headlands, the breadth of which averages 14 feet.

In stating what have been

represented as the points of superiority claimed for Fisken's Tackle, the

Committee must point out that the trial now to be reported on was not of a

competitive character, there being no competitive system of steam

ploughing with which to compare it, and therefore, in giving their report,

they must confine themselves strictly to the result of the investigation

now made on Fisken's Tackle as represented in the model shown at Aberdeen.

At the same time, they have to notice that the results of the present

trials, though not embracing other systems of steam ploughing, and,

therefore, not competitive, will nevertheless be useful should it be

necessary hereafter to compare them with trials made on any other steam

ploughing apparatus. Indeed, it seems doubtful whether two systems of

steam cultivation could have been simultaneously considered at one

competition in a satisfactory manner.

"With these preliminary

observations, the Committee proceed to give the following results of the

various observations made, and the conclusions they have deduced from

them.

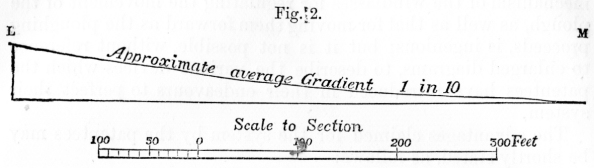

The field selected for the

trials on Mr. Monteith's farm has a surface which, according to the

section fig. 2, has an average

gradient of about 1 in 10,

which was considered not unfavourable to obtaining a fair working trial of

the powers of the tackle. (The position of the section L M is shown in

Fig. 1.) The field was in stubble, with a very liberal allowance of

farm-yard manure spread on it. The soil may be called light and free from

stones. The weather throughout the whole of the trial was wet and very

foggy, but not so wet as to interfere with the proper working of the

apparatus.

Engine.

The engine used during the

experiments was one of Robey's patent traction engines, 10 H.P. (nominal),

weighing 10 tons 10 cwt.

During the trials the

fly-wheel averaged 140 revolutions per minute, giving an average speed to

the driving rope of 22 miles per hour.

Plough.

The plough was Fisken's

patent three-furrow plough, weighing 25 cwt., and cutting three furrows 8½

inches deep by 11 inches wide.

Dynamometer.

The dynamometer used in

making the trials was that of Messrs Easton & Amos.

Draught of Plough and

Tackle.

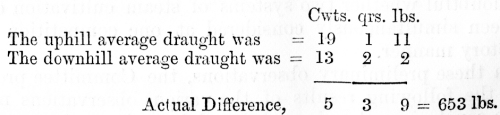

The theoretical difference

of draught between the up and down trials, due to gravity, may be taken as

follows:—

We may therefore safely

assume the average draught on level ground, with an 8½ inch furrow in

light soil, at 16 cwt.; and the correctness of this result deduced from

trials on the sloping field was confirmed by trials made subsequently on a

field that was nearly level.

Horse Power.

In order to determine the

horse-power, the following observation were made simultaneously with those

above given for the draught:—

Uphill average velocity was

127½ ft. per minute, which gives 8.37 H.P. Downhill average velocity was

175 ft. per minute, which gives 8.02 H.P. So that the average horse-power

may be stated at 8.2.

Draught of Tackle.

The dynamometer having been

placed so as to occupy the position of the plough, it was found that the

strain produced by the carrying rope, 1000 yards in length, and the two

windlasses, was 2 cwt., the dynamometer moving at the rate of 151 feet per

minute, and hence loss of power due to the Fisken mode of

Removals.

From the description of the

apparatus given at page 2, it will be seen that the proper arrangement of

the corner anchors, porters, &c, which is a feature peculiar to the Fisken

tackle, is not a work which can be done by the ordinary run of

farm-servants without instruction. It is also an operation occupying some

time, for which an allowance must be made in calculating the cost of work

done. The Committee had only one opportunity of ascertaining the time

taken to set up the tackle, and it was found to be two hours, but this was

under the direction of Mr Fisken's able assistants, and the Committee can

hardly arrive at any reliable result from that single trial. They have,

therefore, no alternative but to adopt Messrs Fisken's estimate of the

cost of "removals" at two shillings per day.

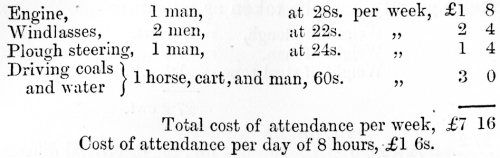

Attendance and Wages.

Consumpt of Coal, Water, &c.

On a trial extending over a

period of 3 hours, it was found that the consumpt of water was equal to

1099 gallons per day of 8 hours; and the consumpt of coal for the same

period was found to be 14½ cwt., which, at 9d. per cwt. = 10s. 10½d. per

day of 8 hours.

Assuming a working day at 8

hours, we obtain from the above data the following as the cost:—

Cost of Work Performed.

It was found that on a

trial of 3 hours, the work performed was 2a. 96p., which amounts to 6 a.

149 P. per day of 8 hours. But as the amount of work during the trials

could not be kept up during a whole day, it cannot safely be used as a

fair criterion, and we are disposed to think that the actual amount of

ordinary work done would not exceed 6 acres in a day of 8 hours, which, at

L.2, 17s. 4½d. per day is 9s. 6¾d. per acre.

The Committee are aware

that doubts have been expressed as to the durability of the working

tackle, a subject on which they have no personal experience to guide them.

They have, however, no hesitation in saying that the tackle is simple in

its construction, and not, in their opinion, liable to failure. But as the

opinions of those who have used the apparatus may be reckoned of some

weight, they quote a few opinions on this point from Messrs Fisken's

published notice of their patent. Mr Ingleton, of Minster, Sheerness,

says, "The windlasses are practically as good as when they left your shop

four years since." Mr Finn of Black Friars, Canterbury, writing in 1874,

says, " We had out set of Fisken's tackle in December 1871, and have

ploughed 978 acres with it, and are still using the rope which came with

it;" and Mr Fenigan of Talacre, North Wales, in giving evidence before the

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, states that " he had cultivated

1200 acres without a shilling of expense having been incurred in the

repair of the windlass, and the tackle was still in good order, working

every day."

In addition to the trials,

the results of which have been described, the Fisken tackle was, as

already stated, employed in farms in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh, and

the gentlemen by whom it was so employed having been asked to give their

opinion of the manner in which it performed its work, the following

letters have been received: —

"Liberton Tower Mains,

"December 5th, 1876.

"Dear Sir,—Yours of 2d

instant to hand. My opinion of the work done on my farm by the Fisken

plough is very favourable; the land was well ploughed, square taken out

and laid properly back. I don't think it better than horse ploughing ; it

had this on my land to recommend it, viz., the bank being steep, it had

more power than horses. I tried several at 12 inches ; it did it as well

as at 9 and 10 inches. A 12 inch furrow on my land would have required

three horses. The plough could be so set as to plough any kind of

furrow.—I am, very truly yours,

David Stevenson, Esq., C.E.

(Signed) "Bryden Monteith."

"Southfield, Edinburgh, 2d

December 1876.

"Dear Sir,—I am duly

favoured with your letter of this date, asking my opinion regarding the

working of the Fisken tackle.

"In reply, allow me to say

that I am very much pleased with the work performed, and I am of opinion

that it is superior to horse ploughing, and leaves the land in a better

state for spring cultivation : and I may also state that all the practical

farmers who had the opportunity of seeing here the work, and the working

of the tackle, were highly satisfied. I may mention that in my field some

boulders were met with, which will require to be all taken out, to save

breakage and detention, and ensure successful working.

"In confirmation of my

decided opinion in favour of the system, I have purchased the engine and

tackle at present on my farm.—I am, yours very truly,

David Stevenson, Esq., C.E.

(Signed) " William Gray."

Liberton Mains, Edinburgh,

22d December 1876.

"Dear Sir,—I am sorry I

have been so long in answering your note about Fisken's plough, but the

reason is partly that I cannot say anything in praise of the work it did

for me. I am very sorry, for I think very highly of the tackle, and have

no doubt it will come into general use; but there is one thing certain, it

cannot plough lea. The mild growing weather we have had has made my field

ploughed by it look quite green, whereas the land ploughed by my own

ploughs looks quite like winter.—I am, yours truly,

"David Stevenson, Esq., C.E.

"Robert Black."

Two distinct questions

arise in the investigation of steam tillage—First, What is the best

apparatus for transmitting motion to the plough ? Second, Which is the

best construction of plough for doing the work required.

The Committee's attention

has been confined to the first, and, perhaps it may be added, the most

important of these inquiries, for if it can be determined which is the

most convenient and economical apparatus that can be used for steam

tillage, the form of plough best adapted for particular soils may be

matter for further investigation.

The perfect disintegration

of the soil, so as to approach as nearly as possible to the action of

manual spade-work, is the aim to be reached, and that must obviously

depend on the kind of soil to be ploughed, whether clay or loam, for

example, and hence the necessity of adapting the plough to the soil; and

probably manufacturers may with advantage turn their attention to a still

more perfect and easy means of adjusting the coulters and shares and

mould-boards to the varying soils in which they have to work. This may in

some measure account for the difference of opinion in the foregoing

letters, though all of the writers, it will be remarked, give testimony to

the satisfactory working of the tackle itself.

After duly considering all

the information that has been brought before them, the Committee have to

report that the Fisken steam cultivation tackle is based on the ingenious

conception of communicating power to great distances, by means of a

rapidly moving light rope; that the mechanical arrangements for carrying

out the conception and applying the rapid motion of the travelling rope to

the slow motion of the plough, as recently improved, are well designed,

and that the "tackle" performs its work in all respects satisfactorily.

The Committee recommend

that the Society should award to Messrs Fisken a premium of fifty guineas.

Having laid before the

Society the result of their investigations, the Committee cannot close

this report without repeating that the favourable opinions they have

expressed of the Fisken tackle must not be held as warranting a conclusion

in favour of that system as the best that has been devised for steam

culture. From what has already been stated, it will be seen that such a

conclusion would be altogether premature. Some members of the Committee

are well aware of the amount and excellence of work performed by Fowler's

improved steam tackle, and it is well known that there are machines by

other makers equally worthy of attention. It is obvious, therefore, that

until these other "systems" (for so they have been called) have been

subjected to trials similar to those which the Committee have conducted,

no opinion as to the comparative merits of the different systems of

working can be arrived at.

It cannot be questioned

that those whose duty it is to encourage any branch of scientific or

practical research cannot at the present day afford to remain passive or

inactive. New views, followed by new results, are yearly brought forward

in every department of study, and whether such views be sound or false,

they claim, and should receive full consideration. To this agriculture is

no exception. The wide range of subjects embraced in its now acknowledged

proper study includes, in those who seek the Society's diplomas and

certificates, some popular knowledge of chemistry, natural history,

veterinary surgery, botany, and engineering, and thus the Society

acknowledges the general onward movement for inquiry, and while it may be

a subject for difference of opinion in what may and to what extent the

Society can best promote the dissemination of knowledge in some of those

branches of study, it appears to the Committee that, as regards the

construction and utility of new agricultural implements, no such

difficulty exists. The appeal to a properly conducted trial is available,

and the Committee regard it as a highly important function of the Highland

Society to procure and supply to its members the best possible information

on the merits of the different implements annually brought forward as new

inventions, many of which have undoubtedly no good qualities to commend

them.

The application of

steam-power to the tillage of the soil is pre-eminently one of those

subjects which, from its importance, the Committee think should be fully

investigated, in order that agriculturists may be provided with

authoritative data for their guidance in selecting the implements they

employ; and following-out this view, they are of opinion that every

inventor who claims superiority for his system of steam tillage should be

encouraged by the Society to submit it to a trial similar to that afforded

by Messrs Fisken, who, the Committee think, deserve the special thanks of

the Society for the personal trouble they have taken in submitting their

invention so fully and unreservedly for examination by the Society's

Committee.

The Board approved of the

report.

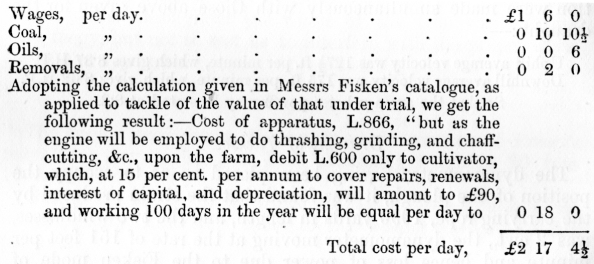

II.—Robey & Co.'s Thrashing

Machine.

This machine (fig. 3) was

exhibited by Messrs Robey & Co., Lincoln, and was tried with barley on the

15th, 16th, and 17th November at Mr Monteith's farm, Liberton Tower Mains.

It is said to be of new design, and to embrace many improvements, chiefly

the reduction of the weights of the shoes and riddles, and having enlarged

bearings for the spindles. The lower part of the framework is also left

open, so as to show the working parts, which is an advantage in regard to

attention. The patent self-feeding apparatus consists of a covered hopper

on the top of the thrashing machine, containing a shaking-board, on which

the crop falls as it is filled in, and means of adjustment are provided to

regulate the quantity of feed. There is a lever close to the attendant, so

that the machine can be quickly stopped if required. The price of the

machine is L.160. The machine was driven by one of Robey & Co.'s six

horse-power traction engines, and the quantity of grain finished for the

market per hour was six quarters. The Committee consider that the work

done was most satisfactorily performed; that the various improvements

which have been introduced, especially the new feeding apparatus, are most

ingenious and likely to be useful, and think it worthy of the Society's

gold medal. The report was approved.

III.—Koldmoos' Weed

Eradicator.

The weeding machine

invented by Mr Ingermann of Koldmoos, near Gravenstein, and for three

years well known in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, called "The Koldmoos

Weed Eradicate," and exhibited by Messrs Ord & Maddison Darlington, was

selected for trial by the Implement Committee at the Society's show at

Glasgow in 1875, and the trial took place on Thursday 15th June, 1876, on

the farm of Craigmillar, near Edinburgh. The trial was mads on a field of

barley which had attained the growth of from six to ten inches. The field

was covered with a strong growth of mustard in flower; the ground on the

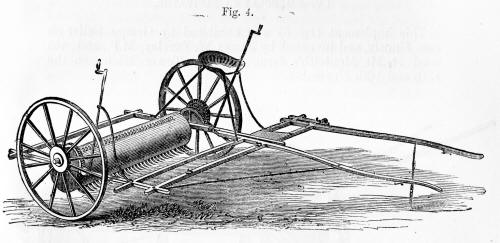

day of trial was rather dry. The machine (fig. 4) takes in a breadth of

four feet six inches, and was very easily drawn at a quick pace by one

horse. It consists of a horizontal drum revolving between the carrying

wheels. The periphery of this drum is pierced throughout its whole length

by thin slits, from which, by a simple eccentric arrangement, moved by the

rotation of the drum, three toothed comb cutters are alternately projected

about two and a half inches, and again withdrawn within the drum. The

maximum projection of the comb beyond the periphery of the drum occurs

during the under half of its rotation, when the

combs are in contact with

the corn and weeds. The weeds are thus caught between the teeth of the

comb, and are either pulled up by the roots, or, if too firmly planted,

their upper portions are pulled off. As the d rum revolves, the combs

carrying with them the weeds they have entangled, are gradually withdrawn

into the slits, leaving the weeds they have taken up to be thrown off by

the revolution of the drum. The comb having reached the highest part of

the drum's revolution, and having thrown off all the cut weeds, is again

gradually protruded, and prepared for making another cut in the lower half

of its revolution. The revolution is rapid, and the cutting action of the

blades almost continuous. The Committee are satisfied that the machine did

useful work in removing the mustard while in flower, so as to prevent its

seeding, and that many of the weeds were uprooted. It is possible that in

practice a more favourable state of the ground and growth of the weeds

could be selected for using the implement, so that a greater number of the

weeds might be pulled up. We have to report an important fact—that the

barley received almost no injury by the working of the machine. The

Committee again inspected the field on the 22nd of June, when they found

that the weeds had been very thoroughly eradicated from that portion of

the field on which the machine had been employed. The Committee have no

hesitation in reporting that the machine invented by Mr Ingermann did its

work well, and that it may be usefully employed in all cases where fields

are overrun with weeds; and they recommend that the Society's medium gold

medal should be awarded to Mr Ingermann. This report was approved.

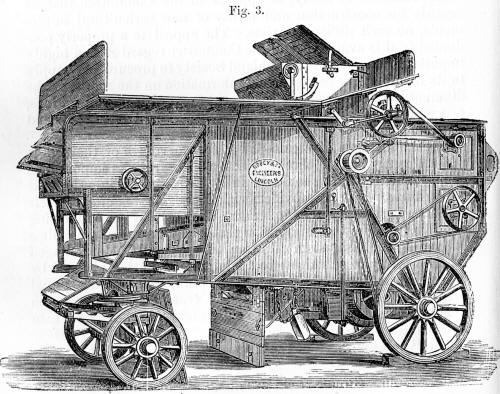

IV.—Barclay's Cultivator.

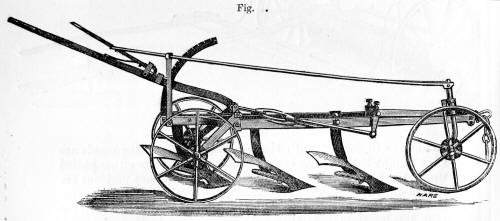

This implement (fig. 5) was

exhibited by George Sellar & Son, Huntly, and invented by James W.

Barclay, M.P., and was tried at Mr Monteith's farm, Liberton Tower Mains,

on the 15th and 16th November.

The objects sought to be

accomplished by the digger are in the case of stubble land to open and

pulverise the soil more effectually to the depth required; to cut the

roots of thistles and other deep-rooted weeds; to turn over the upper two

or three inches of the soil so as to cover the stubble, expose the roots

of weeds to the winter's frost, and to bring up and mix a portion of the

subsoil with the upper mould. The effects to be produced are thus a

combination of the work of the plough and the cultivator. In the case of

green crop land for a seed furrow the objects are to stir and pulverise

the earth, without exposing the dung or leaving the soil so open as after

the ordinary plough, and in the case of both stubble and clean land, to

avoid the packing of the subsoil and consequent separation from the upper

soil caused by the horses' feet on the furrow and by the sole of the

plough. The digger was first tried in a stubble field, making two furrows

nine inches deep. The average draught was about 6 cwt. The Committee

recommended the Directors to award the silver medal. The Board approved of

the award.

V.—Potato Planters.

The Potato Planters

selected at the Glasgow Show 1875 were tried at Liberton Mains, 4th April

1876. The trial had been arranged to take place on a field at Powburn

belonging to Mr Bryden Monteith, but owing to Mr Monteith's unavoidable

absence the arrangements had not been completed, and the Society, after

making a commencement there, was very much indebted to Mr Black, Liberton

Mains, who most kindly offered to have the trial on a field which he was

planting, and to furnish seed, horses and everything that was required.

Six machines appeared on the ground, exhibited by—1. William Dewar, Kellas,

Dundee; 2. Alexander Guthrie, Craigo, Montrose; 3. Charles Hay, North

Merchiston, Edinburgh; 4. G. W. Murray &' Co., Banff (Ferguson's patent);

5 and 6. J. W. Robinson & Co., Liverpool (Aspinwall's patent). The

Committee are glad to report generally that the machines were greatly

improved since the trial in October last; and, with the exception of

Aspinwall's machine, which appeared for the first time, they attribute

that improvement very much to the trial formerly held. They believe that

all the machines would have done their work well with whole seed riddled

to one size; but on this occasion they were put to a thorough test, being

tried with seeds of all sizes, both cut and uncut. One of Aspinwall's

patent machines being adapted solely for planting potatoes on the flat,

not usually done in Scotland, and being of the same principle in the

delivery of the seed as his other machine, it was not tried. After a

thorough trial your committee selected three machines— viz., Mr Guthrie's,

price L.14; Messrs Murray & Co.'s, L.18, 18s.; Aspinwall's patent,

L.12—and again subjected them to a further trial, each machine being drawn

by the same horse. Messrs Guthrie and Murray & Co.'s machines are adapted

to plant two drills, and are on much the same principle, the seed being

raised from a hopper in cups, and dropped into the drilL Both machines are

simple in construction, and not likely to go out of order, and appeared to

be of much the same draught;— Messrs Murray's having this objection, that

the horse and the wheels of the machine travel on the tops of the drills,

which breaks down the drills, and makes the labour of the horse more

severe. Aspinwall's patent plants only one drill, but is very light in

draught; by a very ingenious invention the potato-seed is picked up by a

series of steel needles fixed on a revolving disc, which lift it from the

hopper and drop it in the bottom of the drill. It is simple in

construction, and appears unlikely to be easily put out of order. Your

Committee do not consider that any of these machines are thoroughly

perfect, but at the same time the improvement is so marked, and the work

really so fairly done, that they deem it right to recommend the Directors

to award two prizes of, say, L.10 each to one of the double-drill machines

constructed on the cup principle, and to the single-drill machine

constructed on the needle principle. Your Committee had considerable

difficulty in deciding which of the two machines on the cup principle was

the best, but came to the conclusion that, taking the difference in price

of the machine and everything else into consideration, they were justified

in giving the preference to Mr Guthrie's machine. They would therefore

recommend to the Directors to award a L.10 prize to Mr Alexander Guthrie,

Craigo, Montrose, for double-drill potato-planter on the cup principle,

and a similar prize of L.10 to Messrs J. W. Robertson & Co., Liverpool,

for Aspinwall's patent single-drill potato-planter on the needle

principle.

The following letter on the

subject was then read:—

Banff Foundry, N.B., 10th

April 1876.

Dear Sir,—I have read with

much interest the account of the trial of potato planters held at Liberton,

under the auspices of your Society, as given in the Scotsman and North

British Agriculturist, and as I observe the decision has to be confirmed

by your Directors, I take the liberty of officially addressing you, not

with a view of pronouncing dissatisfaction with the judgment, but in order

to direct the attention of your board of practical agriculturists to some

points of great importance, which I consider your judges will even agree

with me in saying are worth reconsideration. From the accounts given in

the papers named, I learn that the machine forwarded by my firm did as

good work as any, and was only thrown out because the horse had to walk

and the wheels to run on the top of the drills. The first thing I would

respectfully ask your board to consider is, should a potato-planter run in

the bottom of the furrow or on the drill-top? Personally, I was so

satisfied that it should run on the top that I incurred an extra expense

of L.3, 3s. in the price of the machine to secure this ; and can at once

supply the same machine to run in the furrows at L.3, 3s. less money. But

a furrow-running machine, when farmyard dung is used, which is the case in

four instances out of five, has this disadvantage, that the dung is very

much displaced by the horse's feet, and the wheels clogging and collecting

it in hillocks, leaving parts without and parts with excess of dung, so

that the plough following cannot properly cover the same. This

displacement of the dung also tends to displace the seed, even to such an

extent as many remain exposed to the ravages of the crows. On the other

hand, when farmyard dung is used, and the horse made to walk and the

wheels to run on the tops of the drills, the dung is left even and

undisturbed, and from its open nature tends to prevent the seed from

rolling when it falls. Our machine was specially made for this class of

work, and, through no dung being used at the trial, the seeds in our case

had so much further to fall which would tend to make them roll and lie

over irregular. The only drawback to the horse and machine on the top of

the drills is a little extra draught, but this a mere trifle, as the

draught is below 2 cwt., which is nothing to touch any horse. I am quite

aware of the disadvantages that judges are placed at in seeing a lot of

new inventions tried for the first time and under one condition only—viz.,

without farmyard dung. This, I hope, will be considered sufficient excuse

for my addressing you on the subject, and pointing out my reasons for

constructing our machine in the way that it is—more so when I find that

what I consider to be one of the principal points of merit is the very one

that threw it out. I may add, that I have been offered £2 more for my

artificial manure-sowers if I would carry out the same improvement on

them. From the high standing and undoubted integrity of the gentlemen you

had acting as judges, I feel sure they will never suppose that my remarks

are meant to throw any reflection on what is reported to be their opinion,

as I feel sure their purpose is the same as mine—trying to bring to the

front the best machine for the general public, which I hold to be the one

most suitable for the work under all ordinary circumstances.—Yours

faithfully,

(Addressed) F. N. Menzies,

Esq. (Signed) G. W. Murray.

After some discussion, it

was moved that the report of the Committee be approved, and that Mr Murray

be informed that the statements in his letter should have been made by his

representative at the trial; which was unanimously agreed to.

VI.—Potato Lifters.

The trial of the Society's

lifters selected at the Aberdeen Show, 1876, took place on the 10th of

October, in a field on the farm of Liberton Mains, kindly granted for the

purpose by Mr Robert Black. The field was not in the most favourable

condition for the trial: the ground was wet, and the potato shaws were

strong and rank; but potato-lifting was being carried on in the field with

the pronged plough, and it may therefore be considered as perhaps a fair

average field in ordinary farm work, and the Committee give the results of

the trial as they found them:—

1. Messrs Bisset & Sons,

Blairgowrie.—This implement was exhibited at the Aberdeen Show. The

mechanical contrivance by which the potatoes are unearthed does not

materially differ from implements already in use. A deep-cutting broad

cutter raises the plant, and a rapidly revolving wheel, with projecting

arms, scatters the shaws and surrounding earth, and is supposed to throw

out the tubers so as to be ready for being lifted. This operation the

machine certainly performed, but the Committee did not fail to observe

that a considerable number of the potatoes were fairly severed in two

pieces; and when they consider how many more, without having been cut or

severed, must necessarily have been bruised, they are led to the

conclusion that the action of this machine cannot be conducive to the

preservation of potatoes to be stored in pits. Seeing that the mechanical

arrangement is, in principle, the same as that already employed in other

machines, and that the improvement in detail still leaves the machine open

to the objection of injury to the tubers, to which the Committee have

alluded, they do not think it can be reported to have earned a prize.

2. Aspinwall's Patent,

exhibited by Messrs J. W. Robinson & Co., Liverpool.—These exhibitors had

two implements on the ground. The first was the implement exhibited at

Aberdeen, which alone, of course, is entitled to be put in competition.

But, on being tried, this implement was withdrawn, as it was stated by the

exhibitors that it was not applicable to damp soil and luxuriant shaws.

The second implement had been made with an arrangement for a freer

separation of the potatoes from the earth and shaws; but this implement,

though exhibited, cannot compete, and the Committee have to report that

they do not. find Mr Aspinwall entitled to a premium.

The Committee take this

opportunity of reporting that the raising of potatoes and separating them

from the roots to which they are attached, and from the earth in which

they are embedded, without injuring their skin, is an operation not

without great difficulty, and it seems to them that in the implements

exhibited to-day, and in all others they have seen which profess to do the

work required, the speed of the revolving machinery employed in separating

the potatoes from the soil is far too rapid and violent to be consistent

with raising the potatoes in a state to be advantageously stored in pits.

The report was adopted.

VII.—Water-Testing

Apparatus.

This apparatus was

exhibited at the Aberdeen Show by Messrs Joseph Davis & Co., London, and

was tried by the Committee on the 28th of November. The Committee, after

experimenting with several of the tests, consider that they are well

known, but that they would be of comparatively little use in the hands of

a person not educated in chemistry. They are of opinion that no prize

should be awarded.

The Board approved of the

report.

VIII.—Murray's Thrashing

Machine.

This Machine was exhibited

by Messrs George W. Murray & Co., Banff, and was tried in the show-yard on

the 28th of July. It was seen at work with barley and oats, and did its

work in a very satisfactory manner. The Committee added that they found

that the price was moderate, and recommended that it be awarded the gold

medal. The board approved of the report.

IX.—Turnip Raisers. (By

Local Committee at Aberdeen.)

The local committee

appointed previous to the Aberdeen Show, 1876, met at Balhaggardy,

Inverurie, on Thursday the 30th of November. Present—Messrs Alex. Auld,

Newton of Rothmaise, Insch; James Reith, South Auchinleck, Skene; and

George Wilken, Waterside of Forbes, Alford. Messrs Robert Salmond, Nether

Balfour, Durris, and Alexander Yeats, Aberdeen, were unable to be present

in consequence of indisposition. The members present appointed Mr Wilken

to act in Mr Salmond's absence as convener, and also, in consequence of so

few of the local committee being able to be present, agreed to ask Messrs

Campbell, Kinellar, and Stephen, Conglass, two of the local committee, to

act as judges of the turnip-raisers along with those present. After

inspecting the four machines set aside for trial, all were considered

nearly the same as those exhibited at Aberdeen, and all were allowed to

compete. The field was admirably adapted for the purpose, being quite free

from stones, and the whole of the machines were very efficiently horsed by

Mr Maitland, Balhaggardy. The turnips were a superior crop, and at least a

fourth of an acre was allowed for each machine, both of Swedish and

yellows. There was little difference in the speed of either machine, all

performing at the rate of three-fourths of an acre per hour. The work

done, taken all over, was fair. The judges separated the machines into two

classes.

First-class machines that

topped and tailed, of which there were three entries:—

1st. James Thorn, Leden

Urquhart, Strathmiglo, No. 1694. This machine requires two horses, takes

one drill only, throws the turnips to one side, the same as a

potato-digger, and performs the work far superior to any of the others.

Recommend it be awarded a silver medal.

2d. Adam T. Pringle,

Edinburgh and Kelso, No. 652. This machine also requires two horses, takes

two drills, lifts the turnips and leaves them on the surface, and performs

the work fairly. Recommend it be awarded a medium silver medal.

3d. Duncan Boss,

agricultural factor, Inverness, No. 1617. This machine also requires two

horses, takes two drills, and simply tops and tails without removing them

from their original position. Recommend it be awarded a minor silver

medal.

Second-class machines that

tailed only, of which there was only one entry:—

John Gregory, Westoe, South

Shields, No. 1195. This machine requires only one horse, takes two drills,

tails only, and leaves the turnips in their original position. Recommend

it be awarded a medium silver medal.

The Board approved of the

report, and confirmed the awards as suggested. |