|

ON THE TREE MALLOW (LAVATERA

ABBOREA) AS AN AGRICULTURAL PLANT FOR CATTLE-FEEDING, PAPER-MAKING, AND

OTHER PURPOSES.

By William Gorrie, Rait

Lodge, Trinity, Edinburgh.

[Premium—Ten Sovereigns.]

Having, on the 4th May

1870, exhibited a specimen of the highly promising, but hitherto

neglected, bunch grass of British Columbia in the Edinburgh Corn Exchange,

the young spring growths of which measured at that early period from 3 to

3˝ feet in height, I was invited to show it the same day at a conference—

between the Directors of the Scottish Chamber of Agriculture and a number

of paper-makers from the surrounding districts— "on the practicability of

growing a useful material at home for the supply of the paper

manufacturers, as a substitute for esparto grass." In reply to inquiries

that were there made, I stated that if the straw of ordinary corn crops,

and that of our stronger growing native grasses, such as the common reed {Phragmites

communis), the reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and others,

possessed sufficient tenacity for paper-making, I believed that the bunch

grass (Elymus condensatus) would prove equally suitable; and that a

greater weight per acre of material could be got from it than from any of

the forementioned. In this opinion I am now more fully confirmed, from my

original plant, which was reared from seed in 1866, having since annually

yielded very dense close crops of both barren or leafy, and fertile or

seed-bearing stalks, which in each of the past six years measured from 9

to 9| feet in height. Having thus been led to look out for "paper-fibre

plants," I have now several highly promising exotic kinds under trial,

besides that indigenous one which forms the subject of the following

communication.

In July 1870 I spent some

days near Kildonan, in the south of Arran, when I was much struck with the

gigantic size and showy appearance of the many fine tree mallows which

were there grown for cottage-garden ornamentation, and had become

naturalized in some waste places. Two of the former were found to measure

fully 12 feet in height, while few were under 9 feet. In a long,

hedge-like belt of the latter I came upon a continuous mass of fibre,

stretched among a thick growth of grassy herbage, which turned out to be

the only remains of a large mallow plant that had fallen or been broken

down the previous season, and all else of which had rotted away. This

fibre I took with me, along with a sample of fresh bark; and having

subsequently secured specimens of the matured plants, as well as a supply

of the ripe seeds, I handed a portion of each to David Curror, Esquire,

secretary to the Chamber of Agriculture, who had the bark tested for its

fibre properties by Messrs A. Cowan & Sons, of the Valleyfield Paper

Mills, Penicuik; and the seeds analysed by Dr Stevenson Macadam. In a note

which Mr Curror sent me, dated 21st November 1871, he stated, "the results

are. that the stalks are worth L.5 per ton for paper-making; and the seeds

as valuable for feeding as linseed cakes."

Messrs William Blackwood &

Sons, of Edinburgh and London, having kindly transmitted a plant, and

sample of the green tree mallow bark to Messrs J. Dickinson & Co., of the

Nash Paper Mills, Hemel-Hempstead, for their opinion as to its properties,

they stated, in a letter, dated January 1873, "that the bark of the plant

contains a large proportion of fibre well adapted for paper-making

purposes, and possibly also for the manufacture of common cordage." They

estimated the market value of the bark at about L.8 per ton, and, by way

of encouraging an experiment, offered to take two or more tons at that

price. They also kindly inclosed a specimen of "half stuff " prepared from

the bark, and " showing the fibre to be of fair strength even when highly

bleached." Messrs William Tod & Sons, of the St Leonard's Paper Mills,

Lasswade, having made some experiments on a limited scale with the dried

bark, were so well pleased with the results that they offered, "at least,

L.10 per ton for it," that being the price they were then paying for

esparto grass, or about the same as the forementioned, L.5 per ton offered

by Messrs Cowan for the stalks, the bark and woody matter in these being

each nearly equal in weight. Mr Henry Bruce, of Kinleith Paper Mills,

Currie, having expressed a desire to experiment on a largish scale with

the mallow bark, his manager applied for from 1 to 5 cwts. of it—which

quantity I was unable to supply. This application, and the preceding

offers, induced me to undertake the aftermentioned culture of the tree

mallow in the Island of Bute, in which I was obligingly assisted by

Charles Duncan, Esquire of Woodend, Rothesay.

On the 7th of last August I

addressed a letter to Fletcher Norton Menzies, Esquire, secretary to the

Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland, of which the following is

an extract:—

"Agricultural Plant for

Cattle-Feeding and Paper-Making.—

A selected variety of the

tree mallow (Lavatera arborea), the natural habitats for the normal form

of which in Scotland are the Bass Rock, with other islets in the Firth of

Forth, and Ailsa Craig. Its ordinary heights vary from 6 to 10 feet, but

it can be grown to more than 12 feet. It is a biennial, but the first year

it may be planted, after the removal of any early crops, and matured in

that following. From the limited experiments which I have been enabled to

make, its products in seed, bark, and heart-wood are estimated at about 4

tons of each per acre. Chemical analysis by Dr Stevenson Macadam, and by

Mr Falconer King of its seeds, show these to be about equal in feeding

properties to oil-cake, the present value of which is about L.10 per ton,

and paper-makers offer the same price, at least, for the bark that they

now pay for esparto grass, which is also about L.10 per ton, thus showing

a return of about L.80 per acre for the seed and bark; and it is expected

that the excess of fibre in the latter will allow of the heart-wood being

mixed up with it, which will add very considerably to the above-stated

value of crop. The paper-makers who have had the tree mallow bark under

limited trial for me are Messrs Dickinson, Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead; Mr

Henry Bruce, Kinleith Mills, Currie; Messrs A. Cowan & Sons, Valleyfield

Mills, Penicuik; Messrs William Tod & Sons, St Leonard's Mills, Lasswade;

and Messrs William Tod, jun., & Co., Springfield Mills, Lasswade— all of

whom think very highly of it, and are most anxious to try it on a large

scale. With the view of having this done, I had plants reared in the

Island of Bute in 1875, and about two acres planted with them after the

removal of a crop of early potatoes. These plants throve well till a fall

of snow took place early in the winter, when the whole were destroyed by

rabbits. Bute was chosen for this trial in consequence of the winters on

the east coast being sometimes too cold for the mallow plants, many of

which suffer when the thermometer falls to about 15° Fahr., and most of

them are entirely killed when it falls much below 10°; which excesses of

cold, although occasional on the east coast, are never experienced on the

western coasts nor in the Orkney Islands, in various parts throughout

which, where the mallow has been tried, it has invariably been found to

thrive well; and I feel confident that it might there be made to yield

higher pecuniary returns, from hitherto comparatively worthless ground,

than ordinary agricultural crops do in the best cultivated districts of

Britain. Having already been at considerable trouble and expense in thus

experimenting with the tree mallow, and not caring to incur further

outlay, I have handed over my stock of seeds to Messrs P. S. Robertson &

Co., of the Trinity Nurseries here, who have now plants ready for

supplying any who may be desirous of carrying out its cultivation,

charging only 2s. 6d. per 100 to cover expenses."

The preceding communication

was read at the first meeting for the season of the Directors of the

Highland and Agricultural Society, and on the 2d November I was favoured

with the following:—

"Dear Sir,—At the

Directors' meeting held yesterday I was instructed to thank you for your

communication on the tree mallow. I sent your letter to the newspapers to

give the matter all the publicity we could.—Yours faithfully, F. N.

Menzies."

In course of the past

autumn I sent circulars of like import with the preceding to a

considerable number of landed proprietors and others, chiefly connected

with the western and northern coasts of Scotland, many of whom have now

fairly embarked in the experimental culture of the tree mallow.—See list

appended. The following are the analytical results above referred to:—

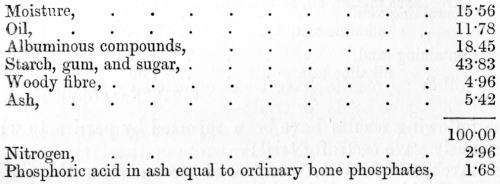

"Analysis of sample of

'Tree Mallow Seed,' received from D. Curror, Esquire, secretary of the

Chamber of Agriculture, Edinburgh. Grown at Kildonan, Island of Arran.

"The tree mallow seeds

possess the nutritive constituents of a good feeding stuff, and well

deserve a trial by the feeders of stock. It is not so rich in albuminous

or flesh-producing ingredients as linseed, or other well-known cakes, but

considering the loss of nutrient value in the manure when the richer cakes

are given to cattle, it is possible that the tree mallow seed would not be

much behind ordinary cake in feeding qualities.

"Stevenson Macadam, PhD.,

F.R.S.E.,

"Lecturer on Chemistry. "Analytical Laboratory, "Surgeons' Hall,

Edinburgh, 8th November 1871."

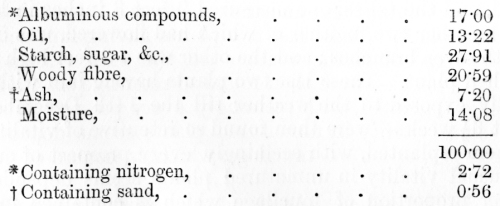

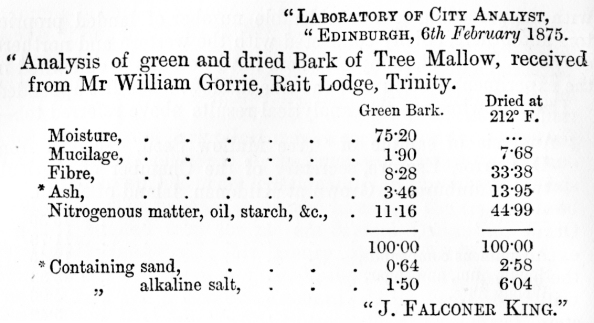

"Laboratory of City Analyist, "Edinburgh, 19ft December 1874.

"Analysis of Tree Mallow Seed, received from, and grown by, Mr W. Gorrie,

at Rait Lodge, Trinity.

"From the foregoing results

it is evident that this seed will form a valuable feeding stuff. It

contains quite as much oil as the generality of linseed cakes; and

although the amount of albuminous substance is lower than in ordinary good

linseed cake, it is not far out of proportion to the heat-giving

ingredients.

"J. Falconer King.

The following results have

been reported by parties to whom I previously gave seeds for trial:—

Mr Archibald Gorrie, then

wood manager for the Earl of Leicester, Holkham Hall, Norfolk, wrote on

the 17th August and 3d September 1874:—"A plant of the tree mallow No. 1,

grown by itself, yielded 10 lbs. of green bark, which was reduced to 4

lbs. by drying, and its dried seeds weighed 2 lbs. 13 oz. Plants 2, 3, and

4, grown in a row about 2 feet apart, yielded 16 lbs. of green bark, which

when dried was reduced to 8 lbs., and their dried seeds weighed 7 lbs."

Mr Robert Henderson,

manager for Colonel F. Burroughs, Island of Rousay, Orkney, writing on the

30th of October last, stated that—"The plants reared from your tree mallow

seeds, which were sown here in May 1875, have all flowered except three,

and we only want a little dry weather to ripen and secure the seeds well.

The average height of the plants is from 6 to 7 feet, and I send you by

steamer a sample." These plants came safe to hand, two of them were well

furnished with good ripe seed, and the tallest one measured 9 feet 3

inches in height. One of the other two, neither of which had flowered, was

5˝ feet high, with seven branches; and the other was a 2 feet high young unbranched plant. These last two plants having lain with their coots fully

exposed to the weather till the 14th December—in all about 6˝ weeks—were

then found so retentive of vitality that I had them replanted, with

seemingly every prospect of success. This unusual vitality in unmatured

plants seems dependent on the larger proportion of mucilage which is

contained in their bark.

Mr J. Smith, gardener,

Lewis Castle, Stornoway, writing on the 6th of last November, states:—"The

tree mallows raised from the seeds you gave me in June 1875 were much cut

up by hares, which appear to be very fond of them. Of those left the

tallest one is now about 7 feet in height, although it has not flowered. I

may state that last winter, or rather spring, was one of the severest on

record about Stornoway, and more than the usual amount of snow fell, with

which the ground was covered for nearly six weeks. The 2000 plants

received this autumn from Messrs P. S. Roberston & Co. have been

temporarily planted in the kitchen garden, where they will be safe

throughout the winter from the hares, and will be retransplanted in

spring. They are now growing nicely, not one of them having been lost."

The Rev. James Ingram, U.P. Manse, Island of Eday, Orkney, in a letter

dated the 4th December 1876, reports:—"My experience of the tree mallow

cultivation has been confined to the garden here, where, with a south

exposure and near a 7 feet wall, it attained a height of 9˝ feet, with 2

inches in diameter of stem, and there were numerous branches on all sides

wonderfully prolific in beautiful red blossoms. It continued flowering

three months, and almost the latest flowers produced ripe seed. The plants

in the east and west borders were not so large, being only 6 feet high and

proportionately small in other respects, but they produced a large

quantity of ripe seeds. I have not had a single plant uprooted by the

storms, though cabbages frequently suffer in that way." David Curror,

Esquire of Craigduckie, writes from Rosythe Cottage on the 26th

December:—"In 1875 about a dozen of the mallow plants, reared from the

seeds you gave me, had attained in their second year to a height of 14

feet, with 9 to 10 inches in girth of stem above the ground. These plants

blossomed freely, and a large quantity of seeds matured on each. An

unflowered plant, raised from seed last spring, which I measured

yesterday, was 83 inches in height by 8 inches in greatest girth of stem,

so that the growth of the tree mallow has been a perfect success here,

close to Rosythe Old Castle, on the north side of the Firth of Forth."

William Hay, Esquire,

Rabbit Hall, Portobello, planted a number of tree mallows in 1871, where

they were fully exposed to the north-east sea blasts, and where the

hardiest of sea-side trees and shrubs did little more than merely retain a

stunted existence. Here some of the mallows grew to fully 10 feet in

height; and one, bearing a full crop of seeds, having been broken down in

autumn 1872, these were greedily devoured by turkeys, and other domestic

fowls that, having thus acquired a taste for them, proceeded to attack

those on the standing plants, where it was amusing to see them flying up

and holding on by the slender top branches, devouring every seed they

could possibly get at. Writing subsequently to Mr John M'Kelvie,

schoolmaster, Kildonan, and Mr Robert M'Niell, Breadalbane Cottage in that

vicinity,—to both of whom I am indebted for specimens and

information,—they replied confirmatory of the liking for the mallow seeds

displayed by domestic poultry. And this farther points to their

applicability for feeding winged game and many other kinds of wild birds.

In addition to the cattle-feeding and paper-making properties of the tree

mallow, it may be beneficially and economically employed for other

purposes; such as—

Sheltering sea-exposed

gardens, and other grounds. At a meeting with the Largo Naturalists' Field

Club, some years since, the late Mr Dickson, one of the original

proprietors and editors of the "China Mail," who then resided at Elie, in

Fife, told me that his garden was so directly exposed to the sea winds and

spray that he had to grow a hedge-like belt of the tree, or, as it is

there called, the Bass Rock mallow, on the sea-ward side of his crops, for

their protection, and that it answered that purpose admirably. At a

meeting of the Scottish Arboricultural Society, held on the 1st of

November last, I recommended the tree, or as it is sometimes called the

sea mallow, as a nurse for sea-exposed young plantations, it being

peculiarly adapted for affording protection to the young trees before

these attain sufficient sizes to shelter one another. When thus employed

it is advisable to sow the mallow seeds in nursery drills or beds towards

the end of June, so that they may not flower next year, and transplant

them as soon as they are 4 to 6 inches high, where the forest trees are to

be planted next spring. For succession, another planting of like sized

mallows should be made in July or August following, to remain green and so

maintain the shelter after those first planted have seeded and been

harvested. Afterwards the seeds that will get scattered annually, even

with careful harvesting, will suffice to keep up a sufficient succession

as long as the sheltering aid of the mallows may be needed.

That "nutritive mucilage"

which is peculiar to the Malvaceae, or mallow family, and for the

esculent, emollient, and other properties of which the okra (Hibiscus

esculentus), the marsh mallow (Althea officinalis), and others are much

reputed, is also abundantly present in the tree mallow, from which it may

be obtained in sufficient quantities to allow of its being used as a

condiment in the less nutritious animal foods, such as cut straw, chaff,

&c, in addition to its more extended employment in culinary dishes,

comfits, and the manufacture of toilet soaps. The okra above mentioned is

extensively cultivated in tropical and subtropical countries for its pods

and seeds, the former in their young state being pickled like those of

kidney beans; the latter impart a mucilaginous thickening to soups, and

are used in the manner of green peas; when ripe they are boiled like

barley, and roasted as a substitute for coffee. The okra has also been

long recognized as a textile plant, and a patent has recently been taken

out in France for making paper from its fibre, for which it is being

extensively cultivated in Algeria. Its fibre is prepared solely by

mechanical means, in a current of water, without any bleaching agent, [See

"British and Foreign Paper-Makers' Review" for August 1876, p: 19.] a mode

that is also likely to be applicable to that of the tree mallow.

For green manure, to be dug

or ploughed into the ground, the rapid and luxuriant growth of the tree

mallow renders it particularly suitable. Some have assumed that, in

consequence of its immense growth, it must be a very scourging or

soil-exhausting crop. In reality, however, this does not appear to be the

case, for the plants have comparatively few, and by no means far-spreading

roots, and throughout the whole period of their growth, but more

especially in that of the first year, they shed an abundant, continuous

succession of their large succulent leaves, which overspread the ground

surface with a thick leaf-manure covering. Thus the plants are not only

large producers of their own nutriment, but seemingly derive much of their

sustenance from the atmosphere, as is evinced by the forementioned

tenacity of life in the unmatured plants.

For distillation, the seeds

of the tree mallow are likely to be useful. A friend to whom I showed

them, and who in America had much experience in distilling from buckwheat,

as well as from Indian corn, and the ordinary cereals, stated he had no

doubt but they would yield over a gallon of proof spirit per 50 lbs.

For the textile and cordage uses of the tree mallow, see after remarks,

page 295.

Cultivation.—The tree

mallow accommodates itself to a wide range of soils and situations, not

excluding from the former bog-peat, if sufficiently drained to free it

from stagnant moisture; and although it thrives inland provided the

temperature does not fall too low, it is most at home on the cliffs, and

among the earth-mixed debris of sea-side rocks, or among sea sand-hills on

their partly consolidated slopes and hollows. Under cultivation it will

grow on most soils that are suitable for ordinary farm crops, and in many

places where the exposure is too much for these. Ordinary farm-yard manure

may seldom be available for tree mallow culture, but a convenient

substitute will often be found in those immense quantities of sea-weed or

wrack that are often thrown ashore near places that are highly suitable

for its growth. The droppings of sea birds on its native cliffs suggests

the application of guano; and in inland localities common salt could not

fail in being highly efficacious. The period at which plants naturally sow

or disperse their seeds is generally deemed the best, or at least a good

time for sowing them in their native countries. To this rule, however, the

tree mallow may be deemed an exception; as a good many of its earliest

fallen seeds vegetate in mild periods of the succeeding autumn and winter

months; and although in very sheltered places these may escape yet in

many cases most of them will succumb to the succeeding winter and

spring frosts. Hence it will generally be found preferable to sow the

seeds between the middle of March and the end of April, as if much longer

delayed many of the plants will not flower the next year, but assume a

triennial in place of a biennial duration. The seeds being sown either in

drills or broad-cast, the young plants, when about 6 to 10 inches high,

should be transplanted to where they are to remain, or in case of the

ground being then filled with an early crop, such as early potatoes or

pease, they may be temporarily transplanted at 4 to 6 inches apart till

such crop is removed and the ground prepared for them; when they should be

planted out either by the dibber or plough at from 18 inches to 4 feet

apart; till more experience shows the distances that are most suitable for

them in different soils and situations. When to be grown on the most

exposed sea-coasts, either as an exclusive crop or for sheltering young

plantations, they should be planted out when about 4 inches high, or the

seeds sown in the places where they are to grow. No plants—those of kale

and cabbage not even excepted—stand transplanting better than those of the

tree mallow; but when its seeds become sufficiently abundant, it may in

some cases be found best to sow them by machines, and afterwards thin out

the young plants as is done with turnips. Intending cultivators should

guard against getting their seeds off inferior varieties, such as that of

the Bass Rock, which is dwarfer, as well as more horizontally spreading

and more branching than the one here recommended. They should also avoid

getting seeds from Southern Europe or other warmer climates than those of

its British habitats. This last precaution may be deemed as of only

temporary application, seeing that from the number of experimental

growers, and the quantity of plants they have already planted out, or that

will be so sufficiently early next summer, an abundance of home seed for

sowing, as well as for practically testing its cattle-feeding qualities,

will be produced in the autumn of 1878. And as with other cultivated

plants the tree mallow can doubtlessly be improved by selection, careful

cultivators will do well to select their " stock seeds " always from the

best plants.

The thrashing or separating

of the seeds front the stalks or haum, may either be done by rippling

combs, as with the flax; by flails, or by machinery. It is probable that

it may be found advisable to cut off or separate the seed-bearing twigs

from the thicker branches and stems, as doing so would likely facilitate

the after operations of stacking or storing, thrashing, and peeling.

Peeling or stripping off the bark is easily done at all times during the

growth of the plants, and only a little less so when the seeds are

sufficiently matured for pulling or cutting the crop: while even after the

stalks are dried by stacking, or standing them out on end through the

winter, the bark comes off quite freely if they are saturated for a short

time in water, or even thoroughly wetted by rain.

The principal advantages to

be derived from the cultivation of the tree mallow are its production of

two crops or returns—seeds and fibre—either of which would alone

remunerate its growers; its suitability for extensive districts which are

now almost worthless, or only capable of bringing low pasture rents; the

prevention or abatement of river pollutions, as little if any caustic soda

or other deleterious chemicals will be required in the preparation of its

fibre; its resistance of injury from wet weather at, and after harvesting.

And for the encouragement of such as wish to try it where the winters are

occasionally too cold, it may be stated that plants of only one season's

growth will yield a profitable return of good fibre, should they happen to

be killed by frost. In addition to the forenamed Scottish habitats of the

tree mallow, it is also indigenous on some parts of the south-west of

England and Welsh coasts; while in the "Cyble Hibernica," by Dr David

Moore and Alexander G. More of the Glasniven Botanic Gardens, it is stated

to be found wild in five of the twelve divisions that therein comprise the

map of Ireland, only one of which is on its eastern, and the other four on

its southern and western coasts. So that in the western and northern

coasta of Scotland, its Western Isles, the Orkneys, and probably the

Shetland Isles, added to the other sufficiently mild tempera-tured

districts of Great Britain and Ireland, it may be safely inferred that a

much greater extent is available for tree-mallow culture than would

suffice for all the wants of our home paper manufacturers,—and that

without lessening materially the land surface presently devoted to

ordinary agricultural crops. Continental Europe, it may be remarked, is

too cold in winter for the Lavatera arborea, except those districts which

border on the Atlantic and Mediterranean; and the same may be said of the

Northern United States. In short, as beforementioned, no place' is

suitable for its regular cultivation where the temperatu frequently falls

below 15° Fahr. in winter.

In Lawsons'

"Agriculturists' Manual," published in 1836, the Lavatera arborea is

included in the section "Plants Yielding Fibre," from its having been

shortly before recommended by M. Cavanilles for "producing a very strong

fibre which may be employed for making ropes," &c. In August 1876 Lady

Orde kindly favoured me with the perusal of a letter from Mr Freer of

Rayden, Norfolk, in which he stated that Mr William Billington, who was

deputy-surveyor for the woods and forests at Chopwell, Durham, and

afterwards resided at Bay Towers-on the west coast of county Mayo, where,

exposed to all the storms of the Atlantic, Lavatera arborea flourished in

native wildness, recommended its fibre for paper making. He also used it

in his garden for tying instead of bast; but the use of its seeds as

cattle food does not seem to have occurred to him." In a syllabus of

lectures on substitutes for paper material, delivered by Dr W. Lauder

Lindsay at Perth in 1858, the "tree mallow" is named in conjunction with

the common mallow, in a list of 75 paper-yielding plants. In September

1875 Dr W. L. Lindsay directed my attention to an article "On the

Manufacture of Hemp and Paper from the Lavatera arborea," which was read

before the Royal Dublin Society on the 25th of March 1859 by Mr Robert

Plunkett, and published in the "Natural History Review " for that year.

Having failed to obtain a copy of that publication in Edinburgh, I applied

to Dr D. Moore of the Glasniven Botanic Gardens, who being equally

unsuccessful in Dublin, kindly had the article copied verbatim, and sent

to me on the 16th of December last,—from which it appears that at the said

meeting were exhibited "products of the sea tree mallow, patented by

William George Plunkett, July 29, 1857. No. 2069." These products were

taken from plants over 6 feet in height, that were sown in spring and cut

in October; as well as from a year and half old plants of 10 feet in

height. They consisted of three specimens of hemp, made from the bark of

the stems and branches; card boards made from the fibre and wood of the

plant, of which those from the wood were lightest in colour; together with

five kinds of rope and cordage; but no paper seems to have been shown. Mr

Plunkett having, however, sent a series of specimens to Mr Cooke of the

Trinity House Museum, Lambeth, that gentleman, in a contribution to "The

Art Journal " for the 14th of January 1859, stated that "another patent,

or rather series of patented paper pulps, are those of Mr Plunkett of

Dublin, whose papers are made from four different kinds of plants. These

are the tree mallow, red clover, hop bine or straw, and the yellow water

iris; to the first of these we may look perhaps for the most satisfactory

result." Mr Cooke farther added, that "specimens of the plant, wood, hemp,

cordage, fine thread, and lace made from the bark, together with paper

made from the wood, I shall be happy to show any one interested in the

experiment." This employment of the heart-wood for paper-making is

confirmatory of the anticipated use of it as stated in my previously

recorded letter to the Highland and Agricultural Society, page 287. In a

recent conversation with Dr D. More, he told me that, when at the Brussels

Great Centennial Horticultural Exhibition last spring, the cultivation of

the Lavatera arborea for papermaking in Belgium was then talked of by

several gentlemen he met. But it is feared that Belgian winters are

generally too severe to admit of this being done successfully. The

"Gardeners' Chronicle " of 11th November last contained an abridged copy

of my letter, quoted at page 287, which was concluded by the editorial

remark, that "years ago the utilization of this plant was suggested by the

late Mr Hogg and by the editors of this journal."

The above series of

quotations show that I have no claim to the original discovery of the tree

mallow being a fibre-producing plant, although my attention was drawn to

it in entire ignorance of these prior claims. Hence my investigations and

experiments with it are likely to be the more useful, from having been

conducted independently of previously ascertained facts and failures

regarding it. The use of the seeds for feeding, and some of the other

purposes for which I have recommended the plants and their products, have,

however, claims to novelty; and I trust that the means I have taken to

bring its merits fully before both cultivators and manufacturers may

result in the complete realization of the advantages herein held out to

both. A usual question that has been put to me is: If the tree mallow is

really so useful as you represent it, how does it happen that its

usefulness has not been previously known? The preceding paragraph shows

that its properties have not been altogether, although partially,

overlooked; but even such as were ascertained do not seem to have been

brought under the notice of those most deeply interested in any practical

form. A patent taken out for the manufacturing of mallow fibre is just one

of that class most likely to be shelved or laid aside and no more thought

of. For in the first place a manufacturer requires a large and constant

supply to justify him in making the requisite machinery alterations to

allow of the new material being successfully wrought out; and he would

have to set about providing for his new supplies of material about two

years prior to the first crop being produced. And in the second, place few

tenant farmers, even if permitted by their leases, would care to embark in

experimental cultivation of any kind that would take about two years

before pecuniary returns could be realized, and that more especially in

the face of patent restrictions. Hence it is only by the combined efforts

of landlords and manufacturers that tree mallow cultivation and its

products can be fairly introduced. But when this is once successfully done

tenant farmers, if allowed, will soon take to this new branch of

agriculture.

In order to facilitate the

exchange of opinions regarding results among the growers; and that other

interested parties may know where to see, and judge for themselves, the

following list is given of the names of those who up to the date of

publication have embarked in the cultivation of Tree Mallow:—

His Grace the Duke of

Argyle, Inveraray Castle.

His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch, Dalkeith Park, &c.

His Grace the Duke of Richmond and Gordon, Gordon Castle.

His Grace the Duke of Sutherland, Dunrobin Castle.

The Most Noble Marquis of Ailsa, Culzean Castle.

The Eight Hon. the Earl of Derby, Knowsley.

The Eight Hon. the Earl of Stair, Lochinch House.

The Eight Hon. Lord Kinnaird, Rossie Priory.

The Eight Hon. Lord Henry Scott, Beaulieu, Southampton.

Sir E. C. Dering, Bart., Surrendew-Dering, Kent.

Sir J. D. H. Elphinstone, Bart., M.P., Logie Elphinstone.

Sir James Matheson, Bart., Lewis Castle, Stornoway.

Sir J. P. Orde, Bart., Kilmory, Lochgilphead.

James Alexander, Esquire of Red Braes, Bonnington.

John Anderson, Esquire of Denham Green, Trinity.

Alexander Baird, Esquire of Urie, Stonehaven.

C. Bates, Esquire, America Farm, Doyenham.

John Binning, Esquire, Brae, Dingwall.

Colonel F. Borroughs, Island of Rousay, Orkney.

James Brown, Esquire, Goodrington House, Devon.

Henry Bruce, Esquire of Ederline, Ford, Ardrishaig.

John Bruce, Esquire of Sumburgh, Shetland, and Fair Isle.

Higford Burr, Esquire, Aldennaston, Reading.

------Callingford, Esquire, 7 Phillimore Gardens, Kensington.

J. J. Caiman, Esquire, Carrow House, Norwich.

Donald Cameron, Esquire of Lochiel, M.P., Auchnacarry.

Blanchard Clapham, Esquire, Algoa Bay, South Africa.

Charles Davidson, Esquire, Kirkwall, Orkney.

William Delf, Esquire, Great Bentley, Colchester.

Jerome Dennison, Buegar House, Evi, Orkney.

------Drattry, Esquire, Oakdale, Holmwood, Dorking.

Charles Duncan, Esquire, Woodend, Island of Bute.

James Duncan, Esquire of Benmore, Kilmun.

H. Newby Fraser, Esquire, Home Farm, Roseneath, Kilcreggan.

R. W. Ganssen, Esquire, of Brookman's Park, Hatfield, Herts.

A. Gibson, Esquire, Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand.

John Gordon, Esquire of Cluny.

A. M. Sutherland Graeme, Esquire, of Graemes' Hall, Orkney.

David Milne Home, Esquire, of Wedderburn, Paxton House,

Berwick. Edward Humphries, Esquire, Mount Pleasant Hall, Worcester.

James Hunter, Esquire, 1 Doune Terrace, for the Neilgherry Hills, East

India.

Rev. James Ingram, U.P. Manse, Island of Eday, Orkney.

Charles Jenner, Esquire, Easter Duddingstone, Portobello.

Professor G. Lawson, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Charles M. M'Donald, Esquire, Largie Castle, Island of Islay.

Kenneth Mackenzie, Esquire, Dundonnel House, Ullapool.

Angus Mackintosh, Esquire of Holme, Inverness.

George Marwick, Esquire, Bu Farm, Hoy, Stromness, Orkney.

H. K. Morran, Esquire, Inveryne, Tighnabruaich.

Walter Ovens, Esquire of Torr, Torr House, Castle Douglas.

H. 1ST. Palmer, Esquire, Down Place, Harting, Petersfield.

Dr Robert Paterson, St Catherine's, Inveraray.

Donald Robertson, Esquire of Pennyghael, Island of Mull.

J. M. Robertson, Esquire, Acuttipone Tea Co., Cachar, East India.

John Shaw, Esquire, Bowden, Manchester; and Southport Gardens, Liverpool.

William Sim, Esquire, Rosefield Nurseries, Forres.

John Tod, Esquire, St. Leonard's Paper Mills, Lasswade.

Colonel Tomlin, Orwell Park, Ipswich.

Charles Turner, Esquire, Royal Nurseries, Slough.

J. W. Webb, Esquire, Cradley, Malvern, Herefordshire.

A. P. Welch, Esquire, Hart Hill House, Luton, Bedfordshire.

Monsieur A. W. Welch, La Tour, Ajaccio, La Corse, France.

James Young, Esquire of Kelly and Durris.

Messrs J. Ballantyne & Son, Nurseries, Dalkeith.

Messrs A. Cowan & Sons, Valleyfield Mills, Penicuick.

Messrs Robert Craig & Sons, Newbattle Paper Mills.

Messrs Dickson & Co., nursery and seedsmen, Edinburgh.

Messrs Little & Ballantyne, nursery and seedsmen, Carlisle.

Messrs P. S. Robertson & Co., nursery and seedsmen, Edinburgh.

Messrs E. Sang and Sons, nursery and seedsmen, Kirkcaldy. |