|

By James Macdonald, Special

Reporter for the Scotsman, Aberdeen. [Premium—Thirty Sovereigns.]

General and Introductory.

The county of Fife has

pre-eminent claims to the dignified title of the "Kingdom," with which it

is frequently honoured. It is more largely surrounded by water than any

other county in the mainland of Scotland; and few counties in the United

Kingdom are more self-supporting—so extensive and so valuable are its

manufactures, so varied and so rich are the treasures of its rocks and the

production of its soil.

Fifeshire is attached to

the mainland of Scotland only by a narrow band on the western side, where

it joins the counties of Kinross, Clackmannan, and Perth. Its other three

sides are bathed in the waters of the ocean—the south by the Firth of

Forth, the north by the Firth of Tay, and the east by the German Ocean. It

lies between 56° and 56° 28' north latitude, the "East Neuk" being in 2°

35', and the most westerly point in 3° 43' west longitude. From east to

west it averages about 36 miles, and right down the centre from north to

south it measures about 14 miles. It has been ascertained by the Ordnance

Survey that the area of the county is 513 square miles, or 328,427 acres.

About four-fifths of the whole area is under regular cultivation, the

greater portion of the remainder being under wood. The county is divided

into 64 parishes, a number of which are by no means large. The population

in 1871 was 160,735, and the number of inhabited houses 27,056. There are

in all 10,410 owners of land in the county, 8638 having less than one

acre, or 1517 acres divided amongst them; while 1772 have possessions

exceeding one acre in extent, or in all 302,846 acres. In 1872-3, when the

return of owners of land in Scotland was taken up by the Government, the

gross annual value of the possessions of 1772 large landed proprietors was

L.741,379, 10s.; and those of the 8638 small land owners, L. 164,197, 17s.

The gross annual value of the whole county, exclusive of burghs and

railways, according to the Valuation Roll for 1874-5, is L.698,470, 13s.

l0d. The total valuation of burghs is L.208,002, 8s. 4d., and of railways,

L.49,957—grand total, L.956,430, 2s. 2d.

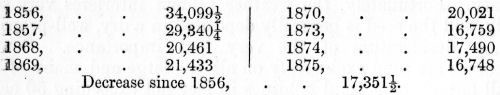

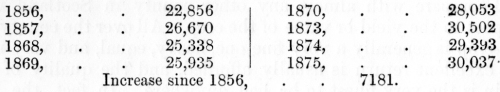

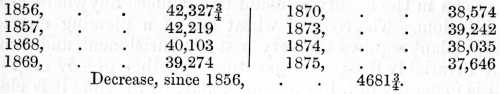

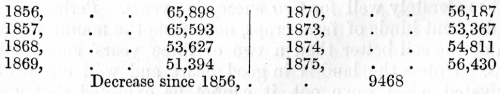

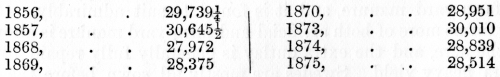

The Board of Trade returns

for the present year (1875) state the total number of acres under all

kinds of crops, bare fallow and grass, at 243,669 acres, of which 16,748

were under wheat, 30,037 barley or bere, 37,646 oats, 1304 rye, 2483

beans, and 109 peas, being a total under grain crops of 88,327 acres. The

average under green crop was 47,460 acres—28,514 under turnips, 17,746

potatoes, 34 mangold, 23 carrots, 88 cabbage, kohl rabbi, and rape, and

1055 vetches and other green crop. Of permanent pasture there is 50,261

acres, and of grasses under rotation, 56,430 acres, and of bare fallow, or

uncropped arable land there is 1189 acres.

Though almost every corner

of the county is the scene of great enterprise and no little activity, it

cannot be said that the general aspect of Fifeshire is strikingly

commercial. On the contrary, it has the appearance of being a quiet,

retired rural spot, where the aesthetic has never been wholly lost sight

of. Few counties in Scotland, if indeed any, can boast of a larger number

of baronial residences and gentlemen's seats than are to be found studding

and beautifying the undulating landscape of Fifeshire. The number of

landed proprietors is larger than in any other county of similar size in

Scotland, and the fact that these worthy gentlemen, with a few exceptions,

have all along been in the habit of residing on their desirable

possessions in Fife, explains the preservation of the county from the

modernising hand of trade and commerce. Not that they have hampered the

spread of industry and enterprise,—they have encouraged and aided the

development of every healthy industry in a manner that reflects upon them

unbounded credit,—but they have with equal care and rigour preserved the

amenities of their native county. Even in the greatest mining centres

where coal-pits are seen to the right and to the left, the scenery is very

fine, being beautified by numerous clumps of trees; while in the purely

agricultural districts, the carefully cultivated fields are tastefully

fringed by thriving belts of wood. The surface undulates considerably, yet

there are no high hills, the point of greatest eminence—West Lomond—being-only

1713 feet above the level of the sea. The Largo Law hill, situated in the

parish of Largo, on the south coast, rises to a height of 1020 feet, and

commands a magnificent view of the Firth of Forth and the city of

Edinburgh. The Lomonds lie at the north-west of the county, and impart to

the scenery around them an aspect which contrasts strikingly with the

landscape along the seaboard. Seated on the highest eminence of these

hills on a clear day, and provided with a powerful binocular field-glass,

one can command a most exquisite view. At our feet lies the historical

Kingdom of Fife spread out like a magnificent carpet, while away in the

distance the prospect is grand in the extreme. Southwards we see the low

winding ranges of the Pentlands and the Lammermuirs, and the richly

cultivated Lothians; to the west lies, dimly shrouded, the lofty Ben

Lomond; to the north, the rugged range of the Grampians; and, turning to

the east, the prospect softens down to the blue haze of the German Ocean.

The smaller objects of attraction in this wide range are far too many to

be enumerated, but, in a word, it may be said that the prospect is one of

the finest to be had anywhere in Scotland; and what country can boast of

grander prospect than the

"Land of brown heath and

shaggy wood"?

There are no very large

plantations, the wood being pleasantly strewed over the whole county in

thriving clumps, diversifying the scenery and lending a lustre to the

charm of the landscape. The county has no less than 85 miles of a coast

line, considerable portions of which are bold and rocky, and indented here

and there by miniature bays. Between Wemyss and the "East Neuk" a pretty

large stretch is low and sandy, and parts of it strewed with massive

pieces of rock; while on the east it is irregular and very rocky, and on

the north-east plain and sandy.

There are only two rivers

worthy the name—the Eden, which rises in the parish of Arngask, and after

a quiet winding course of about 24 miles, empties itself into St Andrew's

Bay; and the Leven, which has a course of only 12 miles, rising in Loch

Leven, in the parish of Portmoak, and falling into the Firth of Forth at

Leven. The next largest stream is the Orr—a slow muddy stream winding from

the Saline hills easterly to Dysart. There are several very small

streamlets throughout the county, the most of which are tributaries of the

Eden, the Leven, or the Orr. The Eden and the Leven at one time were

valuable salmon rivers, but now mill-dams and manufactories disturb the

fish and make the rivers almost worthless in this respect. The

trout-fishing, however, is excellent on nearly all the waters, as also in

several of the lochs. There is a number of lochs in the county, but the

majority of them are very small, the principal ones being Lindores —about

four miles in circumference; Lochgelly, about three miles in

circumference; and Kilconquhar, about two miles in circumference. Moors

are neither numerous nor large, and game very scarce, hares and partridges

being the predominating species. The majority of the landlords preserve

their shootings; but it is seldom that game grievances disturb the

political atmosphere of Fife. In the higher parts, adjoining Kinross,

there is a considerable quantity of peat-moss, and deposits of moss are

met with here and there throughout the county.

One important feature of

Fife is the very large number of towns and villages that are scattered

over the county. There are no fewer than fourteen royal burghs, and a

whole host of villages, chiefly along the coast. Cupar is the county town.

It is situated on the river Eden, has a population of 5105, and is a

cleanly kept busy little town of great antiquity. By far the largest town

is Dunfermline, situated at the south-west end of the county. During the

past two centuries it has risen from an unimportant rural village to one

of the principal manufacturing towns in Scotland. It has a population of

14,963, is yearly extending in magnitude, and may be called the commercial

capital of the county. St Andrews, once the ecclesiastical capital of

Scotland, is a city of very great interest to the antiquary, because of

the peculiarly eventful character of its ancient history. It was

constituted a royal burgh by David I. in 1140, and was once a most

populous town, but since the Reformation it has dwindled away

considerably, and now it can number only 6316 inhabitants. The University

of St Andrews was founded in 1411 by Bishop Wardlaw, and is thus the

oldest university in Scotland. The "Lang Toon" (Kirkcaldy), famous for its

manufactories and as the birthplace of Adam Smith, the talented author of

the "Wealth of Nations," has an industrious population of 12,422; while

Dysart, situated on the coast two miles northeast from Kirkcaldy, numbers

8919 persons. Burntisland, a rising-watering-place, stands on the coast

almost immediately opposite Edinburgh, and has a population of 3265. It is

surrounded by scenery of great grandeur, is held in high repute as a

watering-place, and during the summer months, when it is resorted to by

hundreds of the inhabitants of Edinburgh and other towns, is the scene of

no little life. The village of Lower Largo is famous as having been the

birthplace of Alexander Selkirk, the prototype of "Robinson Crusoe," while

Anstruther-Easter, a royal burgh with a population of 1,289, ranks amongst

its sons with pardonable pride the celebrated Dr Chalmers. The ancient

history of the county of Fife is of much more than ordinary interest on

account of its being so closely connected with the life and history of the

kings of Scotland. Anything merely historical is beyond the range of this

report, but a few sentences may be given. At one time the entire district,

comprising Fife, Clackmannan, Kinross, the eastern part of Strathearn, and

the country west of the Tay, as far as the river Braan, was inhabited by

the Horestii, a Celtic race, and was designated Ross, meaning a peninsula.

The peninsula was partly divided about 450 years ago, but it was not till

1685 that the county of Fife was reduced to its present size. At the time

of the Roman invasion the Celts were driven from their peninsular domain,

and after the Romans came the Picts, who united with the Scots about the

middle of the ninth century. In 881, and in several subsequent years, the

Danes invaded the county and troubled the inhabitants dreadfully. Down

till 1424 the Thanes of Macduff held sway over the greater portion of

ancient Fife, but on the execution of their last chief, Murdoc, their

estates were confiscated to the Crown, and Falkland Palace, the residence

of the Thanes, became the property and abode of the kings of Scotland.

Since then the social atmosphere of Fife has been comparatively clear and

tranquil, while enterprise and enlightenment have all along been the order

of the day. It is worthy of mention that Malcolm Can-more, David I.,

Malcolm the Maiden, Alexander III., Robert Bruce, his Queen Elizabeth and

nephew Randolph, Annabella, Queen of Robert III., and Robert Duke of

Albany were buried in the Abbey of Dunfermline, an antiquated ruin,

founded by Malcolm III. about 1070. In digging for the foundation of the

new parish church in 1818 the tomb of Robert Bruce was discovered, and his

skeleton found wrapt in lead.

The county sends one member

to Parliament, the present representative being Sir Robert Anstruther,

Bart. of Balcaskie; while Cupar, St Andrews, East and West Anstruther,

Pittenweem, Kilrenny, and Crail have one member—Mr Edward Ellice; and

Kirkcaldy, Dysart, Kinghorn, and Burntisland another—Sir George Campbell.

Dunfermline and Inverkeithing are conjoined with the Stirling District of

Burghs; and by the Reform Act of 1868 the Universities of St Andrews and

Edinburgh were combined into one constituency, their present

representative being Dr Lyon Playfair. The county is divided into two

districts, an eastern and western, for judicial purposes, and each

division is under the jurisdiction of a sheriff-substitute. For civil

purposes it is divided into four districts, viz., Cupar, St Andrews,

Kirkcaldy, and Dunfermline.

The railway system now

extends to nearly every district of the county, while the ferry-boats at

Burntisland and Tayport bring the county into close connection with the

principal centres of trade and commerce in Scotland. The expenditure on

railways within the county during the past ten or twelve years has been

very great, and if once the branch—now in process of construction—from

Dunfermline to Inverkeithing and Queensferry were opened, the system will

be almost complete. In the matter of roads also the county is well

accommodated.

A monthly cattle market is

held at Cupar, while similar fairs take place at stated times at other

parts of the county. During the winter and spring grain markets are held

weekly at all the principal agricultural centres. The proximity and easy

access, however, to the Edinburgh markets make farmers less dependent on

the local fairs for the sale of their stock and grain than they would

otherwise be.

Population.

The following table shows

the population of the county at various stages during the past

seventy-four years:—

1801, 93,743

1811, 101,272

1821, 114,556

1831, 128,839

1841, 140,140

1861, 154,770

1871, 160,735

The increase since 1801, it

will thus be seen, is 66,992; and it is worthy of notice that the increase

has been gradual and constant. The number of inhabited houses in 1851 was

24,610, now it is 27,056, and the number of separate families 38,038. The

present population is equal to about 313 to the square mile, or little

more than 2 to each acre; or to put it exactly, 53 to every 26 acres. The

average number of persons to each house is very close on 6, The

topographical nomenclature—the touchstone of the ethnographer—of the

county of Fife is sufficient to demonstrate the fact that the aboriginal

inhabitants were Celts. The number of farms and places designated by

Celtic names is very large, and it is peculiarly interesting to note the

striking similarity that exists between the local names of Fife and those

of several of the northern counties of Scotland, a fact that speaks of a

similarity or kinship between the original inhabitants of Fife and those

of the north. The Horestii—the name given to the tribe of Celts that

originally inhabited Fife, or rather the peninsula of Ross—were not

characterised by industry or enterprise, and like their kinsmen in the

north must have had often to be satisfied with a scanty meal; for in those

days Fife is described as having been nothing else than an immense forest

full of swamps and morasses and inhabited by wild beasts. They had no

towns in their possession, but occupied hill forts, the remains of many of

which are still to be seen at several spots throughout the county. The

Horestii were almost wholly annihilated by the Romans, who in turn were

succeeded by the Picts, that ancient Celtic race, regarding whose origin

and early history so much has been written and spoken. Fifeshire formed

part of the southern boundary line of the Pictish territory, the English

having then possessed the Lothians and the independent Britons the kingdom

of Cumbria, while the Scots, another Celtic race that inhabited

ancient Scotland, or in other words the "Emerald Isle," occupied the

western coast from the Firth of Clyde to Ross-shire. Towards the middle of

the ninth century the two Celtic races—the Picts and the Scots—united, and

lived peaceably until disturbed by the ambitious Danes, who invaded Fife

in 881. From that time down till 1424, when the extensive lands of the

Thanes of Macduff (who possessed the greater portion of Fife) were, on the

execution of Murdoc the last chief of the Thanes, confiscated to the

Crown, the county frequently sustained considerable damage at the hands of

invaders. In the days of James V., who resided at Falkland Palace, the

social condition of Fife, like the most of Scotland, was not of the

brightest or the happiest description. But the reign of that unfortunate

monarch may be noted as one of the turning points, a new point of

departure, in the social history of Fife, for ever after the county has

been found in the van of progress. The advance in the social and

intellectual scale during the present century has been most marvellous;

and Mr Westwood, in his "Parochial Directory for 1862," says that "perhaps

nothing gives that progress so much prominence as the magnitude attained

by the newspaper press connected with the county. Previous to 1822 there

was no newspaper published in Fife, and the practice was to advertise

county and other public meetings in an Edinburgh newspaper, and a few

hundreds would probably cover the sum total of every newspaper that found

an entrance into the county. At present (1862) Fife can boast of ten

weekly newspapers and advertising sheets, besides three with a fortnightly

issue, having a total circulation of 25,000; nor is this all, for the

circulation of Edinburgh and other newspapers not connected with the

county is at present ten times more than it was when no native broadsheet

existed. All this, without taking into account the immense circulation of

periodicals and books of every shape and size, which forty years ago had

no existence, exhibits an intellectual progress penetrating to all classes

of our society, and exerts an educational influence unequalled in any

country or in any age of the world." Even since 1862 there has been

considerable improvement in the social condition of the county. The

educational machinery, always abreast of the times, has been improved and

extended a good deal of late, and is now second to that in no other county

in Scotland; while the position and influence of the newspaper press has

been greatly strengthened. The mining and manufacturing interests being so

extensive, the number of commercial men in the county is necessarily

large, and these as a class are sharp, shrewd, intelligent, and well to

do; while the farmers, generally speaking, are independent, industrious,

enterprising, comfortably-conditioned men, several of them wealthy. The

working population have superior advantages in the way of house

accommodation, and are well-behaved, economical, industrious, and

trustworthy. Miners, an exclusive class of men, not always credited with

peaceful social habits, form an important class in the county. Barring a

little roaring now and again, however, about strikes and trades unions,

Fifeshire has little to complain of in this respect. There is less stir

and bustle now, however, in the mining centres than some two or three

years ago, when the revolutionary movements in the mining world were at

their height. On a summer's Saturday afternoon some two years ago it was

almost an absolute impossibility for ordinary persons to obtain a cab or a

carriage of any description in Dunfermline for an hour's drive, the

miners, rampant with their ten shillings a day, having them all engaged

for a drive "into the country."

The dialect of the county

is varied. The ordinary people speak mixed Scotch, while in the higher

circles English only is heard. Throughout the county generally several

antiquated social habits still obtain. The farmers, for instance, in

speaking of the produce of their farms, calculate by the Scotch acre

instead of by the imperial acre as in most other counties, while the

ancient system of regulating rent by the fiars is still adhered to in many

cases. Sporting is indulged in only to a limited extent. There is one pack

of foxhounds and one pack of harriers, and no fewer than forty-one curling

clubs in the county; but the favourite outdoor sport seems to be the

"royal game of golf." The links at several of the towns and villages along

the coast are specially adapted for golf, and during the summer they are

all taken full advantage of. The county can also boast of a very

creditable body of mounted volunteers, as well as a strong regiment of

rifle volunteers.

Climate.

The climate of the county

is modified by proximity to the sea. It is not so variable, not so cold in

winter nor so hot in summer as in larger continental areas of country. The

climate is mild, and the air humid and healthy, while the rainfall is not

by any means heavy. In the darker ages, when the extensive valleys lay in

spongy swamps, foul mists continually shrouded the county, keeping it

constantly in a damp, disagreeable, unhealthy state. These mists are

peculiarly trying to delicate constitutions, while they foster and

encourage disease of various kinds, and man and beast often suffered very

considerably from their prevalence. As the ignorant feudalisms and rude

barbarities of ancient Fife have been swept away by the current of modern

culture and the spread of civilisation, these dingy mists have disappeared

before the enterprising agriculturist. Thorough drainage and improved

cultivation have completely revolutionised the county of Fife—have changed

it from an unhealthy swampy waste, a nursery for wild beasts, into a rich

agricultural county. Occasionally several of the valleys are still visited

by floating mists and "hoar" frosts, and in the month of July grain and

potatoes are heavily damaged thereby, while in winter turnips in low

ground often fall victims to these hoar frosts. But the loss sustained in

this way is trifling compared with what was experienced some fifty or

sixty years ago. Westerly winds prevail, but sometimes in spring and

autumn biting east winds sweep along the east coast, especially in spring,

doing slight damage to the young crops. The numerous belts and clumps of

wood, however, that stud the fields break and soften the current of the

wind, and lessen immensely the damaging effect on the crops. The climate

varies a little in some parts of the county, being a little more rigorous

in the higher lying parts than in the valleys and on the coast. Severe

passing storms of wind and rain sometimes sweep along the coast from the

German Ocean, but it is seldom that snow lies to any great depth or for

any length of time on the lands near the sea. The higher lands and hills

in the interior are often clothed in a snowy mantle in November, and

coated to the depth of several inches now and again during the winter. On

the whole, the winters are comparatively open, and agricultural operations

are rarely suspended in consequence of the weather. Rough weather seldom

prevails in spring, while the harvests, or rather autumns, are invariably

favourable. Vegetation commences early and continues far through the

season, The flora of the county is peculiarly rich, and interesting to the

botanist. The Thalami-floral orders, the Crowfoot (Ranunculaceœ) family

especially, are extremely well represented, at least one species of the

genus Tha-lictrum being found in Fife and in no other county in Scotland.

The rainfall during the year generally averages about 21½ inches, or

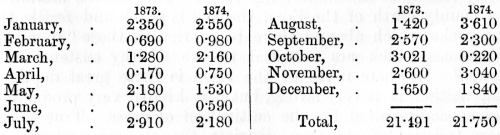

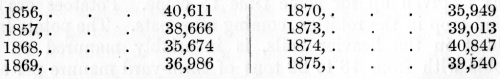

486,265 gallons to the acre. The following table shows the rainfall during

each of the twelve months of 1873 and 1874 at the Fife and Kinross

District Lunatic Asylum, near Cupar:—

Geology—Soils.

That well-defined valuable

group, the Carboniferous system, lying in the geological table of the

earth's crust, between the Old and New Red Sandstone, is the formation

that abounds in Fifeshire as in extensive portions of the Lothians and the

south-west of Scotland. The system, however, is not by any means intact in

the county. In almost all the Dunfermline and a considerable portion of

the Kirkcaldy district it abounds pretty exclusively. Here the coal

formation is extensive and very rich, and affords a valuable contribution

to the coal supply of our country, while it makes the west of Fife one of

the busiest centres in the "Land o' Cakes." Ironstone is abundant in

several parts of the county, and is extensively quarried at Oakley and

other works in the Dunfermline district. Lead was at one time quarried out

of the Lomond hills.

With the exception of a

narrow band running from Dunfermline to Dunino, near St Andrews, the

eastern and northern portions of the county are almost entirely destitute

of coal. On the high lands in the parishes of Cameron, Ceres, Kettle, and

Falkland, and along a ridge in the direction of Dunfermline, the

carboniferous limestone exists in great quantities, and is worked

extensively. The soil on the section of the county north of the valley of

the Eden lies on those felspathic igneous traps that are so often

connected with the Old Red Sandstone. This formation, however, does not

exist to any great extent, being confined chiefly to the valley of the

Eden, where the upper or yellow group abounds. Freestone of considerable

value is quarried at various points. Dura Den—a romantic ravine in the

neighbourhood of Cupar—is peculiarly rich in those fish fossils so

characteristic of the Old Red, and has engaged the pen of many of our most

talented geologists who have paid it a visit hammer in hand, eager to

possess some of its fossilised treasures. With all this variety of rocks

and formations throughout the county, the soil of the various districts

necessarily differs considerably, the character of the soil being

generally dependent upon the chemical condition of the rocks that underlie

it. In a few hollows on the north-west alluvial accumulations form the

soil, but with these exceptions the soil of the different districts

corresponds pretty closely to the underlying rocks. Thus in the section of

the county north of the Eden the soil is quick and fertile, the trap rocks

which abound there being rich in those "inorganic substances which are

essential to the healthy sustenance of plants." Nowhere north of the Eden

is there great depth of soil, neither is it very strong, but it is kindly,

very productive, and specially suited for the cultivation of grass. True

to the characteristics of the trap districts, the scenery and surface

north of the Eden presents great diversity—numerous irregular mounds and

many waving valleys. The soil that overlies the Carboniferous system is

generally composed of cold retentive clays and decomposed bituminous

shales, and is seldom fertile or easily cultivated. This rule still holds

good in several parts of Fife; but the advanced system of farming—the

extensive draining and the heavy manuring—of the past fifteen or twenty

years, have immensely improved the natural properties of the soil, have

changed much of it into fertile land. The Howe of Fife or Stratheden,

comprising both sides of the Eden up as far as Cupar, has rich fertile

soil, parts of it being exceedingly productive. South of the Eden the land

rises gradually until it reaches, in the parish of Cameron, an elevation

of upwards of 600 feet. On this high land the soil is cold and stiff and

of a clayey character, with a mixture of lime. Around Ladybank the soil is

very light and shingly, and presents signs of having been swept off its

richest earthy coating by a current of water. The land on the rising

ground in the parishes of Collessie, Monimail, Cults, and Kettle is

considerably heavier and more valuable than in the valley of Ladybank. In

the neighbourhood of the Lomonds the soil is light, but sharp and valuable

for grass, while similar remarks apply to the high land of Auchtermuchty,

Leslie, and Kinglassie. In the parishes of Death, Auchterderran, and

Ballingry, the land is principally cold and stiff; but several very

excellent highly-cultivated farms are to be found in these parishes. A

good deal of the land on the north side of Dunfermline is composed of clay

of a strong retentive nature, while on the south the soil is chiefly thin

loam, with a strong clayey subsoil. In the parishes of Saline, Torryburn,

and Carnock the soil is mainly a mixture of clay and loam, and is

generally very fertile. All along the coast the soil, though variable in

composition, is rich and productive. The "Laich of Dunfermline" has a

strong clayey soil, somewhat stiff to cultivate, but on the whole very

fertile. The soil on the coast from Inverkeithing to Leven varies from

light dry to strong clayey loam, rendered extremely fertile and friable by

superior cultivation. About Largo the soil is deep rich loam, and produces

magnificent crops of all kinds, while in Elie it is light but very

fertile. Along the east coast the soil is deep and strong and very

productive, consisting chiefly of clay and rich loam. Speaking generally,

very little hindrance is afforded to tillage by rolling stones or

upheavals of rock, but here and there all over the district, sloping down

from the heights in the parish of Cameron to the Firth of Forth, beds of

water-worn boulders are met with. These boulders, lying in beds or rows

from north-west to south-east, belong to the metamorphic rocks, and were

brought thither doubtlessly by floating icebergs during the glacial

period. In the neighbourhood of St Andrews the soil is by no means heavy,

while the section lying north-east of Leuchars village is sandy and very

light, especially on the east coast, where a large tract of land known as

Tent's Moor is wholly covered with sand, and almost useless for

agricultural purposes. In Forgan and part of the parish of

Ferry-Port-on-Craig, the soil, though light and variable, is kindly and

fertile. On the farm of Scotscraig there are a few fields of very superior

land.

The Progress of the past

Twenty-Five Years.

The total acreage reclaimed

in Fifeshire since 1850 is very small, almost every suitable tract of land

having been brought under the plough long before that time. The spirit of

improvement dawned early on the county of Fife, and hence all the

important reclamations date much further back than the range of this

report. In dividing and squaring up fields during the past twenty-five

years, many small patches and out-of-the-way corners that previously

produced only rough pasture have been made into cultivated land, while

around the base of hills on the borders of Kinross a few fields have been

reclaimed partly from moss and partly from strong pasture land. Draining

of course was the first operation in all those improvements, the stronger

land being trenched to a considerable depth. But though the acreage is not

greatly increased, the progress of the past twenty-five years has

nevertheless been very great. Those who recollect the state of agriculture

previous to 1850 can trace in the farms of the present day many wonderful

improvements. In fact, though a few of the older farmers still retain many

of the ancient customs,—customs that will in all probability die with

themselves,—it may almost be said that an entire change in the system of

farming has taken place in Fife during the past quarter of a century. The

science and practice of agriculture have of late years been receiving

considerable attention from a large section of the Fifeshire farmers, and

in the increased productiveness of the soil the result is showing itself

more and more strikingly every year. The expenditure for improvements

since 1850—and it has been very large—must be noted mainly against

draining, building, and fencing. Having been naturally very wet and

swampy, and next to useless in its original state, the greater portion of

the land was thoroughly drained early in the present century. Naturally,

however, these drains, never perhaps of the first order, required mending

after having done good service for perhaps a nineteen years' lease; and

during the last twenty-five or thirty years, almost the whole of the

county has been redrained.

A great deal has been done

since 1850 in the way of improving the buildings in the county. The

farmer's dwelling-houses have been immensely improved, while a very large

number of as fine farm-steadings as are to be seen anywhere in Scotland

have been erected. A very considerable amount of money has also been spent

in the erection of labourers' cottages. Almost every farm of even moderate

size in the county is now provided with servants' cottages of the most

approved construction, and we are inclined to think that in the matter of

house accommodation for the labouring classes, Fifeshire stands second to

no other county in the kingdom. An immense stretch of fencing has also

been erected since 1850; but still much, very much, remains to be done in

this respect. Ring fencing is pretty complete, but there is a great want

of interior or dividing fences. Every successive year, however, adds

greatly to supply this much-felt deficiency, and before many years have

past, it will in all probability be fully supplied. The true character or

real value of these, and all similar improvements, must of course be found

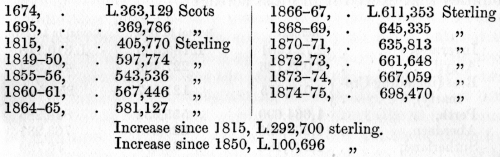

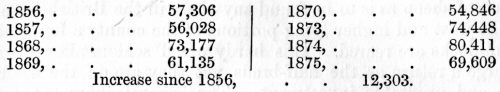

reflected in the rent-roll; and thus the following table of the total

valuation of the county (exclusive of railways and burghs) at various

periods since 1674 will be noted with interest:—

An increase during the past

twenty-five years of L. 100,696, or an average of close on L.4036 a-year,

is very creditable indeed, though it may not quite compare with the rise

in the rental during the same period in some other counties, especially in

the northern regions of Scotland. It must be kept in mind that, as already

stated, and as borne out by the table of figures just given, the principal

reclamations and improvements which go to increase the valuation of a

county were executed in Fife previous to 1850, while in these other

counties it is chiefly since then, or shortly before that date, that those

operations were carried out. The considerably greater increase during the

past half century in the value of grazing land, compared to arable land,

has also tended to retard Fifeshire in the general advance of rental.

Some half a century ago the

county of Fife occupied a slightly higher position than it does now in the

comparative valuation list of counties of Scotland. Its valuation for its

acreage, or say its valuation per acre, compared with that per acre in the

other thirty-two counties in Scotland, was slightly higher then than now.

Not that Fifeshire has been receding or sluggish in the race, on the

contrary it has been gradually and steadily moving onwards, but other

counties (taking up the good work begun by the farmers of Fife and

southern agriculturists generally, and carrying it on, too, with all that

spirit and zeal so characteristic of our Scottish farmers) have been

gaining ground upon it. Fife stands seventeenth among the Scottish

counties with respect to gross acreage, six—Inverness, Argyll, Ross,

Perth, Aberdeen, and Sutherland— being close on four times its size; while

other four—Dumfries, Ayr, Lanark, and Kirkcudbright—are nearly twice as

large. In 18.15 Fife occupied the proud position of fourth highest in

Scotland with regard to valuation, the three higher counties being Lanark,

Perth, and Ayr, while Forfar came fifth, and Aberdeen sixth. Now it stands

fifth, Aberdeen having not only made up to its spirited little rival in

the south (for little it may be called when compared with Aberdeen, a

county four times its size), but passed it by about L.17,158—a

comparatively small sum, however, taking into account the difference in

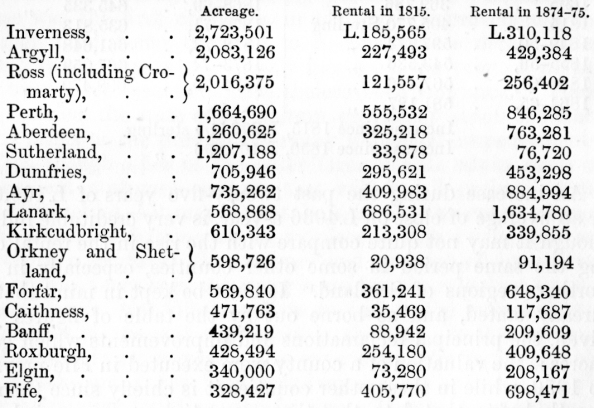

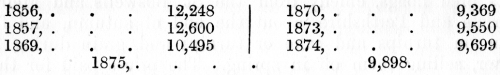

the size of the two counties. The following table shows the position Fife

occupied in 1815 and occupies now, in comparison with the sixteen counties

that exceed it in gross acreage:—

It will be seen from this

tabulated statement that Fifeshire's comparative position was a little

more prominently to the front in the early days of the present century

than now. It cannot be expected that a large annual increase of rental can

go on for ever at the same ratio. A certain point once reached, then the

increase must be limited; and we are of opinion that at 1815 the county of

Fife had attained a higher elevation in the steep hill of advancement than

most other counties between the Firth of Forth and John O'Groats. Hence

the recent apparent gaining of ground by these other counties. They have

done more than Fife, simply because they had more to do. The honour of

having the highest annual valuation per acre in Scotland belongs to

Lanark, but Fifeshire follows very closely. The total valuation of

Fifeshire for 1874-75, exclusive of railways and royal burghs, is equal to

no less than L.2, 2s. 6d. per acre, a fact that places the county in a

position of which it may well be proud. Of course Fifeshire has great

advantages by the valuable treasures of its rocks, but, after making all

due allowance for the rental of minerals and manufactories, the county

stands very high indeed in a purely agricultural point of view.

It is somewhat difficult to

ascertain exactly what the rise of the rent of arable land has been during

the past twenty-five years, but we think we are not far wrong in putting

it down at 25 per cent. From 1850 to 1860 there was a large increase of

rent on all farms, the rise in some cases amounting to as much as 50 per

cent. This large and very sudden increase was attributable chiefly to the

high price of grain and potatoes during the Crimean war. Almost every

year, from 1853 to 1867, potatoes at some time during the season reached

the high price of L. 5 per ton, and hence quite a potato mania arose in

the county. Potato land was rushed after, and fabulous rents paid for it;

and it is not too much to say that the step thus taken by a large number

of the Fifeshire farmers was the most unprofitable step that has been

attempted in the county during the last fifty years. Of this subject,

however, more anon. Since 1860 the value of clay land has considerably

decreased, owing to the low prices of grain for the crops of 1862, 1863,

and 1864, and since the latter year to the increased cost of labour and

other working expenses. One county agriculturist, whose opinion is

entitled to much consideration, assures us that "there is no increase in

the value of the rent of clay land as compared with the rents of 1850, but

that the rent of good green crop land has increased 20 per cent.;" and we

have met with several others who coincide in this opinion regarding the

clay land. We could point, however, to several clay farms that have been

slightly raised since 1850, but, speaking generally, the rise has not been

large. In fact, much of the clay land was so highly rented previous to

1850 that very little more could be added without "rack" renting the

tenants. During those few years that the Crimean war lasted the

competition for farms was so excessive that not a few were induced to

offer rents which they afterwards found themselves unable to pay, and thus

deductions had to be made in several cases, some before one half of the

lease was run. Had those fabulous prices that were paid for grain and

potatoes betweenl853 and 1867 continued, even the very highest rented farm

in the county would have proved a a most profitable speculation; but this

could not have been expected, nor, in fact, was it to be desired. During

the past ten years the increase in the rental in the Kirkcaldy district

has been no less than L. 42,516, while in the St Andrews district the

advance has been L.36,002. Manufactures and minerals have swelled the

increase in the Kirkcaldy district considerably; but in the St Andrews

district the rise is due almost entirely to an advance in the rental of

farms.- The Dunfermline district, the great mining centre of the county,

shows an increase of L.20,544, or about L.1500 more than the Cupar

district.

Modern Farming.

The system of farming that

obtains in Fife at the present day is, on the whole, of a most improved

description, and is quite abreast of the times; but before proceeding to

discuss the various farming customs, it may not be out of place to

introduce a few loose notes on a tour which the writer made throughout the

county. The starting point was Tayport, and the route—a waving one—along

the outskirts, ending where it began. It was in the "head hurry" of the

harvest, and all were busy in the fields. Cutting, a little more than half

finished, was proceeding with great rapidity in every direction, the

birring of the reaper being the prevailing sound. We visited several farms

along our course, and saw much to interest and instruct, much to admire

and little to find fault with. Close to Tayport, and situated on a slope

looking south-west, is the fine farm of Scotscraig Mains. It is the

property of Mrs Maitland Dougall of Scotscraig, is leased by Mr Peter

Christie, extends to 502 acres, and is rented at L.1210, being a rise of

about L.233 since 1864. Mr Christie, a gentleman of very extensive

experience in the valuation and cultivation of land, works the mains on

the seven-shift system of rotation, viz., 1st, oats; 2d, beans or

potatoes, or more frequently part of both; 3d, wheat; 4th, turnips; 5th,

barley; 6th, hay; and 7th, pasture. He breeds neither cattle nor sheep,

but buys in large numbers of both for the grass, and feeds them off in

winter with turnips and artificial food, of which latter commodity he uses

an immense quantity. The soil on the most of this farm is strong loam,

suitable for almost any kind of crop.

Leaving Scotscraig, and

proceeding along the north coast in the direction of Newburgh, we pass

through the parishes of Forgan, Kilmany, Balmerino, Creich, Dunbog, and

Abdie, at the northwest corner of which Newburgh is situated. In Forgan,

as all along this course, the soil is light but fertile. The principal

farms in this parish are Newton and Kirktonbarns, the former of which

extends to about 774 acres, and is leased by Mr George Ballingall, the

rent being L.1139. Mr Carswell, the proprietor of the estate of Rathillet

in Kilmany, holds the home-farm in his own hands. It extends to 643 acres,

and is valued at L.1132. The fine valuable farm of Wester Kilmany is held

by Mr Watt, and is rented at very close on L.3 per acre, or an increase of

a little over 12s. during the past ten years. The parishes of Balmerino

and Creich can boast of several extensive and very fine highly-cultivated

farms, the larger ones being Fincraig and Pitmossie, extending to 450

acres; Peasemills, measuring 348 acres; Carphin and Lutherie, 645 acres;

and Creich, 354 acres. The soil in the tract of land over which these

farms extend is very variable, as will be inferred from the fact that the

rents vary from L.l, 10s. to close on L.3 per acre. The little parish of

Dunbog, through which we next pass, contains a few large farms, but none

of them exceed L.2, 5s. per acre. The farm of Dunbar, leased by Mr John

Ballingall, extends to about 735 acres, the rent being L.910. Besides this

farm, Mr Ballingall holds several others, and pays in all between L.2400

and L.2500 of annual rent. He, like the majority of farmers in his

neighbourhood, works his farms chiefly in seven shifts, but occasionally

he takes three years' grass. He breeds and rears a large number of sheep,

while he generally owns about forty cows. He feeds very extensively, and

consumes upwards of L.1800 worth of cake every year. The soil in the

parish of Abdie varies very much, some parts of it being excellent, and

some light and very inferior. Perhaps the best farm in the parish or

neighbourhood is Park-hill, a valuable holding situated close to the royal

burgh of Newburgh. It extends to about 480 acres, and is rented at L.1420,

or an advance of about 16s. per acre since 1864, the tenant being Mr A. W.

Russell. Part of this farm lies on a low level, close on the banks of the

Tay. The fields next the river were reclaimed less than fifty years ago,

the present farmer remembering to have seen boats floating about where he

now reaps abundant crops. The soil is chiefly alluvial clay, part of it

being strong and deep. The rotation pursued on this level is eight

shifts—1st, oats; 2d, potatoes or beans; 3d, wheat; 4th, potatoes or

beans; 5th, wheat; 6th, turnips; 7th, barley; and 8th, grass. Turnips and

beans grow well, while wheat and oats grow fairly, and barley very well. A

considerable portion of the farm lies on a steep slope overlooking the Tay.

The soil here is light loam and black earth, and the rotation five shifts—

1st, oats; 2d, turnips; 3d, barley; 4th and 5th, grass. Mr Russell rears

about twenty-five calves from cross-cows and shorthorn bulls. He generally

feeds about fifty head of cattle every winter, buying in stirks or

two-year olds to supplement his own lot. An abundant supply of turnips is

liberally backed up by cake, and in the month of December Mr Russell often

sells at L.30 a-head. He is careful to buy in the best stock that can be

had, but still it is very apparent that the animals of his own • rearing

come out best in the feeding. Mr Russell has an excellent farm-steading

supplied with covered courts, and the two-year olds are kept in the house

all summer and fed on cut clover, the cows and stirks being grazed

outside.

Taking the train at

Newburgh we next land at Collessie, Passing on our way a number of large,

carefully-cultivated farms. The parishes of Strathmiglo, Abernethy,

Auchtermuchty, and Falkland, which lie on the west of the line, are very

irregular on the surface and variable in soil, the predominating kind

being light, friable, fertile loam. These parishes contain several very

large farms, rented at from L. 1 to L. 1, 15s. per acre. Close to the

Collessie Railway Station lies the compact valuable estate of Melville,

belonging to Lady Elizabeth Melville Cartwright. Mr Cartwright (Lady

Elizabeth's husband) is an enthusiastic, experienced agriculturist, and

the estate is a model of regularity and system. Considerable improvement

has been effected on the estate in various ways during the past

twenty-five years. A large breadth of very fine wood was cut down, part of

the land thus cleared being replanted and part reclaimed. One farm of 250

acres has been lined off and fenced. Of this, 100 acres were trenched at a

cost of about L.6 an acre, and having been put into regular rotation, the

farm was let to Mr Birrel for nineteen years at a rent of 15s. per acre

for the trenched land, and 3s. per acre for the unreclaimed land, which is

intended to be brought under cultivation immediately. Before the tenant

entered a new dwelling-house and farm-steading were built. The land is so

dry and porous that very little draining was required. Besides these

improvements Mr Cartwright has just erected about 12,000 yards of very

superior wire fencing. The posts and strainers are all unusually heavy and

strong, while the wire is of the best galvanised plaited description. The

wires are six in number, and are placed so as to keep in sheep. Mr

Cartwright has also erected a number of very superior labourers' cottages

throughout his estate, while at his home farm, which is under the able

superintendence of his factor Mr Andrews, he has most successfully

established a herd of polled cattle. Of the herd, however, more anon.

Adjoining his magnificent gardens Mr Cartwright has a neat little nursery,

into which he plants his young trees for a short time before planting them

permanently. The plants are brought in at the usual stage for

transplanting, but are put into the nursery for a short period to

strengthen the rootlets, a system that is found to be most advantageous to

the growth of the trees.

One of the principal farms

on the Melville estate is Nisbetfield, a very carefully cultivated

holding, lying in close proximity to Melville House, the ancient baronial

residence of the Leven family. The tenant is Mr Archibald, and the rent

about L.1, 7s. per acre, The soil generally is light loam, with a few

spots of clay. In our route from Melville towards Cupar we pass a number

of very excellent farms, large and well cultivated. In the parishes of

Dairsie and Kemback there are a few as fine farms as can be seen anywhere

in the county. About the centre of the latter parish, and close to Dura

Den— that classical spot so famous among geologists—lies the valuable

little estate of Blebo, the property of Mr Bethune, an agriculturist of

great enthusiasm, untiring energy, and considerable experience. Mr Bethune

works the home farm himself, and pursues a most advanced system of

farming. The soil is partly strong heavy clay, and partly deep able black

loam. He cultivates at a great depth, chiefly by steam, and manures well,

raising magnificent crops of all kinds, especially barley. He believes in

Mr Lawes' system of continuous barley growing, and intends giving it a

trial. The climate here is exceedingly mild and genial, and with such

fertile soil and good seed almost every grain of seed that is sown

germinates and produces a rich return. In 1873 he sowed one field with

only one and a-half bushels of barley, and had a very heavy crop yielding

seven quarters per acre, while last spring he sowed another with two

bushels, the crop of which happened to be in process of being cut when we

visited Blebo. It was extremely heavy, all laid, as thick on the ground as

it could well stand, and had the appearance of yielding from seven and

a-half to eight quarters per acre. Very fine crops of turnips and beans

are also grown here, while last year Mr Bethune had a small field of

carrots which yielded about six tons per acre, the price obtained for the

ton being L.6. Another small field was put under carrots last spring, but

they have not done quite so well, though they will yet afford a fair

return. The finely sheltered situation and the picturesque wooded policies

of Blebo fit it specially well for the rearing of stock, and Mr Bethune

has been well known for a number of years as a breeder of shorthorns,

while he breeds a few sheep and also rears or buys and feeds a large lot

of excellent cross cattle. The herd of shorthorns merits more than a mere

passing notice ; but this will be done when speaking of stock generally.

The scenery around Blebo is

magnificent, the view from the handsome mansion-house being one of the

finest to be had in the county. The Mains of Blebo, which adjoins the home

farm, is leased and very carefully cultivated by Mr Rintoul. The farm-steading

is large, commodious, and very convenient, and has admirably

well-constructed close courts. At the farm of Todhall occupied by Mr Bell,

and situated about four miles east from Cupar, one of the finest farm-steadings,

not only in Fife but even in Scotland, is to be seen. It was erected some

ten years ago by the proprietor, Mr Cheape, and when it is mentioned that

the cost was about L. 8000, some idea will be had of its character. At the

farm of Rumgally, belonging to Mr Welch, and also in this neighbourhood,

there is another very superior steading with roofed courts, though it is

not quite such an extensive one as that at Todhall. Leaving Cupar and

retracing our steps a short distance by train, we find ourselves next in

the parish at Kettle.

The farms at Ramornie and

Balmalcolm, extending to 435 acres and rented at L.1084, form the

principal holding in this neighbourhood, and are leased by one of the

leading agriculturist of the county, Mr William Dingwall. The six-shift

system, so general in the best grain-producing districts of the county, is

the rotation pursued by Mr Dingwall, but we understand that he

contemplates changing into seven shifts, taking two years' grass instead

of one as at present. The soil on these farms is partly heavy retentive

clay, partly light loam, and partly sand, and some parts moss. The heavy

clay and moss were troublesome to cultivate, and difficult to " make," so

as to allow the braird to come away properly, and some fourteen years ago

Mr Dingwall drove quicksand on to these parts, mixing the clay and moss

and the sand together. A whole field was gone over in this way, about 1000

loads being spread on every acre, and now the land, formerly yielding

indifferently, produces excellent crops of all kinds. The experiment was a

pretty expensive one, but Mr Dingwall expects to be fully repaid for his

outlay in a few years. He intends breeding a number of cattle as soon as

he can turn his farms into seven shifts, but for many years he has raised

only a few.

His cows are Galloways, or

first crosses between Galloways and shorthorns, and his stock bulls are

carefully selected from the best shorthorn herds of the day, Mr

Cruickshank, Sittyton, being frequently patronised. The calves are suckled

and fed off as two-year olds, when an average price of L.28 is generally

obtained. Mr Dingwall feeds liberally with turnips and cake, of which

latter commodity he consumes a very large quantity—about L.500 worth every

year. He takes parks in the grazing districts of the county, chiefly in

the neighbourhood of the Lomonds, and buys in stirks or two-year olds to

graze on them, but does not find the system a very remunerative one. He

thinks that the more profitable system would be to graze on his own farm.

He, like a large number of Fifeshire farmers, buys in half-bred hogs, and

feeds them on grass, turnips, and cake. He seldom sows beans, but plants a

considerable breadth of potatoes every year, and averages a return for the

market of four, five, to six tons per acre, the refuse being given to the

cattle. Oats range from five to seven quarters, barley from four to six,

and wheat from three to five per acre. The farm-steadings are good, the

cattle courts being covered, and very conveniently constructed. Mr

Dingwall keeps seven pairs of horses, and allots about sixty-two acres to

each pair. The farms of Ramornie and Balmalcolm were at one time very

liable to flooding by the overflowing of a small winding stream; but a

good deal of money has recently been spent in widening and deepening and

embanking the course of the water by neighbouring proprietors and Mr

Dingwall himself, and now no damage is suffered in this way. Proceeding a

little further on, and passing a number of large farms, we next visit the

home farm of Balbirnie, which the proprietor, Mr John Balfour of Balbirnie,

holds in his own hands. It extends to 378 acres, and is valued at about

L.1, 15s. per acre. The soil is strong and a little stiff, while the

climate is colder than in many parts of the county. Very few cattle are

bred here, or indeed on the whole estate, the majority of the farmers

preferring to buy in feeders to rearing them at home. A few shorthorns are

bred at Balbirnie, while at Balfarg a superior Clydesdale stallion and a

stud of mares are kept, Mr Balfour's tenants getting the service of the

stallion if desired. This, as might have been expected, has manifestly

improved the class of horses in the district, and Mr Balfour deserves much

credit for his liberality. The improvements on Mr Balfour's estate during

the past twenty-five years have consisted chiefly of draining and fencing,

and in providing more accommodation for the consumption of turnips and

straw than was required in the past century and in the first twenty-five

years of the present, when only about five or six acres of turnips were

grown on the largest farms in the county.

Taking the road once more,

and proceeding in the direction of Dunfermline, that busy commercial town,

famous as the burial-place of King Robert Bruce, we pass through the

parishes of Kinglassie, Auchterderran, Ballingry, and Beath. The mining

interest is very extensive in the district embracing these parishes; and

as mines and agriculture seldom flourish equally together, it could not be

expected that this would be the most valuable farming district of the

county. Nevertheless there are a number of large and very carefully

cultivated farms in these parishes. The soil is not of a very superior

character, while the climate is only moderately good; and thus the rents

are lower than in better favoured districts. A few of the farms are as

high as L.2 per acre, but, on the other hand, a large number are not much

beyond L.1. The principal farms in Kinglassie are Kininmouth, leased by Mr

Blyth, and extending to 452 acres, and rented at L.650; East and West

Pitteuchar, tenanted by Mr Gibb (who also holds Lochtybridge, a small farm

of about 100 acres), and extending to 434 acres, the rent being L.874, or

an advance of L.44 during the past ten years; and Fostertown, extending to

300 acres, and rented at L.442. The tenant of this latter farm, Mr Robert

Hutchison, and his father, have by improvements at their own expense,

raised its rent in little more than a hundred years from L.70 to the sum

above stated. Mr Hutchison is a very careful, liberal farmer, and expends

nearly double his rent in cake and manure every year. The farm of Dothan,

in Auchterderran, measures 424 acres, and is rented at L..612; while the

farm of Lumphinans in Ballingry extends to 803 acres, and is let at L.693.

Hilton, in the parish of Beath, is rented at L.375, a few pounds less than

in 1864, the extent being 460 acres.

Mr Henry Heggie leases a

valuable holding of 300 acres at the south corner of Beath, known by the

modern title of Mains of Beath. The soil is naturally good, and under five

years' liberal treatment from Mr Heggie, has improved immensely. The farm

is worked by four pairs of superior Clydesdale horses, the system of

rotation being the six shifts. Mr Heggie cultivates carefully, and manures

very heavily, and produces excellent crops of all kinds. His Swedish

turnips this year are very superior. They are regular and very large, and

look like affording a yield of from twenty-eight to thirty tons per acre,

a yield which Mr Heggie has produced more than once. In addition to a

large supply of farm-yard manure, they got six cwt. of artificial manure

per acre, viz., 1 cwt. of nitrate of soda, 3 cwt. dissolved bones, and 2

cwt. bone meal. Mr Heggie keeps eight or ten very superior cross cows, and

with these and a good shorthorn bull produces stock that invariably

carries the places of honour at the Dunfermline Cattle Show. He was-first

last two summers with two-year old cattle at this show, and had also some

prizes for sheep of his own breeding. He buys in calves to feed, and sells

them off when from sixteen to eighteen months old, at from L.21 to L.22.

For two-year olds-bred by himself he has frequently received as much as

L.36; while his hoggs generally bring about 50s. at the markets in early

summer. The houses on the farm are good, but fences-are very deficient. He

has drained a great deal at his own expense during the past five years,

and has now got it into excellent order. A few miles further west, and we

reach the thriving town of Dunfermline. In the parish which bears the name

of this town there is a large number of very fine farms, though the

Dunfermline district is equally as famous in the mining and manufacturing

as in the agricultural world. In the immediate neighbourhood of the town

there are several large holdings.

Little more than a mile

north of the town lies the farm of Ballyeoman, occupied by Mr Henry

Thompson. It extends to 212 acres, and is rented at L.329. The soil is

composed of clay, of a strong adhesive character, and the system of

rotation is the six shifts. Grain averages from five to six quarters, and

weighs—barley, 55 lbs. per bushel; oats, 42 lbs.; wheat, 63 lbs.; and

beans, 64 lbs. Mr Thompson cultivates well, ploughing stubble to the depth

of about nine inches, and lea seven inches, and manures equally well. Tor

turnips, he gives twenty tons farm-yard manure, three cwt. Peruvian guano,

and two cwt. dissolved bones per acre; and for potatoes about twenty-five

tons of farm-yard manure, without any artificial stuffs. He keeps a few

cross cows, and rears calves from these and shorthorn bulls. He buys in a

large number, however, sometimes Irish, and sometimes home-bred cattle.

The homebred cattle, as with other farmers, invariably thrive best. Mr

Thompson sells off his fat animals in the months of April, May, and June,

and receives from L.26 to L.30 a-head. Sometimes from three to four score

of sheep are wintered on the farm, and a good stock of excellent

Clydesdale horses is kept. The houses and fencing are good. Since Mr

Thompson entered the farm, a few years ago, he has effected extensive

improvements at his own expense. He has made 2000 yards of road, erected a

turnip shed, and two covered cattle courts; has cleared out 1000 yards of

old hedging, in order to enlarge and square up fields; has planted some

new hedges, built 1600 yards of stone and lime dykes, and drained about

thirty acres of land. The drains were cut about three feet deep and

sixteen feet apart.

Mr Thomas Crawford holds

several farms in the neighbourhood of Dunfermline. He resides at

Pitbauchlie, and is an experienced, careful farmer. The soil on his farms

is mostly thinnish loam, with a clayey subsoil. On part of his holdings he

pursues the six-shift system, but on a large portion he has no regular

rotation. Wheat generally yields about four quarters per acre, barley

five, oats six, beans four and a-half, turnips twenty tons, and potatoes

eight tons. He manures heavily, giving twenty-five tons of farm-yard

manure and four cwt. of guano, or dissolved bones, per acre for potatoes,

and fifteen tons farm-yard manure, with three cwt. dissolved bones and two

cwt. of guano, for turnips. He breeds no cattle, but buys in a great many,

partly to graze and partly to winter. About the autumn he usually buys in

a number of half-bred ewes, and takes a crop of lambs off them, feeding

both the ewes and the lambs, and sending them to the markets. He also buys

in a few half and three-parts bred lambs towards the fall of the year, and

feeds the latter on turnips, while the half-breds are kept for grazing the

following summer. His farms are well-stocked with strong young Clydesdale

horses. The fences and houses are bad, but the drains are in good order,

having all been renewed by Mr Crawford at his own expense. He farms very

differently from almost all his neighbours, inasmuch as he grows very

little hay, and keeps a large portion of his land in pasture for three,

four, and five years. In the parishes of Carnock, Saline, and Torryburn

the soil, though not heavy, is friable and fertile, and the farms are

generally in a high state of cultivation. The system followed is very much

in accordance with that already noticed on such farms as Ballyeoman and

Mains of Beath.

Turning southwards from

Dunfermline, and proceeding towards Inverkeithing, we pass through a

highly fertile valley, known as the "Laich of Dunfermline." It bends down

to a very low elevation, part of it being only about seventeen feet above

the level of the sea. In this valley Cromwell is said to have fought one

of his many battles, and in the process of cutting drains, several horse

shoes were dug up from a depth of three or four feet, and it is affirmed

that these shoes belonged to the horses ridden by followers or enemies of

this immortal warrior. The farm of Backmarch, lying in this valley, and

extending to about 230 acres, is tenanted by Mr Mitchell. It is worked in

six shifts, and its soil is chiefly strong adhesive clay, some parts being

strong black loam. Mr Mitchell grows excellent crops of beans and good

crops of potatoes, while oats and barley grow fairly. Turnips were usually

very subject to damage by " finger and toe," but last season he tried an

experiment which has proved an entire remedy. When the field on which the

turnips were sown last spring was in grass, he spread a slight doze of

slack lime over it, and the turnips show no signs of disease, which he

attributes entirely to the action of the lime.

Within the memory of some

of the oldest inhabitants, a large stretch of the Laich was lying in a

swampy, spongy, unhealthy state; but now it is comparatively dry, and is

one of the best cultivated parts of the county. Mr Mitchell has redrained

a good deal of the farm during the past few years ; but still a few

patches are in want of better drainage. In some of the more retentive

parts of "the farm, there are only about fifteen feet between the drains,

and still the soil is not thoroughly dry. No pick is required in cutting

the drains, and a three-feet drain can be dug at 2s. per chain. Almost all

the old drains were laid with stones, but tiles are universally used now.

The rents of a few farms in this neighbourhood have been tripled since

1800, and doubled since 1830. Proceeding by Inverkeithing along the coast

to the picturesque little village of Aberdour, we pass a number of

extensive and very highly cultivated farms. On the large and valuable

estate of the Earl of Moray, in the parishes of Dalgety, Aberdour, Beath,

and Auchtertool, numerous and very expensive improvements in the way of

fencing, draining, and building have been effected during the past

twenty-five years. A few acres of new land have been added to two or three

farms in the parish of Beath; but the total acreage reclaimed since 1850

is not by any means large.

The road from Aberdour to

Burntisland winds along the coast through most charming wooded scenery,

forming one of the most delightful walks to be had, even in the

picturesque county of Fife, and during the summer and autumn months is the

favourite saunter of many hundreds of holiday seekers, who crowd the

rising little town of Burntisland. The soil on a good deal of the land

around Aberdour, and running down to the Firth of Forth, is not by any

means heavy, but it is friable and very fertile. The farms of Dallachy and

Balram form the principal holding in the parish of Aberdour. They extend

to about 600 acres, and are rented at L.1253, the tenant being Mr Thomas

Cunningham. The greater portion of the farm of Dallachy consists of strong

fertile soil, while on Bal-ram the land is chiefly thin loam. The heavy

land is worked in seven shifts, with two years' grass, while the light

land is worked in five shifts, one green crop, two grain crops, and two

years grass. Dallachy produces excellent crops, barley sometimes yielding

as much as eight quarters per acre, the average being about seven. Barley

generally weighs from 53 lb to 56 lb per bushel, wheat about 64 lb, and

oats from 42 lb to 44 lb. It is very seldom that much grain is lost here

by bad harvests, but in 1872 Mr Cunningham sustained a loss of more than a

year's rent by wet weather. Turnips grow well, and have never been finer

than this season. The farm-steading is good, while the dwelling-house is

excellent. Mr Cunningham recently commenced to rear calves from Galloway

cows and shorthorn bulls, and as yet the experiment has been satisfactory.

Moving a little further on

we come to the highly cultivated farm of Newbigging. It extends to 280

acres, and is leased by Mr Prentice, who holds besides it the farm of

Balbairdie, extending to 350 acres, and situate in the parish of Kinghorn;

of Bankhead, also measuring 350 acres, and situate in the same parish; and

Balgreggie, extending to 130 acres, and situate in Auchterderran.

Newbigging is all arable, and grows very fine crops. This year there are

25 acres under wheat, 82 under barley, 26 under oats, 25 under potatoes,

20 under turnips, and 25 under hay. The remainder is so hilly that it is

left lying in grass, and cultivated only when the pasture gives way. Most

of this farm is on limestone rock, part of it being heavy clay and part

fine friable turnip and barley land. Newbigging is situated close to the

Grange distillery, from which Mr Prentice obtains large quantities of

draff, which enables him to keep about 100 cattle and 300 sheep every

winter. This gives him such a command of manure that he can grow almost

any sort of crop without strictly abiding by any fixed system of rotation.

Balbairdie is mostly heavy land, and here Mr Prentice has a breeding stock

of half-bred ewes, and keeps the outside land in grass as long as

possible. Four pairs of horses are employed in cultivating this farm, the

system of rotation being—1st, oats or barley; 2d, turnips; 3d, barley or

wheat; and 4th and 5th, hay and pasture. Bankhead is all fine haugh land,

lying on trap rock. With the exception of a hilly field, which is kept a

year or two longer in pasture than the rest, the whole of this farm is

worked in seven shifts—1st, oats; 2d, potatoes; 3d, wheat; 4th, turnips;

5th, barley; 6th, hay; and 7th, pasture. Barley and oats yield from 5 to 8

quarters per acre, while wheat gives about 5 quarters. The return of

potatoes ranges from 7 to 8 tons per acre. The lea is ploughed 8 inches

deep, and broken up as soon as possible in March, and sown by a drill

machine with 2½ bushels per acre on the best land and with 3½ on the

inferior land. Mr Prentice generally manures his turnips with a mixture of

artificial manure entirely, but when farm-dung can be had he gives about

12 tons to the acre. Most of the potato land is manured on the stubble

with 20 tons farm-yard manure, ploughed to as great a depth as possible,

and seasoned with from 3 cwt. to 4 cwt. of guano and dissolved bones at

the time of planting. The stubble land is generally ploughed 10 inches

deep, and when the land is steep it is ploughed downhill, the depth of the

furrow being about 12 inches. Balbairdie has all been limed and drained

within the past twenty years at the expense of Mr Prentice, who has also

expended a large sum on buildings.

The farm of Balgreggie lies

10 miles inland, and is all under grass. A large number of the cattle

required for feeding in winter are grazed here, which saves Mr Prentice

from the necessity of buying in all his winter's stock at one time. The

farm of Grange, adjoining Newbigging, and close to the town of Burntisland,

is leased by Mr Walls, and is worked in six shifts. Mr Walls usually keeps

about 24 cows, and rears their calves, buying in stirks to supplement the

winter's stock at from L.14 to L.15 a head. When fat these animals are

generally sold at from L.20 to L.28. The soil is good, and good grain and

green crops are raised. About 200 hoggs are usually wintered on the farm,

and fed or sold off lean as the state of the markets may determine.

Leaving Burntisland and proceeding eastwards, through an extremely fertile

border of land facing the Firth of Forth, we rest a little at Kirkcaldy,

around which there are several very fine farms. In the parish of Kinghorn,

which we have just passed, lies one of the best managed little properties

in the county, that belonging to Mr William Drysdale of Kilrie. Mr

Drysdale is a spirited agriculturist, and feeds a lot of very fine cattle,

not a few of which do him much credit in the Christmas and other fat

shows. The system of farming pursued in the Kirkcaldy district is almost

identical with that already described on seaside farms, and therefore we

need not waste time or space in detailing it. In the parishes of Wemyss,

Scoonie, and Largo the farms are very variable in size. The soil is also

variable, and rents range from L.1, 5s. to L.2, 10s. per acre.

One of the finest farms in

Largo is Buckthorns, occupied by Mr Beveridge. The soil is principally

rich loam and fertile clay, and heavy crops both of grain and roots are

grown. On a field on this farm we saw when passing as fine a crop of oats

as we have ever seen anywhere. Inland, a few miles from Largo, principally

in the parishes of Ceres, Cults, and Kettle, lie the valuable estates of

the Earl of Glasgow. These estates are under the able and efficient

supervision of Mr M'Leod, banker, Kirkcaldy (brother to the late

celebrated Dr Norman M'Leod), who acts as factor in Fifeshire for the

noble Earl. Since 1850 the rental of these estates for farms alone has

increased by about L.1700, while the revenue to the landlord from

limeworks has advanced from L.318 to L.900 during the same period. The

limestone is of the white variety, and when burned produces lime of very

superior quality. The demand for it is yearly increasing, large quantities

being exported out of the county. , Extensive improvements have been

effected of late in the way of draining and building, and though the rise

in the rental is pretty high, yet it does not afford a fair return for the

landlord's outlay. There is much need for more fencing on these as on all

other estates in the county, but the buildings generally are good; and

arrangements have been (or are being) made for the erection of several new

steadings and cottages. On some parts the soil is strong clay and on

others light loam. The five-shift rotation obtains for most part, only a

very small breadth of potatoes being grown.

Continuing our eastern

course, and as we approach the famous "East Neuk," we enter, perhaps, the

finest agricultural district of the county. The land all over the East

Neuk, though a little strong and retentive in some parts, is sure and very

productive, and is rented at high figures, some of it as much as L.4 and

L.5 per acre. One small patch, in fact, brings in to its fortunate

proprietor the enormous and almost unequalled rent of about L.8 per acre.

The estates of Balcarres, belonging to Sir Coutts Lindsay, Bart; of

Balcaskie, the property of Sir B. Anstruther, Bart., M.P.; Kilconquhar,

belonging to Sir John Bethune, Bart.; of Charleton, the property of Mr J.

A. Thomson; Gilston, belonging to the heirs of the late Mr Baxter; and

Gibliston, belonging to Mrs Gillespie Smyth, and situated chiefly in the

parishes of Kilconquhar, Elie, Abercrombie, and Carnbee, are under the