|

THE MANAGEMENT OF OAK

COPPICE-WOOD. CAUSE OF DISEASE AMONG LARCH FIR PLANTATIONS. HOW TO FIND

THE VALUE OF YOUNG PLANTATIONS AND OF FULL-GROWN TIMBER TREES. A FEW

PRACTICAL REMARKS RELATIVE TO THE MANNER IN AVHICH WOOD OUGHT TO BE

PREPARED FOR PUBLIC SALE.

SECTION I. THE MANAGEMENT OF OAK COPPICE

Plantations of the

description termed oak coppice, are now so common in Scotland, that

there are few landed estates of any considerable extent upon which there

is not less or more of them. In the West Highland counties there are

many extensive plantations of oak coppice; and within the last thirty

years many fine old oak forests have been cut down in the midland

counties which also are, for the greater part, now converted into

plantations of this description—the same being trained up from the young

shoots which have arisen from the stocks of the old trees which were cut

down. And seeing that this description of wood crop is upon the increase

upon the estates of landed proprietors, I consider that it may not be

out of the way for me here briefly to detail the best modes of

management of the same, more particularly with the view of pointing out

the most profitable manner of going to work in the converting of old oak

forest ground into healthy young coppice-wood.

When a plantation of old oak-trees is cut down, and when it is the

Intention of the proprietor to convert it into an oak coppice-wood, for

the purpose of raising a crop of oak bark upon the ground, after the old

wood has been disposed of, the work must be proceeded with in the

following manner :—First, the whole of the wood of the old original

trees, when cut down, should be removed immediately, as also all the

bark taken from them — and this, in order that no damage may be done to

the young shoots as they arise from the newly-cut stocks; for, if the

wood be allowed to lie long upon the ground after it is cut, the young

shoots will have grown to a considerable height, and they, being

extremely tender, will be easily broken in the act of removing the wood

at a late period. Therefore, in order to prevent this state of things

taking place, if the wood have been sold to any neutral person, say

about the 1st of May, he should be bound by the articles of sale to have

the whole of both wood and bark removed by the 1st of July at the

latest; and if this be not done, much loss will no doubt be sustained in

the after crop of the coppice-wood, seeing that it is impossible to

remove heavy timber from the ground without rolling it over the suckers

in their tender state.

This part of the work is always best done by the proprietor’s own

servants, and under the superintendence of an experienced forester;

because in such a case, the people who cut the wood are paid by the

proprietor, and being so, will look more to the interest of the work, or

at least will attend more to the orders given them, than strangers from

a distance would do, whose only interest is that of getting the wood cut

down at as little expense as possible, without any regard to the future

value of the plantation. It is also necessary to notice here, that in

cutting down any large oak tree, the stock of which is intended to push

up young shoots for the formation of coppice, great care is necessary to

see that the bark is not injured below that part where the tree is cut

over; for if the bark be hurt and ruffled there, so as to separate it

from the wood, moisture will be lodged between it and the wood, and

consequently a rot at that part will be apt to take place. In order to

prevent this, it is always a good plan, previous to commencing the

operation of cutting down the trees, to employ a cautious trustworthy

man to go before the woodcutters, who, with a hand-bill and wooden mell,

should be instructed to cut the bark right through to the wood, in the

form of a ring all round the circumference of the tree, just about three

inches above the surface of the ground. This first ring being cut all

round the bottom of the tree, three inches above the surface of the

ground, another should be made in like manner about twelve inches higher

up on the boll of the tree, when the piece of bark situated between

those two cuts can be removed, and the woodmen made to saw each tree

across exactly by the lower mark, or bottom of the peeled wood; this

forms a guide to the men not to injure the lower part left with the bark

upon it, as well as, when any difficulty is experienced in bringing the

tree down, avoiding all waste of bark.

As soon as the wood and bark have been removed from the ground, all

rubbish and useless underwood should be carefully cleared away,

excepting any young healthy shoots, or young plants which may be

considered worth leaving upon the ground with the view of their

ultimately becoming trees. And immediately after the ground has been

cleared of rubbish, the stocks or stools of the old trees will have to

be dressed with the adze, in order to cause the young shoots to come

away as low down, and as near to the surface of the ground as possible.

If the young shoots of the oak, which are intended to grow up into

coppice, be allowed to proceed from that part of the old stock which

rises two or three inches above ground, these shoots will always partake

more of the character of branches than of trees, and never will make a

valuable plantation; but if the shoots be made to eome away from that

part of the stock where the roots join with the main stem, and which

lies immediately under the surface of the soil, they will partake of the

character of trees, and independent of the nourishment that they will

receive from the parent stock, they will also send out roots of their

own, and derive nourishment from the common earth, and form pretty large

trees if desired. Now, in order to cause the young shoots to issue from

this point, the long grass should be all cleared away round the stock,

and itself dressed off with an adze. In executing this, care must be

taken that the part where the roots issue from the main stem be not

injured; but supposing that three inches of wood have been left above

ground upon the stock, the workman will commence by levelling his tool

upon it fully two inches down upon the wood, and hew off this part all

round, gradually lessening the depth of his eut as he nears the centre

or crown of the stock, which is left untouched, thus leaving a fall from

the crown of the stock to its circumference of fully two inches, and

forming a convex crown. This form prevents the lodgment of moisture, as

well as causes the young shoots to come away as near to the earth as

possible, which should always be aimed at; and in this manner, each and

every stock which may be intended for the rearing up of coppice-wood

should be managed. The sooner that the operation is done after the trees

are cut, the better is the hope of a good crop of healthy shoots;

therefore, the forester ought not to delay this until all the other work

of clearing away the trees and rubbish he finished; the whole of the

work ought indeed to be gone on with according to the time that I have

above stated, but still, the whole may be proceeding simultaneously. My

way of proceeding with work of this kind is:—I have a party of men with

horses and carts, who begin upon one side of the ground, and clear away

all the valuable wood as they proceed, which is delivered to the sawyer,

or otherwise as the case may be: immediately following this first party,

I have a second, consisting of women and boys, headed by a man to

superintend them, who gather up all the rubbish that is left by the men

with the carts, and carry it to convenient openings, and burn it at

once, unless some other more valuable use can be made of it: the ground

being cleared by this second party, I have a man, or men if the grounds

be extensive, following them dressing the stocks in the way

described;—and in this manner the whole work can be made to go on at

once without losing any time.

If the stocks of the old trees which were cut down are not numerous upon

the ground, as is more than likely to be the case if the trees were of

any considerable age, there will not be enough for a permanent crop upon

the ground. If, for instance, they were eighty years old, there will not

be more than one hundred and twenty trees to the acre, making them about

twenty feet one from another. Now, to have a piece of forest ground with

that number of stocks upon it to the acre, would never pay the

proprietor the common rent of his land : therefore, in order to take

advantage of the ground forming the vacant spaces between the stocks,

and to make the whole pay ultimately as any other plantation would do,

the ground should be properly drained wherever found necessary, and a

crop of young oak-trees planted all over it wherever there is room. In

this case, the young oaks which may be put in, together with the old

stocks, may be made to stand, as nearly as possible, eight feet apart:

and again, all the intermediate spaces between them should be tilled up

with larches, so as to make the trees over the whole plantation stand

about four feet one from another; that is, taking the old stocks into

account also.

By filling up the ground in this manner, the old stocks will ultimately

become of more value than if they had been left in an exposed state; and

again, from their growing more rapidly than the young trees, they will

produce shelter to the latter in their young state; so that, putting the

whole together, a plantation of this kind grows more rapidly than one

altogether planted with young trees.

When the young shoots from the old stocks have been allowed to grow

undisturbed for two years, they should then be carefully looked over,

and all small ones removed, leaving the strongest all round the

circumference, not closer than six inches one from another : these again

should be left for other two years, when a second and final thinning

should be made, choosing the strongest and healthiest shoots to remain,

and in no ease leaving more than six shoots to stand as a permanent crop

upon any individual stock, or fewer still if the health and strength of

the parent require it.

I am aware that many foresters are in the habit of not thinning their

oak stools at all, until such time as the shoots have attained a large

size, when they thin them out and peel the bark from them, supposing

that by this system there is a gain from the sale of the young bark

produced. Now, as regards this system, I am quite of a contrary opinion;

for, when the shoots are thinned out as I have advised, they very

quickly attain a large size, whereas, when they are not thinned out

until a late period of tlicir growth, the shoots become stunted, and

shortly indicate a want of vigour in their constitution ; consequently,

at the end of a given number of years, instead of an advantage being

gained by letting the shoots grow up until they are fit for peeling,

there is a decided loss. I have compared two plantations which were

managed upon these two different systems, and found the one managed upon

that which I have recommended, at the end of twenty years, worth nearly

a half more than the one managed upon the opposite system.

When the young trees have received their second course of thinning, as

has been pointed out, they should at the same time receive a judicious

pruning, and that in the same manner as has already been recommended for

the pruning of young oak trees : the larch firs, as they grow up, should

be thinned away by degrees, in order to give room to the oaks as they

advance, whether that may be to relieve the old stools or the young

trees; and in every respect this thinning of the firs should be done as

has already been recommended for the management of oak plantations

generally.

Seeing that the value of oak bark has fallen so much during the last

twenty years, I do not consider the [growing of oak coppice so

profitable a crop as it has been. About twenty-five years ago, the price

of oak bark was £16 per ton, while this year (1847) the highest price

that has been given in Edinburgh is £5, 10s.—making its value at the

present time only about one-third of what it was twenty-five years ago,

and consequently reducing the value of oak coppice plantations in the

same ratio; and, upon this consideration, I do think that proprietors

should not, at the present time, rear up oak plantations with the

intention of converting them into coppice, as has in many instances been

done of late. I have seen plantations of healthy oak trees, about

thirty-five years of age, cut down for the sake of the bark they

produced, and with the view of converting them into coppice-wood, so as

to have a crop of hark every twenty-five years afterwards. Now, had

those trees which were cut down at thirty-five years of age, been

allowed to grow for other forty or fifty years, they would, of course,

have attained their full magnitude, and been worth to the proprietor, at

the end of that period, more than three times the money that he could

get as the produce of the same plants if cut down and disposed of in the

form of coppice-wood, at periods of twenty-five or thirty years.

The safest and the best plan, with regard to all plantations, is, to

allow the trees to attain their full magnitude in the usual way, when

the timber will in all cases find a ready market, and at a fair price.

No doubt, where old plantations are cut down, it is right and proper

that the stocks of them should he converted into coppice-wood; for this

is taking advantage of growths which can be converted into use, and

which would otherwise he lost; hut to raise up trees to a certain age,

and then cut them down prematurely for the sake of their hark, is, at

best, an enormous loss to the proprietor, as well as to the country in

general.

SECTION III CAUSE OF

DISEASE AMONG LARCH FIR PLANTATIONS IN SCOTLAND.

It is my opinion, that

there is no tree cultivated in Britain more worthy the attention of

landed proprietors than the larch. I am not aware of any purpose for

which oak is now used, for which larch would not answer as well. It is a

rapid-growing tree, and attains maturity long before the oak. I have

seen larch trees, little more than thirty years old, sold for 60s. each,

while oaks of the same age, and growing upon the same sort of soil in

the same neighbourhood, were not worth 10s. each; and this at once

points out the advantage of planting larch where immediate profit is the

object. The larch has been held in high estimation in former times, as

we learn from several old authors. The first mention made of the

cultivation of this tree in England is by Parkinson, in his “Paradisus,”

in 1629; and Evelyn, in 1664, mentions a larch tree of good stature at

Chelmsford, in Essex. It appears to have been introduced into Scotland

by Lord James, in 1734. But the merit of pointing out to the proprietors

of Scotland the valuable properties of the larch as a timber-tree for

our climate, appears to be due to the Duke of Athol, who planted

it at Dunkeld in 1741. The rapid growth of these, and of others of the

same species, afterwards planted in succession by that nobleman, as well

as the valuable properties of the timber of the trees that were felled,

realised the high character previously bestowed upon the larch by

foreign and British authors, who were followed in their opinion by

others, such as Dr Anderson, Watson, Professor Martyn, Ncol, Pontz,

Lang, and Monteith—all confirming, and further extolling, the valuable

properties of the tree. It is 110 wonder, therefore, that the larch has

been planted so extensively in Scotland of late years, in almost every

kind of soil and situation, and under every variety of circumstances

capable of being conceived in forest management, seeing that its culture

has been so much recommended by men in whose opinions landed proprietors

put much confidence as regards forest matters. I say that it is in a

great measure owing to the advice of such men as 1 have above named,

that the larch has been so extensively planted within the last fifty

years in Scotland. According to their opinion, it was one of the

hardiest, and most easy of culture, among our forest trees; and

proprietors, relying too implicitly in this matter upon the soundness of

the opinions of such authors, planted larch too indiscriminately, upon

all kinds of soil, without having due respect to the nature of the tree;

for the larch, as well as every other tree, is influenced by a natural

law, which restricts it to particular states of soil, in order to

develope itself fully and perfectly; and it is upon this point that the

cause of the disease now so prevalent in the larch rests. It is well

known that, in many instances, whole plantations of larch trees have

died, I may say almost suddenly; and, in many instances, plantations of

it have failed in making a return of the expected advantages, far

inferior even to the Scots fir.

For some years past, much has been said and written relative to the

nature and cause of that disease, now so prevalent among our larch

plantations, generally termed the heart-rot, or, as some writers term

it, dry-rot (merulius destructor); but, for all that has been written

upon the subject, I am not aware that any thing as yet really

satisfactory has been the result, at least in so far as to cause any

likelihood of a really permanent improvement in the cultivation of the

tree for the future : therefore, in consideration of this, I may here be

allowed to give my opinion, as a practical forester, of the cause of a

disease which appears still to prevail extensively among the most useful

of our timber trees. Many who have written upon this most important

subject assert that, from the circumstance of the larch not being a

native, it is fast degenerating in our country; and, in illustration of

their argument, they point out the healthy development of many old

original specimens yet remaining in different parts of the country. Such

a weak argument as this is scarcely worthy of being confuted ; for we

may as well say that the plane tree, which is not a native of Scotland,

ought to be fast degenerating also, which wo know is by no means the

ease. Another argument against this assertion is, that in many places we

find healthy larch plantations, and in other places unhealthy, both,

nevertheless, being of the same age. Now, I would ask such as hold the

above opinion, if the larch be degenerating, why is it found to succeed

well in one place and not in another,—and that, too, even within the

bounds of the same gentleman’s property ? The only reasonable answer

that they can give to this question is, that, wherever the larch is

found thriving well, it must he growing in a state of soil agreeable to

its constitution; and wherever it is found not thriving, it must be

growing In a state of soil not agreeable to its constitution. Therefore,

in our further Inquiries after the cause of the rot in the larch, we

must first ascertain the nature of the circumstances which affect the

tree in both cases.

The larch is a native of the south of Europe, and also of Siberia. It

inhabits the slopes of mountainous districts, in the lower parts of

which it attains its largest dimensions. In its native mountains, the

larch is never found prospering in any situation where water can lodge

in the ground in a stagnant state; nor is it ever found of large

dimensions in any extensive level piece of country having a (lamp

retentive bottom or subsoil. Upon the other hand, the larch in its

native localities is found luxuriating upon a soil formed from the

natural decomposition of rocks; for there the surface soil rests upon a

half-decomposed stony subsoil, through which all moisture passes freely

in its descent from the higher grounds. In this state of tilings, the

roots of the trees always receive a regular supply of fresh and pure

moisture, and, at the same time, the ground in which the trees grow is

kept in a cleansed and sweet state, not having any stagnated particles

of gas or water lodging in it; and this forms, in my opinion, the

perfection of soil for the cultivation of the larch.

On making some inquiries at a gentleman who travelled among the

mountainous districts in Germany, where the larch is found in its native

state, I am informed that, upon level and dry-lying parts of the region

mentioned, the larch does not succeed well, being upon such parts always

more stunted in its growth, and apparently not enduring so long, as when

found with moisture passing freely among its roots; and this assertion

is exactly in accordance with the state of our larch plantations in

Scotland, for, wherever disease is found to prevail, there is either a

want of or too much moisture in the soil.

Now, until upon inquiry I was made aware of these circumstances relative

to the larch as found in its native localities, I never eould satisfy

myself as to the cause of the disease which has appeared among the larch

plantations in Scotland ; but since I have been made aware of the above

circumstances, and have compared them with examples of healthy and

unhealthy plantations upon several estates, where I have had the

opportunity of examining for myself, I am now perfectly convinced as to

the cause of the disease in question; and I am further convinced, that

any man who will compare the state of the ground upon which a healthy

plantation of larch is found in Scotland (that is to say, one which has

arrived at a considerable age, and is in a sound state) with what I have

stated relative to the healthy state of trees of the same species as

found in their native regions, will at once see the same circumstances

acting in each case. Thus :—In all eases of healthy larch plantations in

this country, where the timber has attained large size, and is sound in

quality, we find them growing upon a soil through which the water that

may fall upon it can pass away freely; as for instance, upon the slopes

of hills, and even in hollows, upon a strong clay soil, but where there

is a proper drainage for the ready and free passage of the superfluous

water; and I have even cut down larch timber, of large size and sound in

quality, growing upon a light sandy moss, two feet deep, which rested

upon a stiff clay. In this case the moss was drained, and the water

passed freely through the light soil; and the situation being upon a

slope, there was a continual circulation of moisture passing along upon

the top of .the sub-soil, or clay. In short, I have found good larch

timber growing upon almost all varieties of soil; hut I never found it

upon one which had not its particles constantly cleansed by the

continual circulation of water passing through it, either by natural

advantages or by artificial drainage. Upon the other hand, in all cases

of diseased larch plantations, where the trees have become stunted and

rotten in the hearts prematurely, we will find that the soil has either

been badly drained, or not drained at all. There must be ingredients

lodging in the soil, which act against the health of larch trees growing

upon it, and which can alone be carried off by an effective system of

drainage, in order to make it fit for the healthy rearing of larch.

In a plantation on a level piece of ground upon the estate of Arniston,

I had occasion to cut down some larches, in the way of thinning; the

plantation is about forty years old, and consists of a mixture of larch

and Scots firs. Upon cutting a number of larch trees in the central

parts of this plantation, I found them without exception all rotten in

the heart, which was exactly what I anticipated, for the soil had never

been drained; and upon cutting some trees upon one side of the

plantation which formed a sloping sandy bank, I found every tree sound,

and of excellent quality of timber; while at the same time, every tree

in this position was at least three times as large as those planted in

the interior level parts of the plantation, although all were of the

same age. Now, the cause of this superiority of the trees which grew

upon the sloping bank may at once be seen, from what I have already said

upon the point. Again, another side of this plantation was bounded by a

deep ditch, forming a fence upon the edge of a held ; and all along this

ditch upon the side of the wood, larch trees of excellent size and

quality were growing. Nothing can be more convincing than this, that in

order to grow larch timber of sound and good quality upon land which

formerly grew diseased trees, all that is required is to drain it, when

success will be the result.

I have always found larch trees succeed better when growing among

hard-wood trees, than when growing by themselves, or among other hrs,

even although planted upon soil in the same state in both cases; and the

cause of this, I conceive, to be that the roots of the hard-wood, from

their penetrating deeper into the earth than those of the fir, have a

tendency to divide the soil, and open it up for the more ready

circulation of the water through it. It is, indeed, well known to almost

every forester, that the roots of the hard-wood trees will penetrate

through the stiffest soil, and considerably break up and improve it, to

the depth of about two feet; and when the trees are of any considerable

age, with their larger roots spreading far and wide, I have often seen

the water running along the beds of such roots in considerable

quantities, showing that they acted as conductors for the water though

the soil: it is to this, that I attribute the superior health of such

trees found growing among liard-wood, as compared with those among their

own species upon the same quality of ground.

Upon the south lawn, at Arniston House, there are about twenty larches

yet growing, of very large dimensions. They are generally above eighty

feet high, and a few of them contain upwards of a hundred cubic feet of

timber; one in particular contains one hundred and fifty cubic feet, and

the tree is apparently in good health. The soil upon which these trees

are growing, is a light sandy loam of about fifteen inches deep, and

resting upon a stratum of yellow sand; they are, as nearly as I could

calculate from the appearance of one which was cut down lately, nearly

one hundred years old, and must have been among the first of the species

which were planted in the lowlands of Scotland.

These fine specimens are growing among older hard-wood trees, as tall as

themselves, but probably at least twenty years older. My opinion is,

therefore, that the hard-wood trees had been a considerable length

before the larches were planted among them; and owing to this

circumstance, the ground would be well prepared by the roots of the

hard-wood for the reception of the larches; which must, in a great

measure, be the reason that most of our original specimens are the

finest trees of the kind at present in the country, —they having always

been planted in favourable localities, and near the residence of the

proprietors.

From what I have said above, it will appear evident, that the disease in

the larch is attributable to the want of proper drainage of the soil.

Since I came to Arniston, to act as forester, I have recovered a

considerable extent of young larch plantations, which were fast going

back, and that simply by draining the soil, in order to draw away from

^it superfluous water, as well as to cleanse it from bad qualities which

were natural to the soil, and formerly prevented the healthy development

of the larch tree. These young larch plantations were under fifteen

years of age when I drained them; but I cannot say if draining would

recover plantations of an older standing. In all cases where it is

desirable to cultivate sound larch timber, the land should be drained

with open cuts at eighteen feet distance, and not shallower at first

than eighteen inches deep; and as the plantation advances in age, the

drains should be gradually deepened, and kept properly clean, and

stagnant water never allowed to remain in them: for however well land

may be drained at first, if those drains are not kept in a clean running

state, in order to prevent stagnant water lodging in them, they will

ultimately be of very little benefit to the rearing of healthy larch

timber.

SECTION III. HOW TO

FIND THE VALUE OF GROWING PLANTATIONS, AND OF FULL-GROWN TIMBER TREES.

The valuing of

plantations is a point in forestry which, to be done properly and

justly, requires the exercise of the judgment of a man who has had long

practical experience in the matter. He who gives himself out as a

valuator of plantations, in the settlements and divisions of landed

property, must be possessed of an accurate knowledge of the prospective

value of all the plantations that can possibly come under his notice,

under the age of full-grown timber. He must have an intimate knowledge

of the habits of growth of the different species of forest-trees, and of

the influence of soil and local climate on their periodical increase of

timber; these properties being absolutely necessary in the valuing of

young plantations, while they are under the age of full-grown timber

trees: and seeing that such properties are only attainable by a pretty

long course of experience as a practical forester, I shall here state

only the general method of going to work in valuing plantations.

In taking the present transferable value of plantations, they are

divided into three different and distinct classes, namely:—

1st, Plantations not thinned for the first time.

2d, Ditto, which have been thinned, hut are under full-timber size.

3d, Ditto, full-timber size.

As each of these classes of plantations is valued in a manner different

from the others, I shall here treat the manner of valuing in each case

separately. With regard to the first, then—were I called upon to give

the transferable value of any young plantation which had not been

thinned for the first time when I saw it, I would in the first place

calculate the original expense of fencing and planting; and having

ascertained this point, I would next measure the extent of the

plantation in acres, and put upon it a rent per acre, corresponding with

the land in the immediate neighbourhood, but in all cases making an

allowance for inaccessible heights and hollows. Then, the rule for

finding the valuation is—to the cost of fencing and planting, and the

rent of the land occupied for the time, add the sum of compound interest

on the amount of these, and the result will be a fair transferable value

between two parties.

With regard to the second class of plantations mentioned above, namely,

those which have been thinned, but are under full-timber size:—

When trees attain a size when it is necessary to thin them for the first

time, they will then afford certain evidences on which to found

calculations of their ultimate produce and value. Therefore, at the time

when young trees show evidence of their future health, and until they

have attained to a full-timber size, the valuation of all plantations of

such trees ought to proceed on the principle of prospective value, and

the rule for doing so is this :—first, Determine the number of years the

trees will require to arrive at maturity; second, calculate the value of

all thinnings that are likely to be taken from the plantation before it

arrives at maturity, and that in periodical thinnings of five years from

the time that the valuation is taken; and third, estimate the value of

all the trees which will arrive at perfection of growth ; and from the

total amount of these sums, deduct compound interest for the period the

trees require to attain maturity, and the result will be the present

transferable value of the plantation.

With regard to the third class of plantations as above stated—namely,

those which have arrived at full-timber size:—

As this is a class of plantations which every forester ought to be able

to value at sight, I shall be more particular in pointing out the method

of going to work in the valuation of such. Few foresters are ever called

upon to value the two first-named classes of plantations, but the case

is altogether different with regard to full-grown trees: these are the

harvest of their labours, and they are almost every day called upon to

cut down and value trees of full-grown dimensions. In this case it is

not the transferable value of the unripe crop as found upon the land

that we have to do with: it is the simple value of wood itself, the

value of each tree in its perfect state, in so far as the ground is

qualified to produce it. It is often necessary that full-grown timber

trees should be valued previous to their being cut down; and

particularly in the case of a transfer of property, it is absolutely

necessary to have this done, seeing that the trees are a part of the

property to be sold. In taking the value of timber in its growing state,

two methods are in practice among wood-valuators: the one is to measure

the height of each tree by means of a measuring pole with a ladder, and

by actually girthing the tree in the middle with a cord, and finding the

contents in the usual manner of measuring round timber: the other method

is, that of judging by the eye the number of feet that each tree may

contain.

"With regard to the first method—namely, that of measuring the trees by

means of a pole with a ladder;—some suppose that this is the most

correct way of going to work in the valuation of growing timber; and in

consequence of this opinion having for some time past prevailed among

the older class of valuators, much precious time has been lost by them,

as well as useless expense entailed upon the proprietors who have

employed them. I have myself seen three men, apparently busily employed

for the space of ten days, in the measurement of four hundred trees, by

the method in question; and even after all their labour, their valuation

was disputed. A friend of mine being called in to make a second

valuation, he did so by estimating the size of each tree by sight, and

did the whole work in about half a day; and when those trees actually

were cut down and measured, his report of the valuation corresponded to

within five per cent of the truth, while the report given by the other

party was thirty per cent beyond the truth;—this instance at once

pointing out the possibility of being very incorrect in the valuation of

trees measured with a pole and cord. From the many obstacles that are

apt to come in the way, it is almost impossible to measure correctly any

large tree in its growing state; and by a short sketch of the manner of

proceeding in this kind of work, the impossibility of correctness will

at once appear. In measuring trees in their growing state, the valuator

has with him two men— the one carrying with him a pretty long ladder, in

order to get upon the trees from the ground; while the other bears with

him a measuring pole, generally about ten feet in length, divided into

feet and inches for the sake of measuring the length of the trees, and a

tape line marked with feet and inches for the purpose of taking the

girth of the tree in the middle. With these assistants thus furnished,

the valuator proceeds by causing the man with the ladder to hold it to a

tree, while the other goes upon it, and with his rod measures the height

of the tree as he proceeds upwards. Having ascertained the entire

height, as far as may be considered measurable timber, he again measures

downwards, one half of the height of the tree, in order to take the

girth at that part, for the calculating of the side of the square; and

in this manner the valuator proceeds from one tree to another, noting

down the dimensions as he proceeds. Now, as to correctness, this method

would do very well, provided that there were no branches upon the trees;

and, no doubt, the operators always choose that side of a tree which is

most free from branches; but notwithstanding, there are few trees which,

in taking a straight line from top to bottom, have not several branches

to intercept the object. And this is what makes their measurement so

very incdrrect; for when the man with the pole has his line of

measurement intercepted by one or two branches, he generally has to

change his position upon the tree, and this often many times in the

ascent of one tree;—often causing consequently a defect of several feet

in the value of one tree, either less or more. Mr Monteith, the

well-known author of the Forester's Guide, invented an instrument which

wrought with a wheel, in taking the height of a tree, and with this

instrument he himself practised, in the valuation of forest trees. But

for the same reason that I have already mentioned,—that is, from the

wheel being interrupted by the branches of the trees,—it soon fell into

disrepute, and is now scarcely or ever used: besides, the time and

labour necessarily required for accomplishing the work of valuation by

the method above referred to, is very much against 2ts being used by

active valuators of the present day. Such men, in almost all eases,

accustom themselves to value any standing tree simply by sight— which

is, indeed, when done by an experienced man, the method most to be

depended upon. The eye is not easily deceived in the comparative

magnitude of any two or more objects; and more particularly, if the

action of the eye be long accustomed to compare the relative sizes of

different objects of the same form, its judgment, if I may so speak,

becomes almost indisputable: at least, a man is very seldom deceived by

his eyes in the viewing of an object, if he have but accustomed them to

act in accordance with his judgment; and this is all that is required in

order to give a correct idea of the size of any tree. It merely requires

that the eye should he accustomed to the work, and never to pass

judgment on the size of a tree, until the mind be actually satisfied of

the truth of the impression produced.

Every forester ought at once to be able to estimate the size of any tree

upon first sight of it. But a course of training is necessary before

being able to do this; and as I myself, in all cases of valuing growing

timber, pass judgment of the size simply by sight, I shall here point

out the course of training necessary to those who may wish to become

active in this most useful point in forestry.

Those who never have accustomed their eyes to compare the relative sizes

of different objects, may at first be led to think that it is impossible

for any man to give a correct judgment of the exact bulk of one tree as

compared with another. This opinion, at first sight, is natural; but the

power of habit is well known to be incredible; and to those who may

entertain the idea of there being great difficulty to overcome, I beg to

say, that a few weeks of persevering practice will overcome all the

difficulty. When I first commenced to train myself to value trees by

sight, I was engaged in the thinning of plantations from twenty to forty

years old. For a few weeks, I, in every case of cutting down a tree,

first eyed it from bottom to top, and from top to bottom, and passed my

judgment as to the number of cubic feet it contained, before I cut it

down: and as soon as I had the tree cut down and pruned, I measured the

length with my rule, and took the girth in the middle, and upon casting

up the contents, I compared the truth with my previous judgment of the

matter: and at the end of three weeks, which time I was employed in the

thinning of the plantations mentioned, I could have told, to within a

mere trifle, the actual number of feet and inches in any individual

tree, before I cut it down. And in like manner, I practised myself when

cutting down large trees, embracing every opportunity of improving my

judgment upon the point, until I came to have perfect confidence as to

the correctness of my decision.

But there is one remark which may be useful for me to mention in this

place, relative to the correctness or incorrectness of the judgment of

the eye in taking the size of a tree—and that is, the mind must be

perfectly at ease. A valuator, with his mind uneasy upon any point

foreign from his present purpose, is certain to commit errors; and this

I mention, in order that any young beginner who may read this, and may

commence his learning in the way I did, may be upon his guard at all

times when valuing.

Having thus pointed out the way by which any forester may acquire the

useful habit of valuing trees by sight, I shall now give a statement of

the manner in which I generally go to work in the actual valuation of

the trees in a plantation.

When called upon to take the valuation of a plantation of full-grown

trees, or, as it may be, a thinning of trees from a plantation, I

provide myself with a pretty large pass-book, containing, as usual,

money columns on the right-hand side of each page, and the spaces upon

the left-hand side of the money columns I divide into four equal parts,

parallel with them; the first space upon the left-hand side is for

entering the numbers to correspond with these as intended to be marked

upon the trees; the second for entering the species of each tree as it

is numbered ; the third for entering the number of cubic feet contained

,in the tree as marked; and the fourth contains the price, per cubic

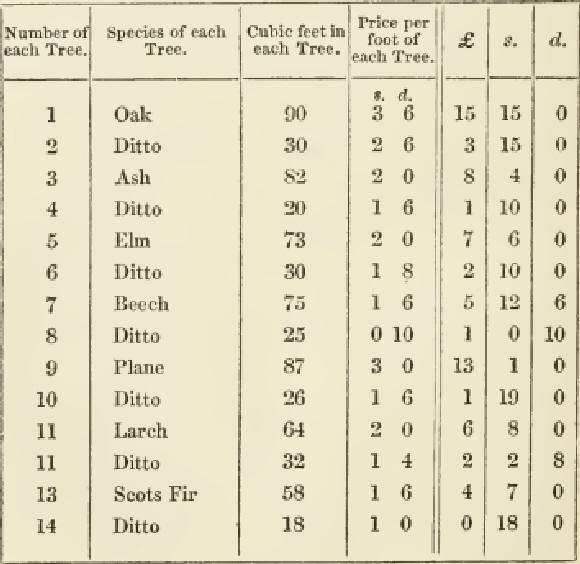

foot, of each tree as numbered. The following sketch of this form of

book will more readily assist the learner :—

In the act of valuing

trees in the forest, I do not, of course, take time to sum up the value

of each tree, but leave the money-columns blank until I have the work

finished, or at least until the evenings when I get home, and then I

have leisure to do so correctly. Having provided myself with a book of

the description mentioned above, all ready and ruled, with the numbers

filled in, and the uses of the columns written along the top of each

page, I next engage three, or perhaps, if the trees are hard in the bark

and difficult to mark, four men of active habit, each provided with an

iron adapted for the marking of figures upon the bark of trees : one of

the men I cause to begin by marking No. 1 upon the first tree to be

valued, a second man marks No. 2, a third No. 3, and the fourth No. 4;

and in tliis manner the four men follow one another, each of them

marking his own number next in succession upon another new tree : that

is, if the first man mark No. 1, his next in succession will be No. 5,

if the second mark No. 2 his next in succession will be No. 6, and so on

with the rest. When the men are properly arranged at their work of

marking the trees, I next commence myself with the tree having the mark

No. 1 upon it, and write opposite the same number in my book the species

of the tree, next the number of cubic feet that I think it contains, and

lastly, the price per cubic foot of each tree, as I think it would

really bring in the market at the time of valuation—and in the same

manner I go on with each and every tree that is to be taken value of.

I may remark here, that every valuator of growing timber, previous to

entering upon the valuation of it in any locality with which he is not

well acquainted, should in all cases make himself properly aware of the

general prices of wood in that district; for if he do not, he will

unquestionably commit gross errors in his work. If, for instance, a

valuator were to be called from Edinburgh to value wood in the county of

Peebles, or any other inland district, and he proceeded to value the

same according to the rate of wood-sales in the neighbourhood of

Edinburgh, his valuation would, of course, be about one-half too high;

because, in the county of Peebles, or indeed any other inland district,

there is little or no demand for wood: consequently, before the wood

could be sold, it would require to be carted by the purchaser a great

distance to reach a market; and seeing this, the valuator should always

regulate his prices per foot according to the prices that he knows will

be given at the nearest seaport, deducting the expenses which will be

necessary to carry the timber between the place where it is growing and

the seaport where it is to be sold.

SECTION IV. A FEW

PRACTICAL HINTS RELATIVE TO THE MANNER IN WHICH TREES OUGHT TO BE

PREPARED FOR SALE.

In order to the disposing

of wood growing upon gentlemen’s estates to the best possible advantage,

a few practical hints may not be out of place here.

All sorts of hard-wood, the bark of which is not used for tanning

purposes, should be cut down for sale from October till March ; during

those months the sap of the trees is in a dormant state, and when wood

is cut in such a state it is of better quality for any permanent use

than when cut in the summer months.

All oak, larch, and birch, the bark of which is used for tanning

purposes, should be cut down and peeled just when the buds of the trees

are expanding into a green state; but in all cases where the wood of

these trees is wanted for permanent use, the trees should be cut from

October till March.

All sales of wood should be conducted upon the principle of public roup.

At public sales there is always a competition of purchasers, who

generally set up the wood to its proper value.

Where there is a saw-mill upon a gentleman’s estate, for the cutting up

of trees for valuable purposes, and where there is a good demand for

wood, private sales of wood after being cut at it generally pay the

proprietor better than when the wood is sold in its rough state and

without measurement.

In preparing wood for a public sale, each sort should be arranged into

separate lots by itself, and no individual lot should contain less

timber than twenty-five cubic feet, in order that there may be a

cart-load for the purchaser.

All timber of good quality should be lotted separately from that of

indifferent quality. Let good timber be sold in lots by itself, and bad

timber in the same manner; and if possible, whatever number of trees may

be put into a lot, let them be nearly of an equal size.

All oak timber should be sold in its growing state, unless the

proprietor wish to have the cutting and peeling of it kept in his own

hand, which is advisable, seeing this sort of work is more likely to be

done to the general advantage of the stock than when done by strangers.

At all events, in all cases of taking down oak trees, the cutting, at

least, ought to be done by the proprietor’s men, not only with a view to

the safety of the stools, but also for the sake of other trees that may

not be intended to come down. In the case of thinning out among large

full-grown oak trees, I have seen much damage done to the standards from

carelessness in allowing the fallen trees to smash the branches of those

which were to remain; and in that instance the purchaser cut down the

trees himself, and, not being a conscientious man, he had no respect to

the remaining trees. Now, in all cases of like nature, were the work

done by the proprietor’s men, it would be done with care.

All trees for sale should be cut down with the saw, when of a size above

six inches diameter at the bottom; and all trees under that size may

very properly be cut with the axe. In cutting a large tree with the axe

much valuable wood is lost at the bottom part; but when cut with the

saw, all the available wood may be preserved.

When trees are laid together, in the way of letting out for sale, the

bottoms and tops should all be laid one way, and that in a regular

manner.

The lots, as they are prepared for a sale, should be all numbered, and

entered to a corresponding number in a book kept for the purpose; at the

same time stating the kind of wood that each lot consists of, with the

number of trees in it, and the value of the same. When this necessary

precaution is used, should any dispute take place relative to the lots

afterwards, such may be at once adjusted by referring to the roup roll.

All lots of wood prepared for public sale should be carried out of the

plantations, and put upon road-sides for the conveniency of purchasers

getting to them with their carts.

THE END. |