|

MANNER OF PROCEEDING WITH

PLANTING OPERATIONS. EXPENSES OF LAYING DOWN LAND UNDER NEW PLANTATIONS.

THE KEEPING OF TREES IN A YOUNG PLANTATION CLEAR FROM GRASS AND WEEDS.

THE NATURE AND NECESSITY OF THINNING PLANTATIONS. THE NATURE AND

PRACTICE OF PRUNING PLANTATIONS.

SECTION I. MANNER OF PROCEEDING WITH PLANTING OPERATIONS.

In all planting of young

forest trees, the superintendent of such operations should be a man who

has had considerable practical experience in that line of work. No man

should undertake, or be allowed to undertake, the management of planting

operations, who has not had at least ten years’ experience in his

profession; unless he has had such experience, and that rather upon an

extensive scale, he will not be able to judge for himself in any

extraordinary contingency. A man who is allowed to undertake planting

operations without proper practical experience, is generally put off his

way by every change of the weather, and then knows not how to proceed;

in such extremities he seeks the advice of others, who, very likely, are

as ignorant in the matter as he is himself: consequently, the mind of an

inexperienced man is liable to give in to wrong advice, and then the

whole work goes wrong; time is lost, the work is badly done, and, in the

end, failure is the sure result. This state of things, I am aware, often

happens in planting operations; therefore, for the guidance of those who

may not have experience enough, I shall here lay down, in a general

manner, the way of proceeding with planting operations as they ought to

be done.

The land having been all well drained, when it is intended to plant

young forest trees, and the drains having been allowed to act upon the

ground for at least one month previous to commencing to plant, and also

the greater part of the pits made for any hard wood that may be to

plant,—the next important point that the planter has to attend to is the

bringing forward the young trees from the nursery. The superintendent of

the planting operations, previous to the arrival of the trees upon the

ground, must walk carefully over the whole of the land to be planted,

and note down in his memorandum book the number of the different sorts

of trees that will be required for the planting of each division, as it

naturally divides itself according to soil and situation; and having

noted this in his book as correctly as he possibly can, he will, upon

the arrival of the cart with the young trees, cause to be sheughed in a

careful manner, in

Laid in quantities in

furrows, to prevent their withering.

each district, the number and kinds of trees required for it.

The number and kinds of

trees having been laid down in their respective places, the

superintendent of operations will next bring forward the number of men

that may be thought requisite for the work to be done; and each man or

planter ought to provide himself with a boy for the purpose of handing

the young trees, and each boy should be provided with an apron for

holding his trees when taken out of the ground, as well as to keep their

roots safe against any cutting winds that may prevail. These matters

being all properly arranged, the superintendent will, when his men are

all collecting in the morning, strive to be the first man upon the

ground, and arrange in his own mind quietly as to what sort of a day it

is likely to be; and if it have the appearance of being a fine one, put

the men to plant upon the most exposed parts of the ground, and if

otherwise, upon the most sheltered parts. Although the day should prove

wet, if the men have all collected, and are willing to work, let them do

so, but only as long as the ground is not saturated with rain, which can

at once be known when the young trees will not firm in the ground; as

soon as the superintendent sees that the men cannot, with the usual

beating, firm the trees in the ground, let him give orders to drop work

at once; to persevere in such a state of tilings is the worst of

management. However, upon dry ground, this will seldom occur. If the day

should prove frosty, let the men be set to make pits in a dry part of

the ground—an operation which should always be left for days of this

nature; but the superintendent should be most careful never to allow a

tree to be planted in such pits till the frost has been properly thawed

out of the earth; to plant a young tree among frozen earth will kill it

as certainly as if it had been put into boiling water: therefore the"

planter should always be extremely careful to avoid this.

In planting a piece of ground, if there be hard wood to put into it,

those should be all planted first; that is to say, previous to planting

firs among them. In order to save time, I very often cause a few men to

go on filling up the pits that have been made with hard wood, in the

proportions that may be thought necessary as to the number of each sort;

and immediately behind these I cause perhaps twice the number of men

employed in planting the hard wood to follow them with the firs, filling

up the ground to the requisite closeness as they proceed.

The superintendent must go backward and forward among the planters,

minutely examining their work; in short, he must examine almost each

tree as it is put into the ground, whether it may be done by the pitting

or notching system, and see that it is properly planted and made firm in

the ground; and when the least fault is observable, it ought to be

checked at once, and the fault laid to the person who did it. Every cut

made with the spade in the act of planting a tree should be firmly

closed, in order to prevent the drought from taking effect upon the

roots.

The principal use of the boys in the operation of planting is to put the

plant into the pit, and to hold it there until the men have it properly

fixed in its place; the boy should never be trusted with making firm the

plants, as is too often done by careless planters, but the man should be

made responsible for the good planting of the trees. In planting by the

notching system, the boy puts the roots of the young tree into the cut

as it is opened by the man with his spade; and in this case also the man

must attend to make the trees firm in their place. Many planters throw

down a tree to each pit, and that for a considerable distance in advance

of the men at work, which is decidedly a bad way of going to work, for

by this method the roots of the young trees are often exposed for half

an hour and more to the open air, which is always against their welfare;

whereas, when boys are employed for the purpose, they keep the roots of

the plants sheltered in their aprons from the drying winds, and, at the

same time, the man has always more opportunity for the handling of his

spade properly than if he had to stoop down and lift a tree each time he

came to a new pit, which he must do where no boys are employed.

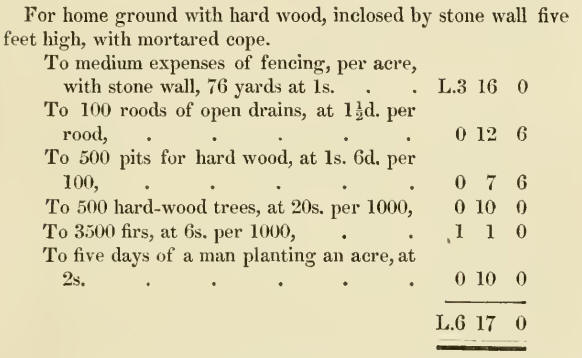

SECTION II.—EXPENSES OF

LAYING DOWN GROUND UNDER PLANTATIONS

In calculating the

expenses likely to be incurred in the laying down of a piece of land

under a crop of young forest trees, the proprietor has to consider,

first, the nature of the figure in which he may intend to lay out his

plantation. Upon the form or figure of a plantation much of the expense

of fencing it depends; and as this item forms a very considerable

proportion of the entire cost, it will be proper here to show the

circumstances which, when attended to, lessen this expense.

When a proprietor intends to plant a piece of land upon his estate, say

to the extent of fifty acres, he cannot exactly calculate the sum that

would be required for the fencing of it until he has laid out the line

of plantation, and actually measured the same—unless, indeed, he shall

fix upon a regular-sided figure; and in order to illustrate the truth of

this, I shall here give an example : —To lay out a plantation of fifty

acres in extent, in the form of strips of four chains, or 88 yards

broad, the proprietor would require to erect 5676 lineal yards of fence

to inclose it; and supposing the fence used in the inclosing of this

plantation in the form of strips to be stone dyke costing Is. per yard,

then the whole expenses of fencing, in this instance, would amount to

L.283, 16s., equal to L.5, 13s. 6d. per imperial acre upon the land

inclosed.

Again, supposing that instead of laying out the fifty acres in the form

of strips, the proprietor wished to lay out the same quantity of land in

the form of a regular square ; then the side of a square that would

contain fifty acres will be 490 yards; consequently, the four sides

added together will amount to 1960 lineal yards, which would be the

extent of fencing required, instead of 5676, which was required in the

last instance, although the same quantity of ground is inclosed in both

cases. And taking again the 1960 yards to be stone dyke at Is. per yard,

the whole expense of fencing the square of fifty acres would be only

L.98, equal to L.l, 18s. 6d. upon each acre of the land inclosed. Now

this at once points out to proprietors of land the great utility of

planting all plantations in a solid compact form in order to prevent a

large original outlay; by the cheaper method a much more valuable

plantation is raised, independent of any other consideration.

The above examples point out the impossibility of giving any thing like

a just rule whereby the expenses of fencing ground for a new plantation

can be ascertained, which in all cases must be influenced by the form in

which the ground is laid out: however, in calculating the probable

expenses necessary to be incurred in the laying out of plantations per

acre, I shall give two examples, as under:—

The first example

contains the highest cost per acre that ever I found necessary for

planting of hard-wood plantations, —and the second contains the lowest

that ever I could get the work done properly for. I am aware that many

planters say that they can do the work more cheaply—but this of course

must depend upon the average amount of wages as given to labourers in

the district; what I have stated above is taken from notes of expense

actually incurred by myself; and, of course, I can speak with certainty

upon the subject only so far as my own experience goes.

SECTION III. THE

KEEPING OF TREES IN A YOUNG PLANTATION CLEAR FROM GRASS AND WEEDS.

Any piece of ground

having been planted with young forest trees, in order to keep them in a

healthy growing state, it is necessary to have them kept clear of all

long grass, as well as any other weeds that might have a tendency to

injure them, by over-topping and crushing them down. Upon this head, the

forester should keep a sharp lookout during the summer season,

particularly the first one after the young trees have been planted; and

wherever it is observed that the grass or any other weeds are likely to

become strong, and to fall down upon the young trees, a careful man,

with a few women and boys under his superintendence, should be sent over

the different young plantations, who, with common shearing sickles,

should be made to switch away all grass, &c., from every young tree that

may require this to be done.

This work must be carefully done, particularly where boys or other young

people are employed, as they are very apt to cut off the tops of many of

the young trees if they are not strictly looked after; therefore, the

man who is put over them should not work alongside with them, but go

immediately behind them, and closely inspect all that they have done as

the work proceeds, observing that they do not pass over any young trees

requiring to be cleared, as well as seeing that those cleared be done in

a proper manner. This operation ought to be performed twice during the

summer season, viz.—between the middle and end of the month of June, and

a second time in the month of August; and where the trees are growing

among vegetation of a rank description, the same work may require to be

repeated for three or four years successively, or at least until such

time as the young trees rise above the rank growth of the weeds in the

summer season.

Young trees, besides being apt to be injured by grass and other common

weeds, are often still more seriously hurt by whins and broom growing

among them. It very often happens, that young trees are planted where

whins and broom have been cut down, and not grubbed out by the roots; in

which case, the whins in particular are sure to push out a stronger and

more vigorous growth than ever the following year. Whenever this may

have been the case, the planter ought to have particular attention paid

to sueh parts, and see that the young growths of the whins as they rise

up do not hurt the young trees. And for the purpose of elearing away the

young shoots of the whins, a strong siekle will be found to answer the

purpose well; and in the doing of the work, they ought to be shorn clean

by the surfaee of the ground, where-ever they are found among the young

trees, whether they may he injuring them in the mean time or not: for

though the whins may not hurt the young trees in many places in a young

plantation for the first year of their growth, they will decidedly do so

the second year, when it will he much more difficult to get the better

of them. Therefore it is always necessary to cut such rubbish during the

first year of their growth, when in a soft state; besides, if they are

allowed to stand undisturbed upon the ground for a whole year, they give

shelter to rabbits, hares, and other vermin, which are always a most

dangerous stock in young plantations.

Where whins have been, even although they may have been grubbed by the

roots previous to the ground being planted with trees, it is, I am

aware, a most difficult matter to take them out so clean as to prevent

any roots that may be left in the ground sending up shoots of

considerable strength the first summer after; consequently, it is

necessary to attend in a particular manner to those young plantations

where whins have existed previous to the young trees being planted. I

have frequently seen large tracts of young plantations entirely ruined

from not having been cleared from rubbish in due time; and in such a

case, where this necessary clearing of the young trees has been

neglected, a replanting of the ground must take place before any thing

good can be expected. This of course is the cause of a great outlay of

money, all which might have been saved had due attention been paid at

first.

The necessary expense of doing this sort of work is but trifling. Upon

the estate of Arniston, we employ a man with six young people, from the

beginning of June to the end of August, constantly clearing among the

young plantations; and I find that where no whins are, the expenses of

keeping clear a young plantation, for the first four years, costs about

16s. per acre; and where there are whins to contend with, the operation

costs about 25s. per acre, until the trees rise above them.

SECTION IV. THE NATURE

AND NECESSITY OF THINNING PLANTATtONS.

Thinning is one of the

most indispensable operations in arboriculture. The right understanding

of the nature and design of thinning plantations forms one of the most

important points to be aimed at by every practical forester.

The object which ought to be aimed at by the forester in the act of

thinning, is the regulating of the trees in a plantation to such a

distance one from another, and that in such a manner as is, from well

observed facts, known to be favourable to the health of each tree

individually, as well as to the general welfare of the whole as a

plantation.

In order to grow any plant to that size which the species to which it

belongs is known to attain under favourable circumstances, it is

necessary that it have space of ground and air for the spread of its

roots and branches, proportionate to its size at any given stage of its

growth; and upon this the whole nature and intention of thinning

plantations rest.

It is, in my opinion, much to he regretted that there does not exist,

both among proprietors and foresters, a sounder knowledge relative to

the nature and intention of thinning plantations than there is. I have

frequently seen plantations upon a high situation going back, from

having been injudiciously thinned; and in a low situation, I have as

often seen them going back from not having been thinned at all: where

the blame rested I know not, neither is it my business to inquire into

that, but this I must say, that in all such eases there is evidently bad

management.

There are, indeed, few proprietors’ estates in Scotland upon which there

is not considerable room for improvements, as regards the thinning of

their plantations. There is a decided loss of timber, as well as

shelter, whenever plantations are made too thin; and there is also

equally as decided a loss where they are not sufficiently thinned.

Wherever plantations have remained long in a close state, and are

thinned suddenly and severely, which I term injudicious thinning, they

are at once cooled; and that I reckon equal to being removed a few

degrees of latitude farther north, or to a situation a few hundred feet

higher than the original; and the natural consequence is, that the

greater part of the trees which have undergone such treatment, become

what is generally termed hide-bound—the bark contracts, and prevents the

free flow of the sap, consequently it stagnates and breaks out into

sores; the trees fail to make wood; and, in fact, the whole plantation

falls into a state of consumption and declines gradually. I have

frequently been called upon to examine and give my advice relative to

what ought to be done with plantations in such a state as that described

above; and wherever I have found plantations above thirty years old to

be in the state described, and to have stood in the same state for four

or five years, without showing much signs of any improvement, I have

always in such cases recommended to cut down at once, drain, and replant

the ground. However, I may here mention, that if the situation be a

rather sheltered one, and the soil dry, a recovery of an over-thinned

plantation will often take place, although the trees, after having been

checked, will never attain that size they would have done had they been

otherwise treated ; but where the situation is exposed, and the natural

soil cold and damp, recovery is out of the question.

Upon the other hand, where plantations are not enough thinned, the trees

become drawn up weakly, and seldom attain the size of useful timber

before maturity comes upon them. And where any plantation has stood long

in a state without being thinned, particularly a fir plantation, it is,

I may say, impossible to recover it; for if even a very few trees be

thinned out, a number of others, from the want of their shelter, are

sure to die, which ultimately causes blanks to occur here and there, and

the wind getting play in such blanks, great havoc is often done among

the trees during a storm. As an instance of this, I may here mention,

that upon the estate of Arniston, a fir plantation of above thirty

years’ standing, and to the extent of nearly forty acres, had been

allowed to grow on in its natural state from the time that it was

planted up to the period stated, when an attempt was made to take a few

trees out of it, by way of thinning it gradually; and this having been

done, many more were blown down the very first storm that occurred, and

an opening having-been made by the wind, the whole plantation in a short

time became a complete wreck, so much so, that when I came to the place,

I had the whole cleared off and replanted.

From what has here been stated, it will appear evident that there is a

great loss sustained by every proprietor who allows his plantations to

be mismanaged, either from not thinning them, or from over-thinning

them; and the result may be reckoned the same in both cases.

Upon many estates, I have often regretted to see plantations of

considerable extent, and of perhaps forty years’ standing, with the firs

all overtopping and crushing down the hard-wood trees. From the

appearance of such plantations, it was evident to me, that they never

had been thinned: the hard-wood trees were miserable-looking things, and

not more than ten or twelve feet high, striving for existence; while the

firs, which, of course, grew more rapidly, were more than thirty feet

high, and of a broad spreading habit, from having been widely planted

among the hard wood: and in this state many plantations have been

allowed to grow up, under the false impression that the firs were of

more value than the hard wood for the sake of shelter.

Now, I beg to ask if any circumstance could be a more convincing proof

of the want of sound knowledge relative to thinning? If the hard-wood

trees had been relieved in due time, would they not at forty years’

standing have been valuable, both as timber and as affording shelter?

Could not the firs have been all taken out for estate purposes, and been

of value to the proprietor, while at the same time they left a more

valuable crop of hard wood on the ground? But as the case was, the

hard-wood plants were useless, and past recovery; and upon the ground

where a valuable crop of hard wood might have been, there existed only a

few firs of little permanent value, either for shelter or as timber.

The distance at which trees in a plantation ought to stand one from

another, must in all eases be determined by the nature of the soil and

situation upon which the trees grow, and also upon the ultimate object

the proprietor may have in view as regards any particular plantation;

but as a sort of guiding rule for thinning, I may here state, that if in

any particular plantation it should be intended to rear up trees for

park or lawn scenery, then, in such a ease, the distance between each

individual tree ought to be at least equal to the height of the same;

and this rule ought to be kept in view at all stages of the growth of

the trees, in order that they may have free room and air to form

spreading tops as well as massive trunks, which is the true and natural

form of every tree, and which constitutes the great beauty of lawn

trees.

If it should be intended to rear up a plantation of hard-wood trees

principally for the sake of value in timber, and of giving shelter at

the same time, then, in such a case, the distance between each

individual tree ought to be equal to about one half the height of the

same; and this ought to be kept in view at all stages of the growth of

the trees, in order that they may not have so much free air and room as

to allow of the spread of their branches horizontally, nor yet to be so

much confined as to be drawn up weakly from the want of air. If it

should be intended to rear up a plantation of firs or pines, for the

sake of shelter and timber, then, in such a case, the distance between

each tree ought to be a little more than the third of the height, which

is the distance found most favourable to the useful development of the

fir and pine tribes, as timber trees.

In order to give a clear and practical description of the manner of

proceeding with thinning operations in the forest, it will be necessary

to treat of them under three distinct heads; and which I shall do in the

proper place—(see under the heads, System of thinning mixed hard-wood,

fir, and oak plantations); but it may be necessary here to observe, that

all plantations, ere they require to be thinned, must have grown for at

least eight years, and even this period may in the most of instances be

far too early; in fact, no particular period can be specified as to the

length of time that a plantation should stand, previous to commencing to

thin it; for in this case, much depends upon the nature of the soil and

situation, upon whether or not a plantation may have been well laid out,

and upon the state of the ground, as being dry or damp. These things

considered, it will appear evident, that no particular time can be

stated as to when a plantation should be thinned for the first time; but

that this must be judged entirely by the state of the trees, whether

they may have grown rapidly or not. I have myself found it necessary to

thin a young plantation of seven years’ standing, at which age the trees

were twelve feet high; but upon the other hand, I have much oftener seen

plantations of fifteen years’ standing, scarcely the length of requiring

to be thinned: therefore, observation upon the spot is the only sure way

of determining this point.

SECTION V. THE NATURE

AND PRACTICE OF PRUNING TREES.

For three or tour years

past, many conflicting opinions relative to the pruning of forest trees

have been issued in some of the periodicals of the day ; which opinions,

I believe, have had more a tendency to darken the point referred to,

than to throw light on it. Many have recommended pruning as an operation

eminently favourable to the health of forest trees; many more doubt

this; and as many more affirm that pruning ought not to be practised at

all: and each, as he advocates his own peculiar system of management as

regards this, gives an instance of some plantation he has had under his

care, as undeniably illustrating the advantages of the system he

recommends. Now, all the diversity of opinion arises from the want of a

properly extended knowledge upon the subject in question. A man of

extensive experience comes to find, that no particular rule can be laid

down to answer the pruning of trees in all cases—he finds out that

pruning in some cases is proper, and in others improper; but the

inexperienced man, who wishes to be instructed in the art of pruning,

when he sees one man strongly recommend pruning in all cases, and

another as strongly urge its not being practised in any, is brought to a

stand. He becomes bewildered, and knows not how to proceed; he is not

able in his own mind, from deficiency of experience, to reason whether

in his own case he should prune or not. Now, the only way reasonably to

confirm the mind upon this important point is, not to lay any particular

stress upon any particular example that may be given; but to examine the

true nature of the art of pruning, and the tendency it has to improve or

retard the healthy development of trees ill various situations; in

short, in order to a right understanding of the nature of pruning, as

applies to forest trees, attention must be paid to its effects upon

trees under every variety of circumstances. I consider it proper, that

every proprietor of plantations should be able to judge for himself in

the matter of pruning, and to detect proper from improper pruning ; and

to this end, I shall enter minutely into detail under this head, and

give a distinct statement of my reasons for pruning in one case and not

in another. But before entering into detail regarding the practical

operation, it will, I think, be proper first to examine the effects that

the amputation of a branch from a tree has upon its constitution; and

such previous knowledge will prepare the mind for a bettor understanding

of the true nature of pruning, as it is generally practised among

foresters.

A tree, through the agency of its roots, draws liquid nourishment from

the earth in which they are placed, mostly in a state of solution in

water; which liquid nourishment, or what is generally termed the sap of

the tree, ascends the trunk through the longitudinal vessels, or pores

of the wood; from which again, each branch or limb of the tree is

supplied in succession. The body or trunk of a tree forms one bundle of

longitudinal tubes, through which the sap ascends from the roots to the

branches; and from this bundle, each separate branch is supplied by its

own separate line of tubes; or, which is the same thing, each particular

root of a tree has to dj^aw nourishment from the soil to supply its own

particular branch; and the communication between those two points is

maintained by a particular set of vessels in the trunk of the tree. The

watery part of the sap, when it ascends into the leaves, is for the most

part given off by them in the form of perspiration, and the sap which

remains at this point undergoes a change previous to its descent in the

form of proper woody matter, which change is effected by the leaves

inhaling carbonic acid and other gases, which enter into the composition

of the returning sap; and in this manner there is a continual

circulation of the sap in the tree—the roots drawing in and supplying

the whole with moisture; which, when it is raised to the leaves,

undergoes a chemical change, and is returned in the form of proper woody

matter. And now the practical deduction to be drawn from this is, that

every branch growing out of the main body of a tree, is by nature meant

to act as a laboratory, in which woody matter is prepared and returned

for the joint supply of itself and the body of the tree ; and from this

we are bound to conclude, that when we cut a branch from a tree, we take

away from it the means of supplying it with a certain proportion of

woody matter for its enlargement; and this is, indeed, the case with

pruning in all cases of the operations. But under good management in

pruning, this depriving of a tree of its due means of nourishment is

only of a temporary nature; and in one or two years after the operation

has been done, and when the tree operated upon has had its growth

properly directed, the increase of timber is at once remarkable, as

compared with others of the like nature and age which had not been

pruned, or with others which had been unscientifically managed.

When a large branch is cut off immediately from the body or trunk of a

large tree, the usual sap which supplied it in its ascent from the

roots, will be stopped short, and for a time will ooze out at the cut

part; but shortly, the sap as it rises in those vessels of the trunk

which formerly supplied the branch taken off, becomes stagnated, and

causes rot in that part, which can never be the case while the branch

remains to draw up and prepare the sap in its leaves; and this is the

case in all instances of large branches, as they are cut from large

trees. But in the case of a branch being thus cut from a young sapling

in a rapidly growing state, the tree is not injured, but improved; the

sap of the plant being in such a vigorous state, that rot cannot take

place. Now, the practical deduction to be drawn from this is, that the

amputation of a large branch immediately from the body of a large tree,

instead of being favourable to its health and value as timber, has quite

the contrary effect. I say immediately from the body of a tree, because

the cutting off of a part of a branch is by no means injurious to the

health of a tree ; but upon the contrary, when part of a large branch is

cut off, the How of sap to that part is checked, and the body or trunk

of the tree is in proportion enlarged.

During my practice as a forester, I have had extensive opportunity of

observing the nature and quality of full-grown timber, as it has been

effected by different kinds of management in the way of pruning. Having

seen much timber of all ages cut up for different purposes at saw-mills,

I have had occasion invariably to observe a practical truth, that

wherever branches of above four inches in diameter at their base had

been cut from the trunk of the tree, the wood for a considerable way

under that part which had been so pruned was worthless and of a black

colour; and where much cutting of large branches had taken place in one

individual tree, I have always found such a tree to be scarcely fit for

any valuable purpose whatever, when it came to be cut up; and where the

pruning had been done a considerable number of years before the tree was

cut down for use, the wounds upon the surface were not easily

observable, and in fact, such trees often appear sound to outward

appearance; but when the bark is removed, the pruned part is at once

observable, and the vessels leading from it, down to the roots, are

generally found soft and of a black colour.

Upon the other hand, I have always had occasion to observe, as a

practical truth, that in the cutting up of trees which had not had their

large branches cut off close by the trunk, the timber was of good

quality, and sound throughout, excepting where extreme old age had

caused natural decay; and of the truth of this I am perfectly convinced.

Therefore, I hereby beg to advise every proprietor of plantations,

never, as he values their health as timber, to cut clean from the boll

of a tree a branch which is more than four inches in diameter at its

base.

Having now pointed out the effects that the amputation of a branch from

the trunk of a tree has upon its constitution, I next proceed to detail

the method which ought to be practised with pruning operations in all

cases ; and in order to a right understanding of this most important

point in arboriculture, I shall bring under consideration the pruning of

trees, from the time that they are planted out from the nursery, to that

of their full growth in the forest, under every variety of

circumstances, as I have had occasion to observe them.

Many foresters are in the habit of closely pruning all young hard-wood

trees, particularly elms and oaks, when they are newly taken from the

nursery grounds, and preparatory to planting them out into the forest;

which system of close pruning is most injurious to the health of all

young trees when newly lifted from the ground. The system of pruning

which is generally practised by foresters in this case is, to cut off

clean to the main stem, all strong branches, and only leave a few small

twigs near the top of the plant, with the view of drawing up the sap.

The natural consequences of such a cutting off of all the stronger

branches from a young tree are, that, when the sap ascends in the plant

in the spring, it is arrested at the wound where the first or lowest

branch was taken off, and escapes from the cut part by evaporation; and

the sap being thus arrested, there is a natural effort made by the plant

to produce young shoots and leaves at this point, in order to convert

the sap into proper woody matter; consequently, we almost always find a

few young shoots made the first season immediately under the part where

the lower strong branch was taken from the plant, and all the rest of

the young tree above this growth of young shoots dies—the sap not rising

to carry on life above the part where the new shoots spring out; and,

even if the sap should not be all arrested at the point referred to, the

part above it remains in a sickly and unhealthy state; while the young

shoots produced lower down draw all the nourishment to themselves, and

ultimately form a distorted unshapely plant, unless it be carefully

attended to, by giving* some one of the shoots the preference, and,

cutting away all the rest, allow it to become the top.

The proper manner of proceeding with the pruning of forest trees, as

they are newly lifted from the nursery, and preparatory to planting them

out into the forest grounds, is to shorten all the stronger branches

that have the appearance of gaining strength upon the top or leading

shoot of the young tree; and this shortening of the larger branches

ought to be done in such a manner, as to leave only about one third of

their whole length remaining, with, if possible, a few small twigs upon

it, in order the more readily to elaborate the sap as it rises in the

spring; and in this state the young trees may be planted with the

greatest assurance of success. The great advantage of this method of

pruning young trees is, that when the sap rises in them, the first

summer after planting, there being a regular supply of small

proportionable branches along the main stem, leaves are formed, and sap

is drawn up regularly to every part of the tree; consequently, the tree

maintains an equal vigour throughout. Were all the branches left upon

the young trees, the roots, from the effects of removal, would not be

able to maintain the whole with due nourishment; and the consequence

would very likely be, that the plants would die down to the

ground-level, from which part of the trees numerous young shoots would

issue, much in the same manner as they do from the cut part of those

trees which have been over-pruned.

It is now a well-ascertained truth among all practical foresters, that

when a young tree is in a vigorous state of growth, and the wood full of

sap, previous to its having made any hard wood, any branch may be taken

off without doing the least injury to it; therefore, it is just at this

stage of the existence of a tree, that it can with certainty be made to

do well or otherwise, according as it may be attended to, to give the

top the lead in the growth, to check the stronger branches, and to give

the tree that shape it may be intended it should have when it attains

full age.

When young hard-wood trees have been pruned in the manner above

recommended, and after they have been planted and grown in their

permanent situation for the space of five or six years, they will by

that time have got themselves properly established in the ground; which

circumstance is known by their putting forth considerable shoots of

young wood. At this stage of their growth, it will be necessary to go

over them all with the pruning-knife, and cut close to the main stem or

trunk all the parts of the branches that were formerly shortened, and,

at the same time, to take off clean with the knife all other branches

that may have gained strength, or may have the appearance of gaining

strength, upon the top or main shoot; but it should he particularly

observed, that this pruning ought never to be allowed to be done until

the young trees have decidedly established themselves in the ground, and

are in a vigorous healthy state of growth; for, if it be done while the

trees are in a sickly state, no advantage will be gained, but, upon the

contrary, much injury will be done.

I have now given a statement of the manner of proceeding with pruning

operations, in the case of young trees about to be planted out into the

forest; and also the treatment they ought to receive after being five or

six years established in the ground. There may, however, be,—and,

indeed, too often are,—cases where hard-wood trees, while young, have

been entirely neglected; and, seeing this, it will be proper to consider

the treatment that such ought to receive. I shall first suppose that we

have to do with a plantation of young hard-wood trees, which had

received no pruning at all previous to being planted; and we shall

further suppose, that the trees are oaks, and of five or six years’

standing in the forest grounds. Upon examining the state of young

hard-wood trees of the description above mentioned, it will be observed,

that the greater part of them have died down to the part resting upon

the surface of the ground, and that from this part a number of branches

have issued, each contending for the lead in the growth. In such a case

as this, no time should he lost in giving the strongest and most healthy

shoot the preference, and cutting away all the rest, as well as the dead

part of the tree, nearly by the ground, or at least down to the part

from where the young shoots issue; prune up the shoot intended to he

left for the future tree, by taking off all the stronger branches clean

to the boll or stem; and in this manner go over each and every young

tree in the plantation, always choosing the most healthy shoot for the

future tree, and one which appears to have naturally a good balance of

branches, with the leader or top shoot strong in proportion to the rest

of the branches. We shall again suppose a plantation of oaks, of the

same age as the one above alluded to, but the trees in which, instead of

having been planted without any pruning, have been pruned too severely

when lifted from the nursery ground, and previous to being planted. The

treatment in this case must in every respect be the same as in the

former; that is, all the dead wood should be cut away immediately above

the point from which the young shoots issue; and the strongest and most

healthy shoot being fixed upon for the future tree, it must be properly

pruned up, by taking off all the stronger branches, and cutting cleanly

away the rest of the inferior shoots, which formerly contended with it.

But, in a ease of this nature, where the trees had been overpruned

previous to their being planted, there is often more difficulty in

making choice of a good young shoot, than where no pruning had taken

place at all. And this arises from the young shoots springing from the

main stem in a horizontal manner, and that, too, very often a

considerable way up the stem. In a case of this nature, where a proper

leading shoot, rising perpendicularly, cannot be got, the only way, and

the method I always follow myself, is to cut the main stem by the

surface of the ground, and allow a set of new shoots to rise up. The

chance generally is, that, when the tree is thus cut down, all the new

shoots will rise in an upright position, and a choice can be afterwards

made; but wherever a proper leading shoot can be had, let it be chosen,

although it come away rather far up upon the stem. If it rise

perpendicularly, and the plant be in a vigorous healthy state of growth,

it will succeed well. This sort of work should be done in the spring

months, so that the growth may set in immediately after the operation is

performed.

It very often happens that a forester, upon entering a new situation,

finds that the several plantations which are put under his management

have been hitherto much neglected; he finds that, in many cases, pruning

is absolutely necessary, but he is at a stand to know how to proceed. If

he be a man who has not had much experience, lie is very apt to go wrong

in a case of importance. He looks upon the trees before him, ancl he is,

no doubt, aware that pruning is necessary to their health ; but, in

consequence of some particular circumstance connected with the trees

with which he has to deal, he finds much difficulty in making up his

mind as to the manner in which he ought to proceed. If he should be a

man who has had extensive practice, he will look back upon his former

experience, and consider where and when he had to deal with a case

resembling the one that may be before him : if he has, he will review

the manner in which he went to work in it; and, at the same time, he

will consider the consequences that attended such operations, whether

these were beneficial or not; and, in all cases, he will endeavour to

govern his conduct in pruning operations by the result of his past

experience Whatever method of operations he has known to succeed well,

he will put again in practice, according as the nature of the case may

require; and whatever method he has found to have been followed by

injurious effects, he will avoid putting again into practice except in

particular cases, where he is aware it would answer the end desired.

With regard to the pruning of forest trees generally, all would be

simple and well, provided a distinct practical rule were attended to,

both by proprietors and foresters, for the rearing up of plantations at

every stage of their growth; but in practice, the case is almost always

the contrary, tfo distinct practical rules being adhered to among

foresters as a body, one goes to work in one way, and another in a

contrary way, in the same piece of work, and in the manner of doing the

work all depends upon the practical experience of the man. A man of

sound practical experience finds out for himself what ought to be done,

and guides himself in the execution of his work accordingly; but the man

of small experience, unless he has some definite rule laid down to guide

him, will go to work merely under the direction of his own judgment,

whether that may be right or wrong; and if his master, the proprietor,

has not himself a knowledge of how the work ought to be done, matters

will often go very far wrong indeed, even so much so, that often the

greater part of the plantations upon an estate, if not ruined, are made

of very little value indeed. We will very frequently see plantations

upon an estate overpruned, while those upon a neighbouring one are not

pruned at all, which at once points out the bad management that exists

relative to forest operations in general.

In one place where I acted as assistant forester, I had a most

convincing proof of the want of a practical rule among foresters as a

body, relative to pruning, and which told me at once that they have

hitherto acted in such matters more according to their own private

judgment than upon any well-founded scientific rules. When I went to B-

as under forester, I found the head forester an old man, who had reared

up most of the plantations upon the estate; and the situation being in a

high exposed part of the country, he had never either pruned or thinned

much; in fact, in the most of cases, pruning had never been practised at

all, from the idea that the baring of the trees of their branches would

diminish the shelter that the trees were meant to produce. Many of the

plantations consisted principally of a mixture of ash, elm, and

plane-trees ; and from the circumstance of the firs having been cut out

pretty early, the trees were low-set, and spreading in the habit of

their branches, never having been much drawn up, and were about thirty

years old. Shortly after I went to this place, the old forester died,

and a young man was appointed in his place. The proprietor wishing to

have his plantations improved, and having no knowledge of how the work

ought to be done himself, he of course left the whole management of his

plantations to his forester. The new forester set about the pruning and

thinning of some of the plantations at once, and a number of men were

set to accomplish this: I was appointed one of the primers, and my

orders from the forester were, to prune all the trees left standing upon

the ground, and to give every tree a clear stem to one half its entire

height. The trees being generally from twenty-fiye to thirty feet high,

we gave each tree a clear stem of from twelve to fifteen feet from the

ground; and in doing this, we had often to cut off large branches from

the boll as thick as itself, which gave the trees completely the

appearance of having been manufactured artificially; and, having been

very thickly set with branches all along the trunks, when they were

pruned, the entire trunk was a surface of wounds. "With regard to the

tops of the trees, our orders were not to do any thing, excepting where

two or more tops appeared to strive for the preference, in which case we

left only one, cutting away the others. Having left that place shortly

after this operation of pruning had taken place, in five years after I

went to visit it, and that in order to draw for my own private

instruction a lesson of experience, by observing the effect of the

former severe pruning upon the trees; and the consequence was exactly

that which I anticipated in the doing of the work. Upon looking over

those plantations, the ruin of which I had myself assisted in bringing

about, I felt sorrow to think that gentlemen should he imposed upon by

ignorant men. All along the bolls of the trees and about the wounds

which had been made in the cutting off of the large branches, young

shoots had sprung out; the trees were generally now hidebound, from

having been suddenly exposed, and the atmosphere cooled about them—the

trunks had scarcely increased any thing in girth since they were pruned,

and the top branches had made little or no wood. The trees, generally

speaking, were ruined in their health, and all hope of their recovery

was gone: and from this example I had indeed a lesson of experience for

my future guidance, and my reason for stating the circumstance here is,

that it may be a lesson to others also. The question now comes to be,

whose mismanagement had been the cause of ruin in the case alluded to ?

Whether was the blame attributable to the old forester who neglected to

prune and train up the trees as he ought to have done, or to the young

man who succeeded him and pruned the trees without due consideration and

experience? In my opinion they were both to blame; for, had the old

forester pruned and thinned in due time, all would have been well in the

end; and had the young forester been more cautious, and pruned and

thinned gradually, all might have been well also. The practical truth

that I wish to enforce from this instance of mismanagement is, that in

every forester great caution, combined with practical experience and

reflection, necessary before he commences to thin or prune any

plantation. A gardener or farmer, from the temporary nature of the crops

which they raise, although they mismanage any of their crops, all can be

redeemed in the course of another year; but in the case of mismanagement

in a forester, the work of past years is lost, and thirty or forty

years, with a considerable outlay of extra money, may possibly not be

sufficient to redeem what is put wrong.

Having given the above example of mismanagement, in order to point out

the necessity of using caution in entering upon pruning operations, I

shall now proceed to give a few examples of the manner in which I have

gone to -work in similar cases of neglected plantations; and I am

convinced that, wherever plantations have been neglected as to pruning,

if they are under thirty years old, they may, if dealt with as I shall

here point out, be recovered, so far as to make profitable timber trees,

although probably not to that extent of value that might have been

expected had the same trees been properly pruned and trained up in their

young state.

When I came to act as forester upon the estate of Arniston, I found that

many of the hard-wood plantations under thirty years old had never been

pruned at all, and that there was great need for means being used as

quickly as possible, to put such into proper state. In setting about

this part of our forest operations, I determined to begin with the

younger part of the woods, as being most likely to recover quickly, and

to be of the most value ultimately if taken in due time, and to go on

with the pruning of the older districts of plantations as I could find

convenient opportunity. Having laid down this principle, as a rule of

procedure, I commenced first upon a plantation of oaks, about twelve

years of age—which plantation, I saw, had never, up to the period I

commenced upon it, been either thinned or pruned. The first thing I did,

when about to commence pruning in this piece of plantation, was to go

carefully over the whole, and examine most minutely its state;

observing, in a particular manner, whether or not the situation was

exposed; and being convinced, from the general bearing of other

plantations in the neighbourhood, that the situation was rather

sheltered than otherwise, I determined upon thinning-out the firs pretty

freely from among the young oaks: having done so, and had the firs all

cleared off which were out, I found that the young oaks had been a good

deal crushed down by the firs, which had grown very freely as compared

with the oaks; and in consequence of having been thus crushed down, many

of the latter had grown strongly to side branches, and not to height;

but wherever the oaks had had free top room, with firs rather close upon

their sides, they were tall plants and generally well shaped. The

average height of the oaks was from five to eight feet; the bark of the

trees was clean and fleshy, and generally speaking they were in good

health. In the pruning of those trees, I first had all the small

branches not exceeding two-thircls of an inch in diameter at their base,

cut from the trunks, and close to the bark, to the height of about

one-third the height of the tree in each case; next, all branches which

grew upon the same part, with a diameter at base exceeding the last

mentioned, I cut off to within about four inches of the stem or trunk

from which they proceeded, leaving the stems in the mean time; and all

large top branches, which appeared to be gaining strength upon the

leading top shoot, I shortened down to nearly one-half of their whole

length : but in all cases where two top shoots appeared, I cut one of

them closely away, always leaving the one which appeared to be the most

healthy and strong, and which at the same time appeared to come most

directly from the centre of the system of the tree.

But I must observe here, that in the pruning of a young hard-wood

plantation, all the trees do not require to be pruned to the same

extent—in many instances it will be found that pruning is not necessary

at all; and so it was in the case of the plantation I am referring to.

Wherever a hardwood tree is drawn up rather closely among firs, with

sufficient head-room, it seldom produces many side branches, but will

grow upwards to the light; therefore, in all cases of pruning, where the

side branches upon a young tree are few, let such remain, and merely

shorten them down where they are long and slender. Pruning is an

unnatural operation, and ought always to be avoided unless absolutely

necessary ; that is, it ought to be avoided wherever the tree does not

produce unnaturally strong side branches, excepting in so far as to

clear from branches one-third of the height of the tree from the ground,

in order to form a trunk; and even upon this part, where the branches

are large, they ought to be taken off gradually, as already noticed.

Having gone through this plantation, and pruned the trees therein in the

manner above described, I allowed it to remain so for the space of two

years; when I again went through it a second time, and pruned in the

following manner all the oaks that stood in need of it.

Having taken out a few more of the firs, which I observed were rather

encroaching upon the young hard wood, and having examined the general

state of the same, I found that they had thriven remarkably well during

the two years since I pruned them. I now found, that from being relieved

of a superfluous and unnatural weight of side branches, they were

growing tall, and in a generally healthy and rapid-growing state;

therefore, seeing this, I cut close to the main stem or part which

formed the trunk, all those stumps which I formerly shortened to four

inches, and in regulating the tops of the young trees, I merely

shortened such shoots as had the appearance of ultimately gaining

strength upon the main top shoot. With regard to my reason for not

having cut away the strong shoots or branches from the main stem when I

first pruned those trees, I have to observe, that had I cut them away at

the first course of priming clean to the bark of the trunk, the

consequence would have been that the sap of the young trees in its

ascent would have been arrested at the cut parts, young sapling shoots

would have been formed upon the stem immediately under the cuts, and the

general health of the trees would have been injured from the sap not

rising unchecked to the top shoots: these evils were avoided simply by

cutting off a large portion of each large branch, and leaving a small

portion of each upon the stem, in order to continue the regular flow of

the sap to that part, and which, from being partially weakened in the

branches, was proportionately forced to flow upwards to the supply of

the top parts of the trees; after this had taken place, the stumps were

cut away without doing any injury to the trees. By this method of

pruning off parts of large branches from a tree, I have often brought

unhealthy trees to a state of sound health; and as soon as I observed

that such trees had regained their health, which is at once observable

by their making vigorous shoots of young wood in the top branches, I

immediately cut away the parts of the branches that were left, when the

wounds were soon made up by the extra supply of proper woody matter,

which increased with the health of the trees ; but this cure is only

applicable to trees in a young state. I have succeeded in effecting it

upon trees under twenty years old.

After pruning the oak plantation in the way just detailed, I next set to

the pruning of another oak plantation of about twenty years’ standing.

This other plantation of oaks was situated in a rather sheltered part of

the estate; and from having been nursed by Scots firs, many of which

were growing when I commenced pruning operations there, the oak trees

were very much drawn up. I observed that the oaks had never been either

thinned or pruned, and consequently were growing within four feet of one

another—that being the distance at which they had been originally

planted. As the situation was a sheltered one, I thinned out a few of

the Scots firs, and also a few of the oaks, previous to commencing to

prune; and when I had those removed, and the trees standing more upon

their own weight, 1 saw that they were, from the effects of having been

drawn up, very slender, and not able to stand much exposure or much

cutting in the way of pruning, although they were from eight to fifteen

feet in height; and seeing them in this delicate state, I only shortened

a few of the stronger side branches below, and at the same time

shortened a few top branches upon each tree as I found it necessary, in

order that they might be properly balanced, and that the wind might not

have much power upon them. In this state I left them for two years, when

I again examined the trees, and finding that they had improved in a

remarkable manner, I again set to work and gave them a final pruning. I

have seldom found any plantation make sueh an improvement as this one

did during the two years that I allowed it to recover itself before

giving it a final course of pruning : this was owing to the gradual

manner in which I thinned out a few trees, and cut off a part of the

branches as a preparation for pruning. This is what every forester ought

particularly to attend to; for, had I foolishly and thoughtlessly

commenced to prune severely at first, it was quite possible that every

tree in the plantation might have been thrown into an unhealthy

state,—which, indeed, I have more than once seen done;—but by having

gone cautiously to work, I had the satisfaction, at the end of two years

from the time that I first examined those trees, to find them not only

stiff, healthy, tall trees, but in a most vigorous state of growth also

; and, finding them in such a state, I pruned them upon the same

principle as stated in the former case—that is, I pruned off all the

branches to one-third the height of the tree in each case, in order to

form a clean trunk; and above this, among the top branches, I merely

shortened such as had the appearance of gaining strength upon the top.

And wherever two distinct tops occurred in one individual tree, I cut

off one, always leaving the one which appeared the most strong and

healthy, and which issued most directly from the centre of the system of

the tree, although in many cases it did not take an upright direction;

for let it be observed, that an oak tree is the more valuable for having

a bend in its form, such trees being useful in ship-building.

In a similar manner I have pruned plantations of thirty years’ standing;

but in the case of pruning at such an advanced age, no branch should be

cut from the trunk that exceeds three inches in diameter, if it is

intended that the timber should be of value when of full age; and even

where such branches are to be taken off, they should be shortened in one

year and cut clean off the year following, by which precaution the

vessels which convey the sap to the branch receive a gradual check, and

are to a considerable extent deadened before the complete amputation

takes place, and consequently the body of the tree is not injured by

such gradual treatment. And again, this is in a great measure influenced

by the nature of the situation upon which the trees may be growing. If

trees growing upon a high and exposed situation are not properly pruned

when they are young, they will not admit of much pruning when above

fifteen years old; in such a situation the sap of the trees always flows

slowly as compared with others in a sheltered spot, and seeing this,

pruning ought to be avoided in such a situation when the trees are about

ten years old. Trees growing in a sheltered situation are generally in a

vigorous state of growth under thirty years of age; consequently, under

skilful management, pruning may be advantageous to trees in such a

situation at any time under that age; but in all cases pruning should be

avoided as much as possible as the trees advance above ten years of age.

I have seen foresters practise the pruning of fir-trees ; such a

practice is, however, the worst imaginable. The value of a fir-tree is

greatly deteriorated by its being pruned; where the branch was cut off,

the tree generally loses much of its sap, and is very apt to fall into

bad health ; and when such a tree is cut for timber, the pruned knots

always fall out of the wood, causing holes, and consequently rendering

such timber almost of no value.

In all cases pruning operations arc seldom found necessary to any

considerable extent, where the plantations are attended to in the way of

properly thinning them. When hard-wood trees are grown pretty close to

one another, and particularly with a proportion of firs to nurse and

draw them up rather tall than otherwise, we always find the most perfect

and sound timber trees; therefore it is from this circumstance that many

foresters have maintained that pruning should not be practised at all,

and such a state of management is unquestionably the best. But how can

this be maintained in all cases? I have known many plantations wherein

firs and hard wood were planted originally, but in consequence of the

firs having died out, the hard-wood trees were left alone upon the

ground at a pretty wide distance from one another, and in this case they

spread themselves widely to branches; consequently, in order to check

such a tendency, pruning was absolutely necessary, and this I have

frequently done myself, and found its effect most beneficial. Hence many

foresters, from having only such sort of plantations to deal with, and

not having experienced the effects of a more healthy state of things,

have recommended pruning as necessary in all cases. And this brings me

to say in conclusion upon this head, that a forester, in order to be so

profitably, should be able to judge for himself how far pruning is

advisable in one case and not so in another; he must take into

consideration the situation the trees are growing upon—and if it be a

high one he should prune very little indeed, and if a low situation he

may use the knife more freely. If the plantation to be pruned has been

attended to formerly, there will be very little difficulty in putting it

into proper order; but if it has been neglected, great caution must be

exercised in order not to expose the trees suddenly by taking off too

many branches at once. If the plantation he a young one, the trees may

be made to improve although they may have been previously neglected; but

if an old one, the chances of improvement by pruning are small. |