|

As usual with me at the opening of spring, the

garden received our first attention. Dick covered it heavily with manure,

cleared it up and made all ready for wife and daughter. This year we had

no seeds to purchase, having carefully laid them aside from the last. In

order to try for myself the value of liquid manuring, I mounted a barrel

on a wheelbarrow, so that it could be turned in any direction, and the

liquor be discharged through a sprinkler with the greatest convenience.

Dick attended faithfully to this department. As early as January he had

begun to sprinkle the asparagus; indeed he deluged it, putting on not less

than twenty barrels of liquor before it was forked up. It had received its

full share of rich manure in the autumn: the result of both applications

being a more luxuriant growth of this delightful vegetable than perhaps

even the Philadelphia market had ever exhibited. The shoots came up more

numerously than before, were whiter, thicker, and tenderer, and

commanded

five cents a bunch more than any other. As the bed was a large one, and

the yield great, we sold to the amount of $21. I certainly never tasted so

luscious and tender an article. Its superiority

was justly traceable, to some extent, to the liquid manure.

The same stimulant was freely administered all over

the garden, and with marked results. It was never used in dry weather, nor

when a hot sun was shining. We contrived to get it on at the beginning of

a rain, or during drizzly weather, so that it should be immediately

diluted and then carried down to the roots. I have no doubt it promoted

the growth of weeds, as there was certainly more of them to kill this

season than ever before. But we had all become reconciled to the sight of

weeds—expected them as a matter of course—and my wife and Kate became

thorough converts to Dick's heresy as to the impossibility of ever

getting rid of them. I was pained to hear of this declension from what I

regarded as the only true faith; but when I saw the terrible armies which

came up in the garden just as regularly as Dick distributed his liquor, I

confess they had abundant reason for the faith that was in them.

But the barnyard fluid was a good thing,

notwithstanding. It brought the early beets into market ten days ahead

of all competitors, thus securing the best prices. It was the same with

radishes and salad. The latter is scarcely ever to be had in small country

towns, and then only at high rates. But whether it was owing to the liquor

or not, I will not say, but it came early into market in the best

possible condition; and as there happened to be plenty of it, we sold to

the amount of $19 of the very early, and then, as prices lowered,

continued to send it to the store as long as it

commanded two cents a head, after which the cow and pigs became exclusive

customers. The fall vegetables, such as white onions, carrots and

parsnips, having had more of the liquor, did even better, for they grew to

very large size. It was the same thing with currants and gooseberries. The

whole together produced $83; to which must be added the ten peach-trees,

all which I had thinned out when the fruit was the size of hickory nuts,

and with the same success as the previous year. This was in 1857, that

time of panic, suspension, and insolvency. That year had been noted, even

from its opening, as one of great scarcity of money in the cities, when

all unlucky enough to need, it were compelled to pay the highest rates

for its use. But we in the country, being out of the ring, gave way to no

panic, felt no scarcity, experienced no insolvency. Peaches brought as

high a price as ever; as, let times in the city be black as they may,

there is always money enough in somebody's hands to exchange for all the

choice fruit that goes to market. The fruit from the ten trees produced me

$69, making the whole product of the garden $152. I thought this was not

doing well enough, and resolved to do better another year.

At the usual season for the weeds to show

themselves on the nine acres, it very soon became evident that two years'

warfare had resulted in a comparative conquest. It may be safely said that

there was not half the usual number, and so it continued throughout the

season. But no exertion was spared to keep them

under, none being allowed to go to seed. This watchfulness being continued

from that day to this, the mastery has been complete. We still have weeds,

but are no longer troubled with them as at the beginning. The secret lies

in a nutshell—let none go to seed. Nor let any cultivator be discouraged,

no matter how formidable the host he may have to attack at the beginning.

But if he will procure the proper labor-saving tools, and drive them with

a determined perseverance, success is sure.

As usual, the strawberries came first into market,

and were prepared and sent off with even more care than formerly. The

money pressure in the cities caused no reduction in price, and my net

receipts were $903. An experienced grower near me, with only four acres,

cleared $1,200 the same season. His crop was much heavier than mine. If he

had practised the same care in assorting his fruit for market, he would

have realized several hundred dollars more. But his effort was for

quantity, not quality.

A portion of the raspberries had been thoroughly

watered with the liquid manure, all through the colder spring months. It

was too great a labor, with a single wheelbarrow, to supply the whole two

acres, or it would have been similarly treated. But the portion thus

supplied was certainly three times as productive as the portion not

supplied. My whole net receipts from raspberries amounted to $267. The

plants were now well rooted, and were in prime bearing condition. Since

this, I have quadrupled my facilities for applying the liquid manure. A

large hogshead has been mounted on low wheels, the rims of which

are four inches wide, so as to prevent them sinking into the ground, the

whole being constructed to weigh as little as possible. The sprinkling

apparatus will drench one or two rows at a time, as may be desired. The

driver rides on the cart, and by raising or lowering a valve, lets on or

shuts off the flow of liquor at his pleasure. Having been

based on the raspberries for several years, I

can testify to the extraordinary value of this mode of applying manure. It

stimulates an astonishing growth of canes, increases the quantity of

fruit, while it secures the grand desideratum, a prodigious enlargement in

the size of the berries. I find by inquiry among my neighbors that none of

them get so high prices as myself. Every crop has been growing more

profitable than the preceding one; and it may be set down that an acre of

raspberries, treated and attended to as they ought to be, will realize a

net profit of $200 annually. The Lawtons were this year to come into

stronger bearing. Parties in New York and Philadelphia had agreed to take

all my crop, and guarantee me twenty-five cents a quart. One speculator

came to my house and offered $200 for the crop, before the berries were

ripe. I should have accepted the offer, thinking that was money enough to

make from one acre, had not my obligation to send the fruit to other

parties interfered with a sale. But I made out a trifle better, as the

quantity marketed amounted to 896 quarts, which netted me $206.08. In

addition to this, the sales of plants amounted to $101. As the

market price for plants was falling, I was not anxious to multiply

them to the injury of the fruit; hence many suckers were cut down outside

of the rows, so as to throw the whole energy of the roots into the

berries; and I think the result justified this course. The demand for the

fruit was so great, that I could have readily sold four times as much at

the same price. As the season for the blackberries closed, all the stray

fruit was gathered and converted into an admirable wine. Some seventy

bottles were made for home use; and when a year old, I discovered that it

was of ready sale at half a dollar per bottle. Since then we have made a

barrel of wine annually; and when old enough, all not needed for domestic

purposes is sold at $2 per gallon. It is a small item of our general

income, but quite sufficient to show that vast profit may be made by any

person going largely into the business of manufacturing blackberry-wine.

We raised

nothing of value among the blackberries this year. The growth of new wood

had been so luxuriant, that the ground between the rows was too much

shaded to permit other plants to mature. In some places, the huge canes,

throwing out branches six to seven feet long, had interlocked with each

other from row to row, and were cut away, to enable the cultivator and weeder to pass along between them, and thenceforward this acre was given

up entirely to the blackberries. As the roots wandered away for twenty or

thirty feet in search of nourishment, they acquired new power to

force up stronger and

more numerous canes. Many of these came up profusely in a direct line with

the original plants. When not standing too close together, they were

carefully preserved, when of vigorous growth; but the feeble ones were

taken up and sold. Thus, in a few years, a row which had been originally

set with plants eight feet apart became a compact hedge, and an acre

supporting full six times as many bearing canes as when first planted.

Hence the crop of fruit should increase annually. It will continue to do

so, if not more than three vigorous canes are allowed to grow in one

cluster; if the canes are cut down in July to three or four feet high; if

the branches are cut back to a foot in length; if the growth of all

suckers between the rows is thoroughly stopped by treating them the same

as weeds; if the old-bearing wood is nicely taken out at the close of

every season; and, finally, if the plants are bountifully supplied with

manure. From long experience with this admirable fruit, I lay it down as a

rule that every single condition above stated must be complied with, if

the grower expects abundant crops of the very finest fruit. Observe them,

and the result is certain; neglect them, and the reward will be inferior

fruit, to sell at inferior prices.

To the Lawtons succeeded the peaches, now their

first bearing year. We had protected them for three seasons from the fly

by keeping the butts well tarred, and they were now about to give some

return for this careful but unexpensive oversight. Some few of

them produced no fruit whatever, but the majority made a

respectable show. I went over the orchard myself, examining each tree with

the utmost care, and removed every peach of inferior size, as well as

thinning out even good ones which happened to be too much crowded

together. Being of the earlier sorts, they came into market in advance of

a glut; and though the money-pressure in the cities was now about

culminating in the memorable explosion of September, yet there was still

money enough left in the pockets of the multitude to pay good prices for

peaches. It is with fruit as it is with rum—men are never too poor to buy

both. My 804 trees produced me $208 clear of expenses, with a pretty sure

prospect of doing much better hereafter. I had learned from experience

that a shrewd grower need not be apprehensive of a glut; and that if

panics palsied, or a general insolvency desolated the cities, they still

contrived to hold as much money as before. Credit might disappear, but the

money remained; and the industrious tiller of the soil was sure to get his

full share of the general fund which survives even the worst convulsion.

My acre of tomatoes netted me this year $192, my

pork $61, my potatoes $40, and the calf $3. Thus, as my grounds became

charged with manure,—as I restored to it the waste occasioned by the crops

that were removed from it, and even more than that waste,—so my crops

increased in value. It was thus demonstrable that manuring would pay. On

the clover-field the most signal evidence of this was

apparent. After each cutting of clover had been taken to the

barnyard, the liquor-cart distributed over the newly mown sod a copious

supply of liquid manure, thus regularly restoring to the earth an

equivalent for the crop removed. It was most instructive to see how

immediately after each application the well-rooted clover shot up into

luxuriant growth. I have thus mowed it three times in a season, and can

readily believe that in the moister climate of England and Flanders as

many as six crops are annually taken from grass lands thus treated with

liquid manure. Indeed, I am inclined to believe that there is no

reasonable limit to the yield of an acre of ground which is constantly and

heavily manured, and cultivated by one who thoroughly understands his art.

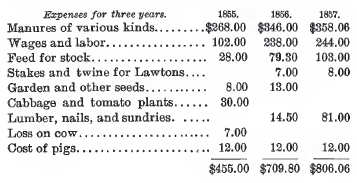

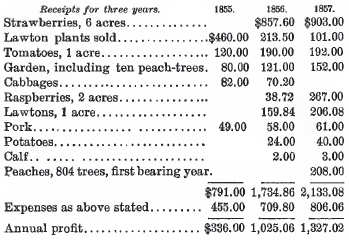

Three years' experience of profit and loss is quite

sufficient for the purpose of this volume. It has satisfied me, as it

should satisfy others, that Ten Acres are Enough I give the following

recapitulation for convenience of reference:

This result may surprise many not conversant with

the profits which are constantly being realized from small farms. But

rejecting the income from the sale of plants, the pigs, and the calf, as

exceptional things, and the profit of the nine acres for the first year

will be found to be nothing per acre, for the second year, $83.50, and for

the third, $129.10. But there are obvious reasons why this should be so.

The ground was crowded to its utmost capacity with those plants only which

yielded the very highest rate of profit, and for which there was an

unfailing demand. In addition to this, it was cultivated with the most

unflagging industry and care. Besides using the contents of more than one

barnyard upon it, I literally manured it with brains. My whole mind and

energies were devoted to improving and attending to it. No city business

was ever more

industriously or

intelligently supervised than this. But if the reward was ample, it was no

greater than others all around me were annually realizing, the only

difference being that they cultivated more ground. While they diffused

their labor over twenty acres, I concentrated mine on ten. Yet, having

only half as much ground to work over, I realized as large a profit as the

average of them all. Concentrated labor and manuring thus brought the

return which is always realized from them when intelligently combined.

For six years since 1857 I have continued to

cultivate this little farm. Sometimes an unpropitious season has cut down

my profits to a low figure, but I have never lost money on the year's

business. Now and then a crop or two has utterly failed, as some seasons

are too dry, and others are too wet. But among the variety cultivated some

are sure to succeed. Only once or twice have I failed to invest a few

hundred dollars at the year's end. All other business has been studiously

avoided. I have spent considerable money in adding to the convenience of

my dwelling, and the extent of my outbuildings; among the latter is a

little shop furnished with more tools than are generally to be found upon

a farm, which save me many dollars in a year, and many errands to the

carpenter and wheelwright. The marriage of my daughter Kate called for a

genteel outfit, which she received without occasioning me any

inconvenience. I buy nothing on credit, and for more than ten years have

had no occasion to give a note. If at the year's end we are found to

owe anything at the stores, it is promptly paid. As means increased, my

family has lived more expensively though I think not any more

comfortably.

I do

not deserve more than others, but thankful that God has given me more. I

rise in the morning with an appetite for labor as keen as that for

breakfast. But others can succeed as well as myself. Capital or no

capital, the proper industry and determination will certainly be rewarded

by success.

|