|

FOREWORD

Far

up in the frozen north, across the heaving Atlantic from ice-bound

Labrador, subject to the long Arctic twilight and lighted by the rays of

the polar star, sit the giant, heather-clad mountains of the Lion of the

North. Around their never-changing buttresses mists gather, storms break

and snows beat, and out of those mists, storms and snows, has come a

race of people to whom the civilized world owes much. Far

up in the frozen north, across the heaving Atlantic from ice-bound

Labrador, subject to the long Arctic twilight and lighted by the rays of

the polar star, sit the giant, heather-clad mountains of the Lion of the

North. Around their never-changing buttresses mists gather, storms break

and snows beat, and out of those mists, storms and snows, has come a

race of people to whom the civilized world owes much.

In

all Europe, in fact in all the world, there is no more extraordinary

anthropological spectacle than that presented by the Gaels of Scotland

who preserve, to the the present time, the manners and customs of their

ancestors from ages the most remote, and use a language once the most

widely diffused and now the oldest extant. Among all the peculiarities

of times past which they preserve there is none more picturesque than

that of the Highland costume, now also the oldest garb in use.

So

ancient is its origin that its beginning is lost in the mists of

antiquity, yet the Highlanders cling to it with a tenacity which speaks

well for its existence when the Great Trump sounds forth and time shall

be no more. Oriental in its flowing characters it is worn by men with

far more than Oriental bravery.

In

the Crimean War the Russians said, "The English were bad enough but

their wives were devils"; and Napoleon, after Waterloo, declared, "If

they had only kept those-women devils at home I could have won the

battle."

So,

it is with a feeling of pardonable pride because of my Scottish blood

that I take up my pen to indite "Wild Scottish Clans," a book which will

partly show from what scenes Scotia's sons derive their hardihood. It is

also with the just hope of its being acceptable wherever honor, truth,

steadfastness, devotion and bravery are revered that the author affixes

his name.

Arthur Llewellyn Griffiths.

(A Macgregor).

Portland, Maine, June I, 1910.

As the spark of life was

slowly diminishing in the immortal Minstrel of the Border, those who

stood beside the bed of his dissolution at Abbotsford, saw his lips

move. Bending low to catch the voice's last utterance they heard the

words of one of his own songs of longing for the heather and bonnie

Prince Charlie.

Alan Stewart, Scottish

hero of Stevenson's "Kidnapped," said of his father, "He left me my

breeks to cover me and little besides. And that was how I came to

enlist, which was a black spot upon my character at the best of times,

and would still be a sore job for me if I fell among the redcoats."

"What," cried David

Balfour, "were you in the English army?"

"That was I," replied

Alan, 44 but I deserted to the right side at Prestonpans and that's

some comfort."

"Dear, dear!" exclaimed

Balfour, "The punishment is death."

"Ay," returned Alan, "if

they got hands on me it would be a short shrift and a lang tow for Alan!

But I have the King of France's commission in my pocket, which would aye

be some protection."

"I misdoubt it much," I

spoke up.

"I have doubts mysel',"

said Alan, drily.

"And, good heaven, man! "

cried I, "you that are a condemned rebel and a deserter, and a man of

the French king's what tempts ye back into this country? It's a

braving of Providence."

"Tut!" answered Alan, "I

have been back every year since "The '45 ' " meaning the year of

Culloden.

"And what brings ye,

man?" I asked.

"Well, ye see, I weary

for my friends and country," he admitted. "France is a braw place, nae

doubt but I weary for the heather and the deer."

Such love for and

devotion to Scotland permeate the high and the lowly. A Scottish lassie

came to this country to earn money to support her aged parents.

Homesickness depleted her health. Consumption seized her in its fell

grasp. Friends of her staunch character gathered around her bedside. She

had but one wish when she finally knew that she must pass beyond.

"Oh, if I could but see

the bonnie hills o' Scotland before I die!" she often sighed. Her

friends collected money to send her home. On the homeward voyage it

became apparent that she could not live to see the "bonnie hills o4

Scotland."

One evening, just as the

sun was setting, they took her on deck to show her the days dying glory.

She gazed at it, enraptured, and then sank back with a sigh, saying,

"Oh, but it's not sae fine as the bonnie hills o4 Scotland."

There was a pause in

which the onlookers stood reverently by. Then the dying girl suddenly

lifted herself on her elbow and exclaimed, excitedly, "Oh, I see them

noo!"then a look of surprise overspread her features, an expression of

ecstasy came "but I didna ken it was the hills o' Scotland where the

horsemen and the chariots were!" and she passed into that Land of Glory,

the hills of which she had seen and had hardly differentiated from "the

bonnie hills o' Scotland!"

Lord Byron, George Gordon

by name, himself of Scottish family, has immortalized his heart

yearnings for his father's land by the passionate lines of Lochnagar

addressed to one of the very grandest of the northern mountains around

the beetling crags of which the eagle, king of birds, soars.

"Away, ye gay landscapes,

ye gardens of roses,

In you let the minions of luxury rove;

Restore me the rocks where the snowflake reposes.

If still they are sacred to freedom and love.

Yet Caledonia, dear are thy mountains,

Round their white summits tho' elements war,

Tho' cataracts foam 'stead of smooth flowing fountains,

I sigh for the valley of dark Lochnagar.

"Ah, there my young

footsteps in infancy wandered,

My cap was the bonnet, my cloak was the plaid;

On chieftains departed my memory pondered,

As daily I strayed thro' the pine-covered glade.

I sought not my home till the day's dying glory

Gave place to the rays of the bright polar star,

For fancy was cheered by traditional story,

Disclosed by the natives of dark Lochnagar.

"Shades of the dead! have

I not heard your voices

Rise on the night rolling breath of the gale?

Surely the soul of the hero rejoices,

And rides on the wind o'er his own Highland vale.

Round Lochnagar, while the stormy mist gathers.

Winter presides in his cold, icy car;

Clouds there encircle the forms of my fathers;

They dwell 'mid the tempests of dark Lochnagar.

"Years have rolled on,

Lochnagar, since I left you,

Years must elapse ere I see you again;

Though nature of verdure and flowers has bereft you,

Yet still thou art dearer than Albion's plain.

England, thy beauties are tame and domestic

To one who has roved on the mountains afar;

Oh! for the crags that are wild and majestic,

The steep, frowning glories of dark Lochnagar."

Across the sea I look and

see in a vision that bonnie land where day is long, the lark sings the

song of freedom up the glen, the rays of the cold polar star guard by

night, where

"The heath waves wild upon

her hills,

And foaming frae the fells,

Her fountains sing o' freedom still,

A» they dance down the dells.

And weel I lo'e the land, my lads,

That's girded by the sea;

Then Scotland's vales, and Scotland's dales

And Scotland's hills for mel

"The thistle wags upon the

fields

Where Wallace bore his blade

That gave her foeman's dearest bluid

To dye her auld grey plaid;

And, looking to the lift, my lads,

I sing this doughty glee:

Aula Scotlanas right, and Scotland's might.

And Scotland's hills for me!

"They tell o' lands with

brighter skies

Where freedom's voice ne'er rang:

Gie me the hills where Ossian dwelt,

And Coila's minstrel sang!

For I've nae skill o' lands, my lads,

That ken na to be free!

Then Scotland's right, and Scotland's might,

And Scotland's hills for me! "

"I will lift up mine eyes

unto the hills, from whence cometh my help," sang the inspired Psalmist,

and from the hills come the greatest fighting men of the world, for

freedom is bred in their very bones. The auld grey plaid of Scotland has

been stained red scores of times when her braw Highlanders have come

down from their mountain fastnesses to revel in the blood of her

enemies. Scotland stands today the only un-conquered land in the world

and the claymore the only unconquered sword on earth. The Highlands of

Scotland stopped the world-conquering Romans' northward advance, and the

wild men of the glens and hills would have exterminated Caesar's legions

had they not hastily constructed a great earthen defence, traces of

which can be seen to this day.

When feudalism rode on

the neck of all Europe in the Dark Ages, it made no encroachments on the

mountains of Scotland and alone in those savage glens was the lamp of

freedom kept from total extinction.

Though Wallace, like the

Saviour, was betrayed for a price and his body dismembered and scattered

to the four corners of the kingdom his soul is marching on. Like the

Saviour, Wallace died of a broken heart, for when the noose was just to

be placed around his neck by his would-be murderers, God instantly

removed him from mortality. Even so the Victim of the cross, weighed

down by the sins of an ungrateful world, gave up the ghost under the

weight.

Directly to the south of

Stirling Castle, most sacred in Scottish history, is Scotland's most

glorious field of Bannockburn. Toward the close of the year 1313,

Stirling Castle was closely besieged by Robert Bruce who made a bargain

with its governor that if not relieved by St. John's Day June 24th of

the following year it should be surrendered to the Scots.

This was the last hold of

England on the sacred soil of Scotland after the liberation brought

about by Wallace. Therefore England aroused herself to a supreme effort;

every resource was strained to the utmost, and a mighty host a hundred

thousand is the number given led by Edward II in person, poured

through the Border Country and in June, 1314, encamped to the north of

Tor wood. Robert Bruce had in the meantime been actively preparing his

defences, and after some preliminary skirmishing and feats of arms the

battle so memorable for Scotland was fought on St. John's Day, the

English advancing confidently to the attack at daybreak.

"At Bannockburn the

English lay, The Scots they were not far away, But waited for the

breaking day That glinted in the east. At last the sun broke through the

heath And lighted up that field of death, When Bruce, with

soul-inspiring breath, His heroes thus addressed:

"Scots wha hae wi' Wallace

bledl

Scots wham Bruce has aften led!

Welcome to your gory bed, Or to victory!

Now's the day and now's the hour,

See the front of battle lower,

See approach proud Edward's power:

Chains and slavery!

"'Wha sae base as be a

slave:

Wha would fill a coward's grave:

Wha would be a traitor knave:

Let him turn and flee!

Wha for Scotland's king and law,

Freedom's sword will strongly draw,

Freeman stand or freeman fa'.

Let him on wi' me!

"'By oppression's woes and

pains.

By our sons in servile chains,

We will drain our dearest veins,

But they shall be free!

Lay the proud usurpers low

Tyrants fall in every foe,

Liberty's in every blow:

Let us do or dee!' "

The numbers of the

Scottish army did not exceed thirty thousand men but, according to a

tradition, the sacred corpse of Wallace was there. Bruce led the reserve

and all determined to make this division the stay of their little army

or the last sacrifice for Scottish liberty and its martyred Wallace's

corpse. There stood the sable hearse of Wallace. "By that heaven-sent

palladium of our freedom," cried Bruce, pointing to the hearse, "we must

this day stand or fall. He who deserts it murders William Wallace anew!

"

The Abbot of Inchaffray

passed along in front of the Scots, barefoot and with the crucifix in

his hand, imploring the favor of heaven on the cause of freedom, and

exhorting the Scots to fight for their rights, their king and the corpse

of William Wallace. The Scots fell on their knees to confirm their

resolution with a vow.

The sudden humiliation of

their posture incited an instant triumph in the mind of Edward; and,

spurring forward, he shouted aloud, "They yield! They cry for mercy!"

"They cry for mercy," returned Lord Percy, "but not from us. On that

ground on which they kneel they will be victorious or find their

graves!"

Proud Edward had yet to

learn that

"No stride was ever bolder

Than his who showed the naked leg

Beneath the plaided shoulder."

The battle was commenced

by rapid discharges of the terrible clothyard arrows by the English

archers. So great was the number discharged that they darkened the air.

Their accuracy and destructive power were formidable. Bruce ordered the

Scottish horse to charge the Southron archers and the latter were swept

from the field. The English horse returned the charge and, ignorant of

the nature of the ground wisely chosen by the Scots, stumbled and sank

to their deaths in the morass.

The spectacle from the

Borestane where King Robert stood was most awful. Among the fighting

thousands on the plain could be made out here and there the figure of

some well-known Scottish leader driving a spattered battleaxe through

iron and bone and brain at every blow.

Above the thunderous

crash of steel on steel, the shrieks of agony and torture, and the yells

of vengeance, there rose from time to time the battle cries of the great

Scottish clans.

Column after column of

Edward's forces came on to crash, break and disappear beneath the long

Scottish lances and sweeping Lochaber hills.

Before the onslaught of

those wild sons of freedom the hireling host fell in heaps; they wavered

as the heaps of dead rose ever higher before them, and the Scottish

soldiers, perceiving the hesitation, cried, "On them!

On them! They fail! " The

wild yells of the savage Scots terrorized them and there ensued one of

those inexplicable scenes of panic and terror when a vastly superior

force of trained men breaks and flees, as though life at all costs were

the one thing to be considered.

Edward II with five

hundred soldiers all that was left of that great host fled from the

field and got refuge at Dunbar, the scene of the unfortunate battle

which had temporarily given England the supremacy. From Dunbar he went

by boat to Berwick. He looked upon his personal escape as miraculous and

vowed he would build a house for poor Carmelites. This vow he fulfilled

by founding Oriel College, Oxford, which thus remains today a monument

to Bannockburn and the emancipation of Scotland.

Thereafter the victorious

war pipes could be heard wildly skirling in many a savage glen, "The

Cock o* the North," to cheer the Scottish soldier on many a hard-fought

field. Bruce won a crown, welded a heterogeneous people into one, and

exacted a treaty from Edward II insuring what he had won.

The passions of the

Gaelic feudalism of those times could not be restrained from atrocious

acts even in moments of common misfortune. On the fatal field of Flodden

it is related of a Highlander of the Clan Mackenzie that he heard those

near him exclaiming, "Alas, Laird, thou hast fallen!"

"What laird?" shouted the

Mackenzie.

In the answer, "The Laird

of Buchanan!" he heard a name with which his clan had a feud of blood.

Then and there the "Faithful Highlander," as he is called by the

sympathetic historian, sought out the fallen laird, found that he was

only wounded, and butchered him.

Clan Mackenzie suffered

severely in a long-standing feud with the Macleods of Skye when both

clans were reduced to the verge of ruin and lived on horses, dogs and

cats, as they had no time or men to provide better food. Clan Mackenzie

on one fatal morning packed the Kirk of Gilchrist for worship. It was in

1603, the year of the accession of James VI of Scotland to the English

crown. A prowling band of the Macdonalds of Clanranald discovered them,

set fire to the kirk, guarded the entrance with claymores and burned to

death the entire congregation of Mackenzies. But the Macleods had

something to say to the Macdonalds. The Macdonalds of Eigg were caught

by the Macleods in a cave. There were two hundred Macdonalds within the

cave the entire population of the island. The Macleods barred the

entrance, built a fire and smoked the Macdonalds to death. Sir Walter

Scott visited the cave two hundred and eleven years later and the bones

of the victims still covered the floor.

The Battle of Harlaw in

1411 decided that Gaelic should be supreme over Teutonic in Scotland.

The haughty, contemptuous feeling of the Norman nobility towards the

unmailed Highlanders is well expressed in the Ballad of Harlaw. The

brave appearance of the two hundred mailed knights is spoken of and then

"They had na ridden a

mile, a mile,

A mile, but barely ten,

When Donald came branking down the brae

Wi' twenty thousand men.

Their tartans they were waving wide,

Their glaves were glancing clear,

Their pibrochs rang frae side to side

Would deafen ye to hear."

The Earl of Glenallen,

startled at the unexpected size of the enemy's force, consulted his

squire as to what it were best to do, and the instant reply was,

"If they hae twenty

thousand blades,

And we twice ten times ten,

Yet they hae but their tartan plaids

And we are mail-clad men."

But before the battle was

over the haughty ones fled from those tartan plaids.

The Macdonalds got into

still further trouble, this time with the Macleans of Duart. In 1598

Lachlan Maclean from the castle on the coast of Mull fought in the

dreadful clan battle of Lochgruinard against the Macdonalds in Islay,

when he was slain, courageously fighting, with eighty of the principal

men of his kin and two hundred clansmen lying dead about him. This clan

mustered five hundred claymores in "The 45" and they were in the front

line at Culloden. Subsequently the Macleans of Duart and the Maclaines

of Lochbuie fought a pitched battle near Lochbuie. The Macleans of Duart

were defeated. Duart, when returning home after the battle, fell in with

Lochbuie, who was sleeping along with some of his men. Surely here was a

chance for vengeance placed super-naturally in the way. Maclean of Duart

had been defeated by the very men now sleeping before him.

Aytoun says,

"Nowhere beats the heart

so kindly

As beneath the tartan plaid."

Maclean of Duart drew his

dagger, twisted it in the hair of his enemy, and then left him. When

Maclaine awoke in the morning and found his hair fastened to the ground,

he recognized the dirk, and the two families were friends ever after.

Nearly one hundred years

later the great battle of Killiekrankie was fought. The object of the

battle was to capture Blair Castle from the Highlanders for it commanded

the pass which is the key to the central Highlands. It was in the early

morning of July 27, 1689 that the mixed army of Lowland Scots, Dutch and

English entered the defile of Killiekrankie. Killiekrankie was deemed

the most perilous of all those dark ravines through which the marauders

of the hills were wont to sally forth. A horse could be led up only with

great difficulty and he who lost his footing had no hope of life.

Through the gorge Mackay led his troops unopposed and then placed them

as best the nature of the ground would permit.

On the north, Graham of

Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee, could be seen halting his Highlanders on

the brow of a hill. Two hours went by while the sun was passing out of

the eyes of the Highlanders, then Claver-house ordered the charge and

the dreaded bagpipes rounded the war skirl.

The Highlanders advanced

in their usual fashion divested of their plaids, with bodies bent

forward and nearly covered by their targets. On coming close to the

enemy's front ranks they fired and threw away their pieces, then,

setting up a wild yell, they hurled themselves forward, claymore in

hand. Breaking through the advance guard, they carried terror and panic

into the body of the enemy, and before many minutes the battle was

decided in favor of the defending Highlanders. All was over and a

mingled torrent of redcoats and tartans went raving down the valley to

the Gorge of Killiekrankie.

"Like a tempest down the

ridges

Swept the hurricane of steel,

Rose the slogan of Macdonald,

Flashed the broadsword of Lochiel!

Horse and man went down before us,

Living foe there tarried none

On the field of Killiekrankie

When that stubborn fight was done! "

The two Scottish families

of Gordon and Grant had been old-time allies. The Earl of Huntly,

wishing to chastise the Farquharsons for the killing of a Gordon,

arranged with the Laird of Grant that the latter should advance down the

Dee Valley simultaneously with his own approach from the other end, so

as to shut the Farquharsons in between two fires.

The surprise was so

complete that the unfortunate Clan was nearly exterminated and an

enormous number of children made orphans and homeless. These, Huntly

took home where they were treated so much like animals that in time they

grew to be like them. It is alleged that the head of the Grants, about a

year later, was shown for his amusement a long wooden trough outside the

kitchen into which all the cold scraps and odds and ends from the table

had been thrown. At a given signal a door was opened and a troop of

little half naked savages rushed in, and falling on the trough, fought

and tore for the food. Grant was greatly shocked on being told that

those were the orphans he had helped to make. He got Huntly's permission

to take them away with him, saw to their care and training, and

gradually they became absorbed into his clan.

About this time these

victorious Gordons got into difficulties with the Forbes. A meeting

between the two clans took place for the purpose of making an amicable

settlement. The difference being made up, both parties sat down to a

feast.

"Now," said Gordon to the

Forbes chief, "as this business has been satisfactorily settled, tell

me, if it had not been so, what was your intention?"

"There would have been

bloody work," returned Forbes, "bloody work; and we should have had the

best of it. I shall tell you. See, we are mixed, one and one, Forbes and

Gordons."

The Gordon chief looked

around the gathering and beheld that it was as his companion had said.

Forbes resumed, "I had

only to give a sign by the stroking down of my beard, and every Forbes

was to draw the dirk from under his left arm and stab to the heart his

right-hand man."

As he spoke, Forbes

suited the action to the word and stroked down his flowing beard. In a

moment, a score of dirks were out, in another moment they were buried in

as many Gordon hearts, for the Forbes, mistaking the motion for the

agreed-upon sign of death, struck their weapons into the bodies of the

unsuspecting clansmen.

The two chiefs looked at

each other in silent consternation. At length Forbes said, "This is a

sad tragedy we little expected, but what is done cannot be undone, and

the blood that now flows on the floor will just help to slacken the auld

fire of Corgarf!" He referred to a time when the Gordons burned out the

Forbes.

During the reign of James

I, the Macnabs had suffered from the plunderings of a robber band of the

Macnishes. More than once the old Macnab chief had vowed vengeance but

the Macnishes could not be reached. Their retreat was an island in Loch

Earn and they allowed no boat on that water but their own. One of their

depredations went beyond endurance. They waylaid Macnab's messenger with

dainties for a Christmas feast. Macnab had twelve sons, the weakest of

whom could drive his dirk through a three-inch plank at one blow. One of

them was known ironically as Smooth John Macnab. On the night of the

robbery in question, the twelve were sitting gloomily around their

impoverished board when old Macnab came in.

"The night is the night,"

he said, looking significantly at his sons, "if the lads were the lads."

Without a word Smooth

John got up, followed by all his brothers, and left the castle. They

were gone the greater part of the night but the old chief waited, and at

last they came back. As they filed into the room Smooth John placed the

bearded head of the old Macnish chief on the table with the single

sentence, "The night is the night and the lads are the lads."

The twelve had carried

their own boat all the way over the mountains to Loch Earn and, making

their way to the Macnishes island, had found the robber clan in a

drunken sleep.

Only old Macnish was

awake; and when he heard a noise he called out, "Who is there?"

"Whom would you be most

afraid to see?" was the reply.

Macnish returned, "There

is no man I would like worse to see than Smooth John Macnab."

At that, Smooth John

drove in the door, and the old bandit had hardly time to shriek before

he met his end. Smooth John seized him by the gray hair and with one

sweep of his dirk cut off his head. Then they proceeded leisurely to

massacre the entire clan. There was no more robbing of the Macnabs.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, there was a Laird of Macnab

who had a high idea of his own feudal dignity. When he retired to his

Highland fastnesses without paying his accounts it was just as well not

to trouble him with reminders.

A messenger from the

Lowlands once coming with such a reminder to the Laird was entertained

lavishly at supper where no mention of his business was allowed. A

sumptuous apartment was given him for the night.

The next morning the

messenger was horrified to see a human body hanging from a tree outside

his window.

Asking fearfully what

that meant he was informed by a retainer of the Laird that it was "just

a puir messenger body that had the presumption to come wi4 a paper to

the Laird."

As can be gathered from

what has already been said, clan feuds were common. During the course of

a feud some of the Macdonells of Glengarry crossed the hills to Beauly

and were the means of originating some of the wild Highland music so

often bom amid savage scenes of human terror.

Coming suddenly upon a

congregation of Mackenzies at the kirk of Cill-a-Chriosd, they burnt

building and congregation together. While the fire was raging,

Glengarry's piper, to drown the shrieks of the victims, composed and

played the pibroch still known by the name of Cill-a-Chriosd.

On their way home,

triumphant, the Macdonells found themselves pursued and took to flight.

Their chief, closely followed by a gigantic Mackenzie, came over the

shoulder of the mountain at Beauly and making for the Resting Burn leapt

the yawning chasm at its narrowest part.. The avenger leapt also. He

missed his footing, fell back, and would have been killed but for a

branch of a tree on the edge which he grasped. Macdonell, returning to

the chasm, cut the branch with his knife and watched his enemy crash to

death in the abyss below.

The district of Tulloch

is the scene of the incident which inspired the wildest of the Highland

reels. A Macgregor had wooed, won and carried off Isobel, daughter of

the laird, in spite of her friends who favored a suitor of Clan

Robertson. The disappointed lover gathered a few followers* including

the young lady's brother, and came suddenly upon his successful rival.

Macgregor took refuge in a barn where with dirk and claymore and the

musket which his wife loaded for him he destroyed every one of his

assailants. So greatly was he overjoyed with his victory that on the

spot he composed and danced the 44 Reel o* Tul-loch,44 wildest of the

wild.

There is a tragic sequel

to the story. That day's prowess should have earned immunity for the

Highlander and his young bride but their enemies were inexorable. Isobel

was thrown into prison; and presently they barbarously showed her the

head of Macgregor who had been shot. At the sight of this bloody

memorial of the man she had loved she was struck with anguish and

expired.

One of the most

celebrated houses of Scotland is that of Douglas. Eight miles up the

Douglas Water is the village of Douglas near which is the site of

Douglas Castle. James Douglas became a page in the household of the

patriotic Bishop of St. Andrews. He joined Bruce. His complexion was

dark and his hair raven black, hence the sobriquet "Black Douglas." He

was of commanding stature, large limbed and broad shouldered, courteous

in manner but retiring in speech. He had a lisp like Hector of Troy.

Douglas Castle was the scene of many of his exploits. While Bruce lay

near-by, Douglas and two others went off to reconnoitre his old

property. In his absence an English garrison had taken possession of

Douglas Castle. A servant gathered a few retainers. The English garrison

were to attend church service and afterwards hold high carnival in the

castle.

Disguised as countrymen,

Black Douglas carrying a flail, the Scotsmen attended the service and

suddenly with the shout, "A Douglas! A Douglas!" they threw off their

countrymen's mantles and attacked the unsuspecting soldiers, all of whom

were killed or taken prisoners. Taking his captives with him Black

Douglas went to the castle and, after enjoying the feast prepared for

the English garrison, stove in the wine casks and killed the prisoners.

He then heaped up their bodies with the provisions, set fire to the mass

and burned down the castle. This episode has ever since been known as

the "Douglas Larder."

Douglas retired to

Galloway. He loved better "to hear the lark sing than the mouse squeak,"

he said. Clifford at once rebuilt the castle and put in one Thirlwall to

be governor. Douglas vowed to be-revenged. With a small following he

returned to Douglasdale and perpetrated a stratagem as old as warfare.

Setting an ambush in a place called Sandylands, he disguised some of his

men as herdsmen who drove a herd of cattle along the road in view of the

castle. Thirlwall determined to capture the cattle and issued out with

his garrison to seize them. When sufficiently far from the castle, the

party was surrounded by the ambushed Douglases and Thirlwall, and most

of his men were killed.

Black Douglas then gave

out that he had taken a vow to be revenged on any Englishman who should

dare to hold his father's castle. Douglas Castle was called the Perilous

Castle or the Adventurous Castle and it became a point of honor to hold

it.

A certain English lady

promised to marry an English knight if he would hold the Castle Perilous

for a year and a day. Black Douglas, learning that the castle was short

of provisions, disguised himself and his followers as country farmers

each of whom carried on his horse a great sack of grain or hay. The

garrison, seeing this cavalcade of traders apparently on the way to

market, determined to seize what they so much required and rode out in

pursuit, led by the knight. The disguised Scotsmen threw away their

loads and surrounded the Englishmen. The party was vanquished and the

English knight fell in the skirmish. In his pocket was found the letter

from his lady love. The knightly heart of Douglas was touched. This time

there was no after slaughter. The English survivors were honorably

treated and dismissed in safety to Carlisle. But Douglas Castle was

never again held by the English.

Clan Macdonald, one of

the most powerful in the Highlands, has a varied history. It was said by

the enemies of this powerful race that there were more cattle-lifters

among the Macdonalds than honest men in other clans. They received from

King Robert Bruce at Bannockburn the honor of a place on the right of

the army in battle. In that position they performed prodigies of valor.

They alleged that no engagement could be successful if this privilege

were overlooked, and they adduce the defeats of Harlaw and Culloden as

evidences.

The Macdonalds of

Clanranald were once attacked by the Frasers and Grants. The Macdonalds

retreated; the enemy, thinking they had dispersed, at once separated.

The Macdonalds came upon them singly and slew all but one man, although

only eight Macdonalds survived.

The weather was so warm

during this battle that the combatants stripped off their clothes and

the fight was called "The Battle of the Shirts."

The Macdonalds of the

Isles were so powerful that they were never in subjection to the

Scottish king and sometimes defeated the royal troops.

Donald Macdonald of the

Isles with ten thousand of his clansmen marched to within one day's

journey of Aberdeen and only the indecisive battle of Harlaw prevented

his subverting the monarchy itself.

During the reign of

William (III) occurred that hideous event known as the Massacre of

Glencoe. A monument now marks the spot. Glencoe is one of the wildest

and most beautiful glens in the Highlands of Scotland and was inhabited

by a branch of the great Clan Macdonald known as the Macdonalds of

Glencoe. Earl Campbell of Breadalbane was given by King William the duty

to receive the signs and bonds of submission of the clans and the money

to pay them upon their submission. He also received orders to proceed

with fire and sword against any refractory clans.

The Campbells and

Macdonalds of Glencoe were neighboring clans and the cattle of the

Macdonalds occasionally wandered onto the Campbell land and fed there.

In consequence, when Chief Alexander Macdonald of Glencoe came in to

render submission, Earl Campbell of Breadalbane proposed to Glencoe that

he, Campbell, should keep Glencoe's submission money in payment for the

alleged damage done to the Campbell lands by the wandering cattle.

Glencoe demurred, whereupon Campbell sent in word to the government that

the Macdonalds of Glencoe were not making submission and that they were

an incorrigibly lawless tribe of thieves and murderers.

The legal time for making

submission expired on January 1, 1692. On the previous day, December 31,

Glencoe appeared at Fort William and offered, a second time, to take the

oath of submission but Colonel Hill declined to receive it, giving him,

however, a letter to Sir Colin Campbell, at Inverary, in which he stated

the case and asked him to receive the oath even though the legal time

had expired. Sir Colin Campbell was sheriff of Argyllshire. Macdonald,

now thoroughly alarmed for the safety of his clansmen, started off at

once on his fifty-mile journey by wild mountain paths, across swollen

streams and through deep snow. So eager was he to reach Inverary at the

earliest possible moment that, although the road led close by his own

house, he would not pause an instant.

Arrived at last he found

Sir Colin absent and was obliged to wait three days of terror for his

kinsmen before Campbell returned. The sheriff read Colonel Hill's note

and agreed with the justice of it and consequently administered the oath

of submission. He also gave Macdonald a certificate stating that he had

rendered submission and wrote the Privy Council of the fact. Macdonald

accordingly felt secure; but the secretary of the Privy Council was a

creature who had a heart that would disgrace an ogre. This wretch

suppressed the letter to the Privy Council and made no record of the

submission. Ten days later an order bearing King William's signature was

issued. It was partly as follows: "As for Macdonald of Glencoe and that

tribe, if they can be distinguished from the rest of the Highlanders, it

will be proper for the vindication of public justice to extirpate that

set of thieves."

Accordingly, in the dead

of winter, Campbell of Glenlyon came with Argyll's regiment to

perpetrate the fiendish act. Macdonald met them and asked their errand

and they told him that they came for a friendly visit. Thereupon, with

Highland generosity, Macdonald opened his homes to the soldiers and for

weeks the murderers-to-be were quartered on their victims-to-be. On the

12th of February the order for the commencement of the butchery arrived.

With this order in his pocket, Glenlyon passed the evening of the 12th

playing cards with Macdonald's two sons and he and his officers accepted

an invitation to dine on the following day with Macdonald himself.

At 4 A. M. the slaughter

began. Macdonald was shot on his bed by one of the officers named

Lindsay who was to have dined with him that day. His wife was stripped

to the skin and died on the following day from horror and exposure. The

infernal wretch, Secretary Stair, had meanwhile issued his orders in

words that would befit the language of the imps of hell.

"In the winter," he

writes, "they cannot carry their wives and children and cattle to the

mountains. This is the proper season to maul them, in the long, dark

nights! "

Eighty victims were

massacred in cold blood but one hundred and fifty men, women and

children escaped. Secretary Stair, pursued by a never-relenting Nemesis,

committed suicide.

Fearing that the Campbell

regiment would return to finish the massacre of the remaining Macdonalds,

the survivors protected themselves in a manner which originated perhaps

the most famous and immortal piece of bagpipe music in all Scotland.

From its original bagpipe setting it has been put into a song none other

than "The Campbells Are Coming/* It was the custom in those times to

cause captured bagpipers to play for the benefit of their captors and

frequently when one clan went to attack another a bagpiper of the

assailed clan would be captured far from his native heath and be

compelled to play for the advance of the attacking party.

So the Macdonalds of

Glencoe who had survived the massacre made an agreement with their

bagpipers that if any of them were caught by the returning Campbells

they should play the piece invented at the time which would tell the

Macdonalds that the Campbells were coming. When the Campbells did return

to finish their horrid work given them to do by the English government

they captured a Macdonald bagpiper, and he, true to his oath to his

fellow-clansmen, lustily struck up "The Campbells Are Coming" and

continued to play the tune until near Glencoe when the alarmed clansmen

took flight. The Campbells never knew, till long after, the reason why

they found no Macdonalds in the glen of blood.

The most famous clan in

all Scotland, and the one which has had more parliamentary acts passed

about it than any other clan or combination of clans famous for its

misfortunes, and, as Sir Walter Scott says, "for the indomitable courage

with which they maintained themselves as a clan" after the British

parliament had determined upon their annihilation, and even the penalty

of death was pronounced against any person bearing the name is that of

Gregor or Macgregor.

Again the Minstrel of the

Border says of the Macgregors: "The energy and spirit which sustained

them in misfortune characterize them still." From their habitat the

Macgregors are called "The Children of the Mist."

The history of this clan,

descended from King Alpin and sometimes called Clan Alpin, is long and

striking. Its length is attested by the Scottish saying "Hills and

streams and Macalpins" putting back their origin to that of the hills

and streams.

"My race is royal" is

their proud boast. The Macgregors fought with their full force at

Bannockburn.

Living in the vicinity of

Loch Tay, a particularly sterile section of the always stubborn-soiled

Highlands, only with great difficulty did the Macgregors raise anything

to support themselves. Surrounded by powerful clans who hemmed them in,

their only recourse was to fight for a living and this made them the

greatest fighters in all Scotland.

When their bright red

tartans descended from the Glenarchy hills there were few who cared to

oppose them.

Time and again, century

after century, marauding bands of the Macgregors came down from their

mist enshrouded fastnesses and drove home the cattle of the neighboring

clans.

Owing to a desire for the

lands of the hemmed-in Macgregors and also desirous of breaking the

power of so virile a clan, the neighbors of the Macgregors plotted their

destruction. Persecutions they brought them but downfall never.

They were attacked on all

sides. The sanguinary batde of Glenfruin was forced upon the Macgregors.

Sir Humphrey Col-quhoun undertook to coerce the Macgregors with

unsatisfactory results. Alastair Macgregor of Glenstrae, their chief,

went to Luss, Colquhoun's territory, with only two hundred Macgregors

for an amicable setde-ment of the trouble.

The interview was

satisfactory to all appearances and the two hundred Macgregors started

homewards. But Colquhoun treacherously determined to take advantage of

them. Collecting some Buchanans, Graemes and others to the number of

five hundred horsemen and three hundred foot they waylaid the two

hundred homeward-bound Macgregors in the vale of Glenfruin. where there

was no road, and immediately attacked them without any provocation.

It would seem reasonable

to state that such a piece of consummate treachery has rarely been

equalled, but the outcome was not as the perpetrators planned. Many

years later there lived a ploughman poet of Scotland who wisely wrote:

"But, Mousie, thou art no

thy lane

In proving foresight may be vain;

The best laid schemes o' mice an' men

Gang aft a-gley,

And lea'e us nought but grief an' pain

For promis'd joy."

The God of battles

defended the innocent in that bloody transaction and, incredible as it

may seem, the eight hundred enemies of the two hundred Macgregors only

succeeded in killing two Macgregors. Fired by righteous wrath and their

indomitable spirit the Macgregors pressed the uneven fight till there

was hardly a survivor of their enemy.

The district on the west

shore of Loch Lomond is associated with some savage passages in the clan

wars of the Highlands. There, at Bannachra Castle the Macgregors and

Macfarlanes besieged and killed Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss in 1592.

Subsequently the

Macgregors and Macfarlanes themselves got into difficulties and the

Macgregors straightened the matter out by completely annihilating the

Macfarlanes who were responsible. About ten years later, the Macgregors

killed a royal deer-keeper named Drummond and, asking at his sister's

house for food, they placed the murdered man's head on the table with

the mouth stuffed with bread and cheese, where she could see it on

entering the room. Other acts of savagery following quickly upon this, a

strong effort to break the strength of the Macgregors was determined

upon.

More than a hundred

widows of the members of Clan Colquhoun who had been killed at Glenfruin

by the Macgregors rode through the streets of Stirling, each one dressed

in weeds, mounted upon a white palfry and bearing aloft upon a spear her

husband's blood-stained shirt. Many women waved also the shirts of other

men, and the total was more than two hundred. The aim of this

demonstration was to arouse the government of James VI to take measures

against the Macgregors. James was easy of persuasion, and accordingly,

within a month, the name of Macgregor was abolished by Act of Privy

Council and it was decreed that anyone calling himself Gregor or

Macgregor must take another surname under pain of death.

More than one hundred

years later, David Balfour, hero of Stevenson's novel of that name, met

a lassie of apparent note in the streets of Edinburgh and she befriended

him. She learned that he had come from Balquhidder. He, being moved by a

spirit of gratitude for what she had done for him, said, "I wish that

you would keep my name in mind for the sake of Balquhidder; and I will

yours for the sake of my lucky day."

"My name is not spoken,"

she replied, with a great deal of haughtiness. "More than a hundred

years it has not gone upon men's tongues, save for a blink. I am

nameless like the fairies. Catriona Drummond is the one I use."

"Now," said Balfour, "I

knew where I was standing. In all broad Scotland there was but the one

name proscribed, and that was the name of the Macgregors."

All the Macgregors

connected in any way with the battle at Glenfruin were prohibited from

carrying any weapon other than a pointless knife wherewith to cut up

food. In 1613 this Act was repeated and again four years later and

members of the Clan were forbidden to assemble in numbers exceeding

four. Within a year thereafter Allaster Macgregor of Glenstrae, who had

commanded at Glenfruin, and about thirty-five of the clan had been taken

and hanged. With the Restoration in the reign of Charles II and James II

the Acts against the Clan Macgregor were repealed, but they were

re-enacted during the Revolution.

To these Acts of

oppression the Macgregors responded with unabated fortitude. Their lands

were taken from them by the king and given to powerful neighbors who had

really been the instigators of the oppressions of the Macgregors for the

sake of obtaining their lands. These grantees came to take the lands by

virtue of their parchment rolls and found a battle line of the

Macgregors awaiting to defend their hereditary tide with the naked

claymore. The attitude of the Macgregors is best expressed in the wild

gathering song of the Clan:

"The moon's on the lake,

and the mist's on the brae,

And the clan has a name that is nameless by day.

Our signal for fight, which from monarchs we drew,

Must be heard but by night in our vengeful haloo.

Then haloo, haloo, haloo, Gregalach.

If they rob us of name and pursue us with beagles,

Give their roofs to the flame, and their flesh to the eagles.

Then gather, gather, gather gather, gather, gather.

While there's leaves in

the forest or foam on the river,

Macgregor, despite them, shall flourish forever.

Glenorchy's proud mountain, Colchurn and her towers,

Glenstrae and Glenlyon, no longer are ours;

We're landless, landless, landless, Gregalach,

Landless, landless, landless.

Through the depths of Loch Katrine the steed shall career,

O'er the peak of Ben Lomond the galley shall steer.

And the rocks of Craig

Royston like icicles melt,

Ere our wrongs be forgot or our vengeance unfelt.

Then haloo, haloo, haloo, Gregalach.

If they rob us of name and pursue us with beagles,

Give their roofs to the flame, and their flesh to the eagles.

Then gather, gather, gather, gather, gather, gather,

While there's leaves in the forest, and foam on the river,

Macgregor, despite them, shall flourish forever."

So unmerited were the

wrongs of the Macgregors, so bravely were they borne for two hundred

years, that to this day it is often the custom for clan gatherings to

rise from the food-laden board, lift their glasses and drink heartily to

the toast "Clan Macgregor!"

Finally, about one

hundred years ago, by Act of the British Parliament, the penal statutes

against the Macgregors were forever abolished.

It was during the period

when the use of the name Macgregor was prohibited that the most famous

member of the clan flourished.

Robert Campbell

Macgregor, commonly called Rob Roy or Robert the Red, was brought up on

a farm in Balquhidder near the head of Loch Earn, previously mentioned

in connection with the adventure of Smooth John Macnab and his eleven

brothers. He was born about the year 1671. His mother was a Campbell

and, as Macgregor was proscribed, with repugnance he assumed his

mother's name.

Previous to the year 1712

he was occupied in a perfectly legitimate manner as a thriving cattle

trader with the Lowlanders of the Scottish Borders and he had the

confidence and protection of the Duke of Montrose. A series of

unfortunate ventures, however, put an end to this period of prosperity,

and Rob Roy found himself indebted in large sums to Montrose and others.

Proceedings were taken against him in the course of which his wife and

children were evicted from their home in midwinter. Deprived of the

ordinary means of livelihood, hunted, anathematized, he began the period

of oudawry with which his name is associated. Proscribed and shut out

from every lawful calling, Rob Roy, who conceived the action of Montrose

as unjust and tyrannical, attached himself to the rival house of Argyll,

whose name he had assumed.

With a band of

disaffected persons belonging mainly to his own clan, Rob Roy set up as

a freebooter and protector of weaker property rights for a stipulated

price.

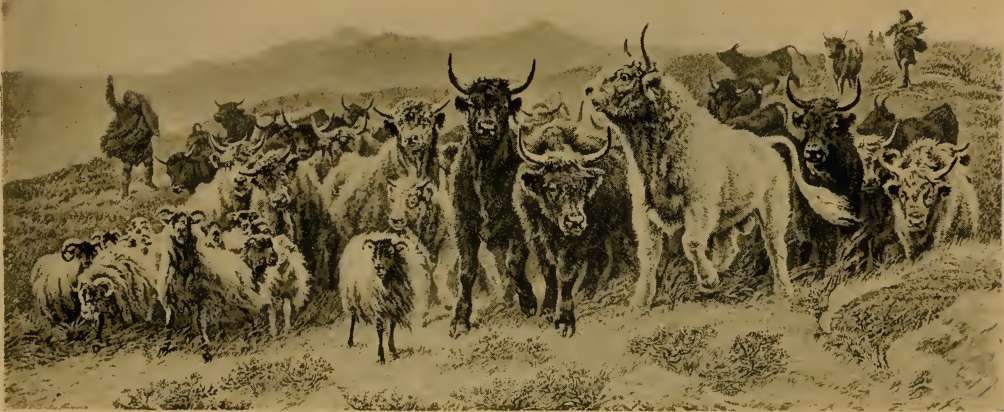

The Stampede

"His stature," writes Sir

Walter Scott, "was not of the tallest, but his person was uncommonly

strong and compact. The greatest peculiarities of his person were the

breadth of his shoulders and the great and almost disproportioned length

of his arms, so remarkable indeed that it was said that he could,

without stooping, tie the garters of his Highland hose, which are placed

two inches below the knee. His countenance was open, manly, stern at

periods of danger, but frank and cheerful in his hours of festivity. His

hair was dark red, thick and frizzled and curled short around the face.

Though a descendant of the bloodthirsty Ciar Mohr, he inherited none of

his ancestor's ferocity. On the contrary Rob Roy avoided every

appearance of cruelty, and it is not averred that he was ever the means

of unnecessary bloodshed or the actor in any deed which could lead the

way to it. Like Robin Hood of England he was a kind and gentle robber,

and while he took from the rich, was liberal in relieving the poor."

His lawless life went on

from year to year until the English government put a price upon his

head. When this became known to Rob Roy he assembled his clansmen, armed

them fully and marched down into a Lowland city. When arrived, he and

his retainers passed through the streets of the city and waited for

someone to attempt his capture but no hostile hand was raised.

Finally the government

sent a regiment into Rob's territory to capture him. Wolfe, of Quebec

fame, was an officer in that regiment. When the English had arrived

unopposed in Rob's vicinity Rob Roy himself walked into their camp and

said to an officer, "You seek Rob Roy Macgregor. Here I am." Even then

they dared not touch him for they knew his clansmen were behind every

rock.

An earthwork was thrown

up by the English and Rob sent in word that he would wait until they

finished it before he captured it. When the fort was completed Rob and

his clansmen stormed it and it fell. The prisoners were sent to the

Lowlands with a note from Rob Roy asking the government to send men, not

women, to capture Rob Roy Macgregor.

Sir Walter Scott gives

the following tradition regarding the manner of Rob Roy's death. When

very near his end, a certain Maclaren, who had been an enemy, came to

see him.

"Raise me from my bed,"

said Rob; "throw my plaid around me and bring me my claymore, dirk and

pistols. It shall never be said that a foeman saw Rob Roy Macgregor

defenseless and unarmed."

Rob Roy maintained a

cold, haughty civility during the short conference, and as soon as

Maclaren had left the house he said, "Now, all is over; let the piper

play. We Return No More," and he is said to have expired before the

dirge was finished. He was buried in the kirkyard of Balquhidder where

his tombstone is only distinguished by a rude attempt at a figure of a

broadsword.

At the time of the story

of Stevenson's "Kidnapped," its hero says upon coming to Balquhidder:

"In the braes of Balquhidder were many of that old, proscribed,

nameless, red-handed clan of the Macgregors, Their chief, Macgregor of

Macgregor, was in exile; James More, Rob Roy's eldest son, lay waiting

his trial in Edinburgh Castle; they were in ill blood with Highlander

and Lowlander. Robin Oig, another of Rob Roy's sons, stepped about

Balquhidder like a gentleman in his own walled garden. It was he who had

shot James Maclaren, the clansman who had visited his dying father, yet

he walked into the house of his blood enemies as a commercial traveller

into a public inn. The corrie is still pointed out on Cruachan where the

last Macgregor of the neighborhood to be hunted with a bloodhound like a

wild beast, turned to bay and shot his deep mouthed tracker. The Earl of

Murray transplanted three hundred of the proscribed Macgregors from Men-teith,

and setded them as a barrier against another turbulent clan, the

Mackintoshes, in Aberdeenshire. There, under the name of Gregory, these

descendants of the Clan Alpin gave birth not only to some, but to a

whole galaxy of the most distinguished men that Scodand has produced. In

the church, in the army, in the civil professions, Macgregor has long

been, and is now, a familiar and an honored name."

But to other themes! The

spirit of Mary Stuart hung heavy over the hills of her own bonnie

Scotland. Her untimely death by treachery was not forgotten and the

mutterings to her and to her race in the breasts of the Scots from time

to time grew audible.

On a November day in 1715

there occurred the ill-managed battle of Sheriffmuir on the moor above

Dunblane where the sheriff's weapons chawings were held in old times.

This battle put an end to the first Jacobite rebellion.

The circumstances of the

fight are well known. The Earl of Mar was marching from Perth to

surprise Argyll, the royalist general, who lay in Stirling. Argyll

marched to meet the enemy with a force of only three thousand five

hundred while that of Mar was nine thousand strong. On the night of the

13th, the Highland army, ever true to the Stuarts, came into view around

the shoulder of the Ochils; and the ancient Gathering Stone on the moor

is pointed out as the place where the Highlanders sharpened their

claymores and dirks. The right wings of both armies began the battle and

both right wings were victorious but no further fighting was done and

the armies gradually drew away from each other, leaving one thousand

dead on the field. The battle cannot fairly be regarded as a loss to

either side, and the following rhyme contains a true account of it.

"Some say that we wan,

Some say that they wan,

And some say that nane wan at a', man;

But o' a'e thing I'm sure

That at Sheriffmuir

A battle there was that I saw, man;

And we ran, and they ran,

And they ran, and we ran,

And we ran and they ran awa' man."

Rob Roy Macgregor stood

aloof and watched the proceedings with five hundred Macgregors. When

appealed to by Mar to take part in the action, Rob refused, saying, "No,

no, if it cannot be done without me it cannot be done with me." The

century was not to complete its cycle before these Macgregors were to

cover themselves with immortal glory at the battle of Culloden.

Before that century had

elapsed a period had arrived in Scottish history which has not a

parallel extant a period marked by fortitude, devotion and

self-sacrifice which it may be possible to say has not an equal in

history. It is known in Scotland as "The '45," referring to the year

1745. Around that date cluster more romance and song than around any

other.

Inverness-shire is more

closely associated with the Jacobite rising known as "The '45" than any

other county in Scotland. It was on the island of Eriska that Prince

Charles Edward first set foot on Scottish soil; at Highbridge occurred

the first outbreak of hostilities; at Glenfinnan the standard was

raised; at Invergarry the chiefs signed a bond to stand or fall

together; on Culloden Muir was fought the closing and decisive battle of

the campaign; and, finally, it was the wild mountainous region of

western Inverness-shire, and the desolate islands of the western

Hebrides that received and concealed the Prince during those five

months' wanderings which constitute the most romantic episode in the

history, one might almost say of any country, but most certainly of

Scotland.

Charles Edward Lewis

Casimir was the elder son of James (son of James VII) sometimes called

the Pretender and sometimes the Chevalier de St. George.

His mother was Clementina,

granddaughter of John Sobieski, King of Poland. He was born at Rome on

December 20, 1720, and thus was but twenty-four years old when,

despairing of obtaining that aid from France which had all along been

deemed necessary for the attempt to place his father on the British

thronethen in the possession of his second cousin and her husbandhe

determined to try what daring and his own winning personality could

accomplish.

On June 22, 1745, Prince

Charlie, attended by only seven adherents, embarked at Nantes on board

La T)outelle and twelve days later he was joined by the Elizabeth, a

French ship of war privately fitted out. During the voyage the Elizabeth

attacked a British man-of-war and received such injuries as compelled

her to put back to France. La Doutelle proceeded alone, and on July 23,

a month from the date of embarkation, Prince Charlie landed on the bleak

little island of Eriska, in the Outer Hebrides, and spent his first

night in what he looked upon as his father's rightful kingdom, in the

cottage of a tenant of the Macdonalds of Clanranald.

As that little ship

approached the wild Scottish coast and the Prince gazed on the land of

his royal fathers, wondering what the outcome of his righteous effort

would be, a large Hebridean eagle came and hovered over the vessel. It

was first observed by the

Marquis of Tullibardine,

who did not choose to make any remark upon it at once lest he be deemed

superstitious.

Some hours later, on

returning to the deck after dinner and seeing the eagle still following

their course, the Marquis pointed it out to the Prince, saying, " Sir,

this is a happy omen: the king of birds is come to welcome your royal

highness on your arrival in Scotland."

It would have seemed so

on that memorable day, months later, in Edinburgh when, on the eve of

the Battle of Prestonpans, in the presence of Prince Charles Edward,

James, his exiled father, was proclaimed James VIII, King of Great

Britain and Ireland. That was the occasion of the most ardent enthusiasm

Edinburgh has displayed in all its centuries of existence.

As the Prince rode up the

street dressed in the Highland garb of the royal Stuarts with his own

additional markings, ladies pressed to touch his stirrup and kiss his

hand, rank and beauty crowded the balconies and forestairs, and scarfs,

kerchiefs and banners waved.

As the heralds, in their

antique dress, with blast of trumpet proclaimed the king, the loveliest

of the Jacobite ladies rode through the throng distributing the white

cockade. Wild with delight, at the ball in Holyrood, to see the heir of

the Scottish kings appear once more in the palace of his fathers, the

bravest blood of all Scotland that night crowded the halls.

The daughters of lord and

chief cast J on the Prince looks of undisguised devotion. Never had so

gallant a prince appealed to his subjects in such romantic

circumstances, and never did a people receive their sovereign with so

much rapture.

Here on the following day

he received a bitter disappointment. Alexander Macdonald of Boisdale,

brother of Clanranald, chief of an important branch of the Clan

Macdonald, came to assure the Prince of the hopelessness of the

expedition. Without men, arms and money, he declared, nothing could be

done, nor could the clam be counted upon to rise.

He ended by begging the

Prince to return home, to which the latter made reply, "I am come home,

sir, and can entertain no notion of returning to the place whence I

came. I am persuaded that my faithful Highlanders will stand by me."

Well indeed did the

bonnie Prince know the temper of Highland blood! Boisdale left him

persisting in his refusal to influence his brother to call out his clan.

While the entire party

were still on board La Doutelle and when as yet the foot of Prince

Charles Edward had not been placed on Scottish soil, in spite of the

protestations of Clanranald and others Charles persisted and implored.

During the conversation

the parties were gesticulating on the deck near where a Highlander stood

armed at all points, as was then the custom. He was a younger brother of

Kinlochmoidart and had come off to enquire for news, not knowing who was

on board.

When he gathered from the

discourse that the stranger was the heir of Britain, when he heard his

chief and brothers refuse to take up arms for their Prince, his color

went and came, his eyes sparkled, he shifted his place and grasped his

claymore.

Charles observed his

demeanor, and turning suddenly round, appealed to him: " Will you not

assist me?

"I will! I will!"

exclaimed Ranald. "Though not another man in the Highlands should draw a

sword, I am ready to die for you!"

The tears of gratitude

came into the eyes of the Prince and the thanks to his lips.

The Prince proceeded to

the mainland, landing at Borradale in the country of Clanranald. Young

Clanranald visited the Prince on the ship and heartily embraced his

cause. At Borradale most disheartening news was received from Macleod of

Macleod and Sir Alexander Macdonald of Sleat. The two Skye chiefs

mentioned, upon whose adherence the Prince had confidently relied, not

only refused to join in the expedition but actually gave active aid to

the government. So desperate was the outlook at this juncture that all

those about the Prince joined in endeavoring to persuade him to abandon

the attempt and return to France.

What king has ever shown

better spirit than the Prince in his reply that, if he could find but

six men willing to follow him, he would choose rather to skulk among the

mountains of Scotland than to turn back. In all history what royal scion

has uttered braver words or ones more worthy of laudation.

Lochiel, chief of Clan

Cameron, came to Borradale bent upon persuading the Prince from making

the attempt but the result of the interview was his own promise to join.

Prince Charlie reproachfully announced his purpose to raise the royal

standard with the few friends he had.

"Lochiel," he declared,

"who my father has often told me was our firmest friend, may stay at

home and learn from a distance the fate of his Prince."

Lochiel replied that not

he alone but "every man over whom nature or fortune" had given him power

should share the Prince's fate. Macdonald of Glengarry promised to send

out his clan.

Thus it was decided to

raise the standard of James VIII at Glenfinnan, and messengers were sent

throughout the country calling upon all who favored the cause to meet

the Prince there. At about this time two companies of Royal Scots, a

regiment of regulars, were taken prisoners by a hastily assembled body

of Highlanders on the shores of the now Caledonian Canal.

The Royal Scots were

marching along when the dreaded sound of the bagpipes broke upon their

unaccustomed Lowland ears and they were terror-stricken to see their way

blocked by what appeared to be a considerable body of Highlanders. The

object of their alarm was ten or twelve Macdonalds who, by skipping and

leaping about and by holding out their tartans between each other,

contrived to make a formidable appearance. The outcome was the capture

of the two hundred Lowlanders by the dozen Highlanders.

On August 19 the Prince

reached Glenfinnan, but to his great disappointment none of the clans

had assembled. Only about two hundred of Clanranald's men were present

and the actual raising of the standard was intrusted to the Marquis of

Tullibardine who was in such feeble health that two Highlanders had to

support him to the top of a small elevation, now marked by a monumental

tower, selected for the ceremony of raising the standard of Bonnie

Prince Charlie, relative of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Tullibardine then flung

upon the mountain winds that flag which, shooting like a streamer from

the north, was soon to spread such woe and terror over the peaceful

vales of Britain. A declaration in the name of James VIII to the people

of Great Britain, a commission appointing the Prince to be regent in

place of his absent father, and a manifesto by the Prince were then

read. The loyal clans poured in. A few days later intelligence was

received of the steps the government was taking to suppress the rising.

A reward of $150,000 had

been offered for the Prince who retaliated by offering the same amount

for the apprehension of the so-called Elector of Hanover. Word was also

brought that General Cope, for the government, was marching toward the

mountain pass of Corryarick, about ten miles south of Fort Augustus.

A detachment was sent

forward to seize the pass and the rest of the army followed the next

day. After crossing the Corryarick Pass the Highlanders, now augmented

by various bodies of recruits, found that General Cope had turned aside

to march to Inverness, thus avoiding the battle which the Highlanders

were longing to give. Had the decisive battle been fought then instead

of under the circumstances of semi-starvation and frightful odds of

Culloden, the result would have been vastly different to British

history.

"Cam' ye by Athol, lad

with the philabeg,

Doun by the Tummel or the banks of the Garry?

Saw ye the lads with their bonnets and white cockades

Leaving their mountains to follow Prince Charlie?

"Follow thee, follow thee,

wha wadna follow thee?

Lang thou hast loved and trusted us fairly,

Charlie, Charlie, wha wadna follow thee?

King o' the Highland hearts, Bonnie Prince Charlie!"

Ravages by night and day,

bribes of unheard-of size, destructions of homes and families, hunger,

thirst, nakedness, peril and sword endured for Charlie's sake,

subsequently proved beyond a peradventure the kingship of Bonnie Prince

Charlie over Highland hearts.

As General Cope had too

much the start of the Highlanders for pursuit it was determined to turn

as once to the Lowlands with a view to the capture of Edinburgh. From

the pass of Corryarick a detachment was sent to make an attempt to

capture the government barracks of Badenoch. They brought back an

important captive Ewan Macpherson of Cluny, captured at Cluny Castle.

Macpherson had left Sir John Cope only the day before to raise his clan

for the government. But he had been contemptuously treated by Cope who,

with extraordinary fatuity, could not see the difference between a

captain of the line and a Highland chief, whose word was law to a whole

clan and who could command the unquestioned service of four hundred

claymores. He was furious at Cope and the persuasions of his Jacobite

friends so acted on him that, after ten days' imprisonment in the

Jacobite camp, he again returned home to raise his clan but now for

Prince Charlie whom he afterwards joined and served to the end. Leaving

Perth, the Highland army marched to Dunblane and to Edinburgh. Then came

the victorious battle of Prestonpans which gave them Edinburgh.

Charles, while in

Edinburgh, learned that General Cope had landed at Dunbar and was at

last marching to give him battle which he had previously avoided.

The brave Prince proposed

to meet him half way and asked the Highland chiefs how the clansmen

would behave toward a general who had already avoided them. The reply

was from Keppoch who was the only one who had seen the Highlanders in

action against regular troops. He said "Your Highness will be pleased

with their conduct."

The Prince, putting

himself at the head of the Highlanders, presented his claymore and spoke

aloud, "My friends, I have thrown away the scabbard! "

When the royal troops

first perceived the army of the Prince they raised a shout, to which the

Highlanders readily replied. As evening drew on, after the cannon had

been ineffectually playing on the Highland ranks, the Scotsmen wrapped

themselves in their tartans and lay down to sleep on the stubble fields.

Prince Charlie slept thus with his true-hearted men.

Oh, that fateful night!

The Southron forces little knew the mettle of the kilted men so near

them. What would the morrow disclose? Who would be first to fall, and

how many would never return to England? But, on the other hand, would

there be a battle? Would not those wild Highlanders be awed by the great

military display before them, and retreat? In the English hearts there

was something which told them that they would not.

At length the first

intimations of approaching day came but the mists of Scotland hung heavy

over the field. In the English camp not a sound could be heard in the

Scottish army. Why that awe-inspiring silence? The sentries peered

fearfully through the fog.

All at once there was a

universal start of fright on the Southron picket line. Here and there in

the clouds of vapor could be seen bodies of men rushing forward in

absolute silence! On this side were men in red tartans, on that in blue;

here was green, and there, yellow. As soundless as the interweavings of

the mist was their running approach!

Nothing is more

terrifying than an enemy in the dark especially when you know that he is

approaching without sound. The English were terror-stricken. They did

not know the efficient method of fighting employed by Scotia's Gaelic

sons.

This method caused them

to advance with the utmost rapidity toward the enemy, give fire only

when in actual musket length of the human object of the attack, and

then, throwing down their firearms, draw their claymores and holding a

dirk in the left hand along with the target on the left arm dart with

fury on the enemy through the smoke of their fire.

When within reach of the

enemy's bayonets, bending their left knee, they contrived to receive the

thrust on their targets; then raising their left arm and with it the

enemy's bayonet point, they rushed in upon the soldier, now defenseless,

killed him at one blow, and were in a moment within the lines, pushing

right and left with sword and dagger, often bringing down two men at

once. These tactics won the battle of Prestonpans in just four minutes.

All that followed was carnage.

There is a stirring

picture of the advance of the Highlanders at Prestonpans which is an

inspiration to all who see it. Advancing up the hill, and therefore at a

disadvantage, is the braw double line of laddies from the mountains;

Prince Charlie leads the second line. On each face is pictured a

self-sacrificing purpose willing to forfeit life itself to maintain;

each strong right hand clasps the unconquered claymore of Scodand and

each left arm is bent behind its javelin pointed targe; victory is

spelled on their faces.

The wounded of the royal

army were treated by their conquerers with a degree of humanity which

might well have been imitated by the English on a subsequent occasion.

Immediately after

Prestonpans came the advance of the Highland army into England itself

and

"England shall many a day

tell of the bloody fray,

When all the blue bonnets came over the Border."

There were many in

Lancashire and Wales ready to join the standard of the Stuart king. The

army had then increased to six thousand men who had left homes and

families and now native country simply to fight for the right and

justice. In all that went before this and all that comes after, it

should be remembered that these devoted men were well aware that no

advantage would accrue to themselves from all that they did or were

going to do. They were animated by pure love and desire to see filial

devotion prevail in the royal as well as in their own families.

Terror unmitigated spread

throughout England, especially in the counties immediately subject to

the Highlanders approach. No one had ever seen any large body of

Highlanders and few knew anything about them. It was commonly reported

that they were pagan savages, cut-throats and des-poilers of all

despoilable.

Contrary to expectation

and greatly to the surprise of the English, the Highlanders neither

attempted to cut the throats nor violate the property of the

inhabitants. Carlisle, England, was captured. It is credibly stated that

women hid their children at the Highlanders approach under the

impression that they were cannibals, fond in particular of the flesh of

infants.

Everywhere there was

great surprise that these men, so far from acting like savage robbers,

expressed a polite gratitude for what refreshments were given them.

The great city of

Manchester was entered and recruits obtained. On the first of December,

1745, the army left Manchester with London as their object. On the 4th