|

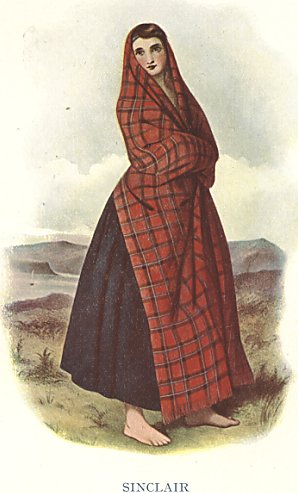

The name Sinclair is of

Norman origin from "Saint-Clair-sur-Elle" and was established in Scotland in

1162 when Henry de St Clair of Roslin was granted lands in Lothian. His descendant Sir

William became guardian to the heir of Alexander III and gained the Barony of Rosslyn in

1280. His son, Sir Henry fought with Bruce at Bannockburn and was one of the Scottish

barons who signed the letter to the Pope asserting Scottish independence. His son, Henry

married Isobel, co-heiress of the Earldom of Orkney and Caithness and thus transported the

Sinclairs to the far north of Scotland. Their son, Henry Sinclair of Roslin became Earl of

Orkney in 1379, obtained from King Haco VI of Norway. In 1455 William, 3rd Sinclair Earl

of Orkney was granted the Earldom of Caithness. He also founded the celebrated Rosslyn

Chapel in 1446. In 1470 the Earl of Orkney and Caithness was compelled to resign Orkney to

James III in exchange for the Castle of Ravenscraig in Fife. The King was jealous of the

semi-royal chief of the Earldom of Orkney which had been inherited by the Sinclairs from

the Norse Sea-Kings. The Earls of Caithness were engaged in a long succession of feuds

with the Sutherlands, the Gunns and the Murrays, often giving rise to violent deaths. The

2nd Earl, William died at Flodden and the 3rd Earl in a Sinclair Civil War in the Orkneys.

The direct line came to an end with George, 6th Earl who through debt granted the title

and estates to Sir John Campbell of Glenorchy. In 1676, after Sir John assumed the title,

George Sinclair of Keiss disputed the claim and seized the Caithness estates, only to be

defeated in 1680 by the Campbells near Wick. Although the claim was lost by the sword, the

Privy Council rendered his claim in 1681 and he became the 7th Earl of Caithness. At the

time of the '45 the northern Sinclairs were ready to join Prince Charles Edward however

after Culloden they disbanded quietly. The Earldom has since passed through many Sinclair

families and up until 1986 a Sinclair Earl of Caithness owned the long-ruined stronghold,

Castle Girnigo, and the Sinclairs of Ulbster still hold vast estates in Caithness. Septs

and dependants of the Sinclairs include Caird, Clouston, Clyne, Linklater and Mason.

Another Account of the Clan

BADGE: Conasg (Ulex Europaeus) furze or

whin.

PIBROCH: Spaidsearachd

Mhic nan Ceàrda.

EVERY

Scottish schoolboy is familiar with the story of the heroic fight with the

Moors on a field of Spain in which the Good Lord James of Douglas met his

death. In that fight, it will be remembered, Douglas noted that a Scottish

knight, Sir William St. Clair, had charged too far, and had been

surrounded, by the enemy. "Yonder worthy knight will be slain,"

he exclaimed, "unless he have instant help," and he galloped to

the rescue. Then, himself surrounded by the enemy, and seeing no hope for

escape, he took from his neck the casket containing Bruce’s heart, and

threw it forward among the enemy. EVERY

Scottish schoolboy is familiar with the story of the heroic fight with the

Moors on a field of Spain in which the Good Lord James of Douglas met his

death. In that fight, it will be remembered, Douglas noted that a Scottish

knight, Sir William St. Clair, had charged too far, and had been

surrounded, by the enemy. "Yonder worthy knight will be slain,"

he exclaimed, "unless he have instant help," and he galloped to

the rescue. Then, himself surrounded by the enemy, and seeing no hope for

escape, he took from his neck the casket containing Bruce’s heart, and

threw it forward among the enemy.

Pass first in fight,"

he cried, "as thou were wont to do; Douglas will follow thee or die!

" and pressing forward to the place where it had fallen, was himself

slain. The William St. Clair who thus comes into historical note, and who,

with his brother John, was slain on that Andalusian battlefield, was the

ancestor in direct male line of the Sinclairs, Earls of Caithness, of the

present day.

Like so many of the great

Highland families, the St. Clairs were not originally of Celtic stock.

Their progenitor is said to have been William, son of the Comte de St.

Clair, a relative of William the Conqueror, who "came over" with

that personage in 1066. He or a descendant seems to have been one of the

Norman knights brought into Scotland to support the new dynasty and feudal

system of Malcolm Canmore and his sons. In the twelfth century there were

two families of the name, the St. Clairs of Roslyn and the St. Clairs of

Herdmonstoun respectively, though no relationship was traced between them.

Sir William de St. Clair of Roslyn, who flourished in the latter half of

the thirteenth century, was a guardian of the young Scottish king,

Alexander III., and one of the envoys sent to negotiate the French

marriage for that prince. He was sheriff of Dumfries and justiciar of

Galloway, and, as a partizan of Baliol, was captured by the English at

Dunbar in 1294, escaping from Gloucester Castle nine years later. His son,

Sir Henry, was also captured at Dunbar, but exchanged in 1299. He was

sheriff of Lanark in 1305, fought for Bruce at Bannockburn, and received a

pension in 1328. It was his brother William, Bishop of Dunkeld, who

repulsed the English at Donibristle in 1317 and crowned Edward Baliol in

1332.

Sir William St. Clair who

fell in Spain in 1329 was the elder son of Sir Henry St. Clair of Roslyn.

His son, another Sir William, who succeeded to the Roslyn heritage, added

immensely to the fortunes of his family by marrying Isabella, daughter and

co-heir of Malise, Earl of Strathearn, Caithness, and Orkney. In

consequence his son Henry became Earl or Prince of Orkney at the hand of

Hakon VI. in 1379. He conquered the Faroe Islands in 1391, wrested

Shetland from Malise Sperra, and with Antonio Zeno, crossed the Atlantic,

and explored Greenland. His son, another Henry Sinclair, second Earl of

Orkney, was twice captured by the English, at Homildon Hill in 1402 and

with the young James I. on his voyage to France in 1406. He married

Isabella, daughter and heiress of Sir William Douglas of Nithsdale, and

the Princess Egidia, daughter of Robert II.; and his son, William, third

Earl of Orkney, was one of the most powerful nobles in the country in the

time of James II.

The Earl was one of the

hostages for the ransom of James I. in 1421, and in 1436, as High Admiral

of Scotland, conveyed James’s daughter to her marriage with the Dauphin,

afterwards Louis XI. of France. At his investiture with the earldom of

Orkney in 1434 he acknowledged the Norwegian jurisdiction over the

islands, and in 1446 he was summoned to Norway as a vassal. In this same

year he began the foundation of the famous Collegiate Church, now known as

Roslyn Chapel, on the Esk near Edinburgh, which is perhaps at the present

hour the richest fragment of architecture in Scotland, and in the vaults

of which lie in their leaden coffins so many generations of "the

lordly line of high St. Clair." Sir Walter Scott has recorded in a

well-known poem the tradition that on the death of the chief of that great

race Roslyn Chapel is seen as if it were flaming to heaven. At his great

stronghold of Roslyn Castle at hand the Earl of Orkney lived in almost

regal splendour. In 1448, when the English, instigated by Richard, Duke of

York, broke across the Borders and burned Dumfries and Dunbar, the Earl

assisted in their repulse and overthrow. In the following year he was

summoned to Parliament as Lord Sinclair. From 1454 to 1456 he was

Chancellor of Scotland under James V., whose side he took actively against

the Earl of Douglas, though Douglas’s mother, Lady Beatrice Sinclair,

was his own aunt, and who, in 1455, on his relinquishing his claim

to Nithsdale, made him Earl of Caithness. This honour was no doubt partly

due to the fact that, through his great-grandmother, the wife of Malise of

Strathearn, he inherited the blood of the more ancient Earls of Caithness,

the first recorded of whom is said to be a certain Dungald who flourished

in 875. A few years later

certain actions of Earl William and his son may be said to have brought

about the marriage of James III. and the transference of Orkney and

Shetland to the Scottish crown. During some disagreement with Tulloch,

Bishop of Orkney, St. Clair’s son seized and imprisoned that prelate.

Forthwith Christiern, King of Denmark, to whom Orkney then belonged, wrote

to the young Scottish king demanding not only the liberation of his

bishop, but also the arrears of the old "Annual of Norway" which

Alexander III. of Scotland had agreed to pay for possession of the

Hebrides. The matter was settled by the marriage of James III. to

Christiern’s daughter, Margaret, the annual of Norway being forgiven as

part of the princess’s dowry, and the Orkney and Shetland islands

pledged to James for payment of the rest. St. Clair was then, in 1471,

induced to relinquish to the king his Norwegian earldom of Orkney,

receiving as compensation the rich lands of Dysart, with the stronghold of

Ravenscraig, which James II. had built for his queen on the coast of Fife.

The earl was twice married.

By his first wife, Elizabeth, daughter of the fourth Earl of Douglas, he

had a son and daughter. Katherine, the daughter, married Alexander, Duke

of Albany, son of James II., and was divorced, while William the son was

left by his father only the estate of Newburgh in Aberdeenshire and the

title of Lord Sinclair, by which title the earl had been called to

Parliament in 1449. In 1676 this title of Baron St. Clair passed through a

female heir, Katherine, Mistress of Sinclair, to her son Henry St. Clair,

representative of the family of Sinclair of Herdmonstoun. Through his

daughter Grisel and two successive female heirs the estates passed to the

family of Anstruther Thomson of Charleton, while the title of Lord

Sinclair was inherited by the descendants of his uncle Matthew. The

present Lords Sinclair are therefore of the family of Herdmonstoun, and

are not descended from the original holder of the title, the great

William, Earl of Orkney and Caithness and Chancellor of Scotland, of the

days of James II. and III.

Earl William’s second wife was a daughter

of Alexander Sutherland of Dunbeath, and by her, besides other children,

he had two sons. To one of these, William, he left the earldom of

Caithness, and to the other, Sir Oliver, he left Roslyn and the Fife

estates. It is from the former that the Earls of Caithness of the present

day are directly descended.

William, the second Earl, was one of the

twelve great nobles of that rank who fell with James IV. on Flodden field.

So many of the Caithness men were killed on that occasion that since then

the Sinclairs have had the strongest aversion to clothe themselves in

green or to cross the Ord Hill on a Monday; for it was in green and on a

Monday that they marched over the Ord Hill to that disastrous battle. So

great was the disaster to the north that scarcely a family of note in the

Sinclair country but lost the representative of its name.

John, the third Earl, was not less

unfortunate. In 1529, ambitious of recovering for himself his grandfather’s

earldom of Orkney, and of establishing himself there as an independent

prince, he raised a formidable force and set sail to possess himself of

the island. The enterprise was short-lived, most of the natives of the

islands remained loyal to James V., and, led by James Sinclair, the

governor, they put to sea, and in a naval battle defeated and slew the

Earl with 500 of his followers, making prisoners of the rest.

George, the fourth Earl, has a place in

history chiefly by reason of the sorrows and indignities he had to suffer

at the hands of his eldest son. That eldest son, John, Lord Berriedale,

Master of Caithness, induced his father in 1543 to resign the earldom to

him. He married Jean, daughter of Patrick, third Earl of Bothwell, and

widow of John Stewart, prior of Coldingham, a natural son of James V., and

he set out to aggrandise himself by most unnatural means. Among other

exploits he imprisoned his father, and in 1573 strangled his younger

brother, William Sinclair of Mey. Earl George himself was mixed up in the

history of his time in a somewhat questionable way. In 1555 he was

imprisoned and fined for neglecting to attend the courts of the Regent. As

a Lord of Parliament in 1560 he opposed the ratification of the Confession

of Faith, when that document was abruptly placed upon the statute book. He

was made hereditary justiciar in Caithness in 1566, but that did not

prevent him taking part in the plot for the murder of Darnley in the

following year, nor again did this prevent him from presiding at the trial

of the chief conspirator, the Earl of Bothwell. Among his other actions he

signed the letter of the rebel lords to Queen Elizabeth in 1570, and was

accused of being an instigator of crimes in the north.

His son, the Master of

Caithness, being dead five years before him, in 1577, he was succeeded by

the Master’s eldest son, George, as fifth Earl. This personage, in the

days of James VI. and Charles I., engaged in feuds, raids, and other

similar enterprises which seemed almost out of date at that late period.

It was he who in 1616 instigated John Gunn, chief of that clan, to burn

the corn-stacks of some of his enemies, an exploit which secured Gunn a

rigorous prosecution and imprisonment in Edinburgh; and it was he who in

1585 joined the Earl of Sutherland in making war upon the Gunns, in the

course of which undertaking, at the battle of Bengrian, the Sinclairs,

rushing prematurely to the attack, were overwhelmed by the arrow-flight

and charge of the Gunns, and lost their commander with 120 of his men. The

Earl’s great feud, however, was that against the Earl of Sutherland

himself. The feud began with the slaughter of George Gordon of Marle by

some of the Caithness men in 1588. By way of retaliation the Earl of

Sutherland sent into Caithness 200 men who ravaged the parishes of

Latherone and Dunbeath; then, following them up, he himself overran the

Sinclair country, and besieged the Earl of Caithness in Castle Sinclair.

The stronghold proved impregnable, and when Sutherland retired after a

long and unsuccessful siege, Caithness assembled his whole clan, marched

into Sutherlandshire with fire and sword, defeated his enemies in a

pitched battle, and carried off much spoil. Sutherland retaliated in turn,

300 of his men spoiling and wasting Caithness, killing over thirty of

thejr enemies, and bringing back a great booty. The Sinclairs again made

reprisals with their whole force. As they returned with their plunder they

were attacked at Clyne by the Sutherland men to the number of about 500,

but maintained a desperate fight till nightfall, and then managed to make

off. On reaching home, however, they found that the Mackays had raided

their country from the other side, and, after spreading desolation and

gathering spoil, had retired as suddenly as they had come. When these

raids and counter-raids with the men of Sutherland were over, the Earl of

Caithness found other openings for his turbulent enterprist. After

committing an outrage on the servants of the Earl of Orkney, he earned

credit to himself by putting down the rebellion of Orkney’s son, and for

this in 1615 received a pension. Having, however, committed certain

outrages on Lord Forbes, he was obliged to resign his pension and the

sheriffdom of Caithness in order to obtain pardon. For his various acts a

commission of fire and sword was issued against him, and he was driven to

seek refuge in Shetland. It was not long before he was allowed to return,

but he did so only to meet his creditors, and at his death twenty years

later he left his affairs still in a state of embarrassment.

The son and grandson of the fifth Earl

having died before him, he was succeeded as sixth Earl by his great

grandson, George. The career of this Earl and of his rival, the astute and

unscrupulous Sir John Campbell, Bart., of Glenurchy, reads almost like the

pages of a melodrama, and still forms the subject of many a tradition

repeated among the people of Caithness. The Chief of the Sinclairs,

helped, it is said, by the machinations of Glenurchy, found himself more

and more deeply involved in debt. There are stories of his raising money

upon mortgage to help friends who were in turn in the power of Glenurchy,

and of the mortgages and loans alike finding their way into Glenurchy’s

hands. Finally in 1672, the Earl, finding himself involved beyond

recovery, was forced to make over to Glenurchy, as his principal creditor,

a wadset, not only of his lands, but also of his honours. The wadset was

to be redeemable within six years, but after that time the right to the

lands was to become absolute and the title of Earl of Caithness was to

pass to Glenurchy. Four years later the Earl of Caithness died, and two

years later still Glenurchy married his widow, Mary, daughter of

Archibald, the notorious Marquess of Argyle. At the same time, the period

of the wadset having arrived, Glenurchy laid claim to the lands and title

of the Earldom of Caithness. His claim was resisted by the heir male,

George Sinclair of Keiss, son of the second son of the fifth Earl. King

Charles II., deciding that the right belonged to Campbell, granted him a

new charter, including both title and estates, but when Glenurchy tried to

collect his rents he found the Sinclairs refuse to pay. In order to

enforce his right Glenurchy, who was now Earl of Caithness, sent into the

north a body of men under his kinsman, Robert Campbell of Glenlyon,

afterwards notorious as captain of the force which carried out the

Massacre of Glencoe. The Campbells marched northward till they were

confronted by the forces of the Sinclairs on the further bank of a stream.

For a time, it is said, they remained there, neither side venturing an

attack; but at last Campbell sent a convoy of French wines and spirits

along a road on which he knew it must fall into the hands of the Sinclairs.

That night there were sounds of merrymaking in the camp of the latter.

When these sounds had died away, and Glenlyon judged his opponents to be

unlikely to make effective resistance, he marched his men across the

stream, and cut the Sinclairs to pieces. As he did this, the pipers of the

Campbells played for the first time the pibroch, Bodach an Briogas, the

Lad of the Breeches, in derision of the Sinclairs, who wore, not the kilt,

but the trews. The tune has ever since been the gathering piece of the

Campbells of Breadalbane.

But though Glenlyon had routed the

Sinclairs, King Charles shortly afterwards became convinced that he had

made an error, and in 1680 he caused Glenurchy to relinquish the earldom

of Caithness, recompensing him at the same time by creating him Earl of

Breadalbane and Holland. George Sinclair of Keiss who thus became seventh

Earl, died unmarried in 1698, and the family honours devolved on John,

grandson of Sir James Sinclair of Murchill, brother of the fifth Earl. Sir

James had married Elizabeth, daughter of Robert, Earl of Strathearn and

Orkney, a natural son of James V., so John, who succeeded as eighth Earl,

was a great-great-grandson of the gay "guidman of Ballengeich."

At this period the Jacobite Rebellion of

1745 took place. According to the estimate of President Forbes of

Culloden, the Sinclairs could then raise 1,000 men. Five hundred of them

actually took arms, and were on their way to join Prince Charles when news

of the defeat of the cause at Culloden reached them and caused them to

disband.

On the death of Alexander, ninth Earl of

Caithness, without a male heir, the earldom was claimed by a grandson of

David Sinclair of Broynach, brother of the eighth Earl. The claimant’s

father was understood to have been illegitimate, but it was sought to be

proved that he had been legitimated by a subsequent marriage of David of

Broynach to his mother. Both in 1768 and 1786, however, the courts

repelled this claim, and the earldom accordingly passed to William

Sinclair of Ratter, representative of Sir John Sinclair of Greenland,

third son of the Master of Caithness, fourth Earl. The son of this Earl

was again the last of his line, and the earldom passed to Sir James

Sinclair, Bait., of Mey, representative of. George Sinclair of Mey, third

son of the fourth ‘Earl. This peer, who was the twelfth Earl of

Caithness, was Lord Lieutenant of the county, and became

Postmaster-General in 1810. Alexander, his second son, who succeeded him,

was also Lord Lieutenant, and his son, James, the fourteenth Earl, after

being for a time a representative peer, was created a peer of the United

Kingdom as Baron Barrogill in 1866. This honour became extinct on the

death of his only son, George, fifteenth Earl, in 1889. The Scottish

honours then passed to James Augustus Sinclair, representative of Robert

Sinclair of Durran, third son of Sir James Sinclair, first baronet of Mey,

grandson of George Sinclair of Mey, third son of the fourth Earl; and the

present Earl of Caithness, who in 1914 succeeded his elder brother as

eighteenth Earl, is his second son.

Probably none of the ancient peerages of

Scotland has passed so often to collateral heirs as has the earldom of

Caithness since the death of George, sixth holder of the title, In 1676.

The present chief of the Sinclairs is still, however, representative by

direct male descent of the doughty Lords of Roslyn of the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries.

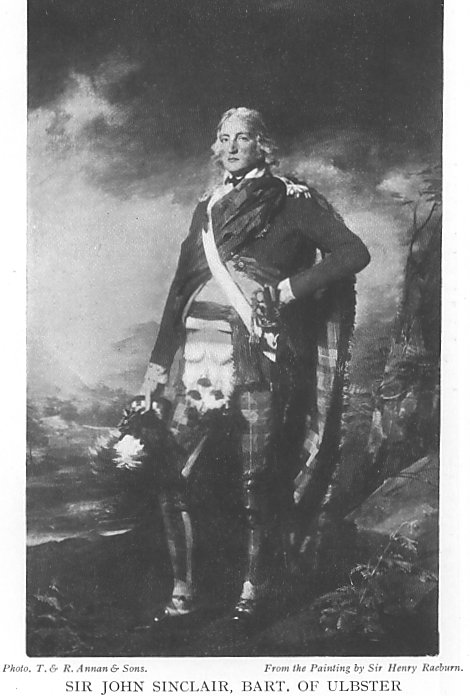

Of cadet houses of the name, the two most

noted are those of Sinclair of Ulbster and Sinclair of Dunbeath. The

former of these is descended from Patrick, elder legitimated son of

William Sinclair of Mey, second son of the fourth Earl, who was strangled

by his brother, the Master of Caithness, in 1573. Of this family John

Sinclair of Ulbster became Hereditary Sheriff of Caithness at the

beginning of the eighteenth century, and Sir John Sinclair, first baronet

of Ulbster, whose mother was sister of the seventeenth Earl of Sutherland,

remains famous as the greatest improver of Scottish agriculture, founder

and President of the Board of Agriculture, and compiler of that

indispensable work, the Statistical Account of Scotland. He raised

from among the clansmen two Fencible regiments each 1,000 strong, and was

the first to extend the services of these troops beyond Scotland. Sir

John, who was a Privy Councillor and cashier of the Excise in Scotland,

died in 1835, and the present baronet of Ulbster is his

great-great-grandson.

The Sinclairs of Dunbeath, again, are

descended from Alexander Sinclair of Latheron, youngest son of George

Sinclair of Mey, third son of the fourth Earl, who married Margaret,

daughter of William, seventh Lord Forbes. The baronetcy dates from 1704,

and the house has been notable for its distinguished services in the Army

and in Parliament, one of its members being the Rt. Hon. John Sinclair,

Lord Pentland, who was Secretary of State for Scotland in 1905, married

a daughter of the Marquess of Aberdeen!, was raised to the peerage in

1909, and has been Governor of Madras since 1912.

Among other notable personages of the name

have been Oliver Sinclair, the notorious general of James V., who was

defeated and captured by the English at Solway Moss in 1542, and released

on condition of furthering the English interest. His brother, Henry

Sinclair, Bishop of Ross, and President of the Court of Session, was a

member of Queen Mary’s Privy Council, had the distinction of being

denounced by John Knox, and wrote additions to Boece’s History of

Scotland. Another distinguished brother was John Sinclair, Bishop of

Brechin, who was believed to be the author of Sinclair’s Practicks, was

also denounced by John Knox, and officiated at the marriage of the Queen

to Darnley in 1565. There was, again, the famous Master of Sinclair, son

of the tenth Lord Sinclair. While serving with Marlborough in Flanders in

1708, he was sentenced to death for shooting Captain Shaw, and fled to

Prussia till pardoned in 1712. During the rebellion of 1715 he

distinguished himself by the capture, at Burntisland, near his own family

estates, of a ship with Government munitions of war, destined for the Earl

of Sutherland at Dunrobin. He was attainted, but pardoned in 1726, and was

the author of Memoirs of the Rebellion, printed in 1858. A notable

author of the name was George Sinclair, who died in 1696. Professor of

Philosophy at Glasgow, he was compelled to resign for non-compliance with

Episcopacy, but was reappointed after the Revolution. He was associated

with the inventor in the use of the diving-bell, was one of the first in

Scotland to use the barometer, and superintended the laying of Edinburgh

water-pipes in 1673.

Septs of Clan Sinclair: Caird, Clyne.

This is the American

contingent at an early evening lawn party and reception hosted by Viscount

John Thurso in 2005 (fellow in kilt and red sweater second row left) at his

estate of Thurso East. Malcolm Caithness, Chief of Clan Sinclair, is the

gentleman third from right in second row. Isla St Clair, singer and

musician, is far right on second row.

|