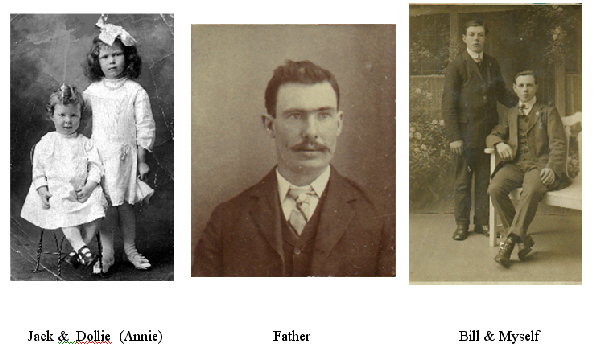

My father,

Thomas Mathieson Sutherland (Sr.), was born in Gallonfield, (Gollanfield?)

Inverness shire, Scotland, in 1870. There is a story about the name "Mathieson"

and, as I recall it, one of our forbears was such a bonnie lad that a

well‑to‑do man named Mathieson wanted to adopt him and make him the

heir. However, those responsible did not wish to see the name

"Sutherland supplanted by "Mathieson" and the offer was declined, but

the name "Mathieson" was integrated in the lad's name.

I do

not remember Grandfather Sutherland, although I have a vague

recollection of visiting Granny Sutherland who lived in a cottage on the

shore of the North Sea, almost in the shadow of Fort George in the

vicinity of the city of Inverness. One day while the folks were wading,

or however they frolicked in those days in the water, they noticed me

walking back towards Granny's home. When they caught up to me I told

them I was on the way to get a kettle of hot water to warm the sea.

Dad,

and his sister Bella, were the youngest in the family (there were over a

dozen of them and I can recall seeing a photograph of the whole family,

Dad and Aunt Bella being seated on the floor in front of the group ‑ all

of the male members of the family sported full beards.

Dad's

eldest sister, Mary, was quite an influence in his life. She married

Malcolm Bruce who became the head Steward in Lamb's Hotel, a temperance

house in Dundee. Uncle Malcolm sent Dad "The British Weekly" for many

years. I have the impression that Dad was with the Glasgow Police for a

time, and he studied at the Glasgow Bible Training Institute, part of

the student's' duties being to go out and conduct street corner meetings

in the evenings.

Mother, Margret Wilson Sloan, was born in 1872 in Howwood, Renfrewshire,

where her father, William Sloan, among other things, was the local

postman. She had one brother, Will (Wull) who was married and lived in

Paisley; three sisters, Flora (Mrs. Archie Whitehead) a widow; Mary

(Mrs. Robert Moore, and Annie who married later and moved to Eccles,

near Manchester.

Mother

and Dad were married in Goven early in 1898 and they lived in Howwood

where Dad worked in a local mill as a cloth finisher.

I,

also Thomas Mathieson Sutherland, was born in June (23), 1899, and I

remember we lived in one of the two gate houses on either side of the

"policy" (driveway) leading to Castle Semple ‑ which sounds like the

place Rudolf Hess was heading for when he landed in Scotland and was

made prisoner‑of‑war. Dad's sister Bella (Mrs. Andrew Eason) and family

lived in the opposite gate house as her husband was a gamekeeper on the

estate. I have a recollection that "Uncle Andrew was home from the war"

‑ the South African War. After a shooting party on the estate the dead

hares were left in a pile near their house. My cousin Andrew Eason was

about my age and we were curious about what happened when we squeezed

the carcasses. I went fishing by dangling a string from a small stone

bridge over the White Cart, a small stream nearby.

They

used to tell of an evening when dad took me with him when he went to

attend a meeting of the com‑mit‑ee of the "Co", the local Co‑Operative

shop. He left me at Aunt Flor's and they say I spent the whole evening

greeting (crying) and pleading "Take me to my daddy".

We

later moved to Wardrop Terrace in the village where it was a pleasure to

climb into bed with mother after dad had gone to work, but having to

yield the favored spot in time to another and be content to lie

"back‑to‑back" with her. Then there were the Sunday morning walks with

"Faither" along the country road past farms hearing the sounds of

poultry, sheep, cattle and horses from the fields and byres, and church

bells ringing in the distance as we made our way along the three mile

walk to "kirk" in Kilbarchan.

I had

a scar from "scabby face" (impetigo?) and a cut scar from the tip of my

right thumb to beyond the first joint, and these, with all my freckles,

were erased in 1918 when I was severely burned. I had scarlet fever and

was in a nearby hospital ward with other youngsters, and the blinds were

drawn. As we recovered great patches of skin were sloughed off, the

sole of one lad's foot peeling off in one piece. When returning home we

passed a building with a "black flag" and I was told it was a jail , and

the black flag was flying because someone had been hung that day.

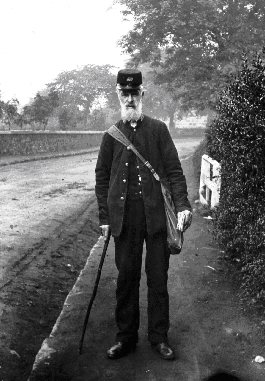

Father Sloan

Mother

Sloan

The Sloan Family

Will

Margaret (Maggie) Father (William) Mother (Ann) Flora or Mary

Annie

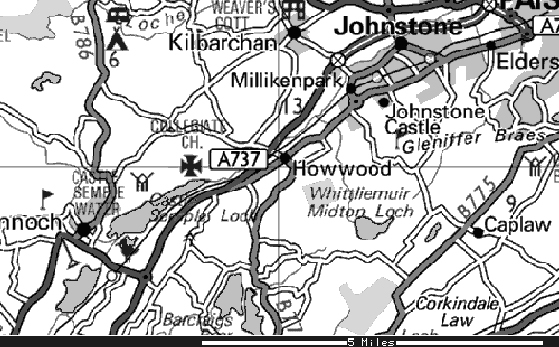

Expanded map of the area

showing Castle Semple Water, Castle Semple Loch, and the Collegiate

Church. Also shown is the town of Kilbarchan mentioned in the text.

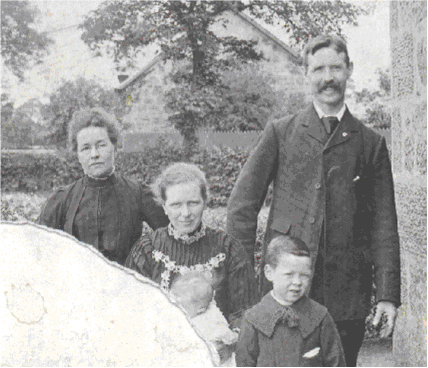

Left: Aunt Mary (Sloan)

Moore. Right: Father

One

day when Granny and Aunt Flora were in having tea with mother, Willie (Wullie)

Whitehead, another cousin about my age, and I were having fun jumping on

a board over a little "burn" splashing water up , when through the

bushes we saw Agrandfaither@ coming along the bank. He called to us,

but we took to our heels and headed for Wardrop Terrace and managed to

get in and shut the door before he got there. I was next the door knob

and when he forced the door open I was pushed up the stairs and kept on

going, but Wullie Whitehead was trapped behind the door. I went in to

the room where the folks were, and when they asked about the commotion "doon

stairs" I said "Grandfaither was leathering Wullie Whitehead."

William Mathieson was born in 1901, and I recall his first accident

several years later when we were trying to see Christmas goods in the

window of a shop. The window was too high for us to see well, so we

stood back then ran and got a toe on a protruding stone which enabled us

to get a momentary glimpse of what was displayed inside. Unfortunately,

Bill stumbled and fell smashing his forehead against the stone he should

have put his toe on ‑ he had a cross shaped scar on his forehead for the

rest of his life. He and I sometimes stood on the "green" below the

second floor window where we lived, and we would call until mother

appeared and we would ask her to "throw doon a piece and jeely" and

would wait until she tossed down a paper wrapped packet holding a jam or

jelly sandwich. From the upstairs window on the other side of the

terrace we could look down on the street and see what was moving, maybe

a steam lorry, perhaps a "Punch and Judy" show, or the ice cream wafer

man.

Isabella Cameron was born in 1905. Selecting a name for the first

daughter was a problem. Dad's mother was "Bella" and mother's "Annie",

but Annabella was out of the question as that was the name of a

notorious woman in the area. Hallow E'en was a festive occasion, with

groups of youngsters going from door putting on little performances, one

being a story by two youngsters in costume, and it went something like

this:

"Here come

I, Gilloshawa.

Gilloshawa is my name.

My sword and pistol by my side

I hope to win some fame."

"Some fame,

sir, some fame?

That's not within your power.

I'll cut you down to inches

inside of half an hour!"

Then the

two would go into their performance. Other visitors might be

blindfolded and led to the hearth where bowls were lined up containing

various objects or ingredients, their fortunes being told according to

the contents of the bowl they touched , and, of course, there was the

usual ducking for apples.

Grace

Moffat (left) with Mother (centre) and Father (right). TMS lower right

about 5 years old. Partial baby probably Isabella and William may have

been on the torn corner part.

Left:

Mother, Father and TMS about 2 years old and Right: Grace Moffat and

Mother

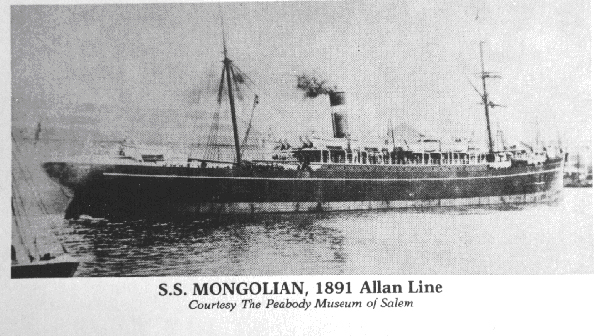

Times

were difficult, and mother's sister Mary and her husband, Robert Moore,

with his brother Wilson and family, emigrated to Canada and settled in

Elgin, Manitoba, a "local option" area. Good news was received from

Canada, and late in May, 1905, we sailed from Glasgow on the Allen liner

"Mongolian". As the lines were being cast off, the people on the ship

joined with those on shore in singing "God be with you till we meet

again." I don't remember much about the voyage, but dad kept a diary,

and in after years we youngsters enjoyed reading it, always getting a

laugh when we read "Maggie had the colley wobbles this morning."

Elgin

was on a Canadian Northern branch line about a hundred and sixty miles

southwest of Winnipeg, served by daily passenger trains to and from

Winnipeg, and, of course, freight trains. We lived in a small house

next the "Hornerite" (holy roller) church. There was a little heater in

the room where dad and mother slept, and one morning mother got up, put

some kindling in the heater and threw in some coal oil. The ashes must

have been hot for flames immediately flashed out and mothers

flannelette nightie blazed up. Dad was right there and managed to

smother the flames and mother wasn't injured.

Shortly after our arrival in Elgin, a letter was received from Dundee

telling us that Polly, one of the Bruce daughters was quite ill. She

wakened from a nap one day and said to Aunt Mary, "I just had a

wonderful dream. Jesus came to me and said "Not yet, daughter, but in a

fortnight, and your mother will be with you in a month." They were both

buried inside that period.

There

was an eclipse of the moon about that time, and it had been explained to

me in such a way that when the eclipse was in progress I thought I could

see pieces of the moon being cut off and falling to the ground in the

shape of orange sections.

In

Elgin, steady jobs were few, particularly for newcomers, and Dad had to

turn his hand at anything he could find to do. He began to do a lot of

painting of houses (white with green trim) and barns (red) in Elgin and

neighboring communities. On a shed at one of the farm homes he painted

(exactly as he might have written it in longhand) "Laugh and the world

laughs with you. Weep, and you weep alone."

He

also took an active part in church affairs, and at home we had scripture

reading and prayers, morning and evening. There were two texts (silver

letters on a dark background) which hung on the walls of the homes we

occupied, one being John 3:16, and the other

"God is the

head of this house.

The unseen guest at every meal.

The silent listener to every conversation.

In all thy ways acknowledge Him and

He will direct thy path."

The

strongest expressions we heard Dad use were "dash it", which with his

accent sounded like "daysh it," or "confound it". All weekend chores

had to be completed on Saturday, wood brought in, water pails filled,

boots polished (Dad even polished the insteps of his boots), and, of

course, it was the weekly bath night with a tub of water in the middle

of the floor in which each in turn took his or her place, perhaps the

younger ones doubling up. Sunday was a day for worship ‑ no whistling

unless it was a hymn tune, no reading of secular material unless it was

in a Sunday school paper and no playing of games.

One

winter, it must have been about 1907 or 08, because of storms and heavy

snowfalls, we didn't get a train in Elgin for three weeks. The village

was running short of fuel and food when word was received that a train

was on it's way. All the men in the place turned out with shovels to

attack the snowdrifts in an endeavor to expedite the movement of the

snowplow and relief train, but when the train arrived they learned that

the last fuel car had been set off two or three stations away.

When

dad couldn't get work, particularly in the winter, we just had to make

do as best we could. He used to tell of sitting one night wracking his

brains to devise ways to make ends meet as there wasn't a cent in the

house, when he heard a knock at the door, and when he opened it there

was no one there, but a bag of groceries was lying on the doorstep.

Next

we lived in the McBurney house, and one evening Dad took me with him for

a walk, and he went to the baker's shop where pails of candy were

leaning against a counter. While Dad and the baker were talking, I

looked over the contents of the pails and took a few samples. When we

got home, I shared the candies with Bill and Bella. Dad saw and asked

where I had got the candy. I told him, and he promptly marched me back

to the baker's shop and made me tell the baker what I had done. It had

such an impression on me that I did not do it again.

There

was a low stable in the back yard, and it had a curved roof and a pile

of straw lay at one end. We sometimes climbed up on the roof and jumped

down on the straw. One day I wasn't satisfied just to drop down on the

straw but went to the far end and ran the length of the roof and then

jumped ‑ to my sorrow, for I landed on the ground beyond the pile of

straw and sprained my ankles. A few days later I was able to hobble on

my left foot, using a stick in both hands to take the weight off my

right foot as I hopped with the left. It was quite a while before I

could bear any weight on the right, and then if I made a quick move pain

shot through it and I could only limp. In fact, even yet I get a twinge

of pain if weight is suddenly put on that foot.

One

Saturday morning, several youngsters of the neighborhood accompanied

Bill and me on a walk to "Uncle Wilson's" farm some miles away. As we

wandered a bit before getting there, Uncle Wilson held me up to see the

elevators in Elgin so that we would go in the right direction. When we

got home shortly before supper, we found that there had been quite a bit

of consternation when our absence was noticed, and we were given a

stern lecture not to go off like than again without letting someone know

what we had in mind.

We

moved to the "Craig shack" and remained there until we left Elgin. It

had a stable and in the course of time Dad acquired a horse, a cow, and

some hens. I was in the stable one day and noticed that a hen had been

sitting in her nest for quite a while, so I stayed around, and when she

dropped her egg I saw that it had a film of moisture on it which quickly

dried.

We

had a garden and grew potatoes, onions, radishes, lettuce, etc., and of

course potato bugs. I began to have chores to do ‑ take the cow to

pasture each morning and bring her back at night to be milked. The

pasture was along a ravine which ran with water in the spring. Part of

it had apparently been a buffalo wallow, and there was a large stone

which we thought the buffalo had used for rubbing as it was very

smooth. When we had spare milk, I delivered it to customers, 5 cents

a quart, and when there was an accumulation of sour cream, butter was

made in a "dash" churn. Dad and Mother were fond of "soor dook", their

name for buttermilk. We didn't have a well and water had to be brought

from a neighbor's well. Firewood also had to be chopped and brought in.

Sometimes when mother was out visiting Aunt Mary, I made pancakes if I

could find sour milk, and the others liked them so much that they would

even bite a cake of soap to get one.

The

first automobile I can remember seemed to be just like a buggy except

that it had an engine under the seat, and a perpendicular seat in front

on which a horizontal steering wheel was mounted.

In

Elgin the Baptists held their meetings in the "Orange" Hall, and we

attended Sunday school in the Methodist church. The Methodist and

Presbyterian churches were practically back to back, and in summer when

windows were open everything was audible outside ‑ giving rise to the

story that there had been an occasion while one congregation was singing

"Will there be any stars, any stars in my crown" the other was

melodiously singing "No not one, no not one,"

The

C.N.R. excursion train to Ninette and Pelican Lake was a yearly event,

and the Sunday Schools in the villages along the line would make it the

occasion for their annual picnic. We went to Ninette one year where we

played along the beach and got wet. I wandered a bit and saw a man

inviting people to get into his launch and enjoy an outing on the lake.

I was much taken aback when the man came around collecting fares which I

knew nothing about and I didn't have a cent. He put his hands in my

armpits and made a motion as though he was going to throw me overboard,

and the other passengers seemed to be enjoying his joke.

Horses were the means of locomotion in those days, and, like kids in

later years who prided themselves on being able to name each automobile

they saw, we were able to name the breeds of horses we saw ‑ Clydes,

Percherons and Belgians being some of the heavy work horses. There were

of course lighter horses and ponies for drawing carts, buggies,

democrats, etc. The owner of a Shetland pony was a proud boy.

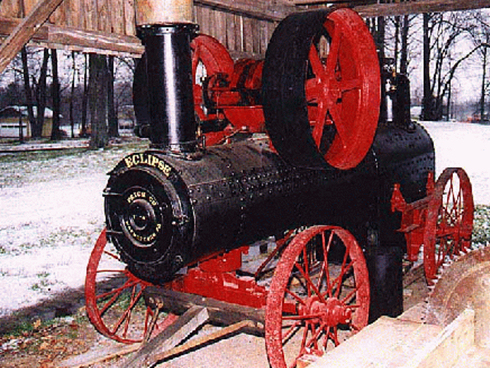

A

threshing outfit in a nearby field had to be visited. A team of horses

pulled the stationary steam engine and a four horse team pulled the

separator into their respective positions in the field to be threshed,

wind direction being a controlling factor. A long, wide belt conveyed

power from the engine to the separator, and when the straw being

threshed reached the lowest point in its journey through the separator,

it was deposited on an incline and dropped on the ground beyond the

separator. When a pile reached the height of the separator it was moved

away by a "buckboard", two long heavy planks boarded together with a

metal loop and singletree at each end to which a horse was hitched. The

two horses were some distance apart, but one man handled them and moved

the pile of straw alternately in each direction from the separator to

make room for more straw. We kids liked to catch hold of the buckboard

and be dragged along on it's moves, but occasionally the buckboard

wouldn't strike the pile at the right angle and would go right through

it leaving us buried in the middle. That was all right so long as the

man driving the rack to get straw to fuel the engine didn't come along

to get a load. A fireman had a steady job feeding straw into the

firebox with a straw fork which had a long metal shank and a wooden hand

grip. Another essential part of the threshing outfit was the water tank

to supply water to the engine, and it was usually equipped with a bucket

sized dipper and a long handle, or a pump with a hose to enable them to

get water from the nearest slough, or other source. At the end of the

day, the engine and separator were moved away from the piles of straw

which were set on fire.

In

later years, traction (self‑propelled) engines were used, and a "blower"

became part of the separator (a fan directing straw and chaff into an

adjustable metal spout) allowing the straw to be blown into a high

stack. The threshing outfit had to be located in each field in such a

way that the engine was up wind from the separator, and at the close of

the day the usual precautions had to be taken, as in the evening many

straw fires were reflected in the clouds.

Malcolm Alexander was born in 1906 and Annie Love in 1908. Love was

Granny Sloan's maiden name. In a small town youngsters had to devise

their own amusements. When spring came, there was an unspoken contest

to see who would be the first to come to school in bare feet, stockings

and boots being cached under the wooden sidewalk. Of course, in summer

all kids were in bare feet and by fall the soles of their feet had

become so calloused they could walk over gravel or thistles without

discomfort ‑ foot washing was a nightly necessity.

The

blacksmith shop was a magnet for it was interesting to stand in the

doorway seeing sparks flying as the blacksmith fashioned white‑hot metal

into horse shoes, or other articles, his hammer ringing as he tapped the

anvil. One might be given an opportunity to operate the bellows or

whatever device was being used to stimulate the fire in the forge.

There was the unexpected thrill when the blacksmith handed one a piece

of metal to hold for him ‑ but it was promptly dropped as it was too hot

to be held by any but a calloused hand. One wondered how he knew how

much hoof to pare away before clamping a red hot shoe against a hoof to

burn a seat for it before dipping it into water to cool it before

nailing it in place.

A horse drawn steam

engine of the period. The belt to the separator is attached to

the flywheel

The separator is being driven by the belt.

The wagon brings the grain to be threshed to the separator and the straw

is thrown out the other end. The grain is collected in the truck at

left.

A self

propelled steam engine of later vintage (1916)

A newer type threshing machine with a blower

for disposing of the straw.

The tall pipe is the straw chute. A screw feeder sends grain to the

truck at right.

The

railway station, and it's sidetrack along which the elevators stood, was

always an attraction. Those were the days when lead seals were used

and discarded seals were always lying around, waiting for someone to

pick them up and lay them on a rail for a passing engine to flatten

them. There were usually cars standing on the sidetrack, and we enjoyed

climbing up the ladders and running along the top. The discarded

screenings at the elevators were usually left in an open bin and were

sometimes picked up to be taken home and used as chicken feed. There

was often water lying in the ditch and we made rafts using ties which

weren't in service. Sometimes we youngsters would go skinny‑dipping ‑

lads with eight or nine year old wisdom telling us "Pee down your legs

and you won't get rheumatism."

In

winter when snowfall became general, buggies gave way to cutters, wagons

to bob sleighs, and sleigh bells jingled merrily, and we would take our

hand sleighs and loop the rope through the runners of cutters or bob

sleighs we had spotted leaving town, and went with them until we met

another rig coming into town. Sometimes the drivers would whip up the

horses to give us a fast ride, or to evade us, but it was all done in

good fun, although sometimes it might be a weary walk back to town.

About

1908, Bill was the victim of a serious accident. A traction engine was

on one of the flat cars set off at the loading platform, and a number of

us were having a heyday examining it, when someone called "Here comes

the Cannonball", our name for the evening passenger train from Winnipeg

and we all headed for the station to be on the platform when the train

arrived, that being one of the highlights of the day. Some of the lads

crossed over in front of the train but I waited until it had passed,

then crossed over the track and saw Bill lying in the ditch. People on

the street had seen what happened and they were on the scene almost as

soon as me, and he was picked up and taken to the doctor's office. The

livery man dispatched a fast team to get dad who was painting a barn in

the Fairfax district. The doctor said the injury was so serious that

Bill wouldn't live the night, but as he was still alive the following

day they operated and removed fragments of the skull from his brain, the

injury being just below his crown. The C.N. sent a nurse from Winnipeg

and Bill was unconscious for two weeks and he was accommodated in the

home of the Randolph Sparrows for about two months. Some portion of his

brain was permanently damaged, and he did not get beyond Grade 3 in

school. In later life he seemed to get most enjoyment when playing with

children of the age he was when he was injured. Several weeks after he

came home, he was standing on a chair and fell off, sustaining a severe

cut on his forehead.

We had

a washing machine with a toothed bar operating back and forth across the

top of the lid agitating the dolly washing the clothes. I wasn't in the

house when it happened, but the kids managed to get the flywheel under

the tub, which gave momentum to the toothed bar, in motion and they then

vied with each other to see how close they could hold a finger to the

point where the toothed bar engaged the dolly. Malcolm Alexander got

into the competition, but didn't get his finger away in time and it was

caught and squeezed. Fortunately only flesh was involved.

Dad

had carried on his religious work throughout the years, and in addition

to painting he had done some preaching. On one occasion he went to

Otturburne, a village south of Winnipeg to speak to a Baptist

congregation, but concluded the place wasn't for him because it was an

R.C. community and the people spoke French rather than English.

Mother

was a homey person, industrious and frugal (of necessity) and on one

occasion she and Aunt Mary made soap using lye and other ingredients.

In Dad's absences, I became very close to her. She baked bread for the

family preparing the dough with potato water and yeast, leaving the

dough in a large pan, warmly wrapped, to "rise" overnight. The

following day she would knead the dough and put it in pans to be baked.

The "heel" of a freshly baked loaf was coveted. She baked scones which

I now know as baking powder biscuits, and they were broken open when hot

and eaten while the butter was melting after being fortified with a

dash of pepper. Currant and custard pies were also favorites, and

another delicacy was canned rhubarb, a piece of ginger root being

inserted into the seals as they were being closed.

Nineteen ten was an eventful year. Dad had spent the previous winter

preaching at Marquis, Keeler and Brownlee, northwest of Moose Jaw

(probably for the Presbyterians). King Edward VII died, and Halley's

comet could be seen each evening as it travelled across the western

sky. The earth was to pass through the tail of the comet one night and

I stayed up to see what happened. I might as well have gone to sleep.

Dad

and I attended a memorial service for King Edward in the "English"

church. It was the first time I had been in such an edifice, and during

the course of the service I braced my feet against something, and

stretched, when the kneeling bench tipped over with a terrifying crash

right in the middle of the solemn service.

Dad

was invited to take charge of a Baptist congregation in Glen Ewen,

Sask., and we moved there that fall, and we were there when King George

V was crowned in 1911. Before leaving Elgin, dad took me with him when

he went to pick up "Madge", a balky horse he owned. On the way home I

drove and dad held Madge's lead rope. She suddenly stopped and Dad's

hands automatically closed on the rope which burned through his hands

before I could bring the buggy to a quick stop.

Dad

went on ahead to Glen Ewen, and to get there it was necessary for mother

and the family to drive fourteen miles to Hartney to catch the C.P.R.

train. Mother also hand baggage and five youngsters to look after, and

shortly before the train was due to arrive at Hartney, she couldn't find

her handbag which contained our tickets, etc., Everybody assisted in a

frantic search for it, but it couldn't be found. The station agent got

in touch with Glen Ewen, and was assured that the conductor would carry

us to Glen Ewen without tickets, and Glen Ewen would get the fares. A

couple of weeks after we got to Glen Ewen word was received that

mother's handbag, with it's contents intact, had been found in the "wee

hoose" at Hartney where she had laid it in a dark corner, such

facilities having little illumination.

At

Glen Ewen in 1911, John Moffat was born (Grace Moffat had been mother's

dear friend in Scotland). I well remember the morning. Facilities in

the house were limited, and the first thing in the morning was to use

the facilities in the washstand in our parent's room. That morning I

went to go in there when the door was slammed in my face so sharply that

I was thrown against the opposite wall.

Houses

in those days were heated by a stove or range with a high "warming

oven", and auxiliary heaters might be in other rooms. A "reservoir"

adjacent to the oven was kept well replenished, the water being warmed

by it's proximity to the fire. The stoves were usually fired by wood in

summer and "Galt" coal in winter, and the stovepipes conveyed the smoke

to the chimney adding a measure of heat to the rooms through which they

passed..

In

rural homes basements as such were unknown, but there was usually a

cellar, a shallow pit entered through a trap door in the kitchen floor.

I remember a home near Elgin where they had a "cooler" in the cellar ‑

they pulled up a section of the floor and it had several shelves

attached to it, counter weights having made it easier to pull up or

lower.

One

day, at Glen Ewen, the trap door had been left open and Annie

disappeared into it, but as the door slammed shut a small piece of

Bella's skirt was caught and held her in mid air, howling. As it was

impossible to get a grip on the small piece of cloth, and as she

wouldn't have much farther to fall if the door was opened, it was

decided that was what had to be done. Annie was badly scared but was

otherwise uninjured.

But

that wasn't the only mishap that occurred at Glen Ewen ‑ Malcolm wasn't

going to school and often accompanied the drayman on his deliveries. On

one occasion the team decided they wouldn't wait for the driver to

return and they took off at full gallop around the village, then

decided to head for the livery barn where the dray jammed in the

doorway. Malcolm (by that time we were calling him "Mack" because Dad's

pronunciation of "Malcolm" sounded like ("Mah‑cum"), got a bit of a

scare from the wildest ride of his young life.

When I

started school in the fifth grade that year, I found we hadn't been

taught "Grammar" in Manitoba, and I had a bit of catching up to do.

They also had the "old red" Canadian history book, and just then "The

Prairie Provinces" became a text book.

During the holidays in 1911, I visited a farm in the Souris Valley where

they were haying. They drove the hayrack right into the loft, and

pitched hay to me which I spread around. By the second day I was pretty

homesick, but had discovered the relief a cold wash gave after a sweaty

morning's work. They had an automobile with headlights lit by gas

developed in a generator fastened to the running board. When I got home

I rushed to mother, threw my arms around her and she gave me a bear hug.

As

was the case in most prairie towns, a dependable water supply was a

constant problem, and that summer they were drilling for water, the

outfit consisting of a steam boiler which developed steam carried along

a bare metal pipe for a number of feet before it reached the steam

drill. One day Bill and I went to see how they worked. In walking

toward the drill, Bill sort of lost his balance and grabbed the

unprotected steam pipe getting his hand badly burned,

Dad

had a Sunday morning service in Glen Ewen. He had a clear strong voice

and led in the singing. Sometimes now when I hear some of the old songs

which were in the "Moody and Sankey" hymn book, I seem to hear his voice

joining in. After lunch on Sunday, he drove some thirty miles to

Newport, North Dakota, where he conducted an evening service, staying

there overnight and returning to Glen Ewen on Monday. In winter after

the long drive, he would come into the house tugging the icicles off his

moustache, and it was our duty to extinguish the charcoal "brick" which

was the source of heat in the "foot warmer."

One

spring day on the way home from school, I passed a small pond and near

it's edge I saw a snake with a frog in it's mouth ‑ so I made it a dual

execution (according to schoolboy lore a snake's tail wouldn't stop

twitching until after sundown). Kingbirds used to nest around the same

pond and if anyone approached the nest they set up an agitated racket,

in fact if one got too close to the nest they would "divebomb" and

strike one on the head.

While

in Glen Ewen I attended my first political meeting. That was the year

of the "Reciprocity Election" ‑ free trade with the U.S. ‑ which was

defeated. I am inclined to believe that if it had gone through, Western

Canada, through self‑interest, might have become an integral part of the

U.S.A. such a proposal having come to the front this year (1980) from

several Saskatchewan politicians who have financial interests in the

U.S.

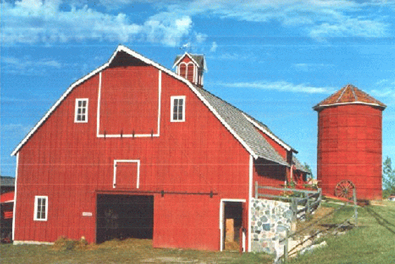

Pictures of

barn showing access by wagons to the loft.

In 1911

we moved to Newport, and while there dad was ordained as a Baptist

minister, and he acquired an "Oliver" typewriter, and a set of books

"The New International Encyclopedia" which I have ‑ can you imagine an

encyclopedia that doesn't make mention of aeroplanes We kept in touch

with Canadian affairs by subscribing to the Manitoba Free Press, one of

the news stories of that year (1912) telling of the breaking of the ice

bridge below Niagara Falls when several lives were lost.

At

Newport it was obvious there had been a great improvement in farming

operations ‑ big steam traction engines were replacing horses in many

areas, particularly in plowing. I recall seeing a big J. I. Case

tractor pulling a gang‑plow turning over twelve furrows at a time. They

didn't have to worry about leaving a headland ‑ it was virgin prairie

and there were no fences.

In

1912 we moved to Elk Point, South Dakota. One of the prized possessions

brought from Scotland was a large oval mirror and stand made of reddish

wood with a felt lined compartment for jewelry. (also brought from

Scotland were two pairs of brass candle sticks which Granny Sloan had

given to mother, and on arrival in Elgin mother gave Aunt Mary a choice

and she took the big pair ‑ I now have the small pair.) On the way from

Newport, by rail from Kenmare, N.D., to Minneapolis, Minn., by Soo line,

and then via Aberdeen, S.D., to Elk Point on the Milwaukee line, it was

my duty to take care of the mirror and I kept it in my charge until a

bed was assembled and bedclothes were spread out. I laid it face down

on the bed. Someone sat on the edge of the bed and the mirror slipped

and landed on the floor cracking it all the way across the middle.

In

the bustle of arranging furniture, etc., in a new home, Annie

disappeared. We searched the neighborhood without success, and mother

and dad were frantic about her being about in a strange place, when she

showed up ‑ she had been asleep in a small closet under a stairway in

the house, an out of the way place we hadn't noticed.

Case steam

traction engine with plough.

Case steam

traction engine on a threshing machine.

At

Elk Point we learned that corncobs were useful in a region where Eaton's

catalogues were unknown. I got a job in a nearby grocery store as an

errand boy ‑ have you ever been sent to locate a left handed monkey

wrench which had been loaned to another store? In school spelling bees

were a Friday afternoon event, and it was quite a thrill to spell a word

which the preceding scholar had missed, and moving up the line ahead of

those who missed it, and this procedure was followed until the head of

the line was reached, or the period ended, the person at the head of the

line when the period ended taking his place at the bottom of the line

the next time it was assembled.

But

tragedy struck in September, 1913 ‑ at the birth of her seventh child

there were complications, the baby was lost and mother was confined to

her bed. Every day when I came home from school I would go into her

bedroom, squat down on the floor and tell her what had occurred. One

evening after I had been in bed some time, I heard the telephone bell

ring, and a little later I heard someone come in. After a while dad

left the house, and I went downstairs where I saw the doctor, and he

sorrowfully shook his head. Mother's face was twitching and I leaned

over and kissed her, (she had succumbed, to an embolism (?) perhaps).

She was buried in Elk Point cemetery.

Dad

was left with six children ‑ fortunately help came from Mr. and Mrs.

Joel Webber, members of the church who had a farm a few miles out in the

country. They took Malcolm, Annie and Moffat. By this time Annie had

become known as "Dollie". One day Dad had been reading a story about

dolls to her and when he finished, she said to him "I'm your dollie,

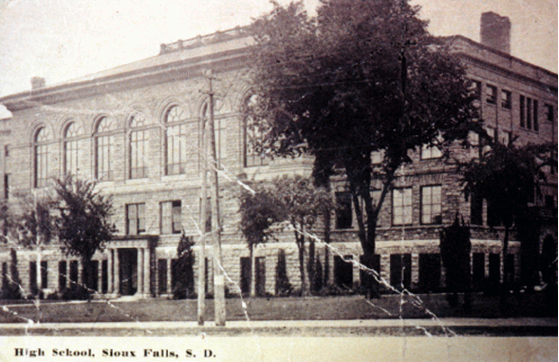

aren't I, daddy?" Bill and Bella went to the Oddfellows Orphanage at

Dell Rapids (Dad had been a member of the Elk Point lodge), and I went

to Sioux Falls to stay with Mr. and Mrs. Earl Pitcher (Mrs. Pitcher and

Mrs. Webber being sisters), Dad having arranged for me to attend Sioux

College which was under the auspices of the Baptists I had just

commenced my freshman year in Elk Point High School, and carried on in

that year at Sioux Falls. For pocket money I got a job delivering

papers on a route for the "Sioux Falls Herald". Just as I started the

route they commenced carrier collections, and they gave us 10% for

collecting outstanding subscriptions. The first week I collected over

$100 and the lad who had the route before me tried to get me to share it

with him, I told him he had been paid for his deliveries and he hadn't

assisted me in making collections, so I refused to share what I had

received.

When

Sioux Falls College year ended in the summer of 1914, I went to Sioux

City, Iowa, to join Dad, and I got a job in the packing room of a

wholesale grocery warehouse at $6.00 a week. After paying my board and

room where Dad lived, daily streetcar fares and lunches (soup, meat,

vegetables, pie and coffee $0.15) I had $0.95 for spending money and

Sunday collection.

Some

months earlier, Malcolm went to live with Judge and Mrs. J. L. Kennedy

in Sioux City, there being a family connection with the Webbers, and the

Kennedy's wanted a companion for their only son, Lloyd, who was

Malcolm's age.

When

school resumed that fall, I moved over to the Kennedy home (Mrs. Kennedy

had died in the meantime) where I looked after two riding horses and a

pony, and I attended Sioux City High School, taking Grade X.

The

Kennedys had been building a house in "The Heights" a new development,

and when it was completed that fall, we moved into it and the Judge

hired a housekeeper. Saturday afternoons, the two boys and I attended

the Orpheum Theatre, a vaudeville house. On one occasion, we were

sitting in a box seat, and one of the entertainers was a very good

violinist, and he would invite members of the audience to say something,

and he would imitate it on the violin. I don't recall how it happened,

but I had a siren whistle in my pocket, and at at opportune moment I

blew it. That brought the house down, even the violinist laughed.

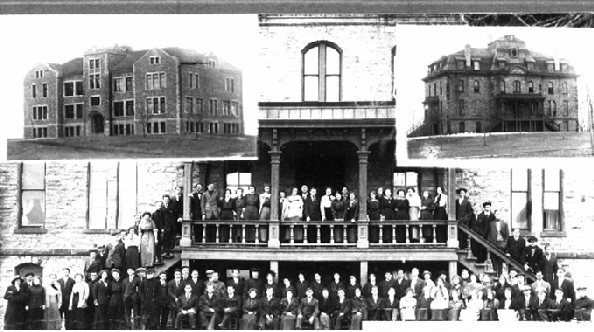

Sioux High

School, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Sioux Falls

College and some of the students.

Top

students (TMS under the ‘O’).

After

New Year's Day, 1915, the Judge and the two boys, with a colored

chauffeur who looked after the boys, went to California, and I was left

to shovel snow, coal, ashes, and to look after and exercise the two

riding horses and the pony, and I attended Sioux City Business College.

After being away for some weeks, the travelers returned, and the Judge

saddled his horse and went for a ride. When I got home the Judge told

me of his ride, and complained that I hadn't been looking after the

harness as the saddles and bridles I hadn't been using had a green

coating. (The stable was below the garage and was built into the side

of a hill. In the winter time, the door being closed, the atmosphere in

the stable was moist due to the presence of the animals.) I hadn't had

any instruction in the care of the harness, and I didn't like the

criticism, so on a Monday I took off for Winnipeg. The war had been on

for six months or so.

I kept

out of sight when the train stopped at Sheldon, Iowa, (Dad was there

then) and it was evening when it got to Minneapolis. I thought I might

stay in the station until the Winnipeg train left in the morning, but at

midnight I was turned out. I wandered along Hennepin Avenue for a

while, then decided to go into an upstairs hotel where the rates seemed

reasonable. The clerk showed me to a room, then asked if I wanted some

beer. When I declined, he asked if I wanted a woman and I refused. A

little later I heard him telling a woman in the hall about me.

The

next morning I boarded the train for Winnipeg, and on arrival at the

border that afternoon I was interrogated by the Immigration officer and

admitted I had only $5.00 in my possession. He seemed hesitant about

admitting me but a farmer seated nearby heard the conversation, and he

said he would give me a job on his farm which satisfied the Immigration

officer and he allowed me to proceed. After the train left Emerson the

farmer said, "OK kid, go where you want to."

After

arriving in Winnipeg, I visited the recruiting offices of the Winnipeg

Rifles, the Grenadiers, and the Cameron Highlanders which were on Main

Street near the C.N. station. While making these visits I met up with

several fellows who had the same purpose in mind. When we found these

regiments were not recruiting that day, we went to Portage & Sherbrook

where the Artillery had their office, with the same result, so we went

on to Minto Armories where the 44th Battalion was recruiting . I didn't

pass the medical when my eyes were tested.

One of

the fellows I had met told me not to worry but to come with him and he

would get me a job on a farm. The next day we took a train to Myrtle,

Man., and I got a job at $12 a month, to be increased to $20 when the

summer work started, but in the meantime there were the usual farm

chores to be done.

The

farmer stipulated that I must get in touch with my father, and I did.

Years later I learned that Judge Kennedy had got in touch with dad

several days after I left, and started to give him heck because he

hadn't notified the Judge I was with him. Dad, of course, told the

Judge that he hadn't the faintest notion where I might be. When summer

work started I was given charge of a four‑horse outfit and harrowing,

ploughing, and drove a binder when harvest was on.

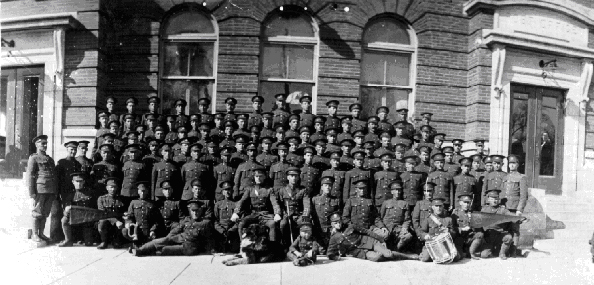

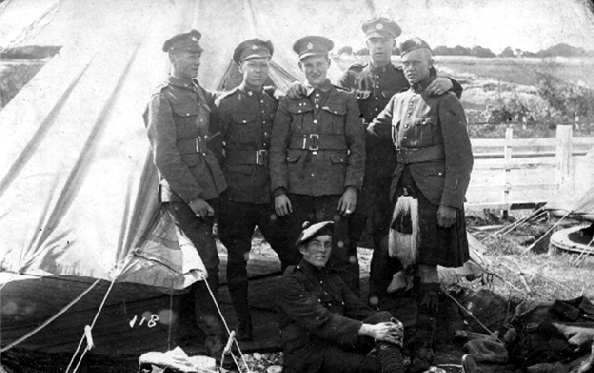

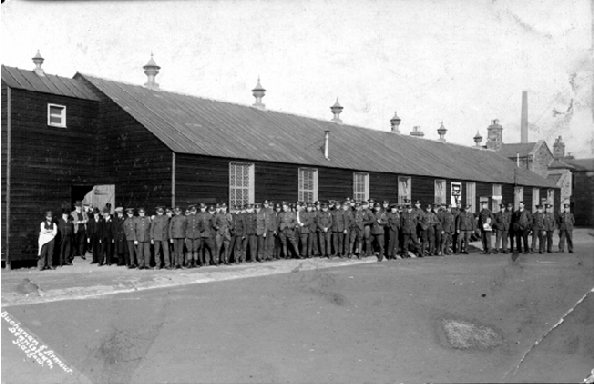

Carman

Detachment 222nd O.S. Battalion (on a postcard to Father).

TMS 4th row 2nd from right.

Left. Father and

I (about age 16). Centre: With two friends. Right:

Private Sutherland.

When

threshing commenced, I drove a grain wagon. As the threshing outfit was

moved a couple of times a day, it was necessary to "throw" the belt

which was then rolled up and stowed on the separator. On one occasion,

I took the notion that I would "throw" the belt, so I went over to it,

reached over and took hold of it when it was jerked out of my hand and I

went several feet before I could recover my balance. I tried again with

a like result. The engine was slowing down and I was near it's front

wheels and I determined that this time I was going to succeed and I took

a firm grip of the belt and was yanked off my feet and my arm shot up

between the belt and the flywheel and I was thrown against the big wheel

and my arm came free. I took several steps and the engine man asked me

how I was and I said "OK" and fell over in a faint. I was very lucky to

have escaped injury when my arm was caught between the belt and the

flywheel, as many persons had lost arms or been seriously injured in

similar occurrences. When I got up they showed me what I should have

done ‑ instead of catching hold of the belt, I should have put my arm

over it and bent it into a perpendicular position as it slipped by my

fore arm, and then pulled it toward me and it would run off the

flywheel.

In

the fall of 1915, I went to work for another farmer and when the first

farmer was paying me off he asserted that I had failed to skim the froth

off a pail of milk before giving it to the calf, and it had bloated up

and died several days after.

The

pay at the second farm was $10 a month during the winter, including

board and room, and I was to do chores, feed the animals, clean the

barns, etc., and the first job I was given to do was to attack an

accummulation of several years' manure, load it on to a spreader and

empty it on a nearby field ‑ that took several weeks. In February two

brothers with whom I was friendly, and I were in Roland, Man., when we

learned they were recruiting for a southern Manitoba battalion, so we

enlisted and were posted to the Carman detachment. When I told the

farmer we had enlisted, he agreed to let me go, but as he had to pay my

replacement $12 a month, he deducted from the money coming to me enough

to ensure that his costs for the winter help did not exceed $10 a month.

We

went into training at Carman, there being detachments at numerous

southern Manitoba towns, and when Camp Hughes opened that summer, a

special train called at the various points where detachments were in

training and took us to Camp Hughes where the 222nd Battalion was

assembled for the first time. Dad came up to Camp Hughes to see about

getting me out of the army as I was under age. I was paraded before Lt.

Col. Lightfoot who said he would give me a discharge if I wanted it, and

I told him I had enlisted in the army and wanted to stay, so Dad decided

to stay in Winnipeg where he became the pastor of the West Kildonan

Baptist Church.

Our

battalion was the last to leave Camp Hughes in the fall of 1916. There

had been over 40,000 of us in training there that year, all under

canvas. In the late fall, the tents were cold, so many of them became

heated by "coal oil" heaters, the occupants of a tent contributing to

pay for the heater and oil. After a cold night it wasn't unusual to see

grimy, even black faces in the morning indicating that the wick of the

heater had been turned up too high resulting in poor combustion causing

soot. When snow came, we were moved into the empty theatres.

We

went overseas on the S.S. "Olympic" in November, and went into camp at

Shoreham, Sussex, and within a few weeks may of the men went to France

where they reinforced the 1st C.M.R.s and the 44th Battalion. On Dec.

31st, those left in the 222nd marched to Seaford where we were

amalgamated with the remnants of the 196th (University) Battalion, to

form the 19th Reserve. In that Reserve there were quite a few under 19.

For service in France, we were moved to Witley to join the 128th, Moose

Jaw Battalion, in the organization of the "Fighting Fifth" Division but

as casualties were severe in France in the spring of 1917, the division

was broken up to supply reinforcements, and some of us found ourselves

in the Saskatchewan Regimental Reserve, where we became acquainted with

many men who had served in the 46th Battalion and were awaiting return

to that unit after discharge from hospital in England. The authorities

decided to gather all the under age troops into a Young Soldiers

Battalion, and we were sent to Bexhill, near Hastings, for training as

there was a special school there. At Bexhill we were again under

canvas, and after Reveille we were assembled, clad in greatcoats only,

and marched to Cooden Beach nearby to bathe in the English Channel in

the nude. Some local residents complained, and I understand the area

commandant, Brig.‑Gen. Critchel had an item in the local paper

commending the complainants on the quality of their field glasses

enabling them to discern anything which might be a cause for complaint.

We

returned to Bramshot that fall and were used on many occasions to

demonstrate to fresh arrivals from Canada how a smart unit performed

their drills. On one occasion we marched past King George V at one

hundred and sixty to the minute, our bugles were silent but the drummers

really went to town.

Speaking of bugles, they were rarely silent for long between "Reveille"

and "Lights Out" occasionally we heard "Long Reveille " but it was

usually the "Rouse', "Get out of bed, get out of bed" or the American "I

can't get 'em up, I can't get 'em up" and the buglers seemed to have

calls for everything. Each call was preceded by a few notes identifying

the unit making the call. After reveille they followed in quick

succession, "Sick" parade, cookhouse "Come and get it", "Come to the

cookhouse door" or "Pick ':em up, pick 'em up, hot potatoes", the half

hour dress, the quarter dress, the fall in, the "Come along," all having

to do with parades, the mail call "There's a letter from Lou", the

officers mess call "The officers wives get pudding and pies but we poor

beggars get skelly." The Orderly Room call for those who had to answer

for some transgression. "Retreat" at the end of the afternoon was a

formal call when everyone had to cease what he was doing and stand at

"Attention" while the flag was being lowered. Then there was the

"defaulters" call when those who had been "confined to barracks" had to

report to the guardroom every half hour for roll call.

At

Camp Hughes we had no trouble knowing when reveille would soon be

sounded as the next lines to ours was occupied by the 107th Batt. "Glen

Campbell's Scouts" many of them were Indian or of Indian extraction, and

their pipe band was out every morning tuning up their bagpipes or

tightening up their drums preparing to march through their lines with

pipes and drums playing as soon as reveille was sounded.

If we

happened to be near the cavalry or artillery units, the trumpet calls

were a contrast to the bugle calls. There was no mistaking "All who

are able, come down to the stable, and feed your horses and gallop away"

.

On board

ship. TMS middle row, right end.

Another

view of the ship.

One day

while we were at Bramshott, the Y.S.B. sent a detachment by train to

Aldershot where thousands of troops had been assembled to witness the

awards of valor, to those who had earned them, by His Majesty King

George V and Queen Mary. After some hours we boarded a train at

Aldershot, and had to change trains at Wigan(?) to catch one going in

the opposite direction. We boarded that train getting into the last

coach. When it stopped we found we were back in Aldershot ‑ the last

coach on the train we boarded was a "slip" coach which had been detached

from the train while in motion, switched on to the Aldershot line in

charge of a "Guard". It was rather late when we got back to Bramshott.

While

in England, I took the opportunity to visit Aunt Annie in Eccles (I

arrived at her home before the telegram, had been delivered, telling her

I was coming), and then went on to Howwood to visit Aunt Flora and her

family, finding her son Archie home on leave. I also visited the Easons

(I understand they later went to the antipodes). Then on to Dundee

where I arrived late in the evening and booked in at the Lamb's Hotel.

The following morning I made enquiry for Uncle Malcolm, finding him on

duty at the hotel. Nothing would do but that I should book out of the

hotel and go to his home. His eldest daughter Bella, a Territorial

nurse, was home on leave, and Katie was still at home. I also met two

of Dad's brothers and members of their families, one being the General

Foreman at the North British Railways Goods station, and the other had a

shop in Lochee, a suburb of Dundee.

Most

of us in the Y.S.B. were returned to our respective depots or reserves

towards the end of summer in 1918, and were sent to France. The group

from the Saskatchewan Regimental Reserve were sent to France to

reinforce the 46th Battalion, but after arrival at a staging station

there was a parade and we were informed volunteers were required for the

16th Batt. and volunteers were asked to step forward. We hadn't had any

contact with the 16th, and as we wished to stay together, none of our

group stepped forward, with the result that as many as were wanted were

counted off and detailed to go to that unit. As soon as that parade was

dismissed, we got together and decided as that was the way things went,

if another parade was called and volunteers were required, we would have

to step forward if we wanted to stay together. An hour or so later,

another parade was assembled and volunteers were asked for the 78th

Battalion, and our group stepped forward as one and we eventually joined

the 78th near Arras. On our way up from the staging area we travelled

in box cars marked "8 Cheveau 40 Hommes". Further progress was made on

foot and it seemed that we recognized and exchanged greetings with

someone in every unit we passed, having served with them in England.

The

first night we were bivouacked in an abandoned sugar factory and we

slept on stone floors, exchanging our rations which we had brought with

us. The next night we spent in what had been the cellar of a house, and

when I wakened in the morning I found I was looking up at the sky

through the chimney of a cellar fireplace. We were a short distance in

front and to the right of an artillery battery. We could see the flash

as the No.1 gun was fired, and as the No. 2 flashed, we heard the sound

of the discharge of the No.1 gun, and so all four guns followed each

other in that sequence.

As it

was getting along into the afternoon, I looked around to find something

to eat, and I started a fire in a small firebox adjacent to the house,

but as I stooped down, a blast of fire came out and engulfed me, burning

my face and hand and ruining my uniform. I was taken to the First Aid

station where my hands were bandaged and a dressing was put over my

face, holes having been cut for my eyes and mouth. I was dispatched to

a Casualty Clearing Station to be taken to hospital. While in the

C.C.S. they gave some lunch, and another casualty was asked to feed me.

He had some difficulty in finding my mouth through the hole in the

dressing, and just as he found it, he had to go places in a hurry ‑ he

was suffering from dysentery, and I didn't keep track of how often he

left me before I decided I didn't want any more. Late that evening, I

was taken to a hospital near St. Pol, but it was about 2 a.m. before I

finally reached the ward I was assigned to. Then as the beds came in

sight, I passed out, and they must have undressed me and put me to bed.

I was there about a week or so, finding it embarrassing to have to get

someone to do personal things for me. The dressing was taken off my

face, and if my face turned sideways the pillow slip or sheet stuck to

me, so I mostly lay on my back with my hands above my head.

In due

course I was evacuated to England, but the Channel crossing was very

rough and I had to walk with my elbows extended to combat the rocking of

the ship, then on the train as it went to Birkenhead and a hospital at

Thornton Hough, Lord Leverhume's estate. As I couldn't do anything for

myself, I stayed in bed reading, turning pages with my tongue, and being

fed by a nurse . In course of time my burns healed, but the first day

my hands were without dressings as I started to shuffle a pack of cards

blood blisters were raised on the palms of my hands. Being in "hospital

blues", blue trousers and jacket, white shirt and red tie, we were

allowed to travel on the ferries between Birkenhead and Liverpool, and

on the Liverpool "trams" without charge.

In the

course of time, I went to convalescent camp at "Bearwood", someone

else's estate, and one morning we were routed out of bed to go on parade

at 6 a.m. on a cold wet day. We were informed that at 11 a.m., that

day, November 11th, 1918, an armistice was coming into effect to end the

war. A few days later, those of us at Bearwood, and from other

convalescent camps found ourselves at Kimnel Park, near Rhyl in north

Wales awaiting transportation home. As most of us had quite a bit of

service, and were awaiting back pay and the leave usually given on

discharge from hospital, we weren't happy about it, and after a

demonstration at Headquarters, we were sent to our respective Reserves,

in my case the 11th, after being paid. I made my last visit to Eccles,

Howwood and Dundee, and returned to Canada on the S.S. "Baltic" in

February and was finally discharged at McGregor Barracks in Winnipeg,

Mar. 21, 1919.

Scene from

camp showing Bell tents in background. TMS 2nd from left.

A number of

post card scenes from Witley Camp in England

A few

fellows from camp. TMS 2nd from left. This is the front of

another post card.

This is

another post card stamped ‘Y.M.C.A. Institute, Maryhill Barracks

Glasgow’.

Dad

was then living in Thelmo Mansions on Burnell St., and had Bill, Bella

and Malcolm with him, as well as a housekeeper and her two children.

Shortly after my return and while wearing uniform, I went to Elk Point

where Dollie and Moffat were living with the Webbers, and brought them

to Winnipeg. Shortly afterwards we were asked to leave the Thelmo as

there were too many of us in the suite, so the Sutherlands moved to 742

St. Mathews Ave. During the summer the youngsters went out to Elgin to

visit Aunt Mary, and while there the whole family was quarantined

because of measles .

One

day Dad decided to make bread the way mother had done it. Several weeks

later I was in the basement checking the furnace and I saw a chunk of

coal on top of some trunks. I took it down and found it apparently was

a loaf of bread burned black as tar. I showed it to Dad and he admitted

that he had forgotten that the bread was baking and it had been badly

burned. We scraped away the charring and found the bread quite

palatable, but Dad didn't try to bake bread again.

Some

time after their trip to California, Judge Kennedy and the two boys went

on a trip to Yellowstone or Glacier National Park during which they did

a lot of horseback riding. Malcolm's horse was named "Buck" and it

seemed that Malcolm was urging or reproving him so often that the people

on the tour party began to call him "Buck", and that name stayed with

him. Some time later at Sioux City, Buck fell or was thrown off a horse

and his foot stuck in the stirrup and he was dragged along the ground,

and one of the horse's hooves struck him in the face.

After

being discharged from the army, I took a course at Success Business

College, and in the fall I got a job in the office of the Winnipeg City

Electrician,

In

1921, Dad married Jessie Gardner (five years my senior), and in 1922

Frank Mathieson arrived on the scene. We then moved to 553 Maryland,

where we had more room. After Isabel finished school, she enrolled for

training in Victoria General Hospital. When Buck finished, he got

casual work in Eatons.

In

1922, having become dissatisfied with the situation in the City

Electrician's office, I resigned and took up employment with the Dept.

of Investigation of the C.P.R.

When

Dollie finished school, there seemed to be some discussion about what

she should do, and I got the impression Dad and Jessie seemed to be

satisfied if she could find work as a domestic. I didn't like that, so

Buck, Dollie and I moved out and went into a small suite in the Wardlaw

Apts., on Osborne St. I arranged for Dollie to take a course at the

Success College, and enrolled Buck in a night school course in railroad

telegraphy, but I learned afterward he missed as many classes as he

attended. I also provided pocket money for Isabel as nurses in training

were not recompensed.

In

1927 there was a Royal Tour across Canada by the Prince of Wales and the

Duke of York, and their staffs, and Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and

his wife with their staffs. The tour was routed over the C.P.R.. and

our Chief, Brig. Gen. E. de B. Panet was appointed the official

representative of the Federal Government, and of the C.P.R. on the tour,

and I was selected to handle the secretarial duties. With Gen. Panet.

I boarded the R.M.S. "Empress of Australia" at Father Point in the Gulf

Or St. Lawrence, disembarking at Quebec City. From Quebec, we travelled

to Montreal up river on the Canada Steamship Lines S.S. St. Lawrence

with the other members of the C.P.R. party. Asst. to the Chief S. H.

Spry and three Investigators joined us for the rest of the tour. We

were tipped off that one of the American press correspondents had made a

bet that he would get an "exclusive" interview with H.R.H. on the trip.

The opportunity seemed to be opening up as the Princes stood admiring

the evening skyline as we neared Montreal, but the members of our party

closed him off, apologizing as we stepped on his toes. The tour

proceeded across Canada, the Baldwin party being disengaged at Banff for

their return, while we continued on to Victoria and wound up at Quebec

City.

As I

wasn't flush with money when I left Winnipeg, I hoped that Buck's wages

might pay for the groceries while I was away. On my return I was told

that there had been a water leak in the bathroom, and water had leaked

through the floor and the storekeeper downstairs had complained of

damage, and the leak had occurred when Buck leaned against the basin in

the bathroom, A day or so after I returned I answered a knock at the

door, and when I answered found it was the woman from the store

downstairs, who asked when her bill was going to be paid. I called

Dollie and learned that they had to charge for food they needed while I

was away, and I assured the woman that she would be paid without loss of

time. There was also some comment about the water damage, and I told

her it had occurred because of the poor condition of the plumbing and

the floor, matters I thought she should take up with the landlord. Many

months afterward I was told the damage had occurred when Buck stood on

the bathroom basin while he replaced a bulb in the ceiling light.

Shortly after the Wardlaw incident, we moved to the Highworth Apts., a

little further south on Osborne St. By this time Isabel had finished

her training at the Victoria and she moved in with us. Moffat also came

in, and after some negotiation he was started in school as an dependent

of mine. About this time Buck got a job as a cache‑keeper on the

Hudson's Bay line. When summer holidays came along, Moffat returned to

Dad. In the fall of 1927, with Isabel and Dollie, I moved to the Asa

Court at Langside & Broadway.

For

some years, I had been involved with snowshoe clubs and the Manitoba

Snowshoe Union, and I had become acquainted with Margaret Hughes who had

similar interests. We had often met at meetings and outings. One day I

asked her if she would take me to a Scottish show which was running at

the Walker Theatre. She said she would, and that was our first date. I

got tickets, met her, and we had a very pleasant evening. The Royal

Tour then intervened and we did not have another date for quite some

time. We met again at a New Year' s dance, and I had so many dances

with her that the chap she came with asked me if I was going to take her

home. We had various dates in January and by Valentine's Day she had

accepted my proposal and we were married on February 28th, 1928. We

were one of a group of eight couples who had been associated more or

less with snowshoe affairs for years, and with the assistance of one of

the couples we arranged that the others would be invited to a surprise

Party at the home where we were being married.

When we

were in a bedroom having a libation, one of the fellows said "Tom, you

don't seem very surprised to see us." "No," I replied, "Margaret and I

are going to be married tonight." There was a loud guffaw, and he said,

"Well, I'll call your bluff. Show us the marriage certificate." His

jaw dropped with surprise when I produced it.

We had

arranged for Dad to come into town and conduct the ceremony, which he

did. We were in a private home, and the owners had a Boston terrier

known as "Petey". When the soloist was singing "I love you truly,"

Petey joined in with his harmony. A little later Margaret and I managed

to slip away unnoticed, and we went to a nearby drugstore where I called

a taxi to take us to the Royal Alexandra Hotel where I had arranged for

a room with the proviso that our names would not be given to the

telephone operator. We were later told that when our absence was noted,

the fellows made frantic calls all over trying to locate us, without

success.

Margaret had been sharing a suite with two of her sisters, Birdie and

Hazel. and our marriage, of course, upset that arrangement. Dollie and

Isabel found other accommodation. Margaret sold a car she had, and we

began looking for a house and when our lease at Asa Court expired, we

moved to 537 Stiles St., which we had arranged to purchase. As we had

ample room there, Dollie moved in with us.

That

fall I was informed that I wag going to be appointed as an Acting

Investigator at the beginning of the year, with a sizeable increase in

salary, so we thought we were quite established when the promotion

materialized.

Pictures of TMS

A couple of

shots of Margaret Hughes

My

first assignment was to be on duty at the Royal Alexandra Hotel for the

New Year's Ball, which gave rise to the rumor that Margaret and I

weren't hitting it off as I had been at the Royal Alexandra Ball without

Margaret. One day when I came home for lunch, Dollie was there and

she wanted to see my handcuffs, and she learned their use by putting

them on her wrists. I went through the motions of looking for the key,

and said I couldn't find it and would have to go to the office for it.

Dollie was very much put out, and I left the house and crossed the

street as though I was going to the streetcar stop, but a few minutes

later I returned and relieved her distress by saying I had found the key

in another pocket.

Early

in 1930 we thought things were coming up rosy ‑ Margaret was going to

reveal her secret about the end of September, then in July I was told

that I was being transferred to Lethbridge in August. By explaining our

predicament and that Margaret was reluctant to change doctors, I got the

transfer postponed until November. Thomas Hughes arrived on September

27th, 1930 and my sister Mary Lou at Carnduff in July, 1931.

Buck

had returned to Winnipeg in the spring, and I was fortunate in getting

him appointed Constable in the summer establishment at Fort William.

While here, he got board and room at the home of Ruth's parents. He was

laid off at the end of the summer and enlisted in the R.C.M.P.

The

big market crash occurred that fall, and when we tried to rent the house

we couldn't get enough to meet the monthly payments. We moved to

Lethbridge in the middle of November ‑ did you ever travel for twenty

four hours in a stateroom on a train with a train‑sick woman and a six

weeks old baby? You quickly get acquainted with fundamentals. I had

been successful in getting a suite there, but when the gas stove we took

from Winnipeg was lit, the flame rose about two feet from the burner and

an adjustment had to be made to cut down the flame ‑ a contrast between

manufactured and natural gas. It was the first time Margaret had lived

in a town where she was a total stranger, and she had a hard time of it,

being cooped up in a suite with an infant while I was away. I was out of

town a lot as my territory extended from Shaunavon to Cardston, Medicine

Hat to Crowsnest, and Coutts to Calgary. We located one of her girlhood

friends and visited her on occasion. One night as we returned home she

said "Oh the elastic on my pants has broken" so in the darkness she

stepped out of them and I put them in my pocket.

One

day, having completed my work at Manyberries, I got a ride to Bow Island

with a school inspector, and then on the train to Medicine Hat to fill

in the time the train left that point for Lethbridge. While in Medicine

Hat I heard of the riot that day in Estevan where the miners were on

strike, and that Buck, a member of the R.C.M.P., had been pulled off his

horse and was injured. Through the courtesy of the telegraph operators

at Medicine Hat and Estevan I got a report on his condition before

leaving Medicine Hat.

The

Calgary Stampede imposed a lot of special duty on members of the

Department, particularly on the occasion of the Ball in the Hotel

Palliser, and the Investigators at Medicine Hat and Lethbridge were

called in to assist. On reporting at the office to ascertain what my

duties might be, I saw the duties drawn up by the Inspector assigned the

Medicine Hat to one floor, and I to one four floors away, and the

sentence "Acting Sergeant (so‑and‑so) will be in charge of all members

of the Department." The Medicine Hat Investigator was then in the

Inspector's office talking to him, and when he came out I went in and

found that the Inspector had gone out another door, and was gone for the

day. I later got him on the telephone and asked if there had been a

slip‑up in putting the Acting Sergeant in charge of all personnel of the

Department on duty at the Palliser that night and was informed that

there had not been a mistake, that was the way it was to be. I answered

that it was the way it would be, but if circumstances arose which I

thought an Investigator should handle, I would do that. Before going

off duty the next morning, affairs at the hotel having been without

incident (I saw one elderly man going down a corridor wrapped in a hotel

blanket to cover his nakedness). I put my complaint in writing and

left it for the Inspector before leaving for Lethbridge my tour of

special duty having been completed.

Some

weeks later, I was in Coleman when I heard that there had been some

thefts from a way car which was being worked that day between Aldersyde

and Lethbridge. I got back to Lethbridge about midnight, and caught the

northbound way freight which left about 6 a.m., and made enquiry at the

various points where the car had been worked getting particulars of the

missing goods. We arrived at Aldersyde late in the evening, and stayed

there awaiting the arrival of southbound trains for Lethbridge and

Macleod. The Lethbridge train set off two way cars for the Aldersyde

subdivision, which I had just covered, and the cars were spotted at the

south end of the yard, so before boarding the train I had been

travelling on to go to Calgary, I thought I had better take a look at

the two cars set off. The west side was OK, but as I started back up

the east side, I found a door open and heard some sounds out in a

field. It was a moonlight night, so I crept through the fence without

making a sound, and moved so that the moonlight was behind as I

approached a man who was busy going through merchandise he had taken

from the cars. I arrested him, handcuffed him, and took him to the

caboose I had been travelling in and gave the conductor my gun telling

him to use it if the man gave any trouble. I returned to pick up the

goods he had in the field, finding four or five other cartons along the

fence, and I picked up all the goods and took them to the caboose. As

the train moved away, the conductor signalled to stop at the station,

and I asked the operator to ask Calgary to have a car meet us at the

switch as I had a prisoner and a quantity of merchandise to be taken to

the office. This was done, and some days later the thief was sentenced

to six months' imprisonment.

This

was the first time anyone had been caught at Aldersyde although thefts

were believed to have occurred there on various occasions somewhere

along that line. The case stood me in good stead for some weeks later

Gen. Panet came up from Montreal, and the Assistant Chief from Winnipeg,

to deal with my complaint, a decision being made to move me from

Lethbridge, and I was transferred to Vancouver, where I had been on a

temporary two month assignment in 1930, when Margaret and I stayed at

the home of her paternal Aunt Nellie and her husband Sid Newell.

After

we left Winnipeg, our contacts with other members of the family became

sketchy ‑ no one would get a medal for being a correspondent.

At

Vancouver we got a suite in Engelsea Lodge, on Beach Ave. at the south

entrance to Stanley Park. We were in a ground floor suite facing on

Beach Ave., and Margaret and Hugh spent long hours watching the traffic

to and from Stanley Park. One night, shortly after we went to bed,

Margaret said "Some one in the next suite is snoring awfully loudly." I

told her I hadn't heard any snoring, so she said "Just wait." Seconds

later she said "There it is" I said, "That's not snoring ‑ it's the

Point Atkinson foghorn." Christmas lights were put on a tree inside

Stanley Park, and Hugh enjoyed watching them ‑ in fact one night when

looking at the lights Hugh came out with his first word ‑ "Pretty." I

had to go uptown to get a Christmas tree and walked back with it in a

drenching rain. As the weather improved I used to take him out for

walks and one day he did quite a bit of walking and running up and down

a small incline ‑ I was filled with remorse the next day when he had

difficulty in climbing up on a couch as his muscles stiffened up.

Margaret also took him into the Park and let him play in the puddles the

tide had left on rocks.

On one

occasion, knowing that I would be in Victoria for several days, I took

Margaret and Hugh along for the voyage. We went out Burrard Inlet, past

the Lion's Gate into English Bay, and as we swung around Point Grey into

the Gulf of Georgia, the ship began to rise and fall gently. We were