|

Thanks to Robert

Thomas for providing the information below on our Clans

WebBoard

In considering the succession to the

chiefship after the breakup of the clan, about the end of the

seventeenth century, it will be convenient to recall for a moment the

sons of Ian Mor. These in chronological order of their birth, were John,

Alexander, James, Robert, Thomas, and Angus, all of whom are amply

documented in the records of the period. Additionally, there was a child

named Donald who is never mentioned as a son of Ian Mor in any

contemporary document, but who is nevertheless held by tradition to have

been his youngest son.

Of the six elder sons, John and Robert, respectively the eldest and

fourth born, were killed in the skirmish at Drumgley in 1673, leaving no

issue. Alexander, the second son, who married an Ogilvie and had a son,

named Alexander, who traditionally, drowned in the Tay near Errol, while

yet unmarried in 1697. Furthermore, the senior Alexander had a daughter,

Elizabeth, who married Duncan Mackintosh, brother of Brigadier William

Mackintosh of Borlum of fifteen (1715) fame. This Alexander died in

October 1687, having been passed over in the succession to the Chiefship

by his younger brothers: James (the third son), who succeeded as 8th

Chief of the Clan in 1674. Likewise, Thomas (the fifth son), in turn

succeeded as 9th Chief in 1676. Neither of them apparently leaving male

issue. Therefore, upon the death of the latter the Chiefship of the

Clan, which as stated earlier, was not at the time considered worth the

trouble of claiming once the family lands had been lost and the clan

scattered, lay in the family of Angus, the sixth son of Ian Mor, of whom

we shall now treat.

As the actual dates of their respective deaths are not known, we cannot

say with any certainty whether Angus outlived his immediate elder

brother, Thomas, so becoming dejure chief of the clan, but there is some

tradition that he did so, and he is accordingly reckoned 10th chief. He

must have been born about 1647, and had been educated at St. Andrews

University, in the county of Fife, from which circumstance he is

frequently found referred to as Mr. Angus. Although apparently not

actually present at the skirmish at Drumgley, he had taken an active

part in the feud with Broughdearg, when he would have been in his early

twenties. He is found several times from 1668 onward as witness to bonds

and deeds by his brothers, and seems to have been last recorded as a

consenter to the alienation of the Forter lands by Thomas in 1681.

Family tradition has it that he afterwards settled at Collairnie, in the

Parish of Dunbog, in the north of Fife, anglicizing his Gaelic surname

of McComie (i.e. MacThomaidh) as MacThomas or Thomas, and marrying a

younger daughter of the already deceased laird of Denmylin, Sir James

Balfour, sometime Lord Lyon King of Arms to King Charles I, having by

her had two sons, Robert and John. The former, who was born in 1683, and

is said to have married an Antonia McColm from Kirkmichael, and is in

due course, found recorded in the Dunbog parish register at the baptisms

of his many children. From these entries may be seen the extreme

fluidity of the family surname at this time, and the difficulty

experienced in making a final choice. At the four baptisms occurring

between November 1720 and May 1726 Robert appears as Robert Thom. In

March 1728 he appears as Robert Thomas, in February 1730 as Robert Tam

in Cullarnie Ground and finally, from May 1732 to June 1734, as Robert

Thomas in Cullarnie. The surname Thomas was the one finally adopted, and

was used by the family for upwards of eighty years.

This Robert, reckoned eleventh Chief, subsequently removed from

Cullarnie and at his death on 29th April 1740, at the age of

fifty-seven, is described on his tombstone in Monimail churchyard as

tenant in Belhelvie. Belhelvie was a fine farm of considerable extent on

the south bank of the Tay River. It lay in the parish of Flisk in Fife.

Although he would have been of military age at the time of the fifteen,

as would his elder sons have been during the forty-five, they do not

appear to have become embroiled in the Jacobite rising, which added so

richly to the history of so many other clans; doubtless remembering only

too well the ruination of their family at the hands of the Stewart

Restoration Parliament during the latter half of the previous century.

Robert was succeeded in 1740 by his eldest son, David Thomas, reckoned

twelfth chief who, since he had been baptized on 29th July 1722, was

still a minor at the time. He died on 12th January 1751, aged

twenty-seven and apparently a bachelor, being succeeded by his younger

brother Henry. This Henry Thomas, thirteenth dejure chief of the clan

(baptized 17th, May 1724), continued to farm as tenant at Belhelvie,

like his father before him. He married twice; his first wife being

Margaret Miller, from Ceres, by whom he had four sons, William, Robert,

David and Henry. Margaret died on 27th, November 1765, aged 37, and a

little under two years later, on 14th, August 1767, Henry married

Elizabeth Reid, by whom he had a further son, George, born in 1768, who

was later to become a merchant in Dundee. Additionally, Henry and

Elizabeth had a daughter, Christian. Henry died on 3rd January 1797,

being succeeded at Belhelvie by his eldest son, William, fourteenth

dejure chief, as appears from the notice of marriage of the latter and

Helen Gardener, from the Muirhouse of Balhousie, Perth, two years later.

It seems that William afterwards became a merchant in St. Andrews. He

and his brothers all changed their surname from Thomas to Thoms, and it

is William Thoms that he is recorded in the entry relating to his death

at St. Andrews, on 15th, June 1843, apparently without issue. Lamentably

all too little is known regarding the fate of the remaining issue of

Henry Thomas's first marriage, but it has been assumed that by the time

of William's death it had become extinct, and the dormant chiefship thus

passed to the issue of the latter's half brother George.

William, 7th Chief of Clan Mackintosh and

8th Chief of Clan Chattan was the son and heir of Angus, 6th Chief of

Mackintosh, by his wife Eva, the heretix of Clan Chattan. He succeeded

his father in the chiefship of both clans in 1345, during the reign of

King David II, when he would have been about 50 years old. He married

twice, having children by both wives, as well as two concubines. We are

told that it was after the death of his first wife that William, (being

then very old) had two bastard sons, Adam and Sorald, by the second of

these concubines, whose name has not been preserved.

Adam, the elder of the two, grew up to be a man of considerable size (in

which he took after his father who, we are told, was of stature somewhat

higher than the ordinary, of a lean body and of great strength). For

this reason Adam was known as Adamh Mor (i.e. big Adam). He lived in

Atholl for a time, but later moved north again and settled at Garvamore,

in the Lagan district of Badenoch, a few miles west of Loch Crunachan,

on the south bank of the Spey. His descendants, known as the Sloichd

Adhamh Mhor Mhic uilleam (i.e. the tribe of big Adam, son of William),

are reckoned 5th of the nine tribes of Mackintosh, but it would be a

mistake to suppose that they were thought of from the outset as a

separate tribe. The household of a single Highland gentleman could not

by any stretch of the imagination be considered a clan, in the normally

accepted sense of that term. Therefore, Adam and his near descendants;

who it seems must have continued to dwell at Garvamore for some

generations; were obviously regarded by themselves and everyone else

simply as members of the main body of clan Mackintosh.

However, living as they did on the southern fringes of clan Chattan

country it would be reasonable to suppose that they were not much

troubled by the somewhat remote authority of the Mackintosh Chief.

Consequently, they would have acquired a certain independence, which

would have grown stronger as they gradually multiplied in numbers and

gathered a following. About the latter half of the fifteenth century

they emerged as a distinct clan under Thomas, the grandson or great

grandson of Adamh Mor, and from him they took the name of MacThomas.

Like so many others of his race, he too was a big man, and so was

affectionately named Tomaidh Mor (i.e. big Tommy).

This new found autonomy of the MacThomases is perhaps best understood if

it is seen as part of a general process of fragmentation, which appears

to have been taking place in Clan Mackintosh at that time. Clan Chattan

had by 1485 grown from a reasonably compact handful of clans into an

unwieldy confederation of no less than fourteen separate tribes, each

under its own chief. The larger the confederation grew the less

effective became the authority of the Macintosh, as paramount chief, to

bring to heel his own fractious Mackintosh cadets. During the chiefship

of Duncan, 11th of Mackintosh and 12th of Clan Chattan, which lasted

from 1464-96, several of them to become openly rebellious due to his

mild disposition. It was during this period that Rothiemurchus was made

over to Alisdair Ciar, founder of clan Shaw, whose following constituted

the second tribe of Mackintosh (from which the Farquharsons, or third

tribe of Macintosh, were to hive off during the following century).

Additionally, Donald Mhic Angus removed to Atholl with his following,

which are reckoned the fourth tribe of Mackintosh. Tomaidh Mor was

almost certainly another contemporary of Duncan and, although we have no

definite information as to when the MacThomases left Badenoch and

settled in Glenshee, it would seem natural that this too should have

occurred during the period of disintegration. The naming of the clan

after Tomaidh Mor would certainly be consistent with it being he who led

them across the mountains into that Perthshire glen, still more remote

from Mackintosh's authority, thus asserting their independence as a

separate clan, albeit acknowledging the over-chiefship of the

Mackintosh.

Just as we cannot say with any certitude when the clan first settled in

Glenshee, so we are somewhat uncertain as to the identity of the earlier

chiefs. Tomaidh Mor is of course regarded as the founder and first chief

of the clan, and his grandson Aye (i.e. Adam), who as Aye MacAne

MacThomas was a party to the Clan Chattan band of 2nd May 1543, is

considered third chief. Quite possibly the latter's predecessor was his

father, Ane or Iain (i.e. John), but of this we cannot be sure. Roughly

a generation later than Aye we find our first positive indication of a

chief dwelling in Glenshee, and from then on there is a reasonably

unbroken and well-documented line right down to the present time. In

those days, of course, the language of the clan was the Gaelic, and the

clan patronymic in that tongue was normally one or other of the

diminutives MacThomaidh (son of Tommy) or, less commonly, MacThom (son

of Tom). These are pronounced in English McHommy or McHom, so that we

generally find the early chiefs variously referred to as McComie or

McColme, or some such similar phonetic rendering.

The individual reckoned fourth chief, who may possibly have been the son

or nephew of Aye, referred to above, was Robert McComie or McColme, as

he is variously called. He is found as wadsetter, and later feur, of the

lands of the Thom (situated just to the east of Shee Water, opposite the

Spittal of Glenshee). Additionally, in 1595 he was one of several

notables, who at Invercauld, gave an heritable band of manrent to

Lachlan, 16th chief of Mackintosh and 17th of Clan Chattan, promising

faithfully to serve and defend him as their natty chief. It was probably

during Robert's chiefship that Clan MacThomas in Glenshee was mentioned

in the act of Parliament of 1587, as one to the Clannis that hes

Capitanes, Cheffis and Chiftanes quhom on they depends, and the

MacThomases were again mentioned in the act of 1594.

Chief Robert McComie and his neighbours seem to have been turbulent

characters. In 1594 together with Duncan McRitchie of Dalminzie, Robert

was called upon to answer before the Privy Council for seizing the lands

of the Spittal, which belonged to David Weymyss of that Ilk, and,

failing to do so, was declared a rebel. Three years later he was

involved in a potentially violent dispute with Duncan Robertson, in

Duncavane, and the same year the privy council sentenced him to be

incarcerated in Blackness castle together with several of his neighbours,

for defying an order of the courts with regard to tythes. Whether or not

these sentences were carried out seems doubtful.

Robert had married Barbara Rattray, presumed to have been a sister of

Alexander Rattray of Dalrulzion. He eventually seems to have been killed

by a band of Highland caterans, about 1600; two of his slayers: Donald

na Slogg and Finlay-a-Baleia, were caught by John Robertson, 6th baron

of Straloch (the MacThomases western neighbor), who hanged them from two

birch trees in the woods of Ennochdhu. Afterwards Robert's widow married

Alexander Farquharson, 1st of Allanquoich, whose younger brother John

Farquharson, 1st of Tullycairn, married Robert's only daughter Elspeth.

She was infeft in the Thom as heir to her father on 8th August 1616, and

transferred the feu to her stepfather the same day, with her husband's

consent. Although all this may have been perfectly fair and above board,

it would not be difficult to see in this episode a sordid conspiracy,

with the wretched girl's marriage as no more than a device to enable a

grasping step-father to possess himself the MacThomas lands aided by the

convenience of his brother and the infatuated widow of their former

owner. This may well have been the first act of Farquharson

aggrandizement at the expense of the MacThomases in Glenshee, whom they

were eventually to supplant and bring ruin.

From Clach A' Choilich: The magazine of the Clan MacThomas Society.

Clan MacThomas: Days of Glory

Thomas, a Gaelic speaking Highlander, known as Tomaidh Mor (i.e. Great

Tommy), from whom the clan takes its name, was a descendant of the Clan

Chattan Mackintoshes, his grandfather having been a son of William, 8th

Chief of Clan Chattan. Thomas lived in the 15th century, at a time when

the Clan Chattan Confederation had become large and unmanageable.

Therefore, he took his kinsmen and followers across the Grampians, from

Badenech to Glenshee where they settled and flourished being known as

McComie (phonetic form of the Gaelic MacThomaidh), McColm and McComas

(from MacThom and MacThomas). To the government in Edinburgh, they were

known as MacThomas and are so described in the Poll of the Clans in the

Acts of the Scottish parliament of 1587 and 1595. MacThomas remains the

official name of the clan to this day, notwithstanding the fact that few

of its members have ever actually been named MacThomas.

The early chiefs of the Clan MacThomas were seated at the Thom, on the

east bank of the Shee Water opposite the Spittle of Glenshee, the site

is thought to be that of the tomb of the legendary Diarmid of Fingalian

saga, with which Glenshee has so many associations. When the 4th Chief,

Robert McComie of the Thom, was murdered (c. 1600), the chiefship passed

to his brother, John McComie of Finegand. Therefore, the seat of the

chiefs was moved to Finegand about three miles down the glen. Finegand

is a corruption of the Gaelic "Feith nan Ceann" meaning

"burn of the heads." This refers to the time when some tax

collectors were attacked by some clansman, who cut off their heads and

threw them in a nearby burn. By now, the MacThomases had acquired a lot

of property in the glen and houses were well established at Kerrow and

Benzian with shielings up Glen Beag. The time was spent breeding cattle

and fighting off those seeking to rustle them, one such skirmish, in

1606, being remembered as the Battle of the Cairnwell.

The 7th Chief was John McComie (Iain Mor). His deeds passed into the

folklore of Perthshire and Angus, wherein he is generally known as

"McComie Mor." The legends surrounding this Highland hero

abound. In defense of a poor widow, he single handedly put to flight

some tax collectors, he killed the Earl of Atholl's champion swordsman,

he slew a man that had insulted his wife, he fought his son in disguise

to test his courage, he overcame a ferocious bull with his bare hands,

and he said to have been familiar with the supernatural. Today, a large

stone at the head of Glen Prosen is known as McComie Mor's Putting

Stone, a nearby spring as McComie Mor's Well, and at the top of Glen

Beannie a rock shaped like a seat is called McComie Mor's Chair.

Iain Mor joined Montrose at Dundee in 1644 and fought for the King's

cause throughout the campaign. He personally captured Sir William Forbes

of Craigivar, but after the defeat at Philiphaugh he withdrew from the

struggle and devoted his energies to cattle raising. During this time

the clan extended their lands and influence into Glen Prosen and

Strathardle and Iain Mor purchased the Barony of Forter in Glenisla from

Lord Airlie. Forter Castle had been burned eleven years earlier, as

recounted in the ballad "The Bonnie House of Airlie." Thus,

Iain Mor made his home at Crandart, two miles north of the castle. The

government of Cromwell won Iain Mor's admiration for the prosperity that

it brought to Scotland. However, this soured his relationship with

Airlie and upon the restoration of Charles II in 1660 he found himself

in trouble with Parliarment. He was fined heavily and at Airlie's

instigation a lawsuit decreed that the Canlochan Forest, part of the

Forter estate, belonged to Airlie. Iain Mor refused to recognize this

and continued to pasture his cattle on the disputed land, which Airlie

had rented to Robert Farquharson of Broughdearg. Broughdearg was Iain

Mor's cousin but the dispute over the forest led to a bitter feud that

culminated in a skirmish at Drumgley, just west of Forfar. At a spot

known as McComie's Field, Broughdearg was slain on January 28, 1673,

along with two of Iain Mor's sons. The fine, feud, and crippling lawsuit

that followed ruined the MacThomases and following Iain Mor's death his

remaining sons were forced to sell their lands.

The MacThomas Chief is mentioned in Government proclaimation in 1678 and

1681 but the clan was now drifting apart with some going into the Tay

valley and changing their name to Thomson. Others went into Angus and

Fife where they became Thomas, Thom, or Thoms. The 10th Chief, Angus,

took the surname Thomas and later Thoms. He settled in northern Fife

where his family thrived as successful farmers. Next they moved to

Dundee and became prosperous merchants at the beginning of the

eighteenth century. Thus, they purchased the estate of Aberlemno near

Forfar. Still others of the clan moved into Aberdeenshire, where the

name became corrupted to McCombie as well as Anglicized forms of Thom

and Thomson. In Aberdeenshire, the principle MacThomas family was the

McCombie's of Easterskene, who were descendants of the youngest of Iain

Mor's sons. It is one of their party, William McCombie of Tillyfour, M.P.

for South Aberdeenshire at the end of the last century, who is regarded

as the father of the world famous breed of cattle.

Patrick Hunter MacThomas Thoms of Aberlemno, 15th Chief, was Provost of

Dundee from 1847 to 1853. His hire, the eccentric George Hunter

MacThomas Thoms, advocate, bon vivant, and philanthropist, became

sheriff of Caithness, Orkney and Shetland in 1870. During his lifetime,

he donated large sums to St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh. Upon his

death in 1903 he willed his vast fortune to St. Magnus Cathedral in

Kirkwall, including the Aberlemno estate. Having lost Aberlemno, the

chiefly family assumed the surname MacThomas. Years later, in 1967, the

latter's great-nephew was once again officially recognized by the Lyon

Court by the historic designator "The MacThomas of Finegand."

Patrick MacThomas of Finegand, 18th Chief, married Elizabeth Clayhill-Henderson

of Invergowrie in 1941. It was during his lifetime, in 1954, that the

Clan MacThomas Society of Scotland was founded. He died in 1970 and was

succeeded by his only son, Andrew, the 19th Chief, who is called in the

Gaelic MacThomaidh Mhor (pronounced McHomy Vor).

The Great MacThomas-MacTavish-Thomson

Mixup

The following article was printed in the

fifth "Clach A' Choilich," the magazine of the Clan MacThomas

Society. The material was researdhed and written by the late Mr. Roger

F. Pye, our former Clan Historian and Vice President.

THE GREAT MACTHOMAS-MACTAVISH-THOMSON MIXUP

"On page 17 of the first issue of this magazine I started off the

series "The Clan and its Septs" with a very brief note on the

name MacThomas itself, from which it emerge that the name was a very

rare one and that only two or three examples were known to me. On the

same page, under the title "A Warning" I mentioned the

extraordinary confusion between the MacThomases and the MacTavishes, and

I promised to revert to the matter in due course. This I am now

doing."

Within the last two years a family named MacThomas has been discovered

in California, although unhappily it has not been possible to induce

them to join our Clan Society. More important, however, has been the

discovery, arising out of the correspondence regarding the McComie

Andersons of Loch Tayside, in Breadalbane, that there were a number of

people named MacThomas, living around the western end of loch Tay,

during the first quarter of the 17th century. That these MacThomases

should have used the alternative form of McComie is no more than we

should have expected, and simply repeats what happened in Glenshee

itself. The Shee being one of the minor tributaries of the Tay, it is

not in the least surprising that some member or members of the clan

should have migrated down into the Tay valley, and thence made their way

up to Loch Tay at its upper end.

What is both surprising and disconcerting is that in close proximity of

these 17th century Breadalbane MacThomases we find a considerable number

of MacTavishes. Now the name MacTavish, like MacThomas, simply means

"son of Thomas," with the difference that it is taken from the

braid Scots form Tamas, rather than from the form Thomas. We have always

(and rightly) insisted that the MacThomases and MacTavishes had nothing

to do with one another and were utterly different and distinct clans.

The former deriving from the MacKintoshes and dwelling in Glenshee, on

the Perthshire Angus border and the latter dwelling in Argyll as

dependents, and possibly descendants, of the Campbell Lords of that

country. What then are we to make of these Breadalbane MacTavishes? Were

they really MacThomases, or vice versa? Or was Loch Tay perhaps, as in

fact seems most likely (and as a glance at the physical map of Scotland

will confirm), the halfway house between MacThomas and MacTavish

countries, into which small groups of both clans, one from the East and

the other from the West, had migrated and settled?

Certainly the confusion between MacThomases and MacTavishes has been one

of the major handicaps which our Clan Society has had to face, for all

the popular text books on clans and tartans, even when published under

the auspices of presumed authorities who might be expected to have

expert knowledge of the subject, have simply lumped the two together,

and the Thomsons in with them, as though they were all one, and

MacThomas and Thomson are both treated as if they were all part of the

tiny Clan MacTavish. The fact that there are MacThomases of MacKintosh

derivation is occasionally recognized, however, to the extent that

MacThomas is sometimes listed as a sept of Campbell of Argyll (i.e. the

superiors and possible progenitors of the MacTavishes) or of MacKintosh.

The same books normally allocate all the Thomsons to Campbell of Argyll

(presumably through a MacTavish origin), despite the fact that Thomson

is one of the most common surnames in Scotland and accounts for rather

more than one percent of the entire population. The same tartan is

attributed to all, and the unwary would-be purchaser of MacThomas tartan

is quite likely to find himself sold the MacTavish/Thomson sett.

This almost unbelievable confusion of identity, which of course has

largely arisen as a consequence of the three century long eclipse of

Clan MacThomas, has led to a very serious loss of the latter's

credibility, so that amongst the general public there is more often than

not an almost complete disbelief that such a clan as MacThomas can ever

have existed. To those who have read the five issues of this magazine it

will, I hope, be obvious and beyond doubt that ours is a perfectly

genuine and ancient Highland clan, but to the public at large the mere

mention of Clan MacThomas is calculated to produce grins of incredulity.

Who is to blame them when the popular text books and all tartan mongers

conspire to deprive us of that distinct identity which is ours by

historic right?

Until this has been corrected so as to enable the causal seeker after

information to find the clan referred to in the popular text books in

its proper historical context and with in its own particular tartan, the

Clan Society can never hope to flourish. The first and most urgent

concern of the Council should be to allow the authors, publishers, and

shopkeepers no rest until the books and lists of names and tartans

concerned have been suitably amended to include MacThomas as a clan in

its own right with its own distinctive tartan. To go no as we are, in

the face of almost total public ignorance and misinformation, is to

court eventual failure, and there is nothing so vital to our survival as

that we should go to the root of the trouble without further

delay."

As can be seen from that above quoted material it is difficult, to say

the least, for a once dormant clan to rise up and reclaim its former

glory. Therefore, I encourage my friends with Thomas derived surnames to

continue to research their own individual genealogies and determine as

best as possible their true and rightful place among the various clans

that claim them as septs. Again I stress the importance of the

historical physical location of one's ancestor. It makes a great deal of

difference to know if one's ancestor was from an area well known for its

association with a particular clan or if he was from one of the areas,

as noted above, where various clans migrated and intermingled together.

Likewise, I must reiterate that Clan MacThomas is completely separate

and distinct from both clans Campbell and MacTavish. We trace our line

of descent back to "Great Thomas" a grandson of William

MacKintosh the 8th Chief of Clan Chattan. I hope this information helps

those with the Thom, Thomas, Thomason, and Thoms surnames.

God Speed,

Robert

E. Thomas

NC State Representative

Clan MacThomas Society of Scotland

CLAN MACTHOMAS: THE LAIRDS OF FORTER

by Roger F. Pye

In 1651, the same year that he acquired Forter, Ian Mor also purchased

from George Ogilvie the liferent of the lands of Wester Dalnacabock, in

Winnygil. Approximately five years later he bought the liferent of

three-eighths of the lands of Wester Inverharity, both of which had

previously been in possession of the Campbells of Easter Denhead, to

which family Iain Mor's wife Elspeth belonged. It is not known where

Iain Mor dwelt during this period, because Forter Castle had been burnt

and gutted by Argyll eleven years before he bought the property.

However, in 1660 he built himself a "ha'-house" at Crandart,

about a mile and-a-half to the north of the castle, and this became the

seat of his family.

The contract relating to the purchase of the Forter property had

specifically excluded the lands to the East of the Isla, as well as the

Forest of Canlochan, lying on the West side of the stream between the

burn of that name and the burn and corrie of Glas. However,

notwithstanding this exclusion, Iain Mor eventually obtained possession

of the Canlochan lands on wadset, together with royal letter of free

forestry. Additionally, his prosperity may be gauged from the fact that

in about 1660 he is stated to have been pasturing there no less than

twenty milch kine and more than one hundred oxen, besides a number of

horses.

From the very beginning of his possession of Forter, however, Iain Mor

had been falling out increasingly with his neighbours and erstwhile

friends and comrades in arms. The origin of these differences was

political, for in 1651 (the year that he bought Forter) Cromwell had

smashed the Scottish army of the Covenant at Worcester and then, almost

without opposition, had occupied the whole of Scotland, from the border

to the Pentland Frith, by the end of the same year. English garrisons

had been set up in all the main towns and the country was ruled by

English Commissioners, almost as an English province, to the impotent

rage of the Scots, both

Royalists and Covenanters alike. What made this English occupation all

the more intolerable, however, was the fact that the Scots found

themselves governed better than they had ever been before; law and order

was complete, trade flourished, and the country enjoyed peace and

prosperity such as had not existed within living memory. An intelligent

and just man, Iain Mor, who was himself prospering thanks to the

improved situation, eventually became convinced that there was much to

be said for a form of government resulting in so much common good, and

accordingly cooperated with it so far as he was able.

This was too much for his fiercely nationalistic neighbours, the

Ogilvies, who might have been able to forgive him had he joined the

Covenant, but never for accepting the English. Thus, Lord Airlie, who

originally had probably been quite content to let his land go to his

father's old comrade, Iain Mor, now became determined to recover, by

hook or by crook, whatever he could from one whom, had he lived in the

present generation (c. 1970), he would doubtless have stigmatized as

"that damned Quisling!" Accordingly, within a year of the

Restoration of King Charles II in 1669, he had induced Royal Parliament

to pass an Act of Decreet in his favour, restoring to him the Canlochan

Forest and Letters of free forestry. Shortly after this, no doubt at

Lord Airlie's instigation, Iain Mor found himself amongst those exempted

from the Act of Indemnity passed by the same Parliament in 1662, and

accordingly had to pay a fine of 1,600 pounds Scots for his

collaboration with the Roundheads. However, Lord Airlie had not counted

on the stubborn obstinacy of Iain Mor, who simply ignored the Act of

Parliament that he considered unjust and continued to pasture his beasts

as before in the disputed territory. Accordingly, in 1664, Lord Airlie

brought a further action against him for contravention, presumably with

as little practical effect as before.

In spite of these tribulations, Iain Mor remained unbowed, and in August

1665 he and his followers unexpectedly accompanied Lachlan, 19th of

Mackintosh, on an expedition into Lochaber against the Camerons, which

finally settled bloodlessly the three hundred year old feud between that

clan and Clan Chattan.

About this time Lord Airlie let the grazings of Canlochan Forest to Iain

Mor's second cousin, Robert Farquharson of Broughdearg, who thus also

became embroiled in the dispute regarding these lands. There is no

reason to suppose that the cousins had not been on good terms prior to

this. Indeed there is a tradition that Broughdearg was engaged to Iain

Mor's daughter. However, the quarrel between them was evidently coming

to the boil by 10th November 1666, when The Mackintosh wrote to Lord

MacDonald and Aros that he had "to go on Thursday morning to

Glenylea to settle two near kinsmen who are like to fall out very

foully." It would seem reasonable to suppose that the causus belli

was that Iain Mor continued to insist upon pasturing his beasts on the

grazings let to Broughdearg. If this was so it would have been very

understandable if Broughdearg had broken off his engagement in his

exasperation at the old man's stubbornness.

Over the next two years the quarrel grew into a serious feud, and on 1st

January 1669 Broughdearg, with fifty or sixty armed men, surprised the

old chief outside his house at daybreak. They carried him back to

Glenshee, where they held him until the following day, when his sons

gave a bond for 1,700 merks for his release. Four months later, on 14th

May, a party of thirty eight of Broughdearg's following raided

Kirkhillocks, at the southern end of the MacThomas Glenisla territory,

and sowed and harrowed the land, thus destroying the crops sowed earlier

by Iain Mor's fourth son, Robert.

In the summer of the following year, Alexander and James, the second and

third sons of Iain Mor, with three followers, came across Broughdearg

himself in the disputed Canlochan Forest, and he had to flee for his

life; the MacThomases seizing two of his horses. On another occasion,

when a party of his clansmen had allowed Broughdearg to escape from them

after an encounter in Glenarmie, the old chief had cursed them roundly

"for not taking from him ane legg, ane arme or his lyff."

In retaliation the Farquharsons seized some MacThomas cattle in the

disputed territory in 1672. Whereupon Iain Mor "persewed a spulzie"

against Broughdearg before the Sheriff of Forfar and got letters of

caption against him. Broughdearg refused to give himself up to the burgh

messenger sent to arrest him, saying that "no man should take him

alive," but on 28th January 1673, accompanied by some seventeen of

his followers, he went into Forfar "for his own defense of the said

pursuit." The MacThomases, learning of this journey, also proceeded

to Forfar, but the Farquharsons seem to have got wind of this and turned

back for home.

The MacThomases, pausing only to collect the burgh messenger in Forfar

in order to legalize their position, hastened after them and caught up

with them near Drumgley, a mile or two to the West of Forfar, where they

called upon Broughdearg to give himself up. This he refused to do, and

in their efforts to apprehend him Robert, Iain Mor's fourth son, was

shot outright, while his eldest brother John was dirked to death after

falling wounded from the same discharge. The Farquharsons then made a

dash for it, but Broughdearg was shot dead before he could get away, and

his brother John was so severely wounded that he was expected to die.

The Farquharsons quickly made representations to the Privy Council, who

appointed a Commission to apprehend the MacThomases concerned. Iain Mor

with his sons Thomas and Angus (who seem not to have been present at the

skirmish) soon afterwards presented themselves, but were eventually

allowed to go home upon giving 5000 merks each as security. Alexander

and James and three followers (who had been present) failed to appear

and were declared fugitives. They eventually submitted a year later, and

all five were tried by jury for murder on 10th June 1674, and acquitted.

Earlier the same year, however, Iain Mor, already an old man, had died.

He was succeeded as eighth Chief by his third son James, who having with

his immediate elder brother been on trial for his life, now had to raise

the money to pay the very heavy costs of the proceedings. Such heavy

costs may be imagined from the fact that the two leading Counsel for the

MacThomases were no lesser personages than Sir George Lockhart, who had

been Lord Advocate, and Sir George Mackenzie, who was about to become

so. To do this the unfortunate new chief had no option but to raise

bonds on his lands. He only survived his father by two years, being

succeeded in the spring of 1676 by his brother Thomas, who thus became

ninth Chief.

This Thomas, fifth son of Iain Mor, had been a merchant in Montrose at

least as early as 1670, and may well have been associated with his

father in his cattle business. His absence in Montrose appears to have

kept him out of the feud with Broughdearg. He was served heir-of-line to

his predecessor in 1677. Likewise, he is mentioned in the Proclamations

of 1678 and 1681 amongst the subordinate Chiefs required to give bond

for the good behaviour of their followers. In the latter year he was

also included in the Royal Commission of Fire and Sword granted to

Lachlan, 19th of Mackintosh and 20th of Clan Chattan, against the

MacDonnells in Keppoch. This commission was never put into effect. In

1681, with the consent of his brothers, Alexander and Angus, he formally

disposed of the Forter estate in favour of David, Lord Ogilvie. However,

he retained a wadset of Burnside until 1694.

What became of him after this we do not know. No trace has been found of

his death, and it has been suggested that he left no family. The present

writer believes; however, that he had a daughter Isabella, who married

Donald Ramsay of Cronaherrich, once a MacThomas shieling in Glenbeg, and

who was known in the Gaelic for her beauty as Iseabal Bain, i.e. Fair

Isabella.

The clan, which had for some time been drifting apart, now finally broke

up completely and ceased to exist as an organized group. With its

dispersal and the loss of their lands the chiefship became an empty

title, not worth the trouble of claiming, and upon the death of Thomas,

ninth and last of the old chiefs, was allowed to fall dormant. Thus Clan

MacThomas disappeared into almost complete oblivion for well over an

hundred years, until the great romantic revival of the early nineteenth

century started to reawaken interest in it.

R. F. P.

CLAN MACTHOMAS: THE LAIRDS OF FINEGAND

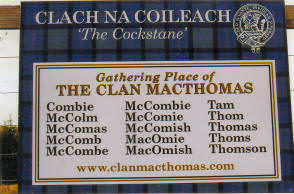

We have seen how the Cockstane came to be named in consequence of the

resistance strewn by Iain Mor to the kain-gathers of the Earl of Atholl

(1), and it is curious to note that Finegand itself, for so long the

seat of the MacThomas chiefs, also derived its name from an earlier and

bloodier encounter with those same ever unpopular tax-collectors. It

seems likely that this earlier affair took place before the MacThomases

had settled in Glenshee, and so incensed were the glensmen on this

occasion that not only did they slay their oppressors, but afterwards

cut off their heads and flung them into the near-by burn, which duly

became known in the Gaelic as Feith nan Ceann, meaning

John and Janet had (probably with other children) (3) a son, also named

John, and on 7th September 1568 the three of them had a feu charter from

Thomas Scott of Pitgorno of the four merk lands of Finegand and the

shelling of Gormel, in Glenbeg (4). The MacThomases had clearly already

been in occupation for some time, however; for in the charter they are

stated to have been tenants and occupiers of the lands in question ab

antiquo. Three years later they had a new charter of the same lands with

the addition, in favour of the younger John, of the lands and shelling

of Cronaherrich (5), which lay in Glenbeg immediately to the south of

the Gormel shelling; both lying on the eastern side of the stream. About

1582 the younger John married Janet, daughter of William Farquharson,

who was the eldest son of the Farquharson hero Finla Mor, and in

November that year they had a charter of three-fourths of the town and

lands of Binzean Mor (6), lying about a mile downstream from the Spittal.

When the fourth Chief was murdered by catarans about the turn of the

century, his brother, John of Finegand, the Elder, traditionally

succeeded him as fifth Chief. It is evident that the catarans were

giving continuous trouble about this time, and in 1602 the biggest raid

ever took place, when two hundred catarans from Glen Garry (7), said to

have been principally MacGregors and Cattanachs; rounded up no fewer

than 2,700 head of cattle and 1OO horses from Glenshee, Glenisla and

Strathardle, which was precisely the area over which the MacThomases

were spread. The robbers were hotly pursued and caught near the Devil's

Elbow, as they drove the beasts up the hill road out of the glen A

furious fight, afterwards known as the Battle of the Cairnwell, took

place and the catarans were eventually defeated, but not before they had

first butchered most of the cattle out of pure spite (8). This raid must

have caused very great financial loss to the MacThomases, but one of the

main victims was Finegand's brother-in-law, Rattray of Dalrulzion, who

also had grazing lands in Glenshee and Glenbeg (9), and who was

virtually ruined (10).

John McComie of Finegand the Younger is believed to have predeceased his

father, and so it was his son, Alexander, who succeeded his grandfather

as sixth Chief, some time before the end of 1606 (11). This Alexander

married Margaret Small, who was presumably of the family of Small of

Dirnanean, at the top of Strathardle, and on 5th December 1606 they had

sasin of the town and lands of Corrydon (12), about half-a-mile upstream

from Finegand. It was during his chiefship that the feu of the old

MacThomas lands of the Thom was finally transferred to Alexander

Farquharson of Allanaquoich on 8th August 1616, as previously noticed

(l3), and it may be possible to explain his failure to take any

effective action to prevent this alienation of the family property by

the fact that, through his Farquharson mother, he was himself a

reasonably close kinsman to Allanaquoich. Alexander was dead by 1637 and

was succeeded by his son John; seventh and greatest of the MacThomas

chiefs; better known to us as Iain Mor. We first come accross him as

party to an agreement with Rattray of Dalrulzion regarding the sheilings

in Glenbeg, signed on 18th May 1637 (14), and in 1644 he had wadset of

the lands of Carrow, or Kerrow (l5), on the East bank of the Shee, about

half-a-mile South of the Thom.

In the year before this last acquisition the Scottish Parliament,

dominated by the Covenanters (16), had determined to go to the

assistance of the English Parliamentarians, then at war against their

King, Charles I, and in 1644 the Marquis of Montrose, in the hope of

reconquering Scotland for the King, sent round the Firey Cross in order

to raise the Highland clans, several of which responded nobly to the

call. Amongst those who rallied to Montrose was Iain Mor (l7) with his

followers, who joined the Royalist army at Dundee a few days after the

Marquis's initial victory at Tippermuir (1st Sept. 1644) (18).

Thereafter he served throughout Montrose's glorious campaign, with its

brilliant victories at Aberdeen (where Iain Mor is traditionally

credited with personally capturing Sir William Forbes of Craigievar)

(19), Inverlochy, Dundee, Auldearn, Alford and Kilsyth. On I3th

September 1645, however, the shattering defeat at Philiphaugh put an end

to the hopes of the Scottish Royalists, who laid down their arms after

terms had been agreed providing for the safety of the lives and property

of most of them (20). Although he had fought loyally and bravely for the

King, Iain Mor, unlike his Ogilvie and Farquharson neighbours, now

withdrew entirely from the contest, and devoted his considerable

energies wholeheartedly to the more remunerative business of cattle

raising on his Glenshee lands

In 1668 he had a feu charter of the fourth part of Binzean Mor (21),

thus giving him possession of the whole, and this purchase brought the

property of the MacThomas chiefs in Glenshee to its greatest extent. It

should be understood that Glenshee was never solely the preserve of the

MacThomases. So far as can be ascertained the chiefs never possessed

lands further South than the road to Glenisla, and even in the upper

part of the glen there were groups of MacRitchies, Mackenzies and

Farquharsons between whom and the MacThomases land changed hands fairly

frequently, so that at one time one family would predominate; at another

another. Generally speaking, the lands of the MacThomas chiefs occupied

most of the West bank of the Shee, from about the Cockstane in the South

to the Spittal in the North together with the greater part of Glenbeg.

The East bank of the Shee was occupied by Farquharsons, Mackenzies and

MacRitchies, and the latter also occupied the extreme North Western end

of Glenshee at Dalmunzie. Apart from the property of the chiefs,

however, there were many MacThomas clansmen scattered over what are

generally considered as Spalding and Rattray lands further down the

glen, and westward into Strathardle.

By 1651 Iain Mor had prospered so greatly as a cattle dealer that he was

looking around for more extensive pasture lands and it was in that year

that he acquired from Lord Airlie the lands and Barony of Forter (22),

in Glenisla, which comprised roughly the whole of that part of Angus

west of the Isla from Mount Blair right up to the Aberdeenshire border;

a far richer property than his ancient patrimony in Glenshee, which he

proceeded to sell to his second-cousin Donald Farquharson the following

year (23). Thus, after having been seated in Glenshee for probably

rather more than a century and-a-half, the MacThomas chiefs, now at the

height of their prosperity, passed over to Glenisla and the stage is set

for their final, sudden and complete ruin.

R. F. P.

1) Viz., p. 3.

2) Colin Gibson Bonnie Glenshee, p. 70.

3) A. M. Mackintosh Mackintosh Families in Glenshee and Glenisla, 1916

p. 44.

4) W. M Combie Smith Memoir of the Families of M'Combie and Thoms, 1889.

pp. 6, 16 & 198, n. D.; also A. M. Mackintosh op. cit. pp. 4I &

43- 4. Sheilings were high moorland pastures where the cattle were

grazed in summer; Gormel being about 3 miles up Glenbeg which forms a

natural consummation of Glenshee joining it roughly at the Spittal.

5) W. M Combie Smith op. cit., p. 17- 8 & 199 n. F.; also A. M.

Mackintosh op. cit., p. 41.

6) A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit., p. 44. The word town. in this context

merely means a group of farm buildings.

7) The Glen Garry mentioned here lies in Atholl, just west of Blair

Atholl and is not the glen of the same name in the Western Highlands;

home of the MacDonells of Glengarry;

8) Colin Gibson, op. cit., pp. 2l &34.

9) The division between the MacThomas and Rattray shielings in Glenbeg

was the subject of an agreement on 15th June l567. A. M. Mackintosh op.

cit., p 44.

10) Colin Gibson, op. cit., p 34.

11) Latta MS. (viz., The Scottish Genealogist, Vol. XII N. 4, p. 91, n5)

12. A. M. Mackintosh, op, cit., p. 45. His grandfather (named in the

Instrument <.Makcomas,>) had already been granted an Instrument of

tolerance on 11th November 1577, allowing him to pasture his beasts

there. ibid. p. 44 See also W. M. Combie Smith, op. cit. PP. 18-'9 &

199- n C:

13) Viz.,. p. 10.

14). A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit., p. 47.

15) ibid., p. 47; also W. M'Combie Smith, op. cit., p. 19.

16) The adherents of the National Covenant (to upho1d Presbyterianism).

The power of the Presbyterian Church at the time is well illustrated in

the Kirkmichael kirk session records, which shew that Iain Mor of

Finegand was himself humbled by the Kirk, on 2nd March 1651, when he and

two of his tenants made public satisfaction in sackcloth, and gave

evidences of their repentance for deceiving the minister be causing hin1

baptize ane child gottin in fornication, under the notione of a lawll.

chyld. .M'Combie Smith, Op. cit., p. 199, n. E.

17) W. M'Combie Smith, Op.Cit.p.165, mentions a tradition that Montrose

and Iain Mor became personal friends, and infers from the formers letter

to the Tutor of Strowan, dated from Glenshee on 10th June 1646 (9 months

after Philiphaugh), that

was then a guest at Finegand.

18) A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit., p. 52.

19) ibid., p. 53; also W. M'Combie Smith, op. Cit., p. 203-'5, n. N.

20) He appears in the Roll of those to whom the Major-Genll. has given

Remissions and Assurances upon their enacting themselves betwixt and the

1st November 1646. (A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit. p. 53).

21) ibid., p. 47.; also W. M Combie Smith, op. cit., p. 20.

22) A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit. pp. 48-51; also W. M Combie Smith op.

cit., PP- 30'- 6.

23) A. M. Mackintosh, op. cit., p. 48; also W. M Combie Smith, op. cit.,

pp. 28-31 & 200, n. I.

My thanks to Cathy, the

Convenor of the US & Canadian Branch of Clan MacThomas Society for

sending me in these pictures...

Chief Andrew MacThomas (on the rock) and

Vice President Robin Thomas at the Cockstane. |