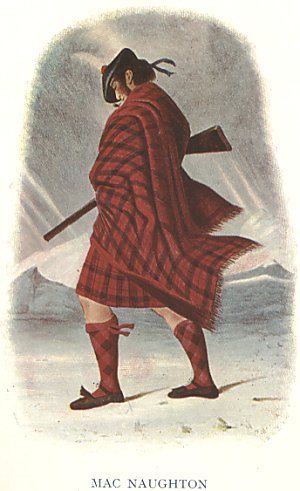

|

The clan Nachtan or Macnaughton is supposed by

Mr Skene to have originally belonged to Moray.

The MS of 1450 deduces the descent of the heads of the clan from Nachtan Mor, who is

supposed to have lived in the 10th century. The Gaelic name Neachtain is the same as the

Pictish Nectan, celebrated in the Pictish Chronicle as one of the great Celitc divisions

in Scotland, and the appellation is among the most ancient in the north of Ireland, the

original seat of the Cruithen Picts. According to Buchanan of Auchmar, the heads of this

clan were for ages thanes of Loch Tay, and possessed all the country between the south

side of Loch-Fyne and Lochawe, parts of which were Clenira, Glenshira, Glenfine, and other

places, while their principal seat was Dunderraw on Loch-Fyne.

In the reign of Robert III, Maurince or Morice Macnaughton had a charter from Colin

Campbell of Lochow of sundry lands in Over Lochow, but their first settlement in

Argyleshire, in the central parts of which their lands latterly wholly lay, took place

long before this. When Malcolm the Maiden attempted to civilise the ancient province of

Moray, by introducing Norman and Saxon families, such as the Bissets, the Comyns, &c.,

in the place of the rude Celtic natives whom he had expatriated to the south, he gave

lands in or near Strathtay or Strathspey, to Nachtan of Moray, for those he had held in

that province. He had there a residence called Dunnachtan castle. Nesbit describes this

Nachtan as "an eminent man in the time of Malcolm IV", and says that he

"was in great esteem with the family of Lochawe, to whom he was very assistant in

their wars with the Macdougals, for which he was rewarded with sundry lands". The

family of Lochawe here mentioned were the Campbells.

The Macnaughtons appear to have been fairly and finally settled in Argyleshire previous to

the reign of Alexander III, and Gilchrist Macnaughton, styled of that ilk, was by that

monarch appointed in 1287, heritable keeper of his castle and island of Frechelan (Fraoch

Ellan) on Lochawe, on condition that he should be properly entertained when he should pass

that way; whence a castle embattled was assumed as the crest of the family.

This GIlchirst was father or grandfather of Donald Macnaughton of that ilk, who, being

nearly connected with the Macdougals of Lorn, joined that powerful chief with his clan

against Robert the Bruce, and fought against the latter at the battle of Dalree in 1306,

in consequence of which he lost a great part of his estates. In Abercromby's Martial

Achievements, it is related that the extraordinary courage shown by the king in having, in

a narrow pass, slain with his own hand several of his pursuers, and amongst the rest three

brothers, so greatly excited the admiration of the chief of the Macnaughtons that he

became thenceforth on of his firmest adherents.

His son and successor, Duncan Macnaughton of that ilk, was a steady and loyal subject to

King David II, who, as a reward for his fidelity, conferred on his his son, Alexander,

lands in the island of Lewis, a portion of the forfeited possessions of John of the Isles,

which the chiefs of the clan Naughton held for a time. The ruins of their castle of

Macnaughton are still pointed out on that island.

Donald Macnaughton, a younger son of the family, was, in 1436, elected bishop of Dunkeld,

in the reign of James I.

Alexander Macnaughton of that ilk, who lived in the beginning of the 16th century, was

knighted by James IV, whom he accompanied to the disastrous field of Flodden, where he was

slain, with nearly the whole chivalry of Scotland. His son, John, was succeeded by his

second son, Malcolm Macnaughton of Glenshira, his eldest son having predeceased him.

Malcolm died in the end of the reign of James VI, and was succeeded by his eldest son,

Alexander.

John, the second son of Malcolm, being of a handsome appearance, attracted the notice of

King James VI, who appointed him one of his pages of honour, on his accession to the

English crown. He became rich, and purchased lands in Kintyre. His elder brother,

Alexander Macnaughton of that ilk, adheared firmly to the cause of Charles I, and in his

service sustained many severe losses. At the Restoration, as some sort of compensation, he

was knighted by Charles II, and, unlike many others, received from that monarch a liberal

pension for life. Sir Alexander Macnaughton spent his later days in London, where he died.

His son and successor, John Macnaughton of that ilk, succeeded to an estate greatly

burdened with debt, but did not hesitate in his adherence to the fallen fortunes of the

Stuarts. At the head of a considerable body of his own clan, he joined Viscount Dundee,

and was with him at Killiecrankie. James VII signed a deed in his favour, restoring to his

family all its old lands and hereditary rights, but, as it never passed the seals in

Scotland, it was of no value. His lands were taken from him, not by forfeiture, but

"the estate", says Buchanan of Auchmar, "was evicted by creditors for sums

noways equivalent to its value, and, there being no diligence used for relief therefore,

it went out of the hands of the family". His son, Alexander, a captain in Queen

Anne's guards, was killed in the expedition to Vigo in 1702. His brother, John, at the

beginning of the last century was for many years collector of customs at Anstruther in

Fife, and subsequently was appointed inspector-general in the same department. The direct

male line of the Macnaughton chiefs became extinct at his death.

"The Mackenricks are ascribed to the Macnaughton line, as also families of Macnights

(or Macneits), Macnayers, Macbraynes, and Maceols". The present head of the

Macbraynes is John Burns Macbrayne, grandson of Donald Macbrayne, merchant in Glasgow, who

was great-grandson, on the female side, of Alexander Macnaughton of that ilk, and heir of

line of John Macnaughton, inspector-general of customs in Scotland. On this account the

present representative of the Macbraynes is entitled to quarter his arms with those of

Macnaughtons.

There are still Athole families of the Macnaughton name, proving so far what has been

stated respecting their early possession of lands in that district. Stewart of Garth makes

most honourable mention of one of the sept, who was in the service of Menzies of Culdares

in the year 1745. That gentleman had been "out" in 1715, and was pardoned.

Grateful so far, he did not join Prince Charles, but sent a fine charger to him as he

entered England. The servant, Macnaughton, who conveyed the present, was taken and tried

at Carlisle. The errand on which he had come was clearly proved, and he ws offered pardon

and life if he would reveal the name of the sender of the horse. He asked with indignation

if they supposed that he could be such a villain. They repeated the offer to him on the

scaffold, but he died firm to his notion of fidelity. His life was nothing to that of his

master, he said. The brother of this Macnaughton was known to Garth, and was one of the

Gael who always carried a weapon about him to his dying day.

Another Account of the Clan

BADGE: Lusan Albanach

(azalea procumbeus) trailing azalea.

SLOGAN: Fraoch Eilean.

THROUGHOUT

the legend-haunted

Highlands, where every island, glen, and hillside has its strange and

tender story of the past, no district is more crowded with old romance

than that of Loch Awe. Here lay the heart of the old Oire Gaidheal, or

Argyll—the Land of the Gael—headquarters of the Scots after their

early settlement in this country in the days of St. Columba. Even at that

time the islands and shores of Loch Awe seem to have been a region of old

wonder and story, and from then till now traditions have gathered about

these lovely shores, till the unforgotten deeds of clansmen long since

dust would make a book of which one should never tire of turning the

pages. THROUGHOUT

the legend-haunted

Highlands, where every island, glen, and hillside has its strange and

tender story of the past, no district is more crowded with old romance

than that of Loch Awe. Here lay the heart of the old Oire Gaidheal, or

Argyll—the Land of the Gael—headquarters of the Scots after their

early settlement in this country in the days of St. Columba. Even at that

time the islands and shores of Loch Awe seem to have been a region of old

wonder and story, and from then till now traditions have gathered about

these lovely shores, till the unforgotten deeds of clansmen long since

dust would make a book of which one should never tire of turning the

pages.

The origin of the loch itself is the subject of a

legend which must have been told to wondering ears a thousand times in the

most dim and misty past. According to that legend the bed of the loch was

once a fair and fertile valley, with sheilings and cattle and cornfields,

where the reapers sang at harvest time. It had always upon it, however,

the fear of the day of fate. High on the side of Ben Cruachan, that

mightier Eildon of the Highlands, with its strange triple summit, was a

fairy spring which must always be kept covered. For generations this was

jealously done, but as time went on and no trouble came, the folk grew

less careful. At last one day a girl who went to draw water forgot to

replace the cover on the spring. All night the water flowed and swelled in

a silver flood, and when morning broke, in place of the fertile valley, a

far-reaching loch, studded with islands like green and purple jewels,

stretched away through the winding valleys of the hills.

Each of the islands, again, has its own tradition more

or less strange or romantic. Of these tales one of the earliest is that of

Inis Fraoch. In English to-day the name is taken to mean the Heather Isle,

but another origin is given to it in one of the early songs of Ossian, to

be found in old Gaelic manuscript and tradition. According to this legend

there grew on the island a tree, the apples of which possessed the virtue

of conferring immortal youth. This tree and its fruit were jealously

guarded by a fierce dragon. The hero, Fraoch, loved and was loved by the

fair Gealchean, and all would have gone well had not the girl’s mother,

Mai, also become enamoured of the youth. Mai herself had once been a

lovely woman, but the years had robbed her of her charms, and, moved by

her passion, she became consumed with a desire to have these restored. She

had heard of the apples of immortal youth which grew on Inis Fraoch, but

the fear of the dragon which guarded them prevented her trying their

efficacy. Driven at last to desperation, she induced Fraoch himself to go

to the island and bring her the fruit. Fraoch set out, while Mal gave

herself up to dreams of the effect which her restored charms would have

upon him. As he secured the apples he was attacked by the dragon, and a

terrible combat took place. In the end the beast was slain, but in the

encounter Fraoch also received a wound, and the eager Mai had only

received the fruit from his hand when she had the mortification to see him

expire at her feet.

At a later day Inis Fraoch

became the stronghold of the MacNaughton chiefs. According to the Gaelic

manuscript of 1450, so much relied upon by Skene in his Highlanders, of

Scotland, the clan was already, in the days of David I., a powerful

tribe in the north, in the district of Moray. The name is said to be

identical with the Pictish Nectan, and a shadowy trace of its importance

in an earlier time is to be found in the names of Dunecht and Nectansmere

in Fife, the latter famous for the great victory of the Picts in the year

685 over the invading forces of Ecgfrith the Northumbrian king, from which

only a solitary fugitive escaped. Thirty-two years later, Nectan, son of

Deriloi, was, according to Bede and Tighernac, the Pictish king who built

Abernethy with its round tower on the lower Earn, and made it the capital

of the Pictish Church. According to tradition, however, the clan took its

name from Nachtan, a hero of the time of Malcolm IV., in the middle of the

twelfth century.

In keeping with the

tradition of their Pictish origin, the chiefs are said to have been for

ages Thanes of Loch Tay. Afterwards they are said to have possessed all

the country between Loch Fyne and Loch Awe, and in 1267 King Alexnnder

III. appointed Gilchrist MacNaughton hereditary keeper of the island and

castle of Inis Fraoch on condition that when the king passed that way he

should be suitably entertained by the MacNaughton chief. At the time of

the wars of Bruce, Donald, chief of the MacNaughtons, being closely

related to the great MacDougal Lords of Lorne, at first took their side

against the king. At the battle in the pass of Dalrigh, however, as

described in Barbour’s Bruce, MacNaughton, who was with the Lord

of Lorne, was a witness of the king’s prowess in ridding himself of the

three brothers who attacked him all at once as he defended the rear of his

little army retreating through a narrow pass. The MacNaughton chief

expressed his admiration of Bruce’s achievement, and was sharply taken

to task by the Lord of Lorne:

"It seems it likes

thee, perfay,

That he slays yon gate our mengye!"

From that time MacNaughton took the side of

the king, and in the days of David II., Bruce’s son, the next chief,

Duncan, was a strong supporter of the Scottish Royal house. As a reward

for the support of the clan, David II. conferred on the next chief,

Alastair MacNaughton, all the forfeited lands of John Dornagil, or White

Fist, and of John, son of Duncan MacAlastair of the Isles. The MacNaughton

chief thus became a great island lord as well as the owner of broad lands

in old Argyll.

Another Alastair

MacNaughton, who was chief in the time of James IV., was knighted by that

king, and led his clan to battle in that great rush of the men of the

Highlands and Isles which carried all before it at the beginning of the

battle of Flodden. There, however, he himself fell. He was succeeded by

two of his sons in turn, John and Malcolm of Glenshira. This Malcolm’s

second son, another John, was noted for his handsome person. His good

looks attracted the attention of James VI., who, while not particularly

prepossessing himself, appears to have had a keen appreciation of a good

presence in other men, and to have had a penchant for retaining them about

his court. In this way the king "who never said a foolish thing and

never did a wise one" kept near his person such men as the Bonnie

Earl of Moray, Francis, Earl of Bothwell, Esme Stewart, Duke of Lennox,

and George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. For the same reason, on

succeeding to the English throne, he made Glenshira’s son one of his

pages of honour. In this position John MacNaughton became a man of means,

and, returning to his native district, purchased a good estate in Kintyre.

The chiefs of MacNaughton

were now at the summit of their fortunes. Alexander, Malcolm’s eldest

son and successor, was a well-known figure at the court of Charles I. In

1627, during the war with France, that king gave him a Commission, "

With ane sufficient warrant to levie and transport twa hundrethe

bowmen," to take part against the country’s enemies. This warrant

is curious evidence of the use of an ancient weapon at that late period in

the Highlands. The Laird of MacKinnon contributed part of the force, and

the two hundred were soon got together and set sail. On the passage,

however, they came near to disaster, their transport being twice driven

into Falmouth and " Hetlie followit by ane man of warr" of

France. The Highlanders happened to be accompanied by their pipers and a

harper, and, according to Donald Gregory in the Archceologia Scotica,

the Frenchman were prevented from attacking by the awe-inspiring sound and

sight of the "Bagg-pypperis and marlit plaidis." In the civil

wars of Charles I. MacNaughton remained a staunch Royalist, and at the

court of Charles II., after the Restoration, as Colonel Macnachtan, he was

a great favourite of that king. When he died at last in London, Charles

buried him at his own expense in the chapel royal.

John, the next chief, was

no less staunch a Royalist. At the Revolution, with a strong force of his

clan, he joined James VII.’s general, Viscount Dundee, and is said to

have taken a leading part in the overthrow of King William’s troops at

Killiecrankie in 1689. After the battle, and the death of Dundee, he, with

his son Alexander and the other leaders of the little Jacobite army,

signed the letter of defiance sent to the commander of King William’s

forces, General MacKay; and he also entered into a bond with other

Jacobite chiefs, by which he undertook to appear with fifty men for the

cause of King James, at whatever place and time might be appointed. The

result of his Jacobite activities was disaster to his house. In 1691 an

Act of Forfeiture was passed by the Scottish Parliament which deprived him

of his estates.

The wife of this chief was

a sister of that crafty schemer, Sir John Campbell, fifth baronet of

Glenurchie, who became, first, Earl of Caithness and afterwards Earl of

Breadalbane and Holland; and his son Alexander, already referred to,

became a captain in Queen Anne’s Lifeguards. He might have restored the

family fortunes, but was killed in the expedition to Vigo in 1702. The

chiefship then passed to his brother John, but the latter also died

without heirs of his body, and the chiefship became extinct.

Both Charles II. and James

VII. had intended to confer substantial honours on the MacNaughton chiefs,

the former with a charter of the hereditary sheriffship of Argyll, and the

latter with a commission as steward and hereditary bailie of all the lands

which he and his ancestors had ever possessed; but in the former case the

patent, by reason of some court intrigue, never passed the seals, and in

the second case, though the deed was signed by the king and counter-signed

by the Earl of Perth, its purpose was defeated by the outbreak of the

Revolution.

In 1747, in the report made

by Lord President Forbes on the strength of the Highland chiefs, the

MacNaughtons appear as a broken clan, being classed with several others

who inhabited the district. Like the MacArthurs, MacAlisters, MacGregors,

MacNabs, and Fletchers, who had formerly flourished on the shores of Loch

Awe, they had no longer a chief to lead them and further their interests,

and the broad MacNaughton lands had passed for the most part into the

hands of their shrewd neighbours, the Campbells. Memorials only of their

ancient greatness are to be seen in the ruined stronghold of Inis Fraoch

in Loch Awe, of Dunderaw, now restored, on the shore of Loch Fyne, of

MacNachtan Castle in the Lews, and others—in particular, belonging to a

still earlier day, that of Dunnachton in Strathspey.

Septs of Clan MacNaughton:

Kendrick, Hendry, Maceol, MacBrayne, MacHendry, MacKendrick, MacKenrick,

Macknight, MacNair, MacNayer, MacNiven, MacNuir, MacNuyer, MacVicar, Niven,

Weir.

|