|

| |

|

According to the Mackintosh MS histories the

first of which was compiled about 1500, the progenitor of the family was Shaw or Seach, a

son of Macduff, Earl of Fife, who, for his assistance in quelling a rebellion among the

inhabitants of Moray, was presented by King Malcolm IV with the lands of Petty and

Breachly and the forestry of Strathearn, being made also constable of the castle of

Inverness. From the high position and power of his father, he was styled by the

Gaelic-speaking population Mac-an-Toisich, i.e. "son of the principle or

foremost". Tus, tos, or tosich, is "beginning or first part of anything",

whence "foremost" or "principal". Mr Skene says the tosich was the

oldest cadet of a clan, and that Mackintosh's ancestor was oldest cadet of clan Chattan.

Professor Cosmo Innes says the tosich was the administrator of the crown lands, the head

man of a little district, who became under the Saxon title of Thane hereditary tenant; and

it is worthy of note that these functions were performed by the successor of the above

mentioned Shaw, who, the family history says, "was made chamberlain of the king's

revenues in those parts for life". It is scarcely likely, however, that the name

Mackintosh arose either in this manner or in the manner stated by Mr Skene, as there would

be many tosachs, and in every clan an oldest cadet. The name seems to imply some

peculiar

circumstances, and these are found in the son of the great Thane of Earl of Fife.

Little is known of the immediate successors of Shaw Macduff. They appear to have made

their residence in the castle of Inverness, which they defended on several occasions

against the marauding bands from the west. Some of them added considerably to the

possessions of the family, which soon took firm root in the north. Towards the close of

the 13th century, during the minority of Angus MacFerguhard, 6th chief, the Comyns seized

the castle of Inverness, and the lands of Geddes and Rait belonging to the Mackintoshes,

and these were not recovered for more than a century. It was this chief who in 1291-2

married Eva, the heiress of clan Chattan, and who acquired with her the lands occupied by

that clan, together with the station of leader of her father's clansmen. He appears to

have been a chief of great activity, and a staunch supporter of Robert Bruce, with whom he

took part in the battle of Bannockburn. He is placed second in the list of chiefs given by

General Stewart of Garth as present in this battle. In the time of his son William the

sanguinary feud with the Camerons broke out, which continued up to the middle of the 17th

century. The dispute arose concerning the lands of Glenlui and Locharkaig, which Angus

Mackintosh had acquired with Eva, and which in his absence had been occupied by the

Camerons. William fought several battles for the recovery of these lands, to which in 1337

he acquired a charter from the Lord of the Isles, confirmed in 1357 by David II, but his

efforts were unavaling to dislodge the Camerons. The feud was continued by his successor,

Lauchlan, 8th chief, each side occasionally making raids into the other's country. In one

of these is said to have occurred the well-known dispute as to precedency between two of

the septs of clan Chattan, the Macphersons and the Davidsons. According to tradition, the

Camerons had entered Badenoch, where Mackintosh was then residing, and had seized a large

"spreagh". Mackintosh's force, which followed them, was composed chiefly of

these two septs, the Macphersons, however, considerably exceeding the rest. A dispute

arising between the two respective leaders of the Macphersons and Davidsons as to who

should lead the right wing, the chief of the Mackintosh, as superior to both, was appealed

to, and decided in favour of Davidson. Offended at this, the Macphersons, who, if all

accounts are true, had undoubtedly the better right to the post of honour, withdrew from

the field of battle, thus enabling the Camerons to secure a victory. When, however, they

saw that their friends were defeated, the Macphersons are said to have returned to the

field, and turned the victory of the Camerons into a defeat, killing their leader, Charles

MacGillonie. The date of this affair, which took place at Inverahavon, is variously fixed

at 1370 and 1384, and some writers make it the cause which led to the famous battle on the

North Inch of Perth twenty-six years later.

As is well known, great controversies have raged as to the clans who took part in the

Perth fight, and those writers just referred to decide the question by making the

Macphersons and Davidsons the combatant clans.

Wyntoun's words are:

"They three score were clannys twa,

Clahynnhe Qwhewyl and Clachinyha,

Of thir twa kynnys war thay men,

Thretty again thretty then,

And thare thay had thair chiftanys twa,

scha Farqwharis Sone wes ane of thay,

The tother Chrsity Johnesone".

On this the Rev W G Shaw of Forfar remarks, - "One writer (Dr Macpherson) tried to

make out that the clan Yha or Ha was the clan Shaw. Another makes them to be the clan Dhai

or Davidsons. Another (with Skene) makes them Macphersons. As to the clan Quhele, Colonel

Robertson (author of 'Hisorical Proofs of the Highlanders') supposes that the clan Quhele

was the clan Shaw, partly from the fact that in the Scots Act of Parliament of 1392 (vol

i.p.217), whereby several clans were forfeited for their share in the raid of Angus, there

is mention made of Slurach, or (as it is supposed it ought to have been written) Sheach et

omnes clan Quhele. The others again suppose that the clan Quhele was the clan Mackintosh.

Others that it was the clan Cameron, whilst the clan Yha was the Clan-na-Chait or clan

Chattan.

"From the fact that, after the clan Battle on the Inch, the star of the Mackintoshes

was decidedly in the ascendant, there can be little doubt but that they formed at least a

section of the winning side, whether that side were the clan Yha or the clan Quhele.

"Wyntoun declines to say on which side the victory lay. He writes - 'Wha had the waur

fare at the last, I will nocht say'. It is not very likely that subsequent writers knew

more of the subject than he did, so that after all, we are left very much to the tradition

of the families themselves for information. The Camerons, Davidsons, Mackintoshes and

Macphersons, all say that they took part in the fray. The Shaws' tradition is, that their

ancestor, being a relative of the Mackintoshes, took the place of the aged chief of that

section of the clan, on the day of battle. The chroniclers vary as to the names of the

clans, but they all agree as to the name of one of the leaders, viz, that it was Shaw.

Tradition and history are agreed on this one point.

"One thing emerges clearly from the confusion as to the clans who fought, and as to

which of the modern names of the contending clans was represented by the clans Yha and

Quhele, - one thing emerges, a Shaw leading the victorious party, and a race of Shaws

sprining from him as their great - if not their first - founder, a race, who for ages

afterwards, lived in the district and fought under the banner of the Laird of Mackintosh.

As to the Davidsons, the tradition which vouches for the particulars of the fight at

Invernahavon expressly says that the Davidsons were almost to a man cut off, and it is

scarcely likely that they would, within so short a time, be able to muster sufficient men

either seriously to disturb the peace of the country or to provide thirty champions. Mr

Skene solves the question by making the Mackintoshes and Macphersons the combatant clans,

and the cause of quarrel the right to the headship of clan Chattan. But the traditons of

both families place them on the winning side, and there is no trace whatever of any

dispute at this time, or previous to the 16th century, as to the chiefship. The mopst

probable solution of this difficulty is, that the clans who fought at Perth were the clan

Chattan (i.e., Mackintoshes, Macphersons, and others) and the Camerons. Mr Skene, indeed,

says that the only clans who have a traditon of their ancestors having been engaged are

those clans, though he endeavours to account for the presence of the last names clan by

making them assist the Macphersons against the Mackintoshes. The editor of the Memoirs of

Lochiel, mentioning this tradition of the Camerons, as well as the opinion of Skene, says.

- "It may be observed, that the side alloted to the Camerons (viz the unsuccessful

side) afford the strongest internal evidence of its correctness. Had the Camerons been

described as victors it would have been very different".

The author of the recently discoverd MS account of the clan Chattan already referred to,

says that by this conflict Cluny's right to lead the van was established; and in the

meetings of clan Chattan he sat on Mackintosh's right hand, and when absent that seat was

kept empty for him. Henry Wynde likewise associated with the clan Chattan, and his

descendants assumed the name of Smith, and were commonly called Sliochd a Gow Chroim.

Lauchlan, chief of Mackintosh, in whose time these events happened, died in 1407, at a

good old age. In consequence of his age and infirmity, his kinsman, Shaw Mackintosh, had

headed the thirty clan Chattan champions at Perth, and for his success was rewarded with

the possessions of the lands of Rothiemurchus in Badenoch. The next chief, Ferquhard, was

compelled by his clansmen to resign his post in consequence of his mild, inactive

disposition, and his uncle Malcolm (son of William Mac-Angus by a second marriage)

succeeded as 10th chief of Mackintosh, and 5th captain of clan Chattan. Malcolm was one of

the most warlike and successful of the Mackintosh chiefs. During his long chiefship of

nearly fifty years, he made frequent incursions into the Cameron territories, and waged a

sanguinary war with the Comyns, in which he recovered the lands taken from his ancestor.

In 1411 he was one of the principle commanders in the army of Donald, Lord of the Isles,

in the battle of Harlaw, where he is by some stated incorrectly to have been killed. In

1429, when Alexander, Lord of the Isles and Earl of Ross, broke out into rebellion at the

head of 10,000 men, on the advance of the king into Lochaber, the clan Chattan and the

clan Cameron deserted the earl's banners, went over to the royal army, and fought on the

royal side, the rebels being defeated. In 1431, Malcolm Mackintosh, captain of the clan

Chattan, received a grant of the lands of Alexander of Lochaber, uncle of the Earl of

Ross, that chieftain having been forfeited for engaging in the rebellion of Donald

Balloch. Having afterwards contrived to make his peace with the Lord of the Isles, he

received from him, between 1443 and 1447, a confirmation of his lands in Lochaber, with a

grant of the office of bailiary of that district. His son, Duncan, styled captain of the

clan Chattan in 1467, was in great favour with John, Lord of the Isles and Earl of Ross,

whose sister, Flora, he married, and who bestowed on him the office of steward of

Lochaber, which had been held by his father. He also received the lands of Keppoch and

others included in that lordship.

On the forfeiture of his brother-in-law in 1475, James III granted to the same Duncan

Mackintosh a charter, of date July 4th, 1476, of the lands of Moymore, and various others,

in Lochaber. When the king in 1493 proceeded in person to the West Highlands, Duncan

Mackintosh, captain of the clan Chattan, was one of the chiefs, formerly among the vassals

of the Lord of the Isles, who went to meet him and make their submission to him. These

chiefs received in return royal charters of the lands they had previously held under the

Lord of the Isles, and Mackintosh obtained a charter of the lands of Keppoch, Innerorgan,

and others, with the office of bailiary of the same. In 1495, Garquhar Mackintosh, his

son, and Kenneth Oig Mackenzie of Kintail, were imprisoned by the king in Edinburgh

castle. Two years thereafter, Farquhar, who seems about this time to have succeeded his

father as captain of the clan Chattan, and Mackenzie, made their escape from Edinburgh

castle, but, on their way to the Highlands, they were seized at Torwood by the laird of

Buchanan. Mackenzie, having offered resistance, was slain, but Mackintosh was taken alive,

and confined at Dunbar, where he remained till after the battle of Flodden.

Farquhar was succeeded by his cousin, William Mackintosh, who had married Isabel M'Niven,

heiress of Dunnachtan; but John Roy Mackintosh, the head of another branch of the family,

attempted by force to get himself recognised as captain of the clan Chattan, and failign

in his design, he assassinated his rival at Inverness in 1515. Being closely pursued,

however, he was overtaken and slain at Glenesk. Lauchlan Mackintosh, the brother of the

murdered chief, was then placed at the head of the clan. He is described by Bishop Lesley

as "a verrie honest and wyse gentleman, an barroun of gude rent, quha keipit hes hole

ken, friendes and tennentis in honest and guid rewll". The strictness with which he

ruled his clan raised him up many enemies among them, and, like his brother, he was cut

off by the hand of an assassin. "Some wicked persons", says Lesley, "being

impatient of virtuous livng, stirred up one of his own principal kinsmen, called James

Malcolmson, who cruelly and treacherously slew his chief". This was in the year 1526.

To avoid the vengeance of that portion of the clan by whom the chief was beloved,

Malcolmson and his followers took refuge in the island in the loch of Rothiemurchus, but

they were pursued to their hiding place, and slain there.

Lauchlan had married the sister of the Earl of Moray, and by her had a son, William, who

on his father's death was but a child. The clan therefore made a choice of Hector

Mackintosh, a bastard son of Farquhar, the chief who had been imprisoned in 1495, to act

as captain till the young chief should come of age. On attaining the age of manhood

William duly became head of the clan, and having been well brought up by the Earls of

Moray and Cassilis, both his near relatives, was, according to Lesley, "honoured as a

perfect pattern of virtue by all the leading men of the Highlands". During the life

of his uncle, the Earl of Moray, his affairs prospered; but shortly after that noble's

death, he became involved in a feud with the Earl of HUntly. He was charged with the

heinous offence of conspiring against Huntly, the queen's lieutenant, and at a court held

by Huntly at Aberdeen, on the 2d August 1550, was tried and convicted by a jury, and

sentanced to lose his life and lands. Being immediately carried to Strathbogie, he was

beheaded soon after by Huntly's countess, the earl himself having given a pledge that his

life should be spared. The story is told, though with grave errors, by Sir Walter Scott,

in his Tales of a Grandfather. By Act of Parliament on 14th December 1557, the sentance

was reversed as illegal, and the son of Mackintosh was restored to all his father's lands,

to which Huntly added others as assythment for the blood. But this act of atonement on

Huntly's part was not sufficient to efface the deep grudge owed him by the clan Chattan on

account of the execution of their chief, and he was accordingly thwarted by them in many

of his designs.

In the time of this earl's grandson, the clan Chattan again came into collision with the

powerful Gordons, and for four years a deadly feud ranged between them. In consequence of

certain of Huntly's proceedings, especially the murder of the Earl of Moray, a strong

faction was formed against him, Luchlan, 16th chief of Mackintosh, taking a prominent

part.

In this feud Huntly succeeded in detaching the Macphersons belonging to the Cluny branch

from the rest of clan Chattan, but the majority of that sept, according to the MS history

of the Mackintoshes, remained true to the chief of Mackintosh. These allies, however, were

deserted by Huntly when he became reconclied to Mackintosh, and in 1609 Andrew Macpherson

of Cluny, with all the other principal men of clan Chattan, signed a bond of union, in

which they all acknowledged the chief of Mackintosh as captain and chief of clan Chattan.

The clan Chattan were in Argyll's army at the battle of Glenlivat in 1595, and with the

Macleans formed the right wing, which made the best resistance to ther Catholic earls, and

was the last to quit the field.

Cameron of Lochiel had been forfeited in 1598 for not producing his title deeds, when

Mackintosh claimed the lands of Glenluy and Locharkaig, of which he had kept forcible

possession. In 1618 Sir Lauchlan, 17th chief of Mackintosh, prepared to carry into effect

the acts of outlawry against Lochiel, who, on his part, put himself under the protection

of the Marquis of Huntly, Mackintosh's motal foe. In July of the same year Sir Lauchlan

obtained a commission of fire and sword against the Macdonalds of Keppoch for laying waste

his lands in Lochaber. As he conceived that he had a right to the services of all his

clan, some of whom were tenants and dependents of the Marquis of Huntly, he ordered the

latter to follow him, and compelled such of them as were refractory to accompany him into

Lochaber. This proceeding gave great offence to Lord Gordon, Earl of Enzie, the marquis's

son, who summoned Mackintosh before the Privy Council, for having, as he asserted,

exceeded his commission. He was successful in obtaining the recall of Sir Lauchlan's

commission, and obtaining a new one in his own favour.

During the wars of the Covenant, William 18th chief, was at the head of he clan, but owing

to feebleness of constitution took no active part in the troubles of that period. He was

however a decided loyalist, and among the Mackintosh papers are several letters, both from

the unhappy Charles II, acknowledging his good affection and service. The Mackintoshes, as

well as the Macphersons and Farquharsons, were with Montrose in considerable numbers, and,

in fact, the great body of clan Chattan took part in nearly all that noble's battles and

expeditions.

Shortly after the accession of Charles II, Lauchlan Mackintosh, to enforce his claims to

the disputed lands of Glenluy and Locharkaig against the Camerons of Lochiel, raised his

clan, and, assisted by the Macphersons, marched to Lochaber with 1500 men. He was me by

Lochiel with 1200 men, of whom 300 were Macgregors. About 300 were armed with bows.

General Stewart says - "When preparing to engage, the Earl of Breadalbane, who was

nearly related to both chiefs, came in sight with 500 men, and sent them notice that if

either of them refused to agree to the terms which he had to propose, he would throw his

interest unto the opposite scale. after some hesitation his offer of mediation was

accepted, and the feud amicably and finally settled". This was in 1665 when the

celebrated Sir Ewan Cameron was chief and a satisfactory arrangement having been made, the

Camerons were at length left in undisputed possession of the lands of Glenluy and

Locharkaig, which their various branches still enjoy.

In 1672 Duncan Macpherson of Cluny, having resolved to throw off all connecxion with

Mackintosh, made application to the Lyon office to have his arms matriculated as laird of

Cluny Macpherson, and "the only and true representative of the ancient and honourable

family of the clan Chattan". This request was granted; and, soon afterwards, when the

Privy Council required the Highland chiefs to give security for the peaceable behaviour of

their respective clans, Macpherson became bound for his clan under the designation of the

lord of Cluny and chief of the Macphersons; as he could only hold himself responsible for

that portion of the clan Chattan which bore his own name and were more partuculary under

his own control. As soon as Mackintosh was informed of this circumstance, he applied to

the privy council and the Lyon office to have his own title declared, and that which had

been granted to Macpherson recalled and cancelled. An inquiry was accordingly instituted,

and both parties were ordered to produce evidence of their respective assertions, when the

council ordered Mackintosh to give bond for those of his clan, his vassals, those

descended of his family, his men, tenants, and servants, and all dwelling upon his ground;

and enjoined Cluny to give bond for those of his name of Macpherson, descended of his

family, and his men, tenants, and servants, "without prejudice always to the laird of

Mackintosh". In consequence of this decision, the armorial bearings granted to

Macpherson were recalled, and they were again matriculated as those of Macpherson of

Cluny.

Between the Mackintoshes and the Macdonalds of Keppoch, a feud had long existed,

originating in the claim of the former to the lands occupied by the latter, on the Braes

of Lochaber. The Macdonalds had no other right to their lands than what was founded on

prescriptive possession, whilst the Mackintoshes had a feudal title to the property,

originally granted by the Lords of the Isles, and, on their forfeiture, confirmed by the

crown. After various acts of hostility on both sides, the feud was at length terminated by

"the last considerable clan battle which was fought in the Highlands". To

disposses the Macdonalds by force, Mackintosh raised his clan, and, assisted by an

independent company of soldiers, furnished by the government, marched towards Keppoch,

but, on his arrival there, he found the place deserted. He was engaged in constructing a

fort in Glenroy, to protect his rear, when he received by their kinsmen of Glengarry and

Glencoe, were posted in great force at Mulroy. He immediately marched against them, but

was defeated and taken prisoner. At that critical moment, a large body of Macphersons

appeared on the ground, hastening to the relief of the Mackintoshes, and Keppoch, to avoid

another battle, was obliged to release his prisoner. It is highly to the honour of the

Macphersons, that they came forward on the occasion so readily, to the assistance of the

rival branch of the clan Chattan, and that so far from taking advantage of Mackintosh's

misfortune, they escorted him safely to his own territories, and left him without exacting

any conditions, or making any stipulations whatever as to the chiefship. From this time

forth, the Mackintoshes and the Macphersons continued seperate and independent clans,

although both were included under the general denomination of the clan Chattan.

At the Revolution, the Mackintoshes adhered to the new government, and as the chief

refused to attend the Viscount Dundee, on that nobleman soliciting a friendly interview

with him, the latter employed his old opponent, Macdonald of Keppoch, to carry off his

cattle. In the rebellions of 1715 and 1745, the Mackintoshes took a prominent part.

Lauchlan, 20th chief, was actively engaged in the '15, and was at Preston on the Jacobite

side.

Lauchlan died in 1731, without issue, when the male line of William, the 18th chief,

became extict. Lauchlan's successor, William Mackintosh, died in 1741. Angus, the brother

of the latter, the next chief, married Anne, daughter of Farquharson of Invercauld, a lady

who distinguished herself greatly inthe rebelion of 1745. When her husband was appointed

to one of the three new companies in Lord Loudon's Highlanders, raised in the beginning of

that year, Lady Mackintosh traversed the country, and, in a very short time, enlisted 97

of the 100 men required for a captaincy. On the breaking out of the rebellion, she was

equally energetic in favour of the Pretender, and, inthe absence of Mackintosh, she raised

two battalions of the clan for the prince, and placed them under the command of Colonel

Macgillivray of Dunn maglass. In 1715 the Mackintoshes mustered 1,500 men under Old

Borlum, but in 1745 scarcely one half of that number joined the forces of the Pretender.

She conducted her followers in person to the rebel army at Inverness, and soon after her

husband was taken prisoner by the insurgents, when the prince delivered him over to his

lady, saying that "he could not be in better security, or more honourably

treated".

At the battle of Culloden, the Mackintoshes were on the right of the Highland army, and in

their eagerness to engage, they were the first to attack the enemy's lines, losing their

brave colonel and other offices in the impetuous charge. On the passing of the act for the

abolition of the heritable jurisdications of 1747, Mackintosh claimed £5000 as

compensation for his hereditary office of steward of the lordship of Lochaber.

In 1812, Aeneas, the 23d laird of Mackintosh, was created a baronet. On his death, without

heirs male, Jan 21, 1820, the baronetcy expired, and his cousin, Alexander whose immediate

sires had settled in Canada, succeeded to the estate. Alexander dying with issue was

succeeded by his brother Angus, at whose death in 1833 Alexander, his son became

Mackintosh of Mackintosh, and died in 1861, his son Alexander Aeneas, now of Mackintosh,

succedded him as 27th chief of Mackintosh, and 22nd captain of clan Chattan.

The funerals of the chiefs of Mackintosh were always conducted with great ceremony and

solemnity. When Lauchlan Mackintosh, the 19th chief, died, in the end of 1703, his body

lay in state from 9th December that year till 18th January 1704, in Dalcross Castle (which

was built in 1620, and is a good specimen of an old baronial Scotch mansion, and has been

the residence of several chiefs), and 2000 of the clan Chattan attended his remains to the

family vault at Petty. Kepoch was present with 220 of the Macdonalds. Across the coffins

of the deceased chiefs are laid the sword of William, twenty-first of Mackintosh, and a

highly finished claymore, presented by Charles I before he came to the throne, to Sir

Lauchlan Mackintosh, gentleman of the bedchamber.

The principal seat of The Mackintosh is Moy Hall, near Inverness. The original castle, now

in ruins, stood on an island in Loch Moy.

The eldest branch of the clan Mackintosh was the family of Kellachy, a small estate in

Inverness-shire, acquired by them in the 17th century. Of this branch was the celebrated

Sir James Mackintosh. His father, Captain John Mackintosh, was the tenth in descent from

Allan, third son of Malcolm, tenth chief of the clan. Mackintosh of Kellachy, as the

appointment of captain of the watch to the chief of the clan in all his wars. |

|

Another account of the Clan

BADGE: Lus nam braoileag (vaccineum

vitis idaea) Red whortleberry.

SLOGAN: Loch Moidh!

PIBROCH: Cu’a’

Mhic an Tosaich.

Two

chief authorities support different versions of the origin of this famous

clan. Skene in his Highlanders of Scotland and in his later Celtic

Scotland, founding on a manuscript of 1467, takes the clan to be a

branch of the original Clan Chattan, descended from Ferchar fada, son of

Fearadach, of the tribe of Lorne, King of Dalriada, who died in the year

697. The historian of the clan, on the other hand, Mr. A. M. Mackintosh,

founding on the history of the family written about 1679 by Lachlan

Mackintosh of Kinrara, brother of the eighteenth chief, favours the

statement that the clan is descended from Shaw, second son of Duncan,

third Earl of Fife, which Shaw is stated to have proceeded with King

Malcolm IV. to suppress a rebellion of the men of Moray in 1163, and, as a

reward for his services, to have been made keeper of the Royal Castle of

Inverness and possessor of the lands of Petty and Breachley, in the

north-east corner of Inverness-shire, with the forest of Strathdearne on

the upper Findhorn. These, in any case, are the districts found in

occupation of the family in the fifteenth century, when authentic records

become available. The early chiefs are said to have resided in Inverness

Castle, and, possibly as a result, the connection of the family with that

town has always been most friendly. Two

chief authorities support different versions of the origin of this famous

clan. Skene in his Highlanders of Scotland and in his later Celtic

Scotland, founding on a manuscript of 1467, takes the clan to be a

branch of the original Clan Chattan, descended from Ferchar fada, son of

Fearadach, of the tribe of Lorne, King of Dalriada, who died in the year

697. The historian of the clan, on the other hand, Mr. A. M. Mackintosh,

founding on the history of the family written about 1679 by Lachlan

Mackintosh of Kinrara, brother of the eighteenth chief, favours the

statement that the clan is descended from Shaw, second son of Duncan,

third Earl of Fife, which Shaw is stated to have proceeded with King

Malcolm IV. to suppress a rebellion of the men of Moray in 1163, and, as a

reward for his services, to have been made keeper of the Royal Castle of

Inverness and possessor of the lands of Petty and Breachley, in the

north-east corner of Inverness-shire, with the forest of Strathdearne on

the upper Findhorn. These, in any case, are the districts found in

occupation of the family in the fifteenth century, when authentic records

become available. The early chiefs are said to have resided in Inverness

Castle, and, possibly as a result, the connection of the family with that

town has always been most friendly.

Shaw’s youngest son, Duncan, was killed

at Tordhean in 1190, in leading an attack upon a raiding party of

Isles-men under Donald Baan, who had ravaged the country almost to the

castle walls. Shaw, the first chief, died in 1179. His eldest son, Shaw,

was appointed Toisach, or factor, for the Crown in his district, and died

in 1210. His eldest son, Ferquhard, appeared in an agreement between the

Chapter of Moray and Alexander de Stryveline in 1234 as " Seneschalle

de Badenach." His nephew and successor, Shaw, acquired the lands of

Meikle Geddes and the lands and castle of Rait on the Nairn. He also

obtained from the Bishop of Moray a lease of the lands of Rothiemurcus,

which was afterwards converted into a feu in 1464. He married the daughter

of the Thane of Cawdor, and while he lived at Rothiemurcus is said to have

led the people of Badenoch in Alexander III.’s expedition against the

Norwegians. There is a tradition that, having slain a man, he fled to the

court of Angus Og of Islay, and as the result of a love affair with Mora,

daughter of that chief, had to flee to Ireland. Subsequently, however, he

returned, married Mora, and was reconciled to his father-in-law. In his

time a certain Gillebride took service under Ferquhard. From him are

descended the MacGillivrays of later days, who have always been strenuous

supporters of the Mackintosh honour and power. In keeping with his stormy

life, shortly after his marriage, Ferquhard was slain in an island brawl,

and his two children, Angus and a daughter, were brought up by their uncle

Alexander, their mother’s eldest brother.

During the minority of

Angus the family fortunes suffered from the aggressions of the Comyns. In

1230 Walter Comyn, son of the Justiciar of Scotland, had obtained the

Lordship of Badenoch, and he and his descendants seem to have thought the

presence of the Mackintoshes in the district a menace to their interests.

During the boyhood of Angus they seized his lands of Rait and Meikle

Geddes, as well as the castle of Inverness, all of which possessions

remained alienated from Clan Mackintosh for something like a hundred

years.

Angus took for his wife in

1291 Eva, only daughter of the chief of Clan Chattan, a race regarding

whose origin there has been much discussion. According to tradition he

received along with her the lands of Glenlui and Locharkaig in Lochaber,

as well as the chiefship of Clan Chattan. According to another tradition,

however, Eva had a cousin once removed, Kenneth, descended, like her, from

Muireach, parson of Kingussie, from whom he and his descendants took the

name of Macpherson or " Son of the Parson." It is through this

Kenneth as heir-male that the Macpherson chiefs have claimed to be the

chiefs of Clan Chattan.

Angus, sixth chief of the

Mackintoshes, was a supporter of King Robert the Bruce. He is said to have

been one of the chief leaders under Randolph, Earl of Moray, at the battle

of Bannockburn, and as a reward to have received the lands of Benchar in

Badenoch. Also, as a consequence of the fall of the Comyns, he is

understood to have come again into possession of the! lands of Rait and

Meikie Geddes, as well as the keepership of the Castle of Inverness. From

younger sons of Angus were descended the Mackintoshes or Shaws of

Rothiemurcus, the Mackintoshes of Dalmunzie, and the Mackintoshes in Mar.

He himself died in 1345.

His son William, the

seventh chief, seems to have been almost immediately embroiled in a great

feud with the Camerons, who were in actual occupation of the lands of

Locharkaig. Mackintosh endeavoured to secure his possession of these old

Clan Chattan lands by obtaining a charter from his relative John of Isla,

afterwards Lord of the Isles, who had been made Lord of Lochaber by Edward

Baliol in 1335 and afterwards by a charter from David II. in 1359; but the

Camerons continued to hold the lands, and all that Mackintosh ever really

possessed of them was the grave in which he was buried in 1368, on the top

of the island of Torchionan in Locharkaig, where it is said he had

wistfully spent Christmas for several years. From a natural son of this

chief were descended the Mackintoshes or MacCombies of Glenshee and

Glenisla.

Lachlan, William’s son by

his first wife, Florence, daughter of the Thane of Cawdor, was the chief

at the time of the clan’s most strenuous conflicts with the Camerons. In

1370 or 1386, four hundred of the Camerons raided Badenoch. As they

returned with their booty they were overtaken at Invernahaven by a

superior body under the Mackintosh chief. A dispute, however, arose in the

ranks of Clan Chattan, the Macphersons claiming the post of honour on the

right wing, as representatives of the old Clan Chattan chiefs, while

Davidson of Invernahaven claimed it as the oldest Cadet. Mackintosh

decided in favour of Davidson; the Macphersons in consequence withdrew

from the field, and as a result the Mackintoshes and Davidsons were all

but annihilated. Tradition runs that in these straits Mackintosh sent a

minstrel to the Macpherson camp, who in a song taunted the Macphersons

with cowardice. At this, Macpherson called his men to arms, and, attacking

the Camerons, defeated and put them to flight.

Closely connected with this

event appears to have been the famous clan battle before King Robert III.

on the North Inch at Perth in 1396. According to some authorities this

battle was between Clan Davidson and Clan Macpherson, to settle the brawls

brought about by their rival claims to precedency. The weight of evidence,

however, appears to favour the belief that the battle was between Clan

Chattan and Clan Cameron. The incident is well known, and is recorded in

most of the Scottish histories of the following and later centuries. It

has also been made famous as an outstanding episode in Sir Walter Scott’s

romance The Fair Maid of Perth. On a Monday morning near the end of

September, thirty champions from each clan faced each other within

barriers on the North Inch. Robert III. was there with his queen and

court, while round the barriers thronged a vast crowd of the common people

from near and far. Before the battle began it was discovered that Clan

Chattan was one man short, and it seemed as if the fight could not take

place; but on the chief calling for a substitute, and offering a reward,

there sprang into the lists a certain Gow Chrom, or bandy-legged smith of

Perth, known as Hal o’ the Wynd. The battle then began, and was fought

with terrific fury till on one side only one man survived, who, seeing the

day was lost, sprang into the Tay and escaped. On the victorious side

there were eleven survivors, among whom Hal o’ the Wynd was the only

unwounded man. It is said he accompanied Clan Chattan back to the

Highlands, and that his race is represented by the Gows or Smiths, who

have been ranked as a sept of Clan Chattan in more recent times.

For a generation after this

combat the feud between the Mackintoshes and the Camerons seems to have

remained in abeyance.. In 1430, however, it broke out again, and raged

intermittently till well on in the seventeenth century.

Lachlan, the eighth chief,

died in 1407. His wife was Agnes, daughter of Hugh Fraser of Locrat, and

their son Ferquhard held the chiefship for only two years. He appears to

have been slothful and unwarlike, and was induced to resign his birthright

to his uncle Malcolm, reserving to himself only Kyllachy and Corrivory in

Strathdearn, where his descendants remained for a couple of centuries.

Malcolm, the uncle who in

this way succeeded as tenth chief, was a son of the seventh chief,

William, by his second wife, daughter of Macleod of the Lewis. He was a

short, thickset man, and from these characteristics was known as Malcolm

Beg. Two years after his succession, Donald of the Isles, in prosecution

of his claim to the Earldom of Ross, invaded the north of Scotland. Of the

mainland chiefs who joined his army Mackintosh and Maclean were the most

important, and at the great battle of Harlaw, north of Aberdeen, where the

Highland army was met and defeated by the Earl of Mar and the chivalry of

Angus and Mearns, both of these chiefs greatly distinguished themselves.

Maclean fell in the battle, as also did many of the Mackintoshes,

including James, laird of Rothiemurcus, son of Shaw, who was leader of

Clan Chattan in the lists at Perth; but the Mackintosh chief himself

appears to have escaped, and there is a tradition that at a later day he

conducted James I. over the field of battle. There is also a tradition

that, for yielding the honour of the right wing to the Maclean chief in

the attack, Mackintosh was granted by Donald of the Isles certain rights

in the lands of Glengarry.

It was in the time of this

chief that the Mackintoshes finished their feud with the Comyns. During

the lawless times under Murdoch, Duke of Albany, Alexander Comyn is said

to have seized and hanged certain young men of the Mackintoshes on a

hillock near the castle of Rait. Mackintosh replied by surprising and

slaying a number of the Comyns in the castle of Nairn. Next the Comyns

invaded the Mackintosh country, besieged the chief and his followers in

their castle in Loch Moy, and proceeded to raise the waters of the loch by

means of a dam, in order to drown out the garrison. One of the latter,

however, in the night-time managed to break the dam, when the waters

rushed out, and swept away a large part of Comyn’s besieging force

encamped in the hollow below. Thus foiled, the Comyns planned a more

crafty revenge. Pretending a desire for peace, they invited the chief men

of the Mackintoshes to a feast at Rait Castle. The tradition is that the

Comyn chief made each of his followers swear secrecy as to his design. It

happened, however, that his own daughter had a Mackintosh lover, and she

took the opportunity to tell the plot to a certain grey stone, when she

knew her lover was waiting for her on the other side of it. As a result

the Mackintoshes came to the feast, where each one found himself seated

with a Comyn on his right hand. All went well till the moment for the

murderous attack by the Comyns was all but reached, when Mackintosh

suddenly took the initiative, and gave his own signal, whereupon each

Mackintosh at the board drew his dirk and stabbed the Comyn next him to

the heart. The Comyn chief, it is said, escaped from the table, and,

guessing that the secret had been revealed by his daughter, rushed, weapon

in hand, to her apartment. The girl sought escape by the window, but, as

she hung from the sill, her father appeared above, and with a sweep of his

sword severed her hands, whereupon she fell into the arms of her

Mackintosh lover below. Whatever were the details of the final overthrow

of the Comyns, the Mackintosh chief in I442 established his right

to the lands of which his family had so long been deprived, and secured a

charter of them from Alexander de Seton, Lord of Gordon. The Mackintosh

chief was also, as already mentioned, restored to his position as

constable of the castle of Inverness by James I. in 1428. He

defended the castle in the following year against Alexander, Lord of the

Isles, when the latter burned Inverness, and, when the king pursued and

defeated the Island Lord in consequence in Lochaber, the issue is said to

have been largely brought about by the Mackintoshes and Camerons taking

part on the side of the king against their former ally.

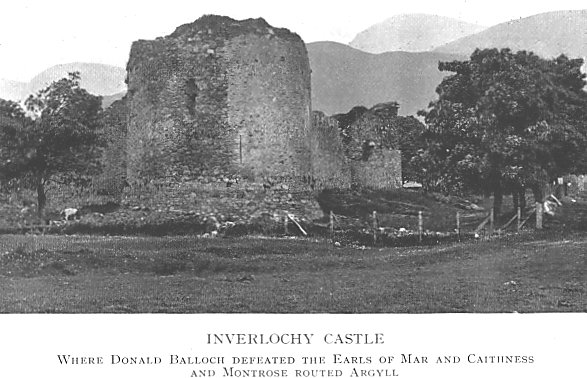

In 1431 the tables

were turned. The royal army under the Earls of Mar and Caithness was

defeated at Inverlochy by Donald Balloch, a cousin of Alexander of the

Isles, who forthwith proceeded to devastate the lands of Clan Chattan and

Clan Cameron for their desertion of him. For his loyalty Mackintosh

obtained from the king certain lands in Glen Roy and Glen Spean.

Though the Mackintoshes and

the Camerons fought on the same side in this battle they were not really

friends. There is a tradition that in the following year the Camerons made

a raid upon Strathdearn, and that the Mackintoshes fought and all but

exterminated a sept of them in a church on Palm Sunday.

Afterwards, when the Lord

of the Isles was made Justiciar of the North of Scotland, he set the

Mackintoshes against the Camerons, and though the latter were victorious

in a conflict at Craigcailleach in 1441, when one of Mackintosh’s

sons was slain, in the end Donald Dhu, the Cameron chief, was forced to

flee to Ireland, and his lands were forfeited for a time.

Malcolm Beg lived to an

extreme old age. In his time a number of septs came into’ the clan,

including the MacQueens, Clan Andrish, and Clan Chlearich, while his

second son Alan was the progenitor of the Kyllachy branch of the clan. One

of the last events of his life was a brush with the Munroes. On returning

from a raid in Perthshire, the latter were driving their booty through the

Mackintosh country, when they were stopped by the demand of Malcolm, a

grandson of the chief, that they should deliver up not only the usual

share in name of toll, but the whole of their booty. Munro thereupon

refused to pay anything, but at Clachnaharry, beyond the River Ness, he

was overtaken, and a bloody battle took place in which young Mackintosh

was slain, and Munro, tutor of Fowlis, was left for dead on the field.

Malcolm Beg’s eldest son

Duncan, the eleventh chief, who succeeded in 1464, was in favour with King

James IV., and devoted himself largely to securing his family possessions

by means of charters from the Crown and other superiors. But though

Duncan, the chief, was a peace-lover, his son Ferquhard was not. He joined

Alexander of Lochalsh, nephew of John of the Isles, in his attempt to

regain the earldom of Ross, and in the course of the attempt stormed the

castle of Inverness, obtaining possession by means of a "sow"

and by sapping. After ravaging the Black Isle, they proceeded to the

MacKenzies’ country, where they were surprised by the chief, and utterly

routed at the battle of Blair-na-Park, with the result that the Lord of

the Isles was finally forfeited and Ferquhard Mackintosh imprisoned in

Edinburgh Castle and in the castle of Dunbar till after the battle of

Flodden.

After his father’s death

in 1496, Ferquhard in prison had his affairs managed by his cousin

William, who ably defended the Mackintosh lands against raids of the

Camerons, Macgregors, and Macdonalds of Glencoe, and who was finally

infefted in the Mackintosh lands and chiefship, and succeeded to them on

the death of Ferquhard without male issue. Meanwhile, during his long

imprisonment, Ferquhard proved his ability in another way by compiling a

history of his clan. When he was set free after Flodden, in 1513, he was

received on the haugh at Inverness by eighteen hundred of his clansmen,

but he died in the following year.

The marriage of William,

who succeeded as thirteenth chief in 1514, was characteristic of the time.

In 1475 the Earl of Huntly had granted his father the marriage of the

sisters MacNaughton or MacNiven, co-heiresses of Dunachton, on condition

of receiving a bond of manrent. Lachlan’s son William was accordingly

married to the elder heiress, with the result that for the next hundred

years the Mackintosh chiefs were styled "of Dunachton."

William, however, had no

children, and his brother Lachlan was unmarried. Accordingly, his cousin,

John Ruaidh, who was next heir, proceeded to hasten his fortune. Learning

that the chief lay sick at Inverness, he entered the house and murdered

him in May, 1515. The assassins, however, were pursued through the north

by another cousin, Dougal Mhor, and his son Ferquhard, and finally

overtaken and executed in Glenness.

William’s brother,

Lachlan, who succeeded as fourteenth chief, had a similar fate. First

Dougal Mhor set up a claim to the chiefship, having seized the castle of

Inverness, but he was slain with his two sons when the castle was

recaptured for the king. Next a natural son of the chief’s elder

half-brother took to evil courses, and murdered the chief while hunting on

the Findhorn.

Lachlan Mackintosh had been

married to the daughter of Sir Alexander Gordon of Lochinvar and Jean,

sister of the first Earl of Cassillis, who was mother also of James IV.’s

natural son, the Earl of Moray; and on the death of Lochinvar at Flodden,

the son of Mackintosh quartered the Lochinvar arms with his own. This son,

William, was an infant when he succeeded to the chiefship, and during his

minority Hector, a natural son of Ferquhard, twelfth chief, by a Dunbar

lady, was chosen as captain by the clan. Fearful for the safety of the

infant chief, his next-of-kin, the Earl of Moray removed him with his

mother to his own house, where he caused the latter to marry Ogilvie of

Cardell. In reply, Hector Mackintosh raided the lands belonging to Moray

and the Ogilvies, and slew twenty-four of the latter, as a result of which

his brother William and others were hanged by Moray at Forres, and he

himself, having fled to the south, was assassinated by a monk of St.

Andrews.

It was now Queen Mary’s

time, and in the person of William, the young fifteenth chief, the most

famous tragedy in the history of the Mackintosh family was to take place.

The young chief appears to have been well educated, and distinguished by

his spirit and enlightenment. On the death of his early friend the Earl of

Moray, his most powerful neighbour became George, fourth Earl of Huntly.

This nobleman at first acted as his very good friend, and on the other

hand was supported by Mackintosh in some of his chief undertakings,

notably the expedition to replace Ranald Gailda in possession of his

father’s chiefship in Moidart, which had been seized by the notorious

John Muydertach—the expedition which led to the battle of Kinlochlochie,

in which the Macdonalds and the Frasers all but exterminated each other.

But on Huntly becoming feudal superior of most of the Clan Chattan lands,

trouble appears to have sprung up between him and his vassal. First, the

earl deprived Mackintosh of his office of Deputy Lieutenant, as a

consequence of the latter’s refusal to sign a bond of manrent. Then

Lachlan Mackintosh, son of the murderer of the chief’s father, though

the chief had bestowed many favours upon him, brought an accusation

against his chief of conspiring to take Huntly’s life. Upon this excuse

the earl seized Mackintosh, carried him to Aberdeen, and in a court packed

with his own supporters, had him condemned to death. The sentence would

have been carried out on the spot had not Thomas Menzies, the Provost,

called out his burghers to prevent the deed. Huntly, however, carried his

prisoner to his stronghold of Strathbogie, where he left him to his lady

to deal with, while he himself proceeded to France with the Queen Dowager,

Mary of Guise. Mackintosh was accordingly beheaded on 23rd August, 1550.

Sir Walter Scott, following tradition,

invests the incident with his usual romance. Mackintosh, he says, had

excited the Earl’s wrath by burning his castle of Auchendoun, and

afterwards, finding his clan in danger of extermination through the Earl’s

resentment, devised a plan of obtaining forgiveness. Choosing a time when

the Earl was absent, he betook himself to the Castle of Strathbogie, and,

asking for Lady Huntly, begged her to procure him forgiveness. The lady,

Scott proceeds, declared that Mackintosh had offended Huntly so deeply

that the latter had sworn to make no pause till he had brought the chief’s

head to the block. Mackintosh replied that he would stoop even to this to

save his father’s house, and, as the interview took place in the kitchen

of the castle, he knelt down before the block on which the animals for the

use of the garrison were broken up, and laid his neck upon it. He no doubt

thought to move the lady’s pity by this show of submission, but instead

she made a sign to the cook, who stepped forward with his cleaver, and at

one stroke severed Mackintosh’s head from his body.

The historian of Clan Mackintosh points out

the flaw in this story, the burning of Auchendoun not having taken place

till forty-three years later, at the hands of William, a grandson of the

same name.

It is interesting to note how Mackintosh

was indirectly avenged. Four years later Huntly was sent by the Queen

Regent to repress John Muydertach and Clan Ranald. Chief among the

Highland vassals upon whom he must rely were Clan Chattan; but, knowing

the feelings cherished by the clansmen against himself, he thought better

of the enterprise and abandoned it; upon which the Queen, greatly

displeased, deprived him of the Earldom of Moray and Lordship of

Abernethy, and condemned him to five years’ banishment, which was

ultimately commuted to a fine of £5,000.

But Huntly was to be still further punished

for his deed. Lachlan Mor, the son of the murdered chief, finished his

education in Edinburgh, and was a member of Queen Mary’s suite, when in

1562 she proceeded to the north to make her half-brother Earl of Moray.

This proceeding was highly resented by Huntly, who regarded the earldom as

his own, and who called out his vassals to resist the infeftment. When

Mary reached Inverness Castle she was refused admittance by Alexander

Gordon, who held it for Huntly. At the same time she learned that the

Gordons were approaching in force. Here was the opportunity of the young

Mackintosh chief. Raising his vassals in the neighbourhood, he undertook

the Queen’s protection till other forces arrived, when the castle was

taken and its captain hanged over the wall. Mackintosh also managed to

intercept his clansmen in Badenoch on their way to join the army of Huntly,

their feudal superior, and, deprived of their help, the Gordons retired

upon Deeside. Here, on 28th October, Huntly was defeated by Mary’s

forces at the battle of Corrichie, and died of an apoplectic stroke. It is

believed that the young chief, Lachlan Mor, afterwards fought on Mary’s

behalf at Langside.

In the faction troubles of

the north in the following years Mackintosh played a conspicuous part, and

at the battle of Glenlivet in 1594, commanding, along with Maclean, the

Earl of Argyll’s right wing, he almost succeeded in cutting off the Earl

of Errol and his men.

Lachlan Mor died in 1606.

Of his seven sons the eldest, Angus, married Jean, daughter of the fifth

Earl of Argyll, and their son, another Lachlan, becoming a gentleman of

the bedchamber to the prince, afterwards Charles I., received the honour

of knighthood in 1617, and is said to have been promised the earldom of

Orkney, but died suddenly in his twenty-ninth year. His second brother,

William, was ancestor of the Borlum branch of the clan, and his second

son, Lachlan of Kinrara, was writer of the MS. account of the family upon

which the earlier part of the modern history of the clan is based.

In the civil wars of

Charles I. the Mackintoshes took no part as a clan, on account of the

feeble health of William, the eighteenth chief, though large numbers of

Mackintoshes, Macphersons, and Farquharsons fought for the king under

Huntly and Montrose, while the chief himself was made Lieutenant of Moray

and Governor of Inverlochy Castle in the king’s interest.

At the same time, the

Macphersons, who, through Huntly’s influence, had been gradually, during

the last fifty years, separating themselves from the Mackintoshes, first

took an independent position in the wars of Montrose under their chief

Ewen, then tenant of Cluny, and proceeded to assert themselves as an

independent clan. A few years later, in the autumn of 1665, the dispute

with the Camerons over the lands of Glenlui and Locharkaig, which had

lasted for three hundred and fifty years, was brought to an end by an

arrangement in which Lochiel agreed to pay 72,500 merks. Still later, in

1688, the old trouble with the Macdonalds of Keppoch, who had persisted in

occupying Mackintosh’s lands in Glen Roy and Glen Spean without paying

rent, was brought to a head in the last clan battle fought in Scotland.

This was the encounter at Mulroy, in which the Mackintoshes were defeated,

and the chief himself taken prisoner.

Lachlan Mackintosh, the

twentieth chief, was head of the clan at the time of the Earl of Mar’s

rising in 1715, and with his clan was among the first to take arms for the

Jacobite cause. With his kinsman of Borlum he marched into Inverness,

proclaimed King James VIII., and seized the public money and arms, and he

afterwards joined Mar at Perth with seven hundred of his clan. The most

effective part of the campaign was that carried out by six regiments which

crossed the Forth and made their way into England under Mackintosh of

Borlum as Brigadier. And when the end came at Preston, on the same day as

the defeat at Sheriffmuir, the Mackintosh chief was among those forced to

surrender. He gave up his sword, it is said, to an officer named Graham,

with the stipulation that if he escaped with his life it should be

returned to him. In the upshot he was pardoned, but the holder of the

sword forgot to give it back. A number of years later the officer was

appointed to a command at Fort Augustus, when the sword was demanded by

the successor of its previous owner, who declared that if it were not

given up he would fight for it. The weapon, however, was then handed back

without demur. This sword is a beautiful piece with a silver hilt, which

was originally given to the Mackintosh chief by Viscount Dundee. It is

still preserved at Moy Hall, and is laid on the coffin of the chief when

he goes to his burial. For his part in Mar’s rising Lachlan Mackintosh

received a patent of nobility from the court at St. Germains.

Angus, the twenty second

chief, was head of the clan when Prince Charles Edward raised his standard

in 1745. In the previous year he had been appointed to command a company

of the newly-raised Black Watch, and his wife, the energetic Anne,

traversing the country, it is said, in male attire, had by her sole

exertions in a very short time raised the necessary hundred men, all but

three. She was a daughter of Farquharson of Invercald and was only twenty

years of age. Though hard pressed, Mackintosh kept his military oath. Lady

Mackintosh, however, raised two battalions of the clan, and it was these

battalions, led by young MacGillivray of Dunmaglass, who covered

themselves with glory in the final battle at Culloden. There, charging

with sword and target, they cut to pieces two companies of Burrel’s

regiment and lost their gallant leader, with several other officers and a

great number of men.

A few weeks before the

battle the Prince was sleeping at Moy Hall, when word was brought that

Lord Loudoun was bringing a force from Inverness to secure him. Like an

able general, Lady Mackintosh sent out the smith of Moy, with four other

men, to watch the road from Inverness. When Lord Loudoun’s force

appeared, these men began firing their muskets, rushing about, and

shouting orders to imaginary Macdonalds and Camerons, with the result that

the attacking force thought it had fallen into an ambush, and, turning

about, made at express speed for Inverness. The incident was remembered as

the Rout of Moy. A few days afterwards Charles himself entered Inverness,

where, till Culloden was fought, he stayed in the house of the Dowager

Lady Mackintosh.

The battle of Culloden may

be said to have ended the old clan system in Scotland. The line of the

Mackintosh chiefs, however, has come down to the present day. AEneas, the

twenty-third, was made a baronet by King George III. Before his death in

1820 he built the chief’s modern seat of Moy Hall, entailed the family

estates on the heir-male of the house, and wrote an account of the history

of the clan.

The tradition known as the

Curse of Moy, which was made the subject of a poem by Mr. Morrit of Rokeby,

included in Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, refers

particularly to this period, when from 1731 till 1833 no thief of

Mackintosh was succeeded by a son. The story is of a maiden, daughter of a

Grant of Urquhart, who rejected the suit of a Mackintosh chief. The latter

seized her, her father, and her lover, Grant of Alva, and imprisoned them

in the castle in Loch Moy. By her tears she prevailed upon Mackintosh to

allow one of his prisoners to escape, but when, at her father’s

entreaty, she named her lover, Mackintosh, enraged, had them both slain

and placed before her. In consequence she became mad, wandered for years

through Badenoch, and left a curse of childlessness upon the Mackintosh

chiefs. The drawbacks to the story are that Moy was not the seat of the

Mackintosh chiefs in early times, and that there were no Grants of

Urquhart.

Alfred Donald, the

twenty-eighth and present chief, is one of the best known and best liked

heads of the Highland clans, one of the best of Highland landlords, and

one of the most public-spirited men in the country. At his beautiful seat

of Moy Hall he frequently entertained the late King Edward, and his grouse

moors are the best-managed and most famous in Scotland. His only son,

Angus Alexander, was among the first to go to the Front in the great war

of 1914, where he was severely wounded in one of the earlier engagements.

He was afterwards secretary to the Duke of Devonshire when Governor

General of Canada, and married one of the Duke’s daughters, but died in

the following year. The Mackintosh is one of the most enthusiastic

upholders of Highland traditions, and, in view of his own family’s most

romantic story, it will be admitted that he has the best of all reasons

for his enthusiasm.

Septs of Clan MacKintosh:

Adamson, Ayson, Clark, Clerk, Clarkson, Crerar, Combie, Doles, Dallas,

Esson, Elder, Glennie, Glen, Hardy, MacAndrew, MacAy, MacCardney,

MacChlerich, MacChlery, MacCombe, MacCombie, MaComie, M'Conchy, MacFall,

Macglashan, MacHay, Machardy, M'Killican, Mackeggie, MacNiven, MacOmie,

MacPhail, Macritchie, MacThomas, Macvail, Niven, Noble, Paul, Ritchie,

Shaw, Tarrill, Tosh, Toshach.

Another account of the clan...

The

Mackintoshes claim descent from Shaw, second son of Duncan, Earl of Fife who accompanied

Malcolm IV on an expedition to Moray in 1160. He was rewarded with lands there and made

Constable of Inverness Castle. He was called "Mac-an-toisich mhic duibh" meaning

son of Thane. The Mackintoshes were later connected with the chiefship of Clan Chattan (a

confededation of clans claiming descent from the bailie of the Abbey of Kilchattan in

Bute) when Angus, 6th chief married Eva, the heiress of Clan Chattan in 1291. Lands in

Glenloy and Locharkaig in Lochnaber followed, which sparked off great feuds with the

Camerons and Gordons. The later additions of Glenroy and Glenspean led to trouble with the

MacDonalds of Keppoch neither of these disputes were settled until the late 17th century.

At the same time, the chiefship of Clan Chattan was in dispute between the chief of the

Macphersons and Mackintoshes. The matter was eventually settled in favour of the latter by

the Lord Lyon in 1692. During the revolution of 1688, the Mackintoshes followed the new

monarch but in the 1715 and 1745 Risings they supported the Stuart cause. Although in 1745

the chief Angus was actually in command of the Black Watch, his wife, the famous Colonel

Anne of Moy (a Farquharson of Invercauld) raised the clan for the Prince and it was her

strategy that was responsible for the Rout of Moy when 1500 government troops were put to

flight by half a dozen of Lady Mackintosh's retainers. Thereafter the Mackintosh line

dwindled and the senior lines died out. Following the death in 1938 of the 28th Chief the

chiefships of Clan Mackintosh and Clan Chattan were separated. The current chief has his

seat at Moy near Inverness and the chiefship of Clan Chattan although still vested in a

Mackintosh, is now with a different branch. The current chief of Clan Chattan lives in

Zimbabwe. |

Back |