|

The Macgilivrays were one of the oldest and most

important of the septs of clan Chattan, and from 1626, when their head, Ferquhard

MacAllister, acquired a right to the lands of Dunmaglass, frequent mention of them is

found in extant documents, registers, etc. Their ancestor placed himself and his posterity

under the protection of the Mackintoshes in the time of Ferquhard, fifth chief of

Mackintosh, and clan have ever distinguished themselves by their prowess and bravery. One

of them is mentioned as having been killed in a battle with the Camerons about the year

1330, but perhaps the best known of the heads of this clan was Alexander, fourth in

descent from the Ferquhard who acquired Dunmaglass. This gentleman was selected by Lady

Mackintosh to head her husband's clan on the side of Prince Charlie in the '45. He

acquitted himself with the greatest credit, but lost his life, as did all his officers

except three, in the battle of Culloden. In the brave but rash charge made by his

battalion against the English line, he fell, shot through the heart, in the centre of

Barrel's regiment. His body, after lying for some weeks in a pit where it had been thrown

with others by the English soldiers, was taken up by his friends and buried acorss the

threshold of the kirk of Petty. His brother William was also a warrior, and gained the

rank of captain in the old 89th regiment, raised about 1758. One of the three officers of

the Mackintosh battalion who escaped from Culloden was a kinsman of these two brothers -

Farquhar of Dalcrombie, whose grandson, Neil John M'Gillivray of Dunmaglass is the present

head of the clan.

The M'Gillivrays possessed at various times, besides Dunmaglass, the lands of

Aberchallader, Letterchallen, Largs, Faillie, Dalcrombie, and Davoit. It was in connection

with the succession to Faillie that Lord Ardmillan's well known decision was given in 1860

respecting the legal staus of a clan.

In a Gaelic lament for the slain at Culloden the MacGillivrays are spoken of as:

"The warlike race,

The gentle, vigorous, flourishing,

Active, of great fame, beloved,

The race that will not wither, and has descended

Long from every side,

Excellent MacGillivrays of the Doune".

Another account of the Clan

BADGE: Los nam braoileag (vaccineum

vitis idea) red whortle berry.

SLOGAN: Loch Moy, or Dunma’glas.

PIBR0CH: Spaidsearachd

Chlann Mhic Gillebhràth.

MR

GEORGE BAIN, the historian of Nairnshire, in one of his many interesting

and valuable brochures, The Last of Her Race, recounts a tradition

of the battle of Culloden which was handed down by members of an old

family of the district, the Dallases of Cantray. At the time of the last

Jacobite rising, it appears, two beautiful girls lived in the valley of

the Nairn. At Clunas, a jointure house of Cawdor, high in the hills, lived

Elizabeth Campbell, daughter of Duncan Campbell of Clunas. She was a

highly accomplished young woman, having been educated in Italy, whither

her father had fled after taking part in the Jacobite rising of 1715, and

she was engaged to be married to young Alexander MacGillivray, chief of

the clan of that name. Anna Dallas of Cantray, on the other hand, was a

daughter of the chief of the Dallases, and her home was the old house of

Cantray in the valley of the Nairn below. She likewise was engaged to be

married, and her fiancé was Duncan Mackintosh of Castleledders, a near

relative of the Mackintosh chief. These were said to be the two most

beautiful women in the Highlands at the time. Old Simon, Lord Lovat, who,

with all his wickedness, was well qualified to criticise, is said to have

declared that he did not know which was the more dangerous attraction,

" the Star on the Hilltop," or "the Light in the

Valley." There was doubtless something of a rivalry between the two

young women. Now, Angus, chief of the Mackintoshes, was on the Government

side, and in his absence his wife, the heroic Lady Mackintosh, then only

twenty years of age, had raised her husband’s clan for Prince Charles.

On the eve of the battle of Culloden it was thought that Mackintosh of

Castleledders might lead the clan in the impending battle. That night,

however, Elizabeth Campbell told her fiancé that unless he led the

Mackintosh clan for the Prince on the morrow, he need come to see her no

more. The young fellow accordingly hurried off to Moy Hall, and told

"Colonel " Anne, as the pressmen of that time called Lady

Mackintosh, that the MacGillivrays would not fight on the morrow unless he

was in command of the whole Clan Mackintosh. Now the MacGillivrays were

only a sept of the clan, though the mother of Dunmaglass was descended

from the sixteenth Mackintosh chief, but they made a considerable part of

the strength of Clan Mackintosh. Lady Mackintosh, therefore, became

alarmed, sent for Castleledders, and begged him for the sake of the cause

which was at stake to forego his right, as nearest relative of its chief.

to lead the clan on this occasion. Moved by her entreaty he agreed, with

the words, " Madam, at your request, I resign my command, but a

Mackintosh chief cannot serve under a MacGillivray"; and accordingly

he went home and took no part in the battle. Next day, it is said, the

heart of Elizabeth Campbell was filled with pride when she saw her

sweetheart, Alexander MacGillivray, yellow-haired young giant as he was,

marshalling the Mackintoshes 700 strong in the centre of the Prince’s

army, and it is said she rode on to the field to congratulate him. The

Prince noticed her, and asked who she was, and, on being told, remarked

that MacGillivray was a lucky fellow to have so beautiful and so spirited

a fiancée. MR

GEORGE BAIN, the historian of Nairnshire, in one of his many interesting

and valuable brochures, The Last of Her Race, recounts a tradition

of the battle of Culloden which was handed down by members of an old

family of the district, the Dallases of Cantray. At the time of the last

Jacobite rising, it appears, two beautiful girls lived in the valley of

the Nairn. At Clunas, a jointure house of Cawdor, high in the hills, lived

Elizabeth Campbell, daughter of Duncan Campbell of Clunas. She was a

highly accomplished young woman, having been educated in Italy, whither

her father had fled after taking part in the Jacobite rising of 1715, and

she was engaged to be married to young Alexander MacGillivray, chief of

the clan of that name. Anna Dallas of Cantray, on the other hand, was a

daughter of the chief of the Dallases, and her home was the old house of

Cantray in the valley of the Nairn below. She likewise was engaged to be

married, and her fiancé was Duncan Mackintosh of Castleledders, a near

relative of the Mackintosh chief. These were said to be the two most

beautiful women in the Highlands at the time. Old Simon, Lord Lovat, who,

with all his wickedness, was well qualified to criticise, is said to have

declared that he did not know which was the more dangerous attraction,

" the Star on the Hilltop," or "the Light in the

Valley." There was doubtless something of a rivalry between the two

young women. Now, Angus, chief of the Mackintoshes, was on the Government

side, and in his absence his wife, the heroic Lady Mackintosh, then only

twenty years of age, had raised her husband’s clan for Prince Charles.

On the eve of the battle of Culloden it was thought that Mackintosh of

Castleledders might lead the clan in the impending battle. That night,

however, Elizabeth Campbell told her fiancé that unless he led the

Mackintosh clan for the Prince on the morrow, he need come to see her no

more. The young fellow accordingly hurried off to Moy Hall, and told

"Colonel " Anne, as the pressmen of that time called Lady

Mackintosh, that the MacGillivrays would not fight on the morrow unless he

was in command of the whole Clan Mackintosh. Now the MacGillivrays were

only a sept of the clan, though the mother of Dunmaglass was descended

from the sixteenth Mackintosh chief, but they made a considerable part of

the strength of Clan Mackintosh. Lady Mackintosh, therefore, became

alarmed, sent for Castleledders, and begged him for the sake of the cause

which was at stake to forego his right, as nearest relative of its chief.

to lead the clan on this occasion. Moved by her entreaty he agreed, with

the words, " Madam, at your request, I resign my command, but a

Mackintosh chief cannot serve under a MacGillivray"; and accordingly

he went home and took no part in the battle. Next day, it is said, the

heart of Elizabeth Campbell was filled with pride when she saw her

sweetheart, Alexander MacGillivray, yellow-haired young giant as he was,

marshalling the Mackintoshes 700 strong in the centre of the Prince’s

army, and it is said she rode on to the field to congratulate him. The

Prince noticed her, and asked who she was, and, on being told, remarked

that MacGillivray was a lucky fellow to have so beautiful and so spirited

a fiancée.

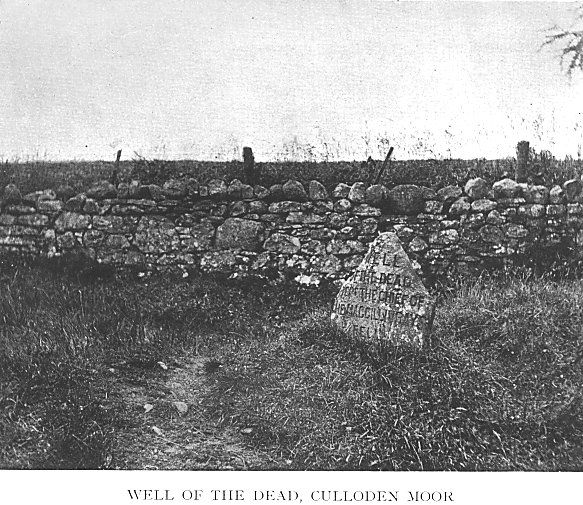

Alas! a few hours later

young MacGillivray lay dying on the field. His last act, it is said, was

to help a poor drummer boy, whom he heard moaning for water, to the spring

which may still be seen at hand, and which is known to this day from the

fact as MacGillivray’s or the Dead Men’s Well. There he was found next

morning, his body stripped by the cruel Hanoverian soldiery, and it was

remarked what a beautiful figure of a young fellow he was. His body was

buried in the Moss where it lay, and six weeks later, after the English

had gone, when it was taken up, to be buried under the doorstep of the

kirk of Petty, people marvelled that it was still fresh and beautiful, and

that his wounds bled afresh.

Young as he was, Dunmaglass

had played his part splendidly in the battle. In the furious attack which

he led, the Mackintoshes almost annihilated the left wing of the Duke of

Cumberland’s army, and before he fell, with four officers of his clan,

MacGillivray himself encountered the commander of Barrel’s regiment, and

struck off some of his fingers with his broadsword. Next day, in the

streets of Inverness, this commander met a private soldier wearing

MacGillivray’s finely embroidered waistcoat, and, recognising it,

indignantly stopped the man, and ordered him to take it off. "Yesterday,"

he said, "on the field of battle I met the brave man who wore that

waistcoat, and it shall not be thus degraded." The waistcoat,

however, must afterwards have been lost or again stolen, for it is

recorded that it was observed exposed for sale in the window of a tailor

in Inverness.

Such was the family

tradition of the Dallases accounting for the fact that Dunmaglass led the

Mackintoshes at Culloden. But it must be remembered that he had seen

foreign service and had led the clan from the first, meeting the Prince at

Stirling with seven hundred men at his back on Charles’s return from

England, and commanding the regiment at the battle of Falkirk.

Meanwhile poor Elizabeth

Campbell, though her ambition had been gratified, was stricken to the

heart. Her big beardless boy lover—he was six feet five inches in height—with

light yellow hair, and a complexion as fair and delicate as any lady’s—was

dead, and he would indeed come to see her no more. A few months afterwards

she died of a broken heart. On the other hand, Anna Dallas had lost her

father. The chief of the Dallases was killed in the battle by a bullet

through the left temple. But she married her lover, Duncan Mackintosh of

Castleledders, and their son, Angus, by and by, succeeded as chief of the

Mackintoshes and the great Clan Chattan.

Of the MacGillivrays it may

be said, as was said of the great house of Douglas, that no one can point

to their first mean man. A tradition recorded by Browne in his History

derives the name from Gillebride, said to have been the father of the

great Somerled. But of the origin of the family nothing is known

definitely except that so far back as the thirteenth century the ancestor

of the race, one Gilbrai, Gillebreac, or Gillebride, placed himself and

his posterity under the protection of Ferquhard, the fifth Mackintosh

chief. The name MacGillivray probably means either "the son of the

freckled lad," or "the son of the servant of St. Bride." In

any case, for some five centuries, down to the last heroic onset on the

field of Culloden, just referred to, the MacGillivrays faithfully and

bravely followed the "yellow brattach," or standard, of the

Mackintoshes, to whom they had allied themselves on that far-off day. An

account of the descent of the race of Gilbrai is given in the history of The

Mackintoshes and Clan Chattan by Mr. A. M. Mackintosh—one of the

best and most reliable of the Highland clan histories extant.

Mr. Mackintosh quotes the

Rev. Lachlan Shaw’s History of the Province of Moray, the Kinrara

Manuscript of 1679, and various writs and documents in the Mackintosh

charter-chest at Moy Hall, and his account is not only the latest but the

most authoritative on the subject.

The first of Gilbrai’s

descendants to attain mention is Duncan, son of Allan. This Duncan married

a natural daughter of the sixth Mackintosh chief, and his son Ivor was

killed at Drumlui in 1330. A hundred years later, about the middle of the

fifteenth century, the chief of the MacGillivrays appears to have been a

certain Ian Ciar (Brown). At any rate, when William, fifteenth chief of

the Mackintoshes, was infefted in the estate of Moy and other lands held

from the Bishop of Moray, the names of a son and two grandsons of this Ian

Ciar appear in the list of witnesses. Other Mackintosh documents show the

race to have been settled by that time on the lands of Dunmaglass (the

fort of the grey man’s son), belonging to the thanes of Cawdor. Ian Ciar

was apparently succeeded by a son, Duncan, and he again by his son

Ferquhar, who, in 1549, gave letters of reversion of the lands of

Dalmigavie to Robert Dunbar of Durris. Ferquhar’s son, again, Alastair,

in 1581 paid forty shillings to Thomas Calder, Sheriff-Depute of Nairn,

for " two taxations of his £4 lands of Domnaglasche, granted by the

nobility to the King." It was in his time, in 1594, that the

MacGillivrays fought in the royal army under the young Earl of Argyll at

the disastrous battle of Glenlivat. Alastair’s son, Ferquhar, appears to

have been a minor in 1607 and 1609, for in the former of these

years his kinsman Malcolm MacBean was among the leading men of Clan

Chattan called to answer to the Privy Council for the good behaviour of

Clan Chattan during the minority of Sir Lachlan Mackintosh its chief; and

in the latter year, when a great band of union was made at Termit, near

Inverness, between the various septs of Clan Chattan, responsibility for

the " haill kin and race of the Clan M’Illivray" was accepted

by Malcolm MacBean, Ewen M Ewen, and Duncan MacFerquhar, the last-named

being designated as tenant in Dunmaglass, and being probably an uncle of

young Ferquhar MacGillivray.

This Ferquhar, son of

Alastair, was the first to obtain heritable right to Dunmaglass, though

his predecessors had occupied the lands from time immemorial under the old

thanes of Cawdor and their later successors, the Campbells. The feu-contract

was dated 4th April, 1626, and the feu-duty payable was £16 Scots yearly,

with attendance on Cawdor at certain courts and

on certain occasions.

Ferquhar’s eldest son, Alexander,

died before his father, and in 1671 his three brothers, Donald, William,

and Bean MacGillivray, were put to the horn, with a number of other

persons, by the Lords of Justiciary for contempt of court; at the same

time Donald, who, three years earlier, had acquired Dalcrombie and

Letterchallen from Alexander Mackintosh of Connage, was designated tutor

of Dunmaglass, being probably manager of the family affairs for his father

and his brother, Alexander’s son.

Alexander MacGillivray had married

Agnes, daughter of William Mackintosh of Kyllachy, and his son Farquhar,

was in 1698 a member of the Commission against MacDonald of Keppoch. Three

years later he married Amelia Stewart. Farquhar, his eldest son and

successor, was a Captain in Mackintosh’s regiment in the Jacobite rising

of 1715, while the second son, William, was a Lieutenant in the same

regiment and was known as Captain Ban. Their kinsman, MacGillivray of

Dalcrombie, was also an officer, and, among the rank and file forced to

surrender at Preston, and executed or transported, were thirteen

Mackintoshes and sixteen MacGillivrays.

It was Alexander, eldest son of the

last-named Farquhar, who, having succeeded his father in 1740, commanded

the Mackintosh regiment and fell at Culloden as already related. Among

those who fell with him on that occasion was Major John Mor MacGillivray.

It was told of him that after the charge he was seen a gunshot past the

Hanoverian cannon and killed a dozen men with his broadsword while some of

the halberts were run through his body. Another clansman, Robert Mor

MacGillivray, kjlled seven of his enemies with the tram of a peat cart

before he was himself overpowered and slain.

The young chief, Alexander

MacGillivray, was succeeded by his next brother, William, who, in 1759,

became a captain in the 89th Regiment, raised by the Duchess of Gordon. He

served with that regiment, mostly in India, till it was disbanded in 1765.

His next brother, John, was a merchant at Mobile, and a loyalist colonel

in the American Revolution. With his help William added to his family

estate the lands of Faillie, and half of Inverarney, with Wester Lairgs

and Easter Gask, the two last having previously been held on lease.

His son, John Lachian MacGillivray,

succeeded not only to the family estates but to the property of his uncle,

Colonel John, the wealthy Mobile merchant. As a young officer in the 16th

Light Dragoons, he had been given to much extravagance, but on inheriting

his uncle’s money he was able to clear the estate of debt. At his death,

however, in 1852, he left no family, and the chiefship devolved on the

representative of Donald of Dalcrombie, the tutor of Dunmaglass in the

seventeenth century. The tutor’s grandson, Donald, was one of those

murdered in cold blood by the Hanoverian soldiery after Culloden, but his

son Farquhar, also an officer of the Mackintosh regiment, survived the

battle. He married Margaret, daughter of AEneas Shaw of Tordarroch, and it

was his son John who, in 1852, succeeded to Dunmaglass and the chiefship.

This succession was disputed by a

kinsman, the Reverend Lachlan MacGillivray, descended from William

MacGillivray of Lairgs, brother of Donald, the tutor, the question being

whether Donald, the tutor, or his brother William of Lairgs, had been the

elder. In 1857 the court decided in favour of Donald and his descendants.

Two years before this, however, John MacGillivray had died. He had been a

well-known man in Canada, where he was a member of the Legislative

Council. The eldest of his four sons, Neil John, found himself in

financial straits, and after selling Wester Lairgs and Easter Gask, took

steps to dispose of Dunmaglass itself, and the rest of the property which

had been possessed by his family from time immemorial. His eldest son,

John William, born in 1864, is the present chief of the MacGillivrays.

The ancient property of this family

lies about the sources of the river Farigaig in Stratherrick. When the

Thane of Cawdor, in 1405, procured an act incorporating all his lands in

Inverness and Forres into the shire of Nairn, Dunmaglass was part of the

territory included. It forms an oblique parallelogram about seven miles

long and sixteen square miles in extent. In "the forty-five" the

chief’s own followers numbered about eighty men.

Besides the family of Dunmaglass and

its following there was in the Island of Mull a sept of the MacGillivrays

which took its name from the residence of its head and was known as "Og

Beinn-na-gall." They were believed to have been descended from the

main stem in Lochaber, and to have been dispersed after the discomfiture

of Somerled, Lord of the Isles, in 1164. They were also known under the

name of MacAngus, or Maclnnes.

In the line of ancestors from whom

these island clansmen claimed descent was a certain Martin MacGillivray, a

parson of about the year 1640. This individual, according to Logan, author

of the letterpress of MacIan’s Clans of the Scottish Highlands, was in

the habit of carrying a sword. Upon one occasion he happened to call on a

son of MacLean of Lochbuie for part of his stipend. The latter refused to

pay, and asked whether his visitor meant to enforce his demand with his

sword. "Rather than lose what is my due," answered MacGillivray,

" I shall use my weapon, and I am content to lose the money if you

can put my back to the wall." In the upshot, however, he quickly

brought his opponent to his knees, and the latter thereupon gave in, paid

the amount due, and declared that he liked well to meet a man who could

maintain his living by the sword.

Another anecdote of this house is told by the same

writer. At the battle of Sheriffmuir, in 1715, he says, the Laird of

Beinn-na-gall happened to stumble, whereupon a friend standing near,

thinking he was shot, cried out, "God preserve ye, MacGillivray!

" He was no doubt startled by the reply, " God preserve

yourself," exclaimed Beinn-na-gall, " I have at present no need

of His aid."

These island MacGillivrays or Maclnneses, however,

followed, not the chiefs of Clan Chattan, but the MacDougal Campbells of

Craignish, as their chiefs. Details regarding them are to be found in

Cosmo Innes’s Early Scottish History and in Skene’s Highlanders of

Scotland.

Septs of Clan MacGillivray: Gilory,

MacGillivour, MacGilroy, MacGilvra, MacGilvray, Macilroy, Macilvrae.

|