|

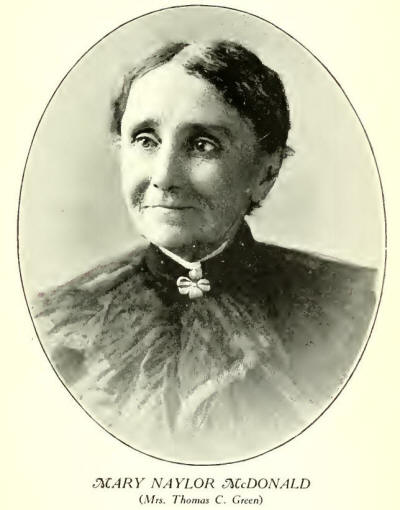

Mary Naylor McDonald, the oldest child of

Angus W. McDonald and Leacy Anne Naylor (his wife), was born in Romney,

Virginia, Dec. 27th, 1827, and named Mary for her father's mother and

Naylor for her mother's family. At quite an early age she was sent to a

school in Winchester taught by Madame Togno. At this school she was

taught both Latin and Greek; and I have often heard it related that she

translated the Greek Testament by the time she was twelve years old, her

father having promised as

a reward for that accomplishment that she

should study music.

She was of a most lovable and happy

disposition, full of vivacity, and possessed of a ready sympathy which

lent great charm to her manner. She was also very pretty, with a fair

complexion, brown hair and dark, greyish-blue eyes, which sparkled with

fun or filled with tears just as her mood or emotions prompted. She had

a lovely voice, too, which gave great pleasure to her friends and she

kept up her music—vocal as well as instrumental--until quite late in

life.

Mary lost her mother when about fifteen

years of age and was thus early brought to face responsibilities unusual

for so young a girl.

She was married April 27th, 1852, to

Thomas Claiborne Green, of Culpeper County, though at the time of their

marriage he was living in Charles Town, Jefferson County, Virginia. (At

that time there was no such State as "West Virginia"), engaged in the

practice of law. Surrounded by a delightful and congenial society with

children to bless their home, life flowed very smoothly and pleasantly

for several years.

Finally, one memorable morning at early

dawn, the little town where they lived was paralyzed with the rumor

which traveled with telephonic swiftness that the Arsenal at Harper's

Ferry, which was but a few miles distant, had been taken possession of

by a lot of men armed with pikes, some of them over six feet long, and

that these outlaws had gone into the houses of several of their friends

and neighbors in the night, taken them from their beds and had there now

with them in the Arsenal. Could

anything have been more startling to a quiet, orderly, Iittle Country

village? Her husband, Thos. C. Green, happened to be the Mayor of the

place at the time, and few more serious offenses than an occasional raid

by a negro of a hen roost, had been brought to his official notice. In a

little while the whole country shared with them all the startling

details of this dastardly invasion and the hitherto quiet village became

one of the historic localities in the great tragic drama that held the

stage in Northern Virginia for the four ensuing; years.

Everybody knows how the insurgents were

finally captured and lodged in the jail in Charles Town. Mary's husband

was not only Mayor at that eventful epoch, but he was also appointed by

the Commonwealth to defend John Brown. Naturally she heard much of the

whole business and when sentence was finally passed that he should be

hung Mary wanted to go off on a visit until the whole thing was over,

but finding that to be impossible she announced that she didn't want

anyone to tell her where the hanging would take place, or indeed

anything in connection with it. Not

that she had any sympathy whatever for the culprit, but she was very

tender-hearted and had no relish for suffering of any kind, much less

such a gruesome event at that. She couldn't help, however, knowing the

day it was to take place and in order to shut everything connected with

it from her knowledge, she retired to her room upstairs and closed all

the shades carefully, but when the sounds from the street made her aware

that numbers of people were passing the house she decided to go to the

attic where she hoped to get beyond the sound as well as the sight of

the passing crowds. The subdued

light of her star-chamber, as well as the perfect quiet, had the effect

of completely composing her agitated nerves—and if the facts could be

known with absolute certainty it is highly probable that she uttered a

prayer or two for the soul of the misguided creature who was about to be

launched into eternity—so after awhile the close atmosphere of her

apartment becoming oppressive, in an unwary moment, she threw open a

window—and behold! swinging in mid-air the body of the lawless invader.

If she had exercised the greatest care in

the selection of her vantage point, as well as the propitious moment,

she could not have been more successful. Not an object intervened

between the open window and the ghastly spectacle. With a scream of

horror she fell back from the sight and it was some time before she was

able to relate her experience, nor did she ever relish the distinction

of being the only lady of her acquaintance who had witnessed the famous

execution. It was not long after

that before the war came on in real earnest and her husband, having

always been an enthusiastic believer in State Sovereignty, was among the

first to enlist as a private in a volunteer company of his town, the "Bott's

Grays," and was mustered into the service of the Confederacy in the 2nd

Reg. Virginia Infantry, and was with that noble brigade when it received

its baptismal name of "Stonewall" at the first Manassa. He seems to have

borne a charmed life then as he did many times later, for, although he

passed through the war without a scratch, his clothing bore many marks

of shot and shell. Their sweet home

life was now broken up and Mary moved first to Winchester with her

little children and later to Richmond. Her husband remained in the ranks

for sometime but was finally induced by his friends to become a

candidate for the Legislature and although he was elected he invariable

joined his company again whenever there was a prospect of an engagement.

His colleagues said that they always knew when to expect a fight by

Green's seat being vacant. He had—in his character of free lance—an

amusing encounter with General Early when they were on the retreat from

Gettysburg. Mr. Green had dropped out of his regiment, which was

crossing a stream, and was carefully removing his shoes and other

articles of apparel before plunging into the water when General Early

rode up and, with his usual oath, demanded to know what he was doing out

of ranks, whereupon Mr Green politely insinuated that it was none of his

business. "Do you know that you are

addressing General Early, sir?' he retorted in irate tones.

*'Do you know that you are speaking to a

member of the Virginia Legislature?" returned Mr. Green, cooly

continuing his preparations. Mary

continued to live in Richmond until the close of the war, and I remember

an incident which occurred at the time of the surrender which was both

tragic and humorous in which Mr. Alex Marshall played a prominent part,

and although she knew that Richmond had been evacuated by the

Confederates, Mary still loyally clung to the hope of ultimate success.

About three o'clock in the afternoon of the

day of the surrender Mr. Marshall appeared at her house. She was passing

through the hall as he entered the door, and as his face wore such a

serious aspect, she exclaimed in alarmed tones: "Oh, Mr. Marshall, what

is the matter?" "Mary,'' he replied

hesitatingly, unwilling to impart such distressing tidings, "General Lee

has surrendered." "I don't believe

one word of it," she promptly returned, "and you just get right out of

this house if you have come to tell me such a thing as that."

And when he still continued to assert it she

just as peremptorily insisted upon his leaving the house, which he

finally did, with tears in his eyes, saying:

"To think that Angus' child should treat me

so." He from the pavement at the

foot of the steps and she in the doorway continued the conversation

until finally from that safe vantage point Mr. Marshall convinced her

that the melancholy news was only too true.

When all at last was over, like many another

family, they returned to find their home in Charles Town almost a wreck,

but with stout hearts and a still unshaken faith in God's mercy and

justice (though it had been severely jarred by the results of the war)

they both, Mary and her husband, went to work in good earnest to gather

up the fragments and pick up again the dropped stitches of their lives.

With her family of little children she necessarily had much to do in the

way of sewing and her intense delight when she became possessed of her

first sewing machine was almost pathetic. She frankly confessed that she

just had to stop her sewing several times during the day to thank her

Heavenly Father on her knees for the great invention which meant. so

much to womankind. Mr. Green, her

husband, resumed the practice of his profession until June, 1876, when

he was appointed by Gov. Jacobs to a seat on the Bench of the Court of

Appeals, to which he was twice re-elected, holding the position at the

time of his death, which occurred Dec. 1st, 1889, and the sentiments of

his colleagues, at a meeting which was held by them to take appropriate

action on his death, were expressed in the following tribute:

"He was one of the purest and ablest judges

that has ever adorned the bench of this State * * * * The

plaintiff and the defendant were to him as impersonal the letters of an

equation, and he applied himself to the solution of the questions before

him as if he were searching by known and inflexible mathematical

processes for an unknown quantity.

Truth was the object of his search and he followed it with unerring

judgment. No Judge, on any bench, ever gave such exhaustive research to

the salve number of cases, in proportion to those in which he wrote

opinions, as Judge Green. His

devotion to duty and respect for right and justice are universally

acknowledged and neither envy or malice ever called in question the

purity of his life or his impartiality in the performance of his public

duties. His nature was simplicity itself, confiding and loyal in his

friendships but firm and uncompromising in his convictions of right and

duty." Mary survived her husband

for twelve years and finally died at the home of her daughter, Mrs. V.

L. Perry, in Hyattsville, Md. A

notice of her death, which appeared at the time, said:

"Mrs. Green was a woman of fine intellectual

abilities, well fitted to be the wife of her distinguished husband, for

whose integrity of character and nobility of mind she had the deepest

admiration. She supplied the practical side to a great character, whose

child-like simplicity was one of his peculiar attractions; sympathizing

also with his intellectual life, following his political faith and

aiding and supporting him through a married life of almost forty years.

To unselfishness of life she united fidelity

to principle and duty; loyalty to the past, courage and hopefulness for

the future; fortitude, refinement, simplicity; an indomitable

truthfulness of character, a supreme tenderness of soul, a lovely and

gracious humour, the keenest wit. * * * * For more than fifty years she

Ient her energies and activity to work in the Church, Sunday School and

among the colored people, whom she always attached to her by her charity

and sweetness. In the last hours of

her life there was assuredly vouchsafed to her a vision of `rest.' It

was the last word she spoke." Five

children survived her. Mrs. John Porterfield, Mrs. Cruger Smith, Mrs. J.

E. Latimer and Mrs. V. L. Perry and one son, Thomas Claiborne Green. She

lost two children in infancy and a lovely daughter, Mary, about the age

of fifteen. |