|

Reminiscences.

[When I sent Kenneth some of the family sketches to read, his only

criticism was that he thought 'I ought to write Iess of the war

experiences and more of peaceful occupations. I proposed that he should

write his own sketch, and his "reminiscences" are an amusing commentary

on his own criticism.—(Ed.)]

Fifty years have passed since the first

things which this little sketch relates, happened, and as it is all from

my rather imperfect memory, there will doubtless appear statements

somewhat at variance with the facts touching the war operations around

Winchester and Lexington (Va.)

When the war broke out between the North

and South, our home was in Winchester, Va., on the Romney road, about a

mile from the centre of the town, and in a unique position for taking

observations as well as being exposed to the dangers usually surrounding

non-combatants.

At the very first, all the grown

brothers, Angus, Edward, William, Marshall and Woodrow, had ;one into

the conflict as Confederate soldiers, and with them our father also.

This left Mother in sole command with Harry, fourteen years old, as her

mails protector. At that early age, Harry believed and often said that

he, also, should be in the Confederate army; so he never allowed an

occasion to pass, when he or any of us was insulted or imposed upon by

the Yankee soldiers, that he did not resent it. Although

I was five years younger than Harry, I

was often with him. We were among the branches of one of Senator Mason's

cherry trees one day, and two Yankees stopped and ordered us to come

down. Harry at first refused, but when one of the soldiers raised his

gun, he changed his mind. When he reached the ground, one of the Yankees

struck him a heavy blow with his open hand, and received a very bloody

nose in return, but Harry finally got the worst of it, and as usual in

such encounters, we had to withdraw somewhat worsted. The Yankees would

always start trouble by asking us if we were "Secesh," meaning

Secessionists. The answer was always the same, that "we were." Then

invariably followed some insult or violence. I was asked this question

when I was alone one day, and gave the usual answer. The Yankee picked

me up by the feet and dipped me head foremost into the spring till the

water rose to my middle. I thought he was trying to drown me, but I can

see now that he was exasperated at my impudence and only meant to give

me a good scare.

It seemed to us, during these first years

of the war, that the Confederates never tried to hold Winchester, but

deliberately allowed the Yankees to take possession and lay up stores

and ammunition to be taken from them by sudden attacks, which seemed to

come at regular intervals. On one of these occasions, we saw by the

hurried movements of cavalry, wagons, artillery, etc., through our place

to and from the fort on a hill in the rear, to say nothing of the

serious looks on the soldiers' faces, that trouble was brewing. The next

morning about 9 o'clock, we heard cannon in the distance and immediately

\vent up on the roof of the house, and lay there watching for what might

happen. On a hill just across the Romney road, and not 400 yards from

us, a regiment of Federal cavalry was drawn up. All had fine black

horses and looked to be a perfect body of soldiers. They were armed and

equipped to the last detail, but we remarked to each other that they

must be concealing themselves for some sudden movement against the

Confederates. Less than fifty yards in front of them, there was a dense

thicket which completely hid them from view. Suddenly, a long line of

smoke and blaze burst from the thicket and about one-fourth of the

horses were riderless. The rest wheeled and rushed down against the

six-foot stone fence, and broke a dozen rips through it, pouring out

into the road, and scattering to any place of safety.

To make the picture complete, the

"Louisiana Tigers" stepped out of the thicket in line, and continued to

fire till the last Yankee was out of range. The rout may have started

elsewhere, but we believed that this was the beginning. We came down

from the roof and ran to the top of the hill and there beheld the entire

Yankee army in full retreat, with the Confederates plainly in view,

pursuing them. To make better speed, the Yankees abandoned wagons,

sutler stores, everything, even their guns and knapsacks. We joined in

the pursuit for a few miles, but were finally stopped by the load of

things we had picked up. Allan's first prize was a lot of candy. He soon

threw this away to load up with more oranges than he could carry. We all

made several such changes, but the most notable was Allan's. He started

home with a sword bayonet and an immense cheese about four inches thick.

He carried it on his head in the hot sun, till his head went up through

it, and then he threw it down. We could have gathered enough supplies to

have lasted us all to this day. We made many excursions and brought home

arms and ammunition to be hidden away in a secret place we had in the

house, to be for months afterwards a source of anxiety to Mother, as the

Yankees were certain to come back and search the house, as they had

already done many times. This occasion was the exit of General Banks.

\Vhen the Yankees came back the next

time, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes' Regiment camped in our apple orchard. As

soon as their tents were pitched, they seemed to move in a body to our

house, and then started a scramble for chickens, turkeys, pigs and every

living thing on the place except ourselves. This was Christmas Eve and

there were rusks in the kitchen stove for us. A Yankee soldier walked

into the kitchen, opened the stove, and started to take out the pan of

rusks. Mother was, of course, angry and desperate at being so helpless,

but she took hold of the intruder use the back of his collar, and with

the rolling pin in her right hand, ordered him to put the pan back. He

did.

Col. R. B. Hayes shortly afterward made

his headquarters in our house, which while it was galling in the extreme

to us all, was, nevertheless, a protection to us. He always behaved as a

gentleman should. He was ordered elsewhere shortly, and then we had our

home to ourselves again, but our possession was confined to the house

only. Every outbuilding and fence on the place had departed to make fire

wood, or serve some other purpose for the soldiers. One private

out-building was carried bodily to the camp and served as cook shed.

I said every living farm animal was

taken, but one cow escaped, and thereby hangs a tale. There was no

shelter left for the cow, so we had to keep her in the cellar. She was

let out at night to pick up what food she could. There being no fences,

she would wander far enough to get grass. Harry's duty was to get up

before day and find her before the Yankees hail milked her. He was some

times too late, and for the next three meals we had dry bread only, but

there came a day in that winter when dry bread was almost a luxury.

'There were some real human beings among the Yankees. The man who had

charge of the forage must have at least known that on several occasions

a bale of hay dropped off the wagon right at our cellar door. It had

hardly reached the ground before it had disappeared in the cellar.

Nobody said a word, but that meant a certain supply of milk for at least

a week or two. On one occasion, while the sergeant was sitting in the

front door of the commissary tent, Allan and I lifted the rear flap, and

softly withdrew a barrel of crackers which we hurried into our own

scanty larder. I always believed that the sergeant knew what we were

doing.

There were only two real battles around

Winchester while we were there. The second was on the occasion of the

exit of Milroy. After the Federals had occupied Winchester in

comparative security for many months, we one day noticed very anxious

looks on the faces of the Federals, and suspected that something was

about to happen. We heard of skirmishes further up the Valley, which

gradually grew nearer to Winchester and finally, one evening about dusk,

after some cannonading from the hills around the town, General 'Milroy,

pale and anxious-looking, rode through our yard up to his big fort on

the hill in the rear of our place. That night, about ten o'clock, shells

were screaming through the air, and we could see their course by the

light of the fuse. They all pointed to and from the fort. Finally, all

was quiet and everybody in our house went to bed. About four o'clock in

the morning, we were awakened by what seemed to be an earthquake. Every

window-pane in the house was broken, and we looked out of the windows,

and saw over where the fort was, a light in the heavens. As soon as

daylight came, we went to the top of the hill and found that Milroy had

blown up his magazines and departed. Milroy had been a perfect tyrant

over the people of Winchester; at least. he seemed so. He had caused our

house to be searched at least half a dozen times; had ordered Mother to

vacate it at least that many times in order that the Federals might use

it for a hospital. On each occasion, Mother would put on her bonnet,

walk into Winchester, go to General Milroy's office, and plead with him

to leave her in peace, as she had no other shelter for herself and

children. Each time, he would rip out a storm of oaths, abusing the

Confederacy, from President Davis down to the infants in the cradle, and

finally wind up by telling her she could stay. The man seemed to have

had a heart in him after all.

During one summer while we remained in

Winchester, the whole seven of us were sick with typhoid and scarlet

fever. In the midst of this came the news of brother Wood's death on the

battlefield of Gaines' Mill. I remember well how difficult it was in my

fevered delirium, to fully realize what had happened, but a sorrowing

household long afterward brought even the youngest to a full

understanding of it.

During the winter of 1862 and '63, Harry

made three or four trips to Front Royal to get money which our father

would send there for us. He had to steal through the Yankee picket

lines, both going and coming. He always succeeded but on one occasion

came near being captured. He always took with him a whip, as if he were

in search of the cow. lie found that he was about to be discovered by an

approaching squad of cavalry, and quickly crept in the hollow space left

by two Iarge logs being rolled together. He waited for the soldiers to

pass on, but instead, they not only stopped, but camped right at those

logs and built a fire against them. his suspense was long, but in a few

hours they moved on, and he crept out and came home under the protection

of the night.

On July 18th, 1863,—I remember because it

was my eleventh birth clay,—the Confederates were again about to

withdraw up the Valley of the Shenandoah, and again leave old Winchester

to the tender mercies of her enemies. Our father sent word to Mother

that she must not risk passing another winter at our old home and within

the Federal lines. She started with little else beside a spring wagon

Ioad of children, and another of household goods. Allan drove the spring

wagon containing Mother and the four smaller children. To my delight, I

was selected to ride an old lame horse. Riding on horseback such a

distance, from Winchester to Charlottesville, to me was full of

adventure, but after the first day I learned a lot about riding a horse.

I found that for an inexperienced horseman, it was next to impossible to

ride bare-backed two clays in succession in a sitting position. The

second day I rode kneeling on the horse's back, lying across her back on

my stomach, standing up on her rump—ally way but the right way, and

wound up by walking some miles.

After waiting for a few weeks at Amherst

Court House for orders, Lexington, Va., was selected as our final

stopping place, and there we arrived with little else than the clothes

we had on. The entire lot of children's clothes had been stolen on the

canal boat. We were "refugees," and they were not very welcome in

communities which had not felt the real pinch of war. While Mother was

sitting with us around her, in her room at the Lexington Hotel, where we

had established ourselves, without knowing how the bill was to be paid,

a noble woman, Mrs. McElwee, called to see us, merely from the kindness

of her good heart, and before she left she had invited Mother to bring

the children and "board" with her at her beautiful home just out of

town. Though nothing was said, both of those women knew in their hearts

that our "board" would never be paid, in all probability. It was paid,

though many years afterward, when we grew to be men.

A thing happened eight years afterward,

while I was a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute, which nearly

squared our account with the McElwees. I know that she thought so, at

any rate. One cold winter morning when the ice on the North River was

only one night old, the entire student body from Washington College and

all the V. M. I. cadets were turned loose for a day's skating. As this

scattered throng moved along the waving and snapping young ice, I

remember noticing a spot which never froze, being over a spring. The ice

got gradually thinner as it got nearer the hole. I had passed this place

only a little while, when I heard a tremendous yell and looked around to

find nearly everybody making for the shore,—anything to get away from

that dangerous hole. A closer look showed me two little red mitts—all

that could be seen—of some child struggling for its life in that bitter

cold water. I must say that I forgot all about the danger, struck out

for that hole, and when I was within about sixty feet of it, to avoid

breaking in before I got to the child, I laid flat on my face and slid

into the hole to find him gone under. I soon had him, though, and then

had plenty of time to do a little thinking. It was a desperate struggle

to keep that child's nose and mouth above the water, and with my

military overcoat and skates on, I was soon nearly worn out. I had more

than once decided that I would not let go of the child, though there was

a strong temptation to try to save myself. Every other soul had gotten

entirely off the ice, and were lined up on the bank shouting advice as

to what I should do, when I could do only the one thing, hold that child

and attempt to climb on the thin ice, to get a fresh ducking for myself

and burden every time. I had nearly given up when a tall young cadet,

who had not been one of the skaters, stepped out of the crowd with a

thin fence rail in his hands, and walked as confidently on that bending

ice as he would on a dirt road. The water came nearly up to his shoe

tops. I remember that because I was desperately afraid he would break in

before he reached me with the rail. He didn't break in, and handed me

the end of the rail and pulled me with my load up on the ice and dragged

us up where it was stronger. I then looked at the child and found that

it was Mrs. Elwees' youngest boy Will. The tall young fellow who helped

us out was Henry Murrel, of Lynchburgh.

The war operations around Lexington were

small compared with what we saw in Winchester. The only thin; of note

which occurred,—in fact the only time in which the Yankees appeared in

force—was when General Hunter came through, having shelled the town from

across the river. He burned the Virginia Military Institute, which had

given to the Confederacy so many able officers, General Stonewall

Jackson among the number; then he passed on, with hardly a stop, and on

his way, overtook our father, who had been Commander of the post at

Lexington, and captured him, carrying him to Wheeling as a prisoner.

Which story is told elsewhere.

We lived in Lexington till the war

closed. The store- of Harry's capture by the Yankees, when he was

defending his father, is also told elsewhere. After long and anxious

months of waiting, we were rewarded with his arrival home, hatless and

shoeless, with two Yankee prisoners handcuffed. After lie had made his

own escape, lie came upon these two soldiers asleep, and took away their

guns, and having a pair of handcuff's which he had picked up, he could

not resist putting them on the wrists of the two men, and marching them

into Lexington in full view of the admiring throng of boys. Although

Harry was only seventeen years old, he had the bodily strength of a

mature man. I have seen him at that age pick up a barrel of flour and

walk up the steps with it on his shoulder.

The six of us younger boys thought we

were having a hard time in those awful days just after the var. It is

painful while it lasts, but such an experience is not bad for a boy who

must make his way in the world. We learned all about making and caring

for a garden, raising four acres of potatoes a mile from home, in a

field lull of stumps. Cutting wood on shares four miles in the hills,

the owner delivering to us one-half of what we cut.

Thus the real pinch of hard times came

upon us after the war was over. Mother was at a loss to know what to do

to keep us clothed and fed. [By some means or other, Mother got hold of

a quantity of curtains, bedding, etc.. which we had left at Winchester.

They proved to be of inestimable value to us after the war, and during

the latter days of it. Nellie was dressed in all manner of things made

from the old curtains. The best clothes of the boy were made of

bed-ticking. I had a letter only a few months ago from a man in Texas,

who happened to find out where I was. He was a boy along with me in

Lexington. In his letter he said that he remembered distinctly the first

time he had over seen me. He remembered the neatness and care with which

I was dressed. In my reply to him, I said that he ought not to have any

difficulty in recalling the particular circumstance of my dress, as it

was a full suit of bed ticking.]

Gradwally things began to brighten a

little, when the two colleges at Lexington, Washington College

(afterwards Washington Lee University) and the Virginia Military

Institute, began to fill up with students. Mother saw an opportunity in

the fact that all the Washington College students had to have a place to

live, so she opened a boarding house, and for four or five years kept

things going in that way. Harry went to Washington College and Allan

went to Cool Spring, where Brother Will had a school and Brother Ed a

farm. Afterwards, Allan came to Washington College. And upon leaving

there he went to Texas. After spending a year and a half in Texas as a

school teacher, lie came to Louisville and taught with his brother

William in the Rugby School. I was placed at the Virginia Military

Institute; my brother :Marshall defraying my expenses. I graduated there

in 1873 and moved to Louisville to join Harry and Allan. The younger

boys, Nellie and Mother coming with us. Louisville has been the family

home ever since. With Harry's small experience as a civil engineer he

opened an office as an architect, and after I came from the Virginia

Military Institute (having graduated in civil engineering and what

little they taught in architecture at that school), I went in with Harry

as a partner, and with that start, the firm of McDonald Brothers,

composed of myself, Harry and Donald, was organized, which firm

practiced architecture for many years in the City of Louisville and the

surrounding country. Roy naturally fell into the building profession as

superintendent for us. He was appointed Inspector of Buildings for the

City of Louisville, but ill health overtook him, and after some years,

entirely disabled him. Donald left our firm to become Receiver for the

Kentucky Rock Gas Company. His management of this was so successful that

out of it grew the prosperous corporation now called the Kentucky

Heating Company.

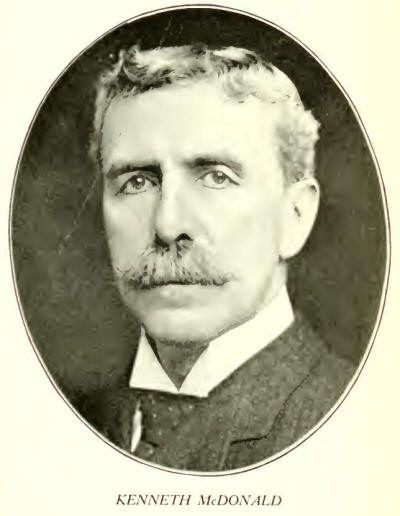

Kenneth McDonald was born in Romney,

Virginia, July 18th, 1852, being the fourth child of Angus W. McDonald

and Cornelia Peake (his wife) . After graduating at the V. M. I. he came

to Louisville with the family and soon. afterwards the firm of "McDonald

Brothers, Architects" was launched and grew into a successful business,

being responsible for many handsome buildings and artistic homes in and

around Louisville.

On November 20th, 1879, he was married to

Miss America R. Moore, of Louisville, Ky. They have three sons, Kenneth,

Allan and Graeme.

He is still a resident of Louisville and

senior member of the popular and prosperous firm of "McDonald and Dodd." |