|

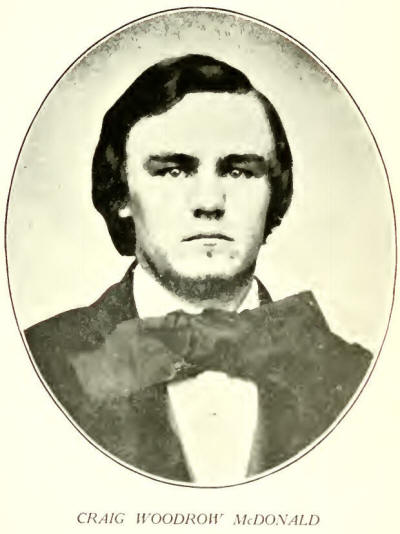

Craig Woodrow McDonald was born in Romney,

Virginia, May the 28th, 1837, the fifth son and seventh child of Angus

W. McDonald and Leacy Anne Naylor (his wife). He attended the private

schools of the town with his brothers and being very precocious he not

only kept up with his classes, but was in many instances classed with

boys who were older than himself.

He had wonderful gift of oratory even as a small boy, and I have vivid

recollection of how he would collect all the children together in an

outer room sometimes, and at others under trees in the open air, and

declaim to them Patrick Henry's famous oration, or if in romantic mood,

some stirring passages from either "Marmion" or "The Lady of the Lake."

He had a remarkably retentive memory and

could repeat pages of his favorite poems. A popular pastime with him was

capping verses, and he always led his class in declamation.

He entered the fourth class at the V. i\1.

I. at the same time that Marshall entered the third, and like his

brother, he contributed his full share to the diversions of the cadets.

Though gifted with talents of a high order, and maintaining; a good

class-standing throughout, he too, very often had more demerit to his

credit than was safe to risk. Then would come the beseeching letters to

his father, to intercede with "Old Specs," and have the dangerous

demerit cancelled, always with promises of future improvement in that

line.

Notwithstanding his frequent escapades,

Col. Smith said that he evinced talents of a very high order during his

cadetship at the Institute. A short time before he left the V. M. I.,

there was a great religious revival among the cadets and the following

letter from Wood to his sister will show the effect it had upon him

V. M. Institute,

May 31st.

DEAR SUE:

You may perhaps have heard, that I am trying to be a better boy. Yes,

dear. Sue, I am so happy to tell you that your wayward, wild, wandering

brother has, by the grace of God, at length found a home in Christ Jesus

and that I humbly hope that the prayers of my dear mother have been

answered and that God will help me to live for him and then meet her in

Heaven.

I cannot express to you how good (yes,

good in the full Methodist sense of the word) I sometimes feel when I

can in some degree realize the pleasure of the high destinies which God,

I hope, has called me to fill; high in its very lowliness, that of a

weak, stumbling follower, but thank God! still a follower of Jesus.

And, my dear Sue, little can you imagine

how much pained I feel, that some of my dear brothers and sisters will

persist in refusing to be happy. You are not happy, Sue, I know it. I

care not how gay and exhuberant your spirits are, you too, feel that

there is a hollowness in every seeming pleasure, which when thought

makes it apparent, poisons all enjoyment. And thus it is with all of us,

we go on in the pursuit of these merest shadows, disregarding the sweet

tones of the voice which His infinite mercy Sounds constantly in our

ears, to woo us back to happiness and call us home.

But I am afraid my dear sister, ,ill

think I want to lecture her. I assure her that nothing is farther from

my purpose, but I will simply ask her, in God's and then in our Mother's

name, not to disregard the warning which God has sent her in my

conversion, but to come home now. Why Sue, there is nothing in the world

to prevent it. There is no real pleasure that you will have to give up,

nothing that you will be expected to resign, and recollect what a

precious and kind Saviour you are slighting.

* * * * I hope and pray you will think

about it. Please do.

Your devoted brother, WOOD.

He entered the University of Virginia in

the Fall of 1857, at the same time that Marshall did, and two letters

which follow, written to his father, while there, give an excellent idea

of his aims and aspirations.

University of Virginia.

January 14th, 1858.

DEAR PA:

I have really been so busy in the last month, that I have not had time

to write. My examinations are very near now and it keeps me hard at work

preparing for them.

My ticket is quite a heavy one (Math.

Latin, and Modern Languages) and requires a great deal of very hard

labor. I still have every reason to hope that I will graduate on the

entire ticket, but French is so uncertain a thing however, that no man

can tell till after his examination is over, how he stands.

I had a little quarrel with Schele, too,

the early part of the session, about a remark of his in the lecture

room, and I would not be surprised, if in order to vent his spite (he is

a malicious little man), he should try to pitch me. But his decision is

not final and if I am anywhere near the standard, I think I shall

certainly appeal.

My standing on Math. and Latin is as

good, I believe, as that of any man in those classes.

Marsh has made quite a reputation here as

a man of talent. His ticket is such a large one and he does so well too,

that I don't wonder at it. He can study, or rather learn more, in a

shorter time than any man I ever saw. I suppose he will certainly

(though no man can be certain) graduate on his ticket.

Old Mr. Allen's son is a smart fellow,

and a very hard student. Archie Smith will, it is supposed, take the

degree this year.

I joined the Jefferson Society some weeks

ago, but have not spoken yet, nor do I intend to do so till after my

intermediate examinations. I hardly think I will make more than one

speech this session. I only joined because when I have the time to give

attention to it, the fact of my having been a member for sometime, will

give me position.

I was nominated for monthly orator the

night I joined (on account, I suppose, of some little reputation, as a

speaker, that I brought with me from the V. M. I.), but declined for the

reasons I have given you.

I do not desire to speak much now. I need

a vast deal more of education, both of mind and sentiment. I believe

that eloquence is the language of passion and that no man can be

eloquent unless he warmly and zealously loves what he advocates. Some

men are so gifted by nature, that they can become enamored of

abstractions and be zealous in their advocacy, but that is not the case

with myself. Unless a subject assume some tangible shape that touches me

in some vital point, I cannot arouse myself to warmth in its cause.

It is this defect which I hope to remedy

by education and I believe it can be done. I would study truth and learn

to love it, not become merely a cold admirer, but an ardent and

enlightened worshipper at her shrine, and then I know that I cannot help

but be an orator. * * * I have a plan for next year, which if it meet

with your approval, I want to carry out, that is to try and get a

situation as teacher in one of the numerous schools here. If I graduate

on my ticket, I could get, I think, a situation in some one of these

schools close enough to allow me to attend lectures.

And I believe I could command a very good

salary, at least enough to live on. Please write me immediately whether

this plan meets with your approbation, as, if I conclude to make the

effort, I shall want to make application on the spot. I don't believe it

will do me any harm to be thrown on my own resources.

Do not consent to Marsh's doing anything

of the sort, he has not got the time to spare and will, I think, be

pretty certain to take the degree in two years.

Tell them all that I intend to write as

soon as I get time. With love to all and yourself, I am, Your

affectionate son,

WOOD.

The next one was written the following

year and shows that his father evidently did not agree to his proposed

plan of taking a school:

University of Virginia.

June 5th, 1859.

DEAR PA:

Mother wrote me in her last letter that you would probably be at home by

the last of May, and I hope that this letter may reach you there.

I am very busy now, right in the midst of

my examinations. I have stood Latin and Moral Ph. and feel very

confident that I have done well and shall graduate in both. I have two

more to stand. Math, will not come off before the 21st of the month.

This is my most important examination and takes a vast deal more work to

prepare for than any other.

I submitted my Latin examination papers

to Bronaugh and Thompson directly after I came from the Hall and they

were both of the opinion that I need have no fear. Latin was

Thermopylae, and I think I am safe on my entire ticket.

Part of my object in writing this

morning, is to ask your influence with Randolph Tucker, who you are

aware is a member of the Board of Visitors, to procure his vote for

Baker Thompson, as Professor of Latin, the chair being now vacated, as

you probably know, by the resignation of Prof. Harrison. Will and I both

know him well and to both he has been a staunch friend.

I do not, of course, urge this as one of

his qualifications for office, but only to enlist your kindly feeling

towards him. He is certainly, in my judgment, one of the ablest men in

the State (of whom I know anything) of his age; his scholarship, both

for profundity and accuracy is irreproachable. Will you not write to Mr.

Tucker in his favor?

I remember now that you have some

acquaintance with him yourself and can testify to his ability. There is

another way in which you might advance his interests, and that is by

speaking to Senator Mason, who can have a good deal of influence over

Muscoe Garnett, who is a member of the board. The election will take

place on the 25th of June and if you decide to do anything for him it

should be done quickly. I have had a strong idea of writing to Mr.

Tucker myself, but thought it might look like officiousness, and

preferred to write to you.

The time is fast approaching when the

session will be over and I will be at home. I am very glad it is so

near, though, I confess that ,lust now I should like to have the power

of commanding the sun and moon to stand still, until I had finished

preparing for Math.

I shall need, in order to pay my debts,

and bring me home, $200 dollars. This will make the amount spent this

year, traveling expenses from Winchester here included, $510.00 and when

you remember that my matriculation fees, as sent you in Proctor's

receipt, were $145.00 and that I paid $25.00 additional for another

ticket, making in all for matriculation fees $170.00, you will not think

me extravagant.

I would like to have the money as soon as

you can conveniently send it, for I think it highly probable that I

shall come home as soon as I stand all my examinations, as all lectures

will be suspended by that time, and there will be nothing going on here

except stupid celebrations, dinners, etc., of which I got my fill last

year.

I hope Will will be at home soon. An old

friend of his—Joseph Anderson—will be married on the 30th, and seems

very anxious that Will should be here. I expect, however, that they have

been in correspondence before this. If Will comes, of course I shall

stay until he goes home. My love to all at home.

Your affectionate son,

C. W. MCDONALD

After leaving the University of Virginia,

he taught in the family of Mr. James Beckham, of Culpeper County,

Virginia, and was teaching there at the beginning of the war, and at the

same time studying law with his brother-in-law, Mr. Jas. W. Green,

riding to the court house every week to stand his examinations. He

promptly resigned his position and enlisted in the Brandy Rifles—a

volunteer company of the county—at the first call to arms, and

participated in the capture of Harper's Ferry.

Soon after that, he was commissioned as

Lieutenant in the P. A. C. and assigned to duty on General Elzey's

staff, and in all the contests in which he participated—in the

Shenandoah Valley, as well as on the historic plains of Manasses—he won

the highest enconiums of praise from his commanding officers. After the

battle of Cross Keys, he performed a most hazardous and dangerous

service in firing the bridge at Port Republic, for which daring act, he

was promoted to a Captaincy.

A very short time before he was killed he

came to Lynchburg on a short furlough to replenish his wardrobe and to

visit his sisters, who were there as refugees. All of them had noticed a

marked change from his usually buoyant, gay manner, to a more sedate and

serious frame of mind, and one of them, in a teasing spirit, twitted him

about it, he replied that the life of a soldier was calculated to make

one either altogether reckless or very thoughtful, and he was glad that

he inclined to the serious side. The early teachings of a Christian

mother seemed ever present with him and had a marked influence in the

formation of his character.

Just before he was to start back to his

command we were all together discussing the all-absorbing topic of the

time, when Wood proposed that we should sing a hymn which had always

been a favorite with him, "My Days are Gliding Swiftly by," which, in

the light of the sad event following so closely upon the visit, seemed

almost a promonition, for it was only a few short days before he was

killed at the battle of Gaines' Mills.

During the progress of this battle, he

was sent with an order to the 13th Va. Infantry, instructing them to

occupy a certain position in the line of battle. The officer in command

of the regiment said he could not understand from the order, just where

he was expected to go, and Wood volunteered to lead the regiment to the

point himself, which was exposed to a raking fire from both infantry and

artillery. Before reaching the position, however, he had his horse shot

under him and he was obliged to secure another, and had advanced but a

short distance, when he received a fatal wound in the breast with grape

shot, killing him instantly.

In the heat and confusion of the

engagement, which ensued, his body lay where it fell, until found later

by his brother-in-law, Judge Thomas C. Green, then a private in the

Botts Grays, 2nd reg. Stonewall Brigade. A scrap of paper was found

pinned to his breast bearing the following inscription:

"Lieut. C. W. McDonald, Aid on General

Elzey's staff. Killed in the battle of the 29th of May, 1862. A noble

man and a brave soldier. He died valiantly fighting for his country."

(Original paper in possession of Mrs. J.

B. Stan-and, his sister Sue.)

He was buried in Holliwood Cemetery,

Richmond, Virginia, in the lot belonging to Mr. William Sherard, but

since the war removed to a section occupied exclusively by Confederate

soldiers.

"Fame's eternal camping

ground."

In the brief sketch I have given of the

life of "Wood McDonald" which was brought to such a sad and untimely

end, I have had very little data to rely on, and felt that a better idea

might be gained of his personality from some of his own letters than

from anything I might say. These letters have not been selected,

however, from among many others, but are the only ones I could find that

had escaped the ravages of the war, and one might gather from their

tenor that he was of a much more serious turn of mind and disposition

than he was in reality.

He was richly dowered by nature in both

person and mind and added to that was a most magnetic and engaging

manner and these attractions, together with a rich melodious voice in

singing, made him very much sought after in society. |