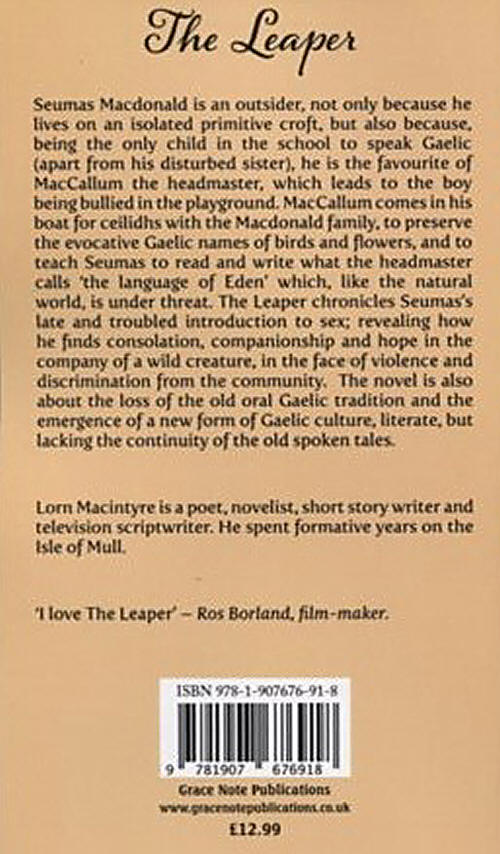

Lorn Macintyre was

born in Taynuilt, Argyll, and spent formative years on the Isle of Mull, both

places being the inspiration for his poetry and prose and his exposure to Gaelic

culture. His doctorate on Sir Walter Scott and the Highlands shows how that area

of Scotland was romanticised and misrepresented in literature by ‘the Wizard of

the North,’ with lasting detriment. Lorn is the author of the Chronicles

of Invernevis,

about a Highland landed family, of which four in the series of novels have been

published. He has published two acclaimed collections of short stories based on

his years on Mull and its characters, including his own legendary father Angus,

poet, bank manager and obsessed Gael. His poetry, like his fiction, records and

laments the disappearance of a traditional way of life, with accompanying

decline in the Gaelic language, and the exploitation of the environment, with

some wildlife under threat of extinction through the use of chemicals. Lorn’s

website is at:

http://www.lornmacintyre.co.uk/

First Four Pages of Chapter 1

One

‘Buntŗta’s sgadan.’

The old man had requested potatoes and herring for supper as if the Gaelic feast

were already in his mouth that May day in 1983. Seumas had dug up the big

potatoes he had planted, washing them under the tap in the chipped stone sink in

the scullery. He filled a pot from the sea to cook the herring he had been given

off a boat in the town because you couldn't catch them any more with feathered

hooks off Rubha nan Ron. While supper was cooking on the open flames of the

range he spread the local paper out on the table, then carried the two pots

through to the scullery to drain them, returning to tumble out their contents

into two heaps on the paper before helping the old man to the table.

After his stroke the old man's right arm was like a useless flipper across his

chest. Once the most sure-footed of men, especially in a pitching boat, he now

lurched to the table as if he had a cargo of whisky in him. They sat opposite

each other, using only their hands. The old man picked up a potato, imprinted

with ink from the death notices, breaking it in his fingers and when the steam

had escaped he put a piece into his mouth before peeling the silver skin from

the fish and breaking off a portion.

'Tha seo blasta,' this is tasty, he pronounced.

The old man was wearing an open shirt and trousers with braces, sagging at the

waist, like a clown's outfit, completed by his bulbous red nose. He had

sandshoes without laces on his feet for the comfort of his corns. He wasn't tall

but he had wide shoulders and had been a ferocious fighter in his time, on one

memorable occasion, stripped to the waist in a blizzard, taking on two big men

off a Fleetwood trawler and thrashing them. As his son fondly watched him eating

he smiled at the thought that the old man looked like a seal, with his bald

head, his whiskers, and no neck on the powerful physique. He was eating potatoes

and herring, representing the two toils of his life, the earth and the sea.

There was a little pile of fish skins by his left hand, but he ate the potato

skins, with the dark soil in their crevices. He was laying the fish bones at the

edge of the paper as if engaged in creating an intricate puzzle.

'Tha mi dol don taigh-bheag,' I'm going to the little house, the old man

announced suddenly, hobbling towards the door.

Dileas, faithful, the collie dog, came back alone ten minutes later, whining and

pawing Seumas's foot. He ran round the corner of the house. The old man had

fallen asleep in the stifling taigh-beag, on the plank with the hole in it, his

head on his chest, trousers round his sandshoes, a bluebottle sounding

mournfully in the enamel pail under him.

'Tiugainn,' come along, the son coaxed gently, catching the old man's hand.

The old man pitched forward, his face among the buidheagan an t-samhraidh, the

buttercup, little yellow one of the summer, on the bank of Allt a' Ghobha-Uisge,

the burn of the water ouzel, as it swung behind the house on its way down to the

bay. Seumas knelt, turning the old man over and opening his shirt before putting

his mouth to the old man's white moustache and trying to pump life back into his

chest. Seventy three years of the scent of peat fires were ingrained in his

skin. But the old man was getting cold, and his eyes had rolled up into his head

as if to show that he was finished with the world. The doctor would have to walk

over the hill to tell the son something he already knew, that his athair had

gone, and the undertaker would have to come to measure him, then take the coffin

over the moor on a hired tractor. He couldn't afford it.

He wiped the old man's tÚn

with torn-up newspaper from the rusty nail in the taigh-beag and

carried him on his back, grasping him by the wrists, the sandshoes slithering

through the grass in which the ticking of the grasshopper sounded like a lost

watch. He removed the old man's clothes and sat him naked on the plain wooden

chair in front of the fire, holding him in place with a length of rope wound

round his chest and secured to the chair back. He used the hot water in the

kettle to wash the old man tenderly, as though he were an infant, taking a wet

cloth to the moustache to get the pieces of his last feast of herring out of it.

He thought about shaving him, but it would be difficult, the way his head kept

slumping forward.

Seumas went upstairs and brought down the only suit the old man had possessed

and the white shirt last worn for his wife's funeral, but leaving off the black

tie. He dressed the old man, putting the sandshoes back on his bare feet. He

pulled in the dinghy on the rope and waded out to it with the old man on his

back. He had to take the dog on this final journey because she had been the old

man's and because she adored her dead master, which was why Dileas, whom the old

man claimed understood Gaelic like a human, was whimpering and licking the old

man's ankles.

He transferred the corpse to the launch and laid out the old man between the

seats with one of his creels as a pillow. The old man whose name was Murchadh,

Murdo, had made the creel on the shore in a long-ago summer, bending the steamed

hazel wands over the flat stone for ballast on the board, then plying the big

wooden needle to make the lattice pattern with the twine before brushing on the

pungent pitch from the pot.

Seumas lifted the cover off the engine and jerked the cord, standing at the

tiller as he headed across the bay, round Rubha nan Ron, the Promontory of the

Seals, where the old man had always shot his creels because he said that an iron

ship had gone down there in his grandfather's time and that the holds gave the

lobsters shelter to grow big. The old man and he had worked side by side pulling

up the slimed ropes, talking in Gaelic about other things because it was a

rarity then for a creel not to contain a lobster. Seumas had seen two lobsters

in the one creel, their claws so tangled in combat that the old man couldn't

separate them and had to sacrifice the smaller one.

But the lobsters were small now, and some had dark mottling on their shells

which the buyer wouldn't touch because he said that the top people in the London

restaurants wouldn't pay for blemishes on shellfish delivered whole to their

tables.

The launch with his father's corpse stiffening across the seats, his moustache

dripping with spray, the dog lying beside her master as if her body heat could

bring him back to life, passed the fish farm on the port side, Sgeir nan Eun,

the Skerry of the Birds, to starboard. The town (though it hardly merited the

status, because there were only six hundred inhabitants) was two miles round the

treacherous coast and when the launch puttered to the steps beside the pier he

left the body in it and went into the telephone box, but there was no book to

give him the doctor's number, so he had to phone directory enquiries. The

doctor's receptionist said that he was out on a call.

'Can I take a message?'

'It's Seumas Macdonald here. My father's just died and I brought him round in

the boat.'

The receptionist asked him to repeat what he had just said.

'He's lying in your boat at the pier?' she reiterated incredulously.

'Yes. I brought him round because there's no road to the house for the

undertaker.'

'I think you should phone the police,' the receptionist advised.

'I haven't murdered him.'

Books can be purchased at:

www.gracenotepublications.co.uk and also on Amazon.