|

Mr Skene says of the clan Grant, "Nothing

certain is known regarding the origin of the Grant. They have been said to be of Danish,

English, French, Norman, and of Gaelic extraction; but each of these suppositions depends

for support upon conjecture alone, and amidst so many conflicting opinions it is

difficult to fix upon the most probable. It is maintained by the supporters of their

Gaelic origin, that they are a branch of the Macgregors, and in this opinion they are

certainly borne out by the ancient and unvarying tradition of the country; for their

Norman origin, I have upon examination entirely failed in discovering any further reason

than that their name may be derived from the French, grand or great, and that they occasionally use the Norman form of de Grant. The latter reason, however, is not of any

force, for it is impossible to trace an instance of their using the form de Grant until

the 15th century; on the contrary, the form invariably Grant or le Grant, and on the very

first appearance of the family it is 'dictus Grant'. It is certainly not a territorial

name, for there was no ancient property of that name, and the peculiar form under which it

invariably appears in the earlier generations, proves that the name is derived from a

personal epithet. It so happens, however, that there was no epithet so common among the

Gael as that of Grant, as a perusal of the Irish annals will evince; and at the same time

Ragman's Roll shows that the Highland epithets always appear among the Normal signatures

with the Norman 'le' prefixed to them. The clan themselves unanimously assert their

descent from Gregor Mor Macgregor, who lived in the 12th century; and this is supported by

their using to this day the same badge of distinction. So strong is this belief in both

the clans of Grant and Macgregor, that in the early part of the last century a meeting of

the two was held in the Blair of Athole, to consider the policy of re-uniting them. Upon

this point all agreed, and also that the common surname should be Macgregor, if the

reversal of the attainder of that name could be got from the government. If that could not

be obtained it was agreed that either MacAlpine or Grant should be substituted. This

assembly of the clan Alpine lasted for fourteen days, and was only rendered abortive by

disputes as to the chieftainship of the combined clan. Here then is as strong an

attestation of a tradition as it is possible to conceive, and when to this is added the

utter absence of the name in the old Norman rolls, the only trustworthy mark of a Norman

descent, we are warranted in placing the Grants among the Siol Alpine".

With Mr Smibert we are inclined to think that, come the clan designation whence it may,

the great body of the Grants were Gael of the stock of Alpine, which, as he truly says, is

after all the main point to be considered.

The first of the name on record in Scotland is Gregory de Grant, who, in the reign of

Alexander II (1214-1249), was sheriff of the shire of Inverness, which then, and till

1583, comprehended Ross, Sutherland, and Caithness, besides what is now Inverness-shire.

By his marriage with Mary, daughter of Sir John Bisset of Lovat, he became possessed of

the lands of Stratherrick, at that period a part of the province of Moray, and had two

sons, namely, Sir Lawrence, his heir, and Robert, who appears to have succeeded his father

as sheriff of Inverness.

The elder son, Sir Lawrence de Grant, with his brother Robert, witnessed an agreement,

dated 9th Sept, 1258, between Archibald, bishop of Moray, and John Bisset of Lovat; Sir

Lawrence is particularly mentioned as the friend and kinsman of the latter. Chalmers

states that he married Bigla, the heiress of Comyn of Glenchernach, and obtained his

father-in-law's estates in Strathspey, and a connection with the post potent family in

Scotland. Douglas, however, in his Baronage, says that she was the wife of his elder son,

John. He had two sons, Sir John and Rudolph. They supported the interest of Bruce against

Baliol, and were taken prisoners in 1296, at the battle of Dunbar. After Baliol's

surrender of his crown and kingdom to Edward, the English monarch, with his victorious

army, marched north as far as Elgin. On his return to Berwick he received the submission

of many of the Scottish barons, whose names were written upon four large rolls of

parchment, so frequently referred to as the Ragmans Roll. Most of them were dismissed on

their swearing allegiance to him, among whom was Rudolph de Grant, but his brother, John

de Grant, was carried to London. He was released the following year, on condition of

serving King Edward in France, John Comyn of Badenoch being his surety on the occasion.

Robert de Grant, who also swore fealty to Edward I in 1296, is supposed to have been his

uncle.

At the accession of Robert the Bruce in 1306, the Grants do not seem to have been very

numerous in Scotland; but as the people of Strathspey, which from that period was knows as

"the country of the Grants", came to form a clan, with their name, they soon

acquired the position and power of Highland chiefs.

Sir John had three sons - Sir John, who succeeded him; Sir Allan, progenitor of the clan

Allan, a tribe of the Grants, of whom the Grants of Auchernick are the head; and Thomas,

ancestor of some families of the name. Sir John's grandson, John de Grant, had a son; and

a daughter, Agnes, married to Sir Richard Comyn, ancestor of the Cummings of Altyre. The

son, Sir Robert de Grant, in 1385, when the king of France, then at war with Richard II,

remitted to Scotland a subsidy of 40,000 French crowns, to induce the Scots to invade

England, was one of the principal barons, about twenty in all, among whom the money was

divided. He died in the succeeding reign.

At this point there is some confusion in the pedigree of the Grants. The family papers

state that the male line was continued by the son of Sir Robert, named Malcolm, who soon

after his father's death began to make a figure as chief of the clan. On the other hand,

some writers maintain that Sir Robert had no son, but a daughter, Maud or Matilda, heiress

of the estate, and lineal representative of the family of Grant, who about the year 1400

married Andrew Stewart, son of Sir John Stewart, commonly called the Black Stewart,

sheriff of Bute, and son of King Robert II, and that this Andrew sunk the royal name, and

assumed instead the name and arms of Grant. This marriage, however, though supported by

the tradition of the country, is not acknowledged by the family or the clan, and the very

existence of such an heiress is denied.

Malcolm de Grant, above mentioned, had a son, Duncan de Grant, the first designed of

Freuchie, the family title for several generations. By his wife, Muriel, a daughter of

Mackintosh of Mackintosh, captain of the clan Chattan, he had, with a daughter, two sons,

John and Patrick. The latter, by his elder son, John, was ancestor of the Grants of

Ballindalloch, county of Elgin, of whom afterwards, and of those of Tomnavoulem, Tulloch,

&c; and by his younger son, Patrick, of the Grants of Dunlugas in Banffshire.

Duncan's eldest son, John Grant of Freuchie, by his wife, Margaret, daughter of Sir James

Ogilvie of Deskford, ancestor of the Earls of Findlater, had, with a daughter, married to

her cousin, Hector, son of the chief of Mackintosh, three sons - John, his heir; Peter of

Patrick, said to be the ancestor of the tribe of Phadrig, or house of Tullochgorum; and

Duncan, progenitor of the tribe called clan Donachie, or house of Gartenbeg. By the

daughter of Baron Stewart of Kincardine, he had another son, also named John, ancestor of

the Grants of Glenmoriston.

His eldest son, John, the tenth laird, called, from his poetical talents, the Bard,

succeeded in 1508. He obtained four charters under the great seal, all dated 3d December

1509, of various lands, among which were Urquhart and Glenmoriston in Inverness-shire. He

had three sons; John, the second son, was ancestor of the Grants of Shogglie, and of those

of Corrimony in Urquhart.

The younger son, Patrick, was the progenitor of the Grants of Bonhard in Perthshire. John

the Bard died in 1525.

His eldest son, James Grant of Freuchie, called, from his daring character, Shemas nan

Creach, of James the Bold, was much employed, during the reign of King James V, in

quelling insurrections in the northern counties. His lands in Urquhart were, in November

1513, plundered and laid waste by the adherents of the Lord of the Isles, and again in

1544 by the Clanranald, when his castle of Urquhart was taken possession of. This chief of

the Grants was in such high favour with King James V that he obtained from that monarch a

charter, dated 1535, exempting him from the jurisdiction of all courts of judicature,

except the court of session, then newly instituted. He died in 1553. He had with two

daughters, two sons, John and Archibald; the latter the ancestor of the Grants of Cullen,

Monymusk, &c.

His eldest son, John, usually called Evan Baold, or the Gentle, was a strenuous promoter

of the Reformation, and was a member of that parliament which, in 1560, abolished Popery

as the established religion of Scotland. He died in 1585, having been twice married -

first, to Margaret Stewart, daughter of the Earl of Athole, by whom he had, with two

daughters, two sons, Duncan and Patrick, the latter ancestor of the Grants of

Rothiemurchus; and, secondly, to a daughter of Barclay of Towie, by whom he had an only

son, Archibald, ancestor of the Grants of Bellintomb, represented by the Grants of

Monymusk.

Duncan, the elder son, predeceased his father in 1581, leaving four sons - John; Patrick,

ancestor of the Grants of Easter Elchies, of which family was Patrick Grant, Lord Elchies,

a lord of session; Robert, progenitor of the Grants of Lurg; and James, of Ardnellie,

ancestor of those of Moyness.

John, the eldest son, succeeded his grandfather in 1585, and was much employed in public

affairs. a large body of his clan, at the battle of Glenlivet, was commanded by John Grant

of Gartenbeg, to whose treachery, in having, in terms of as concerted plan, retreated with

his men as soon as the action began, as well as to that of Campbell of Lochnell, Argyll

owed his defeat in that engagement. This laird of Grant greatly extended and improved his

paternal estates, and is said to have been offered by James VI, in 1610, a patent of

honour, which he declined. From the Shaws he purchased the lands of Rothiemurchus, which

he exchanged with his uncle Patrick for the lands of Muchrach. On his marriage with Lilias

Murray, daughter of John, Earl of Athole, the nuptials were honoured with the

presence of

King James VI and his queen. Besides a son and daughter by his wife, he had a natural son,

Duncan, progenitor of the Grants of Cluney. He died in 1622.

His son, Sir John, by his extravagance and attendance at court, greatly reduced his

estates, and when he was knighted he got the name of "Sir John Sell-the-land".

he had eight sons and three daughters, and dying at Edinburgh in April 1637, was buried at

the abbey church of Holyroodhouse.

His elder son, James, joined the Covenanters on the north side of the Spey in 1638, and on

19th July 1644, was, by the Estates, appointed one of the committee for trying the

malignants in the north. after the battle of Inverlochy, however, in the following year,

he joined the standard of the Maquis of Montrose, then in arms for the king, and ever

after remained faithful to the royal cause. In 1663, he went to Edinburgh, to see justice

done to his kinsman, Allan Granr of Tulloch, in a criminal prosecution for manslaughter,

in which he was successful; but he died in that city soon after his arrival there. A

patent had been made out creating him Earl of Strathspey, and Lord Grant of Freuchie and

Urquhart, but in consequence of his death it did not pass the seals. The patent itself is

said to be preserved in the family archives. He had two sons, Ludovick and Patrick, the

latter ancestor of the family of Wester Elchies in Speyside.

Ludovick, the eldest son, being a minor, was placed under the guardianship of his uncle,

Colonet Patrick Grant, who faithfully discharged his trust, an so was enabled to remove

some of the burdens on the encumbered family estates. Ludovick Grant of Grant and Freuchie

took for his wife Janet, only child of Alexander Brodie of Lethen. By the favour of his

father-in-law, the laird of Grant was enabled in 1685, to purchase the barony of

Pluscardine, which was always to descend to the second son. By King William he was

appointed colonel of a regiment of foot, and sheriff of Inverness. In 1700 he raised a

regiment of his own clan, being the only commoner that did so, and kept his regiment in

pay a whole year at his own expense. In compensation, three of his sons got commissions in

the army, and his lands were erected into a baroncy. He died at Edinburgh in 1718, in his

66th year, and, like his father and grandfather, was buried in Holyrood abbey.

Alexander, his eldest son, after studying the civil law on the continent, entered the

army, and soon obtained the command of a regiment of foot, with the rank of brigadier.

When the rebellion broke out, being with his regiment in the south, he wrote to his

brother, Captain George Grant, to raise the clan for the service of government, which he

did, and a portion of them assisted at the reduction of Inverness. as justiciary of the

counties of Inverness, Moray and Banff, he was successful in suppressing the bands of

outlaws and robbers which infested these counties in that unsettled time. He succeeded his

father in 1718, but died at Leith the following year, aged 40. Though twice married, he

had no children.

His brother, Sir James Grant of Pluscardine, was the next laird. In 1702, in his father's

lifetime, he married Anne, only daughter of Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss, Baronet. By

the marriage contract it was specially provided that he should assume the surname and arms

of Colquhoun, and if he should at any time succeed to the estate of Grant, his second son

should, with the name of Colquhoun, become proprietor of Luss. In 1704, Sir Humphrey

obtained a new patent in favour of his son-in-law, James Grant, who on his death, in 1715,

became in consequence Sir James Grant Colquhoun of Luss, Baronet. On succeeding, however,

to the estate of Grant four years after, he dropped the name of Colquhoun, retaining the

baronetcy, and the estate of Luss went to his second surviving son. He had five daughters,

and as many sons, viz Humphrey, who predeceased him in 1732; Ludovick; James, a major in

the army, who succeeded to the estate and baronetcy of Luss, and took the name of

Colquhoun; Francis, who died a general in the army; and Charles, a captain in the Royal

Navy.

The second son, Ludovick, was admitted advocate in 1728; but on the death of his brother

he relinquished his practice at the bar, and his father devolving on him the

management of

the estate, he represented him thereafter as chief of the clan. He was twice married -

first, to a daughter of Sir Robert Dalrymple of North Berwick, by whom he had a

daughter, who died young; secondly, to Lady Margaret Ogilvie, eldest daughter of James Earl

of Findlater and Seafield, in virtue of which marriage his grandson succeeded to the

earldom of Seafield. By his second wife Sir Ludovick had one son, James, and eleven

daughters, six of whom survived him. Penuel, the third of these, was the wife of Hentry

Mackenzie, Esq, author of Man of Feeling. Sir Ludovick died at Castle Grant, 18th March

1773.

His only son, Sir James Grant of Grant, baronet, born in 1738, was distinguished for his

patriotism and public spirit. On the declaration of was by France in 1793, he was among

the first to raise a regiment of fencibles, called the Grant or Strathspey fencibles, of

which he was appointed colonel. after a lingering illness, he died at Castle Grant on 18th

February 1811. He had married in 1763, Jean, only child of Alexander Duff, Esq, of Hatton,

Aberdeenshire, and had by her three sons and three daughters. Sir Lewis Alexander Grant,

the eldest son, in 1811 succeeded to the estates and earldom of Seafield, on the

death of

his cousin, James Earl of Findlater and Seafield, and his brother, Francis William,

became, in 1840, sixth earl. The younger children obtained in 1822 the rank and precedency

of an earl's junior issue.

The Grants of Ballindalloch, in the parish of Inveravon, Banffshire - commonly called the

Criag-Achrochean Grants - as already stated, descend from Patrick, twin brother of John,

ninth laird of Freuchie. Patrick's grandson, John Grant, was killed by his kinsman, John

Roy Grant of Carron, as afterwards mentioned, and his son, also John Grant, was father of

another Patrick, whose son, John Roy Grant, by his extravagant living and unhappy

differences with his lady, a daughter of Leslie of Balquhain, entirely ruined his estate,

and was obliged to consent to placing it under the management and trust of three of his

kinsmen, Brigadier Grant, Captain Grant of Elchies, and Walter Grant of Arndilly, which

gave occasion to W. Elchies' verses of "What meant the man?".

General James Grant of Ballindalloch succeeded to the estates on the death of his nephew,

Major William Grant, in 1770. He died at Ballindalloch, on 13th April 1806, at the age of

86. Having no children, he was succeeded by his maternal grand-nephew, George Macpherson,

Esq of Invereshie, who assumed in consequence the additional name of Grant, and was

created a baronet in 1838.

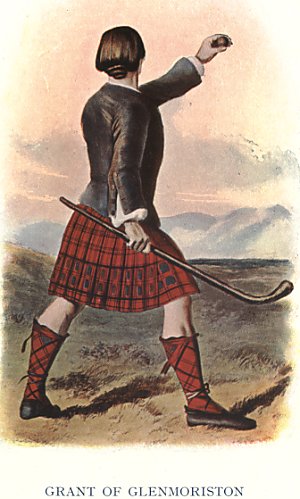

The Grants of Glenmoriston, in Inverness-shire, are sprung from John More Grant, natural

son of John Grant, ninth laird of Freuchie. His son, John Roy Grant, acquired the lands of

Carron from the Marquis of Huntly. In a dispute about the marches of their respective

properties, he killed his kinsman, John Grant of Ballindalloch, in 1588, an event which

led to a lasting feud between the families. John Roy Grant had four sons - Patrick, who

succeeded him in Carron; Robert of Nether Glen of Rothes; James an Tuim, or James of the

hill; and Thomas.

The Glenmoriston branch of the Grants adhered faithfully to the Stuarts. Patrick Grant of

Glenmoriston appeared in arms in Vicount Dundee's army at Killiecrankie. He was also at

the skirmish at Cromdale against the government soon after, and at the battle of Sheiffmuir

in 1715. His estate was, in consequence, forfeited, but through the interposition of the

chief of the Grants, was brought back from the barons of the Exchequer. The laird of

Glenmoriston in 1745 also took arms for the Pretender; but means were found to preserve

the estate to the family. The families proceeding from this branch, besides that of

Carron, which estate is near Elchies, on the river Spey, are those of Lynachoarn,

Aviemore, Croskie, &C.

The favourite song of "Roy's Wife of Aldivalloch" (the only one she was ever

known to compose), was written by a Mrs Grant of Carron, whose maiden name was Grant,

born, near Aberlour, about 1745. Mr Grant of Carron, whose wife she became about 1763, was

her cousin. After his death she married, a second time, an Irish physician practising at

Bath, of the name of Murray, and died in that city in 1814.

The Grants of Dalvey, who possess a baronetcy, are descended from Duncan, second son of

John the Bard, tenth laird of Grant.

The grants of Monymusk, who also possess a baronetcy (date of creation, December 7, 1705),

are descended from Archibald Grant of Ballintomb, an estate conferred on him by charter,

dated 8th March 1580. He was called Evan Baold, or the Gentle, by his second wife, Isobel

Barclay. With three daughters, Archibald Grant had two sons. The youngest son, James, was

designed of Tombreak. Duncan of Ballintomb, the elder, had three sons - Archibald, his

heir; Alexander, of Allachie; and William, of Arndillie. The eldest son, Archibald, had,

with two daughters, two sons, the elder of whom, Archibald grant, Esq of Bellinton, had a

son, Sir Francis, a lord of session, under the title of Lord Cullen, the first baronet of

this family.

The Grants of Kilgraston, in Perthshire, are lineally descended, through the line of the

Grants of Glenlochy, from the ninth laird of Grant. Peter Grant, the last of the lairds of

Glenlochy, which estate he sold, had two sons, John and Francis. The elder son, John,

chief justice of Jamaica from 1783 to 1790, purchased the estates of Kilgraston and

Pitcaithley, lying contiguous to each other in Strathearn; and dying in 1793, without

issue, he was succeeded by his brother, Francis. This gentleman married Anne, eldest

daughter of Robert Oliphant, Esq of Rossie, postmaster-general of Scotland, and had five

sons and two daughters. He died in 1819, and was succeeded by his son, John Grant, the

present representative of the Kilgraston family. He married - first, 1820, Margaret,

second daughter of the late Lord Gray; second, 1828, Lucy, third daughter of Thomas, late

Earl of Elgin. Heir, his son, Charles Thomas Constantine, born, 1831, and married, 1856,

Matilda, fifth daughter of William Hay, Esq, of Dunse Castle.

The badge of the clan Grant was the pine or cranberry heath, and their slogan or gathering

cry, "Stand fast, Craigellachie!" the bold projecting rock of that name

("the rocj of alarm") in the united parishes of Duthil and Rothiemurchus, being

their hill of rendezvous. The Grants had a long-standing feud with the Gordons, and even

among the different branches of themselves there were faction fights, as between the

Ballindalloch and Carron Grants. The clan, with few exceptions, was noted for its loyalty,

being generally, and the family of the chief invariably, found on the side of government.

In Strathspey the name prevailed almost to the exclusion of every other, and to this day

Grant is the predominant surname in the district, as alluded to by Sir Alexander Boswell,

Baronet, in his lively verses:-

"Come the Grants of Tullochgorum,

Wi' their pipes gaun before 'em,

Proud the mothers are that bore 'em.

Next the Grants of Rothiemurchus,

Every man his sword and durk has,

Every man as proud's a Turk is".

In 1715, the force of the clan was 800, and in 1745, 850.

Another Account of the Clan

BADGE: Giuthas (pinus

sylvestris) pine.

SLOGAN: Stand fast, Craig Elachaidh.

PIBROCH: Craigelachaidh.

THERE

seems no good reason to

doubt that Clan Grant was originally of the same ancient royal stock as

Clan Gregor. It is true that there is a family of the same name in

England, but it is of a separate and different origin, and probably

derived its patronymic from the ancient name of the river Cam, which was

originally the Granta, or from the ancient designation of Cambridge, which

was the Caer Grant of the early Saxons. Early in the eighteenth century,

when there seemed some prospect of the proscription of the name MacGregor

being removed, a meeting of the MacGregors and the Grants was held in

Blair Athol, and it was proposed that, in view of their ancient

relationship, the two clans should adopt a common name and acknowledge a

single chief. The meeting lasted for fourteen days, and, though it finally

broke up without coming to an agreement, several of the Grants, like the

Laird of Ballindalloch, showed their loyalty to the ancient kinship by

adding the MacGregor patronymic to their name. According to the tradition

of the clan, the founder of the Grants was Gregor, second son of Malcolm,

chief of the MacGregors in the year 1160. It is said he took his

distinguishing cognomen from the Gaelic Grannda, or

"ugly," in allusion to the character of his features. It is

possible, however, that this branch of Clan Alpin took its name rather

from the country in which it settled. In the district of Strathspey is a

wide moor known as the "griantach," or Plain of the Sun, the

number of pagan remains scattered over its surface showing it to

have been in early times a chief centre of the Beltane or Sun Worship.

Residents here would be set down by the early monkish writers under the

designation of "de

Griantach" or "de

Grant." This latter suggested origin of the name is supported by the

crest of the Grant family, which is a Mountain in Flames, an obvious

allusion to the Baal-teine or Baal-fire of the early pagan faith. THERE

seems no good reason to

doubt that Clan Grant was originally of the same ancient royal stock as

Clan Gregor. It is true that there is a family of the same name in

England, but it is of a separate and different origin, and probably

derived its patronymic from the ancient name of the river Cam, which was

originally the Granta, or from the ancient designation of Cambridge, which

was the Caer Grant of the early Saxons. Early in the eighteenth century,

when there seemed some prospect of the proscription of the name MacGregor

being removed, a meeting of the MacGregors and the Grants was held in

Blair Athol, and it was proposed that, in view of their ancient

relationship, the two clans should adopt a common name and acknowledge a

single chief. The meeting lasted for fourteen days, and, though it finally

broke up without coming to an agreement, several of the Grants, like the

Laird of Ballindalloch, showed their loyalty to the ancient kinship by

adding the MacGregor patronymic to their name. According to the tradition

of the clan, the founder of the Grants was Gregor, second son of Malcolm,

chief of the MacGregors in the year 1160. It is said he took his

distinguishing cognomen from the Gaelic Grannda, or

"ugly," in allusion to the character of his features. It is

possible, however, that this branch of Clan Alpin took its name rather

from the country in which it settled. In the district of Strathspey is a

wide moor known as the "griantach," or Plain of the Sun, the

number of pagan remains scattered over its surface showing it to

have been in early times a chief centre of the Beltane or Sun Worship.

Residents here would be set down by the early monkish writers under the

designation of "de

Griantach" or "de

Grant." This latter suggested origin of the name is supported by the

crest of the Grant family, which is a Mountain in Flames, an obvious

allusion to the Baal-teine or Baal-fire of the early pagan faith.

The first of the name to

appear in written records was Gregor, Sheriff of Inverness in the reign of

Alexander II., between 1214 and 1249. It was probably this Gregor de Grant

who obtained Stratherick through marriage with an heiress of the Bisset of

Lovat and Aboyne. The son of this magnate, by name Laurence or Laurin, who

was witness to a deed by the Bishop of Moray in 1258, obtained wide lands

in Strathspey by marrying the heiress of Gilbert Comyn of Glencharny; and

the son of Laurin, Sir Ian, was a noted supporter of the patriot Wallace.

It may have been about this

time that the incident happened which transferred the stronghold, now

known as Castle Grant in Strathspey, from the ownership of the once

powerful Comyns to that of the Grants. According to tradition a younger

son of Grant of Stratherick ran away with and married the daughter of his

host, the Chief of MacGregor. With thirty followers the young couple fled

to Strathspey and took refuge in the fastness now known as Huntly’s

Cave, a little more than a mile from the castle, at that time known as

Freuchie. Comyn of Freuchie, little liking such a settlement in his

immediate neighbourhood, tried to dislodge the trespassers, but without

result. Then the MacGregor Chief appeared upon the scene with an armed

following and demanded his daughter. He arrived at night, and was received

by his astute son-in-law with much respect and hospitality. As the feast

went on at the mouth of the cavern, Grant so arranged the comings and

goings of his men in the torchlight and among the woods that his

father-in-law was impressed with what appeared to be the considerable size

of his following, and, changing his mind with regard to the desirability

of the match, freely forgave the young couple. Forthwith Grant proceeded

to turn his father-in-law’s friendship to account. He told him of the

attacks made upon him by Comyn of Freuchie, and persuaded him to help in a

reprisal. Before morning the united forces of Grant and MacGregor made an

attack on Freuchie, slew the Comyn chief, and took possession of the

castle. As a token and memento of the occurrence, the skull of Comyn is

carefully preserved at Castle Grant to the present day.

The castle did not

immediately change its name, for in a charter under the Great Seal in 1442

Sir Duncan Grant is described as "Dominus de eodem et de Freuchie."

A succeeding chief, Sir Ian, joined the Earls of Huntly and Mar with his

clan in 1488 in support of James III. against his rebellious nobles; so by

that time the Grants had become a power to be reckoned with. Like most of

the Highland clans they had their own story of fiery feud and bloody raid.

One of the chief quarrels in which they were engaged remains notable from

the fact that it led directly to a notorious historical event, the

slaughter of the Bonnie Earl of Moray at Dunibristle on 7th February,

1592. The trouble began when the Earl of Huntly, Chief of the Gordons and

of the Catholics of the north, finding himself in danger among the

Protestant faction at court, retired to his estates and proceeded to erect

a castle at Ruthven in Badenoch, not far from the Grant country. This

seemed to the Grants and Clan Chattan to be intended to overawe their

district, and difficulties arose when the members of Clan Chattan, who

were Huntly’s vassals, refused to fulfil their obligations to furnish

the materials for the building. About the same time John Grant, the Tutor,

or trustee, of Ballindalloch, refused certain payments to the widow of the

late laird, a sister of Gordon of Lesmore. In the strife which followed a

Gordon was slain, and as a consequence the Tutor was outlawed and

Ballindalloch was besieged and captured by Huntly. That was on 2nd

November, 1590. Forthwith the Grants and. MacIntoshes sought the

protection of the Earls of Athol and Moray. They refused Huntly’s

summons to deliver up the Tutor, and when surprised at Forres by the

sudden appearance of Huntly, fled to the Earl of Moray’s castle of

Darnaway. Here another Gordon was shot by one of Moray’s servants. This

bred bad blood between the two earls, and later, when the Earl of Bothwell,

after an attempt on the life of Chancellor Maitland, was said to be

harboured by Moray in his house of Dunibristle, Huntly willingly accepted

a commission to attack that place. Here again a Gordon was mortally

wounded, and, on the Earl of Moray fleeing along the shore, he was pursued

by the brothers of the two slain men, and promptly put to death. Among

other acts of vengeance Huntly sent a force of Lochaber men against the

Grants in Strathspey, killing eighteen of them, and laying waste the lands

of Ballindalloch. Afterwards, when the young Earl of Argyll was sent to

attack Huntly, the Grants took part with him at the battle of Glenlivet,

and Argyll’s defeat there was mainly owed to the action of John Grant of

Gartenbeg, one of Huntly’s vassals, who, as arranged with Huntly,

retired with his men at the beginning of the action, and thus completely

broke the centre and left wing of Argyll’s army.

The most notable feature in

the annals of the clan during the first half of the seventeenth century

was the career of James Grant of Carron. The determining factor in the

career of this notable freebooter was an event which had happened some

seventy years previously. This was the murder of John Grant of

Ballindalloch by John Roy Grant of Carron, a son of John Grant of Glen

Moriston, at the instigation of the Laird of Grant, who, it is said, had

conceived a grudge against his kinsman. A feud between the Grants of

Carron and the Grants of Ballindalloch was the result. In the course of

this feud, at a fair at, Elgin about the year 1625, one of the Grants of

Ballindalloch knocked down and wounded Thomas Grant, one of the Carron

family. The brother of Thomas, James Grant of Carron, attacked the

assailant and killed him on the spot. At the instance of Ballindalloch,

James Grant was cited to stand trial, and, as he did not appear, was

outlawed. In vain the Laird of Grant tried to reconcile the parties, while

James Grant offered money compensation, and even the exile of himself.

Nothing but his blood, however, would satisfy Ballindalloch, and, driven

to despair, with his life every moment in jeopardy, James Grant finally

collected a band of broken men from all parts of the Highlands, and set up

as an independent freebooter. His career was that of another Gilderoy, or

the hero of the famous MacPherson’s Rant. Lands were wasted by him and

men were slain, and Ballindalloch, having killed John Grant of Carron, the

nephew of the freebooter, was himself forced to flee to the North of

Scotland. At last, at the end of December, 1630, a party of Clan Chattan

surprised James Grant at Auchnachayle in Strathdon by night, when after

receiving eleven wounds and seeing four of his party killed, the cateran

was taken prisoner, sent to Edinburgh for trial, and imprisoned in

Edinburgh Castle.

About the same time the

famous feud occurred between Gordon of Rothiemay and Crichton of

Frendraught, which ended in the burning of Frendraught, with Lord Aboyne,

the Marquess of Huntly’s son, and several of his friends. Rothiemay had

been helped in the feud by James Grant, and it was said the latter had

been in treaty to undertake the burning of the mansion.

On the night of 15th

October, 1632, the freebooter escaped from Edinburgh Castle by descending

on the west side by means of ropes furnished him by his wife or son, and

fled to Ireland. Presently, however, it was known that he had returned,

and Ballindalloch, setting a watch upon his wife’s house at Carron,

almost secured him. The freebooter, however, shot the chief assailant, one

Patrick MacGregor, and escaped. Presently by a stratagem he managed to

seize Ballindalloch himself, and kept him for twenty days prisoner in a

kiln near Elgin. Ballindalloch finally escaped by bribing one of his

warders, and as a result several of James Grant’s accomplices were sent

to Edinburgh and hanged.

The cateran’s final

outrage was the surprise and slaughter of two other friends of

Ballindalloch, who had received money to kill him. A few days later Grant

and four of his associates, finding themselves in straits in Strathbogie,

entered the house of the common hangman, unaware of his profession, and

asked for food. The man recognised them, and the house was surrounded; but

the freebooter made a stout defence, killing three of the besiegers, and

presently, with his brother Robert, effected his escape, though his son

and two other associates were captured, carried to Edinburgh, and

executed. This took place in the year 1636, and as no more is heard of

James Grant, it may be presumed that, like Rob Roy MacGregor, a century

afterwards, he finally died in bed.

A few years later, on the

outbreak of the Civil War, when the Marquess of Montrose raised the

standard of Charles I. in the Highlands, he was joined by James, the

sixteenth Chief of the Grants, with his clan, who fought valiantly in the

royal cause.

Twenty-one years later

still, in 1666, occurred a strange episode which added a large number of

new adherents to the "tail" of the Chiefs of Grant. As recorded

in a famous ballad, the Farquharsons had attacked and slain Gordon of

Brackly on Deeside. To avenge his death the Marquess of Huntly raised his

clan and swept up the valley. At the same time his ally, the Laird of

Grant, now a very powerful chief, occupied the upper passes of the Dee,

and between them they all but destroyed the Farquharsons. At the end of

the day Huntly found two hundred Farquaharson orphans on his hands. These

he carried home and kept in singular fashion. A year afterwards Grant was

invited to dine with Huntly, and when dinner was over, the Marquess

proposed to show his guest some rare sport. He took him to a balcony

overlooking the kitchen of the castle. Below they saw the remains of the

day’s victuals heaped in a large trough. At a signal from the chief cook

a hatch was raised, and there rushed into the kitchen like a pack of

hounds, yelling, shouting, and fighting, a mob of half-naked children, who

threw themselves upon the scraps and bones, struggling and scratching for

the base morsels. "These," said Huntly, are the children of the Farquharsons we slew last

year." The Laird of Grant, however, was a

humane man; he begged the children from the Marquess, took them to

Speyside, and reared them among the people of his own clan, where their

descendants were known for many a day as the Race of the Trough.

At the Revolution in 1689,

Ludovic,

the seventeenth Chief, took the side of William of Orange, and after the

fall of Dundee at Killiecrankie, when Colonel Livingstone hastened from

Inverness to attack the remnants of the Jacobite army under Generals

Buchan and Cannon, at the Haughs of Cromdale in Strathspey, he was joined

by Grant with 600 men. The defeat of the Jacobites on that occasion, and

the capture of Ruthven Barracks opposite Kingussie, gave the final blow to

the cause of King James in Scotland.

Again, during the Jacobite Rebellion of

1745, there were 800 of the clan in arms for the

Government, though they took no active part against Prince Charles Edward.

The military strength of the Grants was then estimated at 850 men.

In the middle of the eighteenth century Sir Ludovic

Grant, Bart., married Margaret, daughter of James Ogilvie, fifth Earl of

Findlater and second Earl of Seafield, and through that alliance his

grandson, Sir Lewis Alexander Grant, succeeded as fifth Earl of Seafield

in 1811. Meantime Sir Ludovic’s son, Sir James Grant, had played a

distinguished part on Speyside. He it was who in 1776, in connection with

extensive plans for the improvement of the whole region of middle

Strathspey, founded the village of Grantown, which has since become so notable a resort. The same laird in

1793, two months after the declaration of war against

this country by France, raised a regiment of Grant fencibles, whose

weapons now cover the walls of the entrance hall in Castle Grant.

An unfortunate circumstance in the history of this

regiment was the mutiny which took place at Dumfries. The trouble arose

from a suspicion that the regiment, which had been raised for service in

Scotland only, was about to be dispatched overseas. A petty dispute having

arisen, some of the men were imprisoned, and were released by their

comrades in open defiance of the officers. This constituted a mutiny. In

consequence the regiment was marched

to Musselburgh, where a corporal and three privates found guilty of mutiny

were condemned to death. On 16th July, 1795, the

four men were marched to Gullane links. There they were made to draw lots, and two of

them were shot.

On Sir Lewis Alexander Grant succeeding to the earldom

of Seafield in 1811 he added the Seafield family name of Ogilvie to his

own patronymic. The earldom had originally been granted to James, fourth

Earl of Findlater, in 1701, in recognition of his distinguished services as

Solicitor-General, Secretary of State for Scotland, Lord Chief Baron of

the Exchequer, and High Commissioner to the General

Assembly, and it has received additional lustre from its connection with

the ancient Chiefs of Grant. [The first recipient of the title was at

the time Lord Deskford, second son of George Ogilvie, third Earl of

Findlater.

It was he who, at the Union, when the Scottish Parliament

rose for the last time, exclaimed, "This is an end of an auld sang!"]

The grandson of the first earl of the name of Grant,

John Charles, who succeeded as seventh Earl in 1853, married the Honourable Caroline Stuart, youngest

daughter of the eleventh Lord Blantyre. With the consent of his son he

broke the entail of the Grant estates, and that son, Ian Charles, the

eighth Earl, at his death unmarried, bequeathed these estates to his

mother. It was the seventh and eighth Earls who carried out the vast

tree-planting operations in Strathspey which have changed the whole

climate of the region, restoring its ancient forest character, and

rendering it the famous health resort it is

at the present day. Meanwhile no fewer than three earls succeeded to the

title without possession of the estates. The first of these was Lady

Seafield’s brother-in-law, James, third son of the sixth Earl, who was

member of Parliament for Elgin and Nairn from 1868 to 1874. Francis William, the son of this earl, born in

1847, had emigrated in early life to New Zealand. At that time the

possibility of his succeeding to the title appeared exceedingly remote.

On the death of the eighth Earl, the emigrant’s father succeeded to

the title, and the emigrant himself became Viscount Reidhaven. He

married a daughter of Major George Evans of the 47th

regiment, and though he succeeded to the title of earl in 1888, it made

no difference in his fortunes, and he died six months later. His son,

the next holder of the title, was eleventh Earl of Seafield and twenty

fourth Chief of Clan Grant. His lordship’s home-coming to Castle Grant

was the occasion of an immense outburst of enthusiasm on the part of the

clan, and afterwards, residing among his people, he and his countess did

every thing to endear themselves to

the holders of their ancient and honourable name.

The Earl died on active

service in the Great War, and while his daughter succeeded to the Grant

estates and the title of Seafield, his brother inherited the Barony of

Strathspey and the chiefship of the clan. Lord Strathspey, with his wife,

son and daughter, returned to New Zealand in 1923.

The Grant country stretches

from Craigellachie above Aviemore to another Craigellachie on the Spey

near Aberlour. It is a country crowded with interesting traditions. Many a

time the wild bands of warriors have gathered on the shores of the little

loch of Baladern on its southern border, and the slogan of "Stand

fast, Craigellachie! "has been shouted in many a fierce mêlée. Even

as late as 1820, during the general election after the death of George

III., the members of the clan found occasion to show their mettle. Party

feeling was running high, and a rumour reached Strathspey that the ladies

of the Chief’s house had suffered some affront at Elgin at the instance

of the rival clan Duff. Next morning there were 900 Strathspey men, headed

by the factor of Seafield, at the entrance to the town, and it was only by

the greatest tact on the part of the authorities that a collision was

prevented. Even to the present day the old clan spirit runs strong on

Speyside, and the patriotism of the race has been shown by the number of

men who enlisted to defend the honour of their country in the great war of

1914 on the plains of France.

Septs of Clan Grant:

Gilroy, MacIlroy, MacGilroy.

Grants of Glenmoriston

BADGE: Giuthas (pinus sylvestris) pine.

OF

the Siol Alpin, or Race of Alpin, descended from that redoubtable but ill-fated

King of Scots of the ninth century, there are to be counted Clan Gregor, Clan

Grant, Clan Mackinnon, Clan MacNab, Clan Macfie, Clan MacQuarie, and Clan

MacAulay. These, therefore, have at all times claimed to be the most ancient and

most honourable of the Highland clans, and have been able to make the proud

boast " Is rioghal mo dhream"—Royal

is my race. It was unfortunate for the Siol Alpin that at no time were all the

clans which it comprised united under a single chief. Had they been thus united,

like the great Clan Chattan confederacy, they might have achieved a greater

place in history, and might have been saved many of the disasters which overtook

them. OF

the Siol Alpin, or Race of Alpin, descended from that redoubtable but ill-fated

King of Scots of the ninth century, there are to be counted Clan Gregor, Clan

Grant, Clan Mackinnon, Clan MacNab, Clan Macfie, Clan MacQuarie, and Clan

MacAulay. These, therefore, have at all times claimed to be the most ancient and

most honourable of the Highland clans, and have been able to make the proud

boast " Is rioghal mo dhream"—Royal

is my race. It was unfortunate for the Siol Alpin that at no time were all the

clans which it comprised united under a single chief. Had they been thus united,

like the great Clan Chattan confederacy, they might have achieved a greater

place in history, and might have been saved many of the disasters which overtook

them.

After the young Chief of the Grants, with the

help of his father-in-law, the Chief of MacGregor, had established his

headquarters at Freuchie, now Castle Grant, by the slaughter and expulsion of

its former owners, the Comyns, the race of the Grants put forth more than one

virile branch to root itself on fair Speyside and elsewhere. Among these were

the Grants of Ballindalloch, the Grants of Rothiemurchus, the Grants of Carron,

and the Grants of Culcabuck. In the days of James IV., the Laird of Grant was

Crown Chamberlain of the lordship of Urquhart on Loch Ness, which included the

district of Glenmoriston. In 1509, in the common progress of events, the

chamberlainship was converted into a baronial tenure, and the barony was granted

to John, elder son of the Chief. The change, however, instead of aggrandising

the family, threatened to entail an actual loss of the territory, for John died

without issue, and the barony, under its new tenure, reverted to the Crown.

A similar, but much more disastrous set-back

was that which happened about the same time to the ancient family of Calder or

Cawdor, near Nairn. In the latter case the old Thane resigned his whole estates

to the Crown, and had them conferred anew on his second son John, and shortly

afterwards John died, leaving an only child, a girl, Muriel, who ultimately, by

marriage, carried the thanedom away from the Cawdors, into possession of the

Campbells, its present owners.

The case of Glenmoriston was not

so irretrievable, for the barony was acquired by Grant of Ballindalloch. The

latter in 1548 disposed of it to his kinsman John Grant of Culcabuck, who

married a daughter of Lord Lovat, and John Grant’s son Patrick established

himself in the district, and became the ancestor of the Grants of Glenmoriston.

It is from this Patrick Grant, first of the long line of lairds, that the clan

takes its distinctive patronymic of Mac Phadruick.

Patrick’s son John, the second

chief, married a daughter of Grant of Grant, and built the castle of

Glenmoriston, from which fact he is known in the tradition of his family as Ian

nan Caisteal—John of the Castle.

In James VI.’s time

Glenmoriston had its own troubles, arising from an act which, one would have

supposed, would have been looked upon by any Scotsman as a warrant against

oppression. Clan Chattan, it appears, had been faithful friends and followers of

the Earls of Moray, and in particular had been active in avenging against the

Earl of Huntly, the death of the "Bonnie Earl" at Donibristle on the

Forth. For these services they had received valuable possessions in Pettie and

Strathnairn. But presently the Bonnie Earl’s son became reconciled to Huntly,

and married his daughter; then, thinking he had no more need of Clan Chattan,

proceeded to take back these gifts. By way of retaliation, in 1624 some 200

gentlemen and 300 followers of the clan took arms and proceeded to lay waste the

estates of the grasping Moray. The latter failed to disperse them, first with

three hundred men from Menteith and Balquhidder, and afterwards with a body of

men raised at Elgin. He then went to London and induced James VI. to make him

Lieutenant of the North. Returning with new powers, the Earl issued letters of

intercommuning against Clan Chattan, prohibiting all persons from harbouring,

supplying, or entertaining members of the clan, under severe penalties. Having

thus cut off the clansmen’s means of support he proceeded to make terms with

them, offering them pardon on condition that they should give a full account of

the persons who had sheltered and helped them in their attempt. This Clan

Chattan basely proceeded to do, and the individuals who had rendered them

hospitality and support were summoned to the Earl’s court and heavily fined,

the fines going into Moray’s own pocket. A striking account of the

proceeding is furnished by Spalding the historian. He relates how "the

principal male-factors stood up in judgment, and declared what they had gotten,

whether meat, money, clothing, gun, ball, powder, lead, sword, dirk, and the

like commodities, and also instructed the assize in each particular what they

had gotten from the persons panelled—an uncouth form of probation, where the

principal malefactor proves against the receiptor for his own pardon, and honest

men, perhaps neither of the Clan Chattan’s kin nor blood, punished for their

good will, ignorant of the laws, and rather receipting them more for their evil

nor their good. Nevertheless the innocent men, under colour of justice, part and

part as they came in, were soundly fined in great sums as their estates might

bear, and some above their estates was fined, and every one warded within the

tolbooth of Elgin, till the last mite was paid."

Among those who thus suffered was

John Grant of Glenmoriston. The town of Inverness was also mulcted, and the

provost, Duncan Forbes, and Grant, both went to London to lay the matter before

the king. They did this without success, however, and in the end had to submit

to the Earl of Moray’s exactions.

In the latter half of the

seventeenth century, John, the sixth Chief of Glenmoriston, married Janet,

daughter of the celebrated Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, and earned the name of

Ian na Chreazan by building for himself the rock stronghold of Blary. Like Sir

Ewen Cameron, his father-in-law, he raised his clan for the losing cause of

James VII. and II., and fought under Viscount Dundee at Killiecrankie. The clan

was also out under the Earl of Mar in the rising for "James VIII. and

III." in 1715, and as a result of that enterprise the chief suffered

forfeiture. The estates, however, were restored in 1733.

Patrick, the ninth chief, who

married Henrietta, a daughter of Grant of Rothiemurchus, undeterred by the

misfortune which had overtaken his family on account of its previous efforts in

the Jacobite cause, raised his clan for Prince Charles in the autumn of 1745. He

was not in time to see the raising of the Prince’s standard at Glenfinnan, but

he followed hotfoot to Edinburgh, where his clansmen formed a welcome

reinforcement on the eve of the battle of Prestonpans. So eager was he, it is

said, to inform Charles of the force he had brought to support the cause, that

he did not wait to perform his toilet before seeking an interview. Charles is

said to have thanked him warmly, and then, passing his hand over the rough chin

of the warrior, to have remarked merrily that he could see his ardour was

unquestionable since it had not even allowed him time to shave. Glenmoriston

took the remark much amiss. Greatly offended, he turned away with the remark,

"It is not beardless boys that are to win your Highness’ cause!"

This, however, was not the last

the Prince was to know of Glenmoriston, or the last that Glenmoriston was to

suffer for the cause of the Prince. When Culloden had been fought, and the

Jacobite cause had been lost for ever, Charles in the darkest hours of his fate,

wandering a hunted fugitive among the glens and mountains, found a shelter with

the now famous outlaws, the Seven Men of Glenmoriston. Only one of them was a

Grant, Black Peter, or Patrick, of Craskie, but it was in Grant’s country, and

the seven men, any one of whom could at any moment have enriched himself beyond

the dreams of avarice by betraying the Prince and earning the £30,000 set by

Government upon his head, proved absolutely faithful. These men had seen their

own possessions destroyed by the Red Soldiers because of the Prince, and they

had seen seventy of the men of Glenmoriston, who had been induced by a false

promise of the Butcher Duke of Cumberland, at the intercession of the Laird of

Grant, to march to Inverness and lay down their arms, ruthlessly seized and

shipped to the colonies as slaves, but they treated Charles with Highland

hospitality in their caves of Coiraghoth and Coirskreaoch, and for that the

Seven Men of Glenmoriston will have an honourable place for ever in Scottish

history.

While the Prince was in hiding in

the Braes of Glenmoriston, two of the Seven Men, out foraging for provisions,

met Grant of Glenmoriston himself. The chief had had his house burned and his

lands pillaged for his share in the rising, and he asked the two men if they

knew what had become of the Prince, who, he heard, had passed the Braes of

Knoydart. Even to him, however, they did not reveal the secret of the royal

wanderer’s hiding. And when they asked the Prince himself whether he would

care to see Glenmoriston, Charles said he was so well pleased with his present

guard that he wanted no other.

In the first bill of attainder

for the punishment of those who had taken part in the rebellion the name of

Grant of Glenmoriston was included, but, probably at the instance of Lord

President Forbes, it was afterwards omitted, and the chief retained his estates.

Patrick Grant’s son and

successor, John, held a commission in the 42nd Highlanders, and highly

distinguished himself during the brilliant service of that famous regiment in

India, rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He died at Glenmoriston in

1801. His elder son died while a minor, and was succeeded by his brother James

Murray Grant. This chief married his cousin Henrietta, daughter of Cameron of

Glennevis, and in 1821 succeeded to the estate of Moy, beside the Culbin Sands

in Morayshire, as heir of entail to his kinsman Colonel Hugh Grant.

Thanks to James

Pringle Weavers for the following information

GRANT: This clan are presumed to descend from Sir Laurence le Grant, Sheriff of Inverness c.1258, although a continuum of chiefship cannot be established until about 1453 when Sir Duncan Grant became 1st Laird of Freuchie. Successive chiefs consolidated vast lands in Strathspey and important cadet families developed at Ballindalloch, Gartinbeg, Kinchurdie, Tullochgorm and Rothiemurchus. More independent branches flourished at Corriemony, Sheuglie, and Glenmoriston, in Inverness-shire, and at Monymusk in Aberdeenshire. The lands of the 8th Laird of Freuchie were erected into the Regality of Grant in 1694, and the family thereafter bore the form 'Grant of Grant'. By marraige, and according to the laws of tanistry, descendants of the 8th Laird inherited the chiefship of the Colquhoun on the western shores of Loch Lomond with the proviso that the respective honours should remain distinct. The chiefs espoused the Hanoverian cause in the 1715 and 1745 Risings, but the Grants of Glenmoriston, and many in Glenurquhart, supported the Jacobites. In 1793, Sir James Grant raised the 1st Fencible Regiment, and the 97th Regiment the following year. His son, Lewis Alexander, inherited the estates and honours of the Earl of Seafield, and in 1858, the 7th Earl was created Baron Strathspey. Ian, 8th Earl, was succeeded by his uncle James, who was created Lord Strathspey in 1884. In 1704 the Grant clansmen were instructed to be ready to assemble in "tartan of red and greine sett broad springed" - the first reference to the clan's rich tartan heritage, which is further evidenced by the wealth of clan portraiture depicting its use. The red tartan recorded at Lyon Court in 1946 is much older, for it appears in a pattern book of 1819 with the note that 200 yards had been ordered by Patrick Grant of Redcastle as the tartan of his clan. The Black Watch sett is also worn as a hunting or "undress" tartan, such recalling the Grant involvement at the founding of that Regiment. The Wilson pattern book of 1819 also shows a most pleasing 'Hunting' pattern well worthy of revival.

|