|

As part of the inaugural Perthshire

Archaeology Week, on the 15 June 2003 Mark Hall, of Perth Museum and Art

Gallery led an enthusiastic party around the early medieval landscape of

Struan. We looked at three elements in particular: 1.The Garry-Errochty

river junction and placenames; 2.Struan Kirk and Kirkyard; 3.Struan mound.

This article is by way of a brief account of that walk-and-talk.

The Garry-Errochty river junction and

place names.

We began our historical exploration

where the waters of the River Garry and the Errochty Water meet and thus

define a rather peninsula-like piece of land on which Struan Kirk stands.

Struan drives from the Gaelic word sruthan, meaning 'place of

streams, confluence' and so is an eloquent description of the meeting of

the Garry and the Errochty. The word Errochty is also of Gaelic origin and

means 'Assembly place'. Garry, incidentally, may derive from the Gaelic

for thicket or den or it may be from the name Garaidh, an Irish hero. That

these names have a Gaelic origin suggests that they were named at the time

of Gaelic settlement from the West Coast (present day Argyll, in the past

Dalriada) during the 7th/8th century, giving rise to the Gaelic kingdom of

Atholl. The place name Struan may seem no more than a prosaic description

of a place where two rivers meet but it is clear that such places had a

notable value to early medieval peoples. A Pictish or British equivalent,

Aber, is one of the commonest surviving such place name elements,

meaning 'at the confluence of' (e.g Aberfeldy, Abernethy and Aberdeen).

The name Struan occurs much more rarely (in part because river names often

retain their older names even during periods of extensive immigration) but

there is a further example in Perthshire, with the variant spelling of

Strowan, near Crieff. In the past Strowan and Struan were clearly

interchangeable spellings of the same word: both are at various times used

to name both places. What is particularly interesting about Strowan and

Struan is that both are places where the meeting of the rivers (in

Strowan's case the Earn and the Glascorrie Burn) are marked by the

presence of an early medieval church site and early medieval or Pictish

sculpture.

Struan Kirk and Kirkyard

Although the present Kirk is a 19th

century rebuild there are several clues to the presence of a much earlier

Church on the site. The circular shape of the churchyard: although it does

not appear circular today it is clear from old maps that the churchyard

has gradually been reduced in size and given a rectangular shape. A

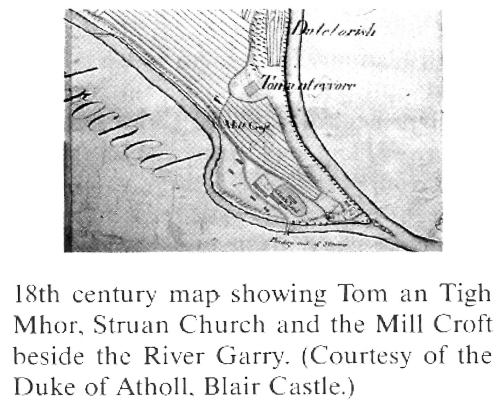

probably 18th century map of Struan (in Blair Castle Archives) in

particular suggests that the churchyard was formerly much more rounded in

shape. As a rule of thumb a round or circular churchyard indicates an

early medieval date for the origin of that churchyard. The roundness or

circularity may have been a reflection of the near universal idea of the

sacred circle.

The dedication to St Fillan: the

origins and identity of St Fillan are obscure. There are approximately 20

saints with the name Fillan commemorated in early Irish written sources.

Certainly by the 9th century there was a strong cult of St Fillan in what

is now West Perthshire, with a particular focus in Glen Dochart and Upper

Strathearn. The Fillan in question seems to have been someone born in

Ireland, possibly of royal lineage, and who came to Pictland as a

missionary. The cult of St Fillan continued through the later medieval

period and was certainly boosted by the patronage of King Robert I. Saints

calendars from the end of the Middle Ages indicate two Fillans in

Scotland, with feasts on 20 June and 9 January. These could though be a

confusion of the birth and death dates (important because it marked the

point at which sainthood was gained) of the same Fillan. Allied to the

dedication is a long established fair named (in the Gaelic) after St

Fillan, Feill Faolan. This was held on the first Friday after New Year's

Day, probably to coincide with the 9 January feast day. The fair was held

on the field west of the Church, known as croft an' taggart or the

'Priest's croft/field'. From the early medieval period it was common for

there to be a strong link between fairs and the church and this seems to

be a good example of the practice.

There is one more piece of evidence

relating to St Fillan, an early medieval handbell named after the saint

(though at times it was also known more affectionately as the Buidhean, or

'the little yellow one'). Such cast, iron and bronze hand-bells were a

common feature of the early church and several examples survive from

Perthshire. The bell is unlikely to have been associated directly with St

Fillan and should be seen as part of the cult of St Fillan that was

practised in Struan in the 9th/10th/11th centuries. So it is St Fillan's

bell in the sense that it belonged to the church and community of St

Fillan in Struan. It was kept by the church and remained in some kind of

use (possibly as a 'deid-bell' and so chimed when a parishioner died or at

the head of a funeral procession) until the 19th century when William

McInroy of Lude gave the church a new bell in exchange for St Fillan's,

which he kept at Lude House. There it remained until 1939 when the house

and its contents were auctioned-off. The bell was purchased by

philanthropist whisky-millionaire A K Bell on behalf of Perth Museum and

Art Gallery. It is currently on display in the Human History Gallery of

the Museum.

Early medieval sculptures: also of

key relevance to our understanding of the development of Christianity in

the area is the survival of three Pictish or early medieval sculptures.

All have been found, at various times, in the churchyard. Two of them are

simple, quartzite-slate pillar-like stones incised with simple crosses.

The first of these was found in 1868 during the digging of a grave. It

stands in the middle of the churchyard and with careful inspection, its

two crosses can still be seen. The second has been known since the end of

the 19th century and is built into the west wall of the churchyard. It is

difficult to find and the cross has suffered some damage since it was

recorded at the end of the 19th century. Such carvings are generally seen

as a mark of Christian missionary work in what is now Scotland between the

6th and 9th centuries. Use as burial markers are a somewhat remoter

possibility. The third piece of sculpture was known by the 19th century

when it stood in the churchyard, leaning against the south wall of the

church. In the early 1970s, it was moved inside the church, where it now

stands, for its greater protection. It is a large, irregularly shaped slab

of schistose slate incised on one face with Pictish symbols. Clearly

visible is a double-disc and a z-rod but the symbol next to it has been

largely lost and its identity cannot be determined. The first drawing of

the stone is that done for John Stuart's The Sculptured Stones of

Scotland, published in 1856. Although the drawing was published upside

down it records additional details now lost, suggesting that the only

partially surviving second symbol may have bee the so-called 'flower'

symbol and that there was a third symbol that was even then indistinct and

certainly lost by the time Allen and Anderson's Early Christian Monuments

of Scotland was published in 1903. These so-called Pictish symbols are a

unique feature of early medieval sculpture in Scotland but their precise

meaning remains far from clear. There are many theories that try to

explain them: family badges, territory markers, burial markers, marriage

or alliance signifiers, some other form of specific symbolic language, a

reaction to the process of Christian conversion etc; but the prize of

certainty remains elusive. The main geographical focus for the symbol

stones is what might be termed Eastern Pictland, i.e. from the Forth

northwards and excluding the West Highlands and Islands. In this area

there are currently some 160 known sets of symbols. The z-rod (really a

backwards z) and the double-disc occurs around 51 times as a pair (and

each also occurs as separate symbols). Most to them are further north and

east of Struan, notably in Aberdeenshire.

Struan mound.

The third crucial element in the

landscape around Struan Kirk is the mound, which lies a few yards to the

north-west of the Kirk. This mound has long been known as Tom an Tigh

Mhoir - the mound of the great house. This Gaelic name may however be of

comparatively recent origin, to explain the mound, the original purpose of

which had been forgotten. In 1890 the antiquary MacIntosh-Gow recorded

that on top of the mound the presence of clearly visible building

foundations, said to be the remains of a house built by a local Laird but

never finished apparently because a neighbour over the river Garry built a

much higher castle. However the nature of the mound is such that if anyone

should try and rather foolishly build on it they would soon find that they

had no room and no weight bearing stability.

The mound measures approx. 20 foot

high and is approx. 75ft in diameter across the base and 55ft across the

top. It is generally held to be an early stronghold of the Chiefs of Clan

Donnachaidh and in a survey of mottes in Scotland published in 1972 (and

republished in 1985) it is accepted as being a motte. However there are a

number of factors that suggest that it may not be a motte at all but

rather an assembly mound. The factors that work against its being a motte

can be listed as follows:

Size: superficially it does look

quite large but the available area to be built on is rather small when

compared with other mottes and when this is set alongside the subsequent

points it is even more telling.

Ditch: there is no defensive ditch

surrounding the mound nor any sign that there ever was one. There is a

partial ditch of very shallow depth which runs around the northern

perimeter which seems rather like a later addition possibly for drainage

purposes?

Location: the mound is built-up

from the steep bank of the river Garry, which would make it structurally

unsound - especially if built upon - particularly during flooding and high

river levels.

Spring: the sloping river-bank on

which it is built is also the location of a spring, making it even more

susceptible to slippage. This spring was long revered as the well of St

Fillan and tradition records that a wooden statue of St Fillan (kept in

the Kirk) was ritually dipped in the well at times of drought in the hope

of bringing rain. In the early 18th century the then incumbent Minister

John Hamilton, found this to be an unpalatable vestige of Catholic belief

and so had the statue smashed and thrown into the Garry.

There are still difficulties with

identifying what the mound was used for and it clearly did seem to have

supported some form of structure as lines of walls can still be seen on

the mound. However it is possible that these relate to the construction of

the mound itself or to a small building added at a much later date or a

building started but abandoned. It is a strong possibility that a

structure that has stood for as many centuries as the mound has had more

than one episode of use and that what we see today is a conflation of use,

re-use and adaptation. Given its physical appearance its location and its

landscape context (including the early church and the placenames) it seems

highly likely that the mound was originally constructed (or adapted) as a

mound of assembly and /or judgement. Such mounds (sometimes known as moot

hills) can be purpose built or adaptations of existing man-made or natural

mounds. Such mounds of assembly are often associated with a church and

seem to occur quite widely from the 9th/10th century. There seem to be two

(not always) distinct traditions, Scandinavian (for example Govan on the

Clyde and Tynwald on the Isle of Man) and Irish/Gaelic/British (for

example Scone, Perthshire and Tara in Ireland). There also seems to be a

wide range of mound sites, some beside churches, some with churches upon

them and their precise subtleties of meaning require further study.

Examples include Kirkinch (nr. Meigle), Angus; Eassie, Angus; Caputh,

Perthshire; and La Hogue Bie, Jersey (where the church is built on top of

a Neolithic burial mound). Caputh is notable for having been a moot-hill

that was then use, from the 16th century, as the site for a new parish

church and burial ground. It is close to Murthly (which means 'big

mound'), the two places being on opposite banks of the river Tay, and from

where three pieces of early medieval sculpture have been found during the

last 100 years or so. If such sites also came to be linked with local

lordships it is possible that the mound at Struan may be suggestive of an

early thanage there, part of the lordship of Atholl.

As many readers of this Annual will know

Struan is part of the heartland of the Robertsons/Clan Donnachaidh.

Certainly they would have been important patrons of Struan Kirk in the

later medieval period (and beyond), would have practised the cult of St

Fillan and may possibly have made some use of the mound. However the

purpose of this short article has been to show that Struan has a much

longer history than its association with the Robertsons and the Clan's

first chief, Fat Duncan. Five hundred years and more before Duncan Pict

and Scot were learning to live with each other, being converted to and

practising Christianity and establishing their mechanisms of governance

and social control.

by Mark Hall

Struan Symbol Stone

Further Reading

For those interested many of the points

raised in this account can be followed up in the following books and

articles.

J Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson, The

Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, 2 volumes, Pinkfoot press,

Balgavies, 1993 (originally 1903). [p.285-6 for the symbol stone; p.343

for the cross-incised stones].

George F Black The Surnames of Scotland,

originally published 1946, reprinted Birlinn 1996. [Concise entries for

Robertson and Donnachie].

Cormac Bourke, The handbells of the

early Scottish church, in Proceedings of the Antiquaries of Scotland 113

(1983), 464-8.

Stephen Driscoll, The Archaeological

Context of Assembly in Early medieval Scotland - Scone and its Comparanda,

in A Pantos and S Semple Assembly Places and Practices in medieval Europe,

forthcoming.

Katherine Forsyth, Some thoughts on

Pictish Symbols as a formal Writing System, in David Henry the worm the

germ and the thorn Pictish and related studies presented to Isabel

Henderson, Pinkfoot press, Balgavies, 1997.

Sally Foster Picts, Gaels and Scots,

Historic Scotland/Batsford, London, 1996.

Mark Hall, Isabel Henderson and Ian G

Scott, The Early medieval Sculpture from Murthly, Perthshire: An

Interdisciplinary Look at People, Politics and Monumental Art, forthcoming

in the proceedings of 2003 conference Able Minds and Practised Hands.

[Includes a discussion of mounds and their association with churches].

James Macintosh Gow, Holiday Notes in

Athole, Perthshire, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of

Scotland XII (1890), p.382-87. [Struan at p.383-85].

Mark Hall, Katherine Forsyth, Isabel

Henderson, Ross Trench-Jellicoe and Angus Watson, Of Makings and Meanings:

Towards a Cultural Biography of the Crieff Burgh Cross, Strathearn,

Perthshire; in Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal 6(2000) 154-88.

[Includes a discussion of the Strowan/Struan place name and a site

comparison].

George and Isabel Henderson, The Art of

the Picts. Sculpture and Metalwork in Early medieval Scotland, forthcoming

in 2004.

Isabel Henderson Early Christian

Monuments of Scotland Displaying Crosses and No Other Ornament, in Alan

Small The Picts A New Look at Old Problems, Dundee 1987. [Key introduction

to the subject of simple cross-incised stones].

John Kerr, Church and Social History of

Atholl, Perth & Kinross Libraries, Perth, 1998. [Useful overview of the

development of the parish of Struan]

John Kerr, The Robertson Heartland,

reprinted from the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness LVI, in

1992. [Useful overview of the Struan area but with a more detailed

coverage of the Robertson link]

Alexander Laing, Notice of Early

Monuments in the Parish of Strowan, Blair Athole, in Proceedings of the

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland VII (1868), p.442-4. [Descriptions of

the cross-incised stones].

Alastair Mack, Field Guide to the

Pictish Symbol Stones, Pinkfoot Press, Balgavies, Angus 1997. [p.6 for the

double-disc and z-rod symbol; p.21-2 for the flower symbol].

E H Nicoll A Pictish Panorama, Pinkfoot

Press, Balgavies, 1995. [A useful introduction to things Pictish].

David Stuart, The Sculptured Stones of

Scotland, volume II, Aberdeen, 1856. [Struan symbols stone is plate CII

no. 2].

Simon Taylor, The Cult of St Fillan in

Scotland, in Thomas Liszka and Lorna Walker The North Sea World in the

Middle Ages, Studies in the Cultural history of North-Western Europe, Four

courts Press, Dublin, 2001. [Detailed assessment of the identity and cult

of St Fillan].

Charles Taylor, The Early Christian

Archaeology of North Britain, Oxford University Press (for Glasgow

University), 1971. [Includes a discussion on the nature of early medieval

cemeteries and churches, including the circularity of churchyards]

W J Watson The Celtic Placenames of

Scotland, originally published 1926 reprinted Birlinn, Edinburgh, 1986. |