|

From “Scotland and Scotsmen in the

Eighteenth Century’ by John Murray of Ochtertyre

Duke James

‘As the lines of Alexander Robertson of

Strowan’s character and fortune were strongly marked, some account of him

will not be unacceptable (Footnote In the summer of 1770, I was at the

goat-whey in Rannoch, while the memory of Strowan was fresh, and a number

of his companions, high and low, still alive who loved to talk of him.) He

was a cavalier in the purest sense of the word, having engaged in every

rebellion that took place between 1689 and 1746.. Having been attainted

soon after the Revolution, he served for some time in the French army; and

being a man of spirit and address, was all along well received at the

Court of St Germains, which was then filled with Scottish and English

persons of fashion.

Soon after the accession of Queen Anne

he received a pardon, for which he cared so little that he did not suffer

it to pass the Seals. During that reign he lived more in the world than

Highland chieftains usually do; and his wit, joined to his handsome person

and courtly manners, made him generally acceptable. His accession to the

Rebellion in 1715 did not make him worse, as he had slighted the Queen’s

pardon for his treason in King William’s time. After ten years

uncomfortable exile, the Earl of Portmore, who was his relation, procured

him leave to return home, from George I. That Prince had already given a

grant of the rents of the estate of Strowan to his sister Mrs Margaret,

for behoof of him and his creditors, who were not the less numerous for

his politics.

Upon returning to Rannoch he took the

estate entirely into his own management, turning his sister out of

possession, and treating her in a manner no less unnatural than illegal

(footnote. He first imprisoned her in a small island at the head of Loch

Rannoch, on which there was no house; then he sent her to the Western

Isles, where she died in misery. His companions said in his defence that

she was both an imperious and a wretched woman, which surely did not mend

matters. Even vice cannot be punished but by the magistrates. There was

certainly something peculiar in the blood of that generation. When Strowan

was pressed to marry, he used to say that nothing descended of his mother

could prosper. She was the daughter of General Baillie, of whom it was

alleged that, in order to ensure the succession, she had an active hand in

starving her own brother. It is a tradition of Rannoch, that as often as

she went abroad to ride or walk the crows followed after her in great

numbers making a hideous croaking, as if upbraiding her with her guilt).

Struan

But he soon found his situation ill

suited to a man of high spirit who had been educated in courts and camps.

Had his estate been much greater and entirely free, it would not have

sufficed a person of his romantic thoughtless cast, that wished to act the

part of both a chieftain and a man of fashion. Ere long he found himself

bested with difficulties which he was utterly unable to remove; and his

distinction between debts of honour and legal debts did not raise his

character or credit. (Footnote. If his creditors trusted to his honour, he

was most anxious to pay them but bonds or bills, he thought no more of the

matter. ‘Oh,’ said he, ‘that a man has security in my estate; let him make

the most of it.’. A messenger more fearless than the rest broke through

and apprehended him in his garden at Carie. So far from resistance, he

treated the man with great hospitality; but the women in the neighbourhood

tore an seized the catchpole, spite of all Strowan could say, and

stripping him stark naked, kept him under the spout of a mill wheel till

the poor creature was almost killed with cold. For this the chieftain was

tried at Perth, but acquitted through want of evidence. The room in which

Strowan slept and entertained company at Carie was the factor’s kitchen in

1770. In the garden, which had once had a good wall, besides fruit trees,

might be spied mint, rhubarb, and flowers in their natural state,

monuments of their former master’s taste and attention).

For a number of years the poor man was

beset with officers of justice who wished to imprison him; and though he

placed guards at the principal passes into his country to give him notice,

they sometimes put him in great hazard. This banished him for a great

while from Edinburgh where he was much in request; nor was it safe to

visit his fashionable friends in the low country. Even in circumstances

which would have depressed any other man he kept up the post and dignity

of a chieftain, which he could the easier do that he was exceedingly

beloved by his numerous clan.

He lived constantly in thatched houses

of one storey, the family ones having been burnt in times of war. At a

time when his great neighbours at Dunkeld and Taymouth had no notion of

pleasure ground or gardening, he planned, and in part executed a villa at

Mount Alexander with much taste and judgement, being picturesque even when

deserted and overrun with bushes and weeds. And his garden at Carie was

one of the best in the country and planted with good trees, both for shade

and fruit. Between these two places he divided his time as the fancy

struck him; and it was but four miles betwixt them.

In the year 1745, when seventy five

years of age, and in no condition to undergo the fatigues of a campaign he

joined his prince at the head of a considerable body of men. By doing so,

he said he would show the Elector of Hanover that, although he might give

his estate to that puppy Duncan Robertson, none but himself should raise

the clan. (Note. In 1745 George II ordered the Barons to report whether

the investiture of the estate of Strowan should be given to the heir male

or the heir at law. To the great indignation of the chief, they reported

in favour of Duncan Robertson of Drumachuine, who immediately after joined

the rebels, not very wisely.

In marching south Strowan lodged with

Mr Simpson, minister of Dunblane, a worthy, pleasant man. Being in

antipodes in politics, much good-humoured irony passed between them. On

the chief’s return, in Cope’s chain and arrayed in his furs, Mr Simpson

met him on the bridge. ‘Strowan’ said the latter, ‘you come back in better

order than you went.’ Oh,’ replied the wit. ‘all the effects of your good

prayers, Mr Simpson.’ After the battle of Preston, he was allowed to go

home, having got for his share of the spoils Sir John Cope’s chain and

furred night gown. Though he lived for several years after, Government

connived at his drawing the rents, whilst prudence taught him the

propriety of keeping out of the way of the military parties that were

stationed in the neighbourhood.

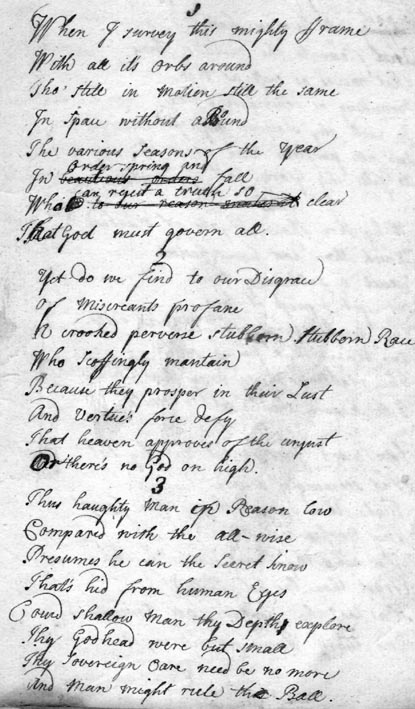

When he first became a proficient poet

cannot be now known. The probability is that he contented himself with

short effusions suited to the moment till poetic fame became the object of

men’s ambition. But at whatever time he turned his thoughts that way,

nothing could have prevented him rising above mediocrity but want of

application and distraction of mind, occasioned by his misfortunes and

straits. A moderate degree of cultivation, and the counsels of literary

friends, would have lopped away his luxuriance and corrected his

inaccuracies. Cruelly as his memory was treated in publishing, after his

death, pieces that were either unfinished or unworthy of him, his ‘Holy

Ode’ and ‘Farewell to Mount Alexander’, bespeak an elevated, well attuned

mind, capable in happier circumstances, of having soared still higher.

Considering the mean company he kept for more than twenty years, and the

strange life he led, the wonder is how he could exert his mental powers to

such good purpose as he did.

MS

(Note. James Moray of Abercairny told

me that between 1720 and 1730 he used to go over and stay a week with

Strowan, who was his relation, and always very kind to him. Nothing he

said could be more brilliant and delightful than that gentleman’s wit, or

more pertinent than his remarks upon men and things. But the pleasure of

his guests was diminished by the style of dissipation in which he lived.

In the morning his common potation was whisky and honey, and when inclined

to take what he termed a meridian, brandy and sugar were called for. These

were the liquors which he generally used, not being able to afford wines,

and perhaps liking spirits better.

When his guests declined the beverage,

he would say good naturedly, ‘If you be not for it, I am.’ Besides taking

too much of these cordials, he exhausted his spirit by lively talk; on

these occasions he would turn into his bed, which stood in the room where

he ate and drank. After sobering himself with a nap, he got up and walked

abroad, till he had recourse again to his cups. One day while Strowan was

asleep, Abercairny spied on top of the bed a bundle of papers, quoted on

the back like a law process. Taking it down he found a collection of his

host’s poetry, strangely assorted - here a serious one, and next to it an

obscene or satirical one). When half seas over (long his favourite

luxury), he often gave vent to poetical sallies which were not always

dictated by decency and discretion. Whilst their author thought little

more of them, and could not be prevailed upon to touch or chasten them,

his myrmidons, who flattered his vanity by extravagant praise, took

copies, which were circulated over the country.

In spite of his many failings, and the

bad company kept for a number of years by this extraordinary man, there

was a dignity and courtesy in his manner which, joined to the vigour and

sprightliness of his understanding, made his conversation highly

acceptable to persons of every rank. As he was exceedingly popular in his

own country, none knew better how to make his competitors keep their

distance (Note. There was then in his neighbourhood a laird who, without

sense or learning had the knack of versifying in Latin and English. As he

was a very absurd old man, it may well be imagined he would not be less

quarrelsome over his cups while a youth. On those occasions, after he had

reprehended his neighbours, Strowan called with much gravity for his page,

whom he directed to chastise that rude noisy fellow.)

Till the rebellion, he was a welcome

guest in the first families. (Note. None fonder of a visit from Strowan

than James, Duke of Athole, whose social hours were joyous and dignified;

who lived with his vassals like a parent and a companion. It had been the

custom for every gentleman to kiss the Duchess. He learned from her woman

that one of Strowan’s companions (afterwards an officer in the French

service) had once been his menial servant. On her complaining of having to

salute such a man, the Duke archly answered ‘madam, my friend is a greater

man than the king, for he can both make and unmake a gentleman when he

pleases.’) of the country, even when his dress and equipage did not seem

to correspond with the loftiness of his pretensions. On these occasions,

however, he took care to be attended by the gentlemen of his clan, and a

number of domestics, of a very different cast from the powdered lackeys in

the houses of the great, each of them having infirmities peculiar to

themselves. (Note. In his time Rannoch was the seat of numerous and daring

gangs of thieves. As they bade defiance to the government, it was not in

Strowan’s power to repress them, though he abominated their courses. Being

told of a great thief on his estate, he said he would try his honesty,

affecting not to believe the charge, whereupon he dispatched him to Perth

for a sixpence loaf, which the man did with great dispatch, bringing with

him a roll, which was then given into the bargain. As he might have

concealed it, Strowan would never after hear anything wrong of a man of so

much honour.)

It may be thought too much has been

said of this gentleman’s private life, but the abuse and abasement of his

brilliant talents show the inexpedience and danger of going much beyond

one’s depth, either in politics or expense (Note. It is to be feared that

the acquaintance of the present generation with the results of Strowan’s

muse is limited to the couplet quoted by the Baron of Bradwardine - ‘For

cruel love has garter’d low my leg. And clad my hurdies in a philabeg’

which the Baron pronounces an elegant rendering of Virgil’s ‘Nunc insanus

amor duri adversos detinet hostes’

Yet Strowan was unquestionably a man

of mark in Scottish literary society, and a personal friend of most of the

poets of his day, especially of the Jacobite Meston.

William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh

and London. 1888 |