|

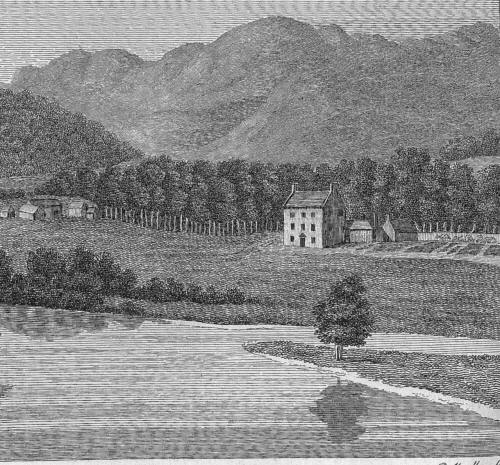

The House

that George built

An account in

last years Annual described how the Jacobite George Robertson of

Faskally escaped capture in 1746 by hiding in an oak tree near the modern

village of Pitlochry. Several versions of the story have ended with his

disappearance abroad and subsequent early death. But this was not so. He

lived for another thirty years and his doings are recorded in letters

preserved in an Edinburgh library.

George’s

father stated in a declaration made in 1712 that he was descended from

Alexander second son of Alexander Robertson of Struan and his second wife

Elizabeth Stewart daughter of John earl of Atholl who were married soon

after 1500. By a charter confirmed by the crown in 1533 the younger

Alexander and his wife Isobel Hay of Errol received lands which formed

the basis of the estate, and later barony, of Faskally. These lands did

not cover one continuous stretch of country but fell into two sections -

one extending some three miles up the left bank of the river Garry from

Bruar and a short distance down the right bank from Kindrochet to

Pitaldonich. There was then a gap (owned by Robertson of Lude) to the

river Girnaig and the other section covered the right bank of the Garry /Tummel

both north and south of the pass of Killiecrankie - the northern part

which included the main house being called Faskally and the southern part

Dysart.

In 1717

George’s father Alexander married Anne Mackenzie a member of a

distinguished legal family originally from Ross-shire. Her father John was

an advocate (barrister) and principal clerk of session in Edinburgh while

three of her brothers were also lawyers - Kenneth, an advocate and later

professor of Scots law at Edinburgh University, George also an advocate,

whose career will be noticed later, and John, a writer to the signet

(solicitor) in Edinburgh - all of whom had considerable influence on her

son at one time or another, and from whose correspondence the story is

told. Alexander died in 1732 leaving six daughters and an only son George,

then six years old. In his will he appointed Kenneth Mackenzie and a

county neighbour James Stewart of Clunes as curators for his young heir,

and by what was to prove a very fortunate step, they executed a formal

deed of factory appointing Anne to look after the estate on her son’s

behalf.

When he

was about 17 George was apprenticed to his uncle John Mackenzie but did

not take to the law and in early 1745, much to his mother’s dismay, was

considering joining the British army to fight in Europe. But he did not

go and a few months later war came nearer home. Like many families

George’s relatives were divided between Jacobite and government

supporters. The Robertsons under old Struan were mainly Jacobite but his

mother’s Mackenzies were mostly for the government though she had a

Jacobite brother and cousin. George Mackenzie, her older half brother, had

been attainted for taking part (detail unknown) in the ‘15, spent some

years as a wine merchant in Bordeaux and been pardoned in 1725, just in

time to stand as godfather to young George Robertson, while her cousin

John Hay, also a lawyer, was to come out in the ‘45. and go in to exile

with Prince Charles Edward remaining in his household in Rome for a

further 30 years. Young George joined the Jacobite army to serve in the

3rd battalion of the Atholl Brigade. His own part in the rising is not

recorded but the brigade under Lord George Murray went through the whole

campaign.

Like so

many Jacobite fugitives George disappears from record for some 16 months

after his tree climbing act. He was one of those excluded by name from the

act of indemnity but his estate was not one of those forfeited to the

crown, as Struan was, probably because of the old deed of factory and his

mother remained at home looking after it. As early as July 1746 Anne had

been wondering what she could do to help her son and George Mackenzie

advised her to ‘let the firey edge wear off’ before aproaching her

government supporting family and friends, among the latter being

apparently General Wade. George may well have gone abroad then but with

nothing said, his mothers letters to her brother John leave an impression

that they both knew where he was and may even have been in touch with

him. In November 1747 she begins to refer to ‘my friend’ who has been on

a journey and saying that she is glad to know that he is ‘out of the way

he had been in for some time past’. This was a reference to young George

who had just arrived in Trumpington near Cambridge, the home of his uncle

George Mackenzie, from where under an assumed name he wrote to his mother

that he was learning the French language which suggests that if he had

been living abroad it was certainly not in France but was perhaps

considering going there. Between January 1748 and June 1750 he was writing

from London still using false names such as James Smith and James

Mackenzie and trying to decide how to earn an independent living. It is

not clear when or if he received a formal pardon but in mid July 1750 Anne

was openly writing of her son and a legacy he was expecting and by

September he was back at Faskally signing a bond in his own name although

Anne was still acting as his factrix. A year later he was openly and on

his own behalf dealing with the factor for the (staunchly government

supporting) Atholl estate.

In

August 1756 George’s uncle Kenneth died, his place as advisor being taken

by his younger brother John with whom George kept up a fairly regular

correspondence as his mother had been doing for years. Later that same

year George met Jean Graham daughter of Patrick Graham a younger son of

the Inchbrakie family, and they were married in the following summer.

They

were to have no family but George, or perhaps it was Jean, soon decided

that they needed more living room. His father’s will showed that in 1732

there was furniture in the old house of Faskally in the dining room, the

Ladys’ room (clearly a sitting room), the blue room, the yellow room, and

the little room, all with beds and chairs and tables in them, in addition

to a nursery, garret and cellar with all the usual outbuildings such as

brewhouse, washinghouse, granary house, kitchen and stables. But in spite

of being deep in debt George decided to move down stream to the south of

the pass to what were the lands of Dysart and we can follow his progress

in unusual detail through the letters. In July 1761 he gave John Mackenzie

his reasons. ‘After weighing all the circumstances I am determined to

build at Dysart, by inlarging the dimensions a few feet of what I intended

here for a kitchen I can have a house as good as I could wish and much

more convenient than what I possess at present the roof of which is in so

crazy a way that in eight or ten years it will need to be renewed. As

materials are in the country at a moderate rate I am hopefull I will get a

house and what little office houses I will need for the first execute for

£300 at most. I would be greatly obliged to you if you would get from your

friend Mr Barclay a plan or two such as would suit me ... I make no doubt

of letting my farm here to advantage and settling my mother still more

conveniently than she is at present ... I will work 4 acres there easier

than one here .. will have neither Bog nor Rock to fight with and I have

plenty thorns to inclose with ... I have some few materials provided

already and I propose to employ what remains of the summer in laying in

more. .I promise myself .great pleasure in executing this scheme.’

John,

who had a country home not far away at Delvine north east of Perth,

replied a week later with encouragement and practical advice. ‘ Since

your heart and eye is in the Mortar Tub ... your first step is to resolve

on the fixt situation, catching all the advantage of Beauty or otherwise

the place affords, such as having a good spring easily commanded for the

use of the house, a dry stance and warm, never overflooded in winter and

the view of the cascade of Tummell or any other benefit the prospect

affords ... After your stance is determined fall to work directly and

gather materials - I mean stone, lime and timber and lay down the first

and 2nd in cairns and heaps on the place. I mean rough stone for very few

free stone must serve, in the leading of which and the timber and slate

you may possibly get some help from charitable friends and neighbours. The

collection of stones and lime I take to be the work enough for this season

... Next you are to ponder wisely on your Masons and Wright the first

you’ll find about Dunkeld ... early in Spring as the weather permit your

mason must fall to work’. John says that he and his wife propose to

drink ‘a dish of tea’ in the new house on 15 August 1763, the day after

the law term closes. He says he will work on the plan and will look after

the money for George and also that he thinks the present house will do for

George’s mother ‘with a little fresh straw on the kitchen’.

All

seemed set to begin but, although George reported in February that he had

workmen and horses ready, the first half of 1762 passed without progress

and in June George confessed that he couldn’t decide on the exact spot for

the stance and wished to consult John and his friend Harry Barclay, also

an advocate, but in that year appointed secretary to the Commissioners for

the Annexed Estates, the body that administered the estates forfeited by

the Jacobites. A month later George told his uncle: ‘I had the foundation

of my house staked out on Tuesday se’night and it is now almost digged -

tho’ I was slow to fix I am now quite well pleased with the stance. I have

the largest open Front that the ground would admitt of a gentle slope to

the east and west and two or three views of the water the bank of which on

one side is covered with wood to the north the ground rises gently for

about 150 yards and above that a fine bank of Oak. I have lime upon the

ground that will serve for this season and am busy leading stones and

propose to begin to build Monday se’night. I was in Rannoch last week and

bespoke all the great Timber for joisting and Roof all indeed that I will

need except two or three floors and Doors and Windows which must be of

foreign wood. I am at a loss how to get seasoned Oak for window cases for

tho’ we live in the midst of woods we have little Timber of that size and

none at all seasoned ... I have agreed with a very sufficient tradesman

for my wright.‘

But the

autumn found George still collecting material so that the house could go

ahead in the spring and the first half of 1763 saw some progress. By the

end of June he reported that the house was finished ‘as to masons’, the

roof begun and the kitchen walls to be finished in a few days and as much

plaster work as possible had been done before the frosts. But he did not

propose to do any more work that season. The ‘dish of tea’ had had to be

postponed and John upped the stakes by inquiring ‘when may we expect to

eat a leg of a chicken with your wife in her new house?’ The end of the

year evidently brought familiar problems with the tradesmen. Harry Barclay

who, in spite of a considerable workload in Edinburgh, seems to have

continued to take a practical interest in the project, wrote on 28th

December: ‘I do not wonder that you and the plaisterer shoud differ as to

the necessity of Cornishes [cornices]; because you are to pay them and he

is to be pay’d for them. But, for my own part, was he to give me his work

for Nothing I would certainly never introduce them into any Room under 12

feet high, when I think it is necessary you should have them. But there

may be great differences betwixt what is really Right in itself and what I

may judge to be so.’ He goes on to say that the window glass is ready for

collection and that he has ordered closet locks with handles as well as

locks.

There

was a setback in April 1764 when George reported that the house work was

at a stand owing to the weather and it was another year before he could

write in triumph: ‘Greatly to my satisfaction upon my coming here [to his

sister’s home at Urrard] I found my house quite dry and everything in

great forwardness about it after making allowances for the month of May. I

do not think this country I live in can afford a more agreable

habitation.’ Finally on 11th June 1765 he told his uncle John: ‘Yesterday

I took possession of the new fabrick ... I could not in idea form a notion

of anything more agreeable to me than the house and everything about it.’

The

other part of the plan failed as George’s mother was evidently not happy

with the renovation of the old house even with the fresh straw on the

kitchen. She and her sister Mary decided to settle in Dunkeld where she

remained until her death some eight years later.

In the

following years George continued to improve his new surroundings reporting

in March that ‘I have a cherry tree planted the beginning of February in

leaf and more Greens in my garden than his Grace’. Soon after this he sold

much of his estate to the duke of Atholl, presumably to settle some of his

debts, keeping only the house and a small farm. And at the new house at

Dysart, now called Faskally, George and Jean lived until they both died

between 1775 and 1777, leaving George’s nephew Charles Erskine Duncan of

Ardounie as heir to considerable debt still owing to John Mackenzie and

his great nephew and heir Alexander Muir. By May 1781, following a series

of complicated financial transactions, Henry Butter had acquired Faskally

and the two and a half centuries of the Robertsons of Faskally were over.

The house that George built was superseded by another in the nineteenth

century but the stance chosen with such care was admired by later visitors

including Queen Victoria, who was to call it ‘a very pretty place’, and in

spite, or even because, of the later extension of the loch, the place is

much photographed today.

Jean Munro |