|

Dr Nick Dixon and his

American-born wife Barrie Andriaan have an obsession. Some 25 years ago Nick

began his life’s work in exploring the crannogs - in fact one in particular

- in Loch Tay. Since then he has uncovered a huge storehouse of artifacts

and information about an aspect of Highland heritage that was virtually

unknown. As a byproduct of his work, he and Barrie have also created one of

the country’s premier visitor attractions as a way to raise money to

continue their research.

Crannogs are artificial

islands set in the shallows of lochs, most surviving today as little more

than submerged boulder-mounds or islets topped by stands of trees. However,

these defensive homesteads figured prominently throughout Scotland's past as

flourishing waterborne communities that lasted for centuries and came to

play an important part in clan refuge and warfare. They were occupied as

early as the Neolithic period, some 5,000 years ago, until the 17th century

AD.

Most Scottish crannogs

appear to have consisted of a single thatched roundhouse, deliberately built

out in the water for protection from wild animals and invaders. Based on the

results of Nick’s underwater surveys and excavations, we now know that the

crannogs were built as free-standing timber pile-dwellings in the lochs of

woodland environments, and as circular or sub-circular stone buildings on

man-made or modified natural rocky islands in more barren environments.

There are many crannogs

in Ireland, one known example in Wales, but none in England. More than 400

are known in Scotland but, as there are more than 30,000 lochs in the

country, the total number is likely to run into thousands. In Loch Tay,

Perthshire, where Nick’s Scottish Trust for Underwater Archaeology has been

excavating periodically since 1980, there are 18. At one of these, the late

Bronze Age/early Iron Age site of Oakbank Crannog, waterlogging has made the

preservation of organic materials spectacular. Surviving structural remains

include the original pointed alder posts of the supporting platform, floor

timbers and hazel hurdles forming walls and partitions, as well as the posts

that once provided a walkway to the shore.

The finds from the site

paint an amazingly clear picture of the lifestyle of the crannog-dwellers in

the area, and increase our knowledge of this period in prehistory. Wooden

domestic utensils, finely woven cloth, beads, and even food and plant

remains have all been well preserved. We know that the crannog-dwellers kept

cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, and produced dairy products including

butter, which in one instance was found still adhering to a wooden dish

probably only discarded because it had split apart.

Most crannogs are

situated opposite good agricultural land, and the discovery of a wooden

cultivation implement at Oakbank Crannog, together with grain and pollen

evidence, indicates a local population of peaceful farmers. They grew a

range of cereal crops including spelt, an early form of wheat previously

thought imported by the Romans. These loch-dwellers also cultivated a taste

for parsley which is not indigenous to Scotland, and therefore perhaps

indicative of trade with people further south or on the Continent.

The crannog-dwellers

went to some trouble in search of the finer things in life. They

supplemented their diet with a range of nuts and berries including

hazelnuts, wild cherries and sloes, but they had to make an extra effort to

pick cloudberries, which only grow up on the mountains. They also made

special trips to higher ground to collect branches of pine to make tapers or

`fir candles'.

Every discovery brings

up more questions; and in an effort to address at least one unknown area,

Nick and his team have constructed as authentically as possible a full-size

crannog near Kenmore in the shallows of the south shore of Loch Tay. At the

Crannog Centre is an exhibition displaying some of the finds and a chance

for the visitor to actually try out some of the ancient technologies of the

people who lived there three thousand years ago.

Two crannogs have particular

associations with Clan Donnachaidh. In the north west corner of Loch Tummel,

there was a small, partly artificial island on which Stout Duncan ‘built a

strong house and a garden, which gave the name of Port-an-eilein, or the

Fort of the Island, to that place’ (Statistical Account [OSA] 1792)

In 1913 it was described

as being ’50 yds by 35 yds, standing in about 7' of water, but there is a

deep channel between it and the shore. Carefully-laid stones appear to rest

on trees.’ It was submerged in the post-war hydro-electric scheme but in the

early 1970s ‘was briefly exposed when the water level was lowered and Mrs

Torry (Port an Eilean Hotel, Loch Tummel) saw stone slabs which she thought

were steps, on the N edge of the island.

In 2004 Nick Dixon, as

part of a survey of Perthshire crannogs dived over the site and reported

‘The top of the site is now 3m under water and is covered with the stumps of

trees cut down before submergence. The remains are still very obvious of a

well-made flagstone floor with a path leading to a flight of steps that went

down to the loch bed, some 2m deeper. One of a number of upright timbers at

the bottom of the stairs was sampled and produced a date of 110±50 BP (AD

1840).

The other clan crannog

is Eilean nam Faoileag - the Island of Gulls - in Loch Rannoch which is now

topped by a 19th century tower folly. In a 1969 survey it was ‘a completely

stone built island now measuring 17.0m NS by 10.0m transversely. A

considerable part of the island lies beneath the surface of the Loch which

has been raised at least 6ft in the last 30 years. According to local

information the sand bank on which it is constructed sweeps round in a

gradual curve to meet the S shore and prior to the raising of the loch it

formed a causeway just below the water.’

In the words of the MS

first written by the Poet Chief ‘the King having defeated McDougall of Lorn

somewhere in the hills betwixt Rannoch & Breadalbane and taken McDougall

himself prisoner, committed him to Duncan’s care who conveyed him to the

island of Loch Rannoch. McDougall obtained some freedoms upon his parole,

but by an evasion of that parole grounded upon the ambiguity of the words in

which it was expressed in the Gaelic Language he made his escape.’ The date

for this incident is the early 1300s

During the survey of

2004, ‘A large oak timber, lying partly embedded under the stones on the E

side of the mound, and wood from lower down on the W side were sampled for

radiocarbon dating. The oak gave a date of 840±60 BP (AD 1110) and the lower

sample produced 660±50 BP (AD 1290)’. These are preliminary results but they

seem to place the crannog right in Stout Duncan’s time frame. It would be

pleasant to speculate that Duncan himself managed the construction of the

island.

References

Blundell, F O (1913 )

'Further notes on the

artificial islands in the Highland area',

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 47,

1912-13, 260,

OSA (1791-9 )

The statistical account of

Scotland, drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different

parishes,

Sinclair, J (Sir), Edinburgh,

Vol.2, 475-6,

http://rannocharchaeology.arts.gla.ac.uk/Background/History.htm

http://www.crannog.co.uk/

PIC

1. The Crannog on the south

side of Loch Tay near Kenmore

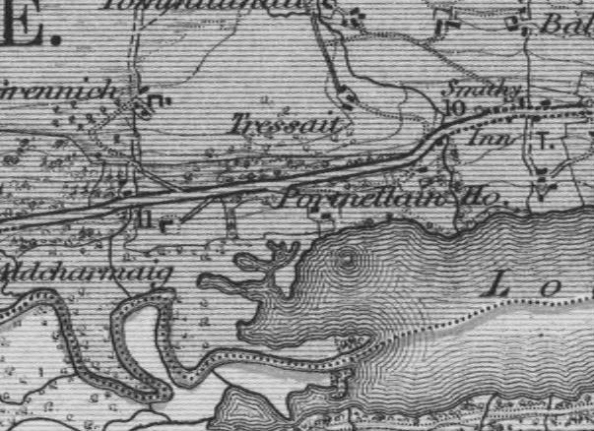

2 The disturbance in the NW

corner of Loch Tummel marks the site of Stout Duncan’s crannog stronghold.

3. Eilean nam Faoileag – the

Island of Gulls in Loch Rannoch. The gulls still nest here.

|