|

One of the most ancient of the great families of

Scotland, the clan Campbell, has given heroic men and great fighters to

our country from the earliest times.

Among the first of whom we read in old stories was Colin

Maol Maith, a name which means in English the bald, good Colin. This

great chief was highly honoured by Alexander the First of Scotland, who

gave him his niece in marriage, and made him Lord of the Isles and

Master of the King’s Household.

The king was once in the castle of Dunstaffnage with some

of his friends. The rebels in the Western Isles, hearing that he had but

a small following, came over secretly in their boats, thinking to take

him by surprise.

The alarm was given, and when the king looked from the

battlements of the castle, the sea all around was black with the boats

of the enemy.

“They have me now!’ said Alexander "there is no hope of

escape".

“My, liege/" said Colin Maol Maith, "disguise yourself as

a countryman and slip out of the castle. I will dress myself in your

Grace’s clothes, so that they will think you are still here, and we will

defend the castle until you reach a place of safety.”

Alexander was very unwilling to risk his friend’s life,

but his followers reminded him that the rebels would be able to do great

harm to the country if they had the king in their power. He consented at

last, and left the castle in a cowherd’s clothing, with one or two

friends in the same disguise.

Hardly was he out of sight when the islanders landed and

surrounded the castle. The defenders fought very bravely, but were

overpowered by force of numbers. With shouts of triumph the wild

islanders battered down the gates and rushed into the courtyard. They

seized Colin, thinking that they had the king in their power ; but when

they found out their mistake, they slew the valiant chief in their

anger.

All the defenders were put to the sword, but they did not

fall unavenged. The king reached a place of safety, and when he heard of

the fate of Colin he collected a large following and sailed for the

Western Isles. The rebels were defeated in a great battle, and all their

leaders were slain.

Colin (Callum) More, or the Great Colin, was t noted for

prowess while still a youth. He served his king valiantly, and was

knighted by Alexander the Third on the field of battle. The Western

Highlands are full of stories of his great deeds.

Colin fought on the king’s side against the rebellious

clan of the MacDougalls, whom he defeated in many battles. In a fight

with Ian Barach, or Lame John, chief of the clan, he won a great

victory, and pursuing the enemy too fiercely he became separated from

his followers. All by himself he forced a pass called Ath Dearg, or the

Red Ford, but was slain by the MacDougalls at Ballach-na-scringe, the

entrance into Gleninchur, on a spot still marked by a pile of stones

called Cairn Challum. The hero was buried at Kilchrennan on Lochaweside,

where his grave is still pointed out, and to this day the Duke of Argyll

is called The MacCallum More, or Son of the Great Colin.

Sir Niall, eldest son of Colin, was the first to be

called MacCallum More, after his father. He was a most valiant warrior,

and was created a knight banneret by Alexander the Third.

When Alexander died and Baliol consented to acknowledge

King Edward of England as overlord of Scotland, the pride of the

MacCallum More was touched. He took the side of the Bruce, and became

one of his most trusted friends, being called “the brother of the

Bruce.”

The chief of the MacFadyens came from Ireland with a

great following of Scots, Irish, and English, to help King Edward in the

conquest of Scotland. Landing in Cantyre he made his way to Lome, and

was joined by Ian MacDougall, whom Edward had made Lord of Lorne. They

might have overrun Scotland had it not been for Sir Niall, who gathered

together a small body of men and held the pass on the water of the Awe,

that runs out of Lochawe, while he sent a message to summon help from

Sir William Wallace.

Sir William was not slow in coming, and battle was given

in the Pass of Awe. MacFadyen and his men were defeated and routed, and

the chief escaped with a remnant of his following and hid himself in a

cave in the face of a rock. Wallace sent Sir Niall in pursuit of the

fugitives, and MacFadyen and his men were conquered and put to death.

After this Sir Niall became known as the Knight of Lochawe, and the cave

is called MacFadyen’s Cave to this day.

Meanwhile the MacDougalls had been defeated by Wallace,

and in the parliament held at Ardchattan Ian of Lorne was deprived of

his titles and his estate given to Duncan MacDougall for his fidelity to

the Bruce.

Niall Campbell followed his king through good and evil

fortune, and was one of the few loyal adherents present at the crowning

of the Bruce at Scone.

“Alas!” said the queen, the Bruce’s wife, after the

coronation, “we are but kings and queens of May, such as boys crown with

flowers and rushes in the summer sports!” The Scots were beaten at

Methven, and Bruce and his little court were compelled to take to the

heather. It was now Sir Niall’s turn to lurk among woods and caves in

company with Malcolm of Lennox, Sir James Douglas, and Gilbert Hay, his

friends and supporters of the Bruce. With their handful of followers the

king and queen wandered among the lochs and mountains, never remaining

long in one place, for the MacDougalls of Lorne were their foes, and

Edward’s men were hot upon their track.

Fleeing through barren glens, or crossing lochs and

rivers in leaky boats or by swimming, King Robert was always cheerful,

and kept up the spirit of the queen and his companions. He had one or

two books with him, and when the wanderers were resting in some cave or

around the evening fire he would read aloud stories of the siege of Troy

and the deeds of great men of long ago. Sometimes he would trust to his

memory, for he had read much, and recite tales from the old romances.

When the king was tired Sir Niall would take up the story

or some one would sing to the harp. It was summer-time, and the outdoor

life was a happy one in spite of danger. The men hunted, and shot deer

and hares with their bows and arrows ; and the ladies cooked the food,

and collected green boughs and heather to sleep upon.

Winter approached, and cold winds swept the leaves from

the trees. The king was obliged to send Queen Elizabeth and her ladies

to Kildrummie Castle in Ayrshire, his one place of strength. The castle

was taken; Nigel Bruce, the king’s brother, put to death as a traitor;

and the ladies handed over as prisoners to Edward.

In the following spring King Robert was once more in the

heather, in worse plight than before. Sir Niall accompanied him when he

was making his way from Tyndrum to Cantyre, pursued by the Lord of

Lorne. Still the king was full of hope, and kept up the hearts of his

men by telling them how Hannibal crossed the Alps in the time of the

Romans.

Sir Niall was sent to the coast to find ships for the

king. In stormy weather, with the rivers in full flood and snow still

blocking the passes, he forced his way through a country swarming with

enemies, and succeeded in obtaining boats for the Bruce’s little band of

followers. The king sailed for Cantyre, Sir John Menteith, the betrayer

of Wallace, at his heels ; and Sir Niall, with his friends Sir Gilbert

Hay and Sir Alexander Seton, bound themselves by a solemn oath “to

defend with their lives and fortunes the liberties of their country and

the rights of Robert Bruce their king against all mortals, French,

English, or Scots.”

The Knight of Lochawe commanded the loyal vassals who

were sent to Argyllshire to subdue the rebellious Lord of Lorne, the

Bruce’s greatest foe in Scotland. He was given the king’s sister,

Marjory Bruce, in marriage, and accompanied his sovereign in nearly

every battle, until the crowning victory of Bannockburn made his country

free.

The next noted Campbell was Sir Colin Oig, or the young

Colin, son of the brave Sir Niall; “he nothing derogated from the valour

and loyalty of his father.” As a stripling Sir Colin accompanied his

uncle King Robert to Ireland. While the Scottish army was marching

through a wood, Sir Richard de la Clare, King Edward’s commander, laid

an ambuscade to surprise the strangers. In order to draw the Bruce’s

soldiers into the wood he made some of his men leave their shelter and

shoot arrows at the Scots, hoping to provoke them into following, when

they would be surrounded and slain by the English.

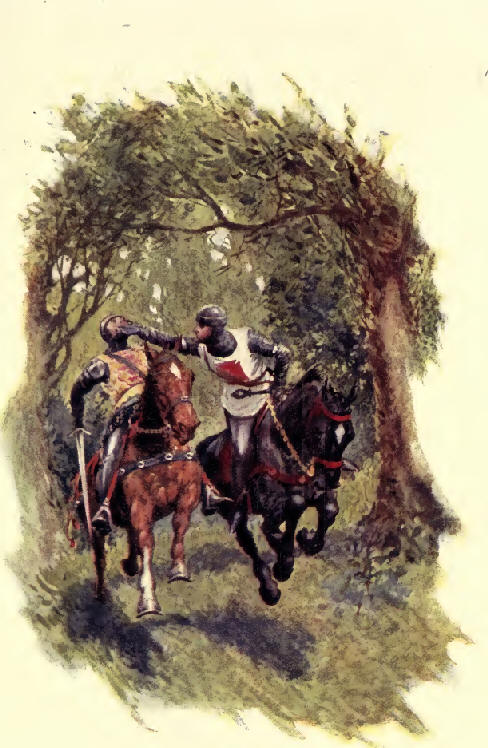

The Bruce, like an experienced warrior, suspecting an

ambush, forbade any man of the army to leave the ranks. Young Sir Colin,

however, becoming impatient at seeing two men boldly step forward and

defy the whole army, broke from the rest and galloped forward to fight

both the men. One he killed, and the other fled.

In spite of the youth’s bravery King Robert was very

angry at his disobedience. Riding quickly forward he seized his nephew's

rein and dealt him such a buffet that Colin nearly fell from his horse.

“Rash boy,” cried the Bruce, “knowest thou not that a

soldier's first duty is obedience? Come back to the army and show no

such bad example to my men!”

Colin was ashamed and sorry when his uncle led him to his

place, but he knew how to take a rebuke which he had deserved. He did

all he could to win his uncle’s approval, and became greatly

distinguished in the Bruce's wars. King Robert was pleased with him, and

when Ian of Lorne was driven out of the country the brave knight

received part of his land as a reward for his gallant behaviour.

When Robert the Bruce died his son David was but a child,

and the English invaded Scotland once more. Sir Colin remained faithful

to King David, and fought valiantly against the English.

“At that time none in Scotland, excepting children at

play, durst avow the Bruce to be king.” There were still some true men

left, however. The castle of Duntroon had been taken by the English, and

was under the guardianship of a false Scot, the Cumming. Robert Stewart

and Malcolm Fleming, lurking in Dumbarton, planned to surprise the

castle in the absence of the governor, and confided their plan to Sir

Colin. That gallant knight levied four hundred of his clan, and, with

Stewart and Fleming, stormed the castle and took it from the English.

Afterwards he won back the strong castle of Bute, and after a great deal

of fighting Scotland was free once more.

A noble and valiant knight was Sir Colin of Glenorchy. He

was a great traveller, having visited Rome three times, and was made a

Knight of Rhodes for taking part in the Crusades.

An old story tells that this Sir Colin had been seven

years fighting the Saracens in Palestine when one night he dreamed a

strange dream. When he awoke he was greatly troubled, for he could not

understand the meaning of the dream.

In the Christian host was a monk, who was reputed to be a

very wise man. Sir Colin consulted him, and the monk told the knight to

return at once to his native land, as a great trouble threatened him,

which only his presence could avert.

Sir Colin set out, and met with many adventures on the

way. Weary and footsore he at last reached home, and found that his

wife, the Lady Margaret, believed him to be dead. After long persuasion

she was just about to marry his neighbour, the Baron MacCorquodale, who

had told her that Sir Colin had fallen in the Crusades.

Sir Colin made a plan to prevent the marriage and find

out if his wife still loved him. On the day 2 of the wedding he appeared

under the walls of Kil-churn Castle disguised as a beggar.

The servants came and asked him what he wanted.

“To have my hunger satisfied and my thirst quenched,”

replied the seeming beggar.

They brought him food, which Sir Colin ate ; but he

refused to drink.

“I will drink only from the hand of the lady of the

house,” he said.

The servants mocked at his strange whim, but at last they

went and told their mistress that there was a strange beggar in the

courtyard, a dusty, sunburned fellow, who looked as though he had come a

long distance, and refused to drink save from her hands.

Wondering very much, the Lady Margaret thought she would

like to see the beggar. Bearing a cup of wine, she came into the

courtyard and offered the stranger a drink.

Sir Colin took the cup and drank the contents; then he

handed it back with a ring in it which his wife had once given him.

Greatly surprised the Lady Margaret looked at the ring

and then at the beggar, and in the tired sunburned face under the

pilgrim’s cowl she recognized her husband. She went to her servants and

told them their master had come home. They hastened to greet their lord,

and there was great rejoicing. As a punishment for the untruth he had

told, MacCorquodale was driven from the castle with all his fol- j lowing,

and after that day the Knight of Glenorchy and his lady lived happily to

the end of their lives.

The second Earl of Argyll was a faithful henchman of King

James the Fourth, who appointed him Lieutenant of the Isles and Governor

of the Castle of Tarbert. In this position he saw much fighting, and

rendered good service to the king. He imprisoned Donald Dhu, who called

himself Lord of the Isles, and would not obey his sovereign. Argyll

secured Donald in a strong castle, but the men of Glencoe rose and

released him.

Donald fled into the Macleods’ country, and was sheltered

by their chief. The king summoned Macleod to deliver up the rebel, and

on his refusal the chief was outlawed. The islanders rose in rebellion ;

and Argyll, Huntly, the chiefs of Appin, and the Maclans fought on the

king’s side. Bade-noch was ravaged by Donald, who took a terrible

vengeance upon his enemies of the clan Chattan. The rebels traitorously

sought help from England and Ireland ; and it was only after years of

fighting that Donald was taken prisoner by Argyll and confined in

Edinburgh Castle, where he lay for forty years.

After the capture of Donald, Argyll and Huntly were made

Lords of the Isles, which they ruled until the death of Argyll.

The earl was among those who tried to dissuade the king

from making war upon England. James was bent upon fighting, and Argyll

followed him into battle like a faithful subject. At Flodden he led the

right wing of the army with his brother-in-law the Earl of Lennox. Their

Highlanders, galled beyond endurance by the arrows of the English, broke

their ranks and rushed impetuously upon the foe, fighting like furies.

They were surrounded by an overwhelming number and cut down without

mercy.

Argyll and Lennox, deserted by their men, disdained to

flee, but held their ground like heroes, and were among the thirteen

Scottish earls who were found dead beside the body of their king. |