Alexander Murdoch

(1841-1891) - A Scottish Engineer, Poet, Author, Journalist

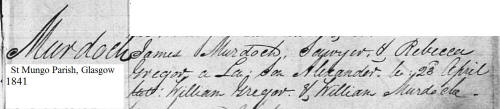

Alexander Murdoch was born in Taylor Street, St Mungo Parish, Glasow on

23rd of April 1841. It was only in later years that he added his

mother's surname, Gregor, as his middle name.

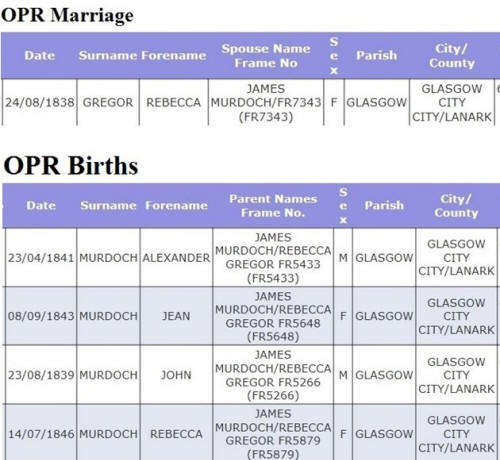

His parents were James

Murdoch (Sawyer) and Rebecca Gregor, who, in addition to Alexander in

1841, had a John in 1839, a Jean/Jane in 1843, and a Rebecca in 1846.

The 1841 Census taken on

the 6th of June, 1841, shows the then family of four in Taylor Street,

thus,

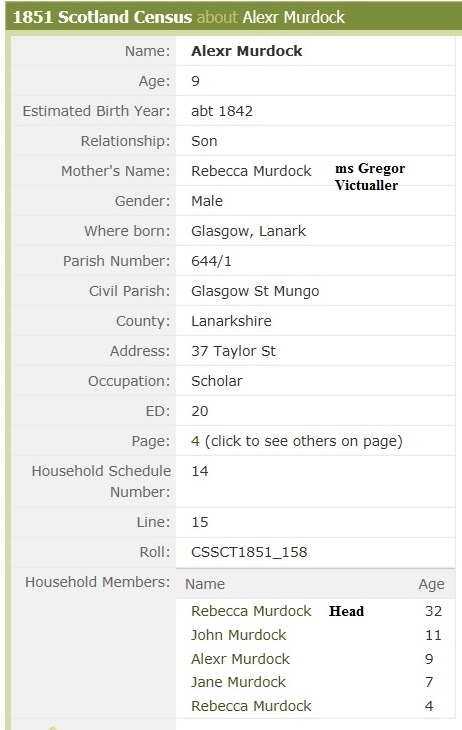

The 1851 Census for 37

Taylor Street, taken on the 30th March, 1851, shows Alexander as a

Scholar, his mother Rebecca, as Head of House, a Victualler to trade,

and her other three children. Her husband James is not listed, so had

possibly died between 1841 and 1851.

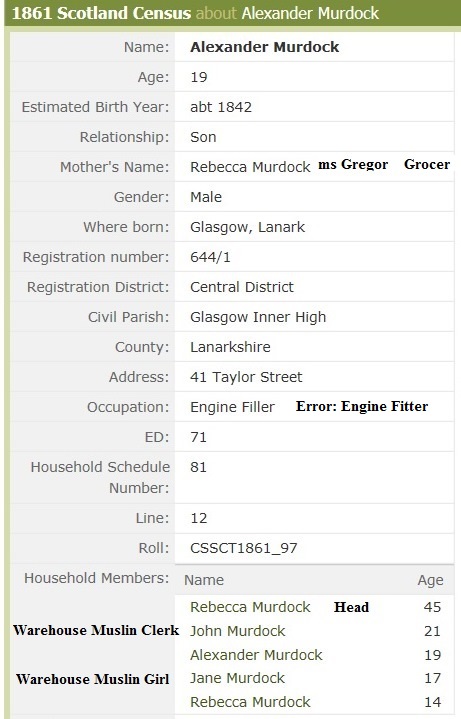

The 1861 Census for 41

Taylor Street, taken on the 7 April, 1861, shows Alexander as an Engine

Fitter, his mother as a Grocer, her son John as a Warehouse Muslin Clerk

and her daughter Jane as a Warehouse Muslin Girl.

In 1867, Alexander,

describing himself as a Journeyman Engine Fitter, married Marion Calton

in her home at 16 Hospital Street, Glasgow.

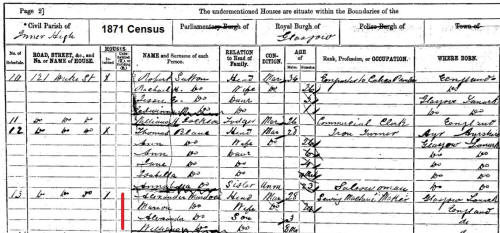

The 1871 Census for 121

Duke Street, Glasgow, taken on the 2nd of April, 1871 shows Alexander as

a Sewing Machine Maker (probably with the Singers Sewing Machine

Company) with his wife Marion and two children, Alexander Jnr., aged

three and William aged 8 months.

It appears that his

marriage and the births of another four children before the 1881 Census

on the 3rd of April, 1881, did not in any way hamper Alexander Snr.'s

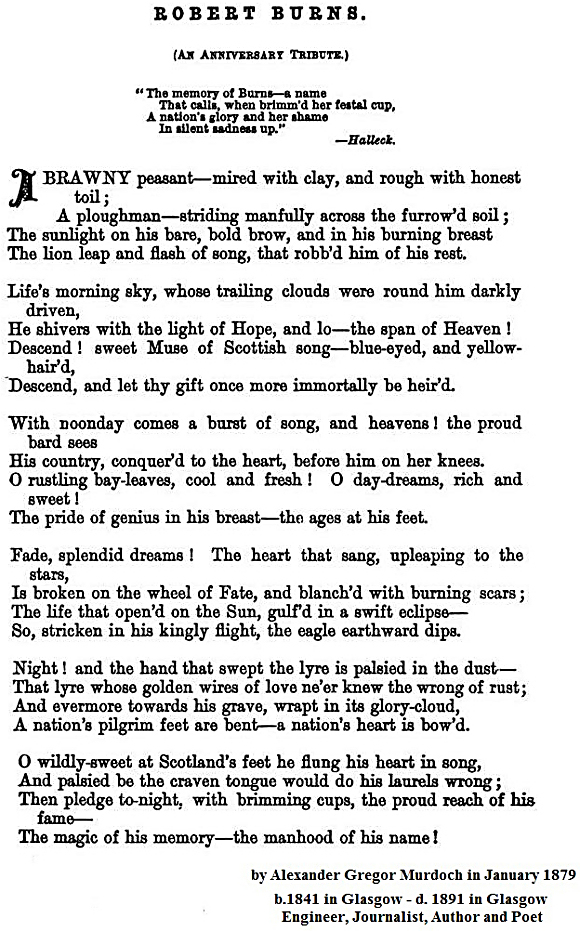

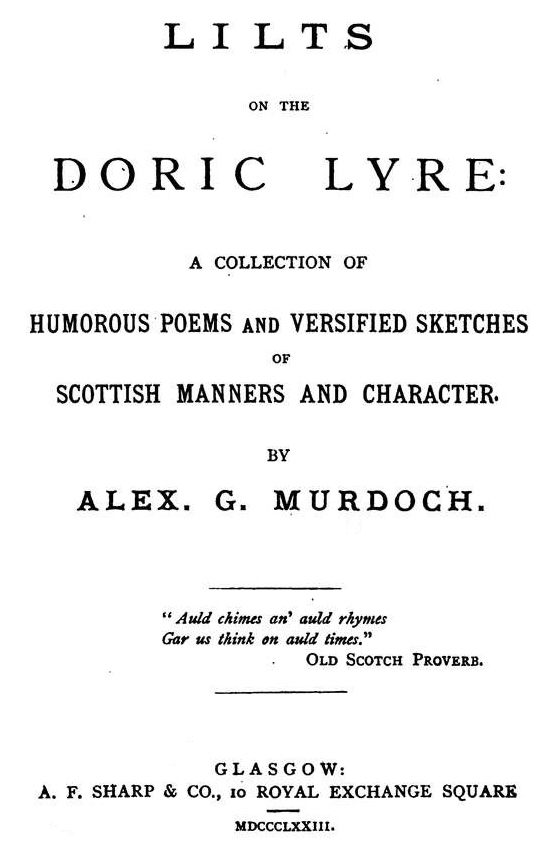

literary efforts and ambitions in the 1870s, for, not only did he

contribute many serious and humorous poems to the 'Glasgow Weekly Mail',

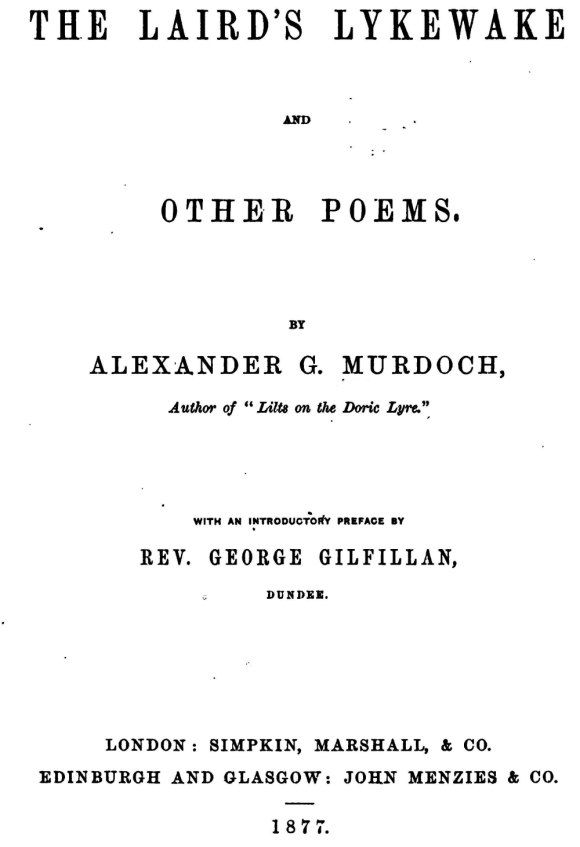

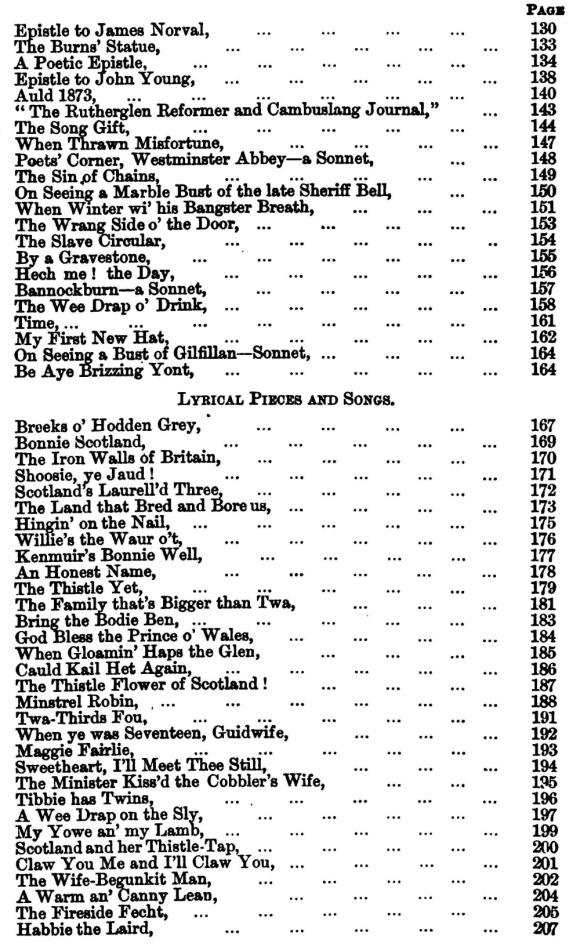

but also published two volumes of poetry, namely, 'Lilts On A Scottish

Lyre' in 1873 and 'The Laird's Lykewake and Other Poems' in 1877. Then

in 1879 he won the medal offered by the committee of the Burns Monument

at Kilmarnock for a poem on the Ayrshire Bard and afterwards accepted a

position on the staff of the 'Glasgow Weekly Mail'.

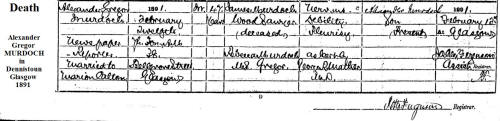

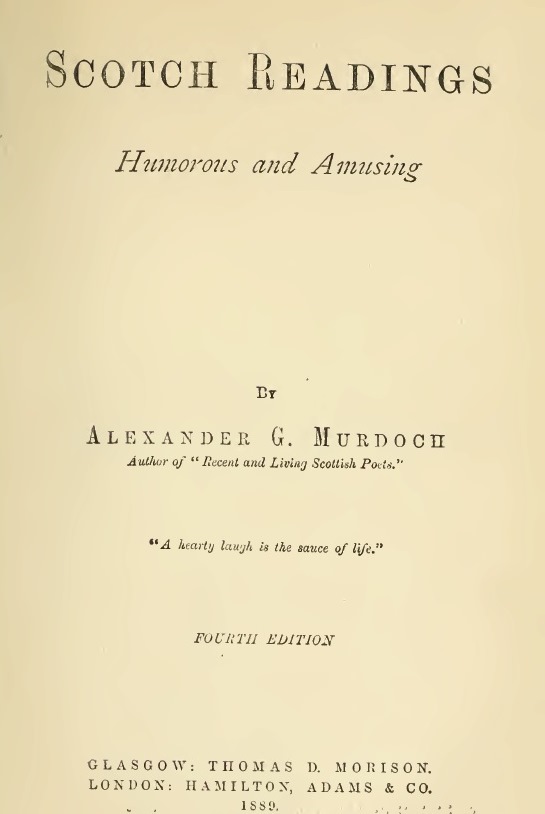

While with the 'Mail',

Alexander G. Murdoch, as he then styled himself, developed his prose

ability by writing several popular serial stories and then published at

least two more books, namely, 'Recent And Living Scottish Poets' in

1883, and 'Scotch Readings - Humorous And Amusing' in 1889. But sadly,

he died of Nervous Debility and Pleurisy at his home in 38 Bellgrove

Street, Glasgow, on the 12th February 1891.

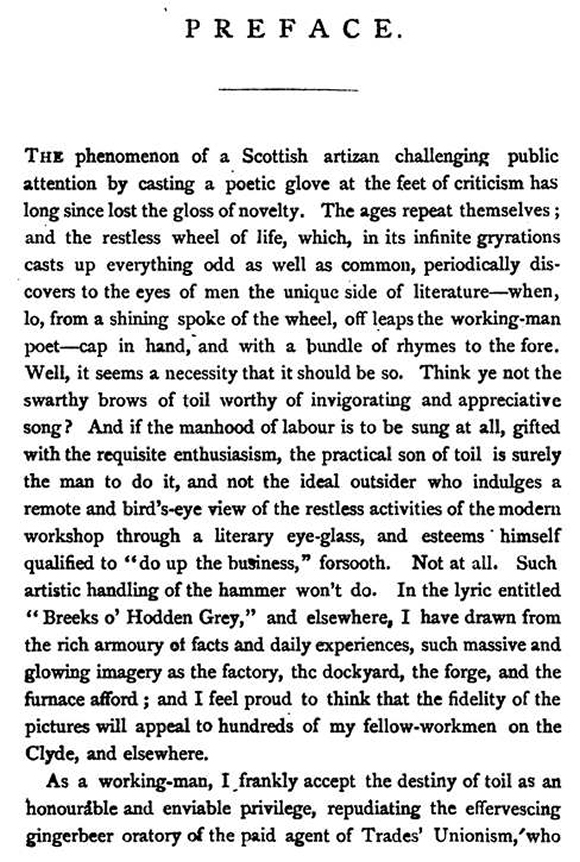

Mr Alexander Murdoch requests me to write a

few words of recommendatory Preface to his volume of Poems. This I do

with pleasure. He is one of our best recent recruits to the school of

Poets who went by the name of the “Whistlebinkie School,” many of whom

were real accessions to the list of our genuine Scottish Minstrels. Most

of them, indeed, might never have tuned their lyres at all but for

Burns, but still they were not slavish imitators of the Ayrshire Poet;

and, working in the same exhaustless mine of Scottish customs,

character, and scenery, they have brought out a great deal that is new

and valuable. The imitators of Pope found themselves in a vacuum—they

might have the style and even some of the genius, but they had no new

manners or phases of character to describe in England. It was used up

completely, and hence, while some degenerated into mere twaddle and

sound, Goldsmith, the best of them, had to go to Ireland, in his “Deserted Village,” and to the Continent, in his “Traveller,” in search

of new matter for his muse. But Scotland, till Bums arose,

“Lay like some unheard-of Isle

Ayont Magellan.”

Airid even after what he and Scott and Galt

and Wilson did for its discovery and disinterment, there remained a

great deal to do, and our Westland bards and Scottish novelists have not

even yet exhausted its rough and fineless riches.

A great deal of true Scottish raciness is to be found in Mr Murdoch’s

verses. The first poem which I remember perusing when it first appeared

is entitled the “Laird’s Lykewake,” and in part fulfils what had long

been a cherished ideal of ours—the poetry and interest of a Lykewake. We

remember well when that curious old Scottish custom was in full vogue,

and was observed in respectable as well as poor houses, and have been

present at one or two celebrations of it. There was a strange

combination of elements in its observance, which gave it a weird and

eery aspect, half ludicrous and half terrible. In a corner of the room

reposed the cold corpse of what had been perhaps the day before an

eminent preacher of the Gospel, who had died full of vigour, although at

his grand climacteric, of a very short and alarming illness ; or else of

some young and promising individual who had perished of a wasting

disease, with the salt on his breast, and a heart-heard whisper so

stilly low, which seemed to say, “ It is for ever.” In the centre of the

table, which stood in the middle of the room, stood a giant bottle of

smuggled whisky, flanked by oatcakes and a kebbock. Stationed around the

room were a variety of persons, young and old, grave and gay; here a

solemn elder quoting texts of Scripture, at first in a clear

unembarrassed tone, by-and-bye with a slight hiccup, as the aqua did its

office, and the morning light was approaching; and there a professed

jester—the jester of the village, a stocking-weaver to trade—with a

demure, hypocritical air in his waggish features, which by-and-bye,

under the same genial influence, warmed and waukened till his every word

was a quip, and his every sentence a droll story, and the room, the

bottle, the guests, and the bed on which the corpse was lying, shook

with unextinguishable laughter; and yonder a boy of thirteen, who,

between the sorrowful’ feelings awakened by the recent death and the

sight of his father’s body, and the ludicrous emotions started by the

strange stories, became a mere pendulum between a smile and tear, and

found his only relief in looking out, from time to time, on the night,

and seeing the Great Bear slowly lifting up his mighty stature toward

the zenith, and by-and-bye the first peep of the late October dawning

tinging the eastern horizon and unshadowing the northern mountains. It

was strange how the awe at first felt in the presence of a corpse, and

the superstitious dread of some lest demons should snatch it away, and

the love and sorrow for the departed, gradually yielded to the other

extreme of mirth, even as of all dinners that succeeding a funeral is

often the most redolent of laughter. Such a thing of shreds and patches,

of contradictions and sharp contrasts, is Human Nature, and such a

unique discovery of human nature was a “Scottish Lykewake.” Mr Murdoch’s

poem, the “Lyke-wake,” if not quite up to the mark of a subject worthy

of a Shakespeare or Burns, is a very clever production, and some of its

tales, besides being entertaining, contain touches of genius.

There is a spirited poem on “ Druinclog,” in the style of Macaulay’s “

Lays of the Boundheads.” Better than this is the “Midnight Forge,”

reminding us somewhat of Samuel Fergusson’s massive “ Forging of the

Anchor.” The following lines deserve quotation:—

“Bring out the molten monster, then, he's

ready, he's aglow.

And force his sides to battle with the steam god’s crushing blow ;

Hang on the cranes! heave out the chains! the white mass swings in air;

Heavens! what a scorching heat he casts, and what a blinding glare.

As white as seething foam he glows, and every bursting pore

Throbs with the fevered blood of fire, and spouts the molten gore.

O! in the sturdy olden days of foray and of fight,

When frequent in our Scottish hills arose the beacon light,

Had such another molten mass as this been lifted high,

Its gleaming terrors would have scared the white stars from the sky,

Flashed down a gray and angry glare on startled crag and lawn,

Disturbing the wild eagles’ sleep with dreams of early dawn;

Aroused the burgher of the town, the shepherd of the glen,

And put the sword-hilts in the grasp of roughly honeBt men.”

In his “Miscellaneous Poems and Sonnets” Mr

Murdoch seems to say, “Paullo majora canamas” These poems are in

English, and written with more effort and elaboration than his Scotch

verses. And such poems as “The Poet’s Mission,” “Behold the Man!” “John

Bunyan in Prison,” and his very striking strain entitled a “Hymn to the

Stars,” written at midnight in Glencoe, must be attractive to a class of

readers who may care less for his “Kirs’nen o’ the Bairn,” or “When ^the

Bairns are laid in Sleep.” It says much, however, for the versatility of

the Poet’s powers that he has written poems of nearly equal merit in

both languages, although we, for our part, prefer his English verses.

The first two stanzas of the “Hymn to the Stars” strike us as almost

sublime.

Very notable, also, are his poems of kindred purpose and power, entitled

“Robert Burns,” and the “Burns Statue,” which are sure to be read with

peculiar interest in this year of grace 1877, when the Glasgow working

men have done such honour to themselves and their city in erecting a

Statue to the Poet, contributed to in shillings, and where every

shilling implied self-sacrifice. These two poems we might quote, but the

book containing them is already in our readers’ hands, who will see in

Mr Murdoch’s strong chisel.

“A brawny peasant, mired with clay, and

rough with honest toil;

A ploughman striding manfully across the furrowed soil;

The sunlight on his bare bold brow, and in his heaving breast

The lion leap and flash of song that robbed him of his rest.”

In tenderer and more pathetic strains his

“By a Poet’s Grave” mourns over the fate of a hapless son of genius—the

late James Macfarlane, of whose collected poems we are glad to learn

that an edition has been promised by Mr H. Buchanan MThail, of Glasgow,

an early friend of the Poet’s, and in whose family lair the neglected

and unfortunate bard now sleeps.

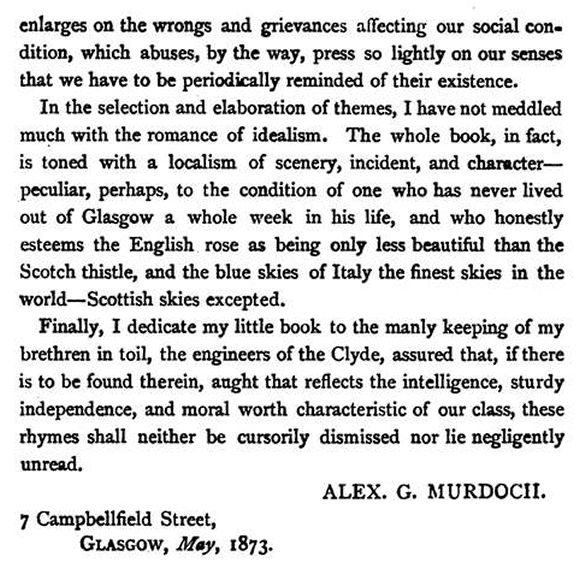

Had space permitted we might have mentioned as very good in a different

style the “Rent Day,” “That Bates a’,” “Blythe Johnny Maut,” “Plittin*

Day,” “The Hoose Takin*;” and in another style still "Expiation,” and

“Alpine, the King Slayer.” But our purpose is now accomplished in

recommending Mr Murdoch’s book as one of great and varied merit. It is

quite evident that the book has faults, and would be greatly improved by

a little more labor limce. But what gratifies us most about it is that

we think we see marks of distinct growth and advancement, and that the

Author is writing a great deal better since his first poems appeared,

and we entertain high hopes—on the condition of his writing better and

better still—as to his future career.

GEORGE GILFILLAN.

Dundee, 25th January 1877.

Download

'Lilts

On A Scottish Lyre' here (pdf)

Download "The

Laird's Lykewake" here (pdf)

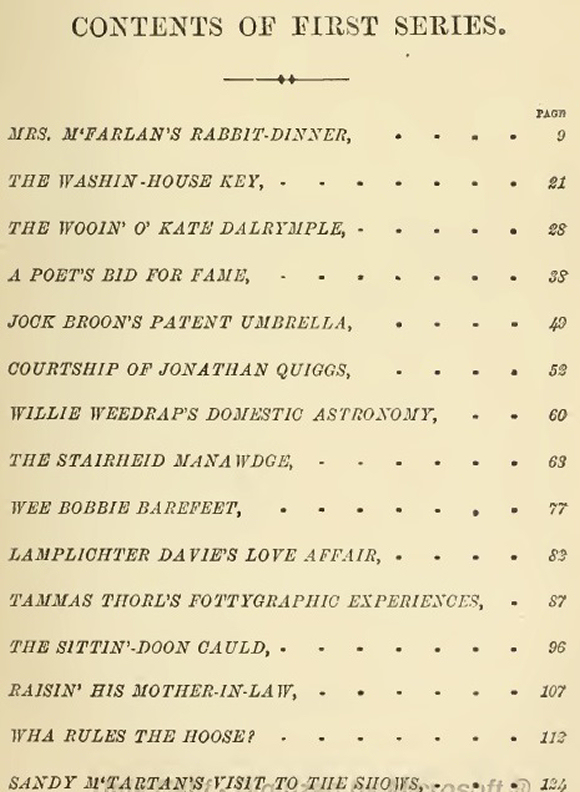

Mrs M'Farlan's Rabbit

Dinner

The Washin-House Key

The Wooin' O' Kate

Dalrymple

A Poet's Bid For Fame

Jock Broon's Patent

Umbrella

The Courtship of

Jonathan Quiggs

Willie Weedrap's

Domestic Astronomy

The Stairheid Manawdge

Wee Bobbie Barefeet

Lamplichter Davies

Love Affair

Tammas

Thorl's Fottygraphic Experiences

The Sittin'-Doon Cauld

Raisin' His Mother-In-Law

Wha

Rules The Hoose?

Sandy M'Tartan's

Visit to the Shows

Johnny Gowdy's Funny Ploy

The Mendin' O'

Johnny MacFarlan's Lum Hat

The Ministers Mistake

The Tailor Mak's The Man

Jock Turnips

Mither-In-law

Lodgings at Arran

Oor John's Patent Alarum

Mrs. MacFarlan

Gangs Doon The Water

Sandy M'Tartan's

Voyage to Govan

Robin Rigg and the

Minister

Johnny Safty's Second

Wife

The Gas Account Man

Davie Tosh's Hogmanay

Adventure

Gleska Mutton, 4d Per

Pound

Jean Tamson's Love

Hopesm and Fears

The Amateur Phrenologist

Peter Paterson, The Poet

Coming Hame Fou

The Bathing of the Stick

Leg

When is a Man Fou?

Washin' Jean's Comic

Marriage

Doon the Watter in

the Aulden Times

Tammy Gibb's Lan' O' Houses

Shirt

Washing in a Twopenny Lodging-House

How

Archie MacGregor Paid Out The Horse-Cowper

Tam Broon's Visit to

London

Geordie Shuttle Up The

Lum

Sandy MacDonald's

First-Foot