Recounting Blessings - My Father’s Tale

As

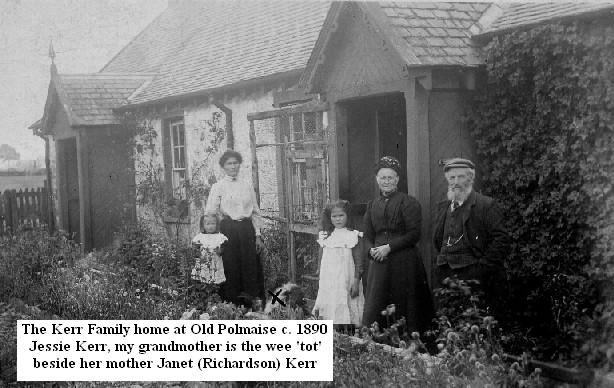

my grandfather John Henderson was growing up in the 1880s and 1890s

with one brother and two sisters in Newbigging, Newtyle, Forfarshire,

so my future grandmother Janet (Jessie) Kerr was being reared with

eight other siblings until the turn of the century in the Coachman’s

Lodge on the Cunningham Estate of Old Polmaise, Fallin in the

Bannockburn Parish of Stirling.

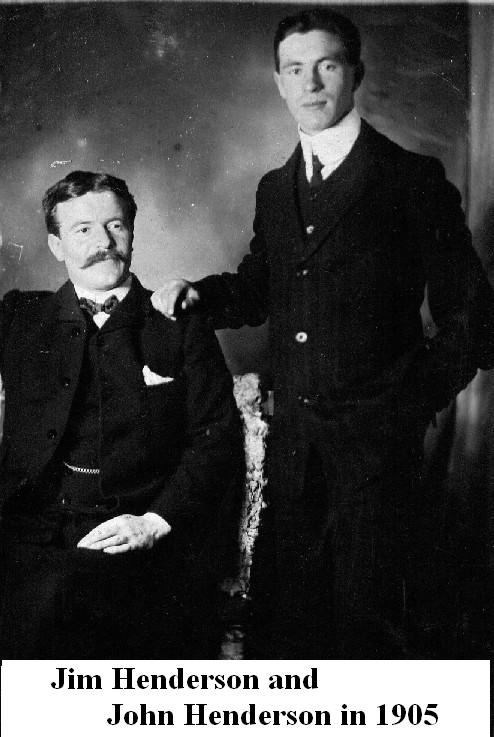

It is

probable that after the death of his mother Jessie Alexander Nicoll

Henderson in 1903 in Newbigging, and perhaps even before this, my

grandfather John Henderson, born in 1885 on the Couston Estate,

Newtyle, was, like his older brother James (Jim) Nicoll Henderson,

working on the railways of Perthshire and Forfarshire. Certainly,

according to the 1901 National Census, Jim Nicoll Henderson was living

in Kinbuck and working on the railway there in that year. His brother,

my grandfather John, I seem to recall hearing, started at Alyth

Junction, and this probably commenced around 1898/99. From the data on

a Certificate that I hold in my archives, 1898 was the year in which

John gained a Scotch Education Department Merit award at Lochee Liff

Road Public School in the burgh of Dundee.

However

the first clear awareness that I have of my grandfather John Henderson

as a working man comes from an inherited audio-tape that holds

reminiscences that my dad, James Nicoll Kerr (JNK) Henderson recorded

in 1982 at his home in 5 Victoria Park, Kilsyth. According to JNK,

his father John had been employed as a clerk at Dunblane Railway

Station, Perthshire in 1907, and that he had married Jessie in the

Kerr town family home at 18 Bruce Street, Stirling in the December of

that year.

JNK

tells his story :

"With

advancing years, and lowering horizons, it's a great comfort, and

ever-increasing source of wonder, to look back and count ones

blessings over these seventy odd years. I myself am no Cockney born

within hearing of London's Bow Bells, although the cathedral chimes

still toll beautifully in the Scottish city Dunblane where I was born.

Close by my birthplace, the river flowed over lovely waterfalls, in

sight and sound of which express trains thundered down the main line

to the South, chugged their way up to the tunnel leading to the North,

to say nothing of the local trains that lumbered past while others

were shunted amidst much clattering and rattling in the goods yard or

sidings.

1908 is

seventy four years ago and my father was a railwayman in these days

when the railway companies were four in number, all privately owned of

course - The Caledonian Company, The North British Company, The

Highland Company and The GWRE. My father was employed by The

Caledonian Company and in these days trade unions were in their

infancy and wages were anything but generous. A railway clerk dealt

with all kinds of traffic - passenger, freight, goods and parcels. He

worked a ten hour day, six days a week and had one week's holiday

leave, without pay, each year. Practically everything in these days

was conveyed by rail because there were so few lorries, no buses and

overall, traffic on the roads was very light.

Four

years later in 1912, having passed most of our time since 1908 living

in Doune, we moved to Stirling, taking up our residence at 4 William

Place in the Burghmuir area of the town. My early characteristics, as

commented on by my parents when we were living in Doune, didn't show

any great promise of true greatness in the future - unlike so many

opinions I heard about the countless mothers' darlings I dealt with in

my professional teaching life! According to my mother, I had lovely

hair and with hair like that I might have made a bonny girl.

Considering that I am a twin, and my twin, who died in infancy, was a

girl, perhaps there could have been some confusion! I am also told

that, as a three year old in Doune, I was sent across the Square to

the grocer's to buy a tin of Brasso, only to return in tears without

it. When asked why I hadn't brought it, I am quoted as having said,

'But Mum, I can't say Brasso!'

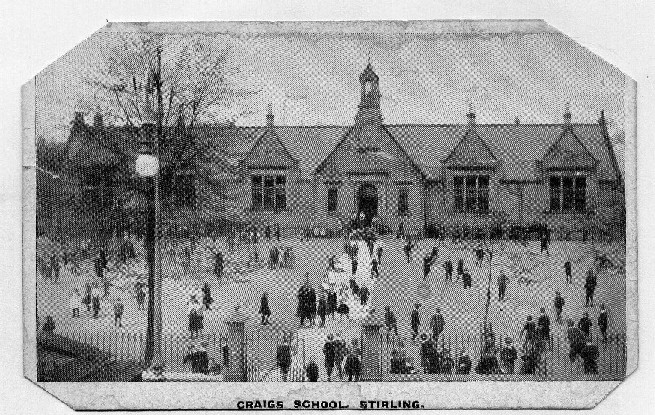

My

first school was the Craigs Primary School in George Street, Stirling

and my first teacher's name was a Miss Nisbet - all spinsters in these

days - while the Headmaster was a Mr Yule whose son had a chemist's

shop in the town for many years.

I went

to 'The Craigs' in the August of nineteen hundred and thirteen, just

one year before the First World War began, and three things stand out

in my mind concerning these times. First, I was smacked on my first

day at school for standing on a desk! Second, I was forbidden to

write with my left hand, the one I had always used naturally for that

purpose, and I was obliged to use my right hand instead! Third, there

was a medal in the class which the best scholar for the week wore

round his or her neck until it was won by someone else. My mother

declared that every time she renewed the ribbon with a lovely new one,

I always lost the medal. My chief rival for the honour week by week

was a Willie Brisbane, who lived in the same street, and whose two

clever sons became pupils of mine when I arrived in Cambusbarron much

later in my life as headmaster of the local primary school there in

1949.

This

particular sojourn in Stirling was short lived at this point as my

father soon received promotion to be railway stationmaster at

Longforgan in the Carse of Gowrie only five miles from Dundee. I spent

an ideal childhood in Longforgan, growing up in a truly rural

environment, learning so much of the lore of nature amongst the

fields, the trees, the flowers, the burn running into the silvery Tay

a quarter of a mile away, the birds, the poultry, animals of all

kinds, to say nothing of the elements in their seasons.

The

Great War must have been never very far from the front of my parents'

minds in these perilous years, but I was initially too young to be

conscious of the great tragedy of war. I can recall however some of

the rather exciting sides of things - for instance, my first sight of

a German Zeppelin trying to cripple the use of the Forth and Tay

Bridges as my father and I stood and watched from the station platform

railway bridge about midnight one night, listening for it and looking

towards Dundee in the distance, blacked out completely and looking

like a 'dead' town. The 'Alerts' could last for many hours, and trains

of any kind had to be stopped in their tracks and completely blacked

out until the 'All Clear' was again declared. I vividly remember my

mother making tea for dozens of passengers from a London to Dundee

train stopped in our station at four o'clock in the morning.

However

as my own years advanced, I did become aware of adult stress and

anguish and of the bereavement that prevailed over these four years.

But I can remember too that on the 11th of November 1918 every ship on

the Tay that had a hooter seemed to blow it throughout the whole day.

I can remember too that my mother was ill, very ill, with that 'flu

from which hundreds died in Scotland in that epidemic. I also remember

how people flocked to church services to express their relief and

thanksgiving. I can recall Rationing and Ration Books and the types of

food that were affected, including the so-called white bread! I can

also vaguely remember talk at school of 'U Boats'- and also of boys,

as well girls, knitting woollen scarves and sending them to the

trenches, enclosing cakes of soap and senders' names and addresses.

The feelings of sacrifice and doing without was heightened by the male

population being taken away from our village, as from so many others,

to what was called at that time 'Doing their bit'. I can remember our

Headmaster at Longforgan Primary School, Mr A.H. Finlay, being taken

away to serve - also clerks, porters, signalmen, postmen and others

were all called away.

Right

on the station platform were all the station offices - the General

Waiting Room, the First Class Waiting Room complete with running

water, wash-hand basins and toilet, the Gentleman's and further still

along the platform, the Goods Shed. There was also the familiar bridge

over the railway to take you to the platform on the southern side.

Behind all the platform buildings there was a grand courtyard where

the coaches, bikes etc. spilled their passengers or owners before they

approached the platform. Beyond all this was the goods siding with the

high loading bank and the complicated points system for changing the

wagons from one place to another. The Station House itself was a nobly

constructed seven room stone building, but with alas no cold water, no

hot water, no WC or bathroom, no gas or electricity but a big coal

range in the kitchen and paraffin lamps everywhere. All our washing

water was provided by an enormous rain barrel at the back door

supplied by a rone pipe from the roof of the house. Our other source

of supply of water for cooking and drinking came from a spring which

ran into the burn across the road, sometimes filling up very slowly

into the white enamel pail that we kept there for that purpose. The

burn was called the Pow and flowed into the Tay further down the

plain. For toilet facilities we would use the station Waiting Room -

First Class of course. When we had guests or relatives staying with

us for holidays the daily Timetable for trains stopping at the station

was always on display on the main corridor wall of our house. Indeed

many a time I had to 'run the cutter' to make sure the way was all

clear!

The

village was one and a half miles away from the station, up-hill and

all those who worked or wanted to shop in Dundee had to use the

frequent trains that ran from Perth to Dundee. I of course knew all

the drivers, the firemen and guards on the line and usually travelled

in the Guard's Van on my regular excursions for the day by day

messages to be purchased in Dundee - the Baker's, the Butcher's and

the Fishmongers, who also bought the fresh eggs that my mother

supplied each week - and Coopers the Grocer's - I can still see in my

mind's eye the delicious tins of Westfield Syrup that adorned Coopers

window display.

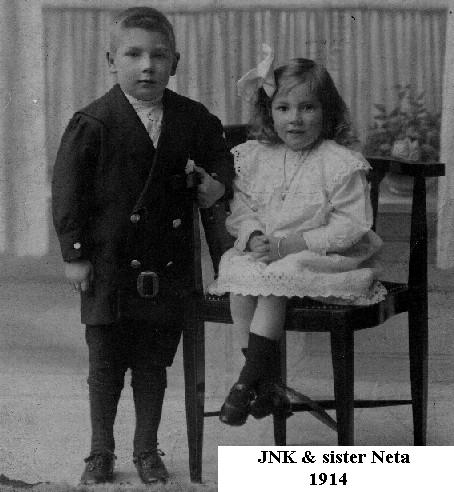

Along

with quite a variety of children from about our neighbourhood, my

sister Neta and I walked that mile and a half to school each day -

rain or shine or snow or frost or whatever, with our 'Coates of

Paisley' schoolbags of paper mache - presented by that firm to all

Scottish school children in those days - mine on my back and Neta's in

her hand, these bags contained all the books we needed, a big 'piece'

and a penny for a ticket for a bowl of soup at the school 'Soupy'. Of

course my piece was never big enough, but we survived. Somehow we

were content with simple things in these days and looking back we

seemed to have great times together despite the fact that we had no

school meals or any school buses.

Every

season brought its own diversions, games and pursuits - nowadays so

many of these things seem to be connected with money and expensive

toys - wireless far less radio or television were never parts of our

lives, giving us all the greater opportunity to do our own thing. As

boys we of course played 'bools' and the girls played at 'skippin',

while 'chessies' in season always had to provide a daily champion. We

boys played football too, but most often the ball was a tin can. What

a thrill it was to be taken to Dundee to La Scala Picture House once

in a while to see a film - silent of course -and the likes of Charlie

Chaplin. I remember buying my first War Certificate from a real army

tank which was on display in Dundee. We attended Sunday School in the

village presided over by the village postmaster. The Band of Hope

meeting on a Friday night used to be one of the highlights of the

week. To give you an idea of what was thought to be a modern invention

- to us, battery torches became all the rage then and a great

favourite in your stocking hung up for Santa Claus to fill. School

concerts were always a feature of the end of the school session. I,

myself remember reciting at eleven year old, 'He's no born yet', all

five verses of it! Then the Sunday School picnic was always a Saturday

afternoon in June, when we travelled in hay-carts to a suitable meadow

in another village some miles away, the carts decorated in bunting and

the children waving flags.

Being

war-time of course we had other things to think about and do as well.

This was a good excuse to employ children to gather in the potato

harvest. The custom was to close the rural schools for the whole month

of October. I joined my school pals to work daily in the fields from

seven in the morning until five o'clock at night for the handsome sum

of one shilling and sixpence per day. We had an hour off at lunch

which was invariably 'pieces and cheese'. It was back-breaking work

and at the end of a month's toil I was taken to Dundee to visit

Birrell's shoe-shop in the Overgate where I was able to buy a pair of

boots with my earnings. There were many sore bones and muscles at the

'tatties', but never a dull moment. We got to know the ploughmen and

the horses' names, sometimes getting to help to yoke them to the cart

that went up and down the drills after the digger to empty the creels

that we had filled with potatoes. We also used to get to help at the

mill - I can still feel the chaff tick, tick, tickling me down the

back of my neck - the harvest fields, the hay making, milking the cows

in the byre and slicing the turnips for the cattle; of course we also

liked chasing the rabbits disturbed by the binder as well as enjoying

many of the hundred and one other things that could be experienced

about a farm. Then of course there was no milk left on our doorstep

each morning. Instead we had to go to the farm and collect it in the

milk-can kept for that purpose and the milk often still warm from the

byre.

From

the village school at twelve year old I went on to the Harris Academy

in Dundee where for two years I learned to live and study and enjoy a

completely different environment - that of a large city and a large

school. Moreover I travelled the five miles there and back by train

every day - another new experience in its regularity. On the sporting

front, I not only showed promise as a footballer winning my way into

the Under 14 representative team for the whole of Dundee, but also

taught myself to swim in the lovely saltwater indoor pool down at the

docks. On the academic front I managed to do some studying in between

all my other recreations - enough indeed to pick up the second year

English, History and Geography prizes at the Academy! Then, at the end

of my second year at the Harris, Neta and I went on to Forfar Academy

due to our father being promoted to the post of Stationmaster at

Justinhaugh, a station between Forfar and Brechin. We thus travelled,

together this time, daily by train to the Academy for the next two

years.

There I

enjoyed school, but my lasting memories of that period in my life are

of joining the Tannadice Troop of Boy Scouts led by a young laird,

'Jock' Neish, who seemed to think of scouting, and practising scouting

as the guiding principle of his life. He, more than any other

person, shaped and influenced my teenage years, and I pay tribute to

him as a great Scout. He was very much in the mould of the late Sir

Ian Bolton (Bart.) and the late Major F. Crum, both of whom I was

proud to be associated with when my father brought the family back to

Stirling in 1923 and, in due course, a new home at 11 Abbotsford

Place, Riverside, and another new school, the High School of Stirling.

By that

time the Ten Scout Laws were woven into my system as a way of life and

it was only the cry, 'Come over into Macedonia and help us', from the

Holy Rude Church in Stirling, of which my father was an Elder, and I

had become a Sunday School teacher, that wooed me off to become the

Captain of a Boys' Brigade Company, thirty strong, in that Church.

The three Scoutmasters that I have mentioned, and the many other

magnetic personalities that I have met over the years, have

contributed greatly to the quality and enjoyment of a full life for

me. The kind of training I received has taught me, I hope, the true

meaning of sportsmanship, the ability to lose with grace and much more

besides. Then again, thanks mostly to the influence of my parents, I

have always chosen my friends carefully, but, besides these, I also

have also had plenty of acquaintances.

The

Loving Parents of JNK (b. 1908), Neta (b.1910), and Margot (b.1921)

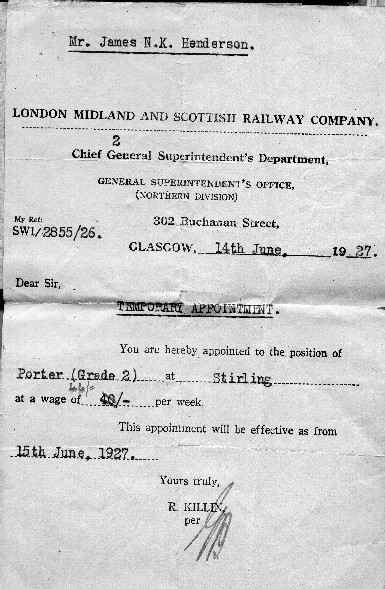

As a

teenager I was never deprived of the necessities of life but, on the

other hand, I was always encouraged to provide any extras by my own

efforts. For example, as a student during the long summer holidays, I

used to work an eight hour day as a Porter at Stirling Railway Station

for two pounds and six shillings per week.

At

other times, I picked berries at Blairgowrie, and, in the wintertime I

would tutor in the evenings for three shillings an hour, and of

course, such earnings certainly helped to augment our small family

income.

JNK

with the ‘hat’!

As you

can gather from these brief reminiscences from my early life, it is no

surprise really that I now look back in wonder at one long line of

helping hands, happy friendships and loyal comradeship, not

forgetting the many other supportive people along the way who guided

my development. Looking back it is clear to me now just how much more

I owed them than they owed me."

Recorded by JNK Henderson in 1982

I

continue the story:

As JNK

said in 1982, (at the end of this talk given to the PROBUS Club in

Kilsyth that year, spoken in his presence at the Club, but via a

tape-recorder due to his increasing physical infirmity and loss of

fluency in spontaneous speech) "I have said nothing of my professional

life this morning; after all I have covered only the first twenty odd

years of my life and, in the words of the Queen of Sheeba, I can say,

' the half has not been told' " !

As my

own developing memory really only started to hold impressions of our

family life from about 1943 onwards, and, as many memories one retains

of people and events tend to be very selective in nature, I cannot

possibly do full justice here to the other sixty-one years of the life

of JNK. But what I can do, is, to provide some snippets, that this

very modest father of mine perhaps only mentioned about the 1923 to

1941 period. All the foregoing was mostly learned about from listening

to his sister, my much loved Aunt Neta, my mother Nancy, and from

studying old photographs.

1923

- 1929

...... When the family returned to Stirling in 1923, JNK went to the

High School of Stirling, took his Highers in Class Five in 1925 and

then went straight on to the University of Glasgow to complete an MA

in English and Scottish History in 1928.

His

final degree exams at the University were onerous, not only

academically, but also for the mode of transport that he had to use to

get to Glasgow and the examination hall by 9.a.m. for his ‘Finals’ in

1928. The Strike that year meant that his 'Privileged Ticket' on the

non-running trains was useless and the buses were not running either.

So he had had to set off each day from 11 Abbotsford Place in the

Riverside, Stirling in the early hours of the morning on his bike,

call in at his Uncle Bob Kerr’s in Denny for a cup of tea, go on to

sit his two, three hour, papers in Glasgow, and thereafter pedal his

way wearily home to Stirling evening - always of course including

another welcome visit for cuppa in Denny on the way past!

The

following year he successfully completed teacher training in Primary

and Secondary school subjects at Jordanhill Training College, Glasgow,

and then was very fortunate to be given an immediate appointment as an

assistant teacher in Bridge of Allan Primary School.

Throughout these years, and for a few more thereafter, JNK (Jim or

Jimmy) Henderson excelled in local sport - as a Scottish Secondary

Juvenile Cup medallist with Vale of Bannock 'A' at left half-back, as

a left-handed batsman with Bridge of Allan Cricket Club, and as a

dashing wing three-quarter with Bridge of Allan Rugby Football Club.

JNK won

the hand of a colleague teacher at the High School of Stirling, Nancy

Telfer of Falkirk, and they married in Falkirk on the 15th August,

1934. I learned in later years that Jim and Nancy set up home in

1934/35 in a newly-built £300 ‘Headridge’ bungalow at 17 Easter

Cornton Road, Causewayhead. The bungalow was named 'Revoan' after a

particularly memorable week in JNK's life in 1932 while trekking in

the Cairngorms with his best man-to-be, Jim ‘JJ’ Walker.

Among

other things, this was the 'love-nest' for the arrival of Elizabeth

and myself!

The

heavy clay garden was a challenge to JNK's horticultural skills –

those no doubt inherited from his forebears in Newtyle and Leslie. The

'black-out' roads, down hill by unlit bicycle from top of the town

fire-watching to Causewayhead in the early days of the Second World

War were negotiated regularly without any major accidents - just!