1944-1949

Banknock Village – ‘Anyone for Tennis?’

The school

summer holidays in July 1946 took in a planned fortnight’s stay

in St. Andrews. I say ‘planned’ because it was foreshortened by

a ‘clothing focused’ burglary of Schoolhouse, Banknock while we

were away. The detectives later told us that, due to previous

war-time rationing restrictions on clothes, the Glasgow criminal

fraternity were busy supplying the black-market at the ‘Barrows’

on Glasgow Green with all apparel they could lay their hands on.

In the event, we were left with only the clothes we had taken

with us on holiday. Dad was worst hit because all his good suits

‘went west’ except for the ancient ‘plus-fours’ which he

often wore but others would only have deemed wearable on

a golf course a la Henry Cotton! Apart from being so

out-of-fashion, we were told that these baggy anachronisms would

have been too easily identified as stolen goods by police on the

look-out in the areas where the burglars’ fences operated in the

city.

However, all

these traumas apart, we had a great holiday, albeit shorter than

expected, in the city home of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club.

Playing the Old Course did not interest my dad, but the same

could not be said for our frequenting the lovely enclosed

‘Step-Rock salt water swimming pool arena with its nice wee

beach and paddling for us wee folks. Mornings tended to be spent

shopping and site-seeing, before we all played a daily game of

putting on the magnificently smooth, yet delightfully undulating

putting-greens near the West Sands prior to taking lunch in our

very comfortable guest-house opposite the West Port. Afternoons

were happily passed, swimming then shivering, paddling and

sand-castle building, picnicking and ice-creaming, at the

sheltered Step-Rock sun-trap.

Then one

evening my mum said that she wanted to go for a walk along to

Kinburn Park to see the tennis. The lure for my sister Elizabeth

and I to go along with this was the presence there of swings and

a shute. As it happenned, however, I was entranced by the game

called tennis that all these folks in beautiful ‘whites’ were

playing, and, as was my wont, I mentally decided that this would

be a game that I would love to try to play when I got back to

the village. I also knew that A.J. Mee’s Encyclopedia would no

doubt supply me with its rules and many other relevant facts as

well!

Our good

friend, a local contractor, John McLean, duly came east in his

big car to pick us up and whisk us home in the wake of the

‘break-in’ at the schoolhouse – incidentally, I first learned

about ‘double-declutching’ the car gear-box on that return

journey – but, apart from all the mess in the house left by the

burglars, an almost unbelievable co-incidence occurred when I

poked my head round the door of the cloak-room cum ‘glory hole’

walk-in cupboard under the schoolhouse stairs. There – before my

very eyes – as if saying, ‘pick us up and play with us’ - were

my parents’ two ancient tennis racquets, and from my Kinburn

Park experience, I immediately had a fair idea of to what use I

could put them!

So, as soon as

things got back to normal – with mutilated doors and broken

windows etc. repaired or replaced – I studied the encyclopedia,

found as many tennis or rubber balls as I could, and headed off

to the school playground with mum’s racquet to practise hitting

balls against any wall that seemed reasonably clear of windows.

The school had been built on a fair slope, so the gable walls in

the rear playground, rose about four feet higher off the ground

than those at the front street end. This meant that, unless I

was very rash, the two windows on the sand-stone wall where I

had chosen to experiment, might be relatively safe from harm.

Wishful thinking, yes, but they indeed survived many a near miss

in the rest of that summer, as well as in other years’ many,

many summer hours spent on forehand and backhand (less

controllable!) driving, lobbing and chipping against that wall.

As chalking

the stone walls of the school was totally forbidden, I was only

allowed to stone-scratch a few marks at the correct height to

indicate where a tennis net would reach – although this target

became more identifiable because of the building’s construction

comprising huge well pointed and indented stone blocks. This

chiselled indenting of the stone blocks of course made the

directions taken by rebounding balls less predictable, which,

while leading to a certain degree of frustration, also, as I

became more skilful, provided excellent preparation for dealing

with even the most inscrutable opponent’s returns in future

playing of the real game.

In addition

the playground was ‘multi-purpose’, as it housed two large

shelters for pupils to use in wet weather! Thus I could also

practise against their supporting walls in inclement weather,

albeit in a more limited fashion … until … because the balls

would become sodden from my quite often sclaffing them out

sideways into the wet playground, the gut strings of my mum’s

old racquet would burst and thus cause temporary deprivation

until repaired in Palmer’s sports shop in Port Street, Stirling.

Luckily we made the long journey to Stirling quite often by bus

to visit my Grandma Henderson, so the sports’ shop became an

attainable (essential in my eyes) port of call!

Meanwhile, the

idea of competitive tennis matches over a net became another

priority objective, especially when, I, as a very normal selfish

‘infant terrible’, knew that I would win, mainly because neither

my sister nor Robin, as prospective opponents, had practised as

hard as I had. However, first things first – ‘Bumpy Ibrox’ had

to be converted into a tennis court, and consequently some form

of barrier had to be manufactured as a tennis ‘net’. In the

event, strategically placed ‘bean-bags’ indicated where the

court ‘lines’ were – a first cause of many ‘out/in’ arguments in

later games. The second cause for umpteen debates came from the

improvised barrier in the middle of the court. What we invented

for this ‘net’ was merely a bit of mum’s spare clothes’ rope

stretched over and between two up-ended ‘orange-boxes’ weighted

down with bricks. (c.f. The boxes were obtained from the garden

as shown behind me in the photograph with the ‘cuv’ at my feet

in Chapter One). This time the disputes were of the, ‘yes it’s

over, no it’s under’ variety. Sad to say, in due course, for

more reasons than just mere squabbling about decisions,

competitive tennis was reluctantly abandoned. Why? Well, actual

tennis courts have high protective net fencing around their

peripheries. Unfortunately we had no such fencing. Indeed, worse

still, as additional hazards, we not only had a hay or corn

field at one end into which many a ball regularly disappeared

never to be seen again, but also there was an impenetrable

hawthorn hedge at the other end whose owners on its far side

soon proved to be extremely unwelcoming people to approach with

the request, ‘Can we please go down into your garden and get our

ball back’!

Although this

exciting competitive experiment was deemed another relative

failure, appetites for the game had been whetted, as witnessed

by the fact that both Elizabeth and I not only continued to

practise tennis against school walls in Banknock, and later in

Cambusbarron and Bannockburn, but also became club champions in

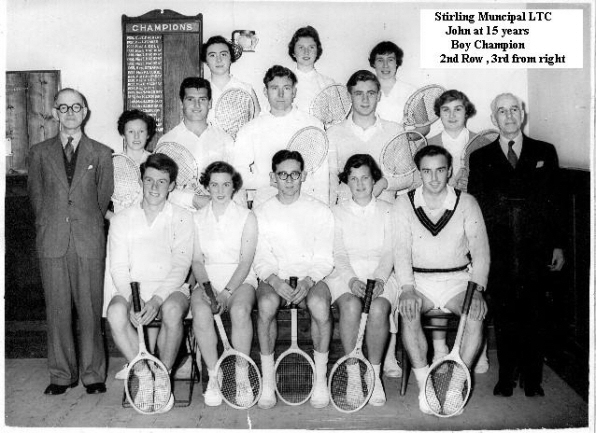

our teens at the Municipal LTC within the King’s Park, Stirling.