|

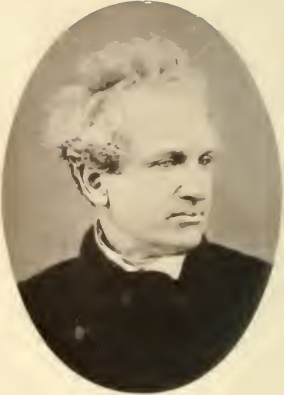

Thomas Aird, author of

the following Poems, was the son of James Aird and his wife, Isabella

Paisley, and was the second of nine children. He was born on the 28th of

August 1802, in the parish of Bowden, Roxburghshire, under the shadow of

the Eildon Hills, in the enchanted Border-land, close to the abbeys of

Dryburgh and Melrose, which the genius of Scott has made for ever

memorable. The Tweed, which he dearly loved, flows through the classic

vale, and from the rising ground you see upon the horizon the low blue

line of the Cheviot Hills and Flodden Field. The family of Aird belonged

for generations to that substantial and independent class named

Portioners, who cultivated their own land, held in feu of a neighbouring

nobleman, and who frequently combined with this some other industrial

employment. His parents, who professed the religious principles of the a

Antiburghers, were persons of admirable character and intelligence. They

brought up their children anxiously in the fear of God, and enforced a

careful, though somewhat strict observance of Sunday—

“Such as grave livers do

in Scotland use.”

Woe to the offender who

betook himself to whistling on that day, or to vain whittling with his

knife. Theirs was an orderly, yet happy home ; and on weekdays, when

lessons were over, the father would sing to the little circle some rare

old Scotch song, while the kind, thrifty mother plied the

spinning-wheel. It is said that a library containing some romances,

which Thomas started in Bowden when a lad, was at first regarded with

considerable suspicion by Mrs Aird. She was afraid of the seductive

literature, and thought, besides, that it was apt to interfere unduly

with the knitting and sewing of her daughters. But the good lady,

stumbling by accident one day among the books upon ‘ Thaddeus of Warsaw/

was so delighted with the tale, that not much more after that was said

about the sin of novel-reading. The venerable pair died each at the age

of 86, having spent sixty years together in married life; and their

gifted son never ceased to revere the memory of those whose holy

affection had guarded his youth from evil, and kept it pure. The

following domestic scene, in the pages of the ‘ Old Bachelor,’ is

evidently drawn from his father’s home : “To see the old men, on a

bright evening of the still Sabbath, in their light-blue coats and

broad-striped waistcoats, sitting in their southern gardens on the low

beds of camomile, with the Bible in their hands, their old eyes filled

with mild seriousness, blent with the sunlight of the sweet summer-tide,

is one of the most pleasing pictures of human life. And many a time with

profound awe have I seen the peace of their cottages within, and the

solemn reverence of young and old, when some greyhaired patriarch has

gathered himself up in his bed, and, ere he died, blessed his children.”

One feels disposed to regret that the good old race of Portioners, with

their primitive customs and picturesque surroundings, are fast vanishing

away, and that the little properties on which they lived in modest

independence are now swallowed up and lost in the large ambitious

estates and farms around :—

“In fares the land, to

hast’ning ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates and men decay.”

Thomas received his first

lessons at his father’s knee, and, like so many eminent men, was

educated afterwards at those parish schools which have been for

generations the just pride of Scotland. Pie showed his love of letters

at an early age, by running off one day to the teacher at Bowden, with

his book concealed about his person ; and he was so bent upon

instruction, that his parents, in order to gratify him, took his elder

brother from school, to fill the place of usefulness at home which he

had vacated. After this he attended for a time the parish school of

Melrose. A letter in rhyme, which was kept till worn to shreds by his

surviving brother, James, was his first known attempt at verse-making.

Thomas was no book-worm, however. He excelled in all outdoor sports,

especially in leaping; and he used to attribute the varicose veins and

rheumatic pains from which he suffered much in manhood, to the violent

athletic exercises of his youth. Indeed, the tattered clothes which his

mother was obliged to repair every night, was the only cause of

complaint which she could find in the generous boy, overflowing with

health and spirit. As he grew older, shooting rabbits among the whins,

and fishing in the Tweed, occasionally in the company of John Younger,

the St Boswell’s poet and essayist, were his favourite pastimes; and he

delighted in wandering through the Eildon woods to watch the habits of

birds and insects. His excursions sometimes extended to Williamslee, the

sweet pastoral farm of his uncle, Mr Andrew Paisley, near Innerleithen,

and to the St Ronan’s games, held annually in that vicinity, where

Professor Wilson and James Hogg, in the presence of the Earl of Traquair

and a gallant company from the Forest, performed feats of strength and

agility which far outstripped the Flying Tailor of Ettrick. These were

happy days, spent amid lovely scenes, and he often refers to them in his

writings :—

“Oh to be a boy once more,

Curly-headed, sitting singing

’Midst a thousand flowerets springing,

In the sunny days of yore,

In the sunny world remote,

With feelings opening in their dew,

And fairy wonders ever new,

And all the budding quicks of thought!

Oh to be a boy, yet be

From all my early follies free!

But were I skilled in prudent lore,

The boy were then a boy no more.”

“Ah, yes!” he says in his

old age; “the seeking of saugh wands and the weaving of creels; the

expeditions for hips and haws and sloes; the first games of boglie about

the stacks, and the first coming of the fox-hounds to Eildon Hills, made

my boyish Octobers peculiarly cheery.”* Brothers and sisters were his

companions on these joyous occasions—

“Spilling rich laughter

from their thriftless eyes,”

to use his own delightful

words. He was always a great favourite with them, and sore were the

hearts of the happy family when the day of parting came.

In 1816 Aird went to reside in Edinburgh, which for nearly twenty years

became his second home. There he attended the University, and made the

acquaintance of Thomas Carlyle, his lifelong friend and correspondent.

He was a member of the Dialectic Society, and exchanged to the last

literary communings and kindly regards with Lord Deas and others, his

old combatants in debate. In the middle of his studies he resided for

several months, as tutor, in the family of Mr Anderson, farmer of

Crosscleugh, in Selkirkshire, close to the famous hostelry of Tibbie

Shiel, the paradise of anglers and tourists. Here he frequently met with

the Ettrick Shepherd, and grew as much attached as Wordsworth to the

green braes of Yarrow and St Mary’s Loch, the peaceful beauty of which

lingered fondly in his memory till his dying hour. Aird was designed by

his relatives for the ministry of the Church of Scotland, for which he

always entertained a profound and patriotic attachment. Before quite

completing his academic course, however, he changed his purpose, owing

to a feeling of personal diffidence, and embraced the freedom of a

literary life. The loss of Aird to the noble service of the Church may

be to many a subject of regret, but those who knew the sensitive nature

of the man can understand how he shrank from a position involving so

much prominence and responsibility. The quiet walks of authorship were

more suited to his disposition, and there was a favourable opening at

this time. The fame of Edinburgh as a seat of learning was altogether

unprecedented. The press was pouring forth year by year the unrivalled

works of the author of ‘Waverley;’ the ‘Edinburgh Review,’ supported by

Jeffrey, Brougham, Horner, Sydney Smith, and Cockburn, was carrying all

before-it; and ‘ Blackwood’s Magazine ’ was about to start on its

brilliant career, under Wilson, Lockhart, Hogg, De Quincey, and a host

of celebrated names. In the literary circles of Edinburgh appeared also,

from time to time, the greatest churchman since the days of Knox, the

illustrious Chalmers. The metropolis was in a state of intellectual

ferment, and the whole atmosphere was charged with electricity.

It was natural that a youth of capacity and ambition like Aird should

wish to enter the listed field, and enrol his name among the immortals.

His first venture, published in 1826, was entitled £ Murtzoufle; A

Tragedy in Three Acts: with other Poems.’ Though little regarded at the

time, the volume displays unmistakable genius, and is remarkable for the

maturity of mind exhibited by one who had only reached his twenty-fourth

year. The single piece, “ My Mother’s Grave,” has never been surpassed

in elegiac verse, and deserves a place beside Cowper’s imperishable

lines. This exquisite poem breathes a spirit of yearning tenderness and

intense yet restrained pathos, to be found nowhere else in the author’s

works, and might have been written in tears of blood, so touching is the

cry of filial agony over a parent’s memory :—

“Oh rise, and sit in soft

attire!

Wait but to know my soul’s desire!

I’d call thee back to earthly days,

To cheer thee in a thousand ways!

Ask but this heart for monument,

And mine shall be a large content!

Because that I of thee was

part,

Made of the blood-drops of thy heart;

My birth I from thy body drew,

And I upon thy bosom grew;

Thy life was set my life upon;

And I was thine, and not my own.

My punishment, that I was far

When God unloosed thy weary star!

My name was in thy faintest breath,

And I was in thy dream of death ;

And well I know what raised thy head,

When came the mourner’s muffled tread! ”

In 1827 Aird published

his ‘Religious Characteristics,’ a prose composition of quaint

imaginative power and exalted Christian tone. The work is divided into

two parts. The first part contains six chapters, entitled

Worldly-Mindedness; Indecision ; Pride of Intellect; Antipathy;

Christian Principles; The Attainment of Christian Principles. Part

second contains eight chapters, the subjects being: Charity of Education

Enforced; Need of Earliest Christian Education; Man’s Intellectual

Character; Habits of Intellectual and Moral Power; Application of

Knowledge and General Instruction; First Points of Christian Discipline;

Christian Discipline Continued; General Christian Education — Millennial

Hopes. The style is somewhat marred by obscurities and involutions

characteristic of the author, who was too anxious to condense his

meaning within the narrowest space, forgetful of the Horatian warning—

“Brevis esse laboro,

Obscurus fio.”

But there are many

passages of great splendour and opulence, in which he rises far above

the clouds to the loftiest heights of sacred eloquence :—

“And of all habits this (Worldly-mindedness) is the meanest and most

unworthy of man’s immortal lights. How undignified the old age of such a

man ! The old hills are renewed with verdure. Even the lava-courses are

hid in time beneath vineyards. The dismantled tower of ages gains in

veneration what it loses by literal decay. The pious old man bears on

the venerable tablet of his forehead shadowed glimpses of the coming

heaven. The old worldling—alas ! ’tis he; of him is the contrast. There

is no redeeming symbol or circumstance in his old age: the eye of

cunning, still at its post, almost outliving decay; the old hand, almost

conquering by its unabated eagerness, the palsy of years—trembling in

both ; still closing over gain ; mocking, in the stiffness of its

muscles, the being’s protracted delight to count over so much money his

own, or sorrow to give so much away. . . .

“Ye British mothers! with a praise above your beauty, virtuous wives,

honourable women! to you is the high distinction of being intrusted not

only with the character of a mighty people on earth, but with the first

elements of the kingdom of heaven. Remember the praise of the mother of

the Gracchi and hers who gave her child to God,— the Hebrew mother who

led his boyhood up to the Sanctuary. That little face that sleepeth his

untroubled sleep! What find you in those untrodden lines only stirred by

the faint manifestations of breathing life, for that tear which gathers

slowly from a concentrated heart? Because that little map of peace may

be disfigured by guilt;—because those lines may be heavily trampled,

Sorrow in the hollow cheek, and Shame on the lean eyebrow. Nay, because

he may rise in honour with God and man—mine own son— and blessed is the

mother that bore him. O woman ! as thou wouldst the latter and not the

former; as thou wouldst lean on the shoulder of his noble manhood in

presence of the people, with the impressive weakness of delight; as thou

wouldst have his young foot haste like a silver arrow to do good;—know

thy duty of first and best instruction according to the High Oracles. .

. .

“Thou Mysterious Inhabitant on our earth! Incalculable Spirit, imbowed

and enshrined in the form of our mortality! Jesus of Nazareth! who shall

declare the simple but sublime glory of Thy life? With the countenance

of a little child, what was in Thy heart!

The poet with his vague praises may turn to the setting sun; but for

whose sake is this beauteous world kept up, and the sun shining on the

just and the unjust? For Thine, for Thine, Jesus of Nazareth! Every

sweet tone in nature comes forth from Thy responsibility. Every little

singing-bird has in Thee more than a double creator. Thou art Alpha and

Omega in the strangely-wrought song of Time and its spheres. There is in

this life no consistent alternative between a distinct denial of the

divine and mediatorial attributes of this Being of Mercy, and the

profoundest respect for His cause and commandments.”

Aird was now brought into public notice. His book received a glowing

eulogy in ‘Blackwood’ from Professor Wilson, who, from this time, became

the fast friend of the author, and consulted with him repeatedly

afterwards, particularly while writing his own fine papers on Spenser

and Burns. Aird, who had recently made the acquaintance of Mr Blackwood,

the eminent publisher, reviewed Pollok’s ‘ Course of Time ’ in the same

number of the Magazine,1 and supported himself by private teaching and

contributions to the periodicals. Upon the death of Mr James Ballantyne

in 1832, he edited for a year the ‘Edinburgh "Weekly Journal/ in the

property of which Sir "Walter Scott once held an important share. On

this occasion he received the following letter from Dr Moir, author of ‘

Mansie Wauch/ whose biography he was afterwards to write:—

“Musselburgh, 12th Feb. 1833.

“My dear Sir,—I take shame to myself for not having several days ago

answered your kind note, informing me that you had accepted the

editorship of the ‘ WAekly Journal.’ I rejoiced most heartily to hear

it, which I did a day or two before from Professor Wilson, and in the

sincerity of my heart wish you every comfort, success, and distinction

in its management. I have no doubt that for some time you will find a

thousand petty difficulties, but one by one these will disappear before

the wand of experience, and week after week you will be enabled to step

out more securely. Need I say, if there is any way in which I can at any

time lend you a helping hand, that you have only to command my services.

The hurry and bustle of a medical life, which makes no distinction

between night and day, Sunday and Saturday, puts it out of my power to

dedicate to literature much time; but I must be very hurried indeed if,

at the request of a friend, a paragraph or two refused to be

occasionally forthcoming.”

In the midst of his avocations, Aird found leisure to explore the

romantic environs of the metropolis —to visit the scenes of the ‘ Gentle

Shepherd ’ at Habbie’s Howe—and to attend, with the poet Motherwell, the

great dinner at Peebles in honour of James Hogg, where Wilson presided.

But his footsteps were directed more frequently to Roxburghshire when

the summer came round. The glad welcome of his dear Border home was

sweeter to him than all the laurels of Edinburgh, and eagerly did he

accompany his brothers for a season to the “Old Scottish Village,” close

by the murmuring Tweed. At a certain turn in the road, the merry-hearted

youths tossed their caps with shouts into the air, when the triple peaks

of the Eildons burst upon their view—those wonderful hills which the

wizard cleft in three, as if he meant them to be the wardens of the

Border, and the special guardians of Dryburgh, Melrose, and Abbotsford.

In one of his recent poems, Aird thus describes their striking beauty :—

“Above the mist the sun

has kissed

Our Eildons—one, yet three:

The triplet smiles, like glittering isles

Set in a silver sea.

Break, glades of morn; burst, hound and horn;

Oh then their woods for me!”

In 1835 Aird finally left

Edinburgh for Dumfries, and, upon the recommendation of Professor

Wilson, became editor of the ‘Dumfriesshire and Galloway Herald,’ a

weekly journal professing Conservative principles. In the practical

management of the paper, he was loyally assisted by the publisher, Mr

Craw; and to the discussion of public questions he invariably imparted a

high-bred honourable tone. Of his profession Aird entertained a lofty

estimate. “The newspaper,” he said, “was the gospel of God’s daily

providence working in man’s world;” and in accordance with this high

ideal he set himself to his task. By conviction he was a stanch

supporter of Conservatism in Church and State, and when occasion

required he could wield his pen with startling vigour, dismissing his

subject and opponents in a few pithy and trenchant sentences. To quote

his own confession, he was “no cheek-surrendering Quaker;” and in the

unhappy ecclesiastical disputes of 1843 even Hugh Miller felt the weight

of his arm.

But controversy, after all, was too coarse an element for a nature so

refined as his. The arena of party strife was not a congenial field for

one whose heart was far away in the realms of poesy; and the ‘Herald’

became famous among journals for its literary reputation, rather than

for its political authority. Its pages were enriched with some of his

choicest verses and criticisms, and the generous editor was always glad

to receive the contributions of the youthful talent which gathered

around him. Many individuals who now occupy a conspicuous position in

the Church, in medicine, and the law, were indebted to him for their

first introduction to letters, and will remember with gratitude the

training and encouragement which they got from their kind patron and

friend. His correspondents hailed, as he used to say, “from the northern

Tay to the classic Cam:” and amongst them may be mentioned the names of

Dr Moir, the Delta of ‘ Blackwood’s Magazine; ’the Rev. George Gilfillan

of Dundee; the Rev. Thomas Grierson of Kirkbean, author of ‘Autumnal

Rambles among the Scottish Mountains;’ Mr Bell Macdonald of Ram-merscales,

the accomplished linguist; the Rev. Dr Duncan, Dumfries; Dr Ramage,

Wallace Hall; Mr Thomas M'Kie, Advocate; Professor Charteris, Dean of

the Chapel Royal; Dr Clyde; Mr Stewart of Hillside; Rev. J. W. Ebsworth;

Dr Mercer Adarn; the Rev. Dr Menzies of Hoddam, translator of Tholuck’s

‘Hours of Devotion,’ &c. Robert Burns, the eldest son of the bard, who

bore a striking resemblance to his father, and inherited a share of his

poetic talents, occasionally contributed verses to the paper. The

following lines by the editor, among many more exquisite morsels,

appeared in the columns of the ‘Herald’ without his name, and were never

republished:—

May Morning.

“May morn, how fresh and fair,

With dews and honey smells,

And sunny crystal air!

The little birds are at their carollings;

The booming wild bee spins his airy rings:

Come forth and see.

High hanging woods, the gleams

Of opening valleys with their branching streams,

White cities shining on the bending shore,

Away far fused the ocean’s silver floor,

For thee shall glorify the hour,

Young Queen of Beauty, from thy virgin bower.”

Dumfries proved an

attractive abode to one who was devoted to literature and to the

contemplative life of the recluse. There are few fairer places in

Scotland than the rare old town, called fondly by its citizens the Queen

of the South. The ancient burgh, with a population of some 16,000 souls,

sits on the left bank of the Nith, thirty-three miles to the north of

Carlisle. The green hills of Galloway slope gently to the west, while

from the rising ground you see the proud form of Skiddaw and the

Cumberland range, and catch a whiff of the Solway tide as it sweeps past

Criffel and the Kirkcudbright shore. The town itself, which wears a

quaint Continental air, is rich in Border memories and old-world

associations, recalling the days when the Maxwells fought with the

John-stones, and the Stuarts with the House of Hanover. Prince Charlie’s

room in the Commercial Inn is still to be seen; Comyn’s Court, off

Friars’ Vennel, where Bruce stabbed the traitor; the time-stricken

Bridge, erected by the pious Lady Devorgilla; and College Street in the

adjoining burgh of Maxwelltown, so honeycombed with subterranean

passages, that Townshend, the clever detective officer, declared it to

be as safe a hiding-place for a thief as the Seven Dials in London.

Then, too, in the immediate vicinity, we have the noble castle of

Caerlaverock, and the beautiful abbeys of Lincluden and Sweetheart. But

the name of Burns is the glory of the district. Here he lived for

upwards of five years, and here he died in 1796, and was buried in old

St Michael’s churchyard.

Aird took kindly to his adopted home, and soon learned to love its sweet

river-walks, its glimpses of the sea, and sylvan beauties. Shunning

society and its temptations, he courted the Muses in the shade, and the

result of his studious life appeared in 1845 'm ^ie publication of ‘ The

Old Bachelor in the Old Scottish Village.’ This work brought Aird for

the first time into general celebrity, and its charm consists in its

admirable prose delineations of Scottish character, and its descriptive

sketches of the various seasons. The tales of the author, like his

dramatic pieces, are defective in plot and construction, and do not

possess the same interest for the reader, though containing memorable

passages. Take this vivid description of October, his pet month in all

the year, with its rustling breezes and whirling leaves :—

“Having no dislike to the coming-on of winter, October is to me the most

delightful month of the year. To say nothing of the beauty of the woods

at that season, my favourite month is very often a dry one, sufficiently

warm, and yet with a fine bracing air, that makes exercise delightful.

And then what noble exercise for you in your sporting-jacket! To saunter

through the rustling woodlands; to stalk across the stubble-field,

yellow with the last glare of day; to skirt the loin of the hill, and,

overleaping the dyke, tumble away among the ferns, and reach your door

just as the great, red, round moon comes up in the east,—how

invigorating! I say nothing of the clear fire within, and the new

Magazine just laid on your table. Moreover, October is associated with

the glad consummation of harvest-home, and all the fat blessings of the

year—not forgetting the brewing of brown stout. Altogether, October is a

manly, jolly fellow ; and that Spenser knew right well, as thus

appears:—

‘Then came October, full

of merry glee ;

For yet his noule was totty of the must,

Which he was treading in the wincfat’s sea;

And of the joyous oil whose gentle gust

Made him so frolic.’

What fine, quaint,

picturesque old words these are!”

In the following passage

the Old Bachelor describes the witchery of the summer gloaming, and the

strange eerie feeling which creeps over him when he finds himself alone

in the haunted Border-land, amid the mysterious silence and shadows of

the night:—

“After our simple family devotions are over, I usually saunter forth to

see the night. How still the stillness of the midsummer evening! The

villagers are all abed. The last tremblings of the curlew’s wild bravura

have just died away over the distant fells into the dim and silent

night. Nothing is now heard but the momentary hum of the beetle wheeling

past, and, softened in the distance, the craik of the rail from the

thick dewy clover of the darkening valley. The bat is also abroad, and

the heavy moths, and the owl musing over the corn-fields; but, instead

of breaking, they only solemnise the stillness. The antique houses of

the hamlet stand as in a dream, and the trees gathered round the

embowered church as in a swooning trance. In such a night, and in such

an hour, the church bell, untouched of mortal hands, has been heard to

toll drowsily. I feel a softening and sinking of the spirit; and hear

the beating of my heart as if I were afraid of something, I know not

what, just about to come out of the yawning stillness. Hurriedly I glide

into the house, and bolt the door. And, when I lie down and compose

myself on my bed, the fears of death creep over me.”

The ‘Old Bachelor’ was followed in 1848 by a full edition of his poems,

on which Aird’s fame as a man of genius principally rests. Of these the

world has, with a sure instinct, singled out for its wonder and

“Othuriel” and other poems were published in 1839.

Here the poet put forth

all his strength, and appeared as a consummate artist;—

“For in him were passion

and music and power,

And he spake like a king in his conquering hour.”

The “Devil’s Dream” is a

poem of daring originality, and, in point of epic grandeur, has often

been compared with the “Inferno” and “Paradise Lost.” Though only a

fragment, it is a colossal one, and displays in its conception and

terrific imagery the splendour of a bold imagination. There are single

lines in it which seem to illuminate the page, as if written in

characters of fire :—

“Above them lightnings to

and fro ran crossing evermore,

Till, like a red bewildered map, the skies were scribbled o’er.”

The poem opens with much

magnificence :—

“Beyond the north where

Ural hills from polar tempests run,

A glow went forth at midnight hour as of unwonted sun;

Upon the north at midnight hour a mighty noise was heard,

As if with all his trampling waves the Ocean were unbarred;

And high a grizzly Terror hung, upstarting from below,

Like fiery arrow shot aloft from some unmeasured bow.

’Twas not the obedient

Seraph’s form that burns before the Throne,

Whose feathers are the pointed flames that tremble to be gone:

With twists of faded glory mixed, grim shadows wove his wing;

An aspect like the hurrying storm proclaimed the Infernal King.

And up he went, from native might, or holy sufferance given,

As if to strike the starry boss of the high and vaulted heaven.”

The picture of the Arch

Fiend, in his ruin and his pride, chafing in vain against the iron bars

of the universe; defying the Almighty to His face, yet impotent to

resist His serene, inexorable will, is a sublime creation, and almost

unique in literature :—

“. . . O’er his head he

saw the heavens upstayed bright and high;

The planets, undisturbed by him, were shining in the sky;

The silent magnanimity of Nature and her God

With anguish smote his haughty soul, and sent his Ilell abroad.

His pride would have the works of God to show the signs of fear,

And flying Angels to and fro to watch his dread career ;

But all was calm: He felt night’s dew upon his sultry wing,

And gnashed at the impartial laws of Nature’s mighty King;

Above control, or show of hate, they no exception made,

But gave him dew, like aged thorn, or little grassy blade.”

Passing by “My Mother’s

Grave,” that marvellous product of Aird’s youthful genius already

referred to, we come to two noble poems, the “Demoniac” and

“Nebuchadnezzar,” and to his delightful “Summer Day” and “Winter Day,”

“Frank Sylvan,” “The Swallow,” “The River,” and “The Holy Cottage.” He

is always at home among the scenes of nature :—

“Yet oh, from age to age,

that we

Might rise a day old earth to see!

Mountains, high with nodding firs,

O’er you the clouded crystal stirs,

Fresh as of old, how fresh and sweet!

And here the flowerets at my feet.

Daisy, daisy, wet with dew,

And all ye little bells of blue,

I know you all; thee, clover bloom,

Thee the fern, and thee the broom :

And still the leaves and breezes mingle

With twinklings in the forest dingle.

Oh through all wildering worlds I’d know

My own dear place of long ago.”

Sometimes, in the fewest

strokes, he hits off a character or incident with inimitable point. The

following picture of cottage life, entitled “Grandmother,” and given

here in its original and better form, is quite perfect in its way, a

simple and touching vignette:—

“Far through the snows of

winter come

To share his widowed Grannie’s home,

The Orphan Boy lays down his head

Weary on his little bed.

Oft looking out, with modest fear,

He sees her anxious face severe,

I,ate at her work, as if ’twere due

To such a heavy burden new.

Her lamp put out, the clothes are prcst,

How kindly, round his back and breast ;

Her face to his, so loving meek,

He feels a tear drop on his cheek.

Sobbing, sobbing, all for joy,

.Sobbing lies the Orphan Boy :

No more sorrow, no more fear,

Such power is in that simple tear!

Rise, morrow, rise! Upspringing he

Down to the death her help shall be.”

It is to the honour of

Thomas Aird that his poetry, as his life, was intensely religious and

pure. To repeat the fmc remark applied to him by Wilson, he was “imbued

with that deep devotion which was the power and the glory of so many of

our divine men of old.” Ilis genius was consecrated to themes of supreme

interest for man; and it is natural to cherish the hope that, amid the

wreck of human trivialities, his noble poems may survive and perpetuate

the name of their author in the coming time :—

“His ears he closed to

listen to the strains

That Sion’s bards did consecrate of old,

And fixed his Pindus upon Lebanon.”

The present edition of

the poems, which is the fifth, is now presented as corrected and

arranged by the author’s hand, and contains several pieces which have

not been previously published. Of these the chief are: “The Goldspink

and Thistle;” “Our Young Painter;” “The Lyre;” “Monograph of a Friend;”

and “The Shepherd’s Dog.”

In 1852 appeared Aird’s Life of Dr Moir, who expired while on a visit to

his friend at Dumfries in the previous year. The work, which was

undertaken on behalf of the family of the deceased, was a labour of

love, admirably executed, and is interesting for its reminiscences of

Galt, Warren, Macnish, Macginn, Michael Scott, Hamilton, and the later

contributors to 'Blackwood’s Magazine.’ Dr Carruthers of Inverness, a

valued and accomplished friend, communicates the following interesting

letter on the subject:—

“Strathpeffer, by

Dingwall, May 7, 1852.

“My dear Sir,—The quiet little village from which I write this, is a

sort of Highland Moffat, frequented in summer by the people of the

north, who think their rheumatisms and other ailments much benefited by

a few weeks’ use of the spa water and inhalation of the fresh mountain

air, free from active business, late hours, and dinner-parties. Among

other idlers, my wife and I are here; and as fortunately rain falls fast

this forenoon, freshening the parched braes and shrivelled trees, I was

beginning to feel somewhat dull and drowsy at the prospect of a long day

without a walk, when luckily in came the post with three new

volumes—your memoir and works of Delta, and Peter Cunningham’s story of

Nell Gwyn ! There could not be a greater contrast in the style and

subject of books, but both were heartily welcome. Nell was the best and

most Protestant of Charles’s vile seraglio; and Moir I had long loved

and wished to hear something more of. His poetry I am not so much

acquainted with as I should be, for I was in England during his best

‘Blackwood’ days; and not seeing the magazine then, I lost some of his

verse, and have not since had the resolution to bring up the arrear.

However, now I have him in extetiso, with the addition of your memoir,

which, I need hardly say, 1 have just read at one sitting. What my

impressions are after the perusal I shall tell you, without regard to

method or sequency, as I will take up the book again more deliberately

and carefully. I think you have done your part admirably, erring only on

the side of too little, and not falling into the common sin of

indiscriminate panegyric. Some of your brief illustrations and episodes

have much felicity of expression. Your allusion to Jeremy Taylor, for

example (xxiii and xxiv), is very fine, and also the cento on Sculpture

farther on in the memoir. Your estimate of Moir, personally and

poetically, is also marked by sound discrimination. What an excellent

man he seems to have been ! so cheerful, active, and benevolent, and his

well-balanced mind so alive to all the finer sensations and impulses of

an imaginative nature, without neglecting one moral or social duty. I

was not prepared to find such a solid substratum of homely common-sense.

This is strikingly evinced in his remarks on Coleridge’s monologues and

Emerson’s transcendentalisms. I suspect even Mr Carlyle would not have

fared much better with him, though possessing more of the carlehemp of

man. I may mention to you that I have heard three remarkable men speak

of Coleridge’s oral philosophy in a very depreciatory style. These were

Rogers, Campbell, and Allan Cunningham. Coleridge must, however, have

been great at times, when he broke out from his metaphysical mist, and

had a congenial auditor.

“Are you not wrong in your allusion to Swift at page lx? I have not

access to books here, but I think the saying was applied to Sir John

Denham, who was eulogised as coming out as a poet, like the Irish

Rebellion, threescore thousand strong. Turn up Johnson and satisfy

yourself. The exclamation about Hogg— ‘Ah, Hogg! ah, James! we miss you

sadly’—rather jarred on my critical sense. Is it not too colloquial for

the grave didactic page in which it appears? Look, also, at your

concluding sentence. By putting Moir among such a crowd of names, so

various in rank and general estimation, you give him no determinate

place— in fact, bury him. You see I avail myself of our chartered

liberty of the press—our editorial infallibility—with a vengeance.

“But I owe you many thanks, my dear sir, for your introduction to so

lovable a man as Moir. I now seem to know him well, and I shall always

think more highly both of him and his biographer. There is too often so

much that is painful or disagreeable in the lives of authors—especially

in the case of second-rate poets— that it is delightful to have so pure

and unmixed a portraiture as that which you have presented the world

with. It will give the deceased a fresh lease of popularity, and long

operate as a bright and winning example. —Ever yours affectionately,

“Robt. Carruthers.”

Aird maintained to the last his early friendship with his distinguished

countryman, Thomas Carlyle. They usually met every season in Dumfries,

during the annual visits of the latter to his relatives in Scotland, and

the two delighted to recall, in their pleasant interviews, the memories

of bygone days. Mr Carlyle, whose courtesy I beg to acknowledge with

profound gratitude and respect, has given me permission to publish the

following correspondence with his friend :—

“5 Ciif.vne Row, Chelsea, London,

22d fan. 1837.

“My dear Sir,—. . . Thanks for the mute indications of remembrance we

have often had from you. Go on and prosper ! that is always our wish (my

wife’s and mine) for one whom we love well. The unspeakable Book2 is

fairly at press, thank Heaven. In six weeks more my share of business

with it will be over for ever and a day ! It will be worth little to

most men, to all men : except to me the incalculable worth of troubling

me no more. I saw Gordon since I saw you. My kind remembrances to him.”

“Templand. 6th Aug. 1839.

“My dear Sir,—You were expected hereon Friday last; by me rather more

confidently than perhaps your last words warranted; by Mrs Welsh and

others more confidently still than that report of mine,—with a

confidence of certainty namely;—Hope telling us all his usual

‘flattering tale!’ Dr Russel was invited here to dine with you on Friday

and had to dine without you; Dr Mundell of Wallace flail had an

invitation left for you to dine on Saturday, &c. &c.; and it was all a

mere misreport and misapprehension of reports of the oral utterance of

man, a most imperfect organ for representing the Future with, for even

explaining the present with! Your letter arrived on Saturday morning

with the newspaper, for which and its predecessor many thanks. Dr Russel,

we learn, is also apprised of your true movements now. I grieve to say

that on Friday next 1 have but little chance to be here. I am to be in

Annandale on Wednesday or Thursday ; so roll the bowls,—perversely for

us. But my wife will be here, right glad to see you, and Mrs Welsh, and

other friends. I hope to see you in passing through Dumfries some time

after Friday; and that after Friday the future will not be poorer than

the past has been, but richer, as it may well be.

“I am not so well in health as I expected; nor is my wife at all very

well. We must, do the best we can. This piece of the Universe called

Nithsdale, in this section of Eternity called August 1839, is very

beautiful ; doubly beautiful to me whose head has long simmered half-mad

with brick wildernesses, dust, smoke, and loud-roaring confusion that

meant little. Good be with you, my good friend.—Yours always truly,

“T. Carlyle.”

“5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, 20th Jan. 1840.

“Dear Mr Aird,—It is only half an hour since your kind present, dated

Christmas, arrived here. I have not a single moment to myself at

present. I know not how many people all talking round me, &c. &c., but

it seems better to write you the message that your book has arrived, has

been welcomed, and lies waiting judgment,—not waiting good and best

thanks from both of us. On the whole, I am right glad to see you in

independent print again; and though I like Prose better than Poetry

(sinner that I am), and read very little of the latter, I must except

anything in the one style or the other from friend Aird. Why should you

not write to me now that it costs only a penny? With many compliments,

wishes, and thanks.”

“5 Cheyne Row, Ciielsea, 1st May 1840.

“Dear Mr Aird,—Accept many thanks for your long kind letter; a welcome

proof of your remembrance of us. When you read the inclosed Program,3

and think that my day of execution (‘ Do not hurry, good people ; there

can lie no sport till I am there !’) is fixed for Tuesday first, you

will see too well the impossibility of writing any due reply. Alas, I am

whirling; the sport of viewless winds ! It is the humour I always get

into, and cannot help it. Some way or other in four weeks more we shall

be through the business ; and hope not to resume it in a hurry. For

lecturing, as indeed for worldly felicity in general, I want two things,

or perhaps one of them, either of them would bring the other with it and

suffice : Health and impudence. We must do the best we can ; and ‘be

thankful’ always, as an old military gentleman used to say, ‘that we are

not in Purgatory.’ We noticed Gordon's4 promotion, with pleasure, in the

‘Herald.’ I have never heard a word from the man himself ; he will suit

the business well, and the business him ;—a good honest soul as is in

all Scotland or any other land. You are happy to be in green quiet

places : for me, ah me ! I am here in the whirlwind of every kind of

smoke, dust, din, and inanity; ‘I can’t get out !’ We shall meet if we

can this summer ; but it is uncertain, like all things.—Yours always,

“T. Carlyle.

“P.S.—My wife is now pretty well; improving always with the progress of

the sun. We had the coldest March and the hottest April I can remember.

I say nothing of I thuriel + at present, tho’ so much were to be said !

You will write a right Prose Book one day! I always hope that Poetry is

out;—is not the very Bible in prose?”

“Chelsea, 14/// Nov. 1845.

“Dear Aird,—I will attend well to what you say about Gilfillan ; and

certainly if I can do him any good on such an occasion, it will be a

duty as well as a pleasure to me. My personal connection with Reviews,

&c., has altogether ceased, for a long while; nor indeed is there any

very clear way of seeking to give furtherance to a man of real merit,

amid the crowd of empty pretenders and of false judges that we have at

present. But it is the more incumbent on one to do what is possible; and

in that I will endeavour not to fail as occasion serves. . . .

Reviews, I believe, do little good nowadays, except by the extracts they

give, which keep alive some memory of the Book till people judge of it

for themselves. Our address for the next two or three weeks is—Hon. W.

B. Baring, Bay House, Alverstoke, Hants (we are setting out thither for

a little more of the country to-morrow). Or Chelsea, the old address,

will always find us after a short delay. John* is still ‘gravitating’

towards you; will alight in Dumfries, I believe, by-and-by—when the fogs

have become heavy enough. He is very busy with Dante, &c., at present,

and seems lazy to move. This, in spite of its fogs, is the Paradise of ‘

men at large,’ this big Babylon of ours.

“We have in the evenings gone over the ‘Old Bachelor in his Scottish

Village,’ and find him a capital fellow of his sort. The descriptions of

weather and rural physiognomies of nature in earth and sky seem to me

excellent. More of the like when you please !

“My wife sends many kind regards to you; take many good wishes from us

both. — Yours always very sincerely, T. Carlyle.’

*Mr Carlyle's brother, Dr Carlyle.

“Chelsea, 15 Nov. 1848.

“My dear Aird,—I have received your volume of poems: many thanks to you

for so kind and worthy a gift, and for the kind and excellent

letterwhich came to me the day after. I have already made considerable

inroads into the ‘Tragedy of Wold,’ and other pieces: I find everywhere

a healthy breath as of mountain breezes ; a native manliness, veracity,

and geniality which, though the poetic form, as you may know, is less

acceptable to me in these sad times than the plain prose one, is for

ever welcome in all ‘forms/ and is, withal, so rare just now as to be

doubly and trebly precious.. But your delineations of reality and fact

are so fresh, clear, and genuine when I have met you in that field, that

I always grudge to see such a man employ himself in fiction and

imagination,—when the ‘reality/ however real, has to suffer so many

abatements before it can come to me. Reality, very ugly and ungainly

often, is nevertheless, as I say always, God's unwritten poem, which it

needs precisely that a human genius should write and make intelligible

(for it would then be beautiful, divine, and have all high and highest

qualities) to his less-gifted brothers! But what then? Gold is golden,

howsoever you coin it; into what filigree soever you twist it. I know

gold when I see it, one may hope. For the rest, ‘a wilful man must have

his way.’ And, indeed, I know very well I am in a minority of one with

this precious literary creed of mine, so cannot quarrel with your faith

and practice in that respect. Long may you live to employ those fine

gifts in the way your own conscience and best deliberated insight

suggests!

“Your new lodging, commanding a view of Troqueer and the river, must be

a welcome improvement on the former, which was of the street streetish :

the very sound of the Cauld* is a grateful song to one’s heart;

whispering of rusticities and actualities; singing a kind of lullaby to

all follies and evil and fantastic thoughts in one! You speak of my

getting back to Scotland: such an imagination dwells always in the

bottom of my heart; but, alas! I begin often to surmise that it is but

perhaps imaginary, after all ; that I am grown a pilgrim and sojourner,

and must continue such till I end it ! That shall be as it pleases God.

“I get very ill on with all kinds and degrees of work in late days; in

fact, the aspect of the world, from one end of it to the other,

especially this last year, is hateful and dismal, not to say terrible

and alarming, and the many miserable meanings of it strike me dumb. The

‘general Bankruptcy of Humbug ’I call it; Economics, Religions, alike

declaring themselves to be Mem Mcne; all public arrangements among men

falling as one huge confessed Imposture, into bottomless insolvency,

Nature everywhere answering, ‘ No effects !’ This is not a pleasant

consummation ; one knows not how to speak of this all at once, even if

it had a clear meaning for one !—Good be with you, dear Aird. Tell my

sister you have heard from me, and that she must write.—Yours ever

truly, T. Carlyle.”

Professor Wilson, then in search of information for his essay on Burns,

visited Dumfries in October 1840, and writes to Aird on his return to

Edinburgh. The death of his wife had saddened his brilliant spirit by

this time, and given a pensive colouring to that eloquence which Hallam

compares to “the rush of mighty waters: ”—

*Weir across the Nilh.

“My dear Mr Aird,—We arrived all safe at Gloucester Place about 8

o’clock. From Thornhill to Edinburgh it rained incessantly, but not

heavily, all the way. Goliah was sheltered by the luggage, but we were

all sorely crushed by increasing population. For some days I suffered

from sore throat and cold, but am myself again, though my former self

nevermore. I find that, much to my annoyance, I have to deliver an

address at the opening of the Philosophical Association on the 10th, I

believe, of November, on what nobody can tell me, nor do I at present

know. Would you turn the matter over in your mind, and in a few days

tell me in the form of a letter or letters anything that may occur to

you thereon. A few hints on any subject often suffice to set my thoughts

allow. A pitcher or two of water may fang the well. What I want is some

heads or rmroi on which to dissert a little. Try to give me your

opinion, and I will try to construct a passable panegyric. I send you

the report of a large assemblage last week. The directors besought me to

give the memory of Pitt, and then, without meaning any disrespect to him

or me, placed it 18th on the list; so that when it came to me, it was

past 10 o’clock at night. I know too well what a hopeless task it would

be for Mercury to start at that hour to an exhausted audience, so T

flung twenty minutes of an intended speech overboard, and confined

myself to what you will see. I believe my good sense was appreciated by

all, though at the time some thought I might have spoken longer. As it

was, it was better received than the able rhetoric of Macaulay. I was

happy to see you, and to see you well and happy.—Yours affectionately,

John Wilson.”

The Rev. George Croly, whom Aird calls “the brave old Irishman,” is well

known as the author of ‘ Salathiel,’ and a contributor to ‘ Blackwood.’

He thus expresses to Aird his opinion of some modern poetry, in terms at

once vigorous and refreshing :—

“London, 25th Feb. 1856.

“I have this morning received your very obliging note, and will have

great pleasure in receiving your volume, which I presume is still on the

way. I have seen hitherto only fragments of your works, the disjecta

membra poctce, which gave me a high anticipation of the treat that is

reserved for me in the perusal of the whole. Our very clever friend

Gilfillan and I differ in some points with respect to poetry. He seems

to be captivated by the mystical, oracular, half-cloudy and

half-meteoric poetry of the ‘ Festus ’ school. He may be right, but I

find it difficult to delight in what I cannot at all comprehend, where

every sentence is an enigma, and every figure is so swathed in

eccentricity of epithet, that I can discover neither visage nor limb. I

am heretic enough to think that ‘ communi scnsu plane caret' is a

formidable drawback, and that to be intelligible to common capacities is

at least a matter that common capacities may be fairly entitled to

require. It always seems to me that haziness of expression is connected

with weakness of conception. The Gods even of Homer never wrap

themselves in clouds, but when they can no longer stand and brave the

open field.”

Professor Blackie also writes in a strain which would have cheered the

heart of Croly and of the author of ‘ Firmilian: ’—

“Edinburgh, 43 Castle Street, 4th March.

“Mt dear Sir,—Accept my best thanks for your poems which I value highly.

I am a true Greek with regard to the divine art, and consider that

poetry is only another mode of wisdom and health, and whatever qualities

it has, may not want that fine music and harmony which belongs to these.

I am a decided enemy of the ‘spasmodic school,’ as my friend Aytoun

calls it—of all poetry however sublime, and however intense, and however

brilliant, that is not wise, healthy, and moderate. I need not say that

I value yours very highly, for it is entirely free from that tone of

exaggeration and morbid excitement which mars the enjoyment of so much

of the versified thought and feeling of the present day.

“I am very much blocked up at present, and have no freedom to float at

ease upon the sunny waves of your verse; but I mean to run wild among

the Highland hills when the summer comes, and shall not forget to take

your happy volume in my pocket.

“When you come to Edinburgh, be sure to knock me up,—And believe me ever

yours sincerely,

“J. S. Blackie.”

“I have many pleasant recollections,” writes Mrs Smith, of Whitehaven,

Air Aird’s attached niece, “of long country walks with my uncle, and how

in the evenings he would saunter up and down in the old long room

overlooking the Cauld, composing as he sauntered. By-and-by he would sit

down and write out his thoughts; then say to me, ‘Listen now, darling.’

And he would read over what he had written, and ask if I noted the

points he wished brought out, and to which he had called my attention

when walking together. Next morning I would hear him pacing his bedroom

an hour or two earlier than usual; and perhaps, after breakfast, I would

be called upon to listen to the same thought expressed more fully and

clearly. And so he went on, carefully pruning away every unnecessary

word, until the point or thought was clear and distinct as a picture.”

Except the necessary paragraphs once a-week for his paper, Aird wrote

little after fifty years of age, partly owing, perhaps, to his secluded

habits, and partly to circumstances of health. In appearance he was a

strong man, of a tall and handsome person, with a beautiful head and

striking presence. Like his own “Frank Sylvan,” he lived much in the

open air; and his notable figure, which attracted the attention of the

stranger, proclaimed the athlete of younger days. But the active frame

was united to a high-strung nervous temperament, which unfitted him for

continuous labour, and made him painfully sensitive to varied forms of

suffering. Sleeplessness, arising from several causes, particularly from

cock-crowing, was for many years the bane of his life; and though he

would smile good-humouredly when the enemy was gone, the consequences at

the time were sufficiently serious. “I lie down,” he said to me, “in a

state of expectancy, and, just when I am going to fall over into

delicious slumber, some creature of the night (cock or cat) is sure to

raise aloft its voice, and drive me to distraction.” At this time he was

in a state of extreme depression,—“on the brink,” as he expressed it,

“of madness and despair,”—owing to the want of sleep, which he had

courted for several nights in vain at the houses of various friends; and

it was not till he fled to a quiet suburb of the town that he obtained

the wished-for repose. But the calm succeeds the storm ; and when his

spirits had leisure to rise again, he would tell the story of his wrongs

with inimitable effect, pouring maledictions on his tormentors, the

ill-omened birds and chartered libertines of the night. He used to say

that Mr Carlyle suffered from the same nocturnal grievances, and when

living in Edinburgh, went to reside for the sake of peace in the

outskirts of the city, whence, however, he was speedily routed by the

cries of defiance which rang from farmyard to farmyard. Even in his

poems he returns to the charge, and, half in jest, half in earnest, vows

vengeance on the whole feathered tribe, with graphic and irresistible

humour:—

“Lo! chanticleer, his

yellow legs well spurred,

Leads forth his dames along the strawy ways,

He claps his wings; he strains his clarion throat,

His blood-red comb inflamed with fiercer life,

And crows triumphant: Soul-distressing sound,

When in the pent-up city, ill at ease,

Your keen and nervous spirit cannot sleep,

Hearing him nightly from some neighbouring court!

Oft have we wished the

gallinaceous tribe

Had but one neck, and that were in our hands

To twist and draw: the morrow’s sun had risen

Upon a cockless and a henless world.

And yet the fellow there, so bold of blast

To sound the morn, to summon Labour up,

Is quite a social power : we’ll let him live.”

It is thus he writes to

Mr Smith, of Whitehaven, on his return to Dumfries, after an unlucky

visit to Cumberland:—

“23d 'June 1856.

“My dear William,—I travelled on defeated yet dogged, and went

slaistering [bedaubed] down to Mountain Hall in the evening. However, I

slept ten hours of blessed sleep, and thus stayed at once one of those

fits which defy opiates now, and fill my soul with terror. It was a vast

imprudence to venture from home so soon after my late harrowing up. And

how I do smile (well pleased) at you healthy unconscious people who

could not tell me, in answer to my preliminary inquiry, that the

Philistines were to be upon me. I have received your note with Mr R.’s

theory of supper. The only theory for me is darkness and quiet. With

them I can sleep better than the most of people. Without them, all the

cheese in Holland and all the porter in London would do little for me.”

The Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee, a dear and intimate friend of the

author, has most kindly favoured me with a perusal of Aird’s

correspondence with him, extending over a period of thirty years.

The following extracts will serve to show, amongst other matters of

interest, the soundness of his critical judgment upon literary

questions, as well as the masculine vigour of his style :—

“Dumfries, %ih Feb. 1841.—Rev. and dear Friend,—

. . . As I merely glance at provincial journals, I did not observe the

strictures on you in the . Such gross malignity can do you only good,

and no harm. To the man who has written such a paper on Coleridge

immediately after such a diatribe, I need not say—Courage ! Take no

notice whatever of the vermin. Neither he nor all the world can touch a

hair of your head, if you be true to yourself. ‘The great soul of the

world is just.’ Thanks to dear Billy of Avon for that. My first

impression was to add a Note of my own to your papers on Coleridge ; and

unless he were made of cast-metal, I think I could make the creature

blush. But now I see it is far better to let your papers soar away in

their owrn silent magnanimity, and tell their own quiet story of joy,

and abash the puny detractors. You are now quite safe from anything he

can say against you. Moreover, as venom seems his spirit, he might

rejoice to return to the subject in answrer to my Note. ... As I am no

cheek-surrendering Quaker, however, I may think it my duty ... to call

the fellow to account. It will help me all the better to do it well that

you have before then got acquainted with Christopher North. . . . I fear

human nature is no better anywhere else than at . Many a time have I

thanked that terrible old fellow, Bentley, for saying in the rushing

face of every ninth wave of his many calamities, ‘Well, I think I have

got through worse than this yet.’ So, courage with old Bentley!”

“25th Feb. 1842.—Let me now first of all acknowledge ‘ Brougham and

Vaux,’ who comes from your hand, I think, in ‘strength and state.’ You

have missed none of the great lineaments, and you have ploughed them all

out deep and strong. The finer peculiarities appear also under nice

discrimination. Thus much in the meantime by way of praise. Now for

fault-finding. I differ from you entirely as to that going down upon his

knees in the House of Lords, which in my mind was a bit of the most

wretched melodramatic ever enacted—only, not just so bad as Burke’s

dagger. Ay, think of a man like Burke actually with malice prepense

getting the dagger—probably buying it—for the purpose, stowing it away

in his breast, and arranging all his speech to get the flinging down

done at the proper time! Pitiful trash of a trick!’’

16th May 1842.—Dr Cook, our Moderate leader, has been in this quarter,

and I have seen him once or twice. He is a kindly and dear old man—not

at all what you would suppose him. Fonder of his grandchildren, I assure

you (for his only daughter is married at Loch-maben), than of the

battles of the Kirk. He is a most lovable old man, and what a gentleman

withal!”

“22d April 1843.—I have been sauntering for some time reading Alfred

Tennyson’s poems, and other light matters. Alfred's brother lent me his

poems. Beautiful they are certainly, strong and manly often, but oftener

capricious, silly, and affected. ‘Codiva’was a most difficult affair

certainly, yet treated with what perfect grace and beauty ! Reserving

June for my visit to Bowden and Dundee (probably), I give you all the

rest of the summer to choose your time for visiting our valley.

My only condition is, that you are not to stay with me less than a

month. So, make your arrangements as you please. Pray write me again,

and don’t forget to tell me how poor Nicol is. Also let me know of

Brown.”

“12th June 1843.—Your letter from Old Comrie was unexpected, and

therefore the more pleasing. But in the name of kitty wren and hawthorn

blossom, why can’t you enjoy the green society of nature, and the simple

quiet of our ‘Old Scottish Village,’ without desiderating a set of

sympathetic chaps about you, effervescing or intense? Would I had old

Bowden for four or five months in the year, on the dullest terms you

could name. It has not yet got beyond thinking all ‘these writing chaps’

little better than a crew of good-for-nothing ne’er-do-weels, and I hope

never will.

I think you take a right view of the whole matter, in wishing to be very

very reasonable about that affair of the sermon. And pray reinforce your

manly intention with this consideration : Your Associate Body is shaken

just now with speculative innovations of opinion ; therefore be not

angry that it is more than usually jealous about all freedoms, even in

the degree of your own. Bear with it accordingly. . . . There is much

pedantry in the formulas of all Churches ; but it is not a safe thing to

let them be transgressed. Your duty is clear, accordingly ; and pray

don’t talk of ‘victimisation,’ ‘personal enemies,’ and so forth. There

can be nothing of the kind ever towards you by any that know you. When I

first saw your clear, open, candid face, ‘ There’s a heroic chap,’ said

I to myself—‘there’s a magnanimous chap, who will communicate strength

and sweetness to the life of all round about him.’ Such, I am certain,

is the true function of your goodly nature. . . . Depend upon it, you

have no personal enemies: no man would have one like you be a victim. I

beg of you to let me know the end of the matter. I could quarrel with

you also about the state of the country, but I have chid enough for one

letter. The sun has not done a right day’s work for the last month, but

the fellow has not lost his faculty, for here he is out to-day. Neither

has Great Britain : the present clouds are nothing to what she has come

through. She will yet ‘shine and save’—God bless her!—and make us all

(her much-endowed, much-blessed sons) ever hopefully, fearlessly,

determinedly thankful.”

“11 August 1844.—I would not care a fig for Jeffrey, not having seen

your MSS. You have seen already, from the failure of - and to serve you,

that booksellers will persist in taking their own way. Try a few of them

fairly, and if you don’t succeed, keep your MSS. snug in your bureau

till some future time. Meantime and always, our happiness must mainly

depend on our own self-contained consciousness of doing the practical

duty of our respective stations. Dr Carlyle is here just now. He has

some thought of visiting Mr Erskine of Linlathen, and, if so, will see

you. I go to Ayr on Monday, but care little about it. It is not in my

way at all. If you have a vacant hour this autumn, pray give me a little

‘Twaddle on Tweedside.”’

“23d September 1846.—I have just read Landreths’ review of ‘Pollok’ in

Hogg’s last number. He has done it well—very ; and is evidently a clever

fellow. I shall be very happy to have your notice of him for our next

paper. What profession is he of? I trust (according to Sir Walter’s

distinction of terms) literature is his crutch, not his staff.

“I have got back from Moffat, and am jog-trotting in as usual,

ruminating somewhat, but doing nothing. I have characters and incidents

for a romantic drama; but the plan is too scattered somehow, and does

not exactly please me. ... I missed Carlyle when I was away at Moffat.

He could sleep none in Scotland, and fled back to London, where he has

done nothing but sleep. How I sympathise with him ! ”

“12th August 1848.—What a glorious 12th of August ! Would I were with

you among the heather—unclerical Mantons apart! It seems a passion with

every Scotchman to dip his foot among the blooms. left Dumfries greatly

pleased with his reception here. His poetry is very juvenile and thin ;

but there is mettle in that face and head of his, and I think he will

make a good preacher. But, oh, what Lenten ware it must be at best

without the Incarnation of Deity! Since God put the faculties of

Shakespeare and all his affections in a piece of clay, it is not

wonderful to me that He has taken our nature upon Him, to hold kindly

intercourse with the noble creatures whom fie has thus fashioned. It

would be more wonderful to me otherwise. Oh the dry, mar-rowless bones

of Socinianism ! Pray write me now and tell me how Mrs Gilfillan is, and

how you are yourself, and what doing. You have heard, of course, of

James’s intended marriage. The youngsters are leaving me stranded high

and dry—

‘Here a sheer hulk lies poor Tom Bowling.’

“18th Nov. 1848.— I had also this week a right hearty letter from

Carlyle. He had marched into the bowels of my volume, and is much

pleased. This praise is acceptable to me. I will show you the

encouraging letter some future day. .

“You don’t know Samuel Fergusson of Dublin? I sent him a copy of my

book; but it had not reached him when he wrote me the other day. He has

succeeded, as counsel, in getting Williams of the ‘Tribune’ off; and I

trust it will be a shoeing-horn to draw on gowden shoes. He has got

married, and must work hard at the law; but Themis has not won his heart

yet. He is determined still to have a dash at poetry. He is a fellow of

rare powers, and I expect great things from him. . . .

“If, in your meditations dealing with the hearts of matters, any theme

of deep tragic interest strikes you, pray let me know of it. I fear I am

not the [man] now to execute much; but I have notions yet of new walks

in the drama on high mountain-tops. Life is too short for us, and it is

sorely nibbled away by small cares; yet well for us, perhaps. Work away,

and sing courageously as you work.”

“1st January 1849.—Cholera is almost off from us now; but we have

already lost one in thirty of our population—a rate of mortality which

would be equivalent to 10,000 in such a city as Glasgow; so you see how

mild the visitation is there, compared with the stroke on our poor

devoted town.”

“1st Feb. 1849.— I have just had an hour with Gordon, the inspector of

schools. He tells me that ‘ The Caxtons’in ‘Blackwood’ is by Bulwer

Lytton. Can it be possible? No piece of modern writing has charmed me

more. Can Sir B. L. really do such things? W. E. Aytoun is to be married

to Professor Wilson’s third and last daughter, Jane. All this is

building him round with new life, and yet it is leaving him lonelier

too. The death of a betrothed maiden is to me peculiarly affecting. With

what profound and beautiful pathos do the old Greeks lament it in their

inscriptions and other anthology. No wonder! How exquisitely applicable

Virgil’s words in such a case—

‘Sed dura; rapit inclementia mortis’!

Oh the force of that sed! Poor Robert - will need all the consolation

you can give him. Peace and good be with him and all of you.”

“7th July 1849.—Dear Friend,—I am grieved to hear of Mrs Gilfillan’s

serious illness, and the severe accident which has befallen yourself. To

both of you I send my earnest wishes for your speedy, complete

restoration. Rest completely, if you possibly can, from all work for a

month or so, and the bruise will have the less irritability to feed it,

and will pass off all the sooner. Your mind, moreover, will be freshened

by the pause. Keep in view that you have been working hard for a series

of years : see that you don’t press the fine springs too much. . . I

agree with you to a hair about the ‘Northern Days.’ The old fun will

never more be forthcoming, but the series may be made to embody much

high eloquence, taking in all the best part of the lectures. When this

is done, he should stop for ever, and gather up and arrange (adding and

eking) all the spolia opima of his genius which are lying scattered

about. I reread lately his ‘Unimore.’ Do but read it again for yourself.

What mines of matter in it ! I have just finished reading over once more

the morsels of criticism ’in Campbell's specimens. There is a want of

generosity about them ; but some of them are exquisite. To Collins, for

instance, he ascribes a ‘rich economy of expression haloed with

thought’—isn’t it fine? I have spent some pleasing hours this week with

Dr John Carlyle. He is well, and full of pleasant talk. Thomas is

expected in Scotland this autumn."

“25th July 1850. — Your letter is dew to my dull, dry time. Many thanks.

On you I can always count.

. . . This gnarled, snarled Bulldog of the North,

who has had a deadly grip of my sinews for the last three months, is

slackening his fangs in the sun, and I am now hirpling tolerably by our

river-side ; but I have not heard the cuckoo this year. If my

locomotives go on improving slowly, I still look forward to seeing you

about the end of August, if not the middle.

“Tell Yendys, when next you write to him, the severe rheumatic

obstruction which has kept me from acknowledging his last kind

communication, and give him my best regards. He is a very fine fellow. I

was puzzled about the authorship of that paper of his in the

'Palladium.’ I could think of nobody but Brown, and yet could not

satisfy myself that Brown it was. I presume the paper on Carlyle was by

the editor himself, Wight, sharp and clever enough, but devoid of the

rich inner man. You know what I mean.

“You naturally think the articles on Moffat are by myself. Not so. They

are writen by my friend Grierson, the minister of Kirkbean, one of the

greatest mountain-climbers of the age.

“I rejoice to hear of your literary progress and success; but I reserve

it all for our rest under the pear-tree of Paradise.”

“21st Dec. 1850.—My dear Friend,— . . . Certain things should never be

named, even for condemnation. That Byronism [Byron’s ‘ bit of blasphemy

’] about ‘Carnage’ is precisely such a thing. Why not let it sink out of

sight to Tartarus ? Why immortalise it in heavenly

‘Amber and colours of the showery arch’?”

“3d July 1S51.—Some little family adjustments call me over to

Roxburghshire in the end of this month, so I have been obliged to

postpone my visit to Dundee. . . . I trust you will enjoy your trip to

London, and enrich your mind with a hundred suggestive points. In that

nidits they won’t be long in ripening. Our summer here is now beautiful

; but to me a shadow is in it from the deplorable illness of my friend

and neighbour, Archie Hamilton. His heart is extensively diseased, and

cannot send the blood with sufficient force through his large body. A

deposit of water is the consequence, and it will drown him ere long. How

he does labour for breath in the flood!”

Mr Hamilton was a solicitor in Dumfries and an elder of the Church,

conspicuous for his portly presence and genial character. At his death

he bequeathed a large Bible to Mr Aird, who records the gift on the

opening page in these words: “My friend Archibald Hamilton died on 4th

August 1851, and this Bible came into my possession accordingly. Our

blessed Lord help me to read it with profit.”

2d Oct. 1S51.—A curse on magazine writing, which looks to the present

and forgets futurity ! I am just about to begin a short memoir. Could

you kindly send me what letters you had from Moir, that I may make a

discreet use of them? I had a day of Carlyle lately. He is well.

Browning and he are off to France. He gave me a private reading of his ‘

Sterling.’ It is very able and interesting; but it might have been as

well to let the poor forlorn ‘sheet-lightning’ die away in its cloud.’’

"25th January 1852.—When was I in such arrears with you before? But I

have been kept depressed and reluctant to work with this painful

affection of my heart. Delta’s proofs are still coming upon me; and I

have been in constant intercourse with the Crichton Institution for some

weeks, in consequence of the terrible seizures of a poor friend of mine

there, and the visits of his Edinburgh relatives. All this, with my

usual weekly work, has been quite enough for me. My brother James told

me of you the other day. I am specially thankful to hear that Mrs

Gilfillan is so well now. Spring will be upon us immediately, and dibble

and hoe in her eident hand. And you, G. G., down with your pen and out

to the ‘ paidle’ an hour every morning and evening. ... I share your

zeal about Croly. Poor fellow ! I am sorry to hear he is in very bad

health. Lockhart, also, has been very unwell. The ‘Critic,’ I am afraid,

wants body and substance. The last No. is exceedingly poor. That

alms-basket of critical scraps won’t do. Tell me, when you write, not

only of yourself, but of Dobell and all the worthies. Tennyson, I am

told, has a large poem on hand. I have a little piece in the forthcoming

‘Blackwood.’ ‘A simple thing, but mine own,’ quod Touchstone. We have

been drowned with floods; but I expect to hear the laverock tomorrow.”

“17th January 1854.—Your account of the Stirling meeting tickled me

greatly. I have ordered a copy of the ‘Eclectic.’ My interest in Wilson,

and my affection for him, deepen as his life runs low. . . . Give my

kind regards to Yendys when you see him. Balder is not yet The Poem. He

has been sowing bolls of pearls and ‘bags of fiery opals’ in the desert

of Sahara. I am provoked at a chap of such powers not knowing better."

“1st April 1856.— I have just received your note. Many thanks for all

your great kindness. In the continued exercise of it, do not fail to see

my brother James as often as you can, and cheer him up, poor fellow! . .

. I have had a very severe go of sore throat and bronchitis, and am

still mainly confined to the house. Oh for ‘ the dew-dropping south ’ !

Sarah and her little body were to have been with me on Monday; but she,

too, has influenza.

“Amidst all my snivelling, I have exchanged kind notes with Kingsley,

and David Masson, and Dr Waller of Dublin ; and long friendly letters

with James Hannay (who is a very rising chap, and will lend lustre to

good old Dumfries), and Professor Blackie, and Sarnuel Ferguson—author

of ‘The Forging of the Anchor,’and a man who had it in him to be the

greatest poet of the time. Our own Samuel, too—dear Brown—dictated for

me a short and affectionate note. I hope Mrs Gilfillan is not suffering

from this intergrilling, interchilling of summer and winter in one.”

“25th August 1856.—My dear Friend,—Cats and hens have carried the day,

or rather the night, against me, and I am off to Mountain Hall, a villa

not far from Dr Browne’s upper gate. I flitted on Saturday : a pony-cart

carried my whole gear—the gatherings of twenty-one years—so my organ of

acquisitiveness cannot be very large. My Tusculum is a charming one in

fine weather; but in winter it will be dull, I fear, and rather

inconvenient for me. I must just do the best I can. Would I were nearer

you ! The Rev. Arthur P. Stanley, the biographer of Arnold, with two

young Oxonians, was here on Friday. They brought a note of introduction