|

IT was not in Agriculture alone that the great

principle of giving free scope to individual Mind, and to individual

Capital, which is its fruit, became the prime agent in the advancing

prosperity of Scotland. It was equally conspicuous and equally powerful in

the opening of her Trade and Commerce. In a former chapter' I have referred

to the engrossing Monopolies which had been given by early Charters to the

old Royal Burghs of the country. Those who have been accustomed to think of

Fiscal Protection as specially associated with the interest of Landowners,

have little idea how universally this system originated with the only

popular Bodies which existed in the Military Ages, or of the extravagant

lengths to which commercial exclusiveness was earned on their behalf. For

centuries, and by repeated Statutes, the whole Trade and Commerce of

Scotland were placed in the hands of a few Communities of ancient date, to

the absolute exclusion not only of the whole agricultural classes, but to

the exclusion also of all other Towns and Villages which had arisen from

time to time in situations favourable for some particular kind of industry.

The "liberties" granted to the old Communities were Monopolies in the only

correct sense of that word—the sense, namely, in which it means the absolute

prohibition of all selling and buying by all persons who do not belong to

the privileged Community, so that even their own money and their own goods

are made useless for purposes of exchange except through the narrow circle

of the Monopolists.' Not a single quarter of corn,—not a single beast of any

kind,—not a single cask of wine,—not a single fleece of wool, nor hide of

cattle, could be lawfully imported, or even bought and sold, except through

the hands of the privileged Freemen of the Royal Burghs. Within the Burghs

themselves the Magistrates assumed and exercised the right of regulating and

fixing the prices of all kinds of goods, and especially of bread and

provisions generally. This was done in the assumed interest of the

Community.

Nothing is more remarkable in the History of Scotland

than the manner in which this wide, deeply rooted, and oppressive system was

gradually invaded and destroyed by the natural action of individual

interests, without any previous change of abstract opinion against the

general policy on which the system had been ignorantly founded. So late as

the reign of Charles II. in 1633, a fresh Act was passed renewing, reviving,

and enforcing the older Statutes, and whatever had become more or less

obsolete in these Communal Monopolies over the whole Trade and Commerce of

the Nation.' This was too much. There was an immediate and strong reaction

from the growing energies of individual enterprise and industry. The first

great breach which was effected in the system, came through the undermining

action of the new Towns and Villages which had no old Charters, and were not

included within the charmed circle of the Royal Burghs. The inhabitants of

these places could not practically be prevented from buying and selling such

articles as they were able to make, or—if they were near the sea—to import.

Then came the supporting action of the Landowners on whose Estates these new

Town were rising. They had risen and were growing under the powers and

rights of Leasing, of Feuing, and of Heritable Jurisdiction, which these

Landowners held by Charters erecting their Estates into Baronies of

Regality, or into simple Baronies with powers only a little less extensive.

Hence these new Towns and Communities were called Burghs of Barony and of

Regality. For several centuries there had been more or less of a perpetual

struggle on the part of the Royal Burghs to enforce their monopoly, and to

crush the newer Towns as nests of Smugglers. On the other hand the great

Landowners who held Baronies and Regalities, were naturally interested in

the prosperity of the new Towns which were rising under them, and thus

became insensibly, but very practically, interested in the extension of

individual liberty, and consequently in the freedom of Trade. Accordingly

when legal questions arose, and the Royal Burghs prosecuted other Towns for

violation of their monopolies, the Landowners sometimes appeared in support

of the defence.

The Act of 1633 was too violent to be borne. At last,

in 1671, a case arose which brought matters to a head. Falkirk was a Burgh

of Regality built on the Estate of the Earl of Callendar. But it was within

the area of Monopoly claimed by the Royal Burgh of Stirling. It was

prosecuted for allowing its inhabitants, who were "unfreemen," to engage in

trade. The case attracted great attention. The Barons of Regality took up

arms in a body in favour of a wider liberty. The Duke of Lauderdale himself,

who was interested in the rising Town of Musselburgh, was induced to come to

Edinburgh to watch the case as it was argued before the Court of Session. It

soon appeared that the questions raised touched the whole policy of the

Kingdom, and could only be settled by the Legislature itself. A suggestion

to this effect by Sir George Mackenzie was taken up by the Lords of

Parliament, whose duty it was to prepare Bills; and the result was the Act

of 1672,' which effected a temporary compromise between the interests of

individual freedom and the old Monopolies in the hands of a few popular

Bodies. Parliament declared that the Act of 1633 had extended those

monopolies to a degree "highly prejudicial to the common interest and good

of the Kingdom." Nevertheless, the monopoly of the Royal Burghs was for the

future kept up as regarded both the export and import of many articles of

foreign produce, except in so far as private persons of all ranks might

import them for their own domestic use alone. On the other hand, the export

and sale of all agricultural produce and all native commodities was made

free to all the subjects of the Realm. The new Towns, the Burghs of Regality

and of Barony, were made free to trade in all manufactures of their own, to

export all home produce, and to import many articles required for "tillage

or building;" whilst the retail trade of Markets was made absolutely free.

This was a tremendous breach in the exclusive

privileges of the old Burghal Communities, and it was the opening of a very

wide door for the free action of all individual interests. Accordingly,

against the ever widening consequences of this Act the Royal Burghs, which

alone were represented in Parliament, carried on an unceasing struggle and

protest, loudly calling for its repeal. They did succeed in getting some new

Acts passed after the Revolution, fencing and guarding, by new provisions

and penalties, the exclusive rights which still remained to them as regards

the imports of foreign produce; and at a later date their interest in

Parliament, backed by the influence of traditional feelings and opinions

which were not yet theoretically abandoned, were sufficiently strong to

secure a Clause in the Treaty of Union with England, providing for the

security and continuance of their privileges as they then stood. But too

much freedom had now been granted to keep out the continued and unceasing

pressure of individual Mind. The Courts of Law in all doubtful cases ruled

in favour of freedom in the true sense of that word, the sense, namely, of

individual liberty. The natural right Of every man to exercise his own

faculties in the free disposal of his own means and property, became too

wide an instinct to be compatible with even a faint survival of the

Communist Monopolies. Yet it may well be regarded with surprise, that, so

far as the Statute-Book was concerned, they survived down to our own day. It

was not until 1846 that an Act was passed formally abolishing them, and this

was passed as the resuif of an inquiry by Royal Commission, which reported

that practically they were already dead.

Every step in the long process of self-education

through which the Nation passed in this question of Trade Monopolies, is

full of historical and of political interest. There are two documents which

throw especial light upon that process, which are separate from each other

in date by no more than 35 years. The first belongs to the time of the

Commonwealth—the second belongs to the time of William in. The Protector, as

is well known, contemplated and for a time effected, a complete Union

between England and Scotland, both being under one Government, and

represented in one United Parliament. It is to the credit of the Royal

Burghs of Scotland that a majority of them seem to have voted for Cromwell's

policy, which included as one of its main advantages, complete freedom of

commercial intercourse between all citizens of the Commonwealth. Struck by

the poverty of Scotland and the heavy deficit on its revenue below the cost

of its administration, he sent down an experienced Coiimissioner' to inquire

into the subject, and especially into the condition of the Royal Burghs. His

Report, rendered in 1656, gives an authentic and a very striking account of

the almost abject poverty of the country, and of the miserable narrowness of

its Commerce. He saw at once that much of this scantiness of Trade was

directly connected with the backwardness of Agriculture, and the consequent

want of any products to exchange. This condition of Agriculture again he

ascribed to the ignorance, poverty, and slothfulness of the people. With a

curious insight and perspicacity, he pitched on the most striking symbol of

all the waste he saw, and pointed to a "lazy vagrancy of attending and

following their herds up and down in their pasturage."' There was

consequently no trade from the inland parts. There never had been much ; but

what remained was limited to the seaside, and was confined to a few Ports on

the East coast, and in or near the Estuary of the Clyde. Glasgow had then

only twelve vessels, the biggest of which was 150 tons burden, and most of

which were mere boats. They traded to Ireland with small coals in open boats

of from four to twenty tons, taking back meal, oats, butter, with barrel

staves and hoops. There was a limited trade with France and Norway—coals,

plaiding, salt herring, and salmon being the chief articles, for which they

got some condiments and prunes. Dundee had suffered severely from the Wars.

Her trade had declined, but "though not glorious, yet was not contemptible."

She had ten vessels in all, the biggest 120 tons. Ayr was in a sad

condition, from the silting up of her river and harbour. "The place was

growing every day worse and worse." Newark (now Port-Glasgow) had "some four

or five houses besides the Laird's house of the place." Greenock was just

such another, only a little larger —the people all fishermen and sailors

trading to Ireland and the Isles in open boats; yet in spite of all this

leanness in the land, Cromwell's agent had the perception to see, and did

not omit to mention the "Mercantile genius" of the people.

Such was the description of a stranger, coming from a

wealthier country in 1656. But thirty-five years later we have the

description of the Royal Burghs of Scotland given by themselves. They had

spent many of the -intervening years in vain endeavours to enforce their

monopoly against all their countrymen, and in alternate contests and

negotiations with the Landowners who were encouraging the new, unprivileged,

individual Traders who were rising everywhere. The Restoration of the

Monarchy had brought with it the immediate abandonment and revocation of all

Cromwell's policy, including Free Trade with England. This great outlet was

lost to Scotland—to all her Towns whether "free" or "unfree." All the more

was personal energy and character required for success in the narrowed and

restricted paths of industry. The old Royal Burghs did not advance. At last,

in 1691, they appointed a Committee to inquire and report on the condition,

revenues, resources, and difficulties of every one. A tabulated series of

questions was addressed to each. The result was a series of Reports of the

highest interest in History and in Politics. One broad result stares us in

the face—that almost everywhere the privileged and monopolist Burghs were

stagnant or declining, whilst the new Towns which had no privileges, and

were even heavily handicapped in the race by having to fight against

Communal Monopolies, were as universally prosperous, and were rising every

year in wealth and in importance. Mind, set upon is mettle, was everywhere

triumphing over routine and usage:—Mind, in the selection of new sites—Mind,

in the advantage taken of special opportunities—Mind, in seeing new

openings—and everywhere, Mind freed from the stupid levelling of arbitrary

Guilds.

Nothing can be more striking than the evidence to this

effect. One of the questions asked of all the old Royal Burghs concerned the

number and condition of the New Towns of Barony and Regality which existed

within the area of their Monopoly. The list given is a list of many of the

most important Towns now existing in Scotland. The Royal Burgh of Renfrew

enumerates no less than nine new Burghs of Barony and Regality within "their

precincts," even the smallest of which had "a much more considerable trade"

than themselves. Among these nine we find Paisley, Port- Glasgow, Greenock,

and Gourock. The rising trade of all these places was, if possible, to be

suppressed, and the Royal Burghs universally refer to it as "highly

prejudicial" to their own interests and industry. Even Glasgow was at that

time declining—with nearly five hundred houses "waste," whilst those still

inhabited had fallen nearly one-third in the rents they fetched. The best

houses in Glasgow were at that time worth no more than £8, 6s. a year in

Sterling money. Glasgow bitterly complained of the same neighbouring Towns,

and of some others, which so vexed the soul of Renfrew. In particular, the

little village which was growing up on the shores of "Sir John Shaw's little

Bay," Greenock, was described as having "a very great trade both foreign and

inland, particularly prejudicial to the trade of Glasgow."

And yet in the midst of these stupidities we have a

few evidences that even the Communal Mind was opening to the lessons of

experience. In a few cases men began to see that the action of the human

Will is subject to certain natural laws, and that when enactments run

counter to these, or do not take due note of them, such enactments, however

virtuous in motive, are purely mischievous. Thus in 1688, the Convention of

Royal Burghs had awakened to the fact that the Sumptuary Laws had been "very

prejudicial" to them.' It was turning out that what were called the luxuries

of the rich were inseparable from the comforts and necessities of the poor.

Costly things were only costly because they were much desired, and because

much was consequently given to those who could find, produce, or make them.

And a great part of this cost went of necessity to the Muscular Labour,

which was the contribution of the poor. Again, the Royal Burghs were

beginning to find out that even within their own "precincts," individual

enterprise was breaking through the incubus of their communal restrictions.

Individual citizens and Burgesses, seeing the success of their neighbours in

the "unfree " Towns, were entering into partnership with them in various

enterprises and speculations. It is worth while to listen for a moment to

the words in which this conduct of men in the free disposal of their own

faculties, and of their own property, was denounced by that spirit of

tyranny which is never more oppressive than when it is wielded in the

supposed interest of a local popular majority. "The Convention being

resolved no longer to suffer the privileges of Royal Burghs to be abused and

encroached upon by their own Burgesses, who, by joining stocks with

unfreemen, inhabitants in the Burghs of Regality and Barony, and other

unfree places, both in point of trade and shipping, whereby those unfreemen

receive all imaginable encouragement from freemen in Royal Burghs to trade,

and that the said freemen do voluntarily and with their own hands destroy

the privileges of the Royal Burghs —therefore" the Convention denounced new

pains and penalties against all such persons—as disloyal to the Community to

which they belonged.

Here was an aperture in the armour of Burghal

monopolies which the irrepressible energies of individual interests were

quite sure to widen. Partnerships could be easily concealed, and the only

result of enforcing inquisi.ion into the use to which men might put their

own money, would have been, and doubtless was, that the most enterprising

Minds would seek refuge in the new Towns. With them, therefore, the contest

was hopeless, and it soon ceased altogether. But for many years after this

date, and even after the Union, the exclusiveness of the Guilds in the

supposed interest of the Skilled Labour, and of the Retail Trade of the old

Burghs, continued unabated. It was reserved for this system as it prevailed

in Glasgow, to afford the most signal illustration of its antagonism to the

laws of Nature. The site of Glasgow had been chosen without any view to

industry even of the earliest and rudest kind. It had not clustered under a

Rock Fortress, like Stirling or Dumbarton. It had not arisen beside a

natural harbour, like Dundee or Aberdeen. It had not grown up out of a

fishing-village, like Greenock or Rothesay. Its nucleus was not even a

feudal Castle. Its position had been determined by the Cathedral of St.

Mungo, and was originally a mere hamlet of " the Bishop's men" living under

the protection of a great Archiepiscopal See. It was not among the number of

the most Ancient Royal Burghs of the Kingdom. In the Fifteenth Century its

importance was increased by being made the seat of a new University. But

this was done through the same influence and agency of the Church to which

the Town owed its own foundation. Glasgow was itself, therefore, nothing

more than one of the Burghs of Barony on a Church Estate. Two of the Old

Royal Burghs, Rutherglen and Dumbarton, long domineered over it, as now

Glasgow tried to domineer over Greenock and Paisley. It is true that it

stood near the river Clyde, towards which its houses gradually straggled.

But the Clyde at that point was distant from the sea, its course was very

shallow, and it was being perpetually silted up with shifting sandbanks.

This was one of the causes of its decay in Cromwell's time. Only through the

new openings which came with the Union did it begin to revive again. But, as

a Seaport, it never could have reached its present position without the

operation of the Steam Dredge, through which ships of the heaviest burden

have long been able to ascend the river, and to lie beside its quays. During

the last forty-six years very nearly forty millions of tons of material have

been removed from the bed of the Clyde by the Steam Dredge—a mass which

would form a conical mountain 513 feet high, with a circumference at the

base of one mile and a half.' Yet it is a memorable fact that when the

future Inventor of the new Steam Engine, without which dredging on this

gigantic scale would have been impossible, came to reside and to open a shop

in Glasgow, he was persecuted as an interloper and a poacher on the domain

of the Guild of Hammermen. James Watt was then probably known there as an

ingenious Mechanic, but he must have also been known as the grandson of one

of the earliest Bailies of the "unfree" Town of Greenock, that most

presumptuous union of the villages of the Crawfords and the Shaws. The

Hammerrnen declared that from the competition of such an "unfree-man," the

whole Community would "suffer skaith." A man on whom Nature had bestowed, in

richer measure than it had ever been bestowed before, the very individual

and the very special gift of mechanical genius, and whose discoveries were

destined to raise Glasgow to be one of the greatest Cities of the world, was

actually driven from her Burghal "precincts." Fortunately the University had

precincts of its own which were outside the "liberties "of the Guilds.

Within that sanctum this patient and laborious Mind wrought out the great

problem on which its heart, as well as its intellect, was set. It thought

and pondered, and weighed and measured, and tried and tried again, until at

last the moment of Inspiration came, and one of the most tremendous agencies

in the material world became tractable as a little child. It was tamed,

yoked, and bound to every variety of human service —an immense contribution

indeed, not only to the Common Good of Glasgow, but to the Common Good of

all Mankind.

The same natural play of instinct and of motive which

had led the Landowners with such immense success to foster individual

liberty and enterprise, in the hands of their own Villagers and Feuars, now

led them also to rely more and more on the same great principle as equally

applicable to their agricultural Tenants. For this purpose the first step to

be taken was that, wherever possible, on the expiry of old Leases, their

farms should be re-let to individual Tenants. Such Tenants became at once

freed from the trammels of Communal Usage, and could move out of the ruts in

which the wheels of progress were jammed up to the very axletrees. They

could —but were they sure to do so? Here again there was an education of

experience—analogous to that which only very slowly and very gradually

educated the Towns in the lessons of the new Industrial Age. It soon turned

out that neither the mere circumstance of undivided holdings, the additional

circumstance of very long Leases, were enough of themselves to secure an

improving Agriculture. The reason is obvious. If the sources of all Wealth

are Mind, Materials, and Opportunity, it is clearly not enough to have only

one, or only two of these sources opened. Materials are useless, and so is

Opportunity, and so are both together, if the appropriate qualities of Mind

to make use of them are wanting. Significant indications are given in the

Reports so often referred to, of the steps of experience through which the

Owners of land were taught how best to secure the improvement of the soil.

Thus in the Lennox, the perpetual tenure of Feu for a fixed annual payment,

had been given over various areas of agricultural land to men who thereby

became small Owners, and had all the inducements to improvement which

Ownership is reputed to give. But neither the accumulations due to Mind in

the past, nor those aspirations of Mind which regard the future, were

present to take due advantage of the Material and of the Opportunity. These

Feuars belonged originally to the old unimproving class. They had no

conception of educating their children for any other employment than that on

which they and their fathers had maintained existence. Consequently they

went on sub-dividing their lands among a progeny as ignorant and unimproving

as themselves. "They thought it a disgrace that their children should be

anything but Lairds." This sub-division went on increasing until the little

possessions had become so small, in 1794, that some of the Owners could not

afford to keep a horse. Then we have the usual sickening detail of constant

over-cropping, of "nothing being laid out on improvements, and of the land

being scourged to the last extremity." The whole produce could hardly

support the families that depended upon it, even with the addition of what

was procured by the unremitting labour of the wife and children in spinning

and a little weaving? This is an exact description of the results of a

similar condition of things now common among the Peasant Proprietors of

parts of France, as described by such eye-witnesses as Mr. Hamerton, Lady

Verney, and many others.

The lesson against feuing agricultural hand was hardly

needed. Land feued is land sold. Feuing is merely one form of total

alienation. A "Superior" parts with all the powers and rights of Ownership,

except that of receiving a Rent charge. The Feuar becomes the Proprietor. On

the other hand, the evidence furnished by the Report of 1794 on

Dumbartonshire, is in favour of what are now called Allotments—that is to

say, small areas of land let to Labourers and Tradesmen who were

intelligent. These were reported to be by no means ill cultivated or

unimproved.' On the contrary, they were reported to be as far advanced as

any part of the County—at a time too, when the Common Good of the Burgh was

lying comparatively waste. On such Allotments the full benefit of individual

interest was at work, coupled often with knowledge above the average of that

possessed by the old class of Tenants. Feus are an excellent tenure for

purposes of Building, and Scotchmen generally will not build on any tenure

less secure and permanent. But there is no reason which should induce a

Proprietor to give off agricultural land on this tenure. If he wishes to

sell, it is best to sell out and out. But the example of those old feus to

small Owners in Dumbartonshire is an excellent illustration of the general

principle on which all improvements depend.

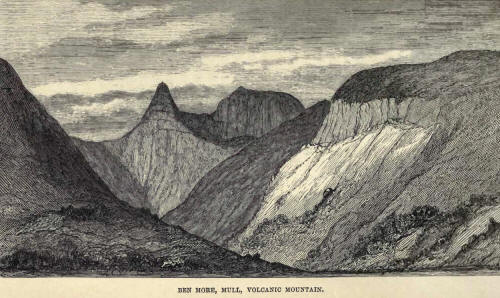

There was, however, another case in which the

teachings of experience were more practically important. Leases of great

length are another panacea amongst those who have had no experience, which

is often recommended with much confidence. But this also was tried, and with

the same result, depending exactly on the same principles. It appears from

Professor Walker's Work, published in 1808, that Archibald, third Duke of

Argyll, the friend of Culloden, had been induced to give some very long

Leases of large farms in Mull—Leases for "three nineteens," or a period of

fifty-seven years. He expected the Tenants to set a pattern of industry and

improvement" on such length and security of tenure. But the expectation was

not fulfilled. When the Leases were half expired the farms were found to be

as little improved as any on the Island. The same experiment had been tried

in the Island of Islay by Mr. Campbell of Shawfield, who, in 1720, let all

his Estate on Leases of the same long duration, with the result that in 1764

that Island had undergone no improvement—with one solitary exception. Flax

had been introduced, and became a, source of industry and advantage to the

Island. But this one exception was the result, not of the long Leases, but

of the only compulsory clause which had been inserted in them by the

Proprietor, which was a clause binding the Tenants to cultivate flax.' It

thus appeared that the only one item of improvement which had been effected

during more than half a century was due, not to the Mind of the Tenant, but

to the Mind of the Proprietor— to his forethought, and to his knowledge—in

binding men who were comparatively ignorant, to begin a new industry, which

of themselves they never would have thought of.

In this one exception to the general result we see the

whole secret and the whole philosophy of the only method by which it was

then possible to improve the agriculture of Scotland—to arrest the

increasing impoverishment of her soil, and to lift her rural population out

of the poverty and sloth in which they lived. It was the exercise, in a new

direction, of the same Power to which the Parliament of Scotland had often

appealed before, not only to secure a Tenantry loyal to the Government, but

also to secure such rural improvements as were then known. Educated men were

to direct the energies of men less instructed. Mind was to keep its power

over Muscle. Very long terms of Lease, during which this power was to be

suspended, could not but be mischievous. Most fortunately for the country,

few Proprietors had been induced to try an experiment which could not be

stopped during the long period of nearly sixty years—although it might be

quite evident before one-half that time had expired, that it must end in

total failure. In the great majority of cases they had granted no other

Leases than those of the ordinary duration of "one nineteen," and at the end

of every Lease they inserted stipulations in the new Tacks binding the

Tenants to execute certain specified improvements. These, of course,

expanded with the expanding knowledge of the day. Proprietors were

themselves only in course of being educated; and some were before others in

appreciating and accepting the advancing knowledge of a new science. In some

points they were almost as slow to break with ancient Usages, and to

perceive the mischief of them, as the most ignorant of their Tenants. The

heavy dues exacted for "Thirlage," or the maintenance of Mills, were a great

evil, and they were not wholly abolished till recent years. But the

stipulations in Leases became more and more enlightened and important in

their effects. They began generally with stipulations for the making of

enclosures, and for the building of better Houses than the old hovels, which

were as universal in the Lowlands as in the Highlands. But this rudimentary

step of providing for enclosures speedily involved corresponding

stipulations for the uses to which enclosed land was to be applied. There

were clauses to forbid old habits which were ruinous. There were clauses

prescribing new methods which were fruitful—clauses forbidding continuous

cropping with Cereals—clauses enjoining an alternation with the new Green

Crops—clauses insisting on the use of Sown Grasses—and on the application of

due quantities of manure. With the growing knowledge of the cultivating

class, and the yearly proofs experienced of increasing produce and of rising

values, the necessity for such detailed stipulations gradually abated. The

"rules of good husbandry" became a legal phrase, having a definite meaning,

and susceptible of judicial interpretation. A class of Tenant farmers arose

having themselves ample knowledge, sufficient capital, and technical skill.

In proportion as the permanent accommodation and apparatus required for

scientific agriculture became more costly, it became more and more the

universal habit in Scotland that the Owner should supply that accomrnodation

and apparatus along with the land itself. In some cases part of this work

was done by the Tenant on stipulated conditions—he making his own

calculations for repayment, either by comparative lowness of rent, or by

comparative length of Lease—or by both combined.

It is not often that we can enjoy in human affairs the

sharp and clear processes of demonstration which are the glorious reward of

Physical Research. Yet such—and not less certain—are the proofs now afforded

by the history of Scotland in favour of the Powers and Agencies through

which her Agriculture was reformed during the latter half of the Eighteenth

Century. By all that had happened before the change—by all that ceased to

happen wherever it was effected—by all that continued to happen wherever it

was hampered or delayed,—it is proved to demonstration that terrible evils

and dangers were inseparably bound up with the older system, and with the

ignorant habits in which the whole of it consisted. This is one kind of

proof. But there is another kind. By all the benefits which the change

immediately conferred—by all the increase in these benefits which arose in

proportion as it became developed—by all the sacrifice of them wherever it

was still delayed,—we can see without the shadow of a doubt, that the new

system was founded on Natural Laws, on the recognition which they demand,

and on the obedience which they reward. Nature takes no cognisance of

stupidity in the sense of allowance or of remission. She does take

cognisance of it in the way of punishment. Chronic poverty and frequent

famines had been, as we have seen, the punishment in Scotland of the

ignorant wastefulness of its traditionary agricultural customs. So now when

Mind had been awakened, and when its energies, wielded by individual men,

had been turned with better knowledge to the improvement of the soil, Nature

took notice of it by a lavish increase of her fruits. It is a striking fact

that the "iii years "—the bad seasons—of 1781-2 were the last which

afflicted any large part of Scotland with severe distress and the danger of

famine. In those years the new knowledge, and the new class of Tenants who

were able to make any use of it, were as yet established only in some parts

of the country. Everywhere else the old usages were still supreme—the Runrig

cultivation—the promiscuous grazing—the wretched Cattle—the not less

wretched Oats and Bear. The consequence was that over no less than fifteen

of the Counties of Scotland, a population of not less than 111,521 souls

were only rescued from starvation by charitable collections.' After this

date down to our own times there have been bad seasons again and again

recurring at about the usual intervals—but never have they had the same

effect—except in the few remaining fastnesses of the ancient ignorance.

These fastnesses have chiefly been in the Hebrides, and in a few Districts

of the Northern Highlands —always where, only where, and in proportion as,

the old stupidities have resisted and survived.

But the story of this resistance is so curious and so

instructive that it must be shortly told.

We have seen how in 1739, under the advice of

Culloden, the first great step had been taken on the Hebridean Estates of

the Argyll family—that of redeeming the class of Sub-Tenants from their

servitudes to the Tacksmen under whom they universally held at Will. In some

cases they were themselves raised to the position of Tacksrnen—in all cases

they were freed from indefinite exactions. We have seen, too, how shocked

Culloden had been by the wasteful and barbarous husbandry he witnessed in

Tyree. But on the other hand he did not see his way to any immediate or

compulsory change in these methods of cultivation. He probably thought that

self-interest, now called into play under new conditions of security, would

be enough to bring about reform. Wielding the powers of Ownership, he had

abolished one deeply-rooted and most ancient custom—the custom of indefinite

Servitudes. He did not know, or perfectly understand, that nothing but the

same powers, wielded with like determination and like intelligence, could

uproot those other Servitudes—as old and as destructive —under which the

people were chained and bound amongst each other in a perfect tangle of

obstructive usages.

Culloden and all that generation passed away, with his

two friends, Duke John and Duke Archibald (Lord Islay). The struggle was

unceasing to get the people to amend their culture. Then came the

Potato—then the Kelp. Subsistence became comparatively easy, and was

sometimes abundant. But all this came to a people unprepared by previous

habits, or by any new aspirations, to profit by it. Nothing was saved or

stored. They lived, and ate, and multiplied. From the date of my

Grandfather's succession in 1770, he issued ceaseless instructions for the

improvement of the people. He insisted in his Leases on enclosures, to save

the arable lands from constant invasion by whole herds of useless horses and

lean cattle. He insisted on better Houses. He tried his best to prevent the

systematic waste of Barley by illicit distillation. He tried to establish

Fisheries, lie tried to stop the destructive habit of breaking up pasture on

Sands which were liable to be blown. When Kelp became an important resource

he left so large a part of it to the workers that they held their land

practically for nothing, because the whole rent, and often much more, came

out of Kelp. His rent from 13,000 acres of land did not amount to more than

the saleable value of the Barley crop alone. All other produce,—potatoes,

lint, sheep, milk, butter and cheese, poultry, eggs, etc., were not counted

at all as contributing to rent, because the Proprietor said "he wished the

Tenants to live plentifully and happily." It was all in vain—as regards any

permanent improvement. Plenty is a relative term. Produce which was

plenteous for a population of 1676 persons in 1769, would not be plenteous

to a population which had risen to 2776 in 1802. In that year the condition

of the Island alarmed his agent, Mr. Maxwell of Aros, an excellent and able

man who was maternal grandfather of the late Dr. Norman Macleod. His Report

is a repetition of the worst accounts to the Board of Agriculture in 1794.

Subdivision had reduced the holdings to starvation point. The Cows did not

produce calves above once in two or three years. Troops of Horses, used only

for dragging seaweed at one time of the year, preyed all the rest of the

year on the exhausted pastures. Hosts of Cottars living only on the wages of

Kelp- burning oppressed the unfortunate Tenants. The quality of the Barley

was deteriorating rapidly. Ignorance of all husbandry, and stubborn

attachment to the old customs, offered "arduous obstacles to the improvement

of the Island." The additional One Thousand people who had grown up in

recent years could not be supported. Iy Grandfather had begun to entertain

the proposal to help them to the Colonies. But in 1803 there arose, as we

have seen, that panic against Emigration described before. The old Duke

seems to have deeply shared in it. His soldierly spirit was stirred, too, in

favour of the men who had enlisted in the Fencible Regiments which were

about to be disbanded at the Peace. He determined to try a new plan. He

resolved to break down and cut up several of the larger Farms falling out of

Lease, and to settle as many of the people as he could on smaller but

separate Holdings of a size calculated to support a Family with ease. But

one essential part of this scheme was enclosure —individual possession—the

abolition of promiscuous waste in the form of Runrig. He employed a

professional Surveyor to lay out the, new "Crofts," which were to be capable

of supporting not less than 16 Cows.

This most benevolent scheme was met by the most

obstinate resistance on the part of the people. Rather than give up the

wasteful habits of Runrig, they declared they would rather go to join the

emigration which Lord Selkirk was then leading to North America. The Duke's

agent at the time was a Highlander himself, intimate with the condition and

habits of the people. Yet he writes almost in despair with their infatuated

blindness to their own obvious interests, and to the value of the reforms

which had by that time become accepted by every educated man. He suggested

to the Duke a postponement of the plan. Yet time was needed to make even a

beginning, and the powers of Ownership were once more asserted to insist on

the abolition of a system so destructive and so dangerous. By firmness, and

by assistance given in fencing, the division and individuality of the arable

lands was at last effected. The grazings only continued to be used in

common, but even on these the amount of stock was carefully fixed and

apportioned to each man.

Now followed a most remarkable series of facts. The

old Field-Marshal died in 1806. In one respect his policy was entirely

successful. The separation of holdings—the individualisation of the arable

areas—resulted, almost automatically, in a great increase of produce. But it

had another result which was not foreseen. It facilitated and gave a new

impulse to further subdivision. Under the Runrig system the introduction of

an additional shareholder required assent. In settling this there were at

least some difficulties to be overcome in the way of subdivision. Under

separate holdings of the arable area these difficulties were much

diminished. Increasing produce and a greater freedom in subdividing, were at

once taken advantage of by a people whose intelligence was not developed in

proportion to its opportunities. Nothing but the continued exercise of the

powers of Ownership in fighting a watchful and uphill battle against

inveterate habits, could have been successful. Instead of this there was an

almost complete abandonment of all control. There came a Reign— not of Law,

or of Mind—but of what in medical language is called "Amentia." My

Grandfather's Successor' lived for thirty-three years—during the whole of

which time the powers of Ownership may be said to have been suspended. He

was a perfect type of the kind of Landowner who was adored in Ireland—one

who never meddled or interfered with the stupidities of Custom. Celtic

usages were allowed their course. Subdivision went on at a redoubled rate,

and population kept up even more than pace. In 1822 the Farms which had been

held by small Tenants ever since Culloden's time were crowded with a

population of 2869 souls; whilst the newly divided farms, five in number,

held no less than 1080 more. There had been a bad season in 1821. The Cattle

were almost starved, and there were many cases of great misery among the

people. Once more, Kelp came to the rescue. There was an extraordinary

supply of it, and this, with wholesale insolvency admitted and allowed,

tided over the crisis for a time. Next came another tremendous blow. The

whole Kelp Trade rested on Fiscal Protection, and on two special taxes

alone. One was upon Spanish Baril la—a Plant growing not in the sea, but on

the land, and rich in the Alkalis which seaweed afforded. The other impost

was the tax on Salt—a tax most oppressive to numberless industries, and

specially injurious to the Highlands, through the impediments thrown in the

way of the trade in fish. From common salt, which is a salt of Soda, the

same important Alkali could be made into other combinations. Both these

taxes were repealed—one in 1823, the other in 1826. The trade of the Kingdom

as a whole was immensely benefited. But the special, and the only

manufacture of the Hebrides, and of the adjacent coasts, was destroyed.

In all other countries when Mines are exhausted, or

when Mills are closed, or when any other local industry is extinguished, the

people who had been so employed invariably move off to other fields where

their labour can be made remunerative to themselves, and useful to the

world. But the Hebrideans never thought of this. There is, nevertheless, no

suspension of the laws of Nature for the special and exclusive protection of

any particular set of men, merely because they belong to a particular race,

or because they live in an Island, or because they speak a particular

language. Failing the Kelp trade, they still held on by the Potato. The

consequence was that the "ill years," which must every now and then recur,

always smote them with the misery and famine which had in former generations

smitten the rest of Scotland. In 1836-7 there was terrible misery all over

the Highlands wherever the old system still survived, and especially in

Skye. We have an account of it, and of the causes which produced it, from an

educated Highlander, who writes with that high intelligence of his race

which never fails to be conspicuous where-ever Highlanders are lifted above

the level of the old Paternal Customs. I need not repeat his story. It is a

mere duplicate of the course of events which we have followed in Tyree.

Everything that had been done in the panic of 1803 against emigration, had

simply ended in aggravating the evil. Even the making of the Caledonian

Canal, begun in the same year, from which much was hoped, had done no

permanent good. The Skye men had indeed worked at it. Whilst the

construction of it had lasted, between 300 and 400 of them had earned from

£3500 to £4000 in the half-year. But there was no change of habits—no

elevation in the standard of living. On the contrary, it was becoming lower

and lower from the wretched husbandry, and from the stimulated growth of

population. The one Parish of Kilmuir had in 1736 only 1230 souls. Even this

was far above the population it had supported in the Epoch of the Clans.

This is repeatedly and emphatically stated by Mr. Macgregor, and it reminds

us that even then the population of the old Military Ages had been far

exceeded. Yet nineteen years later, the population had risen to 1572. In

1791 it was 2060. In 1831 it was 3415, and in this year of renewed famine

1836-7, it amounted to about 4000.

It will be observed that this exorbitant increase went

on after the Kelp trade had been destroyed. There was nothing whatever to

justify, or account for such increase except an ever- increasing dependence

on the Potato, and a corresponding lowering of the conditions of life. There

vas not the slightest advance in agricultural knowledge or industry. On the

contrary —no account given by wandering Englishmen or by Low Countrymen,

which may be thought highly coloured by anti-Celtic prejudices, can exceed

in wretchedness the account by this descendant of the Clan Gregor in respect

to the industrial habits of the Skyemen among whom he lived so late as 1838.

The women alone did all the harrowing; whilst every implement and every

method of cultivation were alike barbarous and ineffective. Next came the

final blow—the Potato disease of 1846. By that time the population of Tyree

had increased to about 5000 souls—an increase probably without parallel in

any purely rural district in the world. It may bring this abnormal

multiplication more strikingly home to us, when we observe the fact that

this single Hebridean Island added to its population, during about 80 years

a greater number of souls than were added to the population of the Cathedral

City of Glasgow during all the generations which elapsed between the War of

Independence and the Reformation.' It did this under the stimulus of a

manufacture which rested wholly on Protective Duties injurious to the rest

of the community—under the influence of a mindless contentment with a very

low diet—and of an indulgence, not less mindless, in instincts which are

natural in themselves, but which, like all other natural instincts, require

the control of an enlightened Will. The love of offspring is a natural

instinct which we share with all creatures. But educated men do not anywhere

encourage their children to build hovels round their home, without reference

to adequate means of maintaining a civilised existence. Even among the Birds

of the Air, and the creatures of the Field, there is a wonderful, and even a

mysterious law by which a wholesome dispersion is secured, and limited areas

of subsistence are kept from being overstocked. It is a curious fact, quite

common in the Highlands, that small areas of arable land which can never be

enlarged from the nature of the country, are frequented by a single pair of

Partridges, producing a single covey every year, which, even when never

shot, never remain to multiply. It is true that Man has powers and resources

which the lower animals have not. It is true that with every new mouth that

is born, two new hands are born to feed it. But it is not true that the two

hands have power in all circumstances to earn new subsistence. Sustenance

cannot be sensibly increased upon St. Kilda. Nature intervenes and kills off

the children by a horrible and mysterious disease. Even those that remain

live largely upon charity; and are now said to exhibit the moral

deterioration which such dependence always causes, when it becomes habitual.

This is an extreme case. But it is very little more extreme than the case of

other Hebridean Islands. The love of Race is another natural instinct. But

educated men do not cling to spots of birth when wider regions invite to

wider duties, and to more fruitful works.

Sooner or later Nature finds out the sins and

blindnesses of all her children. We know what were the results of the Potato

famine in Ireland, where it fell on a population which had never been

redeemed from a terrible continuity of Celtic usages, and had never enjoyed

the opportunities afforded to the people of Tyree, by the abolition of

Middlemen, by the formation of separate holdings, and by rents kept down to

a low rate on purpose to let them live with exceptional ease. The same

effects resulted where all these opportunities had been afforded, but where

they had not been put to the right use by minds adequately prepared. There

was imminent danger of starvation. It was prevented by charity—the charity

of Proprietors generously aided by the charity of the Public. This charity

was rendered effective in the Hebrides by the comparatively limited area of

distress. The rest of Scotland suffered great losses in one article of

produce and of sale. But no part of Scotland suffered any danger of famine,

except those parts of it where the old mediaeval ignorances had been

suffered to survive. There never was so clear a lesson. Conviction was

forced on the poor people of the island of Tyree, and they addressed to Sir

John M'Neill, who was then at the head of the Board of Supervision for the

Poor, an earnest and even a passionate petition asking for assistance to

emigrate to Canada. I have nowhere seen a more forcible and more conclusive

plea set forth in favour of this remedy.' It fell to the lot of my Father

and myself to respond to it. At great cost we enabled upwards of a thousand

people to go where they could put to use the admirable elements of character

which never fail to be exhibited by Highlanders when they move out into the

stream of the world's progress. When I visited Canada and the United States

in 1879, I had the warmest invitations from Highlanders who had emigrated;

and the accounts of success were universal,

I take but little merit to myself, that in the face of

proofs so ample, and of results so terrible, I determined—with due regard to

local circumstances, and to a past which could not be too suddenly reversed

without hardship—to return to the principles which—starting everywhere from

the same conditions—had secured the wealth, the comfort, and the

civilisation of the rest of Scotland. Subdivision was stopped. Existing

subdivisions, when vacant from death, insolvency, or migrations, were never

put up to competition, as they would have been under Middlemen. They were

invariably added to the holding of the nearest neighbours who could take

them. Some new Tenants from the Low Country were brought in, who could show

new methods, and introduce some circulation of ideas into a stagnant air.

By, the steady prosecution of this process during forty years, some approach

has been gradually made to the condition of things which was aimed at by the

old Field-Marshal. With the increasing size of holdings, comfort and

prosperity have steadily advanced. But the tendency to revert to ancient

habits reappears from time to time; and the encouragements of a very

ignorant sentiment " out of doors" has lately led to an attempt to go back

through the paths of violence to the ruinous practices of the past, in spite

of all reason, and in spite of a long and a terrible experience.

I have spoken of the wonder that must often strike us

when we look back on the slowness of Mankind in opening their eyes to the

most obvious facts of nature, and to conclusions of the reason which now

appear to us quite as obvious as the facts. There is one signal example of

this connected with the history of a large part of Scotland, which applies

not to the poorer, but to the more educated classes, and especially to the

Landowners. An immense area of the Western and Northern Highlands is

occupied by high and very steep mountains. We have seen that only little

bits of them were ever put to any use at all under the old system, and even

those bits were used for only about six weeks in the year. For several

generations it had been known in the Border Highlands that such mountains

were most valuable grazings for sheep, which could be fed in thousands upon

their steepest surfaces, and could remain on them all the year round. Yet it

was only very slowly and very late that it dawned upon Farmers, or upon

Landowners, that the Highland mountains could be put to the same use, and

could be thus redeemed from all but absolute waste. The enormous addition

made by this discovery to the natural produce of the country, is very apt to

be forgotten now, because of the great ignorance prevalent on the extent of

area which was thus, for the first time, made contributory to the comforts

and sustenance of mankind. On my own estate there is one Mountain which,

with its spurs and peaks and shoulders, occupies more than 20,000 acres. Of

this great area only about 500 acres are arable, and many of these have been

reclaimed and enclosed at great cost, within the last fifty years. Of the

rest, probably not more than 1000 acres would be available for Cattle. All

the remainder, at least 18,500 acres, are very steep, and many of them

either actually, or almost, precipitous. No other animal except Sheep could,

or ever did, consume the grasses which clothe these surfaces more or less

abundantly. Yet they can and do feed some 8700 Sheep, without inter fering

with the comparatively few Cattle which were ever reared in the olden time.

If, now, we look at an Orographical Map of the Highlands, we shall find that

this case is the typical case of the Western Highlands and of the Northern

Highlands, embracing the larger half of the Counties of Inverness, Ross, and

Sutherland. Sir John Sinclair calculated that before the introduction of

sheep-farming, the whole produce exported from all the Highlands did not

exceed £300,000 worth of very lean and poor Cattle. Tinder Cheviot Sheep he

shows that the same area would produce at least twice the value of mutton,

or £600,000, besides all the Wool, equal to a further sum of £900,000. This

Wool, again, when manufactured, would represent a value of at least

£3,600,000 of Woollens. The total difference therefore between the produce

of the Country, under the new system as compared with the old, was as the

difference between £600,000, and £4,200,000—this difference being all added

to the comfort and resources of Mankind.

It does seem almost incredible that Highland

Landowners and Tenants should have been so slow to find out an application

and a use for the Moors and Mountains they occupied or possessed, a use

which in reality constituted as much the addition of a new country as the

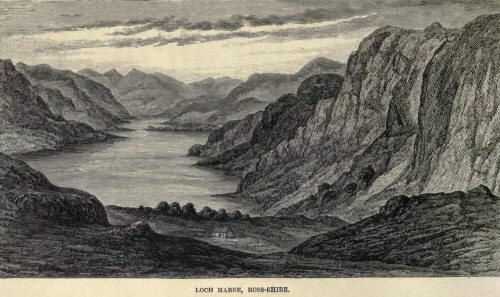

recovery of the Bedford Level from the Sea. The Mountains round Moffat in

Dumfriesshire are hardly less steep or less high than the Mountains round

Loch Maree in Ross-shire, or round Loch Laxford in Sutherland. The Highland

Mountains had even an advantage over the Border Mountains, that they were

nearer to the Gulf Stream, and snow lay less long upon them. Yet the

stupidities of Custom and Tradition were so difficult of removal that

Sheep-farming spread as slowly as the Potato, or the manufacture of Kelp. No

doubt the new Sheep-farming involved some local displacement of population,

because Sheep could not be supported without access to low ground, which was

sometimes occupied by "Clachans," liable to periodical distress and famine.

But this displacement of population was far less than that which had been

involved all over the Low Country by the abandonment of Runrig, and in the

Border Counties by the Sheep-farming which had superseded the Moss-troopers.

Neither again did it involve necessarily in all cases very large farms. The

Highland Counties have at this moment a much greater variety of holdings in

respect to size, than the most thriving Lowland Counties. Neither again did

it involve any general substitution of Lowland farmers for Highlanders. Some

of the earliest sheep-farmers were Highlanders who had acquired capital by

industry. Others were Lowlanders who brought knowledge of management, and

imparted it, to the immense advantage of the country. It remains therefore a

wonderful example of the slow progress of new ideas that the Highland

Proprietors adopted Sheep-farming on the hills so slowly and so late as they

actually did. Although it began as soon as 1768, it was not universally

applied to the wasted areas till as late as 1823.

But there is another phenomenon, even more wonderful,

which is equally common—and that is, the coming back of old blindnesses—the

revival of old errors—and even the passionate return to practices which

Nature has condemned. Yet this phenomenon has its analogue in the material

world as well as in the World of Mind. It is now universally admitted that

Development, or Evolution, does not always work in one direction. It works

downwards as well as upwards. As Tennyson expresses it—"Thronèd races may

degrade."' There is even reason to believe in a constant force tending to

revert to earlier and ruder stages of existence. Whether this be so or not,

the fact is certain that there are many creatures that fall from a

comparatively high, to a comparatively low, organisation. The freedom—nay

the very organs—of locomotion are abandoned and cast away. Even the noble

faculty of vision is lost. The creature becomes fixed to a bit of rock, or

to the shells and exuvie of dead things. So it is with Man. At the beginning

of this Work I have referred to the influence exerted over our longings and

desires by the pressure of modern life—the "fuinum strepitumque Rom"—the

strain of Work in the pursuit of Wealth—or the not less trying strain of

Mind in a speculative age in the quest of satisfying Truth. All this tends

to throw a most false glamour on the ages which have passed. The old tastes

for a Wild Life return upon us, in- herited through many generations.

Most of us know the feeling. It is pleasant to return

to childhood, and the pleasures of imagination. I never read any detailed

account of so-called "primitive" life in any of the happier climates of the

world, without at least some passing feelings of desire to join in its

freedom and pursuits—to live in Pile Dwellings on the lagoons of a Coral

Sea, or in huts on the tops of trees—to watch the Birds of Paradise in the

Forests of New Guinea—to shoot reedy arrows at the great Ground Pigeon—or to

hunt for the wondrous hatching-mounds of the Brush Turkey. Not less

attractive to other tastes would it be to go back to the Epoch of the

Clans,— to sail, and to fight, and to spoil in beautiful Galleys, with all

their bravery of war. It is perhaps less easy for civilised men to think

with any envy of the old Celtic habits—of the wattled huts, jointly

inhabited with the cows and calves—of the perpetual atmosphere of

Peat-reek—of all the hardest labour left to women, and of seeing them yoked

to Harrows as described by Mr. Macgregor, writing as late as 1838. But

imagination has a wonderful power of winnowing out all facts that are

disagreeable, and of resting only on those which have a flavour of the

picturesque. We have seen that not only the charm and glamour of these old

habits, but the actual delight of exercising the powers of" Chiefery" with

which they were inseparably connected, had been strong enough to corrupt the

noble chivalry of Norman Barons, so that even a man near in blood to Robert

the Bruce had descended to the level of a mere "Wolf of Badenoch." We have

seen how, in a much later day, another conspicuous example of the same

influence had been displayed by Sir James Macdonald, who was known in the

Palaces of the Kingdom as a most polished and accomplished Knight—but who,

when he returned to Islay or Kintyre, became the bloody and the fierce

1iIacsorlie. In our own time it has too often an influence not indeed so

formidable in action, but hardly less corrupting in opinion. Harmless in the

form of mere sentiment and poetry, it ceases to be harmless when it perverts

History and loosens the hold of Mind over the rights and obligations upon

which every Society must be built.

In this form it acts as a solvent upon Opinion which

is the root of Law. It subordinates the Reason to Fancy—it elevates the

ignorant Declamation of the Platform over the responsible decisions of the

Bench. This is a return to the power of "Chiefery" not in its ancient and

nobler form but in a new and debased embodiment. It is a reversion, as

Darwin expresses it, in Biology, to an old and ruder type. It is however

worse than this. It is a mere travesty and corruption of that violence

against which the Monarchy and the civilisation of Scotland had to wage for

centuries one long continuous war. It is the true modern analogue of the

worst Anarchy of the Clans.

It is curious to observe the different direction which

this kind of sentiment has taken in regard to the country formerly inhabited

by the Border Clans. That country has been infinitely more changed and more

depopulated than the Celtic Highlands. The vast stretches of moorland, and

the long vista of vacant Glens which strike the eye on the borders of

Dumfriesshire and the Upper Wards of Lanarkshire, are far more desolate of

human habitation than any similar areas in the Highlands possessing equal

possibilities of reclamation. But more than this: the greener and lower

Valleys which are so beautiful in Selkirk and Roxburgh, are almost entirely

destitute of the smaller Holdings which are abundant and successful all over

the Counties of Argyll and Inverness. How does true Poetic Sentiment deal

with the memory of the days when these Valleys were full of a military

population—when a few powerful Chiefs could summon at the shortest notice

armies of 10,000 men? It sings of those days indeed. But the Singer does not

pretend to wish that they should return. Let us listen for a moment to the

melodious words in which the great Minstrel of the Borders recalled the

Military Ages of that pas-

toral land in which, when a child, he lifted

his little hands to the lightning in a raging Thunderstorm,' and shouted

with excitement "Bonny, bonny!":-

"Sweet Teviot! On thy silver tide

The glaring

bale-fires blaze no more:

No longer steel-clad warriors ride

Along

thy wild and willowed shore;

Where'er thou wind'st, by dale or hill,

All, all is peaceful, all is still,

As if thy waves, since Time was born,

Since first they rolled upon the Tweed,

Had only heard the

shepherd's reed,

Nor started at the bugle-horn."

This is delightful and legitimate. But more than this

would be childish. Scott himself became a Landowner in that very country—and

latterly he possessed no inconsiderable Estate. He built a Baronial Hall.

But he did not restore a Cottier Tenantry. He enclosed and planted. But he

planted Larches. He did not invite the Workmen making high wages in Hawick

or Galashiels to come back to starve on patches of corn and of potatoes

along the once populous "Haughs" of Tweed. The unreality on which much of

this kind of sentiment is founded was never more curiously illustrated than

when the Government chose as the Head of a Commission appointed to inquire

into the Small Tenants of the North and West, a Scotch Peer' whose own

Estate is situated among the long "cleared" sheep pastures of the Southern

Highlands, and in a locality which is specially described by Sir Walter

Scott in Marinion as a perfect picture of solitude and depopulation.' This

distinguished Scotchman has given elaborate advice to Highland Proprietors

for the extension—not merely of small Holdings —but of the special form of

these which is least advantageous—that of Joint or- Township Farms. There is

nevertheless not the slightest reason to believe that he himself or any of

his brethren, would consent to cut up any portion of their great sheep

grazings, or of their comfortable and single arable Farms, for the purpose

of restoring the population of the Military Ages. Many Owners in the Lowland

Counties now wish that they had, as the Highland Counties have, more small

Farms, and fewer of the largest class. But no man who knows anything of

Agriculture, or of the influences which promote its progress, would ever

recommend the revival of the old Township System. In my own experience I

have always found that the moment any "Crofter" becomes exceptionally

industrious and exceptionally prosperous, he earnestly desires, above all

things, that his grazings as well as his arable land, should be fenced off

from those of his neighbours, so that he may have the exclusive use of his

own faculties in the better tillage of his ]and and in the better breeding

of his stock. The multiplication of small Farms, indeed, such as will

profitably employ the whole industry and capital of individual men, is an

object most desirable. But the conditions of success vary with every

locality, and can only be determined by local knowledge. It cannot be

settled by a vague desire to revive the usages of a time which has passed

away for ever.

Sentiment, however, must never be surrendered to those

who have little knowledge and no balance. Such are the men who are very apt

to claim it as their own, whilst instructed men are too apt to leave it in

their hands. Sentiment can be strong as well as weak—healthy as well as

sickly, manly as well as mawkish. It can fix its enthusiasms on what is

really good, as it too often does on what is only picturesquely bad. The

cruelties, treacheries, disloyalties, and brutalities of the Clans were mere

developments of corruption, due to the divorce between them and all settled

Government and Law. They represented nothing but anarchy in their relations

with the Nation and the Kingdom, and nothing better in their relations with

each other. But the root and the principle of their organisation was that of

a Military Tribe, recruiting from all directions,—practising obedience,—

acknowledging authority,—and loving its hereditary transmission from those

who had first afforded guidance, conduct, and protection. This is a

constructive, and not a destructive or anarchic principle. It needed only,

to be turned in a right direction to become one of the steadiest of all

foundation-stones for the building up of a great structure in the light and

air of a higher civilisation. It was thus that in the transition between the

two Ages, the broken fragments of a hundred Septs enlisted under the Banner

of the Black Watch, and began the immortal services of the Highland

Regiments. Yet this is only a late and picturesque incident in a long series

of events. Nothing is more striking or more poetic in the history of

Scotland than the slow and arduous processes by which the rough energy of

the Military Ages was transformed under the ages of industry and of peace.

Malcolm Canmore had begun the transformation by his own Union with the

Daughter of another blood. Robert the Bruce continued it by the welding of

broken Races in the heat and fire of Battle. Between the War of Independence

and the Union of the Crowns it was one long, continuous, constant, struggle.

But by slow and steady steps the work was done, and Scotland became a Nation

with a noble and a settled Jurisprudence. Our Kings became our only Chiefs:

our Country became our only Clan. Her Law, the best symbol of her History,

and the best expression of her Mind, became the only authority to which we

bowed, and the only protection to which we trusted. Under its shelter man

could have confidence in man, because there was no fear of that which even

the old Celts ranked with Pestilence and Famine—the breaking of the Bonds of

Covenant. In this high field of Human Energy,—the establishment of that

confidence in Law which is the nearest approach we can ever make to the

methods of the Divine Government,—Scotland may well be proud of the old

beginnings, and of the steady growth, of all her National Institutions.

Among these Institutions there is one of purely native

origin which, perhaps, as much as any other, is a striking embodiment of

this principle, and a splendid illustration of its effects. I refer to her

Banking system. Barter, as we all know, is the earliest form of Exchange,

and under that system if the Seller can bring his produce to a market, and

the Buyer can carry it away in safety, no higher kind of security is

required.. Then comes Money as an abstract representative of Value,

immensely facilitating Exchange, by providing an article with which, and for

which, everything can be got from somebody. Lastly comes Credit, the highest

and the most powerful of all agencies for promoting the intercourse of men.

It is the highest because it is most purely the work of Mind—the most

absolute expression of confidence in the universal authority of Law. In

other countries the intervention of the State has been required to establish

Banks, and the work assigned to them has been lauded as among the highest

efforts of Statesmanship. In Scotland an immense network of Institutions for

the universal diffusion and organisation of Credit, has been spread, as it

were, by a natural growth indigenous to the soil. In Scotland there is a

Bank for about every 4000 souls of the total population. Ten of them

represent a paid-up capital of above Nine Millions sterling, and Deposits to

the amount of more than Eighty Millions; their Branches are all over the

country. Thus everywhere men are able to take advantage, not only of their

savings, but of the credit in which they stand for their character in

business—that is for their honesty, their industry, and for all the mental

aptitudes which give promise of success. The whole of this vast system of

Credit is founded upon confidence in the Law—constituting a Wages Fund

co-extensive with the possibilities of Industry and of Knowledge. It would

all crumble at the touch of Anarchy. Under the confidence which this Reign

of Law ensures, Mind in all its forms, whether of enterprise, or of

invention, or of organisation, or only of patient perseverance, has made an

entirely new world of Scotland. It has reclaimed her soil, it has deepened

her rivers, it has built her. commercial navies, it has brought into her

harbours the products of the most distant regions, and it has redeemed her

own people, immensely multiplied, from chronic poverty and frequent famines.

There must be something wrong with ourselves, and not

with the Order of Nature, or with the Designs of Providence, if we can find

none of the pleasures of the Imagination, and none of the gratifications of

Sentiment, in changes such as these. Nothing can be more certain than that

we are but accomplishing part at least, and an essential part, of our

mission in the world when we turn the desert into the fruitful field.

Nothing can be more certain than that it is our duty to put our Talents out

to Use, and not to hide them in a napkin. Most of these Talents have their

poetic side. Slothfulness is not one of the Christian virtues, even when it

is passed amidst picturesque surroundings. The Hebrew People were not devoid

of Poetry or of Sentiment, and yet their Songs and their Prophecies are full

of the imagery derived from the improvement of the soil, as well as of the

precious and beautiful things which were brought in Commerce by the ships of

Tarshish. With them the Olive, and especially the Vine, were the symbols of

cultivated fertility; and in connection with the Vineyard, in particular, we

have the most touching and passionate allusions to all the care and labour

bestowed upon Enclosures as the best type and symbol of the work needed in

the higher cultivation of the soul. The "fencing" of land, and the

"gathering out the stones thereof," and the "planting" of it, and the

building "in the midst of it," are as apposite a description of the work of

Reclamation in Scotland as it was of the same work in Palestine. The taking

away the "Hedge thereof," and the "breaking down the wall thereof" are used

as the best Images of utter Desolation,' whilst the ravages of the wild

creatures which fences are intended to exclude are similarly used to typify

the invasions of the sacred fields by the arms of Heathendom.' There is too,

in the Book of Proverbs, a striking description of the ignorant and lazy

habits which had afflicted Scotland: "I went by the field of the slothful,

and by the vineyard of the man void of understanding; and, lo, it was all

grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered the face thereof, and the

stone wall thereof had been broken down. Then I saw, and considered it well:

I looked upon it, and received instruction. Yet a little sleep, a little

slumber, a little folding of the hands to sleep : so shall thy poverty come

as one that travelleth; and thy want as an armed man."' Yet, beyond all

question, the "pruned vine" is a much less picturesque object than the

Briers and the Thorns which ignorance or violence may allow to choke it. On

the other hand, the clustered grapes,—and the winds passing over fields of

corn,—and the flocks browsing in perspective upon great plains,—and the

sheep herded on the mountains—are all pictures full of poetry—far higher

than that which circles round the deeds and the pursuits of half-barbarian

Man.

We cannot go back to the Primitive Ages, whatever else

we do. We must live in our own time, and we must put to culture and to use,

such talents as come to us from the inheritance of the Past, and from the

opportunities of the Present. It is a delusion to suppose that the sin of

covetousness belongs specially to the later ages of the world. The naked

Savage covets more of his beads, or of his bits of iron, as much as the

civilised Man covets some new indulgence. Modern Industry has its own

dangers, and its own evils, but the truth is that the pursuit of Wealth

under the conditions of civilisation, having in it more of Mind than the

same pursuit under conditions of Barbarism, tends to be better and higher in

its moral character. There is less in the mere getting, and more in the

intellectual interest belonging to the processes through which the getting

comes. The Machine Maker thinks as much of the perfection and accuracy of

his work, as of the price he gets for it. The Shipbuilder thinks most of the

fine "lines"—of the speed, and capacity, and strength of his ships. The

Skilled Workman rejoices in his manual dexterity, and takes a pleasure,

purely intellectual, in the triumph of his hands—in the straightness of his