|

EARLY COUNTRY COURTSHIP—THE COUNTRY WEDDING

EVER since Adam fell a prey to the charms

of Eve man has always sought for woman's

favor. In the salon of the courtier and the

cabin of the backwoods settler Cupid's fatal

shafts have fallen alike. The more primitive the

life, the more unaffected the courtship. In the

early days of the country many opportunities were

afforded the young people for becoming better acquainted the

frequent visits, especially in the winter time,

the dances and the various bees in which they took

part, threw the young people into each other's company

and with the usual effect in such cases. When John

became enamored of Mary he made frequent visits to

her father's house and could be seen sitting with the

family around the old fireplace, where, if his suit was

favored by the parents, he was always a welcome guest.

The folks being kept busy during the week, Sunday was

the great day for courting, or "sparking," as it was

commonly called. On pleasant Sunday afternoons

rustic couples might frequently be seen walking arm-in-arm along the

country roads, the young man, perhaps, carrying his sweetheart's parasol.

The country church was a common place of meeting. Many of the young men

were attracted thither on this account, if from no higher religious

motive, and each would wait patiently at the church door until his special

enamorata appeared, when he would quietly walk up beside her and ask for

the privilege of "seeing her home." Sometimes a coquettish girl would have

several strings to her bow. This not only set the people to wondering

which young man would come out first choice, but often resulted in a

quarrel, and sometimes, perhaps, a fistic encounter between the aspirants

for the young lady's favor. Alter a reasonable period of courtship, during

which the girl's mother had helped her prepare a stock of clothing (the

trousseau is the more fashionable word), etc., the couple would be, of

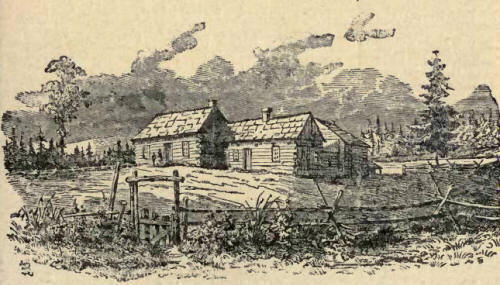

course, happily married and would take up their residence in a home of

their own, which, if the young man's relatives were well-to-do, was

frequently the "back place," a farm of fifty or one hundred acres on the

concession at the rear of the old homestead or close by, where the young

man had likely previously erected a log house and made a small clearing.

Here, with a table, a bedstead, several chairs and the young woman's

outfit of bedclothing, dishes, etc., provided for her for housekeeping,

they would commence their married life. Such was about the usual course of

events. Country courtship was not without its difficulties. Sometimes the

neighborhood was startled by the announcement of a runaway marriage, the

daughter of some well-to-do farmer eloping, perhaps, with her father's

hired man, or with some other objectionable person of whom her parents

disapproved. The old adage that "the course of true love never runs

smooth," and that "love laughs at locksmiths," etc., was then as true in

humble life in the bush as it has ever been in higher circles. Where

suspicions were entertained of the young lady being likely to make an

undesirable choice, a strict watch upon her movements was likely to

result. But woman's wiles and cunning would conquer in the end. Where

there was the will a way was found, even to the stealing out by the window

and descending by a ladder or ropes, or by more primitive means, to meet

her lover according to pre-arrangement. Forty or fifty years ago, across

the border in the rural districts of New York State, runaway marriages

were even quite fashionable. Even if the parents of the bride knew that

she was engaged, she would often, unknown to her parents and friends, run

away and get married and in that way give them a surprise. It is said that

the poorer classes in New York State would frequently pay the magistrate

for marrying them with a bushel of apples or a bag of turnips. Canadian

law was not so favorable to elopements, for the banns of marriage had to

be published beforehand, and when licenses were issued the couple had to

prove that they were of marriageable age. Yet, with all these precautions,

the law was frequently evaded.

The Country Wedding.

One of the most interesting social events of the

country neighborhood was the wedding. Among well- to-do people it was

generally made the occasion of much merry-making, all the friends and

acquaintances of the contracting parties being invited to the festivity.

Old and young mingled together and greeted one another with smiling faces

and pleasant how-d'ye-does. In the early days the young couple,

accompanied by several of their friends, drove off in a wagon or sleigh to

some magistrate's or clergyman's house to have the nuptial knot tied; at

other times the minister would come to the house of the bride's parents to

perform the ceremony, or possibly the couple went to the church, if it

happened to be convenient, to have the ceremony performed. In some

localities, when buggies became common, this proceeding was followed by an

afternoon's drive around the country. A long line of buggies could be seen

on the country road, the procession being led by the bridal couple (the

bride being distinguished by the long white bridal veil which she wore),

followed by the bridesmaid and groomsman, and after that by the younger

members of the wedding party, all coupled off. The groom generally tried

to have the fastest horse in the party, for if he did not others would get

ahead of him and secure the prize which was offered to the one who got

back to the house first. On such occasions the mischief-loving boy put in

his work, and it was by no means a strange thing to have the wedding party

brought to a halt by a rope stretched across the road until a donation was

made to the roysterers. This buggy jaunt was the forerunner of the wedding

trip or tour of the present day. When leaving home the pair were generally

followed by a fusillade of old boots: this was supposed to insure them

good luck on journey through life. Nowadays the Oriental custth of

throwing rice has been added, and at one wedding known to the writer the

event was announced by the bride's father firing off a gun three times. In

the summer time, if there was not room enough in the house for the guests,

the wedding dinner was partaken of outside; long tables being set out in

the orchard or lawn, or on the threshing floor of the barn, loaded down

with the delicacies of the season, the tables being ornamented with

bouquets of flowers, and with a three or four storied frosted wedding cake

in the centre, a piece of which the young ladies always carried home with

them for placing under their pillows at night, in order that they might

get a vision of their future husbands. These weddings were not without

their funny incidents, and occasionally the guests were placed in an

embarrassing position by the lateness or non-appearance of the groom or,

may be, the unwillingness of the bride at the last moment to consent to

the ceremony, the confession being finally obtained from her that she had

been married clandestinely to some secret lover. Sometimes the bashful

country swain, in his awkwardness, would find, when asked for the ring,

that he had mislaid it, in which event the clergyman has been known to

marry the couple with the key of the door, the ring being found afterwards

in the lining of the young man's coat. After the ceremony was over it was

the custom for all the ladies in turn to kiss the bride, and sometimes the

young men would try to secure the first kiss, the groomsman oftentimes

managing to do this before the groom. It is told of one minister that he

always made a practice of kissing the bride; the only time he was ever

known to object was when the couple were colored. In the evening, after

the wedding, the guests would assemble in loads for the all-night dance, a

favorite trick of the driver of the sleigh in the winter time being to

upset the young folks into a snow-bank. There would be considerable

rivalry among the young men to get the second dance with the bride, the

husband always being allowed the privilege of the first. One of the last

things on the programme was the charivari, which the young men in the

neighborhood who had not been invited to the wedding got up for the

entertainment of the guests, the discordant notes got by hammering on the

mould-board of a plough, or from some equally crude musical instrument,

disturbing the tranquillity of the midnight air. As a rule the charivari

was gotten up to celebrate the wedding of an old bachelor or a widower, or

some objectionable person that the boys thought would give them a good

time or a five dollar note to spend at the country tavern.

|