|

CIDER AND CIDER MILLS-MAKING APPLE BITTER-HONEY

GATHERING, STRAW HIVES AND SUPERSTITIONS ABOUT BEES-SHINGLE MAKING-FLAX

CULTURE-TANNING LEATHER.

AFTER the orchards which

the first settlers planted out had matured

(which for apples generally took about

twenty-five years), they had fruit in abundance.

Large quantities of apples were shipped away to the

new settlements, where the settlers had none. The

balance was either packed away for winter use, or made

into cider and apple-sauce, or apple-butter, as some still

call it. We cannot say just where the custom of making

apple-sauce originated, but apparently our forefathers

brought the custom with them from their former homes

in the States. It is probable that it was introduced by

their ancestors when they came from Europe, where the

custom also prevailed. The windfalls, i.e., apples which

had been blown down by the wind, along with apples

of a poorer grade were heaped up in a waggon-box and

taken to a cider mill, which some person in the neighborhood was

sure to possess, one mill sufficing for a number of

families, although cider-making was a business of itself, and was a source

of profit to any one owning a mill.

Cider was generally made out of

the sour apples, the sweet apples being kept for thickening the cider

after it had been boiled into syrup. In the early days the apples were not

wormy, and, therefore, did not require any more attention than a slight

washing, and sometimes not even that, before being sent to the mill. The

cider mill and press were usually kept in an outhouse erected for the

purpose. The apples were first ground up in the mill. The cider mill

consisted of two solid wooden cylinders, from two and a half to three feet

in length, and one and a half feet in diameter, placed close together,

horizontally, in a framework of wood. The surface of the cylinders was

ribbed or fluted, so that the flutings of the one cylinder fitted in

exactly between the flutings of the other, like the cogs of two wheels.

The apples being poured into a hopper were drawn in between these wooden

wheels, which crushed them into a pulp. One of the cylinders was longer

and reached above the other. To the top of this long cylinder was fastened

a pole; a horse was hitched to this pole and driven around the mill,

causing the cylinder to revolve. After the apples had been put through the

cider mill, the pulp thus formed was placed in the press and the juice

squeezed out. The first press was a clumsy affair, the hand or screw press

coming later on. A square box arrangement, made of hardwood slats, was

placed on a heavy beam; this beam had an upright piece of timber fastened

to the end of it; another beam, say about thirty feet long, with one end

mortised in this upright piece, extended over the box and had another box

weighted with stones attached to the end, so arranged that by turning a

wooden screw that fastened into the beam the box and beam could be raised

or lowered so as to bring the weight of both down on the apple pulp which

had been placed in the first box. In the bottom of the slat box was placed

a layer of straw. The ground up apples were put into a cloth and placed on

top of this, and on the top of the whole was placed a number of wooden

blocks, which extended above the top of the box for the beam to rest upon,

and so squeeze out the juice. Cider was mostly used for making

apple-sauce, but a few barrels, called by some rack cider, were kept for

drinking purposes, for the different bees, and harvest time, and social

gatherings. After temperance sentiments gained ascendancy the custom was

abolished, for, after the cider had been kept a while, it became "hard."

Hard cider, because it contained a percentage of aIcohol, was very

intoxicating. It was sometimes called "Apple Jack." Cider was also made

into vinegar, and of the best quality; by being left exposed to the air,

i.e., not corked up, it became vinegar in a few months' time.

Among people who had no orchards it was customary to

make pumpkin sauce. In appearance it was much like apple-sauce, but had,

of course, a different flavor. Some of the pumpkins were boiled, and the

juice squeezed out. The juice obtained was put into a kettle over the

fire, sliced pumpkins and sometimes sliced apples being added, and the

whole then made into a sauce.

Making Apple Butter.

The boiling down of the cider into sauce or apple

butter, as it was called bybome, was ajob which required a good deal of

time and labor. On the morning of the day set for the work, the big

copper, or brass kettle kept for the purpose, and very often holding a

barrel of eider, was brought out, scoured, and after being hung on a pole

placed over crotched sticks fixed in the ground a few feet apart, it was

filled with cider and a brisk fire built underneath. The boiling down of

the cider to a syrupy consistence was commenced early in the morning;

about three or four o'clock in the afternoon the apples (preferably

sweet), which had been previously pared, cored and sliced, were added.

After three or four more hours' boiling over a slow fire, so that the same

would not burn, and constant stirring with a short board or paddle full of

holes fastened to the end of a long pole, or an appliance fitted with

paddles and placed in the kettle to prevent the apples from settling to

the bottom and burning, the sauce was finished. It was

then flavored to suit the taste, with either cinnamon, allspice, nutmegs,

sassafras or other spices, put in crocks and stored away for future use.

The keeping qualities of the sauce depended largely on the amount of

boiling given it. Why it was called "apple butter" we do not know. It may

have been because it was so often spread on the bread like butter, or it

may have been because when kept very long it would sometimes get solid and

could be cut with a knife like butter. The name was not inappropriate.

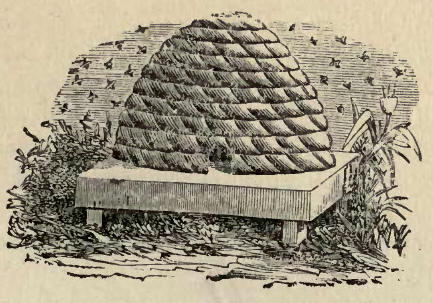

Honey Gathering, Straw Hives, and

Superstitions about Bees.

Sitting around the garden walks

were to be seen the conical-shaped straw hives. When the season for honey

gathering was over, the bees were suffocated with smoke, or by the fumes

of burning brimstone, and the honey taken from the hive, a few hives being

reserved for breeding purposes the following year. Some peculiar

superstitions, too, prevailed regarding bees. If there happened to be a

death in the family, the duty devolved on some one of tapping on the hive

and notifying the bees, else it was believed the bees would die also.

When the bees swarmed and were

taking their flight all hands would get out and hammer on tin basins and

pails, and it was the custom to flood sunlight into their midst by the use

of a mirror. The noisy sound made was supposed to represent thunder and

the flash of light lightning, so as to give the bees the impression that a

thunder storm was coming up and so cause them to alight near home. This

practice can not exactly be called a superstition, and whether or not it

was of any value in preventing the bees from getting away out of reach is

doubtful. It was considered unlucky to sell a hive of bees. If it were

known that a man had more hives or ' skips" of bees than he wanted, any

person wishing to get a hive would simply go to this man's place and carry

away one of his hives. He would not pay for it in person, but would leave

an equivalent in money lying around where it could easily be seen.

A fermented liquor called "methigelum"

was made by some of the people from honey. After most of the honey had

been drained from the comb, the residue, partly honey and partly wax, was

put into a vessel and covered with water; after a few days it fermented

and became quite intoxicating. It was an imitation of the ancient "mead."

Shingle Making.

When the first houses were built

in the backwoods, the settlers could not afford the time to make shingles.

The practice was to cover the roofs of their houses with bark or hollowed

basswood logs, fitted one over the other in tile fashion. The first

shingles used were very long (three feet) and very heavy, being split out

of cedar, pine, ash, or oak blocks by the frow (sometimes the axe), but

were not shaved. They served the double purpose of shingles and sheeting.

There being but few and far between sawmills, lumber was not to be easily

had for placing on the pole rafters. Long pieces of split cedar, three or

four inches wide, placed a foot or two apart, were put up lengthwise with

the house across the rafters. The shingles were fastened on these by

wooden pins, each row being lapped over the one preceding it. It is true,

also, that even after the people commenced to use the short (eighteen-inch

and less) shingles they did not always use sheeting. Strips of lath, three

or four inches apart, were laid across the rafters, to which the shingles

were nailed. This was thought to preserve the shingles, as it allowed the

air to circulate underneath the roof and kept the shingles dry. The

shingles in use now, when they first came out were not sawn, but were

rived out of blocks of cedar or pine. The instrument used was the frow.

The blocks cut the required length were split by the frow into thin pieces

of board which were afterwards shaved smooth and thin and shaped by the

drawing knife.

Flax Culture.

One hundred years ago the cotton

industry in the Southern States was only in its infancy, the introduction

of the spinning jenny and of machinery for cleaning the cotton wool and

for weaving it into cloth having since caused it to grow to enormous

proportions, and has resulted in the reduction of the price of cotton

cloth to a very low price, within the reach of the poorest. The cost of

linen goods in the early days was beyond the ability of the people of

small means to purchase, so they were compelled to raise flax and make

their own linen cloth. The making of the flax into linen cloth was quite

an interesting and intricate process. To get the flax ready for the weaver

required a good deal of preparation. When the plant had reached its growth

it had to be carefully pulled by hand and tied into small sheaves. These

were set up to dry and for the seeds to fully ripen and harden. Then one

of the sheaves would be held in the left hand and with a heavy stick the

seed balls would be beaten till all the seeds would drop. Perhaps about

the last of September the flax would be spread in thin layers on sod or

wheat fields. The object of this was to cure the flax, 'i.e., to partially

rot the pith, after which the fibre would readily come off. As soon as the

flax was cured, on some fine day when it was quite dry, it would be taken

and put away for winter. The next step was to use what was called a "breake."

This consisted of two sets of long wooden knives, probably four or five

feet long. These knives were fastened into wooden blocks and the lower set

set upon legs. The upper set of knives was placed upon the lower set, each

knife fitting in between two of the knives of its companion. The two were

carefully hinged together by a wooden pin at the back. There was also a

wooden rod on the top of the upper set about as long as the knives. This

preparation was for the "breaking" of the flax. The operator would take a

bunch of the flax in his left hand, lift the upper part of the breake with

his right hand and bring it down with a good deal of force on the bunch

which he held in his left hand. It required some minutes of pounding to

break up the pith inside the fibre of the flax, and it was none of the

easiest kind of work. Often it was done out of doors and a large fire

would be kept up near the large bundles of flax. The next step in the

process of preparation was the *single board. The swingle board was about

four feet long, placed upright and nailed at the bottom to a heavy wooden

block. The top was in the shape of a hand with the index finger extended

and the others closed. The top end was sharpened. Upon this sharpened end

a bunch of the broken flax was placed and held by the left hand, and with

the right hand the operator would dress the flax with a long wooden sword

sharpened on both sides. The steady, well-directed strokes of the sword

removed the "shives" or loose pith. To do this meant work, besides being

very unhealthy on account of the dust. The last step to prepare the flax

for spinning was the drawing it through what was called a hackle or flax

comb (Ger., liechel). This consisted of a board about eight inches long by

four inches wide, full of rows of long steel spikes. Bunches of flax were

drawn through this comb, which removed all the coarse fibres; what was

left was soft and silky and was made into cloth for the finer linen goods.

The coarse fibre was called tow

and was used for various purposes. Ropes and coarse cloth for grain bags

and men's working pants were made out of it.

The linen cloth after it came from

the weaver was spread on the grass and sprinkled with water a number of

times each day for several weeks, to shrink and bleach it.

The home-made linen cloth was very

hard and stiff and after being washed, before rinsing, it was generally

folded together, placed over a block and pounded with a stick to soften up

the goods. The father and mother of the writer have occasion to remember

such work.

Tanning Leather.

The Indian mode of tanning was to

take the ashes left from the camp fire, and make a solution of them in

water. The skins were placed in this solution and left for about three

weeks, when the hair and bits of flesh adhering would readily come off,

leaving nothing but the clear skin or "raw hide," as it was called. This

was then worked with the hands or rubbed with sticks to make it soft and

pliable, when it was ready to be tanned. This was done by putting it in a

solution of hemlock or oak bark, and leaving it in this solution for about

three months until all the oil and fatty matter was exhausted. After this

it was again rubbed and worked with the hands to further soften it up.

This method of tanning is not nearly so injurious to the skin as the

modern method in which chemicals of various kinds are used.

The Indian mode of tanning was

adopted by some of the early settlers, who were compelled to do their own

tanning. They had a tanning-tub or atrough hollowed out of a log of wood

for soaking the skin in. Later on, every neighborhood had its tanner, who

did the tanning for the farmers. This kind of work, like many others, was

usually done on shares—the tanner keeping part of the hide for his work

and returning the balance to the owner.

|