|

SPINNING YARN—STRAW WORKING—MILKING TIME—PLUCKING

GEESE—SOAP MAKING—CHEESE MAKING—HOW SAUERKRAUT WAS MADE.

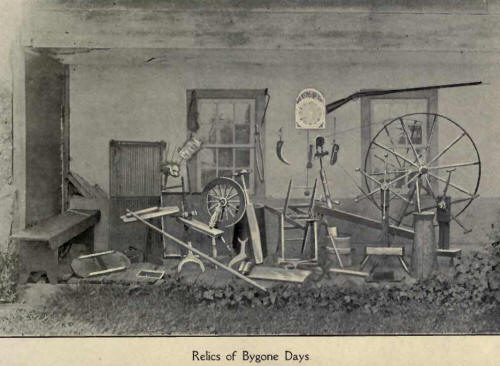

IN imagination we can see

the industrious aunt walking back and forth

beside the spinning-wheel, attaching a length

of carded wool to the spindle, then

twirling the monster wheel* and drawing the wool out

into yarn, stopping now and then to examine the thread

and singing to herself as she marches back and forth

over the floor. Day in and day out she keeps at it.

After she has a spindle full of yarn it is wound on the

reel into skeins, a peculiar clock-work contrivance

attached to the machine, making a click every time a

knot is wound on. After enough knots had been wound

on to make a skein, they were tied together and hung

up. Four skeins of fourteen knots each

was considered a good day's work. A machine

called "The Swift" was used

for unwinding the skeins when the yarn was being wound into balls.

For spinning flax a smaller wheel

was used. It was kept in motion by a treadle worked by the foot, the

operator sitting down while spinning. A bunch of flax was fastened on to

the distaff, a forked stick at the front end of the wheel. The white flax

was pulled off the distaff, attached to the spindle by the spinner, and

lengthened out into linen thread, which was tied into bundles called

"hanks."

The high wheel for spinning wool,

it appears, was used by most of the descendants of the settlers from the

United States, and was probably the kind used by the people of New

England, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The low wheel was used

mostly by the settlers from England, Ireland, Scotland and Germany.

Straw Working.

One of the many domestic

industries of the early time was the straw working. The stalks of grain

for this purpose, in order to prevent them from becoming too brittle, were

usually cut before the grain had thoroughly ripened and put away in

sheaves until wanted. Oat, wheat and rye straw (preferably rye, as it was

long and pliable) were the kinds mostly used, although the straw of the

wild rice, which grew in swales and swampy places, was considered

superior. The straw was first plaited into strands and then sewed together

into hats for both men and women, and for boys and girls. The hats were

bleached by exposure to the fumes of sulphur burnt in a covered box or

barrel. This kind of hat is still worn among the farmers. There are,

however, but comparatively few of the women nowadays who understand how to

make them, this work being generally done in hat factories. The straw

beehives were quite common fifty and sixty years ago. A strand of straw

was twisted into coarse rope, which, as it lengthened out, was coiled

(commencing at the top) into a conical-shaped hive. The coils were bound

together, as the hive took shape, with cords or strips of elm bark. This

kind of hive, although light, was lasting and made a warm home for the

bees during the long winter months. Baskets of all sizes were made of

straw on the same principle at the farm houses. Such straw work was both

strong and durable and, if well made, would outlast the Indian or splint

baskets. Among the Pennsylvania Dutch conical-shaped baskets made of straw

were used for raising their bread in.

Milking Time.

Nowadays on the farm hired men mostly do the milking,

the women usually having enough to do in the house, but years ago it was

as much a woman's work, if not more so than a man's, to do the milking.

About milking time might be seen the housewife with a sunbonnet or a

colored handkerchief tied over her head and several pails in her hand

hieing away to the barnyard to milk the cows. After the milk had been

emptied out of the pails, the latter were washed out and placed upside

down on the pickets of the garden fence to dry. We can see now, in

imagination, the grandmother, as she sat on the three-legged stool

milking, and, as Brindle switched her tail or moved her leg to shake off

some offending fly, nearly putting her foot into the pail or upsetting it,

we can hear grandmother saying, "So, bossie, so." Each milker had certain

cows to milk, it being thought that a cow would not yield its milk so

readily to a strange milker. It was the small boy's work to bring the cows

from the pasture field in the evening and take them back again in the

morning before going to school. He was generally accompanied back and

forth by the farm-house dog. The cows could be seen moving slowly toward

the bars in response to the familiar call of "Co, boss; co, boss; co, co,

co," those that lagged behind being brought up by the dog.

Plucking Geese.

The geese were generally plucked three or four times

during the year, or once in every seven weeks, commencing in the month of

June. In some places the practice is contrary to law, it being considered

as cruelty to animals, but in the early days it was very common, every

farmer keeping a flock of geese for this purpose. The plucking was done by

the women,* the down being made into pillows and feather ticks. Among the

Germans and Pennsylvania Dutch it was the custom, as a matter of economy

and comfort in the winter time, to have a feather tick on top instead of

quilts. To most of us, however, the greatest luxury in the way of a bed

was the old cord-bottomed bedstead, with its snugly- filled straw ticks,

woollen blankets and "patchwork" quilts. It was about as comfortable as

the modern spring mattress, although it had a tendency to sag in the

centre after it had been used a while. It was quite a feat for the small

children to clamber up the high sides of the tick when freshly filled with

straw. how father would stretch and strain as he tugged at the cords, or

with a stick or hammer handle twisted the round sides of the bed, in order

to screw it into the posts and so tighten the ropes attached to the knobs

on the outside of the rail when putting up the beds.

Soap Making.

We have previously mentioned that in our

grandfather's time nothing was wasted—everything was utilized. All scraps

of grease, fat, pork, rinds, etc., were thrown together in a box or barrel

until sufficient had been collected for making a batch of soap. This had

to be made in the right time of the moon, otherwise the soap would shrink

and not be so bulky, at least so our superstitious forefathers thought.

The lye used in making soap was obtained in plenty from hardwood ashes.

The ash leach was usually a permanent fixture in some out-of-the-way

corner of the back yard. Sometimes it was made out of a length of a hollow

basswood log, and also by knocking the bottom out of a barrel and setting

it on a board raised up from the ground several feet, and tilted so as to

carry off the lye, by a groove in the board, into a crock or pail placed

underneath. In the leach was placed, first, a layer of straw, then a

quantity of lime, and on that the ashes. Water was next poured on, which,

as it soaked through, dissolved the alkaline salt (caustic potash). The

making of a batch of soap usually occupied a whole day, from early morn

till late at night. A pole was hung on several crotched sticks placed in

the ground a few feet apart; on this the large iron kettle full of lye and

grease was placed and a brisk fire built underneath.

There were two kinds of soap—hard and soft. If hard soap was to be made it

required more boiling than for soft, besides the addition of a little salt

and resin.

In regard to the superstition as

to the time of the moon in which the soap had to be made, we might say it

is doubtful whether there is really anything in it, notwithstanding that

many people still hold to the belief. A soap manufacturer of many years'

experience told the writer that he paid no attention whatever to the moon

when making soap. This ought to be proof enough that the old idea is a

fallacy.

Potash.

Among the 'settlers the making of

potash was quite an industry, as it is yet in some of the backwoods

settlements. The ashes of the hardwood logs, after the log-heaps had been

burnt up, were gathered together and put into large wooden leaches. The

lye which was obtained was evaporated by boiling to obtain the residue,

which was crude potash. Great heat was necessary to boil down the lye. The

potash industry was quite a source of revenue to the pioneers. Quantities

were shipped to Montreal, where a fair price was obtained.

Cheese Making.

Nowadays, here and there through

the country, we find cheese factories. A wagon is sent round every morning

to collect the big cans of milk, which are filled after milking and left

standing on platforms by the roadside at the front of the farm. In the

early days there were no cheese factories, and therefore the farmers had

to make their own cheese. Usually this work was done by the women. The

ordinary or English cheese was made in the following manner: First, a calf

was killed, the stomach was taken out, rinsed off, and dried for the sake

of the rennet (pepsin) which it contained. The sweet milk was brought to

blood-heat, and a solution, made from small pieces of the rennet, added,

when the curd formed would separate. The whey was then drained off, the

curd cut up fine, seasoned with salt, and put in a lever-press (afterwards

screw), which removed the balance of the whey and pressed the curd into a

solid block of cheese. A cloth was then placed around each cheese, after

which it was set away until it was cured enough to be ready for use.

Among the German settlers it was

customary to make the sour milk into different kinds of cheese. One of the

most common kinds was the "schmier kase," or sour curd cheese, made by

taking sour milk after it had become thick, subjecting it to moderate

heat, or scalding it slightly, when the solid part of the milk would

separate from the whey; it was then put into a cloth bag and hung up to

drain. This kind of cheese, introduced by the Pennsylvania German

settlers, became popular among all classes living in the vicinity of the

German settlements. It is a wholesome and delicious article of diet.

Usually cream was added when made ready for the table.

The "hand kase," or bail cheese,

was made by taking the same cheese, seasoning it with salt and butter, and

then rolling it by the hand into balls, and laying it away to ripen or

cure.

The pot cheese was made by taking

the sour curd cheese, packing it in a crock after seasoning, and setting

it away in a warm place to decay or ripen. Among the Germans it was

greatly relished. The odor from it was not unlike that of the famous

"Limburger," and to a person unaccustomed to it was rather offensive.

How Sauer Kraut was Made.

A certain medical writer has

called sauer kraut "rotten cabbage." Even though it may be cabbage in a

somewhat putrid or fermented state, and unfit food for persons with weak

digestion, it certainly served a helpful purpose on the bill of fare of

the early settler, especially in the winter time, when green vegetables

and fresh meats were scarce. It was rightly considered a preventative of

scurvy, and for that reason is generally laid in stock by sailors and

soldiers who expect to have to subsist for any length of time on salted

provisions. The Germans are credited with being the originators of this

article of diet, and even now among them its use is more common than among

other classes of people.

The usual method of preparing

sauer kraut by our forefathers was as follows: in the afternoon the

cabbage was gathered and brought into the house, and in the evening it was

trimmed of its outer leaves and cut fine. Some would use a bright clean

spade for cutting it up, but most folks had a board with knives fitted in,

the sharp edge of the knives projecting slightly as in a plane. On this a

box without a bottom, raised up above the knives by cleats at the sides of

the board, was placed. The board being placed over the top of an empty

barrel, the box was filled with cabbage, and as it was run back and forth

over the board the cabbage was cut into shreds and dropped into the barrel

beneath. The cabbage was arranged in the barrel in layers, with a goodly

quantity of salt between each layer. After the barrel was filled the

cabbage was stomped down with a wooden stomper, then covered with boards,

on which were placed heavy stones, when it was left for several weeks or a

month to ferment or become sour, when it was ready for use. In order to

keep the sauer kraut from spoiling, the brine which formed was always

supposed to cover the cabbage. Among the Old Country Germans it is said

(although the veracity of the statement has never been vouched for) that

the cabbage was stomped down with the bare feet. This should be no

detriment to the cabbage; provided the feet were clean.

In pressing the grape in the wine

countries of Europe the help of the naked feet is resorted to, and the

wine is none the worse of the process. But still the weight of evidence is

against the belief that this practice has ever been adopted in preparing

cabbage for sauer kraut.

|