|

ALTHOUGH the weavers dealt separately with the

manufacturers for each piece of work, there were some general lists of rates

to be maintained against the more selfish of the employers, and hence the

Weavers' Trade Union arose. Many a fierce struggle they had with the

manufacturers, more or less successful. In one of these contests over what

was called the "sma'" shot, they gained a notable victory, which they

commemorated by instituting a holiday under the name of "Sma' Shot

Saturday." The "sma' shot," as already explained, was a binding thread not

included in the design but necessary for making a perfect fabric. The

masters did not wish to pay for this, but the weavers stoutly held to their

demand and were successful. This holiday was instituted in 1856 and is still

celebrated on the first Saturday of July, although "sma' shots" are no

longer used, or even understood in Paisley.

Many of the men who began life as weavers rose to be manufacturers, and also

obtained civic distinction in the town. Politics absorbed much of the

weavers' attention. They were all Reformers in those days and strong

Radicals, with even a considerable leaning to Socialism, but always vigorous

and intelligent. It was a common saying that the weavers of the First Ward

(the West End) "gave the tone of politics to Europe;" and no doubt some of

them believed it, or something near it. Sir Daniel K. Sandford was Member of

Parliament for Paisley in 1834, and, on retiring, gave it as his experience

that, for Paisley to be adequately represented, there would have to be a

Member for every weaver's shop in the town.

The weavers took part in the Radical Movement, which came on after the

conclusion of the Napoleonic wars, and was to some extent a consequence of

these events. One of their leaders was John Henderson, a cutler to trade,

who, it has been said, escaped to America concealed in a herring barrel. It

is characteristic that, after the affair blew over, he returned, and

subsequently became Provost of the town. Provost Henderson was a Quaker, and

a cultured and much-esteemed man, and at one time edited the Paisley section

of the Reformers' Gazelle. He was Provost during the great depression of

trade in 1841-2, when the town became bankrupt, and worked hard to alleviate

the distress of that unfortunate time.

Some

good stories are told of the weavers during the Radical time. They were all

"agin the Government" in those days, and at one time a general rising was to

take place. One ingenious weaver was reported to have invented a "boo't

gun," which was to do great destruction upon the "sogers," while the users

were safe. The present generation will have to be told that a "boo't" gun,

was a gun that could shoot round a corner!

It is told of another weaver, who kept the roll of

the conspirators, that when called upon by his comrades to produce it,

confessed that he had burned it, because, said he, "I wis telt that if the

sogers fan it on me, they wad chap aff my heid like a sybo," and that

although the loss of his head would be no loss to the cause, "it wad be a

sair loss tae him." And no doubt it would, yea an irreparable loss.

The "beaming shops" were the great places of meeting

for the weavers, when the affairs of the State were to be discussed, and the

inevitable "committee with power to add to their number" appointed, which

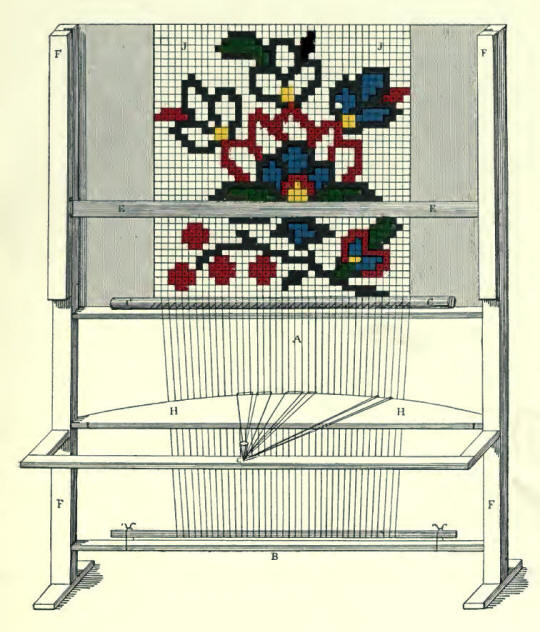

was to carry Out the decisions of the meeting. When the weaver gets a web

from the manufacturer, it is in the form of a chain, rolled up in a ball.

The first process is to spread it properly on a beam. This is done in the

beaming shop, and necessitates a considerable clear length of floor. Such a

room, lit up by a dozen "crusies," formed the favourite place of meeting.

Here were spent many happy nights. Here debate ran high, and burning

eloquence was poured forth, and men received a real education, which it is

to be feared the present generation of working men can scarcely obtain.

The writer, as a boy, took immense delight if by any

chance he could manage to gain access to these weavers' meetings, and now

through the mists of years, looks back on these rare occasions as not the

least enjoyable and instructive hours of his life. Some of the weavers were

good speakers, and could enrich their discourses with appropriate allusions

and quotations, especially from the poets, of whom they were particularly

fond. Sometimes a less well-informed speaker would get hold of a "

lang-nebbit " word which he would introduce so often as to provoke

merriment, and have it fastened upon him as a nick-name. Many of these

nick-names were very amusing, and not unkindly. One frequent speaker who was

accustomed to straighten up a subject, when the discussion got a trifle

"ravelled," as was often the case, acquired the name of "Clearhead." Another

worthy, not being able to tackle the big word "Constantinople," pronounced

it so like S "scones-tied-in-a-napkin," that this name stuck to him for the

rest of his life.

The comic element and a

pawky style of expression that was peculiar to the weavers, were never

absent, but were always employed with the utmost good humour. The weavers

knew how to conduct public business with decorum, and no rows ever took

place. At one meeting an obstinate weaver insisted on keeping his hat on,

notwithstanding the protests of the meeting. This was speedily brought to an

end by the sarcastic remark, "Let the puir man alane, d'ye no see he has got

the scaw?" and off went the hat immediately, as the only way of proving that

the owner did not suffer from that disease. This adroit sally was received

with roars of laughter.

When the Chartist agitation began, the weavers threw

themselves into it with characteristic ardour. The meetings at that time

were usually held in the Old Low Church in New Street. Here Daniel O'Connell

held forth in 1835, on which occasion that pugnacious divine, the Reverend

Patrick Brewster, got into a notoriety which lasted through life. Many

stirring scenes took place in this hail, which is now classic ground to

every old Paisley man.

A leader among the

weavers in those days was Robert Cochran. Although more renowned as a

speaker than as a weaver, Mr. Cochran, in later life, by the aid of his

family, established a thriving drapery trade. He continued to take an active

interest in the affairs of the burgh, and after many years of municipal

labour, attained the distinction of being Provost of his native town.

In religious matters, also, the weavers had ways of

their own. They were in the main a devout and serious class, and much given

to theological discussions. Sunday was well observed. The streets were

singularly quiet, and the sweet sounds of family worship could be heard in

the morning from nearly every house. The staid character of the weavers was

not unmixed with a little humour. A weaver of this very solemn and serious

order was groaning over a bad web that sorely tried his patience, and was

sympathised with by a neighbour, who remarked, "Puir John, ye ken he daurna

swear," which would no doubt have relieved his feelings. As was natural,

they were nearly all dissenters; indeed, they had a tendency to set up

little kirks of their own. This phase of the character of the weavers of

Paisley is described with much delightful detail in The Pen Folk of the late

Mr. David Gilmour. Paisley is fortunate in having had an author, who in such

graphic sketches, has immortalized the condition and peculiarities of the

harness weavers. |