|

THE shawl was woven face downwards. To the weaver

there appeared only a mass of floating threads, without form and void. Close

attention on the part both of weaver and draw-boy was thus necessary every

moment, in order to prevent any false shot from passing in to mar the

design. The weaver had another constant care

before him. Every inch that he wove must measure to the minutest fraction,

neither more nor less, than the precise space allotted by the design. This

perfect accuracy arose because of the necessity that a plaid of three or

four yards in length must terminate within a quarter of an inch of its

stipulated length. The former reference to the mode of dyeing or staining

the warps will make this obvious.

How much

skill and delicacy of touch was required will be plain to every reader. As

an aid to guide him, the weaver usually passed a pin through the cloth, and

carefully measured each three or four inches, knowing, as he did, that 100

or a 1,000 shots ought to measure a definite length, or complete so much of

the design. And it must be acknowledged to be a triumph of weaving, that in

a plaid measuring three or four yards in length, with six or seven colours

running, and a heavy box-lay to handle, the plaid should be brought to a

perfect finish within a quarter of an inch of its assigned limit.

The lay in common use was one of ten boxes, with a drop

motion controlled by a trigger under the weaver's thumb, so that he could

raise or drop each box in succession, or skip one or more as required. Thus,

if eight colours formed the design, it might happen that colour 3 in the

gamut of colours was silent in a particular bridle. The draw-boy would see

this by a gap being left, and call out "miss ane;" the weaver would then

drop box 3 and pass to the fourth colour. When the completed shots of each

bridle had passed through, then would follow the ground shot; but as this

was often a heavy lift, too much for a boy to raise, he had the control of a

strong wooden lever, moving on a spindle, called the "deil" or "douge."

Pressing this against the simple, the heavy lift was thus made, and the

ground shots were passed through.

The ground

colour of the fabric was generally fine Thibet wool (Botany worsted), and

being of a smaller count or thinner thread than the spotting or figure

colours, there were usually two or more shots put in for one of the spotting

colours, the threads of which were always thicker. The bridle was therefore

composed of, say two ground shots, one of each of the spotting colours, and

then a shot of fine lace cotton. This is the "sma' shot" which is

commemorated in the holiday, as explained further on. The small shot acted

as a binder for all the other colours, and was not intended to be seen. It

was put through a shed formed by the weaver with heddles continuous across

the width of the warp, and not by any action of the draw-boy. The ground or

back lash was formed by the boy drawing Out all the lashes of a bridle with

the left hand and passing in the "deil" with the right hand. Pushing it back

with all that remained of the simple, he raised the ground shed, which had

to be held up for two shots, the weaver forming the twill by treading the

heddles. It was arduous work for a young boy,

requiring continuous attention, as a mistake on his part might work havoc on

the design. Like his master, he too needed a careful touch. Lash number x

might represent only a few threads of the simple, and so a light touch was

needed to make the required shed. Lash number 5 might need all his strength

to draw it down and so make a clear passage for the shuttle. If the weaver

were harsh and exacting, the poor boy was in constant fear lest a slip might

be made. But even under a kindly master, the work was heavy, and often the

hours were long, running sometimes near to midnight on occasional

emergencies. In cold weather his bare feet would be nestled within his

Kilmarnock bonnet, resting on- the clay floor. And yet these boys were a

brave cheery race, full of fun and mischief, and ready for any ploy when the

web was out, or the "maister" gone for a day to the fishing or curling, or

mayhap on the "spree." Indeed, the draw-boys rather preferred a master who

occasionally enjoyed himself "not wisely but too well." Not a few of these

draw-boys rose to positions of influence in the old country, and in the

"Greater Britain" beyond the seas. Peace be to their memory.

In the way

we have endeavoured to describe, the old weavers made beautiful and perfect

productions. It would be difficult now to find handicraft workers to exhibit

such patience, skill, and devotion. It was severe work, both for man and

boy. Verily the workers of our day have a lighter lot to face. But these old

weavers had some compensations. Out of the travail of this drudgery, was

born the patient industry, the intellectual strength, the cultured taste,

and that love of beauty in fabrics, in nature, and in song, which marked the

weavers of Paisley.

Although the weaving of

the Harness Shawl was a delicate operation, and had a highly educative

effect on the workman, there were many preparatory and subsidiary

occupations connected with the shawl manufacture, where highly skilled

labour was also required. No weaver, however wide his knowledge and

experience, could undertake the whole of these operations, and thus

specialists arose for every department. This was an important point in the

spread of the very high intellectual training, which the Harness Shawl

trade, above many other occupations, was instrumental in promoting.

The designing was a very special department, and

demanded a wide culture. Designing for a garment that is to be draped on the

figure, differs materially from that destined for a wall-paper or a carpet.

A good shawl designer had not only to be a careful student of Indian art,

and of design in general, he had also to understand the limits which a loom

imposes on design, and to know the number of warp threads which the harness

could control, and so construct his pattern that it would be possible to

produce it on the loom that then existed, and at a price that would command

the market. Thus the designers requiring in addition to their artistic

skill, to possess considerable technical knowledge, were quite a superior

class of operatives.

Dyeing was equally

important, and required highly skilled workmen. From the necessity of having

the parti-coloured finish on the border, and different coloured portions

through all the length of the warp, dyeing became practically a system of

printing, and had to be most carefully done. Men were thus trained in

handicraft to a degree of skill, and with an intelligence that has very

little counterpart in many of our present industries. To enable the dyer to

properly stain or print the warp, the warping had to be so carefully done as

to create another class of specialists known as warpers. The kind of work to

which these men devoted themselves required the utmost delicacy. One of the

most exacting parts of the manufacturer's duty was the drawing of the dyeing

plan, so as to guide correctly both the warpers and the dyers.

The placing of such a stained warp on the beam ready

for the weaver, was the work of the beamers, and this also required a

specially trained class of men, who entirely devoted themselves to this

operation. The stained portions had to be placed accurately at their proper

place. Certain little flaws might be afterwards remedied with a paint brush,

but any material error in the beaming would produce a damaged plaid, hence

this important operation came to be a special industry.

Designing, warping, staining, and beaming were

operations outside of the loom, and none of the weavers undertook any part

of these operations. But in the loom, the harness-tying and the entering

were occasionally done by the weaver himself, if he were competent, but in

most cases these matters were confided to specialists. Harness-tiers thus

became a separate class of operatives, who had great skill in this work and

could do it much quicker than any weaver. Entering the web, that is, passing

each thread through its proper eye in the mail or heddle, became a distinct

profession of the enterers, who were much more expert at this delicate and

responsible operation than any weaver could be.

The work of the flower-lasher, also, formed a separate

profession. This subdivision of labour not only produced the best work, but

it widely extended the culture of the operatives.

Even when the shawl came out of the loom, it had to go

to professional clippers, to clear the under part of the loose threads, a

work that had to be confided to specially trained hands. The clipping

machine was a framework carrying a set of steel blades, which revolved at a

great speed, under which the shawl was passed several times, each closer

than the preceding, till all the loose threads were cleanly shaven off. The

weight of the shawl would thus sometimes be reduced from one hundred ounces,

when it came out of the loom, to thirty four ounces, which was considered

the average weight for a good quality of plaid. It is evident that this

operation, although done by a machine, required an intelligent and skilful

-worker. The slightest error in the adjustment of the knives might destroy a

valuable plaid. Then followed the fringing,

finishing, and pressing of the shawls, which again employed people specially

trained to these matters. Thus all the workers connected with the

manufacture of the shawl had to be intelligent, patient, and skilful. The

work in all its branches contributed to form that cultured character which

marked the Paisley operative.

The Paisley

Shawl as now described, was woven on the draw-loom by the aid of the

draw-boy. The mechanism of this loom is shown in Plate 13.

Attempts were made as far back as 1728 to do the

draw-boy's work by means of perforated cards. This invention was perfected

by a French weaver, Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752-1834), in the machine which

bears his name, and which was first shown in i8oi. The French adopted it

much earlier than the Paisley weavers. Ultimately it made its way here, and

gradually superseded the draw-boy, who was rarely employed after 1850.

Mechanical improvements of this kind were inevitable

and desirable, yet the tendency of machinery is to alter entirely the type

of workman, and thus the old cultured and ingenious weaver gradually

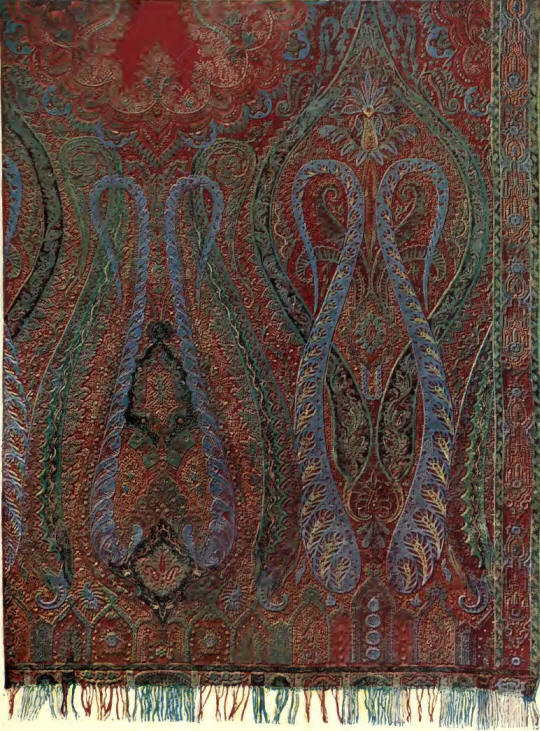

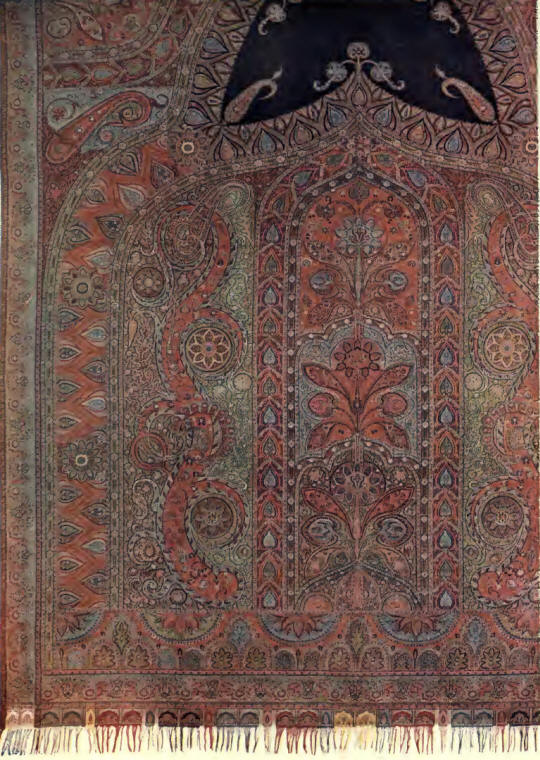

disappeared. Before leaving this subject, it

may be well to mention the introduction of the double or reversible shawl.

The harness shawl, as we have said, was woven face downwards, and the loose

threads at the back were cut off by a clipping machine, so that the pattern

was shown only on one side. In the reversible shawl, the warp and weft

threads were so arranged as to show a pattern on both sides, and no loose

ends required to be cut off. Mr. John Cunningham was principally concerned

in this invention. Plate 9 shows a shawl of this class. It will be observed

that the part folded over, is the same design as the lower portion, but with

the colours reversed.

Large numbers of

reversible shawls were made between i 86o and 1885, but the invention came

too late to give the inventor the reward which his ingenuity deserved. The

shawl as an article of dress went Out of fashion, and no improvements or

cheapening of production, could revive the demand. Even if fashion had not

changed, the hand-loom industry, which had so much to do with the

development of the peculiar character of the weavers of Paisley, was certain

to decay, in face of the general adoption of the power-loom. The great mass

of the public will always purchase in the end, the machine-made article

because of its cheapness.

|