|

IN an old-world town like St. Andrews the stately, old-

world Moral Philosophy Professor must have seemed wonderfully in his place.

There are men who, good- looking in youth, become 'ordinary- looking' in

later years, but Ferrier's looks were not of such a kind. To the last—of

course he was not an old man when he died —he preserved the same

distinguished appearance that we are told marked him out from amongst his

fellows while still a youth. The tall figure, clad in old-fashioned,

well-cut coat and white duck trousers, the close-shaven face, and merry

twinkle about the eye signifying a sense of humour which removed him far

from anything which we associate with the name of pedant; the dignity, when

dignity was required, and yet the sympathy always ready to be extended to

the student, however far he was from taking up the point, if he were only

trying his best to comprehend—all this made up to those who knew him, the

man, the scholar, and the high-bred gentleman, which, in no ordinary or

conventional sense, Professor Ferrier was. It is the personality which, when

years have passed and individual traits have been forgotten, it is so

difficult to reproduce. The personal attraction, the atmosphere of culture

and chivalry, which was always felt to hang about the Professor, has not

been forgotten by those who can recall him in the old St. Andrews days; but

who can reproduce this charm, or do more than state its existence as a fact?

Perhaps this sort only comes to those whose life is mainly intellectual—who

have not much, comparatively speaking, to suffer from the rough and tumble

to which the 'practical' man is subjected in the course of his career.

Sometimes it is said that those who preach high maxims of philosophy and

conduct belie their doctrines in their outward lives; but on the whole, when

we review their careers, this would wonderfully seldom seem to be the case.

From Socrates' time onwards we have had philosophers who have taught virtue

and practised it simultaneously, and in no case has this combination been

better exemplified in recent days than in that of James Frederick Ferrier,

and one who unsuccessfully contested his chair upon his death, Thomas Hill

Green, Professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford. It seems as though it may

after all be good to speculate on the deep things of the earth as well as to

do the deeds of righteousness.

If the saying is true, that the happiest man is lie who

is without a history, then Ferrier has every claim to be enrolled in the

ranks of those who have attained their end. For happiness was an end to

Ferrier: he had no idea of practising virtue in the abstract, and finding a

sufficiency in this. He believed, however, that the happiness to be sought

for was the happiness of realising our highest aims, and the aim he put

before him he very largely succeeded in attaining. His life was what most

people would consider monotonous enough: few events outside the ordinary

occurrences of family and University life broke in upon its tranquil course.

Unlike the custom of some of his colleagues, summer and winter alike were

passed by Ferrier in the quaint old sea-bound town. He lived there largely

for his work and books. Not that he disliked society; he took the deepest

interest even in his dinner-parties, and whether as a host or as a guest,

was equally delightful as a companion or as a talker. But in his books he

found his real life; he would take them down to table, and bed he seldom

reached till midnight was passed by two hours at least. One who knew and

cared for him, the attractive wife of one of his colleagues, who spent ten

sessions at St. Andrews before distinguishing the Humanity Chair in

Edinburgh, tells how the West Park house had something about its atmosphere

that marked it out as unique—something which was due in great measure to the

cultured father, but also to the bright and witty mother and the three

beautiful young daughters, who together formed a household by itself, and

one which made the grey old town a different place to those who lived in it.

Ferrier, as we have seen, had many distinguished

colleagues in the University. Besides Professor Sellar, who held the Chair

of Greek, there was the Principal of St. Mary's (Principal Tulloch),

Professor Shairp, then Professor of Latin, and later on the Principal; the

Logic Professor, Veitch, Sir David Brewster, Principal of the United

Colleges, and others. But the society was unconventional in the extreme. The

salaries were not large: including fees, the ordinance of the Scottish

Universities Commission appointing the salaries of Professors in 186r,

estimates the salary of the professorship of Moral Philosophy at St. Andrews

at £444, 18s., and the Principal only received about Jjioo more. But there

were not those social customs and conventions to maintain that succeed in

making life on a small income irksome in a larger city. All were practically

on the same level in the University circle, and St. Andrews was not invaded

by so large an army of golfing visitors then as now, though the game of

course was played with equal keenness and enthusiasm. Professor Ferrier took

no part in this or other physical amusement: possibly it had been better for

him had he left his books and study at times to do so. The friend spoken of

above tells, however, of the merry parties who walked home after dining out,

the laughing protests which she made against the Professor's rash statement

(in allusion to his theory of percej5fion-mecum) that she was 'unredeemed

nonsense' without him; the way in which, when an idea struck him, he would

walk to her house with his daughter, regardless of the lateness of the hour,

and throw pebbles at the lighted bedroom windows to gain admittance— and of

course a hospitable supper; how she, knowing that a tablemaid was wanted in

the Ferrier establishment, dressed up as such and interviewed the mistress,

who found her highly satisfactory but curiously resembling her friend Mrs.

Sellar; and how when this was told her husband, he exclaimed, 'Why, of

course it's she dressed up; let us pursue her,' which was done with good

effect! All these tales, and many others like them, show what the homely,

sociable, and yet cultured life was like—a life such as we in this country

seldom have experience of: perhaps that of a German University town may most

resemble it. In spite of being in many ways a recluse, Ferrier was ever a

favourite with his students, just because he treated them, not with

familiarity indeed, but as gentlemen like himself. Other Professors were

cheered when they appeared in public, but the loudest cheers were always

given to Ferrier.

Mrs. Ferrier's brilliant personality many can remember

who knew her during her widowhood in Edinburgh. She had inherited many of

her father, 'Christopher North's' physical and mental gifts, shown in looks

and wit. A friend of old days writes: 'She was a queen in St. Andrews, at

once admired for her wit, her eloquence, her personal charms, and dreaded

for her free speech, her powers of ridicule, and her withering mimicry.

Faithful, however, to her friends, she was beloved by them, and they will

lament her now as one of the warmest-hearted and most highly-gifted of her

sex.' Mrs. Ferrier never wrote for publication,—she is said to have scorned

the idea,—but those who knew her never can forget the flow of eloquence, the

wit and satire mingled, the humorous touches and the keen sense of fun that

characterised her talk; for she was one of an era of brilliant talkers that

would seem to have passed away. Mrs. Ferrier's capacity for giving

appropriate nicknames was well known: Jowett, afterwards Master of Balliol,

she christened the 'little downy owl.' Her husband's philosophy she

graphically described by saying that 'it made you feel as if you were

sitting up on a cloud with nothing on, a lucifer match in your hand, but

nothing to strike it on,'—a description appealing vividly to many who have

tried to master it!

In many ways she seemed a link with the past of bright

memories in Scotland, when these links were very nearly severed. Five

children in all were born to her; of her sons one, now dead, inherited many

of his father's gifts. Her elder daughter, Lady Grant, the wife of Sir

Alexander Grant, Principal of the Edinburgh University and a distinguished

classical scholar, likewise succeeded to much of her mother's grace and

charm as well as of her father's accomplishments. Under the initials 'O. J.'

she was in the habit of contributing delightful humorous sketches to

Blackwood's Magazine—the magazine which her father and her grandfather had

so often contributed to in their day; but her life was not a long one: she

died in 1895, eleven years after her husband, and while many possibilities

seemed still before her.

Perhaps we might try to picture to ourselves the life

in which Ferrier played so prominent a part in the only real University town

of which Scotland can boast. For it is in St. Andrews that the traditional

distinctions between the College and the University are maintained, that

there is the solemn stillness which befits an ancient seat of learning, that

every step brings one in view of some monument of ages that are past and

gone, and that we are reminded not only of the learning of our ancestors, of

their piety and devotion to the College they built and endowed, but of the

secular history of our country as well. In this, at least, the little

University of the North has an advantage over her rich and powerful rivals,

inasmuch as there is hardly any important event which has taken place in

Scottish history but has left its mark upon the place. No wonder the love of

her students to the Alma Mater is proverbial. In Scotland we have little

left to tell us of the medieaval church and life, so completely has the

Reformation done its work, and so thoroughly was the land cleared of its

'popish images'; and hence we value what little there remains to us all the

more. And the University of St. Andrews, the oldest of our seats of

learning, has come down to us from medieval days. It was founded by a

Catholic bishop in 1411, about a century after the dedication of the

Cathedral, now, of course, a ruin. But it is to the good Bishop Kennedy who

established the College of St. Salvator, one of the two United Colleges of

later times, that we ascribe most honour in reference to the old foundation.

Not only did he build the College on the site which was afterwards occupied

by the classrooms in which Ferrier and his colleagues taught, but he

likewise endowed them with vestments and rich jewels, including amongst

their numbers a beautifully chased silver mace which may still be seen. Of

the old College buildings there is but the chapel and janitor's house now

existing; within the chapel, which is modernised and used for Presbyterian

service, is the ancient founder's tomb. The quadrangle, after the

Reformation, fell into disrepair, and the present buildings are

comparatively of recent date. The next College founded—that of St.

Leonard—which became early imbued with Reformation principles, was, in the

eighteenth century, when its finances had become low, incorporated with St.

Salvator's, and when conjoined they were in Ferrier's time, as now, known as

the 'United College.' Besides the United College there was a third and last

College, called St. Mary's. Though founded by the last of the Catholic

bishops before the Reformation, it was subsequently presided over by the

anti-prelatists Andrew Melville and Samuel Rutherford. St. Mary's has always

been devoted to the study of theology.

But the history of her colleges is not all that has to

be told of the ancient city. Association it has with nearly all who have had

to do with the making of our history— the good Queen Margaret, Beaton, and,

above all, Queen Mary and her great opponent Knox. The ruined Castle has

many tales to tell could stones and trees have tongues—stories of bloodshed,

of battle, of the long siege when Knox was forced to yield to France and be

carried to the galleys. After the murder of Archbishop Sharp, and the

revolution of 1688, the town once so prosperous dwindled away, and decayed

into an unimportant seaport. There is curiously little attractive about its

situation in many regards. It is out of the way, difficult of access once

upon a time, and even now not on a main line of rail, too near the great

cities, and yet at the same time too far off. The coast is dangerous for

fishermen, and there is no harbour that can be called such. No wonder, it

seems, that the town became neglected and insanitary, that Dr. Johnson

speaks of 'the silence and solitude of inactive indigence and gloomy

depopulation,' and left it with 'mournful images.' But if St. Andrews had

its drawbacks, it had still more its compensations. It had its links—the

long stretch of sandhills spread far along the coast, and bringing crowds of

visitors to the town every summer as it comes round; and for the pursuit of

learning the remoteness of position has some advantages. Even at its worst

the University showed signs of its recuperative powers. Early in the century

Chalmers was assistant to the Professor of Mathematics, and then occupied

the Chair of Moral Philosophy (that chair to which Ferrier was afterwards

appointed), and drew crowds of students round him. Then came a time of

innovation. If in 1821 St. Andrews was badly paved, ill-lighted, and

ruinous, an era of reform set in. New classrooms were built, the once

neglected library was added to and rearranged, and the town was put to

rights through an energetic provost, Major, afterwards Sir Hugh, Lyon

Playfair. He made 'crooked places straight' in more senses than one, swept

away the 'middens' that polluted the air, saw to the lighting and paving of

the streets, and generally brought about the improvements which we expect to

find in a modern town. 'On being placed in the civic chair, he had found the

streets unpaved, uneven, overgrown with weeds, and dirty; the ruins of the

time-honoured Cathedral and Castle used as a quarry for greedy and

sacrilegious builders, and the University buildings falling into disrepair;

and he had resolved to change all this. With persistency almost unexampled,

he had employed all the arts of persuasion and compulsion upon those who had

the power to remedy these abuses. He had dunned, he had coaxed, he had

bantered, he had bargained, he had borrowed, he had begged; and he had been

successful. In 1851 the streets were paved and clean, the fine old ruins

were declared sacred, and the dilapidated parts of the University buildings

had been replaced by a new edifice. And he—the Major, as he was called—a

little man, white-haired, shaggy-eyebrowed, blue-eyed, red- faced, with his

hat cocked on the side of his head, and a stout cane in his hand, walked

about in triumph, the uncrowned king of the place.'

Of this same renovating provost, it is told that one

day he dropped in to see the Moral Philosophy Professor, who, however deeply

engaged with his books, was always ready to receive his visitors. 'Well,

Major, I have just completed the great work of my life. In this book I claim

to make philosophy intelligible to the meanest understanding.' Playfair at

once requested to hear some of it read aloud. Ferrier reluctantly started to

read in his slow, emphatic way, till the Major became fidgety; still he went

on, till Playfair started to his feet. 'I say, Ferrier, do you mean to say

this is intelligible to the meanest understanding?' 'Do you understand it,

'Major?' 'Yes, I think I do.' 'Then, Major, I'm satisfied.'

Of the social life, Mrs. Oliphant says in her Life of

Princiz5al 7'ulloth: 'The society, I believe, was more stationary than it

has been since, and more entirely disposed to make of St. Andrews the

pleasantest and brightest of abiding-places. Sir David Brewster was still

throned in St. Leonard's. Professor Ferrier, with his witty and brilliant

wife—he full of quiet humour, she of wildest wit, a mimic of alarming and

delightful power, with something of the countenance and much of the genius

of her father, the great "Christopher North" of Blackwood's Magazine—made

the brightest centre of social mirth and meetings. West Park, their pleasant

home, at the period which I record it, was ever open, ever sounding with gay

voices and merry laughter, with a boundless freedom of talk and comment, and

an endless stream of good company. Professor Ferrier himself was one of the

greatest metaphysicians of his time—the first certainly in Scotland; but

this was perhaps less upon the surface than a number of humorous ways which

were the delight of his friends, many quaint abstractions proper to his

philosophic character, and a happy friendliness and gentleness along with

his wit, which gave his society a continual charm.' Professor Knight, who

now occupies Ferrier's place in the professoriate of St. Andrews, in his

Life of Professor Shairp, quotes from a paper of reminiscences by Professor

Sellar: 'The centre of all the intellectual and social life of the

University and of the town was Professor Ferrier. He inspired in the

students a feeling of affectionate devotion as well as admiration, such as I

have hardly ever known inspired by any teacher; and to many of them his mere

presence and bearing in the classroom was a large element in a liberal

education. By all his colleagues he was esteemed as a man of most sterling

honour, a staunch friend, and a most humorous and delightful companion.

There certainly never was a household known to either

of us in which the spirit of racy and original humour and fun was so

exuberant and spontaneous in every member of it, as that of which the

Professor and his wife—the most gifted and brilliant, and most like her

father of the three gifted daughters of "Christopher North "—were the heads.

Our evenings there generally ended in the Professor's study, where he was

always ready to discuss, either from a serious or humorous point of view

(not without congenial accompaniment), the various points of his system till

the morning was well advanced.'

Ferrier's daughter writes of the house at West Park: It

was an old-fashioned, rough cast or "harled" house standing on the road in

Market Street, but approached through a small green gate and a short avenue

of trees--trees that were engraven on the heart and memory from childhood.

The garden at the back still remains. In our time it was a real

old-fashioned Scotch garden, well stocked with "berries," pears, and apples;

quaint grass walks ran through it, and a summer-house with stained- glass

windows stood in a corner. West Park was built on a site once occupied by

the Grey Friars, and I am not romancing when I say that bones and coins were

known to have been discovered in the garden even in our time. Our home was

socially a very amusing and happy one, though my father lived a good deal

apart from us, coming down from his dear old library occasionally in the

evenings to join the family circle.' This family circle was occasionally

supplemented by a French teacher or a German, and for one year by a certain

Mrs. Huggins, an old ex-actress who originally came to give a Shakespeare

reading in St. Andrews, and who fell into financial difficulties, and was

invited by the hospitable Mrs. Ferrier to make her home for a time at West

Park. The visit was not in all respects a success, Mrs. Huggins being

somewhat exacting in her requirements and difficult to satisfy. So little

part did its master take in household matters that it was only by accident,

after reading prayers one Sunday evening, that he noticed her presence. On

inquiring who the stranger was, Mrs. Ferrier replied, 'Oh, that is Mrs.

Huggins.' 'Then what is her avocation?' 'To read Shakespeare and draw your

window-curtains,' said the ever-ready Mrs. Ferrier! The children of the

house were brought up to love the stage and everyone pertaining to it, and

whenever a strolling company came to St. Andrews the Ferriers were the first

to attend their play. The same daughter writes that when children their

father used to thrill them with tales of Burke and Hare, the murderers and

resurrectionists whose doings brought about a reign of terror in Edinburgh

early in the century. As a boy, Ferrier used to walk out to his

grandfather's in Morningside—then a country suburb—in fear and trembling,

expecting every moment to meet Burke, the object of his terror. On one

occasion he believed that he had done so, and skulked behind a hedge and lay

down till the scourge of Edinburgh passed by. In 1828 he witnessed his

hanging in the Edinburgh prison. Professor Wilson, his father-in-law, it may

be recollected, spoke out his mind about the famous Dr. Knox in the Nodes as

well as in his classroom, and it was a well-known fact that his favourite

Newfoundland dog Brontė was poisoned by the students as an act of

retaliation.

Murder trials had always a fascination for Ferrier. On

one occasion he read aloud to his children De Quincey's essay, 'Murder as a

Fine Art,' which so terri6ed his youngest daughter that she could hardly

bring herself to leave her father's library for bed. Somewhat severe to his

sons, to his daughters Ferrier was specially kind and indulgent, helping

them with their German studies, reading Schiller's plays to them, and when

little children telling them old-world fairy tales. A present of Grimm's

Tales, brought by her father after a visit to London, was, she tells us, a

never-to-be-forgotten joy to the recipient.

The charm of the West Park house was spoken of by all

the numerous young men permitted to frequent its hospitable board. There was

a wonderful concoction known by the name of 'Bishop,' against whose

attraction one who suffered by its potency says that novices were warned,

more especially in view of a certain sunk fence in the immediate vicinity

which had afterwards to be avoided. The jokes that passed at these

entertainments, which were never dull, are past and gone,—their piquancy

would be gone even could they be reproduced,—but the impression left on the

minds of those who shared in them is ineffaceable, and is as vivid now as

forty years ago.

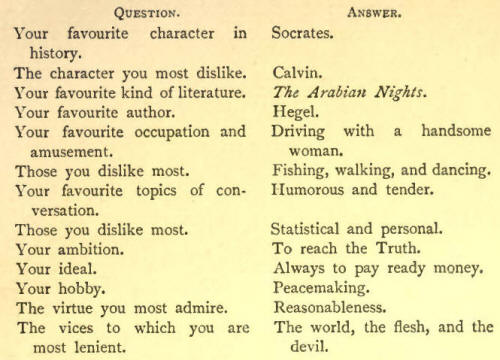

There was a custom, now almost extinct, of keeping

books of so-called 'Confessions,' in which the contributors had the rather

formidable task of filling up their likes or dislikes for the entertainment

of their owners. In Mrs. Sellar's album Ferrier made several interesting

'confessions '—whether we take them au grand serleux or only as playful

jests with a grain of truth behind. Here are some of the questions and their

answers.

These last two answers are very characteristic of

Ferrier's point of view in later days. He was above all reasonable—no

ascetic who could not understand the temptations of the world, but one who

enjoyed its pleasures, saw the humorous side of life, appreciated the

asthetic, and yet kept the dictates of reason ever before his mind. And his

ambition to reach the Truth.

'Differed from a host

Of aims alike in character

and kind,

Mostly in this—that in itself alone

Shall its reward be,

not an alien end

Blending therewith.'

Thus, like Paracelsus, he aspired. |