|

George

Cupples was born in 1822 at Legerwood manse,

Berwickshire, son of Free church minister George Cupples

(1786–1850). He was educated at Stirling and apprenticed

to a Liverpool shipowner. After an eighteen-month voyage

to India his indentures were cancelled and he studied

divinity at Edinburgh University. In 1858 he married

Anne Jane Douglas (1839–1898), daughter of Archibald

Douglas of the general post office in Edinburgh and

herself the author of fifty books for children. George

Cupples wrote dozens of nautical novels, such as The

Green Hand: A Sea Story (1856), The Two Frigates: or,

Captain Bisset's Legacy (1859), and Captain Herbert: A

Sea Story (1864). In addition, Cupples produced 254

tales and articles for Chambers's Edinburgh Journal,

Blackwood's Magazine, Fraser's Magazine, Macmillan's

Magazine, and others. Near the end of his life, his

literary friends presented Cupples with an annuity bond

of £30. He died in 1891 at the Admiralty House,

Newhaven.

The Green Hand

Anne Jane Cupples, née Douglas (4 January 1839 – 14 November 1896) was a Scottish writer and populariser of science. She was married to the dog-breeder and writer George Cupples, and after his death moved to be with her sisters in New Zealand, where she died in 1896. She wrote around fifty books in total, mostly intended for children, under the name Mrs George Cupples.

Norrie Seton

By Mrs George CupplesThe Adventures of Mark Willis

By Mrs George Cupples Genealogy

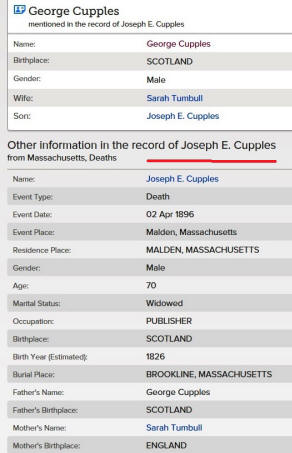

of George Cuppers

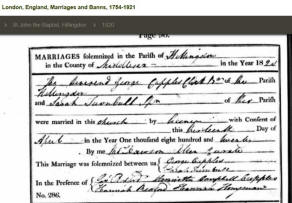

Marriage of George Cuppers

to Sarah Turnbull

1830's More Cuppers Births

1822 Birth of George Cupples

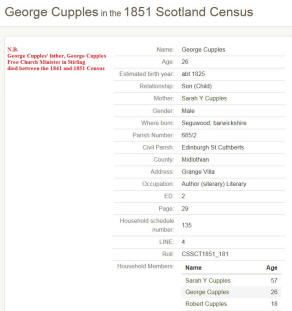

George Cupples in the 1851

census

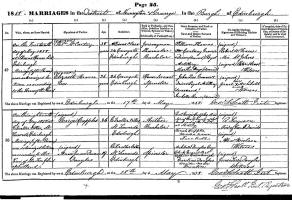

1858 Marriage of George

Cupples to Ann Jane Dunn Douglas

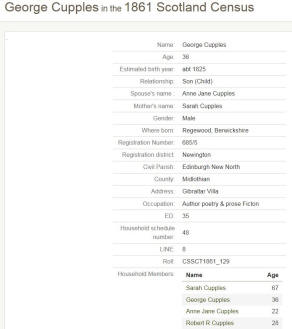

George Cupples in the 1861

Census

Death of Sarah Cupples

%20Cupples_small.jpg)

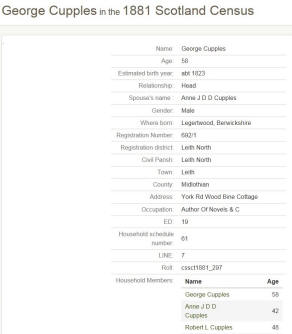

George Cupples in the 1881

Census

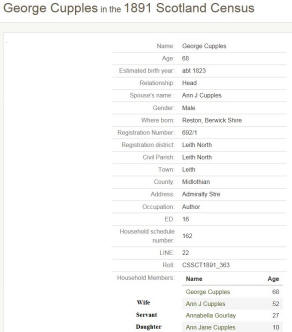

George Cupples in the 1891

Census

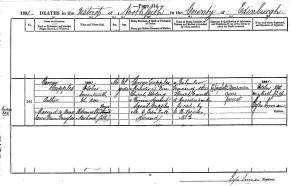

Death of George Cupples

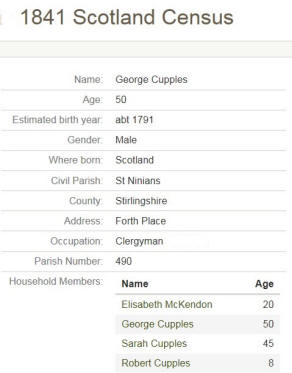

George Cupples 1841 Census

Cupples - Other Data

George

Cupples (1822–1891)

Critical and Biographical Introduction by Bartleby and

Company

George

Cupples was born at Legerwood, August 2nd, 1822, and

died October 7th, 1891. His father was a minister of the

Free Kirk, and his paternal ancestors had been

Calvinistic ministers for at least three generations. It

was natural that the young man should be intended for

the same profession, but he did not feel drawn to it,

and when about seventeen went to sea for two years.

Although of a firm physical constitution, the life of

the seaman wearied him, and he resumed his education at

the University of Edinburgh. He fell naturally into a

literary career, and though much of his work was

journalistic, he was reckoned in his day a critic of

true insight. His novels are his best title to

reputation, and show a vein of genuine creative power.

Cupples combined some of the sterling and attractive

traits of the cultured Scotchman of the period into a

genuine, manly, and winning personality. Though slightly

whimsical, his peculiarities were of the kind that

endear a man to his friends; and Cupples numbered among

his, Dr. John Brown, Dr. Stirling, Blackwood, and many

others of the cultivated Scotchmen of the period.

‘The

Green Hand,’ which came out in Blackwood from 1848 to

1851, is one of the best sea stories ever written. If we

put Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’ first for balance of

description and narration, and sureness in the character

touches, ‘The Green Hand’ and ‘Tom Cringle’s Log’ are

close seconds. Cupples’s book is perhaps slightly

overloaded with description, and deficient in technical

construction as a narrative; but it is nevertheless a

story which we read without skipping, for the

descriptive pages are highly charged with the poetic

element, and bear the unmistakable marks of being based

on actual observation. Life in a sailing vessel has

closer contact with the elemental moods of nature than

in a steamer, where the motive power is a mechanical

contrivance with the tiresome quality of regularity. To

be in alliance or warfare with the wind, and dependent

on its fitful moods, brought an element of variety and

interest into the seaman’s life which steam navigation,

with its steadily revolving screw and patent valves,

must always lack. Of this Cupples avails himself to the

fullest extent; and it would be difficult to find a

better presentation of the mysterious life and vastness

of the ocean, and of the subtle impression it makes on

those brought in daily contact with it, not excepting

Victor Hugo’s ‘Toilers of the Sea.’ This is due to the

fact that he spent two years before the mast when a

young man. Especially noticeable too is his admirable

use of adjectives denoting color, which are descriptive

because they image truly the observations of a man of

genius, and are not, as in so much modern writing,

purple patches sewed on without any real feeling for the

rich and subtle scheme of nature. In calling up to the

imagination the sounds of the sea,—the creaking of the

blocks, the wind in the rigging, the wash of the water

on the sides, the ripple on the bow, and the infinite

variety of the voice of the waves,—Cupples shows true

poetic power. It is not too much to say that ‘The Green

Hand’ does not suffer from the fact that one of the

parts stands in the magazine in juxtaposition to De

Quincey’s ‘Vision of Sudden Death.’

‘Kyloe

Jock and the Weird of Wanton-Walls’ is a transcript from

the boy life of the author. It appeared in Macmillan’s

Magazine, in the autumn numbers of 1860. It is but a

short sketch of a group of simple people in a secluded

border parish, but the quality of the writer is shown as

well in small things as in great ones. In it the wintry

scenes especially are given with broad and sure touches,

for the author is a genuine lover of nature; but the

characters of Kirstie the nurse, and of Kyloe Jock, the

half-savage herd-boy who knows so well the wild

creatures of the woods and fields that he has even given

names to the foxes, show the feeling for human nature

and the ability to embody it which marks the artist.

Kyloe Jock’s Scotch is said to be an absolutely perfect

reproduction of the vernacular; and it might be said

that this book, like some of our modern Scotch stories,

would be better if the dialect were not quite so good.

The

peculiar qualities of the author are not seen to such

good advantage in another book of his, ‘Scotch

Deerhounds and Their Masters.’ He was a breeder and

unquestioned authority on the “Grand Dog,” and

accumulated a store of curious information on its origin

and history; but his enthusiasm for this noble breed, or

“race” as he loves to call it,—and it certainly is the

finest and most striking of all the varieties of the

“friend of man,”—led him into some strange vagaries. One

would almost suspect him of holding the theory that dogs

domesticated man, so high does he rank them as agents of

early civilization. His etymology and his ethnology are

alike erratic. He holds that every ancient people in

whose name can be found the combinations “gal,” “alb,”

or “iber,” or any other syllable of a Celtic word, was

of the Celtic family, and that the Scotch deerhound and

the Irish greyhound are descendants of the primeval

Celtic dog. In this way he proves that the Carthaginians

and the shepherd kings of Egypt were undoubtedly Celts,

for their sculpture shows that they hunted with large

swift dogs that sprang at the throat of their prey. On

the other hand, every tribe that owned large clumsy dogs

that barked is probably non-Celtic. Mr. Cupples’s

contempt for such dogs is too intense for definite

statement, and he evidently thinks that the tribe that

owns them cannot hope to rise very high in the scale of

civilization. This is certainly Philo-Celticism run mad,

and is the more remarkable because Mr. Cupples could

discover no Celtic strain in his own ancestry. He gave

his dogs, however, Celtic names, as Luath, Shulach,

Maida, Morna, Malvina, Oscar, etc. It would have been

quite impossible for him to disgrace one of his “tall,

swift, venatic hounds” with so Saxon a name as Rover or

Barkis. But his enthusiasm is so genuine, and there is

such a wealth of curious information in his pages, that

his book has a charm and a substantial value of its own.

The other

work of Mr. Cupples was, like that of most of the

journalistic men of letters of the period, largely

anonymous. His essay on Emerson, contributed to the

Douglas Jerrold’s Magazine, is very highly spoken of.

Personally, Mr. Cupples must have been a man of great

simplicity and charm, a happy combination of the genuine

and most agreeable traits of that hearty and outspoken

variety of man, the literary Scotchman.

Kyloe

Jock and the Weird of Wanton-Walls

[serialised in MacMillan’s Magazine Volumes Two and Three in 1860]

Chapters 1 - 2

Chapters 3 - 4

Chapters 5 - 6

The Sunken Rock Mrs

George Cupples was born Ann Jane Dunn Douglas, on 4

January 1839 at 34 Gilmore Place, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Geneaolgy

A

monograph, written by her Grand niece, Elspeth White.

She was the third of the seven children of Archibald

Douglas of Morton and his wife, Caroline Montague Scott

Prentice, daughter of Captain Ebenezer Prentice of the

Scots’ Fusiliers. Archibald Douglas also came from a

military background but he had joined the Civil Service

and was destined for a post in New Zealand, when he died

suddenly at the age of fifty-five. His widow, who must

have been a woman of great strength and ability, decided

to proceed to New Zealand as planned. She arrived in

Dunedin in 1858 where she opened a small school near

Pelichet Bay.

Caroline Douglas took five daughters to Dunedin with

her, leaving in Edinburgh her only son who followed

later and her daughter, Ann Jane about whom this

monograph is written. At this time Ann Jane was nineteen

years of age and George Cupples was thirty-six and one

of the most respected literary figures of Edinburgh. He

was a noted contributor to Blackwood’s Magazine, an

essayist and author of novels, including The Green Hand,

a best-selling novel of the sea which went into five

editions between 1856 and 1908.

So it was to a literary lion that the nineteen-year-old

Ann Jane was married, and is it any wonder that her

first books to be published were simply under the

initials A.J.C.? Bearing in mind that it was customary

for women authors of Victorian times to use their

husband’s names, it is not surprising that she later

published as Mrs George Cupples; although there may have

been also an element of expediency in being able to make

use of such a prestigious name in the publishing world.

George Cupples was in his other capacity a famous

breeder of Scotch deer hounds, said by him to be ‘one of

the noblest races of quadrupeds ever known’ -and I

imagine, of the canine race, one of the most alarming.

After George Cupples died in 1891, his wife edited and

published his life’s findings on these dogs in a lavish

illustrated book of over three hundred pages called

Scotch Deer hounds and their Masters. And it was

obvious, from references in her stories to these dogs,

that she shared her husband’s love of this noble race of

quadrupeds.

Ivan Illich has said that children were a nineteenth

century invention. Before that they were regarded as

incipient adults. Women authors took up their pens in

droves to write for this delightful invention. Mrs

Cupples must have been one of the more prolific of these

women writers for children, for the British Library at

the British Museum holds forty-eight of her books. A

list of these with sub-titles, publishers and dates of

publication is attached. I would like to single out some

titles as they relate to the author’s life.

It would appear from the British Library list that Mrs

Cupples’ first book to be published was Unexpected

Pleasures or, Left Alone in the Holidays. Here she uses

the technique, popular at the time, of a secondary title

which gives the purchaser some idea of the trend of the

book - and the readers a hint of the message for them.

This book was published by W.P. Nimmo, Edinburgh in

1868. This date is interesting. It was exactly ten years

since the Cupples were married. Ann Jane was twenty-nine

years old and it may have been that she realised that

she was not going to have children and that she was

looking for a productive means of filling in her time by

writing for other people’s children.

The next year, 1869, saw the publication of her

full-length novel for boys, Norrie Seton or, Driven to

Sea, published by W. P. Nimmo, Edinburgh. This was a

good yarn and must have been popular, for Nimmos brought

out a very fine new edition in 1896.

In this book, as in all her sea stories, Mrs Cupples

must have drawn almost completely on her husband´s early

experiences at sea, so at this point it would be helpful

to consider the young George Cupples.

He was born in 1822, and his father was the minister of

Legerwood, a small parish just north of Melrose in the

Scottish county of Berwick. George’s first lessons were

from his father but, at the age of ten he went to

school, walking five miles each way in all weathers.

When he was twelve, his family moved to Stirling and,

reading between the lines of the discreetly-guarded

Memoir written by Dr James Hutchinson Stirling, it

becomes apparent that he got into some sort of trouble

with a rowdy element in the town. It seems that he was

so afraid of his father’s anger that he ran away to sea.

The Memoir is less guarded in its description of

George’s father: ‘.. a terrible father, and in his

Covenanting Calvinistic rigidity and strictness, a

perfectly awful man.’

A life on the ocean wave seemed to be the only escape

(and indeed, it was the traditional escape in those

days), but it proved to be even worse than life at home

with his father. Poor George could not take the crudity

and the terrible hardships of sailing-ship life, and

after eighteen months plying the trade route to India,

he came home in a state of ‘penitential cowedness’, as

his brother described his condition. He begged his

father to have his indentures cancelled, in other words

to buy him out of the service. This ‘the awful man’

fortunately did, and for the next eight years George

studied at Edinburgh University.

It would seem obvious that Mrs Cupples’ sea story Norrie

Seton; or, Driven to Sea, was certainly inspired by the

unfortunate circumstances of her husband’s teenage

years. In this book it is Major Seton, the over-strict

uncle, who drives the young hero to sea. Like George

Cupples, Norrie Seton had had a scrape with the local

police and, although not the guilty one, his refusal to

tell on his friends caused his uncle to chastise him

unmercifully.

Norrie runs away and joins the ship ‘Vulcan’, bound for

San Francisco. It is obvious from the beginning that

Norrie, unlike George Cupples, is going to make a

success of the venture. He put up with the injustices

imposed on him by a bullying second mate, never losing

his stoic calm. He sang sea-shanties admirably, so

winning a great following among the sailors. He sorted

out a dirty situation with some mutineers, saved people

who fell overboard, and ended his first voyage a

competent apprentice with a letter from his captain to

say so.

The circumstances of going to sea and the experiences

suffered at sea were similar in the cases of both the

author’s hero, Norrie Seton and her husband, George

Cupples. Their return home, however, could not have been

more different - Norrie Seton to the warm embrace of an

apologetic uncle and an admiring family circle; George

Cupples in a ‘state of abject cowedness’ to his terrible

father, to be bought out of the Service as a failure. It

was almost as if Mrs Cupples could not bear the

unkindness meted out to her husband and so decided to

write his story differently.

1869 was an important year for Mrs Cupples for not only

did she publish Norrie Seton, but in that year she was

discovered by the publishers T. Nelson & Sons, London.

During that year Nelsons published her books Alice

Leighton; or, A Good Name is rather to be chosen than

riches;, Carrys Rose; or, The Magic of Kindness; and

Hugh Wellwoods Sucess; or, Where Theres a Will Theres a

Way.

The partnership with Nelsons was to prove a happy one,

and in all they published twenty-six of her titles.

George Cupples must have encouraged his wife in this

profitable pursuit, and it is pleasant to picture the

husband and wife sitting by the fire checking

manuscripts with a deer-hound or two spread between them

on the hearth-rug.

The next year brought more sea stories from Mrs Cupples’

pen. Bill Marlin’s Tales of the Sea, Johnstone, Hunter &

Co, Edinburgh, although undated is given the date 1870

in the British Library catalogue. This book is

dedicated as follows:

To

My Two Little Sisters

In New Zealand

H. & J.

These Tales are

Affectionately Inscribed

Her two

little sisters were by that date nineteen and twenty-one

years respectively. ‘H’ was to become Mrs Helen Hutton

and ´J´, Mrs Janet Ramsay (my grandmother), both of whom

lived and died in Dunedin.

So it can only be assumed that Mrs Cupples wrote these

stories for the little sisters she missed so much and

sent them in manuscript form to New Zealand, leaving the

inscription intact when the books were finally published

in 1870.

Bill Marlin’s Tales contains two long stories and in

both of them Mrs Cupples uses one of her husband’s

literary devices. In his novel The Green Hand, George

Cupples tells his story through a ship’s captain

reminiscing with his passengers in the saloon after

dinner during a long voyage. Mrs Cupples, writing for

children, uses the same technique, but has Bill Marlin,

an old seaman, as the narrator telling stories to his

grandchildren by the fire before they go to bed. Indeed,

she uses this method often of an older person telling

the child a story.

The first of Bill Marlin’s stories, Miss Matty: or, Our

youngest passenger, tells of a very nice little girl

travelling to England from India after the death of her

mother. During he voyage, she manages to civilise the

rather wild crew of the good ship ´Mersey´, and to keep

their spirits up while they spent a miserable time

shipwrecked on an uninhabited island. Her optimism was

not misplaced - rescue was at hand.

The second story is interesting in that again, as in

Norrie Seton, Mrs Cupples uses her husband’s unfortunate

experiences. Like George Cupples, the hero of The Little

Captain, Midshipman Charles Harvey, was the son of a

clergyman and of a religious nature. Because he read his

Bible regularly, he was ridiculed unmercifully and

treated with both physical and mental cruelty by the

officer of his watch and his fellow apprentices. Again

we see Mrs Cupples’ determination to turn her husband’s

failure at sea into a success story. In this book, the

ordinary seamen recognise Charles Harvey’s worth, and to

them he is known as ‘the little captain’. When he goes

ashore at Mozambique to save some of his shipmates baled

up by the natives, he receives a fatal stab wound. His

death turns him into a classical hero.

The Little Captain was also brought out by Johnstone,

Hunter & Co under that title along with Gottfried of the

Iron Hand: a Tale of German Chivalry. This is a similar

edition to Bill Marlin’s Tales, and also has the

dedication to her little sisters in New Zealand but the

author styles herself ‘A.J.C.’, not Mrs George Cupples,

as in the companion volume. This makes one wonder if it

could be earlier.

The Little Captain must have been a very popular story

because it was published again in 1885, this time by

Gall & Inglis, London, Edinburgh. Lists show some five

more titles in second editions. Alf Jetsam, Blackie &

Sons, London, 1886, was brought out again by Blackies in

an abridged edition as late as 1933.

Animal stories came second to the sea as a favourite

subject for Mrs Cupples and, provided one can understand

the Scottish dialect she employed, one of her most

delightfully amusing books about animals is Tappy’s

Chicks, Strahan & Co, London, 1872. This book has the

sub-title, Links between Nature and Human Nature, and it

contains twelve stories about such diverse creatures as

ferrets, pigs, monkeys, ducklings and her beloved dogs -

the best and funniest is about The Laird’s Staghound.

In her writings her delight in animals is obvious. In

all Mrs Cupples’ books, that I have seen, both at the

Dorothy Neal White Collection at the National Library,

Wellington, and in my own collection, there is hardly a

story in which some particularly pleasant dog does not

appear.

I have said that many of her books were published by T.

Nelson & Sons. Most of these were instructive, and many

had the moral tag demanded so often by Victorian

publishers. The following titles show this trend: Bertha

Marchmont: or, All is Not Gold that Glitters; Bluff

Crag: or, A Good Word Costs Nothing; Carry’s Rose; or,

The Magic of Kindness.

But even Nelsons gave her her head and allowed her her

humour every now and then. In The Cockatoo’s Story, T.

Nelson & Sons, Paternoster Row, 1881, for instance, we

meet a wise old parrot who had been, by a twist of

irony, ‘the favourite Polly of an old bird-stuffer’ and

also a macaw, the Great Mogul, who had learned so many

bad words from his previous sailor owner that he had to

be segregated from the parrot for fear of moral

contamination.

In those days when government help for the poor was

minimal, Mrs Cupples gave a lot of her time to social

work for the underprivileged. She aroused a great deal

of public interest in the founding of a home for the

training of orphan girls and boys from Glasgow. This

home, erected by public subscription, was situated on

Duchray Water, Aberfoyle. She was also a member of the

committee of the Edinburgh YWCA.

However, her social work at Newhaven probably showed her

compassion most markedly. Newhaven is a fishing village

near Edinburgh and here the fishwives worked on the

wharf where the herring fleet came in, cleaning and

scaling the fish as the great baskets were brought out

of the boats. It was an appalling and filthy job for

these women, working in the bitter winds off the North

Sea, their hands chapped and bleeding from the constant

contact with the salt and the awful cold. Here Mrs

Cupples went to work among these women as a voluntary

social worker, organising what practical help she could

for them and giving then the support of her friendship.

The depth and sincerity of their love and gratitude was

shown when, some 15 years after Mrs Cupples left

Scotland for New Zealand, my mother (her niece) visited

Scotland and called at the wharf at Newhaven to see the

scene she had heard about from her aunt. The fishwives

were still there and when my mother told them that she

was the niece of Mrs Cupples, she was surrounded by

tearful women all wanting to embrace her. She ended up,

according to reports, covered in scales, smelling very

fishy, but inordinately proud of her aunt.

On 17 October 1891, George Cupples died aged 69 years,

and three years later Mrs Cupples decided to join her

sisters in New Zealand. She sailed from Plymouth in RMS

´Gothic´ for Port Chalmers, arriving there on 14

November 1894. She spent the next four years living with

her unmarried sisters, Margaret and Caroline Douglas who

lived at Mosgiel, near Dunedin.

Mrs Cupples died at Mosgiel on 19 November 1898, aged 59

years, and the only obituary notice was in the Taieri

Advocate of 23 November 1898, which read as follows:

‘… she was a lady of considerable literary ability, and

when in good health was a contributor to Home journals.

For a long time she conducted a ladies column in the

Taieri Advocate, her nom de plume being Penelope.’

It seemed sad that this energetic and talented writer

with a distinguished record of publications in England

and Scotland should only be known in New Zealand as a

contributor to ladies’ journals.

For that reason I was prompted to write this monograph,

and I hope it may prove useful to anyone who is

interested in the significant collection of the books of

Ann Jane Cupples in the Dorothy Neal White Collection.

Carry's Rose or, the Magic

of Kindness. A Tale for the Young

Mrs. George Cupples (1881) (Text File)

The Cockatoo's Story

Mrs. George Cupples (1881) (Text File)

Bluff Crag or, A Good Word Costs

Nothing

Mrs. George Cupples (1872) (Text File)

Singular Creatures and

How they were Found

Being Stories and Studies from the Zoology of a Scottish

Parish

Mrs. George Cupples (1872) (pdf File)

My Pretty Scrap-Book

Picture Pages and Pleasant Stories for

Little Readers

Mrs. George Cupples (1874) (pdf File)

Bibliography

A History of the Douglas Family of Morton (Dumfriesshire)

and their Descendants, Percy W.L. Adams. Privately

published. The Sydney Press: Bedford. 1921

Scotch Deer Hounds and their Masters. George Cupples,

with biographical sketch by James Hutchinson Stirling,

LLD, Wm Blackwood & Sons: Edinburgh & London. 1894

BOOKS BY MRS CUPPLES HELD IN THE DOROTHY NEAL WHITE ROOM

INTRODUCTION

Through the generosity of the descendants of Mrs Cupples’

brothers and sisters the Children’s Historical

Collection contains twenty-three of Mrs Cupples’ books.

We are extremely fortunate to have these books as they

are significant for a variety of reasons.

First of all, there is the New Zealand connection

explained in Elspeth White’s memoir. While none of these

books was written in New Zealand, Mrs Cupples kept in

close touch with her family and joined them for the last

four years of her life.

In addition, her writings are a valuable resource for

any student of Victorian children’s literature. Mrs

Cupples is an excellent example of the professional

woman writer of the period. Her writing style is an

accomplished one and she could turn her hand to whatever

the market required. Consequently her range of books

represents a microcosm of popular genres in children’s

writing of the mid-Victorian period. For older readers

she produced tales of nautical adventure and

Robinsonnades. Moral tales and natural history stories

were written for a variety of age‑groups.

Some of her best stories about animals make good use of

her intimate knowledge of Scottish working life. She

also produced a number of ‘picture page’ books for the

very young, writing stories, to fit illustrations

supplied by the publisher.

The topics and themes she chose are typical of what was

considered suitable for young readers in this period.

Within this framework her characters are often robust

and adventurous, and humour as well as piety can be

found.

Mrs Cupples was well‑served by her publishers who

ensured a good standard of illustration and binding for

her books. Their decorative and often pictorial covers

made them among the most attractive books of their era

in the collection. Displayed together they provide the

onlooker with an overview of many key features of

publishing for children in the 1870s.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The adventures of Mark Willis London : Nelson, 1872

168p. Coloured frontispiece. Engraved illustrations.

Inscribed ´To Mr Robert L Cupples with the authors

kindest regards 27th Nov 1873.

The adventures of Mark Willis London : Nelson, 1897

167p. Pictorial cover. Frontispiece missing

Bill Marlin’s tales of the sea. Edinburgh : Johnstone,

Hunter, 1870 Comprises two stories: Miss Matty: or, our

youngest passenger 145p. and The little captain: a tale

of ‑the sea, 96p. Carries the printed dedication ´To my

two little sisters in New Zealand H & J, these tales are

affectionately inscribed.´

A book about house work: a convenient manual for

mistresses and maids with useful hints and receipts in

the various departments of housekeeping. 3d ed.

Edinburgh: J. Menzies, 1878. 96p. Paperbound.

Edenside: the lights and shadows of our village

Edinburgh : The Religious Tract and Book Society of

Scotland, 1881. 163p. Engraved illustrations.

Helpful words from a barn door Edinburgh: John Maclaren,

1879. 19p. A threepenny religious tract.

The hidden talent: or, use in everything London: Nelson,

1875. 61p. Pictorial cover. Engraved illustrations.

Hugh Wellwood’s success: or, where there’s a will

there’s a way London Nelson, 1869. 48p. Engraved

illustrations.

Katty Lester: a book for girls London : Marcus Ward,

1873. 118p. The chromographs are facsimiles of the

original drawings made for Vere Foster, Esq., by

Harrison Weir.

The lost rabbit: or, look at everything and touch

nothing. London: Nelson, 1875. 61p. Engraved

illustrations.

Mamma’s stories about domestic pets London: Nelson,

1876. 168p. Pictorial cover, red binding. Engraved

illustrations.

Mamma’s stories about domestic pets. London : Nelson,

1876. 168p. Pictorial cover, green binding. Engraved

illustrations. This copy is sub‑titled about wild

animals on cover, perhaps through a bindery confusion

with Talks with Uncle Richard about wild animals issued

in identical binding the same year.

My pretty scrap‑book: or, picture pages and pleasing

stories for little readers. London: Nelson, 1883. 92p.

Pictorial cover. ´With eighty‑two illustrations´.

Includes on p.79 ´A New Zealand chief´

Norrie Seton: or driven to sea Edinburgh: William P

Nimmo, 1869. 422p. Engraved illustrations. Publishers

catalogue for 1871 appended.

Our parlour Panorama London: Nelson, 1882. 92p.

Pictorial cover. “With eighty‑two illustrations”.

Singular creatures and how they were found: being

stories and studies from a domestic zoology of a Scotch

Parish Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1872. 333p. US edition

of Tappy’s chicks. Inscribed ´To the author Mrs George

Cupples with the affectionate regards of her nephew J.G.

Cupples Boston, Mass. USA May 23/78´.

Talks with Uncle Richard about wild animals London:

Nelson, 1876 167p. Pictorial cover Engraved

illustrations.

Tappy’s chicks: Sep/75 and other links between nature

and human nature London Strahan, 1872 321p. ´With

nineteen illustrations´. Inscribed ´To my beloved mother

from her affectionate daughter The Author, 2nd April

1872´

Terrapin Island: or adventures with the ´Gleam´

Edinburgh: Gall & Inglis, 1876 288p. ´Eight woodcuts´

Tim Leeson’s first shilling: or, try again London:

Nelson, 1875. 64p. Engraved illustrations.

Walks and talks with Grandpa London: Nelson, 1876. 120p.

Pictorial cover. Engraved illustrations.

Young bright‑eye: or, Charlie Harvey’s first voyage

Edinburgh: Gall & Inglis, 1875. 224p. ´Four full‑page

cuts´. 2 copies. One is inscribed ´To Archie D Burns

from his aunt wishing him many happy returns of his

birthday 29th Sep/75´

Also held in the Dorothy Neal White Room are three books

by Mr George Cupples, the authors husband: Sep/75

Cupples Howe, mariner: a tale of the sea Boston: Cupples,

Upham, 1885. 258p.

The green hand: adventures of a naval lieutenant: a sea

story for boys London: Routledge, 1879. 448p. Engraved

illustrations. Preface dated 1878 states this is a

´revised edition, freed from various expressions now to

a certain extent obsolete or otherwise unsuitable, so as

to make it more thoroughly fit for juvenile readers´

Sep/75

The two frigates London: Routledge, 1859. 387p. This

edition issued as part of 'Routledge’s Railway Library´

|